an exploration of monsters in British literature and beyond

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Video

youtube

Dear students,

Our first major text in the course is the Old English poem Beowulf. The name of the author or authors remains unknown to us, but it is generally agreed that she, he, or they were members of the cultural group we now call the Anglo-Saxons.

Please watch this short video about the Anglo-Saxons. In your daybook, mark out the work area for a standard blank opening (as previously described). Then do the following:

On the left-hand page, make a list summarizing the top ten facts in the video.

On the right-hand page, do the following 3-2-1 exercise:

Write which three facts you think (i.e. in your opinion) might have the greatest impact on our ability to understand literature composed by the Anglo-Saxons and why you think those factors are important.

Write which two facts you found the most intriguing, facts you would like to know more about.

Finally, write one question you are left with after watching this video.

Peace & love,

Professor Gigan

PS: If you run out of space in your work are on the right-hand page, turn the page, mark out a new work area on the next page and work there. Please do not write outside your pre-marked work area.

0 notes

Photo

Today I’d like you to open up your daybook to any blank opening (2 page spread), mark out your work areas (as described in a previous post) and write about your early history as a reader and user of language. Here are some questions to consider, though you don’t have answer all (or any) of them:

Questions about Your Reading Life Before You Started School

Did your parents or someone else read to you or tell you bedtime stories? Did you like it? What kinds of books did they read to you? Picture books? Did you have favorites? What were they?

Were there favorite anecdotes that were often told at family gatherings.

Were there books and magazines in your house? Who read them? Did you see your parents reading?

Did you play with alphabet blocks?

Did you go to nursery school, a Head Start program, or a local library where stories were read aloud to you? Who read them? Did you like the stories? Did you like the reader?

Did you watch the reading segments on educational television shows like Sesame Street? Did you enjoy them? Did you pay attention and follow the instructions?

What other kinds of shows did you watch? Did you watch the commercials? Which do you still remember? Do you remember any of the jingles?

Did you listen to stories on the radio? What were they about?

Did anyone make an active, conscious effort to teach you to read? Did anyone help you read when you asked for help? If so, who? If you asked what a sign meant, did you get a positive reaction?

Were you taken to the library and shown how to check out books?

Were you given books as presents or rewards?

Were you encouraged to talk? Did your parents listen to you? Did they look at you when you talked to them? In your family, did one speaker often interrupt another?

Were you able to read before you started school? What kinds of things did you read, and how well?

These questions are based upon a list from Ron Padgett’s delightful book Creative Reading: What It Is, How to Do It, and Why. Padgett’s work was first published in 1997, a time when were are all always completely engulfed in the digital world. That’s why there are no questions about the internet or educational software. Please don’t hesitate to talk about those things if they are relevant to your early history as a linguistic being.

Additionally, Padgett doesn’t consider the role of the linguistic variety in our early lives. If English wasn’t spoken in your home or was in competition with another language, that might be something you’d like to write about. It certainly affected your development as a human using language in the world.

Love,

Professor Gigan

0 notes

Photo

The daybook is a space where you explore our course content every day. Remember, you should fill up that daybook before we reach the end of the semester! The exercise below represents the default activity for your daybook. That is to say, if you have no other instructions or ideas for a given day, do this:

Transcribe & React

Begin with a blank opening (2 page spread).

Mark out the margins of your work area. For 4 squares per inch ruled paper the inside margin is 4 squares, the top margin is 5 squares, the outside margin is 6 squares, and the bottom margin is 7 squares. For 5 squares per inch use inside 5, top 6, outside 8, bottom 10.

Find a passage in our current text (or one of the other course texts, if you’d rather). You should pick a favorite passage,an interesting one, or one you are struggling with. Or just open the text up to a random spot.

On the left-hand page, on the first line of your work area, write the name of the text and where you are starting. Something like “Beowulf, starting at line 273″ or “Frankenstein, beginning with the second sentence on page 135.”

Transcribe (that is, copy by hand) as much of the text as will fit in the work area you have marked out.

On the opposite page, you will use the work area to react to the passage that you have transcribed. This can take many forms. The following are examples you can pick from. Perhaps you will come up with better ways to react as you get a feel for this exercise. Until then, pick one of these:

Using a different color of ink than you started with, go back to the left-hand page and underline any words you don’t know. Look those words up and put definitions in the right-hand work area, like you are making a tiny glossary.

Rewrite the passage in your own words. Try to preserve as much of the meaning as possible, while changing the text into “plain English.”

Draw a sketch, illustration, map, diagram, or chart that helps make the passage clearer.

Write what would come after the passage, if you were the original author.

Find another text (one from the course, a book you like, lyrics from a favorite song, whatever) that you can transcribe on the right-hand page that seems to be in conversation with the first text in some way.

If you have some strong emotional reaction to the passage (hate, love, envy, etc.), write about it. Try to describe your feelings as accurately as possible. Talk about why you think you feel this way.

Hit up wikipedia or some other source for historical information that might throw light on the text. Write down some useful facts.

If you find the text baffling, use the right-hand page to build a list of specific questions you need answered to understand the passage. This would be a great thing to mention in class or bring to office hours, but you don’t have to do either of those things.

This is a daybook exercise, not an exam question, so try not to worry about whether you’re doing it right or not. If the result of this work is that you are thinking about the text in new ways, then you are doing it right!

Peace,

Professor Gigan

0 notes

Photo

The Rights of the Reader is a 2006 English translation of a French book by educator Daniel Pennac. In it, Pennac identifies 10 Rights. In a blank opening (2-page spread), copy these Rights down on the lefthand page. Fill the page with this list, your own personal declaration of your rights as a reader:

The Rights of the Reader

The Right Not to Read

The Right to Skip

The Right Not to Finish a Book

The Right to Read It Again

The Right to Read Anything

The Right to Mistake a Book for Real Life

The Right to Read Anywhere

The Right to Dip In

The Right to Read Out Loud

The Right to Be Quiet

Think about these rights for a bit. What do they mean? What are their implications for you? For your career as a student? On the right hand page write a paragraph or two exploring what it means to take up these rights.

Peace & Love,

Professor Gigan

0 notes

Photo

Greetings, students! It is I, Professor Gigan! In this course we will not simply study monsters, we will become monsters as well! One of the reasons many people like to dress up as monsters for Halloween is so they can act a little silly or mischievous while hiding behind the anonymity of a mask. We are all going to adopt monster personas for much the same reason. Here are just some examples of the kind of monster you could be:

A classic Halloween monster like a vampire, mummy, ghost, etc.

A famous monster from film, TV, comic books, literature, etc.: Dracula, Blacula, Godzilla, etc.

A Scooby-Doo badguy

A fairy folk: elf, sprite, pixie, mermaid, goblin, etc.

A creature from mythology: hydra, troll, bunyip, etc.

A monster from a video game or Dungeons & Dragons

Your favorite Pokemon

A monster you invent yourself, like Bugface, a monster I just made up who is a guy with a big wiggly bug where his face should be.

A dinosaur or other prehistoric beast

Do not name yourself Psycho Killer or after one of the famous psycho killers of fiction or history. Psycho Killer as a category of monster tends to do real harm to our perceptions of the mentally ill. Just don’t go there, please.

We are going to be polite and formal monsters, so every monster name needs an honorific, like Mr. Bugface or Ms. Mermaid. In addition to Mr., Miss, Ms., and Mrs., you could use Mx., pronounced ‘miks,’ as a gender-neutral option.

Please don’t use a professional honorific (like Doctor or Lieutenant) unless you are actually entitled to that rank. However, feel free to call yourself by some ridiculous noble title like Princess Goblin or Duke Pikachu if that sort of thing suits you.

Once you have an idea for your monster person, open your daybook to the next blank two-page spread (or “opening”). On the left side label the page “Monster Persona: Mx. Cyclops” or whatever is appropriate. Then write a few sentences explaining why you picked that monster. Who is this monster to you? What do they signify? How does this monster matter to you? If the creature is obscure, consider offering a brief explanation.

On the opposite page, make a full-page picture of your selected monster. You do not have to be a good artist to do this! After all, this isn’t an art class. Amateurish scribbling is perfectly fine. If you can’t quite bring yourself to try a drawing, you could print out a picture and paste it to the page.

Finally, you need to let me know about your monster persona. We’ll use the Assignments tool in ReggieNet for that. In there, you should find an assignment labeled “Monster Persona.” All you have to do to complete the assignment is type in your honorific and monster name in the dialogue box, then hit “submit.” That’s it! Note that in the event two people request similar monster personas, I will ask one of you to pick something else. Dibs will go to the monster who submitted their persona first.

I can’t wait to meet your monster personas!

Love,

Professor Gigan

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Roy Lichtenstein, Compositions

Greetings, fellow investigators of literature!

The daybook is the primary investigative tool for this course. A required material for this course is a composition notebook, similar to the one pictured above in Lichtenstein’s painting. It must be at least 9 3/4 inches and 7 1/2 inches wide, consisting of no fewer than 80 sheets (160 pages). It should be quad ruled. That is, the insides should be graph paper, preferably four or five squares to an inch.

Note that a spiral bound notebook or other form of non-composition book is not an acceptable starting point for a daybook. You need a proper composition notebook with sturdy pages sewn into the spine. You’ll also need some writing utensils, such as pens and pencils, Some assignments will specifically ask you to write in more than one color. You may also want to acquire some markers, colored pencils, and/or crayons for use with your daybook.

Additionally, you’ll also need a gluestick or pot of rubber cement (I recommend the latter) for when we paste things into our daybooks. And you’ll want a few dollars for photocopies (placed on your Redbird Card if you want to use ISU copiers). Five bucks ought to do it, unless you end up making a lot of stuff in full color.

All these items, along with the selected works of literature, constitute the basic required materials of the course. With the exception of adding money to your Redbird Card for photocopies, all of these materials should be obtainable on campus at either the Barnes & Noble in the Bone Student Center, the Alamo bookstore next to Stevenson Hall, or the CVS pharmacy in Uptown Normal.

Once you have acquired your daybook, open it up to the first page and fill the page with a message like this:

IF FOUND PLEASE RETURN TO [YOUR NAME] [YOUR EMAIL ADDRESS] Thank you in advance!

Your daybook’s pages can and should hold anything you want: shopping lists, diary entries, doodles, notes for other classes, etc. Start writing whatever you want in it right away! Much of your homework in Eng110 will consist of reading, thinking, learning, and then documenting that learning by writing in your daybook. It is called a daybook because your task is to add material to it every day. You should always bring your daybook to class, as we will often write in them or compare what we have written between class meetings. And you should generally have it with you wherever you go.

Your daybook should be your constant companion this semester.

0 notes

Quote

I hope to add something to our understanding of what it meant to be a human animal in the nineteenth century. What I can’t do is say anything systematising about the ‘Victorian body.’ At best, these case histories are panes of glass through which to catch a partial glimpse of a huge, teeming landscape of thought and feeling that may, in fact, never become fully comprehensible to us. That’s because the body, no matter how we might like to imagine it as a safe haven from the messy contingency if history, is deeply implicated in it. Put simply, a broken wrist in 1866 does not mean, and may not even feel, the same as it would today. It’s not just a question of whether the Victorians had codeine and splints to make things better, but the far less easily settled matter of how they regarded their wrists - as part of their essential core, or as a peripheral wing? And then, what about the middle aged woman who in 1857, sends a letter congratulating her niece on looking so ‘fat’? We gasp at Aunty’s insult, and it takes a while to realise that what is being offered is actually a loving, relieved compliment, a celebration of blooming good health in an age where slenderness is death’s calling card. If only we come prepared to check our impulse to map our own bodily experiences directly on to the nineteenth century will we begin to understand what is really going on.

Victorians Undone: Tales of the Flesh in the Age of Decorum // Kathryn Hughes

12 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Sometimes, in our confusion, we have been known to turn the Other into a monster and a god. Hierophanies – where the unshowable deity shows itself – are often terrifying. Hence the double etymology of monstrare, to show and to warn. Zeus’ mutations into a plundering bull or rapacious swan epitomize this paradox. And Kali certainly knew how to scare mortals. Even the generally ‘good’ biblical God could resort to horror on occasion, as Job realized; or Abraham when commanded to kill Isaac, or Jacob when he found himself maimed at the hip after wrestling with the dark angel of Israel. Or Zechariah struck dumb by the angel Gabriel. Not to mention the tales of floods and plagues and conflagrations sent by a jealous God to fill his people with fear. Divine monstrance was not infrequently an occasion of terror. Fascinans et tremendum, as the mystics said.Poets too have attested to this enigma of the monstrous God. W.B. Yeats captured this disturbing ambiguity of the sacred, for example, in his apocalyptic image of the ‘rough beast slouching towards Bethlehem to be born’. A sentiment echoed by Rilke in his famous opening apostrophe to the Duino Elegies: ‘Every angel is terrible’. And one might also recall here Herman Melville’s chilling evocation of the quasi-divine, quasi-demonic whiteness of the whale, recalling at once the horror of Leviathan and the transcendence of Yahweh.

Richard Kearney (Strangers, Gods and Monsters: Interpreting Otherness)

2K notes

·

View notes

Quote

My cousin Helen, who is in her 90s now, was in the Warsaw ghetto during World War II. She and a bunch of the girls in the ghetto had to do sewing each day. And if you were found with a book, it was an automatic death penalty. She had gotten hold of a copy of ‘Gone With the Wind’, and she would take three or four hours out of her sleeping time each night to read. And then, during the hour or so when they were sewing the next day, she would tell them all the story. These girls were risking certain death for a story. And when she told me that story herself, it actually made what I do feel more important. Because giving people stories is not a luxury. It’s actually one of the things that you live and die for.

Neil Gaiman (via oiseauperdu)

89K notes

·

View notes

Photo

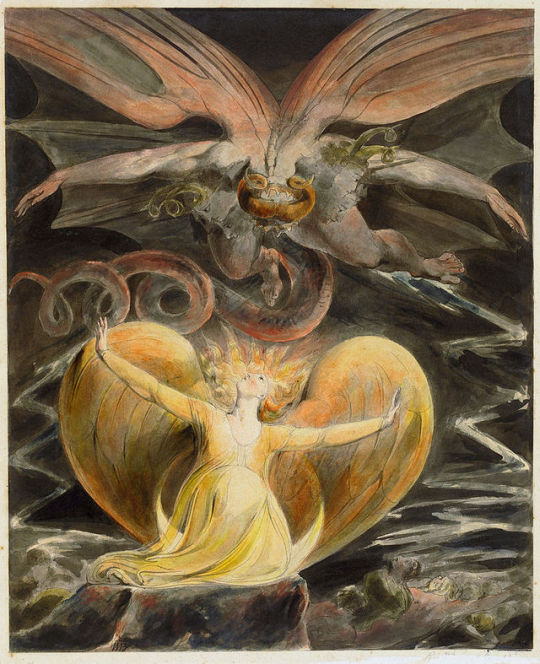

William Blake, Great Red Dragon paintings: The Great Red Dragon and the Beast from the Sea, The Great Red Dragon and the Woman Clothed With the Sun, The Number of the Beast is 666 and The Great Red Dragon and the Woman Clothed in Sun, 1805-1810

1K notes

·

View notes

Quote

Fairy tales, then, are not responsible for producing in children fear, or any of the shapes of fear; fairy tales do not give the child the idea of the evil or the ugly; that is in the child already, because it is in the world already. Fairy tales do not give the child his first idea of bogey. What fairy tales give the child is his first clear idea of the possible defeat of bogey. The baby has known the dragon intimately ever since he had an imagination. What the fairy tale provides for him is a St. George to kill the dragon.

G. K. Chesterton, Tremendous Trifles (1909), XVII: "The Red Angel"

0 notes

Quote

He who fights with monsters should look to it that he himself does not become a monster. And if you gaze long into an abyss, the abyss also gazes into you.

Friedrich Nietzsche, Beyond Good and Evil, Aphorism 146

0 notes

Text

Psalm 74:12-14

Authorized (King James) Version (AKJV)

12 For God is my King of old, working salvation in the midst of the earth. 13 Thou didst divide the sea by thy strength: thou brakest the heads of the dragons in the waters. 14 Thou brakest the heads of leviathan in pieces, and gavest him to be meat to the people inhabiting the wilderness.

Psalm 74 preserves an ancient memory of the God of the Old Testament (called Elohim in the original text) aids humanity by fighting dragons and the great multi-headed monster Leviathan. God then distributes the meat of the Leviathan as a boon to humanity.

0 notes

Quote

What would an ocean be without a monster lurking in the dark? It would be like sleep without dreams.

Werner Herzog (via diaphanee)

334 notes

·

View notes