Text

Further Reading - ‘Mass Consumption and Personal Identity’ by Peter K. Lunt and Sonia M. Livingstone

As part of my further reading, I have read ‘Mass Consumption and Personal Identity’ by Peter K. Lunt and Sonia M. Livingstone. The book explores everyday mass consumption, economic practices and personal and social identity. The book is a detailed account on rising consumerism and emerging capitalism, on money and how, and why, we spend it.

The book begins by introducing theories and experiences of everyday consumption. Drawing on arguments from theorist such as Marx and Simmel, Lunt and Livingstone discuss capitalism and the economic order and how this has impact societal values and personal identity. Money, and by association consumer goods, have become the pinnacle of successful, of status, of importance. We place our value into our material possessions and our economic placement. ‘Marx had argued that the value of a commodity is not an inherent property of things, but the result of evaluations made about them by people. Simmel argued that we attribute value to objects which we desire, and which resist our attainting them. Desire of goods and their associated valuation thus involves a separation of objects from people. In modern society, this separation can only be overcome by purchasing goods. Buying goods mean involvement in the exchange system and the consequent scarifies we have to make in terms in terms of labour and money to obtain goods.’ (Lunt, Livingstone, 1992 pg. 8). Essentially, in a capitalist society, our involvement in the economic and exchange system is most valued. Thus, our material possessions, and by association what we had to do to acquire them, impacts our social status and subsequent social value. The first chapter also discusses capitalism in relation to globalisation. ‘Capitalism has developed into a global economic system that seems to have gobbled up all local cultures in the creation of world markets’ (Lunt, Livingstone, 1992, p.10). With the evolution of global trade, we are less reliant of communities and tend to lose cultural ties.

Primarily, the beginning focuses on consumption regarding personal identity. ‘Capitalism has constructed the individual by first undermining traditional cultural forms and then offering the diverse consumption of mass culture. On this view, individual identity is an artefact of ideological processes which mystify the true economic processes of domination. The individual is distracted from the realities of their domination in the class system by the illusory freedom of personal choice. Marx was concerned with consumption only in so far as he saw the desire for goods as a fetish which clouds political consciousness by introducing false choices and concerns and by mystifying actual processes of exploitation. In this, he influenced the critical theory of the Frankfurt school, which regarded popular culture as vacuous, not affording possibilities of real intellectual thinking and as the site of the manipulation of the working classes by the capital. Thus, until recently, the expansion of popular culture was seen as a process through which the capital produced the false identity of individualism in order to manipulate the masses.’ (Lunt, Livingstone, 1992, p.10). Are we being manipulated and exploited by capitalism? Is any sense of individuality and personal freedom, especially regarding consumption, merely an illusion? Are we just puppets to capitalism and the economic system? Considering modern advertising and marketing, it is plausible that our consumer choices are not entirely our own. Advertising and marketing are inherently manipulative – their function is solely to make people consume. Popular culture also negates any form of individuality: it encourages mass consumption and relies on trends and popularity. It manipulates the masses in to consuming objects even if they don’t align with individual identity. In fact, popular culture, and subsequently mass consumption, is more about social status and representation than individual identity. Essentially, popular culture creates and encourages mass identity whilst it simultaneously discourages individuality and intellectual thinking. This poses the question - is consumerism a tool for social control? Does it eradicate individuality?

‘The material conditions of consumer society constitute the context within which people work out their identities. People’s involvement with material culture is such that mass consumption infiltrates everyday life not only at the levels of economic processes, social activities and household structures, but also at the level of meaningful psychological experience – affecting the construction of identities, the formation of relationships, the framing of events...for modern consumer cultures creates the need to have, to discover, an identity.’ (Lunt, Livingstone, 1992, p.24). Essentially, material possessions and consumer items have become synonymous with identity. It is through our possessions that we construct an identity and present it to the world. Ultimately our things become an extension of ourselves. Whilst it is understandable to buy in relation to your morals and values, this ideology creates a multitude of problems. It places excessive, and quite frankly unnecessary, importance on material possessions. It fosters and promotes materialism. Isn’t this ideology, at the root, shallow, greedy and capitalistic? It pressures us to consume and acquire. To foster an identity solely through objects. It also pressures us to buy purely representationally – we buy to present an identity, not necessary our own, and not for function or purpose. With the sheer volume of consumer goods readily available and the influence of trends and popular culture, which are forever changing, identity crises may be more common. Has it become more difficult, near say impossible, to formulate an (authentic) identity?

It also reinforces class systems and divides. Value is placed upon material possessions, therefore those with more money, and subsequently more possessions, hold the highest value in society. The third chapter ‘Saving and Borrowing’ looks specifically at finances, especially in relation to consumption. It discusses various topics such as debt, credit and savings which relate strongly to social class. Whilst the chapter does look at class, it is not a detailed account. Class has a huge impact on debt and the use of credit; the chapter could have elaborated more on this, evaluating and analysing society and class systems. It is naïve to (semi) ignore how social class may impact your financial situation and inclinations/beliefs. Those from lower- and working-class backgrounds may have to use and rely on credit. However, it is important to consider credit and how it maintains class systems and divides. Credit preys of the (financially) vulnerable; interest accumulates and results in more debt. It is a vicious cycle which many people, especially from the lower classes, find themselves in. There is also a stigma surrounding credit. Many, as discussed in the book, see it as bad and immoral and this only furthers the demonisation and judgement of the lower and working classes.

The next chapter, ‘The Meaning of Possessions’, looks more in depth that the relationship between identity and material objects. ‘The goods people possess affect their social reputation, their image of themselves and their self-esteem, their desire for future purchases, and their assessments of their relative standard of living and status in relation to others’ (Lunt, Livingstone, 1992, p. 59). This chapter reiterates the relationship between material possessions and self-image and identity. ‘In relation to others’ is key here. Our possessions have become a measurement of success and status. Of identifying ourselves in relation to others. Ultimately, they show us where we belong within society. Where our place is within the social hierarchy. This ties closely with self-esteem, as within modern society, we seek out validation from others. The chapter discusses the accumulation of material items as a ‘social comparison, emulation and competition process’ (Lunt, Livingstone, 1992, p.60) Like aforementioned, we use material possessions to determine our social, which leads consumerism to become a competition. A contest in which whoever owns the most, wins. This is inherently capitalistic – it shows how we are seen primarily as competitors and consumers. It discusses emulation - how trends and popular culture affect our consumer choices. We begin to emulate what we see. What we view are desirable. What we view as successful. Nowadays, through material objects, we can emulate any identity. The chapter also explores technological and economic advancement. ‘As norms of affluence and possessions change, so do social definitions of poverty and wealth’ (Lunt, Livingstone, 1992, pg. 62) Considering current rapid technological advancement, and well as changes within the economy, it is crucial to think how change can affect consumerism and our relationship with, and view of, material possessions. It completely redefines what is a luxury and what is a necessity. What is common place and what is a sign of status and affluence.

Moving forward, the book discusses modern ideologies of shopping and consumerism. Consumerism is now at the forefront of society - ‘shopping is no longer just the mundane act of going out and buying a product, retailing has become imbued with a whole new ethos, a new significance, a new cultural meaning – and commodities themselves seem to have taken on a new central role in people’s lives (Gardner and Sheppard, 1989. P.43). Lunt and Livingstone explore shopping habits and consumer identity in relation to modern society. They categorize shopping types and examine the reasoning behind our purchases. Do we indulge in leisurely shopping and retail therapy? Are we seduced by advertising and branding? Do we ignore the status-quo and buy rationally? Essentially, they ask how our views impact our shopping habits. ‘The person comes to the shop with acquisitive desire tempered by notions of personal control and the economy and the market aims to persuade, to seduce the person to become involved in the world of buying’ (Lunt, Livingstone, 1992, p.86). Whilst we may have preconceived views and ethics regarding consumption, companies now try to undermine this. They attempt, rather successfully, to manipulate and persuade us to buy. This is done through a variety of tactics – sales, marketing, branding, advertising, entire industries dedicated to making us consume. Lunt and Livingstone also consider the politics of shopping. Consumer boycotts and selective buying are just some ways in which shopping has become political activism. Not only can we forge an identity via material possessions and consumer purchases, we can also forge a political identity – create political ties and stances. It has, however, been argued whether we have any power as consumers. ‘although consumers can choose among a greater variety of goods, exercising more choice in mass consumption, and gaining a sense of identity through consumption, critics argue that such choices reflect no real freedom or power’ (Lunt, Livingstone, 1992, p. 100). Is freedom simply an illusion? Could it be that the idea of choice is merely a mirage? How much choice, do we as consumers, have? Marketing and advertising are inescapable in modern society – it is near impossible for them to have zero impact on your consumer choices. Additionally, there is also popular culture, the media, social media etc. All of which have an impact.

Lunt and Livingstone also consider the influences on economic and consumer beliefs. They discuss how a variety of sociological factors can affect our financial inclinations. In the chapter ‘Generational and Life Course Influences on Economic Beliefs’ (Lunt, Livingstone, 1992, p.102/103), they propose the significant social changes within modern society -

‘Consumer changes: greater range of consumer goods available (fueled by a technological revolution in processes of mass production); reduced durability of goods, in terms of both serviceability and desirability, replaced by increased expectation of having the newest and most fashionable version of the same product.

Marketing changes: explosion in the mass communication technologies which advertise, propagandize and persuade us to buy – in terms of exposure, targeting, expense and technique; development of shopping centres and malls at the expense of town centre and local shops.

Economic changes: increased availability of financial services for credit, changes in the forms of credit available, more flexible mortgage lending, debt facilities, and investment schemes; increased complexity and diversity of finances.

Social changes: introduction of the welfare state, increased home ownership, improved pension plans, increased leisure time, escalating divorce, cheaper travel, available contraception, more liberal sexual attitudes, more female employment and gender equality, greater importance of childhood and more defined consumer/fashion subgroups, increasing elderly population, and so forth.

When examining economic beliefs and consumer identities, it is crucial to analyse societal impact Afterall, we reflect, and are deeply influenced by, our society. They (Lunt and Livingstone) specifically look at generational differences regarding consumerism. They state, ‘generational representations become part of people’s constructions of their own identity’ (1992, p. 104). There have been substantial and rapid social and economic changes within the last few decades, hence such conflicting views between older and younger generations.

The book is an overall exploration and examination of consumer cultures and economics; it doesn’t give a definitive answer per se. In fact, it generates more questions than answers, questions about what influences our consumer choices and beliefs; what power we have as consumers. Etc. Essentially, this is an extremely thought-provoking text. Lunt and Livingstone are mostly thorough in their analysis; however, this isn’t entirely consistent throughout and some subjects are sort of glazed over and rather two-dimensional. They could have discussed a variety of social factors in more detail, for example class systems and divides. The book is also semi outdated now. When discussing technological advancements, family relations and gender roles, it is painfully clear it was written decades ago. Of course, this cannot be helped, and the majority of the book still upholds to modern society.

Bibliography -

Lunt, Peter K. and Livingstone, Sonia M. Mass Consumption and Personal Identity, Open University Press, 1992.

0 notes

Text

Vivienne Westwood

Vivienne Westwood is an esteemed fashion designer praised for incorporating protest, new wave and punk within mainstream fashion. Many of her designs are inherently political, often tackling social and environmental issues. She is also very forthright and outspoken politically, engaging with a variety of protests and campaigns. Westwood has forged a brand, or identity if you will, around antiauthoritarianism, rebellion and political activism. Considering this, her fashion designs essentially exist themselves as a form of protest art.

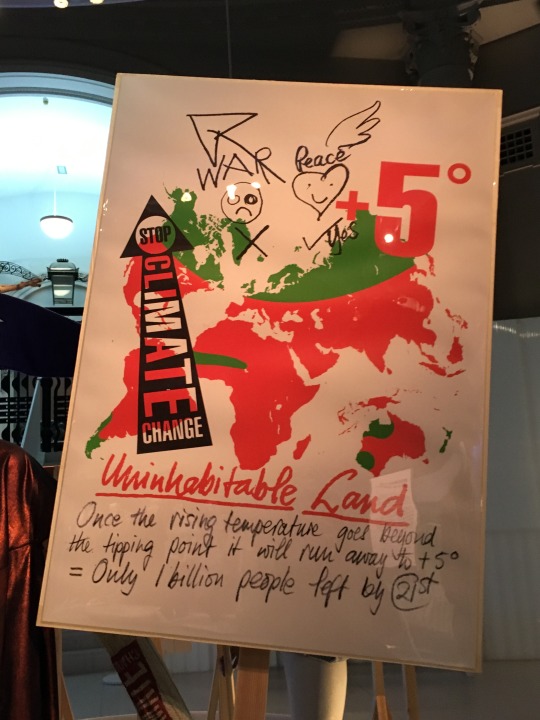

Vivienne Westwood has approached various issues; to note, she has campaigned for nuclear disarmament, civil rights, and both the green and labour parties. However, her most pronounced activism focuses on issues of environmentalism, climate change and consumerism. Within recent years, climate change and other ecological issues have been at the forefront of her brand and designs, with a strong focus on sustainability. She has worked with many organisations such as Greenpeace and PETA, attempting to educate and bring environmentalism and ecology to mainstream fashion.

Her core beliefs include: buying quality over quantity, using ethical and sustainable practices and materials and refraining from mindless consumerism. The popularized quote ‘buy less, choose well, make it last’ (Westwood, BBC) perfectly encapsulates her philosophy. Westwood has created the climate revolution – a website that hosts a variety of articles and other media by Westwood herself regarding her work on ecology and environmentalism, the active resistance to propaganda manifesto – a manifesto detailing the responsibility artists have regarding environmental issues, and a variety of fashion design pieces that highlight a variety of environmental issues, namely global warming and climate change.

On her website, Westwood details her approach to eco-friendly fashion. It is as follows:

‘September 2018

We want to become a model company for the future

Our core principles are:

1. QUALITY VS. QUANTITY

2. BUY LESS, CHOOSE WELL, MAKE IT LAST

3. REDUCE, REUSE, RECYCLE

ACTIVISM

Vivienne Westwood uses her collections and catwalk shows as a platform to campaign for positive activism. For many years she has been a mobilizing force in raising awareness about the negative effects of climate change and overconsumption, as well as the importance of art & culture.

FASHION: A FORCE FOR CHANGE

Vivienne Westwood – Fashion Designer & Activist

Co-operation with NGOs and industry organisations are fundamental to us.

COMMUNITY

We are a longtime champion of craftsmanship and heritage. We are proud to

work with local industries, artisans and small independent businesses.

PEOPLE

We strive to be a responsible employer and continually work to ensure equal opportunities for all employees, attracting, retaining and promoting talent, while celebrating ethnic, age, sexual and gender diversity, sexual orientation and gender identity.

We create a culture based on our values where every employee engages with the world through culture, art and education.

We motivate our staff and volunteers to protect the environment through sustainable practice.

Within our supply chain we check that the individuals & businesses we deal with provide desirable jobs, foster people’s skills, strengthen worker’s voices and lend support for vulnerable groups.

Everybody in our supply chain should be treated with respect and dignity and should earn a fair wage.

GAIA

We are working towards a Global Environmental Policy to monitor, control and review environmental impacts and drive continuous improvements.

We encourage our suppliers to be aware, concede to and implement their environmental responsibilities according to our Global Environmental Policy.

We are finalising a waste policy and our recycling scheme for all our premises.

We use 100% renewable energy sources in our premises where possible and are conducting a „Switch to Green Energy“campaign together with the British Fashion Council.

Sourcing our materials and services from sustainable or renewable origins is one of our main goals.

By focusing on environmental friendly dying and tanning techniques, we are reducing the amount of chemicals used in our production.

We will implement a Transport Policy to minimise our carbon footprint.

The transit packaging used for our products will be reduced and made more environmental friendly. All of our retail packaging is made of eco-friendly, plastic-free materials.

MATERIALS/ PRODUCTION

We have reduced the size of all our collections and therefore lessen our environmental impact.

We use recycling, upcycling, low waste and no waste experimental pattern cutting as design principles.

We are aiming to work only with partners who share our ethical values and have signed our Code of Labour Practice and Animal Sourcing Principles.’ (Vivienne Westwood/Our Approach, 2018)

In terms of design, Westwood has created a variety of products, ranging from t-shirts to handbags, surrounding many ecological issues. As well as (supposedly) adopting ethical practices and materials in all her ranges. Some particularly poignant examples of eco activism within her design include her ‘Save the Arctic’ and ‘Save the Rainforest’ t-shirt, both of which were played an active role within campaigns. The t-shirts adopt characteristics from typical political protest art, with the design mirroring that of a campaign poster. For example, they use block colours, slogans and symbols, all common iconography of protest art. This is an extremely effective design as it allows people to become an active part of the campaign, as it results in the public essentially advertising the campaign and its message. It also allows people to identity with Vivienne Westwood and her brand values – do they too identity as antiestablishment? Non-conformist? A punk? A rebel? A rule-breaker? Another note-worthy line was ‘Ethical Fashion Africa’ - a collection of handmade handbags of recycled materials. The project was based in Kenya, providing work, and subsequently a fair income, to those involved. The line proved to be socially, economically and environmentally sustainable. Even though these collections appear to both represent and embrace Westwood's philosophy, can this be said for the entirety of Westwood's collections?

Whilst Westwood is very outspoken and seemingly involved within eco-activism and environmentalism, is she legitimately pioneering and igniting change within the fashion industry? Do her actions align with her ethos? Westwood has been widely criticised, often being accused of ‘greenwash’ - defined by Google as the ‘disinformation disseminated by an organization so as to present an environmentally responsible public image’. Essentially, it is theorised that Westwood has misled consumers, creating a false brand and public image around ecology and environmental activism without adopting the appropriate ethical and sustainable practices. Is Vivienne Westwood simply using environmentalism as a brand tool? Is this just to further and reinforce her antiestablishment and activist brand identity?

First of all, Vivienne Westwood has been known to use PVC, plastic and petrol-based polymers on the runway, all materials which are damaging to the environment. This poses further questions about the materials used in her collections. Are they ethically sourced? Are they sustainable materials? Westwood often talks about her use of ethical and sustainable materials and practices, however there is little evidence of this. Secondly, Westwood continues to bring out vast amounts of collections, completely contradicting her ‘quality over quantity’ policy. Now, this could be an overall criticism of the fashion industry, which works by constantly churning out new ideas and designs. However, Westwood remains complicit in the unnecessary creation of excessive collections. Even if she has (slightly) reduced the amount of collections she’s personally created, is she still creating in overabundance? Is this an effective way of tackling the fashion industry’s colossal carbon footprint? Publications/websites such as ‘Eluxe Magazine’ and ‘Remake’ have criticised Westwood's practices and intentions, theorising that it is a mere marketing tool. Essentially, Westwood is all talk. As a brand, Vivienne Westwood receives the lowest score (grade E aka don’t buy) on ‘rankabrand’ for sustainability. The website states ‘Vivienne Westwood has earned it by communicating nothing concrete about the policies for environment, carbon emissions or labor conditions in low-wages countries. For us as consumers, it is unclear whether Vivienne Westwood is committed to sustainability or not’ (Rankabrand).

Also, is it even possible to exist within the fashion industry and be ethical, sustainable and environmentally friendly? The fashion industry thrives off excessive and rampant consumption and therefore cannot be considered, thus far, as an ethical practice. Fashion has now become an inherently wasteful and damaging enterprise, socially and environmentally. As Jean S. Clarke and Robin Holt suggest ‘Like any other fashion brand, as a firm, Vivienne Westwood is mired in consumption urging those who buy the clothes and accessories into a cycle of seasonal production, promotion, and buying, selling and disposing. Her brand is no stranger to logoed T-shirts, outsourced perfumes, and cheaply stamped jewelry. Yet, there is a growing tension, even contradiction, within the firm which comes with her now growing insistence that consumers should resist consumerism.’ (2015) Is Vivienne Westwood guilty of hypocrisy? You could say that by being in the business of fashion, a business that works by constantly churning out new designs and trends, she is promoting, or even approving, over-consumption.

Another criticism of Vivienne Westwood could be one concerning class. Whilst she campaigns for substantial change within the fashion industry, she does nothing to make this accessible. There is an inherent sense of classism surrounding her brand and ideals. ‘In my view it is worse for someone to come out of a shop with an armful of new T-shirts made in a sweatshop, than it is for a rich lady to buy one beautiful dress’. Whilst this solidifies her target market as being strictly upper class, it also seemingly demonises the working and lower classes, who may not be able to afford ethical/sustainable clothing. Is she shaming those who cannot afford eco alternatives? It appears that, according to Vivienne Westwood, environmental activism and ecology should be reversed for the upper classes. This is apparent, mainly, through her prices. Also, Westwood often discusses subjects such as democracy, economics, philosophy etc. which typically caters to those from an educated and/or privileged background. Considering this, her teachings, if you will, are potentially not accessible to all social and economic classes. A recent post on her website ‘Climate Revolution’ is titled ‘Intellectuals Unite’ (Climate Revolution, 2019), furthering the idea that her brand and values are reserved for educated, privileged and/cultured. There is a perceived sense of academia surrounding her overall message and brand. And regarding her policies, ‘quality over quantity’ may seem like an apt and appropriate policy but could discount many people who cannot afford quality products. Surely if change within the fashion industry was your priority, you would target the masses? Wouldn’t you aim to make ethical and sustainable fashion available to all, thereby changing the fashion industry as we know it? Of course, you must take into consideration that Westwood is in fact a high-end designer, catering specifically for the middle and upper classes, however, if her statement ‘climate change, not fashion, is now my priority’ (Westwood, The Guardian, 2014) is true, surely her focus would shift from the niche to the mainstream, subsequently eliciting the most change?

All criticisms aside, Vivienne Westwood is bringing attention to the wasteful, damaging and often unethical fashion industry. She is creating a dialogue on ecology, which is essential given the severity and threat of climate change. Not to mention other environmental issues such as landfill, deforestation, etc. She’s also donated to various environmental charities and assisted in many campaigns. Perhaps her environmentalism will continue to grow. Perhaps this will eventually pave the way for a better fashion industry; a more reserved and conscious method of consumption. Maybe, at the present, Westwood is mostly talk, but perhaps we just need to start a conversation. To bring ecology to the forefront of society. It’s this education, this conversation, that will eventually lead to change.

Bibliography

Websites - (all accessed from 12/02/19)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vivienne_Westwood

https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2014/feb/08/vivienne-westwood-arctic-campaign

http://climaterevolution.co.uk/wp/

https://eluxemagazine.com/magazine/vivienne-westwood-is-not-eco-friendly/

https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/politics/green-party/11487630/Vivienne-Westwood-defrocked-by-Greens-over-tax-avoidance.html

https://remake.world/stories/news/vivienne-westwood-denounces-her-new-documentary-for-not-telling-her-activist-story-but-do-her-actions-speak-as-loud-as-her-words/

https://rankabrand.org/sustainable-luxury-brands/Vivienne+Westwood

http://activeresistance.co.uk/getalife/Manifesto_ENGLISH.pdf

http://www.bbc.co.uk/newsbeat/article/40260489/vivienne-westwood-gives-her-advice-on-new-designers-and-fashion-waste

https://www.viviennewestwood.com/en/our-approach/

https://ethicalfashioninitiative.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Vivienne-Westwood-SS12-Social-Impact-Report.pdf

Books/Journals/Academic Articles

‘Vivienne Westwood and the Ethics of Consuming Fashion’, Jean S. Clarke, Robin Holt, 2015

0 notes

Text

Further Reading - A Life Less Throwaway: The Lost Art of Buying for Life by Tara Button

As part of my further reading, I have read ‘A Life Less Throwaway: The Lost Art of Buying for Life’ by Tara Button, the founder and CEO of ‘Buy Me Once’ - an online shops and directory for quality, long-lasting and sustainable products. The book explores consumerism and materialism in modern society; Button examines advertising, marketing and other variables that foster over-consumption and ideologies of materialism. The book, instead, pioneers for mindful consumption. Proposing we seriously evaluate our purchases and prioritize longevity, quality and sustainability when regarding our products. Ultimately the book urges us to reinvent the way in which we consume.

The book thoroughly investigates advertising and marketing’s role in our consumption. Having worked in the advertising industry, Button is aware of all the manipulations companies employ to ensure sales, and by extension, profits. Button analyses how advertising/marketing creates, and thrives, off a culture that makes us feel inadequate or lacking. ‘We’re being manipulated to feel that our current possessions (and by extension ourselves) are inadequate’ (Button, 2018, xii). By making us feel insufficient and/or incomplete, they are compelling us to buy. We buy to fill a void, to make us feel complete. It all comes down to the ideology that material things will make us happy and/or worthy. As social creatures, we crave social acceptance, however modern society has placed too much value on the approval and opinion of others. This need for validation cultivates materialism - ‘The messages we see in ads and social media channels perpetuates a myth that having things or looking a certain way makes us worthy of love and admiration...we start to focus on our looks and achievements and buy high-status items that others will admire. However, any admiration or connection we gain is on a shallow level, and because it isn’t based on anything authentic, it leaves us feeling disconnected and unsatisfied’ (Button, 2018, p.7). Essentially this is just a tool used by brands and companies to lure us into buying. We need to realize our value does not lie, nor is it synonymous with, our stuff.

There are many tactics used within the advertising and marketing industry. One discussed heavily by Button is planned obsolescence – the deliberate act of making products to break. The quality of products has drastically reduced over the years; materials are cheaply sourced in order to maximize profits, products are mass produced as quickly as possible to maximize sales and advertising and branding is at the forefront of the business model to encourage use to buy products. ‘Our whole houses, our whole lives, have become stuffed full of things that let us down, cause our stress levels to skyrocket and our bank accounts to empty. But precisely because these things are poorly made or faddy, perversely we are compelled to buy more’ (Button, 2018, ix). Planned obsolescence is again a ploy used to get us to buy more. We regularly need to replace broken items, and this quick turnaround increases profits. ‘The commercial world does everything it can to tempt us away from longevity, but that only serves its ever-hungry self, not us, the people who have to deal with the broken zips, rattling washing machines and rips in the crotches of our jeans’ (Button, 2018, p.4). This is something, sadly, we have come to accept as nowadays we prioritize convivence and price. Whilst initially we are thrilled at the idea of cheap items, this model actually encourages us to spend more over time and leaves us dissatisfied with, quite frankly, shoddy products.

Then there is psychological obsolescence. ‘Psychological obsolescence is a technique used by companies to persuade us to replace the products we own, even if they still work perfectly well. Over the last few decades companies have conditioned us to see things as temporary and throwaway. They keep us obsessed with the new.’ (Button, 2018, p.27). We constantly upgrade our possessions for the newer and/or trendier. Much of the time, this is linked to appearance and social approval. New products often come with high status; they are an indicator of style and wealth. We have come to view material things as disposable. This is, however, an unsustainable and wasteful way of consumption. ‘Mindless consumerism is pushing our poor planet to crisis point’ (Button, 2018. p.6), this way of consuming is having a disastrous and irreversible environmental impact. This volume of industrial mass production is severely polluting. One way to tackle climate change and pollution is to change the way in which we consume. We must stop over-consuming and overindulging material things. ‘The way we things is broken and the things we buy are breaking. But we can break this cycle. If we buy things we love and buy things that last, and then take care of them, we might just save the world’ (Button, 2018, p.236).

Button also explores the extent of advertising in modern society. Advertising is more prominent in society than ever before - ’we now see and hear an estimated 362 ads a day and over 5,000 brand exposures’ (Button, 2018, p.44). With the growth of digital technologies and social media, it is easy to advertise than ever before. It has even paved way for entirely new forms of advertising, such as social media influencers. These forms are subtle and often work subconsciously. We often don’t realize we are being sold to through social media platforms – what with personalized ads, undisclosed ads and haul videos. ‘Scrolling through idealized pictures of other people's lives increases our anxiety and doesn’t help us feel grateful for what we have’ (Button, 2018, p. 63) instead they function, again, to make us feel inadequate and incomplete, and ultimately buy.

Button also explores identity in relation to our possessions. Much of my further reading thus far has been dismissive of identity in terms of materials objects. A common opinion amongst minimalism and mindful consumers is that buying things akin to your identity is trivial and unimportant, as, ultimately, your things do not reflect or retain you. Whilst this is true to an extent, your material possessions do not define you, it must be said that buying things that are true to your sense of self is integral to mindful consumption. When evaluating our consumption, should we not consider personal style, values and character, as well as function? Would this not ensure our love for our objects and our care for them as such? When discussing mindful consumption, Button says ‘this meant that the possessions I ‘curated’ automatically started to reflect the deeper and more stable elements of my character, values and personal style’ (Button, 2018, p.4). Essentially, mindful consumption led her to make purchase based on her own identity and needs, rather than advertisements, trends or social status.

Overall, Button makes a compelling, informed and analytical investigation into the world of consumerism. She discusses all elements of our consumption with depth and consideration. I have found ‘A Life Less Throwaway’ to be the one of the most educational pieces of further reading in this project thus far. She perfectly captures and explains the exploitative and manipulative tactics adopted by brands to secure sales. She explores everything that is wrong with modern day consumption and the steps we can take towards a more mindful, ethical and sustainable way of consuming. ‘A life less throwaway becomes a simultaneously simpler and richer life, because the focus is off consumption and on what really matters’ (Button, 2018, xiii).

Button, Tara. A Life Less Throwaway – The Art of Buying for Life: Harper Collins Publishers, 2018

https://uk.buymeonce.com/

0 notes

Text

Further Reading - ‘The Year of Less’ by Cait Flanders

As part of my further reading on minimalism and consumerism, I read Cait Flander’s memoir ‘The Year of Less’. The memoir documents Cait’s life during a yearlong spending ban. She explores consumerism and shopping as a coping mechanism, drawing on her past addictions and other unhealthy habits. She also explores conscious/unconscious consumerism through her experiences of mindless shopping and accumulation. Essentially, the memoir explores the transition from binge consumer to mindful consumer.

The book documents each month of the yearlong spending ban, allowing us to join her journey to mindful consumption. She details and reflects on her spending habits throughout each month. It is evident that the shopping ban teaches her all about mindful consumption. Throughout the memoir, she muses on the lessons learnt from the experiment and ultimately how they have led her to live a more intentional and fulfilled life. Unconscious consumerism is so deeply ingrained in modern society – we are surrounded by advertising, manipulated by marketing and sale tactics, plagued by an ideology that tells us material things will make us happy – in short, we are constantly told to ‘buy’. By setting rules regarding her spending, Cait was forced to think about her consumption and ultimately evaluate and consider her purchases. What came from this was a more informed and intentional way of consuming.

This change in shopping habits also inspired her to reconsider material possessions. Throughout the experiment she got rid of 75- 80% of her belongings (2018, p.170), only keeping what was truly necessary and/or functional. This experiment taught her wholly about mindful consumption – not only did she readdress her shopping habits, she also reevaluated what she already owned/consumed. What did she need? What did she use? What added value to her life? Of the experiment, Cait said ‘if I had simply stopped shopping for a year, I might have learned a lot about myself as a consumer. And if I had simply decluttered my home, I might have learned a lot about my interests. But doing both challenges at the same time was important, because it forced me to stop living on autopilot and start questioning my decisions’ (2018, p.163). In other words, by both addressing her shopping habits and her material possessions simultaneously, Cait became a conscious consumer: looking at all aspects of her consumption.

In addition to exploring mindful consumption, Cait thoroughly explores consumerism as a coping mechanism. We are all familiar with the concept of retail therapy – the act of shopping to make oneself feel better. However, we may not realize how entrenched this notion is in modern culture. We are taught, through various forms or media and advertising, to numb pain with material possessions. Similarly, we are taught to reward and/or ‘treat’ ourselves with material possessions. Ultimately, whatever the emotion, we are taught to buy. This goes hand in hand with the ideology - so prevalent in our society - that material things equals happiness. Cait specifically looks at buying materials things as a form of distraction or temporary fix. As a way of dealing with one’s emotions or rather, avoiding one’s emotions. ‘One of the greatest lessons I learned during these years is that whenever you’re thinking of binging, it’s usually because some part of you or your life feels like it’s lacking – and nothing you drink, eat or buy can fix it. I know, because I've tried it all and none of it worked. Instead, you have to simplify, strip things away, and figure out what's really going on. Falling into the cycle of wanting more, consuming more, and needing even more won’t help. More was never the answer. The answer, it turned out, was always less.’ (Flanders, 2018, p. 170) She also discusses other forms of consumption, namely food and alcohol, and how they are also used as tools to suppress emotion. She discusses her unhealthy relationship with food and alcohol and how she used them as a ‘crutch’ during hard times in her life. ‘I kept living. I felt things and I kept living. I didn’t numb them with food or alcohol. And I didn’t shop. It wasn’t going to help. It had never actually helped before, and it wasn’t going to help this time either’ (Flanders, 2018, p.49) Whilst she primarily talks about material consumption, she does often discuss her relationship and dependency with alcohol and her decision to go sober. Ultimately, she says that this experienced helped her a lot with the spending band and was therefore relevant. And whilst I agree, it does sometimes feel like alcohol and its consumption is the main topic of the book.

Identity plays a pivotal role in our consumption and Cait does acknowledge this in her memoir. ‘I filled the shelves with books and knick-knacks - curated objects found in overpriced stores that screamed ‘me’’ (Flanders, 2018, p.47). She considers how we express our identity through material possessions. However, she does recognize that this often is a persona – an image of ourselves for the perception of others. How do we want others to view us? ‘I had to accept that I was never going to be the type of person who read, wore or did these things...I started with my books and asked myself a question I'd never considered the answer to before: who are you buying this for: the person you are or the person you want to be?’ (Flanders, 2018, p.118) I think this is immensely important in the age of social media. We are obsessed with image. We curate ourselves – often an idealized version of ourselves. And we present this to others through our belongings and all forms of social media. Our Instagram's are filled with images of the latest clothing and gadgets, people showing their status, how cool they are, how trendy they are. More often than not, and specifically in this day and age, our possessions aren’t an accurate reflection of ourselves. Cait draws on this by asking herself who she is buying for – herself or others?

Overall this is an extremely interesting and insightful book on conscious consumerism. I wasn’t expecting a memoir to be as educational – you learn a lot about consumerism throughout. I also found it quite inspiring – it is encouraging about mindful consumption, detailing how it is beneficial mentally and financially. The experience clearly made a last impact on her as she extended the shopping ban to 2 years and even continues to document her journey of mindful consumption on her blog.

Flanders, Cait. The Year of Less: Hay House Inc. 2018

https://caitflanders.com/

0 notes

Text

Goodbye Things : On Minimalist Living - Fumio Sasaki

Minimalism

Minimalism is a social movement that rejects modern ideologies of consumerism and materialism, instead promoting a life of meaning and purpose. It is also often referred to as intentional living – the act of living mindfully. When it comes to objects, minimalism teaches conscious consumption; only own things which have a function/purpose and that add value to your life. Minimalism focuses on what is ‘important’ - relationships, happiness, growth, community - as opposed to the mindless accumulation of material possessions.

‘Goodbye, Things: On Minimalist Living’ - Fumio Sasaki

‘Goodbye, Things: On Minimalist Living’ is an essay by Fumio Sasaki on the philosophy of minimalism. Sasaki explores the benefits of living a minimalist lifestyle – ultimately how by having less, we can live happier and more meaningful lives. The essay also acts as a guide to minimalism, providing insight and advice on how discard unnecessary possessions and in turn live a more purposeful life.

He begins by exploring our relationship with the material; how our belongings have become synonymous with our identity and/or an indicator of wealth and status. Our possessions are mostly for appearance - a means of representation and symbolism. Throughout the book, Sasaki explores how society’s obsession with appearance has led to rampant consumerism. He discusses how social conventions and pressures, self-worth, comparison, advertising and social media all contribute to our unhealthy relationship with the material. Essentially, we live in a society dominated by self-image and in doing so ‘society today puts too much weight on material objects’ (Sasaki, 2017, p.153). Sasaki rightfully critiques modern day society and its ideologies. We do place too much meaning on our image and in turn on our material possessions. They do not have the power to dictate our self-worth and similarly, will never retain our identity. However, I don’t think it is inherently wrong to want your possession to relate to your sense of self. I think we should personalize our belongings – buy what makes us happy, what adds value to our lives, what speaks to us. The key is to buy for yourself, and not for the sake of others.

Sasaki also attributes materialism to our desire for happiness and our belief that material things will achieve this. We continue to buy things because we believe we can buy into happiness. This idea is enforced through media and advertising. Their priority is in profits; they are aware that the ‘quintessential energy that drives us is the desire to be happy’ (Sasaki, 2017, p25) and will use this as their selling point. Sasaki acknowledges how this ideology can leave us feeling unhappy and dissatisfied - how we begin to focus on what we lack, leading us to buy more and live in excess. Ultimately, ‘we think the more we have, the happier we will be’ (2017, p23).

Moving forward, Sasaki goes on to detail how getting rid of unimportant possessions made him genuinely happier. He began to get overwhelmed by the presence and volume of his belongings, finding himself trapped in the viscous cycle of consumerism. He states that by getting rid of his belongings he has more time, space and energy – which he can allocate to what truly matters. As Sasaki says, ‘minimalists are people who know what’s truly necessary for them versus what they may want for the sake of appearance’ (2017, p44).

I wholeheartedly agree with the teachings of minimalism and found this essay to be a good introduction. Sasaki makes some great points throughout the essay, particularly about society. However, some points were quite rudimentary, and I would have liked to have seen him build a more in-depth critique of consumerism and materialism, and potentially capitalism. He only briefly discusses the environmental impact of consumerism, which I believe to be a pivotal when discussing our relationship with the material. He also makes some arguments which seem to completely contradict minimalism. One excerpt urges readers to ‘discard it even if it sparks joy’ (Sasaki, 2017, p.145). And does this not go against everything that minimalism stands for? Minimalism is about owning things that have purpose and add value to your life - which would also include things that add joy? Considering that the entire essay is about living a happier and more meaningful life, this excerpt seemed incongruous with the rest of the teachings. As I previously mentioned, this essay would serve well as a personal account and basic introduction to minimalism as it isn’t the most analytical text.

0 notes

Text

The Environment and Consumerism

Environmental Impact of Capitalism, Consumerism and Material Cultures

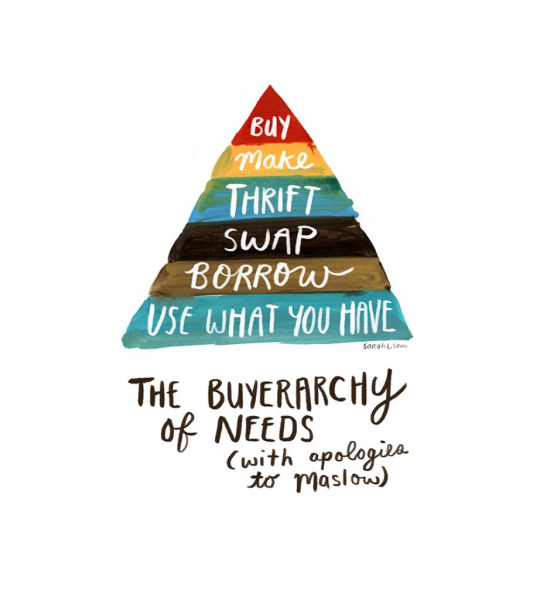

Following my recent research in to thrift and the previous set reading ‘This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs. The Climate’, I have decided to further explore the environmental impact of consumer culture. Consumerism and capitalism have a significant impact on the environment, with both being direct causes of climate change, global warming and pollution. In other words, our consumption is having disastrous, and potentially irreversible, effects on the planet. Whilst I am looking at consumption particularly in relation to identity, I think it is vital to also consider the further implications. Consumer and material cultures impact the environmental as well as the social. I feel such research will also help inform the next part of my project which aims to look more closely at sustainability and anti-consumerism, or more so mindful consumerism. I plan to create another zine – a guide to thrift shopping and ethical consumption, and a series of anti-consumerism and mass production protest posters. I would also like to explore creating protest t-shirts and tote bags if possible – ones which promote sustainable, ethical and conscious consumption. I will begin my research by investigating consumerism and its environmental impact, moving on to look at public response, such as the minimalism movement, ethical brands and campaigns.

Documentaries

Stacey Dooley Investigates: Fashions Dirty Secrets (2018)

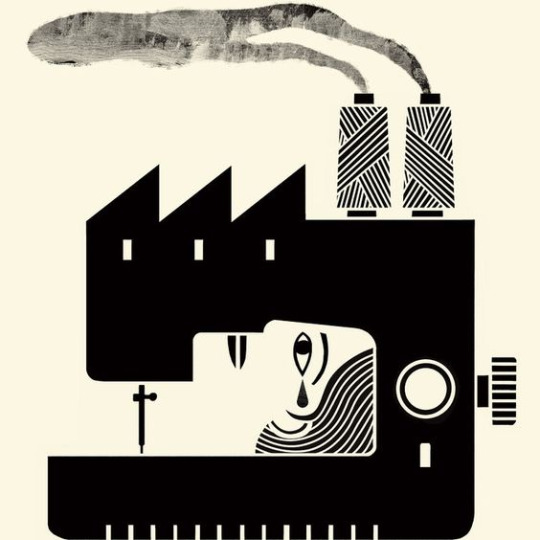

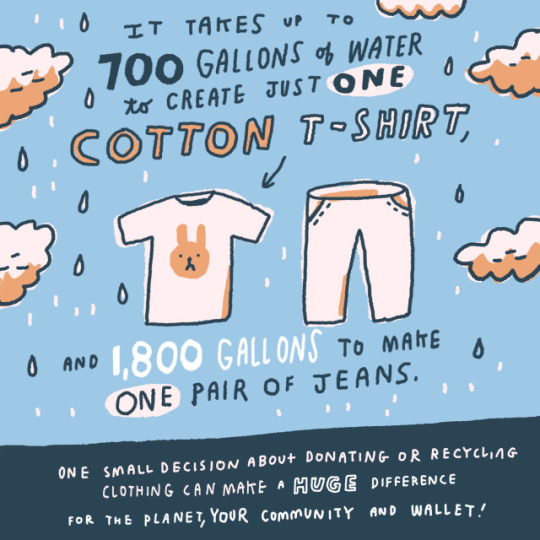

‘Stacey Dooley Investigates: Fashions Dirty Secrets’ is a documentary film that delves into the dark world of the fashion industry, specifically looking at the damaging environmental impact of fast fashion. Fast fashion is the process of manufacturing and distributing clothing as fast and cheaply as possible in order to fit trends and beat competing retailers. Essentially, companies want to create and sell as many products as possible, as quickly as possible. This rapid turnaround and intense volume of production is problematic in many ways. Fast fashion breeds excessive consumption; not only do we have an immense array of products readily available to us, but corporations also employ marketing strategies that lure us into buying more, and often things we don’t need. Fast fashion also makes things appear disposable – we are quick to replace things, regardless to whether it’s necessary. We subscribe to trends - getting rid of things simply because they are no longer ‘in fashion’. This consumeristic and materialistic behavior is extremely wasteful and unsustainable. Landfills (where unwanted clothes and possessions end up) are brimming – filling up quickly. We cannot continue to create more landfill sites – it is environmentally damaging and reduces the use of soil. Rampant consumerism and excessive manufacturing are extremely harmful to the environment - industrial mass production is severely polluting, with fashion being estimated as the second biggest polluter in the world (almost on par with the oil).

The documentary goes on to explore examples of environmental catastrophes directly related to the fashion industry. The Aral Sea is one example and is a particularly poignant and painful consequence of our unbridled consumption. The Aral Sea is, or rather was, an endorheic lake bordering Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan that shrunk disproportionately since the 1960’s. This was due to the expansion of the canal that drained that Aral Sea in order to manufacture cotton. This had a substantial impact on the environment and economy. Chemicals used in the production of cotton (and other industrial ventures) heavily polluted the area, contaminating the water supply and local farm land. The shrinkage of the sea has also cause significance weather problems, such as harsh winds that create dust storms. Both have had a serious impact on the public health, causing the death toll and child mortality to rise. The Aral Sea once housed an immense fishing industry which has now obviously collapsed. This has caused unemployment and economic difficulties. It is hard to see how detrimental our consumption is to the environment. Another case in the documentary is the Citarum River. The Citarum River is the longest river in Indonesia and supposedly the most polluted in the world. Thousands of industrial and textile factories border the river, releasing toxic chemicals, heavy metals and waste into its canal. This is extremely harmful to those who live near the river as they have no access to clean water, causing a magnitude of health problems. Most factories in this area export to the UK. Companies source outside of the UK as it is cheaper and there are less rules and regulations. It is shocking to see the lack of responsibility from the brands. Many brands even refused to talk to Stacey for the documentary showing their lack of care from the environment and their dishonesty to the public.

Towards the end of the documentary Stacey meets up with some fashion influencers to educate them on their consumption and their damaging environmental contribution. I think this is such a vital part of the documentary. Although it isn’t as shocking and powerful as the scenes at the Aral Sea and Citarum River, influencers are such a huge part of modern society, and a huge part of the problem. Influencers are now another marketing/advertising tool and have added enormously to throwaway culture. The popularization of haul videos glamourize and normalize materialism and excessive consumption, as well as add pressure to wear new and on trend. I think that influencers must take responsibility and think about what they are actually promoting. Not only does the fashion industry need to change, but also media industries. The documentary ends by stating that it is up to us, as a society, to make a change. Ultimately, we must force the fashion industry to change. We desperately need to change our shopping habits and work towards mindful, ethic and sustainable consumption. This was an incredibly powerful and informative documentary. Whilst I was aware of the environmental impact fast fashion has, I had no idea of its extent. The documentary is extremely thought-provoking, successfully making you examine your contribution and consumption. The topic is so important right now. We are running out of time to save our planet, and one solution is to readdress and reinvent our production and consumption of material things.

https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b0bn6034

The True Cost (2015)

‘The True Cost’ is a documentary film that explores the negative social and environmental implications of the fast fashion industry. The documentary answers the question – where does our clothing come from? And what is the true cost?

It begins by discussing the modern fashion industry – one dominated by excessive consumption and greed. In recent years, the fashion industry has gone through a colossal change; we now outsource to developing countries and partake in global trade, meaning prices have deflated. Whilst this may seem good to us consumers, this change in production and distribution often compromises the environment, public health and human rights. Unfortunately, fast fashion is only in the interest of profit. Trends and planned obsolescence (the act of making products to break) ensure that we are spending as much and as often as we can – so even if products are effectively cheaper, there is still increase in profits. Regardless of the consequence.

Unlike ‘Stacey Dooley Investigates’, ‘The True Cost’ focuses more on the social impact of the fashion industry – how it employs slave labour and unethical practices. It details the 2013 Rana Plaza collapse in Bangladesh, a tragedy that killed over 1,100 people, many of whom were garment workers. Bangladesh is the second cheapest place in the world to source clothing, making it a prominent area within the fashion industry. The Rana Plaza was a commercial building and therefore wasn’t equipped to house textile factories. Additional floors were also added to keep up with the growing demand from the fashion industry. Due to this, the building structure started to crack – concerns were raised, and the building was evacuated on the 23rd April 2013. However, the building was deemed safe and all workers were ordered to return to work the next morning. That morning, the building collapsed – making it the biggest garment industry accident in history. The documentary goes on to explore the aftermath of this disaster and the industry that caused it.

Ultimately the fashion industry is employing slave labour. The fashion industry is one of the biggest and most profitable industries in the world which begs the question – why aren’t they paying their workers a fair wage? Or, why aren’t they providing safe and clean working environments? Of course, they don’t officially employ the garment workers from other countries (which make it easy for them to escape responsibly) but they still have a duty to ensure they are sourcing ethically. The harsh truth is that this would cost money and lower their profits, which they aren’t willing to do. They even try and excuse and justify their sourcing – they say that they provide jobs and help developing countries and economies. This is such a shocking part of the documentary as it clearly shows how money is valued over all else.

The documentary talks to various people in the industry, including ethical fashion companies, garment workers in Bangladesh and cotton farmers. It is revealed in the documentary how garment workers are beaten - especially if they protest/campaign for a fair wage, and how they are exposed to dangerous chemicals. The cotton farmers discuss how many pesticides and chemicals are used for modifying crops, which are harmful to the environment, and subsequently harmful to those who reside in the area. Such pesticides and chemicals used in agriculture are highly contaminating and deeply effect human health, leading to birth defects, cancer and mental health issues. The documentary speaks to a doctor in Bangladesh who attributes many of the health problems throughout the country to the chemicals used within the fashion industry. Such modification of agriculture has also led to the monopolisation of seeds, which has proven financially difficult to farmers. According to the documentary, in the last 16 years more than 250,000 farmers committed suicide in India. The industry also causes water and river pollution, which significantly reduces clean water access.

After exploring the effects in the developing world, the documentary investigates it impact in the developed wold. It goes on to explore the consumeristic values that plague our society. It proposes that the more materialistic, the unhappier we are, looking at advertising and the societal ideology that money buys happiness and constitutes worth. Much like ‘Stacey Dooley Investigates’, ‘The True Cost’ explores haul culture and social media. Influencers are now another form of marketing/advertising and contribute hugely to consumer culture. The growth of technology and introduction of social media has meant we are constantly, and unconsciously, surrounded by advertising. The rise is hauls are perpetuating trends and throwaway fashion. This leads to an increase in landfill both in developed and developing countries, where donations often end up. The rest of the documentary discusses the vital need for change and explores what is currently being done. They talk to Stella McCartney and Livia Firth, pioneers for change within the fashion industry. Essentially, we need to reinvent the fashion industry and the way in which we consume. Fashion should not be disposable, nor should it ignore and compromise human rights and safety or the health of the planet.

The true cost pioneers for an ethical and eco-friendly fashion industry. What we can learn from this documentary is that our current fashion industry and insatiable consumption is damaging the planet and is categorically immoral and exploitative. It is an essential documentary, one which I would highly recommend. It includes a lot of emotionally sensitive content, but it is necessary – we need to be aware of where our material things come from. We need to change. We as consumers have the power to change the whole system. It is imperative that we consider our contribution and act accordingly.

https://truecostmovie.com/

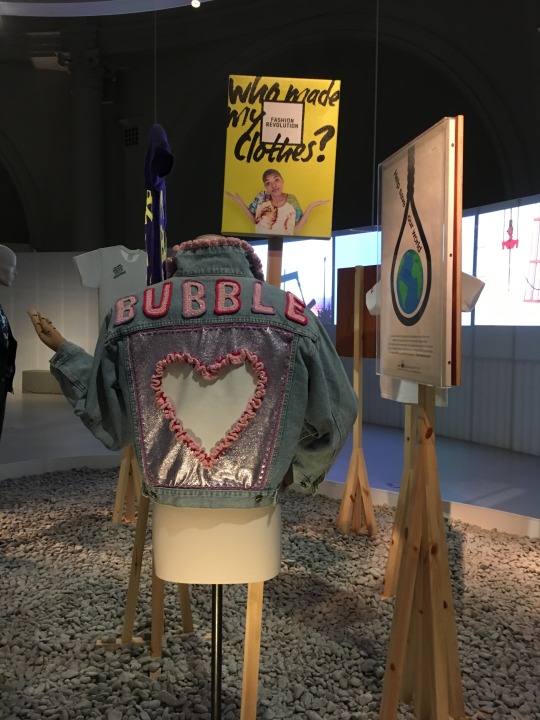

Exhibitions

V&A – Fashioned from Nature

For my research I visited the Victoria and Albert Museum – their current exhibition ‘Fashioned from Nature’ explores the fashion industry, looking specifically at its impact on nature. It guides you through history, through the evolution of fashion, technologies and materials. The downstairs focuses on past fashion, from the 1600’s onwards; it explores the materials and techniques used, mostly ones that involve animal cruelty, chemical use and industrial processes. Many materials used were sourced from animals, often leading to their endangerment. Not only were the materials used unethical, but the processes to create such materials were highly polluting. As Britain became more industrialized, the production of fashion increased. What came next was the invention of departments stores, advertising and other forms of media, all leading to the growing expansion of the fashion industry. Clothes became cheaper, disposable, and at the price of the environment. A variety of social problems also ensued – slave labour, health issues, lack of clean drinking water etc.

The upstairs focuses on modern fashion, specifically new and sustainable fashions. It looks at new fabrics and materials, as well as new processes that are ecofriendly. It also looks at environmental activism and public response – how we can make the fashion industry more ethical, sustainable and environmentally friendly.

The exhibition was beautifully curated and executed. There was an immense about of detail in the exhibition – even the soundtrack was incredibly considered, it used a variety of sounds from nature including bird songs, whale sounds etc. Every piece contributed greatly to the wider message. It also flowed extremely well, with the downstairs being a shocking and thought-provoking exploration of the prolonged environmental impact of the fashion industry, and the upstairs being an inspiring observation on how we can incite change. It really makes you contemplate your social and environmental responsibility. This exhibition is completely necessary what with fast fashion and modern-day materialist values. It asks important questions about our consumption and its impact. What are we doing to our planet in the name of fashion? How can we reinvent the fashion industry to be more sustainable? I would urge anyone to visit this vital exhibition. We all have a duty to educate ourselves and protect our planet and community.

https://www.vam.ac.uk/exhibitions/fashioned-from-nature

Whilst both the documentaries and the exhibition look specifically at clothing, it is also true for all material objects. Our rampant consumerism and the mass production of all material things is having dire consequence on the planet. We are simply producing too much and disposing of too much. We desperately need to change the fashion industry, but also the way in which we treat and create all material things.

Other Resources

Articles

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2010/jun/21/overconsumption-environment-relationships-annie-leonard

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-44968561

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-45745242

https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2018/feb/10/shop-less-mend-more-making-more-sustainable-fashion-choices

https://www.theguardian.com/fashion/2018/oct/07/cheap-fashion-threatens-planet-vloggers-online-savioursdisposable-fashion-environmental-damage

https://www.theguardian.com/business/2017/oct/30/to-cure-affluenza-we-have-to-be-satisfied-with-the-stuff-we-already-own

Campaigns

https://www.lovenotlandfill.org/

https://cleanclothes.org/

https://www.fashionrevolution.org/

https://www.greenpeace.org/international/

https://www.bracusa.org/

https://www.fairtrade.org.uk/

https://www.sustainyourstyle.org/

https://waronwant.org/

www.fashionrevolution.org

Mitch Blunt

Mike Lowery

Sarah Lazarovic

1 note

·

View note