Link

0 notes

Text

Yoko Ono ‘Sky Tv’

https://hyperallergic.com/328294/yoko-onos-art-remote-japan-traveling-far-see-sky/

0 notes

Text

Postmodernism

Postmodernism can be seen as a reaction against the ideas and values of modernism, as well as a description of the period that followed modernism's dominance in cultural theory and practice in the early and middle decades of the twentieth century. The term is associated with scepticism, irony and philosophical critiques of the concepts of universal truths and objective reality.

https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/p/postmodernism

0 notes

Text

Formalism In Art

Formalism describes the critical position that the most important aspect of a work of art is its form – the way it is made and its purely visual aspects – rather than its narrative content or its relationship to the visible world. ... All this led quickly to abstract art, an art of pure form.

https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/f/formalism

This form of art began to be challenged by Postmodernism.

0 notes

Text

Structuralism in Art

Broadly speaking, Structuralism holds that all human activity and its products, even perception and thought itself, are constructed and not natural, and in particular that everything has meaning because of the language system in which we operate.

0 notes

Text

Non-representational Theory: Nigel Thrift

“made up of all kinds of things brought into relation with one another by many and various spaces through a continuous and largely involuntary process of encounter” (Thrift 2007: 7)

0 notes

Text

Participation and Audience Involvement

Marcel Duchamp, a pioneering artist and leading figure in the Dada movement, argued that both the artist and the viewer are necessary for the completion of a work of art. He posited that the creation of art begins with the artist—often working in isolation in the studio—and is not completed until it is placed out in the world and viewed by others. “All in all, the creative act is not performed by the artist alone; the spectator brings the work in contact with the external world by deciphering and interpreting its inner qualifications and thus adds his contribution to the creative act,” he once wrote.1

As Duchamp was making his case in the late 1950s, artists were beginning to present work that not only reflected their recognition of this relationship, but also their radical reinvention of it. They crafted performances, events, instructions, and happenings that invited—and sometimes required—people’s participation. By soliciting such active involvement, artists were attempting to break down traditional and perceived barriers between themselves, their work, and the viewer.

Artists engage and collaborate with audiences in many different ways today. By opening up their process of creation to others, they give up a measure of control over their work, and give over to chance and to trust in the viewer-turned-participant. And the work of art, in turn, becomes a two-way exchange.

0 notes

Text

Tate- Claire Bishop ‘But is it installation art?’ 1 Jan 2005

The variety of work detailed above demonstrates that installation art means many things. But, as Gillick observes, to speak of its ‘end’ is extremely difficult, as the term describes ‘a mode and type of production rather than a movement or strong ideological framework’. Despite the dearth of a manifesto, one can nevertheless point to a persistence of certain ideas in the work of contemporary artists who continue its tradition. These values concern a desire to activate the viewer – as opposed to the passivity of mass-media consumption – and to induce a critical vigilance towards the environments in which we find ourselves. When the experience of going into a museum increasingly rivals that of walking into restaurants, shops, or clubs, works of art may no longer need to take the form of immersive, interactive experiences. Rather, the best installation art is marked by a sense of antagonism towards its environment, a friction with its context that resists organisational pressure and instead exerts its own terms of engagement.

0 notes

Text

Art becomes interactive when audience participation is an integral part of the artwork. Audience behaviour can cause the artwork itself to change. In making interactive art, the artist goes beyond considerations of how the work will look or sound to an observer. The way that it interacts with the audience is also a crucial part of its essence. The core of such art is in its behaviour more than in any other aspect. The creative practice of the artist is, therefore, quite different to that of a painter. A painting is static and so, in so far as a painter considers audience reaction, the perception of colour relationships, scale or figurative references is most important. In the case of interactive art, however, it is the audience’s behavioural response to the artwork's activity that matters most. Audience engagement cannot be seen just in terms of how long they look at the work. It needs to be in terms of what they do, how they develop interactions with the piece and such questions as whether they experience pain or pleasure.

0 notes

Text

Engaging Strangeness

What is the public art museum’s role in enhancing hesitant viewers’ engagement with contemporary art, especially its more challenging and conceptual aspects? In considering this question, the notion that contemporary art is too difficult for general audiences to engage with directly is refuted. It is suggested that the capacity for viewers to make sense of contemporary art, understood as the discursive practices that have come to the fore since the 1960s, is hindered not by the art but by the art theory that hesitant viewers employ. As representational and formalist aesthetic codes remain the dominant modes of responding to art, for the art museum to become more inclusive, there needs a greater emphasis on discursive approaches to experiencing art. From an examination of claims made across disciplines that advocate discursive practice, including George Hein’s constructivist museum, Helen Illeris’s performative museum and Jacques Lacan’s psychoanalytic conversation, a strategy for the enhancement of the experience of contemporary art for the hesitant or disconnected viewer is proposed that involves reorienting the role of the public art museum from expert speaker to expert listener.

http://www.newaudiencesforart.com/wp-content/uploads/Engaging-Strangeness-in-the-Art-Museum.pdf

0 notes

Text

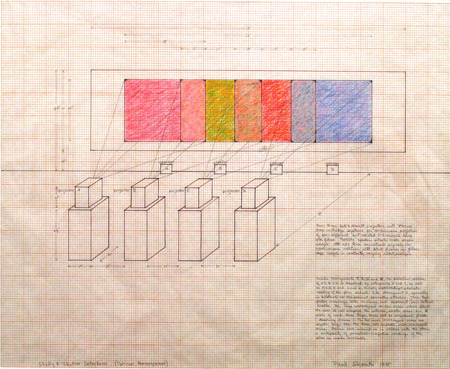

Paul Sharits ‘Shutter Interface’

http://arika.org.uk/archive/items/kill-your-timid-notion-07/shutter-interface

Paul Sharits, Study 4: Shutter Interface (optimal arrangement), 1975, ink and coloured pencil on paper, 46x58 cm

Four looped films of varying lengths are unspooled and respooled in jewel-like swathes of colour interspersed with single black frames, creating the flicker effect Sharits – who died in 1993 – was the first to explore in colour films. The images thrown onto the wall overlap at their edges, producing ghostly paler bands where hues mix within the wide polychrome rectangle, complicating patterns that emerge like waves, horizontal pulses or, more eerily, cards shuffled by invisible hands. When the black interstices disrupt the chromatic flood, the soundtracks emit high-frequency, cicada-like tones via speakers placed underneath the projected images, aurally mirroring the whirling shutters.

To best view an installation of Shutter Interface, you have to duck before the line of whirring machines and sit on the floor in front of them. Even when stationed between the projectors and the corresponding images, however, you get the sense of being a witness to a wrenching event, both a viscerally engaged and a detached observer. As Rosalind Krauss noted of another four-projector Sharits installation, Soundstrip/Filmstrip (1972), the panoramic field formed by the overlapping images echoes the Cinemascope format, but the glorious illusion typically associated with widescreen movies is continuously disrupted by the insistently sculptural projectors and bases. Instead of being enveloped, we are, as Krauss wrote, ‘at a tangent to the illusion, forcibly aware of the generative pair: projector/projected; aware, that is, of the mechanisms that are closer to the birth of the illusion.’ Sharits viewed such works as ‘locational’ installations, which he intended to be shown outside of the context of the cinema and saw as having ethical dimensions.

Before Modernism, and even in most modernist art apart from Minimalism and Formalism, artists worked with a sympathetic understanding of the needs of the public. From the beginning of the century many artists have been fascinated at one time or another by the idea of a more perfect union between art and viewer. To suggest that serious artistic consideration of the public is new, or to argue that physical participation can establish a relationship with the public that is more honest, more complete and more respectful of its ''uniqueness and subjectivity'' does not make a lot of sense.

Art depending upon our physical participation in order to function tends to have little imaginative substance. As entertaining and clever as the objects in this exhibition are, they tend to stop the imagination, not inspire it. The most engaging objects are those that do not depend upon our physical involvement.

0 notes

Text

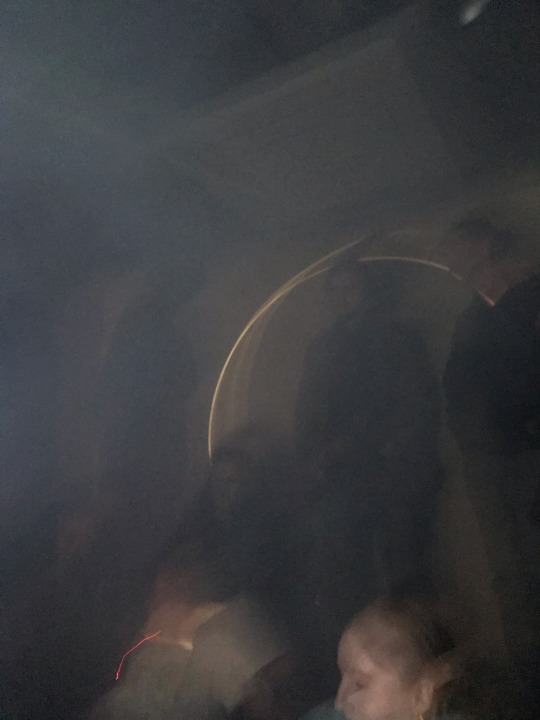

My Own Expierience of Antony McCall’s ‘Line Describing a Cone’ (12 February 2018)

Because of the way it makes us aware of space, aware of our relation to a particular space and aware of sound as something that affects us, and is why having sound isn't particularly necessary.

1 note

·

View note

Text

‘Installation art of the 1980s, by contrast, was more visual and lavish, often characterised by giganticism and excessive use of materials.’

0 notes

Text

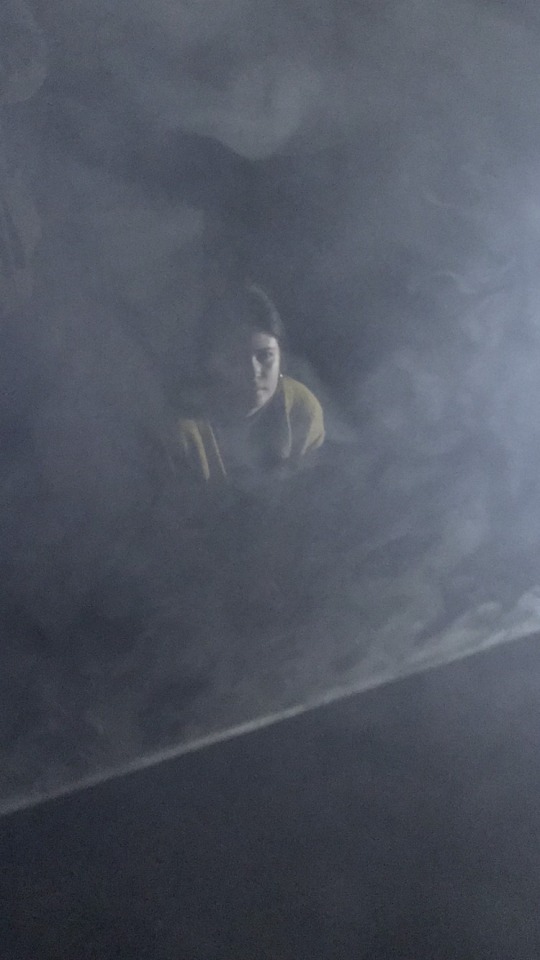

ANTHONY MCCALL

‘Sculptural light’

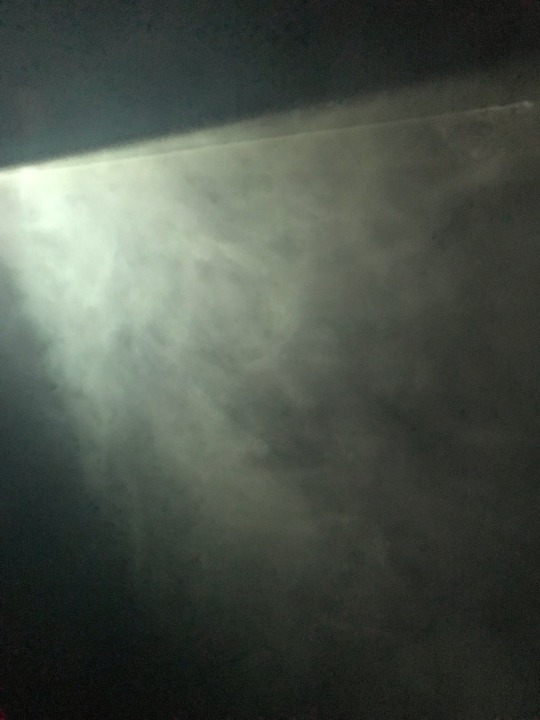

The Observer - “ McCall, now 71, effectively decoupled cinema and image in his celebrated 1973 piece Line Describing a Cone, projecting a conical shaft of white light across a pitch-black gallery. Its shape was made visible with a haze machine, like the beam defined by cigarette smoke in an old movie theatre.”

“It is a mysterious combination: the beams streaming across the gallery, their surfaces (as it seems) like diaphanous veils, turning clouds or ever-changing weather, balanced against the pure graphic force of the light concentrated on the screen. How frail is this light that makes our world visible, and yet how strong: that is the wonder McCall brings to mind with his works, so simple, poetic and strange.”- Laura Cumming

The pioneer work ‘Line Describing a Cone’, 1973

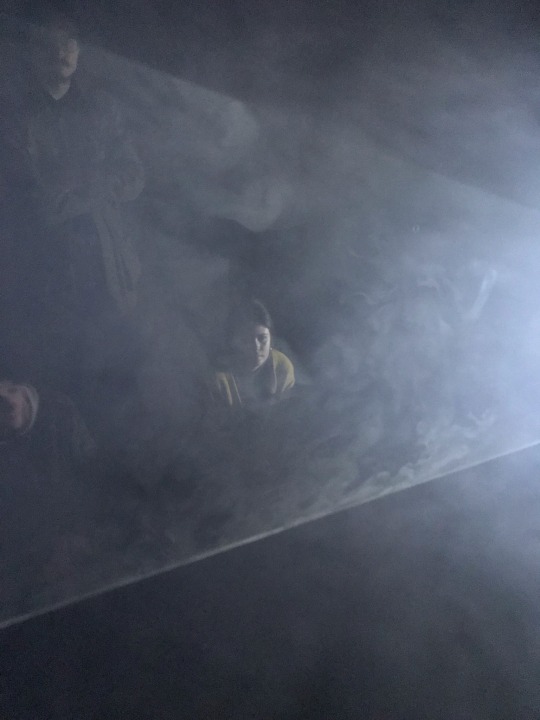

McCall moved to New York in 1973 where he embarked on a series of works dubbed ‘solid light.’ The groundbreaking Line Describing a Cone in 1973, was a first. The work was simple yet fascinating. The work was based on line drawing which shape the projection of light and makes a sculpture from a beam of light. Illusions of 3D shapes are created including ellipses, waves and flat panels. This work has been described as a blend of sculpting and cinema. Viewers of the art also become part of the art as their bodies block the light imaginatively.

The smoke is ghostly, it’s visible, but gives it an almost untouchable quality as it has a delicate ness to it- provokes a sense of wonder.

McCall- “in which I invited the audience to turn its back and face the projector in order to look at the three-dimensional form that existed between it and the screen.”

“You move into a dark space and what you see are planes of light moving across the space, intersecting with one another and you are surrounded by the work. You are also invited to enter it. These are sculptural forms, but they are made of something utterly immaterial. You can treat a plane of light as a wall if you like, but you also know that you can pass straight through it.”

April 30th 2018, Gabriel Florenz

Is your work also performative?

I think it is. When I made Line Describing a Cone I stumbled into all kinds of realms that I hadn’t really considered. I found that I was in sculptural space, which had to be taken into account, and I was also in a performance space, in that the spectator was negotiating the space in relation to the object that I’d made, while also negotiating the space in relation to the other visitors. Unwittingly, everyone becomes a performer for everyone else.

Are the works site-specific?

They are not; they are site-sensitive. There are certain basic requirements. The vertical works require a 30-foot room and a certain scale laterally; it needs to be dark; there needs to be a certain way for people to come in and out without disrupting the darkness; and there’s a light mist in the room that cannot be allowed to escape. If I’m invited to do an exhibition the first thing I do is look at the space to see how well it can be adapted to show these pre-existing works. There’s usually a lot of fine tuning and adjusting, with small changes that take place. Essentially, works precede an exhibition; they’re not made for it.

Do you consider the works to be sculptures, and if so why?

I do consider them to be sculptures because they are volumetric, three-dimensional objects in space and in order to comprehend them you have to walk around them. You have to move your own body in relation to these forms, which is a classic sculptural requirement.

Are they also a form of cinema?

Yes, they’re cinema because there is a structure that changes over time, which in the end is perhaps the most important element. If we showed these sculptural elements with no motion, with no change over time, you might think they are beautiful, but you wouldn’t stay for very long. The emotional charge, which people report receiving from being in these installations, comes from the paradox that we have something that appears not to move, but is moving very slowly and according to an identifiable logic, which you can follow. The two things together—sculpture and cinema—are the two elements that collaborate to produce the effects of the pieces.

How has technology impacted the way you’ve made these kinds of works over the past decades?

The big shift that has occurred in my lifetime is the shift from analog to digital. During the 1970s I used 16mm film, film cameras, film projectors and made things by hand. Fast forward 25 years, in the ‘80s and ‘90s we saw the big bang of the digital revolution, which—to come back to an earlier question—in retrospect the movement Expanded Cinema, with a capital E and capital C, was a controlled explosion, compared to the big bang of the digital revolution. During those two decades we saw the shift to the personal computer and the digital interface and gradually to projection itself changing profoundly. By about 2005—after I had been working again for a few years—I was completely comfortable with digital technology and programming. They provided opportunities for things that I could not have done before. For example, although I had drawn in my ‘70s’ notebooks the idea of a vertical work, it wasn’t until the invention of the digital projector that I could actually realize it. A film projector can’t really be turned 90 degrees from the ceiling without the reel falling off, but a digital projector is a grey box that can go any which way. So those kinds of opportunities were realizable for the first time.

Will the technology still be there to recreate them in the future?

That’s another great question. I think the answer is yes, but we live in a stage where we are constantly migrating our technology and our software. It produces different kinds of risks, which we learn to live with. The whole culture is predicated on the same risks. The art world is not a special case

https://buffalonews.com/2019/10/04/last-major-exhibition-before-albr

The viewer watches the film, by standing with his, or her, back towards what would normally be the screen, and looking along the beam towards the projector itself. The film begins as a coherent line of light, like a laser beam, and develops through the 30 minute duration into a complete, hollow cone of light.

The audience is expected to move up and down, in and out of the beam – this cannot be fully experienced by a stationary spectator. The shift of image as a function of shift of perspective is the operative principle of the film. External content is eliminated, and the entire film consists of the controlled line of light emanating from the projector; the act of appreciating the film-i.e., ‘the process of its realisation’-is the content.”

What is exhibited in Lismore Castle Arts, however, is Line Describing a Cone 2.0 (1973 – 2012). When McCall originally began showing these light sculptures in the 1970s, his venues were often grungy warehouse spaces, where people could (and did) smoke, and the air was thick with dust. This palpable atmosphere allowed the beam of projected light to manifest as a tangible thing, taking on weight, allowing him to cast lines and seemingly solid planes out of the air. However, as his work moved into more traditional gallery spaces, and the air became cleaner, the light works became less easy to realise. It was only in the 1990s, when he discovered hazer machines – a kind of dry ice emitter – that he could re-stage and revisit these works, this time using digital projectors rather than 16mm film. The haze machines lend the light works a distinctively aestheticized quality in comparison to (what I imagine to be) the rougher magic of the 1973 iteration. The controlled emission of oil- or water-based fluids imbue the projected light with a gorgeous, mobile surface quality, like flumes and eddies of watered silk. All of this imparts the work with a certain uncanny glamour; the impalpable is made apparently solid as air is given a weight and density, like an aesthetically seductive fog that haunts the room. The affective impact is beguiling and the performative aspect of the work is still very much in evidence – children dance in and out of the sheets of light, and people dip their fingers in the beams. Swell (2016) picks up where Line Describing a Cone left off in 1973, and one could argue that there is little development between the two works, bar the fact that digital technology allows him to achieve more intricate and complex progressions. One could also argue that the formal simplicity of Line Describing a Cone, its gradual evolution of the cone of light, familiar from cinema projection, has a satisfying conceptual neatness, whereas the later work is more elaborate, but re-treads much of the same ground. These works are utterly spectacular, with all the ramifications this word implies in terms of size, scale and visual pleasure – and they are achingly beautiful, aligning sheer sensuality with satisfying rigour – but the overwhelming sensory impact induces an almost narcotic effect, as borne out by the nearly hysterical, physical joy exhibited by the visiting children. A certain nagging, curmudgeonly voice whispers that this veers close to a mere entertainment, but it is a wholly transporting one at that- Sarah Kelleher, Enclave review 15, Summer 2017

The questions that led to Line Describing a Cone (1973) really had to do with whether it was possible to make a film that existed only at the moment of projection and so shared a common present tense with the audience. There was also the idea of the projection occupying the same physical space as the audience.

INTERVIEW

Line Describing a Cone emerged out of this train of thought, It was a cinematic problem that I was puzzling over. But having made it, it threw off a few surprises. One of those was the sculptural quality of the projection, and I began to investigate the different ways one might think about that. This led to three short “cone” films. One played with expanding and contracting the conical volume of the form while it simply hung in space; another, Partial Cone, made a series of scale-like sequences out of the way in which the light could be modulated to create different qualities of surface.

SC: Over the decades, do you recognise any shifts or seminal moments that highlight the evolution of your practice?

AM: I suppose the biggest shift was a negative one really, which was the 20 or 25 years where I had actually withdrawn from making art. One of the problems I was dealing with that led to this hiatus was that the work had just begun to be shown in museums, kunsthalls and biennials, where the conditions were very different from the ones that I made the works under. Originally, I made these works in lofts and I showed them in lofts – and as befits an ex-warehouse, they were full of dust. Also back then, many more people smoked than do now. In museum spaces, by contrast the air was very clean, there was no dust in the air, and certainly no cigarette smoking, and I suddenly had a visibility crisis. It wasn’t until the mid-nineties that the haze machine was invented, which decisively solved the visibility issue. Over the last fifteen years, I suppose the key thing for me would have been the discovery of verticality. I had actually imagined a vertical piece in one of my 1970s notebooks, but I was unable to make one until 2003. Of course, that was only possible because of the shift that had occurred in the 1980s and 1990s when analogue gave way to the digital. A 16mm film projector is gravity-bound. If you were to turn it through 90 degrees, in order to have it point from ceiling to floor, the reels would probably fall off; certainly it wouldn’t work. A digital projector is just a grey box and you can turn it to face any direction.

SC: How important is audience participation in your work?

AM: This is the hardest thing to articulate, since participation is important for all works of art. But perhaps there is a unique kind of engagement between a solid light work and the spectator. Part of it has to do with the fact that it isn’t really there in any normal sense, yet, standing or moving in the dark, the mind insists that the translucent membranes are walls and that the walls create spaces that the fully-conscious spectator can explore and occupy, and that despite the fact that the “solid light” forms seem sculptural, they are also slowly shifting in shape. The motion, slow as it is, I suspect is one of the keys to the pleasure that visitors articulate. It may also be connected to the contradiction between the impossible illusion of space on the one hand and the rational structure on the other.

- somethingcurated.com, Keshav Anand

1 note

·

View note