Text

Review of "Semi-Conducting: Rambles Through the Post-Cagean Thicket"

My review of Nic Collins' new book, Semi-Conducting (Bloomsbury, 2025) was accepted for online (~1200 words) and print (~700 words) publication with Leonardo.

I'll add links here when they are published.

0 notes

Text

Eastern Bloc March 20th

I was invited to participate in a panel on modular synthesis at Eastern Bloc as part of Martin Howse's visit.

The other participants are: Brian Mc Corkle, Erin Gee, Mimi Moussemousse, Philippe-Aubert Gauthier, Pipo Pierre-Louis.

I've been writing about Martin's work since I started working on my master's thesis eleven years ago. The latter contains an interview with him. I've also discussed his work in a couple of book chapters, including one which is part of the online content for the latest edition of the ur-text of diy synthesis, handmade electronic music. Martin remains one of my favorite artists and critical electronics users.

There will be concert after the roundtable. I think the event is a collaboration between Eric Mattson from Oral Bloc and André-Éric Letourneau from UQAM / Hexagram.

Talk at 5:30pm at Eastern Bloc on March 20th, 55 rue de Louvain Ouest.

0 notes

Text

Some Talks

I'm presenting at the Intelligent Instrument Lab's regular series on November 15th.

I'm presenting at the University of Birmingham's Music Department on December 4th.

Both events are free and the former may be open to the public online? not sure. I can find out if you want.

0 notes

Text

Postdoctoral fellowship Carleton/Ingenium

I've accepted a postdoctoral fellowship for a project on Hugh Le Caine which is sponsored by both the Ingenium Museums and Carleton University. I'll be working primarily with Dr. Tom Everrett to develop research and general public materials better situating the Electronic Sackbut and LeCaine in a wider history of synthesis in the 20th century.

0 notes

Text

Usually I would post these before the event but the room was so full clearly advertising more would have resulted in a fire hazard. thanks for coming out fam

1 note

·

View note

Text

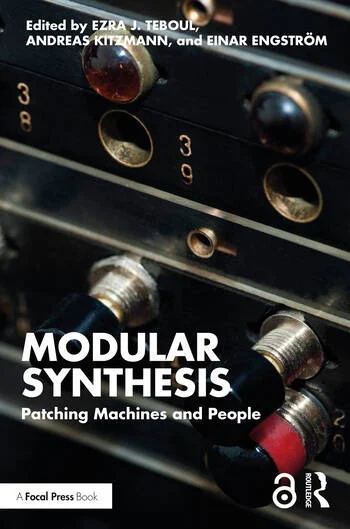

Book available for preorder

"Modular Synthesis: Patching Machines and People" is available for preorder. The release date is April 30th, and it will be available in pdf, paperback and hardback.

Introduction - Andreas Kitzmann and Einar Engström

Preface (All Patched Up: A Material and Discursive History of Modularity and Control Voltages) - Ezra J. Teboul

1. The Buchla Music Easel: From Cyberculture to Market Culture

Theodore Gordon

2. Modular Synthesizers as Conceptual Models

Jonathan De Souza

3. A Time-Warped Assemblage as a Musical Instrument: Flexibility and Constauration of Modular Synthesis in Willem Twee Studio 1

Hannah Bosma

4. Interview

Dani Dobkin

5. Gordon Mumma’s Sound-Modifier Console

Michael Johnsen

6. Artist Statement: Switchboard Modulars – Vacant Levels and Intercept Tones

Lori Napoleon

7. Eurorack to VCV Rack: Modular Synthesis as Compositional Performance

Justin Randell and Hillegonda C. Rietveld

8. Strange Play: Parametric Design and Modular Learning

Kurt Thumlert, Jason Nolan, Melanie McBride, and Heidi Chan

9. Grid Culture

Arseni Troitski and Eliot Bates

10. Modular Ecologies

Bana Haffar

11. Ourorack: Altered States of Consciousness and Auto-Experimentation with Electronic Sound

William J. Turkel

12. Patching Possibilities: Resisting Normative Logics in Modular Interfaces

Asha Tamirisa

13. Draft/Patch/Weave: Interfacing the Modular Synthesizer with the Floor Loom

Jacob Weinberg and Anna Bockrath

14. Composing Autonomy in Thresholds and Fragile States

David Dunn and David Kant

15. Virtual Materiality: Simulated Mediation in the Eurorack Synthesizer Format

Ryan Page

16. Interview: Designing Instruments as Designing Problems

Meng Qi

17. Interviews with Four Toronto-based Modular Designers

Heidi Chan

18. Interview

Dave Rossum

19. Interview

Paulo Santos

20. Interview

Corry Banks

21. Modular Synthesis in the Era of Control Societies

Sparkles Stanford

22. Randomness, Chaos, and Communication

Naomi Mitchell

23. Interview

Andrew Fitch

24. From "What If?" to "What Diff?" And Back Again

Michael Palumbo and Graham Wakefield

25. Interview: The Mycelia of Does-Nothing Objects

Brian Crabtree

1 note

·

View note

Text

Modular Synthesis: Patching Machines and People

I co-edited, with Andreas Kitzmann and Einar Engström, the first english language collection on modular synthesis.

It's a very partial look at a shapeshifting practice, at the meeting point of some of our most intangible mediums (electricity, sound) and most systematic, hegemonic systems (electronics, global industrial commodity chains) - but we wanted to offer a starting point.

I'll share the cover art (by Lori Napoleon, one of the chapter contributors) and the ToC when it's layed out.

1 note

·

View note

Text

When I was at Dartmouth we'd go to Jon Appleton's house for dinner about once a semester. He would give students stuff. He gave me pink moon boots and a collection of posters he'd kept. These are the posters.

0 notes

Text

Circuit music, circuit scores

In this [blog post that was supposed to be a book chapter] I discuss circuit music and what it says about notation and the place of electronic music instruments in a greater ecosystem of commodities. Developing Tara Rodgers' conclusion in her article, "Cultivating Activist Lives In Sound" I suggest that electronic components have an unrealized potential as a political medium within the context of music because they offer a) a glimpse at technological production after the profit motive and b) a grounds for technological minded composers to consider their role in the global of movement of commodities that makes their art possible. Such optimistic considerations are inevitably brought back to reality considering the the hegemonic ideologies within which this plays out - what is to be done?

Cardew's Stockhausen Serves Imperialism (1974) discusses the 1972 "International Symposium on the Problematic of Today’s Musical Notation" in Rome. Echoing Goifredo Petrassi, who according to Cardew stated that "notation was not in any way a real 'problem' facing composers today," (125) the British composer detailed his contribution to this "symposium on a nonexistent problem." (79).

Contrast this with the problem of notating electronic systems for design, testing, and manufacturing. Printed circuit boards, which today tend to be designed digitally, were a 60.2 billion dollar market globally in 2014. Microelectronics, which also rely on a system of notation for their design, since semiconductors must be deposited in precise arrangements relative to each other, were one order of magnitude higher at 555.9 billion dollars in global sales in 2021.

This glut of manufacturing of electronics has been an ongoing phenomena since the second world war (Gabrys 2013). With the Cold War compounding this dramatically (Wolfe 2012), the surplus of unused or discarded military equipment was so common and cheap in north america that composers such as David Tudor and his collaborators in the Composers Inside Electronics group were able to explore what Nicolas Collins calls the "music implicit in technology" (Collins 2007, 46). This form of composing, which I called in another draft circuit music, is concerned expressly with the arrangement of electronic components and systems for music and performance, rather than the more traditional arrangement of sounds or instructions for sound-making by instrumentalists. In terms of notation, circuit music is the set of musical works that are discussed, written and conceived of in the idiom of electronics, rather than music: circuit schematics and diagrams, first, and, in a related fashion but with too much at hand to be discussed in detail here, computer programs. I'll call these forms of notated circuit musics technical abstractions below.

In that sense circuit music is at an odd crossroad. On the one hand, its use of notation is about as real a problem as graphic notation was to avant-garde european composers in the 1970's, as assessed by Cardew and Petrassi: it does not matter much in terms of hegemony (cultural or financial) whether or not composers use the european symbol for resistor, the american symbol, or make up their own for the various abstractions used in and for their circuit-compositions. On the other, electronics do use notated and notating techniques (in the form of microchips and circuit schematics augmented with the occasional computer program) that are about as real as things can get in our contemporary context. Electronics mediate the majority of musicking experiences, at least in the west (Devine 2019).

In 1990 a MoMA exhibit titled "Information Art" (funded by Intel) offered a book of essays in which one Cara McCarty writes in passing that "microelectronics represent the essence of mass production." [McCarty 1990, 5] If circuit music is a sounding of the music implicit in technology, and that technology is mass produced, can the genre (and live electronic music more generally) be read as a sonified form of mass production? In other words, is circuit music meaningfully understood as an attempt to make sense of mass production through a making-music of some of its most ubiquitous rejects? If it is then it is not particularly surprising to see at least one iteration of circuit music emerge in New York City, next to Bell Labs and R.C.A., by touring musicians who would also come close with other initiators of electronic music generally (Buchla, Moog, the Columbia-Princeton Electronic Music Center). There were enough cheap components, people with free time, and a culture of diy electronic sound for it to happen eventually (Haring 2007). And yet circuit music tends to be an oddity, generally called "live electronic music" to bundle it with some early forms of computer music (such as that of the Hub and the later League of Automatic Musicians), and placed under the "pioneering" work of David Tudor - on whom the first book has only just been published (Nakai 2020). Cultural contextualizations of the practice are scarce, and the present publication is, as far as I know, the first one to suggest that not only might circuit music be an attempt to make sense of the technological overproduction of the west during the 20th century (if musicians weren't going to make music out of all this stuff, then what was it all for?) but also that it might in sense represent one of the most unadulterated sonifications of that overproduction. Every squelch, every beep, every bloop heard in what I'm calling circuit music is more than an experiment by Tudor or Mumma or Collins or DeMarinis, etc - it's a scream compounding the labor and materials involved in making those components available to those people in their respective time-places. Rephrasing an earlier question: in what sense is circuit music simply the music of western technoscience's hegemony?

Not in every sense: circuits were used creatively, even subversively by artists and activists throughout the 20th century. Even Composers Inside Electronics, who never exactly wore their politics on their sleeves, wrote discreetly and sporadically about the social hierarchies, folk crafting histories and utopias they were perhaps hinting at through and with their circuits and performances (Mumma 1974, DeMarinis cited in Teboul 2020, add p. range). These counter-scriptings of technology (Akrich 1992) have only accelerated today, generally much beyond music (Dunbar-Hester 2014 and 2020, Flood 2020, Striegl 2020), if only because there are more computers to hack and more people to hack them. There, electronic music generally and circuit music specifically are in a unique situation to respond to Tara Rodgers' call for cultivating activist lives in sound (2015), because of the massive production and consumption chains required to make these practices simply possible, let alone good in whatever aesthetic sense you might be interested in. Indeed, under the conflict of notation at the heart of electronic / music, lies the friction between a deeply experimental and open ended practice, where musical forms are generally remediated to quaint side effects through primarily cultural means, and a deeply formal tradition of electronics design and small scale assembly, itself undergirded by perhaps the largest, most active and most codependent industrial behemoth ever conceived and executed: the global electronics industry. The latter [silicon earth, planetary mine, etc] is so dependent on both a large variety of manufacturing techniques, intermediate products and externalized manufacturing costs that it would hardly be recognizable or exist at all if this supply chain were to break down or our consumption drastically change: the former is visible in the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on computer parts availability, even if the latter seems mostly to remain a luddite pipe dream at the moment. Scholars like Benjamin Bratton also rightfully point out that the response to the climate crisis (2016, add page range)- in no small part caused by the electronics industry and its gargantuan energy, mineral and human needs - is likely to have more electronics touted as part of its own solution: more smart meters, more supply chain tracking, more computers for every vehicle as we transition to electric cars instead of public transit, and so on.

In the middle of this shitstorm the scale and affect of electronic music and circuit music seems fairly quaint. In terms of volume it's a fraction of say, the computer market (add reference). But this is where what I identified in past writing (Teboul 2018) as diy electronic music's post-optimality feels relevant. Post-optimality names the productive inefficiencies, the inspiring user-unfriendliness, the various fetishizations and romanticizations - in other words, the reasons why a small subset of people seem dedicated to vacuum tube amps and analog synthesizers regardless of their cost, weight, and difficulty of maintenance. This is to the point of restarting the fabrication of obsolete microchips (add ref) or maintain entire soviet-era factories (add ref), even if at no scale comparable to the rest of the electronics industry. Either way it compounds interestingly with its place between electronics and music: indeed circuit music is so explicitly post-optimal that it is rarely enacted with financial expectations other than loss. It would be interesting to do a survey of musicians who hope to recoup expenses on their gear through their artwork versus how many eventually do, and compare that with the equivalent statistics for circuit musicians widely construed. The comparison is flawed, as some electronic artists did eventually turn some form of social capital into gainful employment (I am thinking specifically of all the ex-composers inside electronics working at universities). But the way that circuit musicians, as documented in my decade of ethnographic fieldwork and participant-observation studies (add refs) reinvent electronics for variously esoteric applications meaningful primarily for themselves, suggests that circuit music (and its various forms of technical abstractions which enable, encode and communicate that music) can offer - like other creative applications of technology - a glimpse at what we can do with the aftermath of capitalism after the abolition of the profit motive.

In previous writing (Teboul 2020, add page range) I'd offered a distinction between canonical technical devices, those which are documented in engineering textbooks and taught in accreditation-seeking engineering curricula, from vernacular systems, those developed in more ad-hoc conditions by people who may be aware of canonical devices or not, but with very little intent on being documented back into what Marx called "general intellect," that is, the collective knowledge reasonably available to members of society [add ref]. Part of my work studying circuit music has been identifying the precise paths taken by artists working from canonical systems, or at least standardized components, and literally inventing new systems through guesswork, experimentation, or study. In other words, part of my work is concerned with reverse engineering vernacular systems to better identify the extent to which circuit music is itself a form of engineering and give, as possible, credit to all the work done and the creativity displayed along the way. What emerges from this ongoing project is that circuit musicians are one example (possibly amongst many) of electronic arts within which the privilege of access to cheap electronic components and computing environments- whether acknowledged and investigated or (more commonly) not - of what happens when humans get to fuck around with stuff feeling like they don't need to show anything for it, however artificial that condition may be. Of course there are plenty of electronic artists who develop their practice fully aware of its complicated connection to capitalism and extractivism, with an increasing number of contemporary artists (myself included) for whom that is explicitly the focus and goal. But there is the suspended disbelief inherited from experimental music: we try to wire these components in new ways without the assurance of success not because we want to mass produce anything, but just because we were curious to try it and see if it behaves as expected. This is not particularly original - similar arguments have been made of punk or improvised music and their social effects, for example - but I don't think it's a coincidence circuit music emerged roughly at the same time.

So of course circuit music as a glimpse of technology after the profit motive is blatantly and naively optimistic. Punk didn't exactly change the world, circuit music certainly didn't either. Lauren Flood's discussion of musical hacking in nyc and berlin (Flood 2020) seems to work along parallel lines, identifying that people feel like they're doing something potentially utopian and radical, but also acknowledging that in-depth investigation of the means and effects of these activities tend to temper most of their reach as localized and perceptual, if not imaginary.

This is - to me - exactly the point. There is a very straightforward material and didactic effect that circuit music has on the practitioner, and, with some preparation, their audiences: a realization of the connected nature of the electronic commodities, their production and consumption chains, the materials and labor that make them possible. If live electronic music is the music implicit in mass production, then every sounding is an opportunity to learn about the forces responsible for environmental and human disasters. In that sense circuit music can serve as one of the many cultural spaces within which artists can develop the tacit knowledge of electronic commodities chains we will need to begin to think of the possibility of an ethical electronic music, one which does not rely on exploiting semiconductor factory workers in southeast Asia, or more fossil fuels and plastics to make electronic music possible. Between the rigidity of semiconductor dyes, perfectly notated and printed designs from above, and improvised circuit board-compositions with their occasional little embedded programs, is the field within which we decide what systems of power and notation we are willing to grapple with and which we choose to abandon as irredeemably unsustainable.

Bibliography:

Akrich, Madeleine. 1992. “The De-Scription of Technical Objects.” In Shaping Technology/Building Society: Studies in Sociotechnical Change, edited by Wiebe Bijker and John Law, 205–24. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Bratton, Benjamin H. 2016. The Stack: On Software and Sovereignty. MIT press.

Cardew, Cornelius. 1974. Stockhausen Serves Imperialism, and Other Articles: With Commentary and Notes. Latimer New Dimensions.

Collins, Nicolas. 2007. “Live Electronic Music.” In The Cambridge Companion To Electronic Music, 38–54. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Devine, Kyle. 2019. Decomposed: The Political Ecology of Music. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Dunbar-Hester, Christina. 2014. Low Power to the People: Pirates, Protest, and Politics in FM Radio Activism. Cambridge: MIT Press.

———. 2020. Hacking Diversity: The Politics of Inclusion in Open Technology Cultures. Princeton Studies in Culture and Technology. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Flood, Lauren. 2020. “The Sounds of Zombie Media.” In Audible Infrastructures, 229–53. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gabrys, Jennifer. 2011. Digital Rubbish: A Natural History of Electronics. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Haring, Kristen. 2007. Ham Radio’s Technical Culture. Cambridge: MIT Press.

High, Kathy, Sherry Miller Hocking, and Mona Jimenez, eds. 2014. The Emergence of Video Processing Tools. Bristol: Intellect Books.

Jones-Imhotep, Edward. 2008. “Icons and Electronics.” Historical Studies in the Natural Sciences 38 (3): 405–50.

Kharpal, Arjun. 2022. “Global Semiconductor Sales Top Half a Trillion Dollars for First Time as Chip Production Gets Boost.” CNBC. 2022. https://www.cnbc.com/2022/02/15/global-chip-sales-in-2021-top-half-a-trillion-dollars-for-first-time.html.

McCarty, Cara. 1990. Information Art: Diagramming Microchips. New York: Harry N. Abrams with the Museum of Modern Art.

Mumma, Gordon. 1974. “Witchcraft, Cybersonics, Folkloric Virtuosity.” In Darmstadter Beitrage Zur Neue Musik, Ferienkurse ’74, 14:71–77. Mainz: Musikverlag Schott.

Nakai, You. 2021. Reminded by the Instruments: David Tudor’s Music. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Rodgers, Tara. 2015. “Cultivating Activist Lives in Sound.” Leonardo Music Journal 25: 79–83.

Striegl, Libi Rose. 2020. “Voluntary De-Convenience: A Workshop Kit.” Doctoral Dissertation, Boulder: University of Colorado, Boulder.

Teboul, Ezra J. 2018. “Electronic Music Hardware and Open Design Methodologies for Post-Optimal Objects.” In Making Things and Drawing Boundaries: Experiments in the Digital Humanities, edited by Jentery Sayers, 177–84. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

———. 2020. “A Method for the Analysis of Handmade Electronic Music as the Basis of New Works.” Doctoral Dissertation, Troy, NY: Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute.

Wolfe, Audra J. 2012. Competing with the Soviets: Science, Technology, and the State in Cold War America. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press.

“World PCB Production in 2014 Estimated at $60.2B.” 2015. 2015. https://www.iconnect007.com/index.php/article/92973/world-pcb-production-in-2014-estimated-at-602b/92976/?skin=pcb.

0 notes

Text

“Beyond Circuits” - Columbia University Computer Music Center project (winter 2022)

In the winter of 2022 I received funding from the Institut Francais through the FACE foundation’s Etants Donnes program to undertake an artistic project at the Columbia University Computer Music Center, under the supervision of Seth Cluett (now director of the center).

There I focused on two archival collections: the paper records for the CMC, now housed within the music library in Dodge Hall (after years in Prentis Hall), and still under review for cataloguing; and the audio electronic equipment collection, which is split between various offices, studios, and the storage closets of the CMC at Prentis on 125th st.

I also undertook some interviews with various members of the technical staff and residents of the center from over the years. Virgil deCarvalho, Brad Garton, Peter Mauzey, Alice Shields, Pril Smiley, Luke DuBois and Seth Cluett were particularly generous with their time here (thank you!).

The goal of the project was to understand the extent to which the material history of the center had been documented. My perspective as a historian of music and sound technology, as well as an artist, had made it clear to me that although scholarship regarding the artists visiting the center offered significant detail regarding not only their musical accomplishments and innovations, but also - it must be said - the relatively strong diversity of nationalities and genders compared to the rest of academic electronic and computer music over the years (see for example the recent “Unsung Stories” events - https://www.unsungstoriescmc.com/), an understanding of the material and technical labor that made the center possible over the years wasn’t quite as available.

The center’s paper archives consists of 125 linear feet of materials, mostly paper-based, and with a significant amount of documentation of their everyday operations until these receipts and memos became primarily electronic in the 90′s and 00′s. In that sense, the CMC’s paper archives are probably one of the most detailed historical records of institutional electronic music history’s, and by extension, one of the best location to begin developing systematic methods and tactics of understanding the practice’s basis in the use of electronic components and technical labor. Building on my doctoral work, I wanted to consider the way that the technicians and the musicians and composers interacted through the medium of memos, notes, discussions and technical objects. This felt particularly worth investigating because the center’s history starts after the invention of semiconductors, but before the availability of mass-produced audio equipment: one of my underlying motivations was therefore to see if the equipment that the center’s staff literally had to invent prefigured the functionality of commercial equipment that became standard later, or if it represented a more unique, unexplored path.

My initial plan was to review the equipment and archives and do interviews in my first two months in new york, and to spend the following two re-building hardware that stood out as interesting and developing accompanying AR material for people to explore the equipment’s history and quirks virtually in addition to electro-acoustically. Things took a different turn when the paper archive proved to be quite difficult to consult: the music library staff (primarily Nick Patteson, bless your soul) was committed to giving me access, but COVID regulations and the unprocessed nature of the collection meant that I had to consult things under his supervision, a few boxes at a time. In addition, some of the boxes were in Dodge, while others were in the political science and humanities library. In addition, there turned out to be a wealth of materials. I ended up taking over 8000 pictures of textual documents, including hundreds of receipts, personal correspondance, and a selection of technical specfications or manuals for some rare, unique, or purpose-built equipment, but this took roughly two months, during which I also took a few hundred pictures of the equipment itself and their internal circuitry, and undertook a few interviews / contacted the members of the staff that felt relevant over email. I am happy to coordinate with researchers and Seth to share a copy of my pictures for relevant projects - just reach out to me or Seth if you’re interested.

https://twitter.com/RedThunderAudio/status/1498856036836511744 has pictures of the main RCA mark II schematics.

https://twitter.com/RedThunderAudio/status/1499152944964554753 this thread has image of various Buchla receipts and setups.

In that time it became clear that the project I had initially sketched out would be difficult to fit within a 3 year postdoc, let alone a 4 month short residency, and I decided to focus on documentation, for less devices than I’d originally planned. Based on discussions with Kurt Werner and Seth Cluett, the chosen circuits were the Albis parametric EQ and the Mark II’s passive sound effects filter units. The AR tools I’d initially considered felt less promising than developing pure data objects / the framework for emulating future circuits. This became the object of a DAFX paper, primarily written by Kurt, with technical assistance from Emma Azelborn, historical and epistemological context from me, and contributions from Seth.

The paper is available here: https://href.li/?https://dafx2020.mdw.ac.at/proceedings/papers/DAFx2020in22_paper_39.pdf

The archive for Kurt’s technical work, an example patch, and the object is here: https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1WaZTkHtqc8_WENXYu_pA7ZBCPoG_jdri?usp=share_link

PLEASE NOTE: the object is being shared under a non-commercial, attribution, share-alike license (CC-BY-NC-SA), with the approval of the CMC at Columbia. If you have any licensing questions please email me or Seth Cluett, director of the CMC.

This includes the FAUST code that Kurt developed to make the object - more details are available in section 5 of the DAFX paper. The general approach and objectives were also discussed in more detail in an AES panel with Kurt, Seth, and others: https://aesfallconvention2022.sched.com/event/1Ay7v/software-modeling-of-historical-analog-instrument-circuits

I also collaborated with Mark Milanovich from the MEMS project to document some of the very early Buchla modules present at the CMC, including the infamous “red” 158 module (for more about MEMS, see https://www.memsproject.info/). Mark developed full traces for the modules we looked at, helping document the various iterations of Don’s circuits.

My perspective on the Mark II synthesizer and the discourse surrounding it before, during and after its main period of use will be the focus of two talks I’m presenting at 4S in December 2022 - I’ve copied the abstract at the end of this post. As will be clear to people reading the abstracts, one of the things that became clearest to me in reviewing these materials and learning about the center is how everything - from the interaction between technicians, composers, and staff, to where the materials were coming from and who was assembling them prior to their arrival at the center - fits within a greater history of the 20th century’s western industrial project. The music produced at the center- in many ways what’s already been the most discussed- is of course relevant to scholars of the century’s avant-garde, and even to amateurs of electronic music history in general (since it seems so many of the circuits developed in house were basically predecessors of what became eventually commercially available), but the CMC also has wider relevance as an edge-case for how cold war politics instrumentalized institutions in making sense of their arms races.

Some expected outcomes of this initial work:

I hope to write a more general article-length discussion of the topic in the coming months - this has been slowed down primarily by my commitments to completing the editing work on a collection on modular synthesis for Routledge (where I’ll also discuss the Mark II and related systems in the introduction), which is due early 2023.

In addition, I plan on attempting to develop a pure data object emulating the Albis, based on Kurt’s example for the SEF and our notes on the topic. Then, I also have been experimenting with implementing some of the Mark II patches I found detailed in the archive as pure data patches.

Finally, I have also been working on music with the pure data SEF object, as well as various ideas adapted from past documentation available in the archive. I hope to release these as part of a brief text I’m putting together discussing the information that was not available in the archive regarding the origin of the materials which made the CMC possible - even though there is a first layer of receipts for a significant number of electronic and mechanical parts, the idea of tracing the mineral origin of the CMC’s electronics is mostly aspirational.

Frankly, there are at least a dozen articles and a couple of books which could and should be written about these two collections. My main roadblock for working on these is funding availability. Feel free to reach out to me if you are interested in collaborating or supporting this work in some way.

I’ll post here as these follow-up projects get implemented.

-------------

https://www.4sonline.org/meeting/final-program-4s-esocite-2022/

panel 10: Arts, cultures, cultural industries and heritages: shifting objects for STS

paper title: The noise/music at the edge of western extractivism

abstract: Drawing from a residency at the Columbia University Computer Music Center archive - probably one of the longest and best documented electronic music centers in the world - I offer an analysis of the first modular electronic music synthesizer, the RCA Mark II, installed in 1957, as a technoscientific fetish. Weighing at two tons and using a few hundred vacuum tubes, this analysis investigates what exactly the system represented to the wider project of midcentury american technoscience. Building on prior research by Trevor Pinch, Nelly Oudshoorn, Audra Wolfe and Wiebe Bijker, as well as the anthropological theory of art of Alfred Gell, I discuss the system's circuits as the apex of some its eras large sociotechnical systems, namely, those underlying the electronics commodity supply and consumption chain with RCA at their core. RCA - the state-sponsored patent monopoly turned giant of the war efforts, was at the end of the 50's in a hegemonic position which allowed it to extract value from its IP and invest in research projects with unclear or questionable financial objectives, such as the Marks I and II systems. I suggest that rarely are the political underpinnings of the american technological machine as clear as in their superfluous production. The Mark II acts as, in Gell's usage of the term, a fetish for the maximalist extractivism that has characterized the west since. The noise-music it has produced, and the cultural imaginary that surrounds it, served to effectively attempt and literally make-musical the largely accelerationist project of 20th century industrialism.

panel 105. Repair and Maintenance of Media Technologies

paper title: Reverse engineering reverse engineering: an ethics of media arts maintenance and conservation

abstract: Drawing from a decade as a media artist, audio electronics repair engineer, and scholar, this presentation highlights both the potential and epistemological blind spots of reverse engineering as a research method in the maintenance and conversation of media art works and technologies. Reverse engineering, from a material-epistemological standpoint, is explicitly concerned with not needing consent or input from the original authors to recover information embedded in a material artifact; the potential for non-consensual information extractivism. Audio systems - rarely critical to the operation of most infrastructures other than cultural - offer a relatively low-stake environment within which to gain experiential understanding of the underlying ethics, highlighting both the need to reverse engineer and its pitfalls. Extending the work done on engineering in science and technology studies, I reverse engineer the materio-epistemic engine that is reverse engineering using case studies in the history of the media arts. I draw primarily from my current project of the Mark II synthesizer, one of the first institutional modular sound synthesis systems built by RCA in 1957 and installed at Columbia's electronic music center in harlem. I suggest that reverse engineering is both made possible and necessary by the increasing circuit design complexity afforded by the mathematical tools developed by engineers to predict the behavior of real-life components and circuit topologies, a complexity which is not addressed by media archaeology.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Dafx Paper link

Werner, Kurt James, Ezra J. Teboul, Seth Allen Cluett, and Emma Azelborn. 2022. “Modelling and Extending the RCA Mark II Synthesizer.” In Proceedings of the Digital Audio Effects (DAFX) Conference. Vienna, Austria. https://dafx2020.mdw.ac.at/proceedings/papers/DAFx2020in22_paper_39.pdf.

0 notes

Text

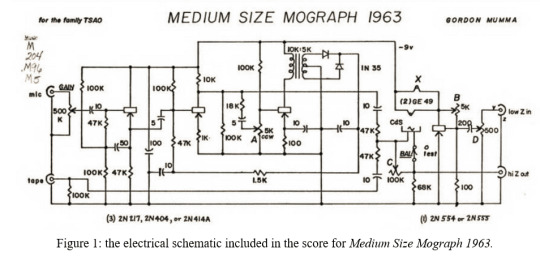

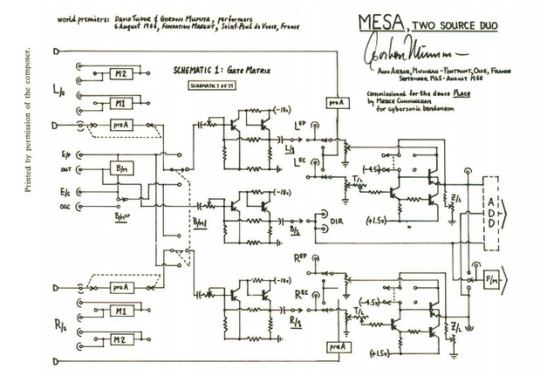

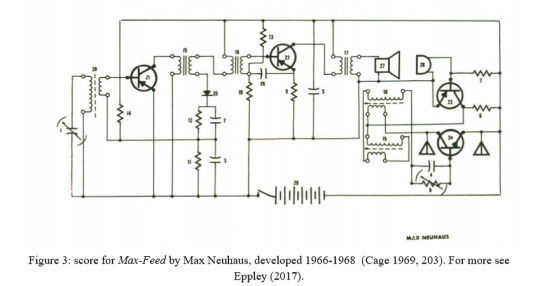

A history of circuit music / schematic as score in quotes and circuit diagrams:

"TRADITIONAL notation has been abandoned in so much of the last decade's music that players are no longer shocked by the prospect of tackling a new set of rules and symbols every time they approach a new composition." (Behrman 1965, 58)

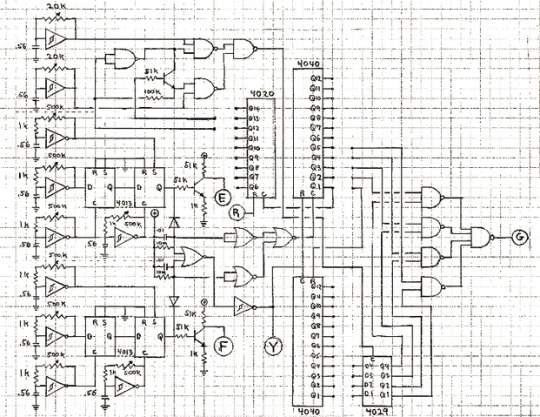

Figure 2: schematic for Mesa by Gordon Mumma, dated 1965-1966, Ann Arbor (Cage 1969, 199). For more, see Goldman (2020). Note this is only one of eleven schematics required to build the circuit-composition.

“My electronic music equipment is designed to be part of my process of composing music. I am like any composer who builds his own instruments, though most of my “instruments'' are inseparable from the compositions themselves. My “end-product” is more than a package of electronic hardware: it is a musical performance for a live audience. On occasion my technical concerns may be differently oriented from those of the usual electronic engineer. Nonetheless, we are concerned with common ground: the applications of electronic technology, in my case to music.” (Mumma 1967, edited 2015, p.43)

“My engineering decisions concerning electronic procedures, circuitry, and configurations are strongly influenced by the requirements of music making. Thus my designing and building of circuits is “composing” that employs electronic technology in the achievement of my musical art. Though I may describe my use of certain electronic procedures because they result in certain sounds, these procedures were not always chosen on a cause-and-effect basis. Sometimes I am looking for a certain kind of sound modification, and I work on various circuits until I have achieved that result. Other times in casually experimenting with different configurations of circuits I may chance upon some novel sound effect that becomes the germinating idea for a piece of music.” (44)

“Independent circuits developed by individual artists represent further development in this genre. Mumma broke ground in this area with his Hornpipe (1967), Mesa (1969) and other circuits. The unique aspect of this type of work lay in the circuit's de facto equivalence to a score.” (Gersham-Lancaster, 1998, 40)

“Another strong concept in Gordon's work is process. Perhaps electronics, which are very process-oriented, have influenced his musical thinking, but perhaps again his thinking, being already process-oriented, had an innate affinity to the concepts of electronic processes. Even his earliest works are process oriented. [...] The electronic network [used in Hornpipe] shapes the process by its own limitations and its own particular dimensions. The circuit is the process is the score is the work itself. The performance is an exploration of what that particular process allows.” (Payne 2000 (written 1976-82), 109-110)

personal communication with Payne, 7/30/2021: "I think that I originally finished the article on Gordon in 1976. I seem to remember that Mimi Johnson later asked for revisions and updates from everyone involved, which is why works dating as late as 1982 are included in my article."

“Due to the evanescent nature of the signal present at the random inputs, the melodic patterns generated by the Pygmy Gamelan are perpetually changing but bound to the metric and modal constraints designed into each unit. In this sense, the electronic circuit itself functions as the score, as well as the instrument and the performer.” ( DeMarinis 1973, 47)

“That was a piece in which that is the score—that is, the instrument, that is that object that does that thing. I was somewhat of a zealot about that idea, of not wanting to make instruments, not wanting to make general-purpose instruments. I thought of myself as thinking much more in the culture of art, making objects that were pieces, sometimes requiring performances, sometimes not, sometimes standing alone.” (DeMarinis in Ouzounian 2010, 12)

“ANDS combines basic concepts of musical instrument, structure, and form into one set of circuits. The structure of any particular performance is determined by coordinations between the players and the circuit. The form of the piece results from relationships that develop among the players in performance. The primary score is the circuit itself. Awareness of the form is necessary for performance. This awareness can best be attained through some direct experience with the instrument and the structure. Someone who understands the circuit-as-score should design rehearsal instructions that will expose the players to the factors that shape the piece.” (Collins 1979, 40)

Figure 4: one of the three circuit schematics provided in the score and instructions for ANDS by Nicolas Collins (1979, 40).

“The idea certainly did not originate with me, I was parroting the philosophy a lot of us were following at the time. Composers Inside Electronics started at Chocorua, NH in the summer of 1973. And that in turn built on a notion that Tudor had had for some years, shared with Mumma for sure and likely Behrman (Mumma pre-dates Tudor on several key electronic developments) “ (personal communication with Collins, 12/10/2019)

Collins 2012 p. 26: "In an outtake from his 1976 interview with Robert Ashley for Ashley's Music With Roots in the Aether, Alvin Lucier justified his lack of interest in the hardware of electronic music with the statement, 'Sound is three-dimensional, but circuits are flat.'"

"In Hornpipe and Runthrough, there were no scores to follow; the scores were inherent in the circuitry - that was a new idea for me." (Lucier 1998, 6)

“The circuit—whether built from scratch, a customized commercial device, or store-bought and scrutinized to death—became the score.” (Collins 2004, 1)

"With an open-form score that encouraged experimentation in the design of sound generators and resonated objects, this work served as a creative catalyst for the workshop participants and, later, other young composers who were drawn to Tudor by word-of-mouth." (Collins 2006, 40)

"Immersed in a musical ethos that valued chance, they were highly receptive to accidental discoveries—in the pursuit of the “score within the circuit,” they relished wandering down side paths, rather than race-walking toward a predetermined goal." (Collins 2006, 91).

“Composers traditionally use scores to convey required instructions that the performer must follow to reproduce a series of sound events, or a composition which is executed using a series of commands. Even in the case of semi-improvised graphic scores, like those of Stockhausen, the performer is asked to make various choices within a parameter set. However, when the electronic circuit is transformed into a score, or installed as an auto-generative system, the musical hierarchies of composer, performer, and listener are also transformed, conflating into a facilitator or receptor of signal flow and modulation”. (Eppley and Hart 2016)

bibliography and related texts:

Ashley, Robert. 2000. Music with Roots in the Aether: Interviews with and Essays About Seven American Composers. Köln: MusikTexte.

Behrman, David. 1965. “What Indeterminate Notation Determines.” Perspectives of New Music 3 (2): 58–73.

Beirer, Ingrid, ed. 2011. Paul DeMarinis: Buried In Noise. Heidelberg: Kehrer Verlag.

Blasser, Peter. 2015. “Stores at the Mall.” Master’s Thesis, Wesleyan University.

Braun, Hans-Joachim, ed. 2000. Music and Technology in the Twentieth Century. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press.

Cage, John. 1969. Notations. New York: Something Else Press.

Collins, Nicolas. 1979. “Three Pieces.” Master’s Thesis, Middletown, Connecticut: Wesleyan University. https://www.nicolascollins.com/texts/Collins_MA_thesis.pdf.

———. 2006. Handmade Electronic Music: The Art of Hardware Hacking. New York: Routledge.

———. 2007. “Live Electronic Music.” In The Cambridge Companion To Electronic Music, 38–54. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

———. 2012. “Semiconducting: Making Music After the Transistor.” Seminário Música Ciência Tecnologia 1 (4).

DeMarinis, Paul. 1975. “Pygmy Gamelan.” Asterisk: A Journal of New Music 1 (2): 46–48.

Eppley, Charles. 2016. “Circuit Scores: An Interview with Liz Phillips.” Avant. April 8, 2016. https://web.archive.org/web/20161025062750/http://avant.org/artifact/liz-phillips/.

———. 2017. “Soundsites: Max Neuhaus, Site-Specificity, and the Materiality of Sound as Place.” PhD Thesis, The Graduate School, Stony Brook University: Stony Brook, NY.

Eppley, Charles, and Sam Hart. 2016. “Circuit Scores: Electronics After David Tudor.” Avant (blog). 2016. http://avant.org/event/circuit-scores/.

Getreau, Florence, ed. 2018. Instruments Électriques, Électroniques Et Virtuels. Musique Images Instruments, n. 17. Paris: CNRS Éditions.

Getty Research Institute. 2001. “The Art of David Tudor-Symposium.” Past Events. May 17, 2001. https://www.getty.edu/research/exhibitions_events/events/david_tudor_symposium/.

Goldman, Jonathan, Francis Lecavalier, and Ofer Pelz. 2020. “La Migration Numérique D’une Oeuvre Pionnière Avec Live Electronics. Mesa (1966) De Gordon Mumma.” Revue musicale OICRM 6 (2): 1–24. https://doi.org/10.7202/1068383ar.

Gresham-Lancaster, Scot. 1998. “The Aesthetics and History of the Hub: The Effects of Changing Technology on Network Computer Music.” Leonardo Music Journal 8 (1): 39–44.

Hartman, Lindsey Elizabeth. 2019. “DIY in Early Live Electroacoustic Music: John Cage, Gordon Mumma, David Tudor, and the Migration of Live Electronics from the Studio to Performance.” Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University.

Holzer, Derek. 2010a. “Schematic as Score: Uses and Abuses of the (in) Deterministic Possibilities of Sound Technology.” In Vague Terrain 19, edited by Derek Holzer. https://web.archive.org/web/20131124040627/http://vagueterrain.net/journal19.

———, ed. 2010b. Vague Terrain 19: Schematic as Score. https://web.archive.org/web/20131124040627/http://vagueterrain.net/journal19.

Lucier, Alvin. 1998. “Origins of a Form: Acoustical Exploration, Science and Incessancy.” Leonardo Music Journal 8: 5–11.

Mumma, Gordon. Medium Size Mograph 1963: For Cybersonically Modified Piano with Two Pianists. 1969. Don Mills, Ont.: BMI Canada.

———. 1967a. “Creative Aspects of Live-Performance Electronic Music Technology.” In Audio Engineering Society Convention 33. Audio Engineering Society.

———. 1967b. Medium Size Mograph 1962. Don Mills, Ont.: BMI Canada.

———. 1974. “Witchcraft, Cybersonics, Folkloric Virtuosity.” In Darmstädter Beitrage Zur Neue Musik, Ferienkurse ’74, 14:71–77. Mainz: Musikverlag Schott.

Mumma, Gordon, and Michelle Fillion. 2015. Cybersonic Arts: Adventures in American New Music. Music in American Life. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Nakai, You. 2021. Reminded by the Instruments: David Tudor’s Music. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Nakai, You, and Michael Johnsen. 2020. “The Mumma-Tudor Ring Modulator.” In .

Payne, Maggi. 2000. “The System Is the Composition Itself.” In Music with Roots in the Aether: Interviews with and Essays About Seven American Composers, 109–26. Koln: MusikTexte.

Pinch, Trevor, and Frank Trocco. 2004. Analog Days: The Invention and Impact of the Moog Synthesizer. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Turner, Fred. 2010. “The Pygmy Gamelan as Technology of Consciousness.” In Paul DeMarinis: Buried in Noise, 22–31. Heidelberg: Kehrer Verlag.

Weium, Frode, and Tim Boon. 2013. Material Culture and Electronic Sound. Smithsonian Institution Scholarly Press.

0 notes

Text

Paper accepted to DAFX 2022

My paper with Kurt Werner, Seth Cluett and Emma Azelborn, “ Modeling and Extending the RCA Mark II Sound Effects Filter“ was accepted to the proceedings of the dafx 2022 conference.

We’ll be implementing reviewers suggestions until June and I’ll link to the paper here once it’s published as part of the proceedings!

0 notes

Text

Review of “Stereophonica” published

My third book review, for Gascia Ouzounian’s fantastic work on space and listening, is online at the Journal of Sound Studies.

https://www.researchcatalogue.net/view/558982/1625023

0 notes

Text

Review of “Reminded By The Instruments”published

My second book review, of You Nakai’s work on David Tudor “Reminded By The Instruments,” was published in the computer music journal by MIT Press. There were some issues in the review process and although I stand by the version that made it to print (https://direct.mit.edu/comj/article-abstract/45/1/85/110386/You-Nakai-Reminded-by-the-Instruments) I recommend reading this draft:

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1ULDedp-3RyKDcFMiFilu75Mz9oVShVgE/view?usp=sharing

0 notes

Text

Review of “Audible Infrastructures” published

My first book review, of Alexandrine Boudreault-Fournier and Kyle Devine’s “Audible Infrastuctures” was published by Sound Studies:

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/20551940.2021.2005285

0 notes

Text

Conference paper published

Kurt Werner and I published our work on Paul De Marinis’ Gamelan circuit, specifically, it’s filter, in the 151st AES convention proceedings (this should be open access):

https://www.aes.org/e-lib/browse.cfm?elib=21506

Here’s the abstract:

This paper offers a study of the circuits developed by artist Paul DeMarinis for the touring version of his work Pygmy Gamelan. Each of the six copies of the original circuit, developed June-July 1973, produce a carefully tuned and unique five-tone scale. These are obtained by five resonator circuits which pitch pings produced by a crude antenna fed into clocked bit-shift registers. While this resonator circuit may seem related to classic Bridged-T and Twin-T designs, common in analog drum machines, DeMarinis’ work actually presents a unique and previously undocumented variation on those canonical circuits. We present an analysis of his third-order resonator (which we name the Gamelan Resonator), deriving its transfer function, time domain response, poles, and zeros. This model enables us to do two things: first, based on recordings of one of the copies, we can deduce which standard resistor and capacitor values DeMarinis is likely to have used in that specific copy, since DeMarinis’ schematic purposefully omits these details to reflect their variability. Second, we can better understand what makes this filter unique. We conclude by outlining future projects which build on the present findings for technical development.

0 notes