Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

The Importance of Healing Post-War: Breaking the Cycle of Violence

The destruction caused by war is not limited to shattered buildings or casualty statistics; its deepest wounds are often carried by the survivors. The ongoing conflicts in Ukraine, Gaza, Sudan, and other war-torn regions continue to leave lasting scars on individuals and societies. Beyond the visible devastation, the psychological and emotional toll of war fosters a cycle of trauma that fuels further violence. Unresolved grief and anger often transform into resentment, driving individuals toward revenge, radicalization, and continued conflict. This unseen damage perpetuates instability, making post-war healing a crucial but often overlooked necessity.

One of the most dangerous legacies of war is the generational hatred it instills. Entire communities that have suffered the loss of loved ones, homes, and security often find themselves consumed by bitterness. Without intervention, this grief hardens into animosity, creating an environment where children inherit the wounds of past conflicts. When reconciliation efforts and psychological recovery are absent, violence becomes an expected and accepted response. History has shown that war-battered regions frequently become recruitment grounds for extremist groups that exploit vulnerable individuals, offering them a distorted sense of belonging. Organizations such as ISIS and Boko Haram thrive in these conditions, turning unresolved pain into ideological fuel. Without addressing the root cause—trauma itself—these cycles of violence persist across generations.

The psychological toll of war is profound, reshaping the mental and emotional framework of those who endure it. Both civilians and soldiers experience long-term neurological and psychological consequences. Prolonged exposure to extreme stress alters brain function, heightening fear responses and diminishing rational decision-making. The result is often persistent anxiety, emotional instability, and an inability to move beyond the past. Many survivors live in a constant state of hypervigilance, haunted by memories of war. Despite the severity of these issues, mental health support is rarely prioritized in post-war recovery efforts. Governments and humanitarian organizations often focus on rebuilding infrastructure, neglecting the urgent need for psychological rehabilitation. This failure to address trauma ensures that its effects ripple through future generations.

A comprehensive approach to healing is essential for breaking the cycle of war-induced trauma. Various psychological therapies have proven effective in helping survivors process their experiences. Cognitive Processing Therapy (CPT) helps individuals reshape harmful beliefs tied to their trauma, while Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) enables the brain to reprocess distressing memories. Prolonged Exposure Therapy encourages survivors to confront rather than suppress their pain. Beyond clinical methods, alternative healing practices such as yoga, mindfulness, storytelling, and art therapy provide meaningful ways for individuals to regain a sense of agency over their lives. A holistic approach that acknowledges the interconnectedness of mental and physical well-being is crucial for lasting recovery.

The long-term consequences of neglecting psychological healing are evident in the recurring cycles of violence that plague many post-war societies. Sustainable peace cannot be achieved through treaties and ceasefires alone; it requires addressing the deep-seated wounds that fuel future conflicts. Governments, international organizations, and humanitarian efforts must prioritize mental health as an integral part of rebuilding war-affected communities. A commitment to trauma recovery, reconciliation programs, and accessible psychological services can break the generational cycle of violence, fostering societies where war is no longer an inherited burden. True peace is only possible when healing is given the same urgency as reconstruction, ensuring that war’s devastating impact does not shape the future.

Bloom, M. (2017). Small Arms: Children and Terrorism. Cornell University Press.

Grossman, D. (2009). On Killing: The Psychological Cost of Learning to Kill in War and Society. Back Bay Books.

Hoge, C. W., Auchterlonie, J. L., & Milliken, C. S. (2006). "Mental health problems, use of mental health services, and attrition from military service after returning from deployment to Iraq or Afghanistan." JAMA, 295(9), 1023-1032.

Koenen, K. C., Ratanatharathorn, A., Ng, L., McLaughlin, K. A., Bromet, E. J., Stein, D. J., ... & Kessler, R. C. (2017). "Posttraumatic stress disorder in the World Mental Health Surveys." Psychological Medicine, 47(13), 2260-2274.

0 notes

Text

The 21st Century Wars: Trauma, Suffering, and the Changing Battlefield

War has always been a constant in human history, but the wars of the 21st century differ greatly from those of the past. Technology has not only changed the battlefield but has also shaped the psychological trauma that individuals endure. Having closely followed conflicts in Ukraine and the Middle East, I often wonder what it must be like for the people caught in them. How does one cope when war infiltrates daily life, not just through physical destruction but also through the lasting scars of loss, displacement, and suffering? The lines between soldier and civilian, war and peace, have blurred beyond recognition.

The past two decades have seen an unprecedented shift in how wars are fought. Unlike the large-scale battles of the World Wars or even the Vietnam War, today’s conflicts are characterized by prolonged violence, asymmetrical warfare, and humanitarian crises. The 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, for instance, has resulted in massive civilian casualties and the displacement of millions (United Nations, 2022). In the Middle East, ongoing conflicts in Syria, Yemen, and Gaza have created generations of people who know nothing but war. The suffering extends far beyond the battlefield, affecting entire communities who bear the psychological and emotional burdens of conflict (International Rescue Committee, 2023).

The trauma of modern warfare is profound and multifaceted. Soldiers who survive combat often return home with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), struggling to reintegrate into civilian life (American Psychological Association, 2021). Unlike traditional wars where soldiers fought on defined battlefields, modern conflicts often involve urban combat, making it impossible to separate war zones from homes, schools, and hospitals. Israeli soldiers, for example, have shared their experiences of intense psychological strain, posting on social media platforms like TikTok about the horrors they witness and the emotional weight they carry (Haaretz, 2023). In Ukraine, videos of soldiers grieving their fallen comrades or grappling with the loss of their own humanity have surfaced, offering a raw and unfiltered glimpse into the mental toll of war (BBC, 2023).

Civilians suffer equally, if not more. The bombardment of cities, the destruction of infrastructure, and the loss of loved ones create deep and lasting wounds. Children growing up in war-torn regions experience severe psychological distress, often displaying signs of anxiety, depression, and developmental delays (Save the Children, 2022). Refugees fleeing conflict zones carry with them not only the trauma of war but also the pain of displacement and uncertainty. The Syrian refugee crisis, for example, has left millions in a state of statelessness, struggling to rebuild their lives while coping with the lingering memories of violence and loss (UNHCR, 2023).

Social media has intensified the emotional toll of war. Unlike past generations who learned about war through newspapers or television broadcasts, people today are exposed to real-time images and videos of destruction and suffering. This constant exposure can lead to secondary trauma, where individuals who are not directly involved in the conflict still experience distress, anxiety, and a sense of helplessness (National Institute of Mental Health, 2022). The ability to witness war so intimately, often through the eyes of those suffering, makes it impossible to remain detached.

As someone who has never lived through war but has studied its impact, I find it deeply unsettling how modern warfare has dehumanized suffering. There was once a time when war was fought face-to-face, with some element of honor and humanity in combat. Today, war often involves indiscriminate bombings, drone strikes, and siege tactics that target civilians as much as combatants (Human Rights Watch, 2023). The trauma that results from this is profound, affecting not just those on the battlefield but also those who witness war from afar.

The wars of the 21st century have reshaped the landscape of human suffering. Technology and modern military tactics have made war more devastating, creating lasting trauma for soldiers, civilians, and even distant observers. As we move further into an era where war is an ever-present reality, it is crucial to understand its psychological consequences and find ways to support those who endure its horrors.

References

American Psychological Association. (2021). PTSD in war veterans.

BBC. (2023). War in Ukraine: The mental toll on soldiers.

Haaretz. (2023). Israeli soldiers on TikTok: A glimpse into war trauma.

Human Rights Watch. (2023). The impact of modern warfare on civilians.

International Rescue Committee. (2023). The humanitarian crisis in conflict zones.

National Institute of Mental Health. (2022). Secondary trauma and social media exposure.

Save the Children. (2022). War and its effects on child psychology.

UNHCR. (2023). The Syrian refugee crisis: A decade later.

United Nations. (2022). Civilian casualties in the Ukraine conflict.

0 notes

Text

The Cold War: Redefining War and Global Relations

World War II was one of the most destructive occurrences in human history, leaving large parts of Asia, Europe, and Africa devastated. Cities were leveled to the ground, infrastructure was lost, and the economic cost was staggering. Although the war ended in 1945, its effects dominated the world for decades. The immediate post-war period witnessed severe economic crises, inflation, and shortages of food, with most nations finding it difficult to rebuild. Yet, perhaps the most far-reaching impact of World War II was the Cold War, an era of extreme geopolitical competition between the Soviet Union and the United States.

After World War II, two superpowers came into existence whose ideologies clashed with each other: the capitalist America and the communist Soviet Union. The war had consolidated their dominance in various regions of the globe, and soon their ideological rift resulted in an arms race, proxy wars, and political standoffs. The Cold War was marked by armament, intelligence gathering, and economic rivalry, with both nations trying to expand their power around the world.

One of the most important features of the Cold War was nuclear proliferation. Both the Soviet Union and the United States built enormous arsenals of nuclear weapons, creating a state of mutual assured destruction (MAD). The threat of nuclear destruction hung over the globe, shaping international diplomacy and military tactics. The Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962 brought the world to the edge of nuclear war, illustrating the fragility of this era.

AMS (Arms Management and Strategic Control) was very important in softening some of the Cold War tensions. Diplomatic efforts such as the Strategic Arms Limitation Talks (SALT), the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty (ABM), and subsequent Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START) were essential in avoiding outright military confrontation between the superpowers. These treaties sought to constrain the manufacture and deployment of nuclear weapons, instituting a context for managed competition instead of naked confrontation.

The Cold War had far-reaching effects, most of which persist in the modern global politics. Some of its major issues include proxy wars, political instability, economic hardships, the division of Europe, and psychological effects. Rather than confrontation, the Soviet Union and the U.S. fought proxy wars in nations such as Korea, Vietnam, and Afghanistan. These wars destroyed local economies and populations, leaving deep scars in these countries. This competition created the destabilization of governments across the globe.

The U.S. and the Soviet Union regularly backed tyrannical regimes that shared their respective ideologies, resulting in human rights abuses and civil wars. Most nations were compelled to decide between aligning either with the U.S. or the USSR, which shaped their economic policies. The Cold War also resulted in over-militarization, draining resources from development projects in both superpowers and their allies. Europe was divided into two spheres of influence, with the Iron Curtain representing the division between East and West. Germany was physically divided into East and West, resulting in decades of separation and political tension. Similar to the psychological damage inflicted by World War II, the Cold War period generated suspicion and fear among numerous societies. Ongoing threats of nuclear war, spying, and repression of ideologies all added to increased anxiety among people.

The Cold War radically altered the character of war and world relations. In contrast to the earlier wars that were waged with conventional military confrontations, the Cold War was characterized by new types of warfare, such as ideological warfare, spying, economic coercion, and cyber warfare. The application of psychological warfare, propaganda, and intelligence collection missions was central in exerting influence. Foreign relations also changed, with organizations such as the United Nations (UN) and alliances such as NATO and the Warsaw Pact playing central roles in upholding equilibrium. The Cold War period also witnessed the rise of non-aligned movements, as nations wanted to stay away from the superpower conflict. The transition from traditional warfare to proxy wars and diplomatic chess moves established a precedent for contemporary geopolitical tactics.

Whereas World War II restructured the world politically and economically, the Cold War cemented divisions and created new conflicts that lasted for almost half a century. Although it never turned into open war between the two superpowers, the Cold War has a legacy of devastation in the form of proxy wars, economic hardship, and ideological struggles. The effects of Cold War policies and antagonisms persist even today in the global arena, reminding us of the imperative to employ diplomacy and cooperation to avoid another era of extended tension across the globe.

Gaddis, John Lewis. The Cold War: A New History. Penguin, 2005.Hobsbawm, Eric.

The Age of Extremes: The Short Twentieth Century, 1914–1991. Michael Joseph, 1994.Westad, Odd Arne.

The Cold War: A World History. Basic Books, 2017.

Leffler, Melvyn P. "The Cold War: What Do ‘We Now Know’?" American Historical Review, vol. 104, no. 2, 1999, pp. 501-524.Nye, Joseph S.

"The Cold War and After: Prospects for Peace." Foreign Affairs, vol. 71, no. 2, 1992, pp. 66-79.

0 notes

Text

World Wars and the Role of Media: How It Changed the Nature of Conflict

In 1914, as World War I erupted, a young soldier named Thomas, stationed on the Western Front, received letters from home filled with patriotic zeal. The newspapers back in Britain painted the war as a noble fight, omitting the horrors of trench warfare. However, years later, his younger brother William, who fought in World War II, experienced a different reality. By then, radio broadcasts and photographs showed civilians the grim reality of war. Unlike Thomas, William’s family understood the dangers he faced. This shift in perception was largely due to the evolution of media.

During World War I (1914–1918), the media was heavily censored. Governments controlled information to maintain morale and support for the war effort. Newspapers published articles filled with patriotic messages, avoiding details about battlefield horrors. Propaganda posters were widely used to encourage enlistment and demonize the enemy (Horne, 2001). For instance, Britain’s "Your Country Needs You" posters became a symbol of wartime duty. Similarly, Germany and the United States used propaganda to shape public opinion.

By the time World War II (1939–1945) began, the media had transformed. Radio became a major source of real-time news, allowing people to hear battlefield reports. The BBC played a crucial role in broadcasting updates, while Nazi Germany used radio for propaganda under Joseph Goebbels’ direction (Taylor, 1995). Meanwhile, photojournalism brought war images directly to the public. The photographs of the Holocaust and the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki left a lasting impact, making people question the morality of war.

Unlike World War I, where governments heavily controlled information, World War II saw more exposure of war’s brutal realities. Although propaganda was still used, news reports and photographs began showing the destruction and human cost. The public reaction to images from concentration camps and bombed cities created global conversations about war ethics (Carruthers, 2000).

The changing role of media during the world wars also influenced government policies. Public pressure increased after graphic reports emerged. For example, during World War II, reports of Nazi atrocities pushed the Allies to focus on humanitarian efforts. Similarly, the dropping of atomic bombs in Japan led to ethical debates, largely driven by media coverage (Overy, 2009). The way media portrayed events shaped diplomatic decisions and post-war policies, such as the establishment of the United Nations.

The evolution of media during the world wars set the stage for its role in modern conflicts. Today, social media, live broadcasts, and citizen journalism continue to shape public perception. Unlike controlled propaganda of the past, information now spreads rapidly, sometimes making wars harder to justify (Thompson, 2011). The Vietnam War, for example, saw the first "television war," where raw footage influenced protests and policies.

The world wars marked a turning point in the relationship between media and conflict. While World War I saw strict censorship and propaganda, World War II introduced more direct reporting and photojournalism, making war realities harder to hide. This shift influenced public opinion, policies, and the nature of global conflict. Today, with digital media, war coverage is more immediate and widespread, continuing the legacy of how media shapes history.

Carruthers, S. L. (2000). The media at war: Communication and conflict in the twentieth century. Macmillan.

Horne, J. (2001). State, society and mobilization in Europe during the First World War. Cambridge University Press.

Overy, R. (2009). The bombing war: Europe 1939-1945. Penguin.

Taylor, P. M. (1995). Munitions of the mind: A history of propaganda from the ancient world to the present day. Manchester University Press.

0 notes

Text

Blood and Chains: How Colonialism Reshaped War and Human Suffering

"I was fourteen when they took me. They said I was needed for the war effort, that I would be helping my country. I was taken to a comfort station in Najin, forced to serve men day and night. They beat us if we cried, starved us if we resisted. We were not seen as humans—only tools for their war."

Colonialism changed the nature of war in ways that had never been seen before, intertwining military conquest with systemic exploitation of populations on an unprecedented scale. From the forced sexual slavery of "comfort women" under Japanese imperialism to the brutality inflicted upon the Congolese under Belgian rule, colonial wars introduced new levels of organized violence, racial hierarchy, and resource-driven conflicts that left long-lasting scars on nations and peoples.

Japan’s imperial expansion in the 20th century was characterized by extreme brutality, with the "comfort women" system being one of the most heinous examples of wartime sexual slavery. As Yoshimi (2000) documents, the Japanese military systematically recruited and coerced women from Korea, China, and the Philippines into sexual servitude, operating under the guise of providing "comfort" to soldiers. The Najin Massacre, though lesser known than the Nanjing Massacre, exemplifies the unrestrained violence that defined Japan’s occupation policies. Women and girls were abducted, raped, and murdered, with survivors left physically and emotionally shattered. Tanaka (2002) highlights how the imperial Japanese administration institutionalized this form of sexual violence, rationalizing it as a necessary evil to maintain morale among troops. This dehumanization was not an unintended consequence but a structural feature of colonial warfare.

Belgium’s colonial atrocities in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (then the Congo Free State) further demonstrate how colonialism transformed war into a systematic exploitation of people and resources. Under King Leopold II, the Belgian administration turned the region into a massive forced labor camp, where Congolese men, women, and children were subjected to gruesome punishments for failing to meet rubber quotas. Hochschild (1998) details how millions perished due to starvation, disease, and brutal executions, with entire villages burned and mutilations becoming a common form of terror. The Belgian colonial war was not fought on battlefields but within the everyday lives of the Congolese people, who lived under a regime of relentless violence designed to extract wealth for European benefit.

Similarly, British colonial warfare in India during World War II led to devastating consequences, particularly in the form of engineered famines. Mukerjee (2010) argues that the Bengal Famine of 1943, which killed millions, was exacerbated—if not deliberately caused—by British wartime policies that prioritized feeding their troops while disregarding Indian civilians. Churchill’s government refused to divert food supplies to the starving population, with Churchill himself dismissing Indian suffering as inconsequential. This use of starvation as a weapon of war highlights how colonial powers did not need direct combat to inflict mass casualties; instead, they controlled resources and supply chains to devastating effect.

The nature of war under colonialism was distinct because it was not confined to traditional battlefronts. Instead, it invaded homes, bodies, and economies, leaving societies fractured long after formal conflicts ended. Fanon (1961) describes colonial war as a psychological as well as a physical battle, wherein the colonized are stripped of their humanity, reduced to expendable bodies in service of imperial interests. The introduction of industrial-scale violence, forced labor, sexual slavery, and resource extraction blurred the lines between war and governance, turning entire populations into unwilling participants in conflicts they neither started nor could escape.

The legacies of these colonial wars persist today. Survivors of Japan’s comfort women system continue to fight for recognition and justice, facing denialism from the Japanese government. The Congo remains scarred by the economic and social devastation wrought by Belgium, with cycles of violence continuing as different factions fight over resources that were once plundered by Europeans. In India, the memory of the Bengal Famine serves as a reminder of how colonial policies treated human lives as secondary to imperial objectives.

Colonialism did not just change how wars were fought—it redefined who suffered and for what purpose. The comfort women of Najin, the mutilated laborers of the Congo, and the starving families of Bengal all bore the costs of wars they did not choose, waged by empires that saw them as tools rather than people. As Said (1978) argues in Orientalism, colonial ideology framed the colonized as inherently inferior, justifying their suffering as a necessary byproduct of civilization and empire. These narratives continue to shape historical memory, often downplaying the full extent of colonial violence.

To understand modern conflicts, we must acknowledge how colonialism transformed war into a totalizing force, affecting not just soldiers but entire populations. Recognizing these histories is not just about remembering the past—it is about challenging the structures of power and exploitation that still shape our world today.

Fanon, F. (1961). The Wretched of the Earth. Grove Press. Hochschild, A. (1998). King Leopold's Ghost. Houghton Mifflin. Mukerjee, M. (2010). Churchill's Secret War. Basic Books. Pakenham, T. (1991). The Boer War. Random House. Said, E. (1978). Orientalism. Pantheon Books.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Innocence Lost: The Exploitation of Children in Religious Conflicts

In a small village near Jerusalem during the First Crusade, Elias, a young boy, watched as knights marched past his home, bearing the cross. These men claimed to act on divine will, promising salvation and glory. When Elias’s father, a trader, warned of massacres in nearby towns, Elias asked, "How could God desire such violence?" His question echoed through history, exposing how religion, manipulated for power, has often justified wars, forced conversions, and even the exploitation of children, leaving lasting scars on societies.

Religion, while a source of spiritual guidance and community, has also been wielded as a tool to mobilize and control populations. The Crusades, the Spanish Inquisition, and the Thirty Years’ War are prime examples where religious narratives were distorted to justify violence. Children, in particular, were not spared from this manipulation. Their innocence and devotion were exploited, most tragically during the Children’s Crusade (1212). This movement, a mix of myth and historical reality, saw thousands of children from France and Germany embarking on a journey to the Holy Land, convinced by preachers that God had chosen them to reclaim Jerusalem peacefully.

Historical accounts suggest that many children were either sold into slavery or perished from hunger, exposure, and exhaustion. This event exemplifies how religious fervor and societal manipulation can exploit vulnerable groups. Scholar Gary Dickson, in The Children’s Crusade: Medieval History, Modern Mythistory, argues that this tragedy reflects broader medieval dynamics, where religious zeal often overshadowed reason and led to catastrophic outcomes. The trauma endured by these children reverberated through their communities, sowing distrust and disillusionment with institutional religion.

The exploitation of children in religious contexts isn’t limited to medieval Europe. Forced indoctrination and participation in religiously motivated conflicts continue to manifest in modern societies. The use of child soldiers in regions such as Africa and the Middle East echoes the exploitation seen in the Children’s Crusade. Groups like Boko Haram and ISIS manipulate religious ideology to recruit children, indoctrinating them into violent causes. The effects on these children psychological trauma, loss of identity, and intergenerational cycles of violence mirror the scars left by historical religious wars.

The Spanish Inquisition also targeted young individuals, often coercing children to testify against their families under the guise of protecting the faith. Children were caught in a system where fear and indoctrination eroded trust within communities. Karen Armstrong, in Fields of Blood, highlights how religious institutions often co-opted familial bonds, turning them into mechanisms of control. This breakdown of trust has long-term societal effects, perpetuating cycles of suspicion and division.

The Thirty Years’ War further illustrates how children became casualties of religiously fueled conflicts. The devastation of Central Europe led to widespread famine and disease, disproportionately affecting the young. The war’s brutality, justified by Protestant and Catholic leaders invoking divine will, created a generation scarred by loss and displacement. Hannah Arendt’s concept of the “banality of evil” is apt here; ordinary individuals, believing they served a higher purpose, perpetuated systemic violence that uprooted entire communities, including children.

The psychological impact of these events lingers in societies today. Johan Galtung’s theory of structural violence helps explain how historical trauma becomes embedded in social systems. The exploitation of children for religious or ideological purposes has created lasting legacies of distrust in institutions, perpetuated cycles of poverty and marginalization, and hindered reconciliation. In places like Israel and Palestine, where religious narratives are deeply intertwined with national identity and conflict, children grow up in environments shaped by historical grievances and ongoing violence. Edward Said, in Orientalism, critiques how historical narratives are weaponized to perpetuate cycles of division, often at the expense of the most vulnerable children.

The scars left by religiously justified violence are not confined to history. Modern societies continue to grapple with the aftermath of such exploitation. Forced conversions during the Spanish Inquisition erased cultural identities, leading to generational trauma among Jewish and Muslim communities in Spain. Similarly, the Crusades’ legacy of interfaith animosity still influences global politics, particularly in the Middle East. Children, born into these conflicts, inherit the trauma and biases of previous generations.

Religious indoctrination of children, whether through direct involvement in conflict or through education systems that perpetuate divisive narratives, remains a pressing issue. Forced adherence to a singular religious identity often denies children the opportunity to explore their individuality. The effects of such indoctrination manifest as deep-seated societal divisions, as seen in communities worldwide.

Elias’s story and the tragedies of the Children’s Crusade remind us of the human cost of religious manipulation—innocence lost, communities torn apart, and generational trauma that persists. By critically examining these historical patterns, as scholars like Armstrong and Dickson urge, we can recognize the mechanisms of exploitation and work to dismantle them. Religion need not be a source of division; it can inspire unity and compassion when freed from the clutches of political and ideological manipulation.

Understanding these legacies is essential in addressing the roots of contemporary conflicts. Children, as the most vulnerable members of society, deserve protection from exploitation. By drawing lessons from history and prioritizing education that fosters critical thinking and empathy, we can hope to create a world where faith serves as a bridge rather than a battleground.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Dark Legacy of Ancient Wars: Dehumanization of Women from Carthage to Today

In the ancient city of Carthage, a scene unfolds that mirrors the horrors of modern-day war zones. The sky is painted with flames as Roman soldiers invade the city, tearing down homes, enslaving survivors, and wreaking havoc on the very fabric of the society. Among the most vulnerable in this destruction were the women of Carthage, whose fate was sealed not only by their defeat but by the deep dehumanization they faced at the hands of their conquerors. The women, once revered for their cultural significance and strength, were labeled as barbaric, accused of witchcraft, black magic, and even of enslaving babies. This image of the Carthaginian women as cruel and monstrous was strategically cultivated by the Romans, whose desire to obliterate not just the city but its spirit extended to degrading its survivors. It was a deliberate attempt to strip Carthage of its identity, portraying its women as dangerous and subhuman in order to justify their subjugation.

The emotional weight of this historical injustice is not lost on us today. In contemporary war zones like Syria, Afghanistan, or parts of Africa, women continue to face similar horrors. They are trafficked, subjected to sexual violence, and treated as spoils of war. These atrocities often stem from a dehumanizing mindset that, much like in ancient times, seeks to erase the humanity of those seen as "other." The women in these modern conflicts, much like the women of Carthage, become symbols of the power struggles around them victims not just of physical violence but of societal attempts to crush their identity and spirit.

"When silence wears a uniform of blue, and freedom stands chained to the wall, Wars claim victories while women pay the price of someone else's call."

The birth of organized warfare in early civilizations such as Mesopotamia, Egypt, and later, Carthage, marked a shift in human history. It wasn’t just about fighting for resources; it was about asserting power, shaping identity, and erasing the enemy’s very existence. The Assyrians, for example, were known for their brutal military campaigns, leaving behind detailed accounts of their victories that painted their enemies as barbaric and subhuman, particularly women and children. Similarly, in the Battle of Kadesh in 1274 BCE, the Egyptians faced off with the Hittites, not just in a struggle for control of land, but in a war that was meant to define the power structures of the ancient world. These wars were deeply psychological, with narratives crafted to instill fear and demoralize opponents.

"The original relief depicting the Battle of Kadesh – from the Ramesseum"

In Carthage, the psychological assault on its women was part of this broader dehumanization. The Romans painted Carthaginian women as evil, engaging in black magic, a tactic designed to strip away their dignity and reduce them to mere tools of war. Their very existence was criminalized, and the stories of their supposed witchcraft were used to justify their capture and enslavement. This served as a warning to others who might dare defy Rome, illustrating just how far the Romans would go to maintain control.

"Alternative naartives developed by the Vicoties Party to justify the astocoties done by them."

In many ways, the dehumanization of women in warfare has remained unchanged. Social exchange theory, which looks at how individuals weigh the costs and benefits of their relationships, can help explain why women continue to be treated as spoils of war. In this context, women are seen as assets, their value measured by their ability to serve the needs of the victor. Their physical bodies become sites of power struggles, their identities erased to reinforce the dominance of the invader. This dynamic is still evident in modern-day conflicts, where sexual violence is often used as a weapon to assert control and demoralize communities.

The caveman courting theory also sheds light on the ancient and modern exploitation of women in war. This theory suggests that, from an evolutionary standpoint, the capture of women during conflict was seen as a way to assert dominance and ensure reproductive success. While this theory has been debated, its underlying truth persists in the practices of warfare throughout history, where women are often seen as prizes to be won or punished for the perceived crimes of their people. In Carthage, as in many other ancient conflicts, women became central to the narrative of conquest. Their subjugation served not just as an act of violence but as a symbolic erasure of the enemy’s identity.

The emotional toll of this dehumanization cannot be overstated. For women, both in ancient wars and in modern-day conflicts, the experience of being reduced to an object of war leaves deep psychological scars. The Carthaginian women, after being captured and enslaved, lost not only their homes and families but their very sense of self. Today, women in refugee camps or those caught in conflict zones experience a similar loss of identity, forced to adapt to environments where their trauma is ignored, and their humanity is questioned.

The concept of the "lost generation" also resonates deeply in both ancient and modern conflicts. In ancient times, the destruction of Carthage was not just a military victory; it was the obliteration of a civilization. The surviving women, like the survivors of modern-day conflicts, were left to rebuild lives that had been shattered by war. The children, too, bore the scars of this destruction, their future's uncertain as they grew up in the ruins of their once-vibrant societies. In the present day, the "lost generation" refers to the children raised in war zones, whose futures are defined by displacement, violence, and trauma. These young people, like those in ancient times, are often left without the tools they need to rebuild their societies, perpetuating cycles of poverty, violence, and despair.

Cynthia Enloe, a prominent scholar on militarism, has written extensively about the role of women in wartime, emphasizing how their bodies become battlegrounds in larger struggles for power. Her work highlights the fact that women’s roles in conflict are often reduced to symbolic representations of the society they belong to, and their suffering becomes a tool to undermine the enemy. Gerda Lerner, another scholar, traces the roots of patriarchy to these ancient practices, arguing that warfare played a crucial role in establishing and reinforcing gender hierarchies. The commodification of women in war, she argues, has its origins in these early conflicts, where women were treated as objects to be controlled, used, and discarded at will.

A case in point is the violence unleashed on women in ancient times, such as the sacking of Carthage, and the systemic sexual atrocities in contemporary conflicts. All this shows the trend to brutalize the vulnerable cuts across the ages. At the same time, Hammurabi's Code, for instance, was meant to be the embodiment of justice that would protect people from similar brutality. For instance, women in ancient Rome were viewed as war spoils. Their misery was either ignored or dismissed in favor of the military interests. The martial virtues are idealized in Roman culture, and such a setup justified the use of force against women, reducing them to mere conquest objects in the name of war. This hypocrisy in legal mechanisms made possible the normalising of such violence, for the dehumanizing aspect of women has, in actuality, become the unfortunate spin-off of conquest.The very tragic truth of this, however, is that all through the course of time, such violence continues in modern war zones and affects women's suffering, though through international human rights law developed. Even with deep-rooted misogyny and women's contempt, women's bodies cannot be desensitized. Hypocrisy from the past, when the cultural norms justified the suffering of women, continues to ring in the ears today. Despite the progress of legal codes and global agreements, it remains haunted by the primitive nature of human aggression and dehumanization of women.

Bileta, V., & Venner, J. (2023, July 17). The Punic Wars: How Did the Romans Crush Carthage? TheCollector. Retrieved December 21, 2024, from https://www.thecollector.com/the-punic-wars-how-did-the-romans-crush-carthage/

Bileta, V., & Venner, J. (2023, July 17). The Punic Wars: How Did the Romans Crush Carthage? TheCollector. Retrieved December 21, 2024, from https://www.thecollector.com/the-punic-wars-how-did-the-romans-crush-carthage/

Code of Hammurabi | Summary & History. (2024, October 28). Britannica. Retrieved December 21, 2024, from https://www.britannica.com/topic/Code-of-Hammurabi

Nickerson, C. (2023, October 25). Social Exchange Theory of Relationships: Examples & More. Simply Psychology. Retrieved December 21, 2024, from https://www.simplypsychology.org/what-is-social-exchange-theory.html

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why We Must Remember?

"It is not enough to fight for the living; we must also remember the dead and honor their sacrifices."

In a camp a small, frail 8-year-old child sitting scratching at his body, "There's no clean water to bathe with. I'm itching all the time," says Ahmad with frustration and sadness. Other children shun him because of his rash. Ahmad's mother, Fatima, sits by helplessly, saying, "He got a fever. The itching is constant, and he cannot sleep. The water is not clean, and we don't have the basics such as shampoo and soap."Nearby, 7-year-old Wahid sits in pain, pointing to a spreading rash. His mother adds, "Even walking is painful for him."These stories, which have been sourced from the UNICEF Palestine page, represent a fraction of the suffering of thousands of children caught in war zones like Gaza. They are exposed to diseases and indignities that no child should be subjected to due to a lack of clean water, sanitation, and medical care. As we discuss their struggles, similar stories unfold worldwide because people decide to keep silent.This is no isolated tale it reflects systemic failures in international policy and governance. The plight of children like Ahmad and Wahid shows how war spares no one, least of all the innocent, further underlining the need for the urgency of these problems.

"Amidst the shattered ruins, a child's innocence clings to hope, her eyes searching for a world that feels safe again. Her tiny presence speaks volumes of resilience in a space consumed by despair."

War has always cut human history, but rules of war have evolved in time. Ancient texts, such as the Mahabharata, talked about the destructive nature of war and provided ethical guidelines for how to conduct it: that it should be done in specified areas during daylight and not on civilians. Similarly, the Quran stresses the value of life, which includes strict prohibitions against causing harm to non-combatants or destroying resources.

In Christian theology, Augustine and Aquinas developed the concept of "just war," which insists that wars should have just causes and the purpose of restoring peace.In fact, history demonstrates the many occasions when they are violated. Modern war, from World War to present-day warfare, makes civilians into "collateral damage." Industrialization and technology have made war a force of impersonal, indiscriminate destruction. As Napoleon Bonaparte wrote, "The world suffers a lot from the violence of bad people because of the silence of good people." His words remind us of the moral vacuum that ensues when ethical lines are broken by ambition and hatred.

"A rescuer holds a lifeless child, haunted by the weight of innocent lives lost. Behind the term "collateral damage" lies unbearable human grief and pain."

Genocide represents one of war’s darkest consequences. Coined by Raphael Lemkin, the term combines "geno" (race) and "cide" (to kill). Lemkin’s advocacy, driven by the Holocaust’s horrors, led to its recognition as a crime under international law. Yet, genocide remains a tragic reality. From the Armenian Genocide to Rwanda, Cambodia, and Myanmar’s persecution of the Rohingya, these atrocities seek to annihilate entire communities, erasing lives, cultures, and histories. The United Nations (UN) and international laws established, such as the Geneva Conventions, are all designed to prevent war crimes and to protect civilians. Yet, their implementation often fails. For instance, it was during the genocide in Rwanda and Bosnia that UN failures in peacekeeping and accountability were institutional.

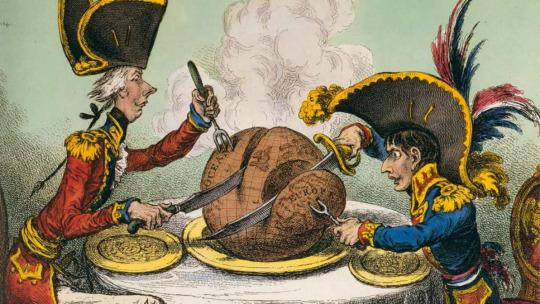

"The cartoon highlights the grim irony of war, where peace is postponed until the destruction is complete."

Edward Said and similar scholars attack colonial legacies that allow divisions and conflicts to continue. Said further explains in Orientalism how the colonial powers ensured that "us versus them" narratives allowed cycles of violence to be sustained long after the departs. Such divisions are prevalent in the Middle East and Africa, showing how history shapes the problem today.The plight of Gaza's children is a repeated failure. International bodies must prioritize availability of clean water, medical care, and education in those conflict zones. Otherwise, as Napoleon warned, "the silence of good men allows evil to triumph".

War's impact transcends generations, leaving physical, emotional, and cultural scars. The trauma experienced by children like Ahmad and Wahid reflects the broader consequences of conflict. Remembering these stories is not just a moral duty; it is a necessity for shaping a better future.As Napoleon Bonaparte reminds us, "Inaction breeds danger. Men who are responsible for good, responsible men, will stagnate in time, especially if they think themselves safe." The Rwandan Genocide killed nearly a million people in 100 days.

This is what happens when the world keeps silent. The same can be said about the Holocaust: horrors led to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and "never again."Yet, as the wars in Syria, Myanmar, and elsewhere continue, we see history repeating itself. Studying war, trauma, and genocide allows us to confront these patterns. It teaches us about resilience and survival, as seen in children like Ahmad and Wahid, whose stories symbolize both suffering and hope.

"Amidst the ruins of a shattered car, the child's gentle smile reflects resilience hope persisting even in the face of devastation."

In this blog series, we will focus on ancient, medieval, and modern periods of history to give closer attention to these themes. The first part will uncover some early origins of war and their ethical dilemmas along with the very first genocides in ancient civilizations. In the second part, we will assess how religion and power played central roles in medieval conflicts including religious wars and persecution of whole communities. Finally, the third section will take us into the present world by discussing the latest genocides, war crimes, and how technology is impacting contemporary warfare.

We trace here how the colonial powers carried on their "us and them" narratives and enshrined divisions even well after the colonialism phase was over, fuelling conflict. We will also see how these legacies of division continue to influence the conflicts we are seeing today-from the Middle East to Africa, where wars, genocides, and war crimes continue to rip apart communities and families. Case studies from India, Syria, Rwanda, and Sri Lanka among others will enable us to understand better how human beings, divided by historical forces, continue to divide themselves, perpetuating cycles of violence and trauma.

Within our blog series Faces of Conflict, we strive to shed light on the many layers of the reality of war and its consequences. Inspired by the Roman virtue of Veritas, where truth is the underlining point, our investigation finds and searches for the more sinister and harsh realities that arise within conflict, mainly with deep effects on the vulnerable victim, especially women and children. By sharing these stories and perspectives, we challenge silence and complicity, allowing injustice to flourish, as well as throw a light on how war crimes have evolved and caused havoc over time.

Through this journey, we move past recounting atrocities to identify tangible solutions that can deliver true justice restoring dignity, healing trauma, and promoting peace. It's through tracing historical patterns and analyzing modern implications we are seeking to find failures in the system and motivate accountability and reform. Recognizing the legacy of war crimes is not only key to honoring the past but for creating a future free of cycles of violence and injustice.

Frankel, J. (2024, December 6). War - Conflict, Causes, Consequences. Britannica. Retrieved December 10, 2024, from https://www.britannica.com/topic/war/Social-theoriesHow do you define genocide?

(2022, April 4). BBC. Retrieved December 10, 2024, from https://www.bbc.com/news/world-11108059

UNICEF State of Palestine. (n.d.). Unicef. Retrieved December 10, 2024, from https://www.unicef.org/sop/

2 notes

·

View notes