faggottrry

84 posts

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Photo

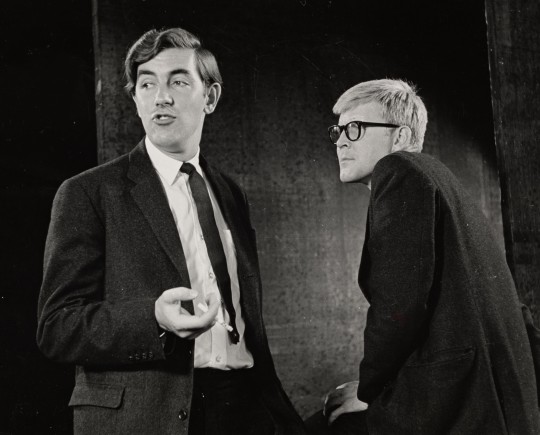

Peter Cook and Alan Bennett performing in Beyond the Fringe

44 notes

·

View notes

Photo

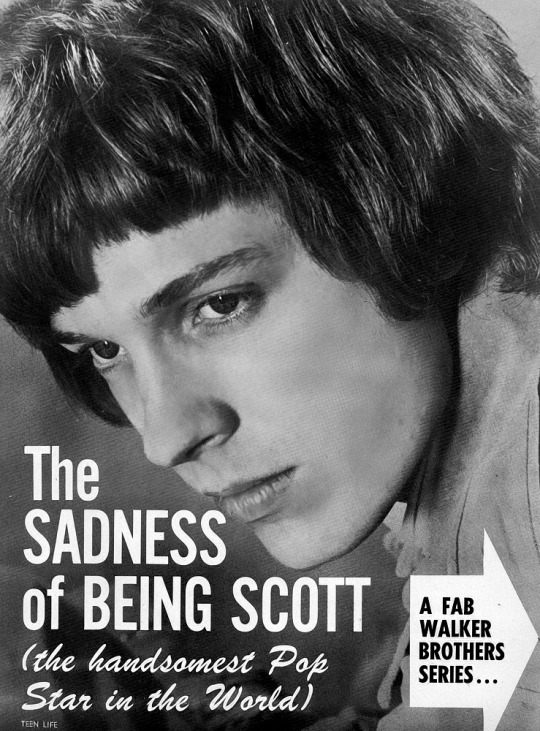

The Twilight Zone - Season 1 Episode 19 (1960) “The Purple Testament”

435 notes

·

View notes

Text

111 notes

·

View notes

Text

🖤Donovan🤍

he’s probably my favorite folk singer

107 notes

·

View notes

Photo

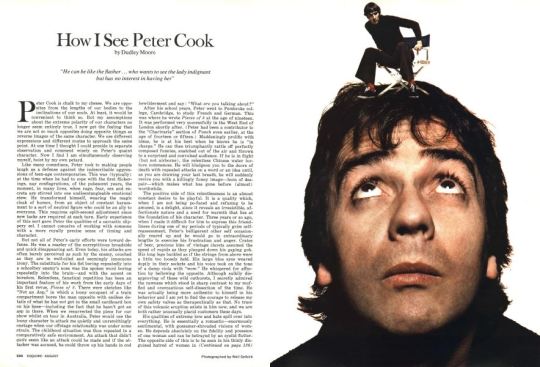

How I See Peter Cook by Dudley Moore, Esquire August 1 1974

Peter Cook is chalk to my cheese. We are opposites from the lengths of our bodies to the inclinations of our souls. At least, it would be convenient to think so. But my assumptions about the extreme polarity of our characters no longer seem entirely true. I now get the feeling that we are not so much opposites doing opposite things as reverse images of the same character. We use different expressions and different routes to approach the same point. At one time I thought I could preside in separate observation and comment wisely on Peter’s quaint character. Now I find I am simultaneously observing myself, hoist by my own petard.

Like many comedians, Peter took to making people laugh as a defense against the indescribable aggressions of teen-age contemporaries. This was (typically) at the time when he had to cope with the first flickerings, nay conflagrations, of the pubescent years, the moment, in many lives, when rage, fear, sex and excreta are stirred into one undisentangleable emotional stew. He transformed himself, wearing the magic cloak of humor, from an object of constant harassment to a sort of neutral figure who could be an ally to everyone. This requires split-second adjustment since new tacks are required at each turn. Early experience of this sort gave Peter the qualities of a sarcastic slippery eel. I cannot conceive of working with someone with a more royally precise sense of timing and character.

But not all of Peter’s early efforts were toward defense. He was a master of the surreptitious broadside and quick disappearing act. Even today, his attacks are often barely perceived as such by the enemy, couched as they are in well-oiled and seemingly innocuous irony. The substitute for his fist boring repeatedly into a schoolboy enemy’s nose was the spoken word boring repeatedly into the brain—and with the accent on boredom. Relentless, fanatical repetition has been an important feature of his work from the early days of his first revue, Pieces of 8. There were sketches like “Not an Asp,” in which a loony occupant of a train compartment bores the man opposite with endless details of what he has not got in the small cardboard box on his knee—including the fact that he hasn’t got an asp in there. When we resurrected the piece for our show whilst on tour in Australia, Peter would use the loony character to attack me quietly and unremittingly onstage when our offstage relationship was under some strain. The childhood situation was thus repeated in a comparatively safe environment. An attack that didn’t quite seem like an attack could be made and if the attacker was accused, he could throw up his hands in cod bewilderment and say: “What are you talking about?”

After his school years, Peter went to Pembroke college, Cambridge, to study French and German. This was where he wrote Pieces of 8 at the age of nineteen. It was performed very successfully in the West End of London shortly after. (Peter had been a contributor to the “Charivaria” section of Punch even earlier, at the age of fourteen or fifteen.) Maddeningly prolific with ideas, he is at his best when he knows he is “in charge.” He can then triumphantly rattle off perfectly composed funnies, snatched out of the air and thrown to a surprised and convulsed audience. If he is in flight (but not airborne), the relentless Chinese water torture commences. He will bludgeon you to the doors of death with repeated attacks on a word or an idea until, as you are drawing your last breath, he will suddenly revive you with a killingly funny image—born of despair—which makes what has gone before (almost) worthwhile.

The positive side of this relentlessness is an almost constant desire to be playful. It is a quality which, when I am not being po-faced and refusing to be amused, is a delight, since it reveals an irresistible, affectionate nature and a need for warmth that lies at the foundation of his character. Three years or so ago, when I made it difficult for him to express this friendliness during one of my periods of typically grim self-reassessment, Peter’s belligerent other self occasionally reared up and he would go to extraordinary lengths to exercise his frustration and anger. Crates of beer, precious bins of vintage clarets assumed the speed of rapids as they plunged down his gaping gob. His long legs buckled as if the strings from above were a little too loosely held. His large blue eyes weaved dopily in their sockets and his voice took on the tone of a damp viola with “wow.” He whispered for affection by bellowing the opposite. Although sulkily disapproving of these wild outbursts, I secretly admired the rawness which stood in sharp contrast to my muffled and overcautious self-dissection of the time. He was actually being more authentic to himself in his behavior and I am yet to find the courage to release my own safety valves as therapeutically as that. No trace of this volcanic eruption exists in him now, and we are both rather unusually placid customers these days.

His qualities of extreme love and hate spill over into everything. He is essentially a romantic—enormously sentimental, with gossamer-shrouded visions of women. He depends absolutely on the fidelity and presence of one woman and can be betrayed by an eyelid flutter. The opposite side of this is to be seen in his thinly disguised hatred of women in general. Perhaps, by the alchemy of marriage, he converts that unbearable hate to a paradoxical devotion, because for every violent spark of hatred for women that leaps in his subconscious, there is a regular bonfire of love for his beautiful elf wife, Judy. He was led to marriage—at least this second time, his first ended three years ago—by what he describes as “a very vague religious feeling,” which, infuriatingly, he doesn’t seem willing to expand upon. (This is also the case with most of his spiritual feelings.) These intense but vague feelings are somewhat embarrassing to him. They are deep and sensitive and the only clue to their existence used to be the punchy behavior that belied them (and thus confirmed them) on the surface.

Religion, in fact, plays not a vague, but an important part in his life. He has had a preoccupation with religious themes from the time he was at school. He doesn’t feel the absence of the presence of God so much as the presence of a God who is mainly absent. He is absolutely furious with God. He is enraged by what he sees as Malicious Behavior. However, notwithstanding this, he can identify easily with God’s Only Begotten. His brief portrayal of Christ on film, during the religious sketch in Good Evening, is the most convincing role he has played. He assumes the non-worldly gaze perfectly and there is no doubt in my mind that he is excellent world-saving material. On the other hand, in this world of opposites, he takes to the Devil with equal ease—as in our film, Bedazzled (a reworking of the Faust theme). Actually I think he is confused as to which is Which—or else he doesn’t really like to take sides. He wears the red devilish socks he wore in the film with the loyalty that John Wayne has for the hat and saddle he always uses in his Westerns. Peter is very proud of what his mother calls his “Devil’s eyebrow”—an eccentric peak on the right. His handwriting is that of Beelzebub—wayward, illegible even to himself. And at the core, as with all devils, there lies the soft sentimental center that can be moved to tears by a girl stage assistant in London who offered him a piece of her homemade cake; or by the mere thought of his two children, Lucy and Daisy; or by a photo of his new “dream house” in Hampstead, London (which, not surprisingly, backs onto the house he occupied some seven years ago during his first marriage). Peter is also moved by the thought of money.

Sometimes, during a performance of Good Evening, the thought of money descends on him as surreptitiously and quietly as those artificial miniature snowstorms that fall softly when you shake up your small bottle containing “A Winter View of London.” The blank stare that can alarmingly greet any one of my best-delivered lines falls into the category of what he has termed “mortgage acting.” Peter’s suddenly unseeing eyes reflect in their blue mists a brief and oversimplified calculation of his outstanding mortgage commitments, and a small breath of doom will momentarily anesthetize his features. The vibrations are so strong, I swear the majority of the audience feel for their small change. Although money is a paramount preoccupation with him, dollar bills sit unassumingly in his pocket like so many crumpled autumn leaves. When he produces them in a restaurant, limp and soggy, he regards them with a faint look of unrecognition and bemusement. He seems to be mutely asking somebody else to take charge of these defunct items—or, better still, to let him replace the notes quietly back in his pocket. He would prefer, he seems to semaphore, that the unsavory business of exchange and barter be taken over by those more skilled. To see him hand back a debt he has owed for three months is to see a man peel the skin off his face. His barely proffering arm moves arthritically to your outstretched palm. The noise of snapping springs is heard from his head as he parts finally with the precious bills— his body and soul, which are given to you like Communion wafers but rather less willingly.

Another of his manic passions is sport. He became unbearably au fait with American games, even to the point of dreaming, two weeks before the match, the correct half-time score (17-0) of the climactic game between the Miami Dolphins and the Vikings at the Super Bowl. That is dedication. At home in England, he shouts encouragement every Saturday afternoon of the season at the members of Tottenham Hotspurs Football Club. I accompanied Peter to one professional football match (my first and last such outing) and I was treated to a continuous barrage of fanfares from his mouth, some exhorting, some condemning, all obscene. He assumed uncannily the ribald tone of the other supporters, whose ensemble work, in moments of triumph or high derision, would rival any trained opera chorus with vigorous settings of such well-known texts as “What a Wanker” and “Nice one, Cyril.”

His brush with psychoanalysis was brief. A slight stumbling block to progress in that area has been his compulsion to lie to the analyst and then to despise and dismiss him for not seeing through these deceptions. It seems as if he is determined to put people to the test, however primitively and unfairly, and then, on their inevitable failure, to have his cynical view of people and the world confirmed. The philosophy here is, “Most people are ratbags”—which puts an unfair onus on his friends since any slight lapse from perfection condemns them to the same contempt.

It is hard to distinguish sometimes whether Peter is being playful or merely a berk. I think he maintains blurry outlines to give himself an exit, no matter what happens. His playfulness can slip gears easily and become charmless and childish. A desire to play becomes a desire to shock. It is born out of boredom. He can be like the flasher on the common who wants to see the woman indignant but has no interest in having her. On the other hand, the shock technique is a sometimes effective way of exploding superficialities in his relationships. Shock is never unreal. A shocked person is showing the truth at the moment of shock. I think Peter craves that glimpse of reality that will let him achieve a closeness that would have been inconceivable before.

Peter is a fundamentally lonely and, despite the occasional effort to convince you of the opposite, lovable man, touching and a bit touched. Frustratingly for me, he avoids his serious self like the plague, and if asked what he really wants to do in life, he replies with a twinkle, “I’m thinking of investing in North Korean real estate.” And if you ask what really lies at the center of his soul, he might tell you, “It’s not an asp.” You don’t get to learn much but you do get to laugh.

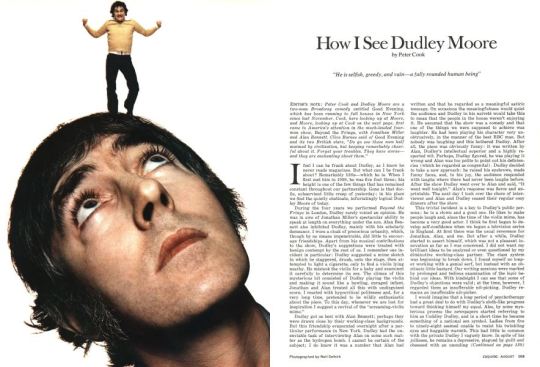

How I See Dudley Moore by Peter Cook, Esquire August 1 1974

I feel I can be frank about Dudley, as I know he never reads magazines. But what can I be frank about? Remarkably little—which he is. When I first met him in 1959, he was five foot three; his height is one of the few things that has remained constant throughout our partnership. Gone is that docile, subservient little creep of yesterday; in his place we find the quietly obstinate, infuriatingly logical Dudley Moore of today.

During the four years we performed Beyond the Fringe in London, Dudley rarely voiced an opinion. He was in awe of Jonathan Miller’s spectacular ability to speak at length on everything under the sun. Alan Bennett also inhibited Dudley, mainly with his scholarly demeanor. I wore a cloak of precocious urbanity, which, though by no means impenetrable, did little to encourage friendships. Apart from his musical contributions to the show, Dudley’s suggestions were treated with benign contempt by the rest of us. I remember one incident in particular: Dudley suggested a mime sketch in which he staggered, drunk, onto the stage, then attempted to light a cigarette, only to find a violin lying nearby. He mistook the violin for a baby and examined it carefully to determine its sex. The climax of this mysterious bit consisted of Dudley playing the violin and making it sound like a bawling, enraged infant. Jonathan and Alan treated all this with undisguised scorn. I reacted with hypocritical politeness and, for a very long time, pretended to be wildly enthusiastic about the piece. To this day, whenever we are lost for inspiration I suggest a revival of the “screaming-violin mime.”

Dudley got on best with Alan Bennett; perhaps they were drawn close by their working-class backgrounds. But this friendship evaporated overnight after a particular performance in New York. Dudley had the unenviable task of interviewing Alan on some such matter as the hydrogen bomb. I cannot be certain of the subject; I do know it was a number that Alan had written and that he regarded as a meaningful satiric message. On occasions the meaningfulness would quiet the audience and Dudley in his naïveté would take this to mean that the people in the house weren’t enjoying it. He assumed that the show was a comedy and that one of the things we were supposed to achieve was laughter. He had been playing his character very unobtrusively, in the manner of the best BBC man. But nobody was laughing and this bothered Dudley. After all, the piece was obviously funny: it was written by Alan, Dudley’s intellectual superior and a highly respected wit. Perhaps, Dudley figured, he was playing it wrong and Alan was too polite to point out his deficiencies (which he regarded as congenital). Dudley decided to take a new approach: he raised his eyebrows, made funny faces, and, to his joy, the audience responded with laughs where there had never been laughs before. After the show Dudley went over to Alan and said, “It went well tonight.” Alan’s response was fierce and unprintable. The next day I took over the chore of interviewer and Alan and Dudley ceased their regular cozy dinners after the show.

This trivial incident is a key to Dudley’s public persona: he is a clown and a good one. He likes to make people laugh and, since the time of the violin mime, has become a very good actor. I think he first began to develop self-confidence when we began a television series in England. At first there was the usual reverence for Jonathan, Alan, and me. But after a while, Dudley started to assert himself, which was not a pleasant innovation as far as I was concerned. I did not want my brilliant ideas to be analyzed or even questioned by my diminutive working-class partner. The class system was beginning to break down. I found myself no longer working with a genial serf, but instead with an obstinate little bastard. Our writing sessions were marked by prolonged and tedious examination of the logic behind our ideas. With hindsight I can see that some of Dudley’s objections were valid; at the time, however, I regarded them as insufferable nit-picking. Dudley remains an insufferable nit-picker.

I would imagine that a long period of psychotherapy had a great deal to do with Dudley’s sloth-like progress toward thinking himself my equal. Also, by some mysterious process the newspapers started referring to him as Cuddley Dudley, and in a short time he became something of a national sex symbol. Ladies from five to ninety-eight seemed unable to resist his twinkling eyes and huggable warmth. This had little in common with the private Dudley I vaguely know. In spite of his jolliness, he remains a depressive, plagued by guilt and obsessed with an unending search to find himself. It’s no use telling him to end this quest; he continues to believe he’s on the brink of a final discovery. God knows where he’ll turn next: group therapy, the Primal Scream, or, with a bit of bad luck, the Reverend Ike. He’s open to any new theory. I have this vision of Dudley on his deathbed, issuing a press statement saying, “I’m nearly there.”

I do not wish to knock psychotherapy; Dudley had every reason to need it. Born with a clubfoot, he spent a large part of his childhood in a hospital. At school he was a swot, much mocked by his confreres. Not until age thirteen did he discover that by making them laugh he could escape their hostility. Many comedians start this way. Dudley was obviously a bright child and his parents, though poor, encouraged him to study music. He won an organ scholarship to Magdalen college at Oxford and thereby left the milieu of Dagenham High School to join an allegedly intellectual elite. He was ill-equipped for this change. He still believes his mother and father slept in the same bed because they were too poor to afford two.

He was immensely insecure at Oxford. While I was trying to modify my grotesque upper-class accent to avoid embarrassing my working-class peers at Cambridge, Dudley was trying to eliminate his Cockney so he would get on with his social superiors. He eventually joined some theatre clubs and began to entertain, a self-protective practice he has yet to abandon, thank God. At this stage of his development he had a mind to become a choirmaster or music teacher. But after leaving Oxford he had the opportunity to play jazz in a North Country club, which he found dispiriting. Then he toured America with the Vic Lewis band. Finally the big break : he unwittingly became involved in a show that was scheduled to play four weeks at the Edinburgh festival, but went on to play four years in London, then two on Broadway. This was Beyond the Fringe. He was finally committed to show business and, whatever some psychotherapist may tell him, he will never become a choirmaster.

Now let’s get a little more personal. Over the years Dudley has learned certain things from me: he has become more greedy and more vain. On occasion Dudley will still say he is totally uninterested in money, but he conveniently ignores the fact that for fourteen years he has been earning a considerable income. He maintains that all he needs is a room, some food, and peace of mind. But, in fact, he has bought a Maserati, not the cheapest of cars, and a London house worth at least $150,000. His ex-wife Suzy lives in another house, worth, perhaps, even more. As old age creeps in he is becoming more and more beady about money. We jointly fired our respective agents last year; we resented that we had to give them ten percent of what we thought we could perfectly well negotiate ourselves. Hooray for psychotherapy! Dudley is selfish, greedy, and vain—a fully rounded human being.

But despite this realism, Dudley remains extremely naïve in some areas. He is receptive to any ideas offered to him by total strangers, or, worst of all, friends. He has had gallstones for years but it took an American doctor to figure it out. In the past he has visited homeopaths, herbalists, and God-knowswho to discover what’s wrong. He doesn’t smoke or drink very much. When he does, he’s likely to stand up on a table and make obscene speeches, going completely berserk. He is prone to every disease; once he went to a health club in England and, after one sauna, came down with pneumonia. He is physically perverse.

Dudley is a very tidy-minded person. He keeps an immensely accurate diary with every appointment written down. But he still manages to be late ninety percent of the time. He also maintains a diary about his thoughts and dreams. These are mainly concerned with bald cats and other disturbing images. Looking through a ten-year edition of these diaries, he was alarmed to discover that his private thoughts are much the same as they were in 1964. He is fascinated by other people’s problems and willing to spend hours listening to their neurotic woes.

In spite of his increasing greediness, he is capable of being generous to the point of lunacy: girl friends, gardeners, even strangers have been known to dip deeply into his pocket. For about a year he was in the clutches of a con man with an unending need of fifty pounds to “tide him over.” The man’s mother and sister were also in the act. I have no idea how many phony hip operations, train tickets, and funerals Dudley financed during this time. He finally broke himself of this relationship when the con man asked for funeral expenses for an aunt in Cardiff. Dudley remembered he had already paid for Aunt Ethel to be buried—at least twice—and came to the conclusion that a third ceremony was unnecessary.

Dudley Moore has no interest in politics whatsoever. His philosophy is that individuals should be nicer and more open with each other. He finds political argument bewildering and boring. Sport too he finds tedious, though we do have maniacal games of table tennis from time to time. His favorite reading is books on psychology, with a novel by someone like Virginia Woolf thrown in. He is an insomniac who refuses to take sleeping pills ; though immensely weight conscious, he’s given to wild midnight binges of chocolate cake, ice cream, and fizzy drinks. These episodes inspire his gallstones to frantic and painful dance.

Dudley is often asked whether he prefers comedy to music. His standard answer is that he likes both. Ever since I’ve known him he’s been talking about writing an opera. But he is more philosophical about it now: if it happens, fine, if not, why worry? In fact, he has at the moment no discernible plans for the future. He is quite happy performing Good Evening every night and doing little or nothing during the day.

Onstage Dudley is a perfectionist with a tremendous ability for physical comedy. I envy him for this. He is also an inveterate giggler. It only takes a sudden sneeze or strange laugh from the audience to set him off. He is prone to an occasional verbal slip. Twice he has greeted me onstage with the question, “How’s my filmous fame-star son?” My favorite moments have been his describing the death of my mother. My mother’s name in the show is Ada and I play the role of Roger, her famous film-star son. Quite often he will say, “I said to your mother, I said Roger. . . .” This inevitably leads to prolonged ad-libbing in which I accuse him of having called me Ada in the past and indeed of having crept into bed with me. This smutty business fills me with childish glee. Last week I pointed out another hidden danger in the script which I’m hoping he’ll stumble over: in the same scene he describes how a nurse fell five stories into the forecourt. I’m sure the day will come when she’ll fall four stories into the fives court.

Infantile things like this keep us both amused and I’m happy to say that, after fourteen years of working with him, Dudley still makes me laugh a great deal. During the two hours of the show I’m constantly on the verge of hysteria. I cannot imagine finding anyone else as much fun to work with. A banal tribute, but true.

#i was always afraid id lose this so here you go#the 70s were a bumpy road for them so its good to see these 2 talk abt eachother like this#''bumpy road'' is an euphemism lol#pc&dm

7 notes

·

View notes

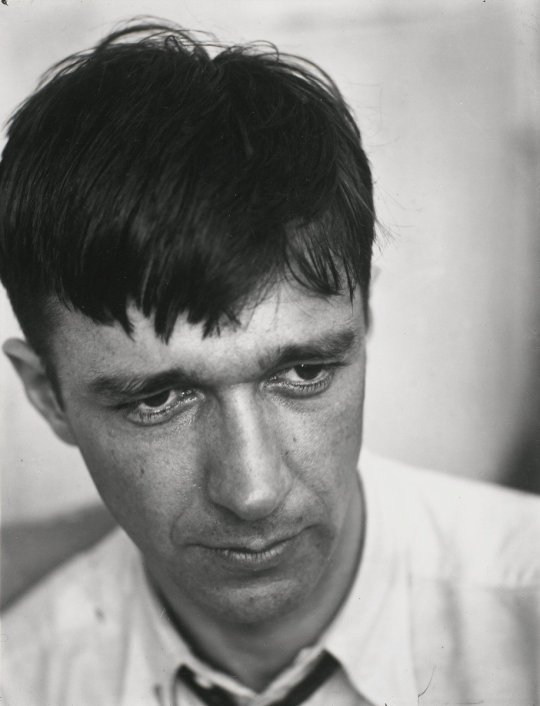

Photo

Self Portrait, Photo by Walker Evans, c. 1930-40s

160 notes

·

View notes

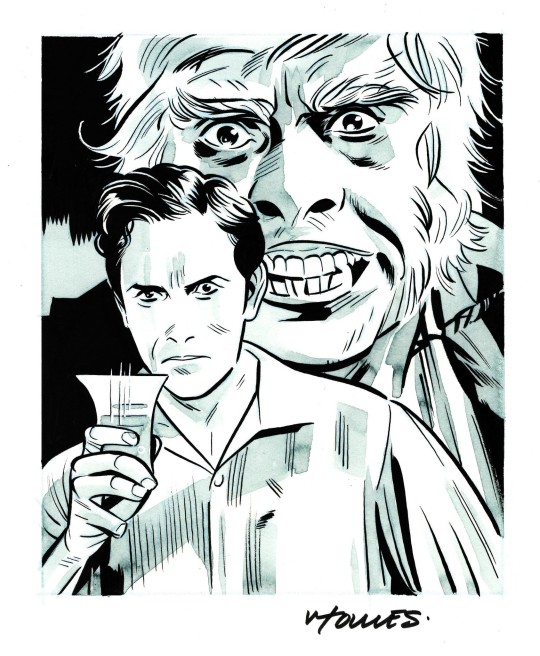

Text

Frederic March as Dr. Henry Jekyll and Mr. Hyde by Wilfredo Torres

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

John Lennon & Peter Cook in a sketch for the Christmas edition of Not Only... But Also | 27 November 1966

145 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“Journal d'un curé de campagne” (1950) by Robert Bresson

50 notes

·

View notes