Video

youtube

Left of Black with Hortense Spillers and Alexis Pauline Gumbs

I found this video to be really helpful in synthesizing M Archive: After the End of the World by Alexis Pauline Gumbs, though it’s not specifically about this text. I was particularly interested in Hortense Spillers and Gumbs talk about the writing process and theorize about writing a bit, discussing the physiological practice of writing, especially because we have read Spillers in this course as well. They also discuss the exigency behind their writing, talking about how politics motivate their writing. Gumbs discusses community and intimacy as well, reminding me of last week’s text, Care Work: Dreaming Disability Justice.

On an unrelated note, I don’t know if anyone has read Our Sister Killjoy, but it’s an experimental text that discusses themes of colonialism and black diaspora and has a very similar reading experience--I think it would be interesting to read these side-by-side.

1 note

·

View note

Text

In the first section of M Archive. After the End of the World by Alexis Pauline Gumbs, there are descriptions of how humans and non-human animals can relate to each other and how humans have a lot to understand and learn from non-human animals. One passage says:

in the end it was triangulation. they specified how different they were from each other until they could extrapolate and find god.in the end it was a false triangle. they tried to chart god and kept getting back to themselves. they tried to chart each other and kept getting back to themselves. they tried to chart themselves, but how could that be objective? (pg. 21-22)

Here, I think of the Great Chain of Being, a Christian decree from God that declared a hierarchical structure among all beings. The Great Chain of Being placed Gods at the top, then humans, mammals and human-like animals, other animals, plants, and minerals at the bottom. This Western Christian hierarchical philosophy was used to then distinguish between White people and Black and Native people by categorizing White people with Gods and Black and Native people with animals (Wynter, 2003). Gump asks us to consider alternative ways of relating to other humans, non-human animals, plants, and the earth.

0 notes

Text

A Disability Reality During COVID-19

https://www.sinsinvalid.org/news-1/2020/3/19/social-distancing-and-crip-survival-a-disability-centered-response-to-covid-19

The pervasiveness of ableist dialogue dominates newspapers, social media posts, and news outlets in their calls to “social distance,” “wash your hands,” and “shelter-in-place.” The assumption of now limited capabilities is hitting the able-bodied communities hard, as if the reality of this new world is somehow limiting. The truth of it is: this new world amidst COVID-19 is limiting. However, for many, this world already was. Social movements, crip theorists, and disability advocates have put the call out for accessibility changes, receiving a silent response. In uncertain times like COVID-19, when protocols are further hinder and destabilize the lives of disabled persons in many ways, there still remains a call for action with a silent response. What we need is a collective care approach, rather than a self-care model. Self-care puts the burden of meeting ones needs on the self, particularly the disabled self already trying to figure out survival in spaces and times defined by ableist priorities. Collective care argues for accommodation, knee-jerk support for those who need time, space, and creative adaptability to be productive and successful. We need radical, creative solutions to meeting the needs of those who have been left to fend for themselves. In the time of COVID-19, we need to move beyond the self-care mode of thought and move toward a collective care scheme of community organizing for better access, support, and response to the needs of the disabled.

To learn more, click here: https://www.queerfutures.com/queercrip

0 notes

Text

Whats happens after Covid-19?

https://www.vox.com/future-perfect/2020/3/24/21188779/mutual-aid-coronavirus-covid-19-volunteering

https://inthesetimes.com/article/22427/disabled-queer-activists-isolation-mutual-aid-bay-area-covid-19

As we experience a global pandemic and people are ordered to remain at home, people are taking up mutual aid care models that might previously be labeled radical and would probably be ignored. Now, we have enormous lists of mutual aid networks that span the country. Why is it that the way we choose to have relationships with each other changes during a pandemic? Mutual aid is not the only example of this. Disabled folks have been asking about the possibilities of working from home for a while, and these propositions have been mostly dismissed and denied for reasons such as inconveniency or impossibility for years. However, now, we are seeing that working from home is totally possible. The list of our changed behavior continues with government aid, eviction suspensions, and a diminished harmful interaction on our environment. If these ways of living work during a global pandemic, then shouldn’t we practice them in non-crisis situations as well? People have said that after the pandemic life will never go back to how we knew it before, but how do we make that a positive change rather than an escalation of surveillance, racism, and distrust?

0 notes

Photo

Kimiko Yoshida is a Japanese artist that creates portraits where he blends in with the background and the objects around her.

She says that her project is not about identity. Instead, she calls it a "ceremony of disappearance."

Yoshida blends in with the background and objects around her in all of her monochromatic portraits, even the ones with ornate, elaborate decorations. Her face becomes part of these ornaments, and it becomes hard to tell where the person ends and where the background/objects start.

Anne Cheng writes this about the ornamentalism of Asian women: "Let us think through, rather than shy away from, that intractable intimacy between being a person and being a thing."

I think we can view Yoshida's art through this theory of ornamentalism. Her portraits force you to ask yourself where the line is drawn between the person and the object, if there even is one.

0 notes

Text

Ornamentalism

Anne Anlin Cheng’s Ornamentalism works to establish an Asiatic feminist theory, that to my knowledge, is the first of its kind. Cheng proposes the theory of Ornamentalism, and this enhances our ability to think of racialized and gendered persons outside of flesh. To crudely summarize, I interpreted Orientalism to be about understanding how things become people, rather than our usual understanding of people becoming things. Ornamentalism differs from Orientalism as it maintains that objects are what make up the yellow woman in Western society. What Cheng’s work provides is a broader understanding (or, for me, a brand-new understanding) of Asian women/femininity in the Western context. Ornamentalism makes it possible for us to understand just how naturalized a perception of the yellow women as and through objects with racial meaning has become.

While this text is conceptually challenging, I thoroughly enjoyed it and would absolutely recommend it. Not only does this text provide a much-needed context to understand the yellow women’s conception and experience, this piece can be used and applied to other theory making and feminist work. This work does more than introduce a new theory, this piece allows us to rethink how we conceptualize humanness, objectness, agency, and more. In short, this work has the power to completely alter our worldview.

0 notes

Video

youtube

The concept of intersectionality was coined by scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw (1993) to conceptualize that social identities, in relation to infrastructures of oppression, discrimination, or supremacy, and a myriad of group identities intersect to cultivate an entity that differentiates itself from the sectional identities. It’s nearly impossible to discuss Black Feminism without the consideration of intersectionality. The ideology behind Black Feminism is essentially a way of life that requires an intense comprehension of the intersectionality of race and gender and a present and passionate evidence of self. In framing intersectionality, Crenshaw (2014) notes that “Within any power system there is always a moment - and sometimes it lasts a century - of resistance to the implications of that. So we shouldn’t really be surprised about it.”

According to May (2015), intersectionality exposes how traditional approaches to inequality, including feminist, civil rights, and liberal rights models, tend to: “mistakenly rely on single-axis modes of analysis and redress; deny or obscure multiplicity or compoundedness; and depend upon the very systems of privilege they seek to challenge” (156). As Black women, we are often subjected to scenarios and instances where we are expected to choose between our intersectional identities. Some instances it’s choosing our Blackness over our gender when fighting for Black Lives Matter. Or choosing our gender over our Blackness when fighting with other women. It’s ironic that we are able to embrace all of our identities yet all of our oppressions are a result of our identities working in unison. Puar (2012) recognizes this as a tension between two opposing forces.

The video above illustrates, as the title suggests, what it means to be Black and Woman and simply exist.

References

Crenshaw, Kimberlé. “Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color.” Stanford Law Review. 43, no. 6 (1993): 1241-1299.

Crenshaw, Kimberlè. “Kimberlé Crenshaw on Intersectionality ‘I wanted to come up with an everyday metaphor that anyone could use’”. Modified 2014. https://www.newstatesman.com/.

May, Vivian. Pursuing Intersectionality, Unsettling Dominant Imaginaries. New York: Routledge, 2015.

Puar, Jasbir K. “I Would Rather Be a Cyborg than a Goddess: Becoming-Intersectional in Assemblage Theory.” PhiloSOPHIA. 2, no. 1 (2012): 49-66.

0 notes

Text

Care Work and Disability Justice: A Call to Action

Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha’s Care Work: Dreaming Disability Justice (2018) is a striking book about what many do not see - or, rather, care to not see both in ourselves and in the world ablest thought has created. Care work thinking is a radical approach to questioning our natural assumptions about the privileges many harbor about our modes of imagining inclusivity and accessibility. Care work challenges us to reconsider our positionality and its entailed assumptions about our capacity to think, feel, and do on a daily basis, emphasizing the importance of taking into account how our thinking, reasoning, and imagining is inherently exclusionary because we take our abilities as natural and universal - rather than considering them components of our own conscious experience. Piepzna-Samarasinha’s discussion of care webs asks us to imagine ourselves in such a way that we require assistance to do what many do unencumbered on a daily basis. The author pushes us to envision how our life would look like if we had to account for these challenges and how such challenges present significant daily obstacles to living. Growing up as a child of a parent who faced many of these obstacles, especially access to quality health care and treatment, it is a terrifyingly real situation that needs to change. Our world is not built to include but rather exclude and disparage anyone who does not abide by the logics of bootstrapping. One of the main reasons that has led to our present situation lies in our dependence on the eye: I often point to the adage, “out of sight, out of mind” to encapsulate why these conditions of exclusion are neglected. Piepzna-Samarasinha challenges us to

Stop forgetting about disability and access. Read some of the many brilliant, made-by-disabled-people access guides out there. Normalize access and disability. Learn about disabled cultures and histories. Look at histories of disability in your own family and communities. Ask how you are fighting ableism in every campaign you do. Don’t forget about us. Realize you are or will be us. (Piepzna-Samarasinha 2018)

To add further to this rousing call to action, I have included an interview by Mia Mingus on disability justice and what it means as a political framework.

Disability Justice - Mia Mingus (interview clip)

(Here is the full interview.)

0 notes

Photo

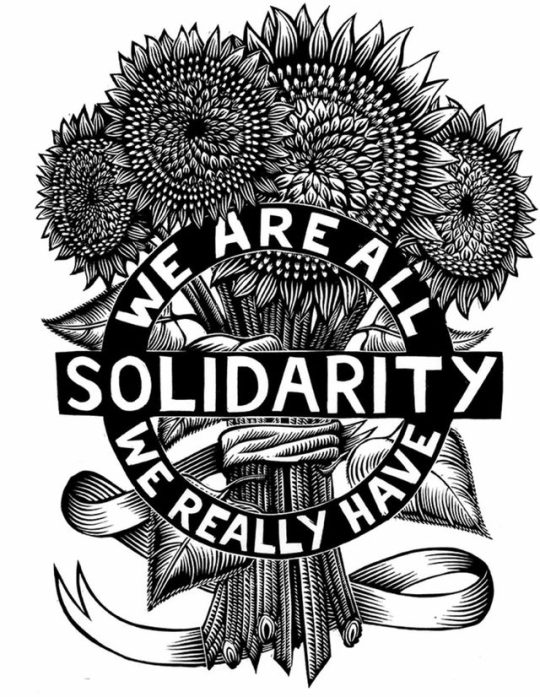

This lovely poster above was made by Roger Peet for Justseeds, a worker-owned, decentralized artist collective.

It is no secret that the current state of affairs are grim. Between the pandemic and the current political climate, especially with Bernie suspending his campaign, things are not exactly looking up right now. In these times, it becomes even more paramount that we look to our community and each other for support. Many places are starting mutual aid groups to help folks through this time, Gainesville included (Gainesville’s COVID-19 Mutual Aid). Keep checking in on each other; keep offering support and asking for support in the ways that are right for you. Care work and solidarity are needed now more than ever.

0 notes

Text

Ornamentalism and Orientalism

In Ornamentalism, Anne Anlin Cheng theorizes about the “yellow woman”, laying bare the underlying logics of ornamentalism within Western discourse. She distinguishes her approach from that of Edward Said’s notable project, Orientalism: “While primitivism rehearses the rhetoric of ineluctable flesh, Orientalism, by contrast, relies on a decorative grammar, a phantasmic corporeal syntax that is artificial and layered” (Cheng, 5-6). Moreover, she contends, “Orientalism is a critique, ornamentalism a theory of being” (Cheng, 18). To better understand Cheng’s argument, it is important to clearly articulate a visual explanation of Orientalism and why such is relevant to making sense of her work. An understanding of Orientalism is imperative as Cheng posits a strong interpretive nuance that simultaneously troubles and opens Said’s critique. In Cheng’s work, we return to the problem of representation and how certain representations repeat stereotypical tropes that essentialize groups of people. These tropes are often deployed in popular culture as a way to reproduce their own currency, continuously circulating seemingly new images that play on these old tropes that function to re-entrench differences through notions of otherness (“exotic”, “hedonistic”, “lewd”, etc.). Cheng contributes to this dialogue by exploring, examining, and dismantling representations of the Asiatic "yellow woman" and constructing a much-needed theoretical perspective. She explains that “Simultaneously consecrated and desecrated as an inherently aesthetic object, the yellow woman calls for a theorization of persons and things that considers a human ontology inextricable from synthetic extensions, art, and commodity” (Cheng, 2). Thus, to grasp the importance of her efforts, a brief foray into why dialogues around Orientalism are as relevant now as when Said leveled his challenge:

Why Arabs And Muslims Aren't Exotic | AJ+

Cheng’s work is instructive here because she provides us with ways of more effectively thinking and theorizing about representation and its distinctive use of ornamentation. When we see the images of an “exotic” world, the items within are coded in a certain way that devalues and commodifies otherness. However, following Cheng’s argument, the logics of ornamentalism expose the messy logics of the legal, popular, aesthetic, social, cultural, and political realms, providing a new approach to making sense of the critique of Orientalism and primitivism, on the one hand, and the thinking about the broader project of ornamentalism, on the other.

Cheng, Anne Anlin. 2019. Ornamentalism. New York: New York University Press.

Said, Edward W. 1979. Orientalism. Vintage Books.

0 notes

Text

Object Relations/Desire

In Juana María Rodríguez, “Latina Sexual Fantasies: The Remix” Rodríguez, takes us on a tour of “normative feminine sexuality” and its direct relationship with whiteness. While I greatly enjoyed Rodríguez’s work in its entirety, there were a few points that particularly stuck with me.

First, the point that pornography is often compared to art as a binary touched me. This conversation reminded me of Adrienne Rich’s work “Compulsory Heterosexuality and Lesbian Existence” and its critiques of pornography. While Rodríguez believes that art and porn are not on a binary but a spectrum, I had never thought of how porn and art are generally placed in opposition. This point lead me to think more deeply about another conversation that Rodríguez has. Rodríguez also states that pornography is often used as a scapegoat for our frustrations, her note that pornography is “a monster we know how to hate” rang exceedingly true for me personally. I have found myself upset with pornography in the past, for its problematic portrayals, but upon deeper consideration Rodríguez is correct to state that I am actually frustrated with the larger systems of power that pornography mimics and reifies.

Similarly, I was struck by Rodríguez’s discussion of her sister’s work. Rodríguez’s work reminds us of how sex sells, but more, how advertising sends messages to us of what is desirable. Like porn, advertising reifies larger structures of power, in banal ways, and this impacts young girls- especially young Latina or young black girls.

Lastly, the focus of Rodríguez’ work, on how being a racialized subject impacts pleasure and livelihood for Latin@s, is imperative to consider in our feminist work. The complexity of desire and submission, especially for Latin@s who must submit to the state, or Latinas who are expected to submit to the state (and their lovers) is a conversation that needs to be had. Rodríguez’s work is meant to push us to think about our “erotic attachments to power” and how our sexual fantasies can exemplify that attachment.

To put simply, this piece made it possible for me to think about racialized sexual fantasies in new and complex ways. While prior to this my feelings toward porn and explicit sexualization were complicated, this work has made the relationship more so.

0 notes

Text

Artist Spotlight: Toyin Ojih Odutola

I wanted to draw attention to the cover art for the book Black Feminism Reimagined: After Intersectionality that was created by artist Toyin Ojih Odutola titled The Uncertainty Principle (2014). Odutola was born in 1985 in Nigeria but relocated to Alabama in 1994 due to her father getting a new teaching position, this move would later influence her work. Ojih Odutola earned her BA from the University of Alabama in Huntsville and her MFA from California College of the Arts in San Francisco.

She creates multimedia drawings on various surfaces investigating the limits of representation while engaging with eclectic modes of storytelling. She has shown in the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Brooklyn Museum, and the Menil Collection, in Houston, among others and has permanent collections in the Museum of Modern Art, Whitney Museum of American Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Baltimore Museum of Art, New Orleans Museum of Art, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Princeton University Art Museum, and the National Museum of African Art (from website).

I found that some of her work and positions have been criticized, much like the positions Nash takes in the reading from last week. Some criticism comes from her art depicting wealth as the solution to black problems which she defends in an interview with vogue:

“I understand that this is a significant part of black life around the globe,” she continues, “but if all we’re known for is our pain and our struggle, what does that say? I don’t want young people to feel that is the only way they can talk about themselves, through that lens. Black stories can be ridiculous. Black stories can be silly. They can be problematic. They can be mediocre and remarkable. They can be boring. Can we have that privilege now? Instead of having to be exceptional all the time? That was the aim of this whole saga—just to see that.”

Full interview: https://www.vogue.com/article/toyin-ojih-odutola-interview-vogue-august-2018

0 notes

Video

youtube

Scholar Jennifer C. Nash claims, that "there is a single affect that has come to mark contemporary academic black feminist practice: defensiveness" (3). Today, we are seeing an increase in feminist scholarship and ideologies on both a social and institutional level. Specifically, the prevalence of academic sectors such as Women's Studies, Gender Studies, Ethnic Studies, etc. has increased dramatically. However, in their efforts to overcome past exclusions of marginalized experiences, the corporate university has created a new strand of exclusionary behavior- one that writes the black out of black feminism.

This video portrays the poetry of black feminist Jillian Christmas. Exemplifying Nash's defensive tone, Christmas speaks to the current-day intersectionality wars. Black woman are included in feminism without having their historical roots recognized. Black woman feel obligated to give their stores for others to consume (for social or institutional progress) without having their trauma, personal experiences, or emotional connections acknowledged. Black women are expected to give their "blackest weather," their dark and brutal realities; but, at what cost? Why are black women's stories sought to be included but not in the right ways? Christmas' poem reminds us that we cannot use blackness as an aid to progress if we define their experience's as martyr's for an intersectional/diverse agenda.

"It is, though, ultimately a dangerous form of agency, one that traps black feminism, and black feminists, rather than liberating us, by locking black feminists into the intersectionality wars rather than liberating us from those battles" (Nash, 27).

We must reimagine what can happen when we move beyond intersectionality. In what ways must we truly look back in order to progress?

Nash, Jennifer C. Black Feminism Reimagined: After Intersectionality. Duke University Press, 2018.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Andrew Norris - Blog Post #1

I really enjoyed Them Goon Rules because of its relatable language but also its revolutionary points the author made. I really loved getting a glimpse into the authors perspective and found a lot of the poverty references very relatable to growing up in rural Appalachia - especially how they would encourage their children to “never forget”. This not forgetting once’s prior circumstances is very common in poor families that value their circumstances so much that it is threaded into their identities.

My first initial thought of reading the into part of Them Goon Rules is in the way Maquis Bey describes fugitivity and its contrast to the way Snorton described it in Black on Both Sides. I felt that Maquis Bey had a clarity in the way fugitivity was explained that I thought was missing from Snorton that left me with a bit of unclear resolution of the concept - I would probably had benefited more from reading this book first before Snorton. I think one of the ways this book achieved a relatable, yet powerful language was in the references to popular culture and music (in the reference to Lil Wayne) and in the personal anecdotes of experiences the author had in captivity from police. The relationship of power and authority as well as Law being distinct from Justice were also helping me shape a clearer understanding of this concept.

My second thought going into this book was a possible connection that fugitivity has to the “Be Gay, Do Crime” movement/viral phrase that I found within the queer Instagram community. I found a quote going over a possible interpretation of the phrase could mean as there is still some debate as to its origins:

“Crime is the word used to describe the survival tactics many marginalized people must use to survive under capitalism, one reason queers are among those most likely to be locked up. Especially if you also happen to be trans, PoC, sex worker (especially post-SESTA/FOSTA) or just any identifiable type of lower caste.

‘So I guess the slogan means we’re done negotiating with mainstream gays over respectability. We realized being a gay criminal is the coolest thing you could be and war on bourgeois morality is the coolest thing you could do.’

https://www.gaystarnews.com/article/what-does-be-gay-do-crime-mean/

0 notes

Photo

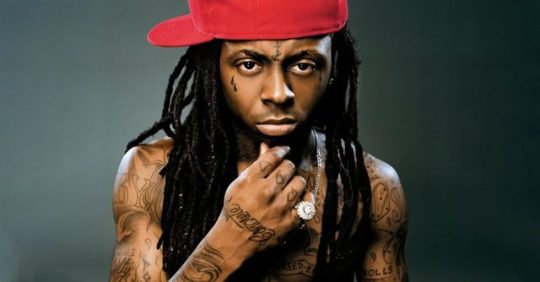

What do you see when you look at this photo? You might know who it is. But do you know what it is? It is a display of fugitive Blackness.

A fugitive is related to capture; this captivity being in hands of hegemonic, normative, law. But what happens when the fugitive exceeds captivity? What happens when captivity is refused?

Tell the coppers “hahahaha” you can’t catch ’em, you can’t stop ’em..

I go by them goon rules, if you can’t beat ’em, then you pop ’em

-Lil Wayne, "A Milli"

Lil Wayne exemplifies Marquis Bey's declaration that "to 'go by them goon rules' is a praxis of unruliness in the sense that the deviancy cast upon those who undermine systemic rule is mobilized in service of the deviant" (16).

"Like racism the idea and image of a Thug happens- indeed, thugs happen, they are a phenomenological occurrence- in the gap between appearance and the perception of difference, streamlined through a history that has emblematized criminality through a proximity to Blackness" (Bey, 37).

So I ask, do you see less value in this photo? Do you see a criminal? First, do you even see a human?

Bey, Marquis. Them Goon Rules: Fugitive Essays on Radical Black Feminism. University of Arizona Press, 2019.

0 notes

Text

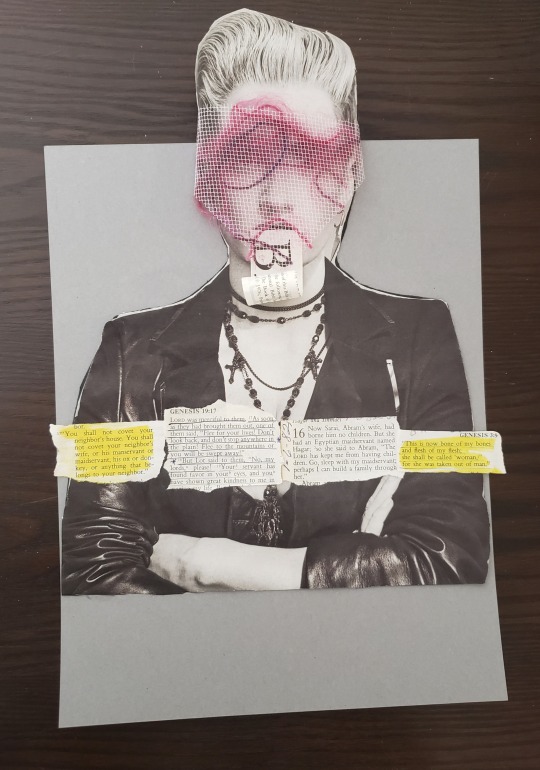

"Bible Gagged" - a collage piece on the resistance to the objectivity, domination, commodification, and oppression of female bodies by religious doctrine.

0 notes

Video

youtube

Snorton (2017) asks "What counts as black history and what role do the conditions of slavery and capitalism play in the fungibility (or interchangeability) of transness and blackness"? Erasure of one translates to erasure of all. Even in the study of queer folk (coupled with women's studies), Keegan (2018) suggests that "partnerships struck through sexual subordination models, W(omen), L(esbians), and G(ays) will need T(rans people) to stay quiet to retain their coherence as categories based on the legibility of gender and sex". No Black and/or queer body means more than another. Because of this and the fact that it's #BlackHistoryMonth, I decided to post a video that celebrates Black Trans Beauty. Because there is enough marginalization, racism, and erasure in this world.

1 note

·

View note