Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Apparently "the high risk will protect themselves" overrides the Hippocratic oath.

108 notes

·

View notes

Text

Also preserved on our archive

Summary: A new study reveals that 12-18 months after hospitalization for COVID-19, patients show significant cognitive decline comparable to 20 years of aging. MRI scans and blood tests also show brain injury markers and reduced brain volume in these patients. The findings suggest that COVID-19 has lasting effects on brain health, even in those without neurological complications.

Key Facts:

COVID-related cognitive decline equals about 20 years of normal aging. Brain scans show reduced volume and injury in key areas after COVID-19. Both neurological and non-neurological patients experienced cognitive deficits. Source: University of Liverpool

New steps have been taken towards a better understanding of the immediate and long-term impact of COVID-19 on the brain in the UK’s largest study to date.

Published in Nature Medicine, the study from researchers led by the University of Liverpool alongside King’s College London and the University of Cambridge as part of the COVID-CNS Consortium shows that 12-18 months after hospitalisation due to COVID-19, patients have worse cognitive function than matched control participants.

Importantly, these findings correlate with reduced brain volume in key areas on MRI scans as well as evidence of abnormally high levels of brain injury proteins in the blood.

Strikingly, the post-COVID cognitive deficits seen in this study were equivalent to twenty years of normal ageing. It is important to emphasise that these were patients who had experienced COVID, requiring hospitalisation, and these results shouldn’t be too widely generalised to all people with lived experience of COVID.

However, the scale of deficit in all the cognitive skills tested, and the links to brain injury in the brain scans and blood tests, provide the clearest evidence to date that COVID can have significant impacts on brain and mind health long after recovery from respiratory problems.

The work forms part of the University of Liverpool’s COVID-19 Clinical Neuroscience Study (COVID-CNS), which addresses the critical need to understand the biological causes and long-term outcomes of neurological and neuropsychiatric complications in hospitalised COVID-19 patients.

Study author Dr Greta Wood from the University of Liverpool said: “After hospitalisation with COVID-19 many people report ongoing cognitive symptoms often termed ‘brain fog’.

“However, it has been unclear as to whether there is objective evidence of cognitive impairment and, if so, is there any biological evidence of brain injury; and most importantly if patients recover over time.

“In this latest research, we studied 351 COVID-19 patients who required hospitalisation with and without new neurological complications.

“We found that both those with and without acute neurological complications of COVID-19 had worse cognition than would be expected for their age, sex and level of education, based on 3,000 control subjects.”

Corresponding author Professor Benedict Michael, Professor of Neuroscience at the University of Liverpool said: “COVID-19 is not a condition simply of the lung. Often those patients who are most severely affected are the ones who have brain complications.

“These findings indicate that hospitalisation with COVID-19 can lead to global, objectively measurable cognitive deficits that can be identified even 12-18 months after hospitalisation.

“These persistent cognitive deficits were present in those hospitalised both with and without clinical neurological complications, indicating that COVID-19 alone can cause cognitive impairment without a neurological diagnosis having been made.

“The association with brain cell injury biomarkers in blood and reduced volume of brain regions on MRI indicates that there may be measurable biological mechanisms underpinning this.

“Now our group is working to understand whether the mechanisms that we have identified in COVID-19 may also be responsible for similar findings in other severe infections, such as influenza.”

Professor Gerome Breen from King’s College London said: “Long term research is now vital to determine how these patients recover or who might worsen and to establish if this in unique to COVID-19 or a common brain injury with other infections.

“Significantly our work can help guide the development of both similar studies in those with Long-COVID who often have much milder respiratory symptoms and also report cognitive symptoms such as ‘brain fog’ and also to develop therapeutic strategies.”

More about COVID-CNS

The COVID-19 Clinical Neuroscience Study (COVID-CNS) is a £2.3m UKRI study jointly led by researchers at the University of Liverpool and King’s College London. Acute neurological and neuropsychiatric complications of COVID-19 affect up to 20-30% of hospitalised patients.

Researchers are studying the acute neurological and neuropsychiatric effects of infection, the long-term clinical and cognitive outcomes, and crucially determining the underlying biological processes driving this through better understanding of brain injury, immune responses and genetic risk factors.

Funding: This publication was funded by the UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) grant COVID-CNS and is supported through the national NIHR BioResource and the NIHR Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre.

We thank NIHR BioResource team and patient volunteers for their participation and the Patient and Public Involvement Panel who guided each stage.

About this cognition, COVID, and aging research news Author: Jennifer Morgan Source: University of Liverpool Contact: Jennifer Morgan – University of Liverpool Image: The image is credited to Neuroscience News

Original Research: Closed access. “Post-hospitalisation COVID-19 cognitive deficits at one year are global and associated with elevated brain injury markers and grey matter volume reduction” by Greta Wood et al. Nature Medicine

Abstract

Post-hospitalisation COVID-19 cognitive deficits at one year are global and associated with elevated brain injury markers and grey matter volume reduction

The spectrum, pathophysiology, and recovery trajectory of persistent post-COVID-19 cognitive deficits are unknown, limiting our ability to develop prevention and treatment strategies.

We report the one-year cognitive, serum biomarker, and neuroimaging findings from a prospective, national study of cognition in 351 COVID-19 patients who had required hospitalisation, compared to 2,927 normative matched controls.

Cognitive deficits were global and associated with elevated brain injury markers, and reduced anterior cingulate cortex volume one year after COVID-19. The severity of the initial infective insult, post-acute psychiatric symptoms, and a history of encephalopathy were associated with greatest deficits.

There was strong concordance between subjective and objective cognitive deficits. Longitudinal follow-up in 106 patients demonstrated a trend toward recovery.

Together, these findings support the hypothesis that brain injury in moderate to severe COVID-19 may be immune-mediated, and should guide the development of therapeutic strategies.

Study Link: www.nature.com/articles/s41591-024-03309-8 (PAYWALLED but I have a copy I can share. Contact me on Tumblr.)

156 notes

·

View notes

Text

Reference preserved in our archive

Abstract Background: COVID-19 emerged in December 2019 and rapidly became a global pandemic. It has since been associated with the progression of various endocrine disorders, including thyroid disease. The long-term effects of this interplay have yet to be explored. This review explores the relationship between COVID-19 and thyroid diseases, emphasizing thyroid gland function and the clinical implications for managing thyroid disorders in infected individuals.

Objectives: This narrative review intends to provide insight into the scope of research that future clinical studies may aim to address regarding the long-term effects of COVID-19 infection on thyroid health.

Methods: Keywords including “thyroid disease”, “COVID-19”, and “long-term” were used to search PubMed and Google Scholar for updated and relevant clinical research.

Results: COVID-19 affects the thyroid gland multifacetedly and includes direct viral invasion, immune-mediated damage, and hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis disruption. Approximately 15% of COVID-19 patients experience thyroid dysfunction, which can present as thyrotoxicosis, hypothyroidism, or non-thyroidal illness syndrome (NTI). Noteworthy findings include inflammatory thyroiditis. Long-term effects, including those observed in children, include persistent hypothyroidism and exacerbated pre-existing thyroid-autoimmune conditions. Management of thyroid disorders in COVID-19 patients requires consideration: anti-thyroid drug (ATD) therapy used to treat hyperthyroidism in COVID-19 patients may need adjustment to prevent immunosuppression. Radioactive iodine (ROI) alternatives and interleukin-6 (IL-6) receptor antagonists could offer potential benefits and should be further explored.

Conclusion: Longitudinal follow-ups post-COVID-19 for patients with new and pre-existing thyroid disorders can improve disease outcomes. In addition, pathophysiological research on thyroid dysfunction in COVID-19 may help develop strategies to prevent and alleviate thyroid gland abnormalities post-COVID-19.

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Just a cold" that puts holes in your mitochondria doctor's can't see.

11K notes

·

View notes

Text

Guess who has their sewing machine oiled and working, and wants to create another Covid-themed art series?

Might do a poll on what to call this series, as I work through my own thoughts (and try and get my sewing cursive looking readable!)

[Image Descriptiom of two black KN95 face masks with white straight-stitch sewing in cursive words, on top of them. The first mask has the words “this isn’t normal” and the second mask has the word “this”. End ID]

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Patients With Long-COVID Show Abnormal Lung Perfusion Despite Normal CT Scans - Published Sept 12, 2024

VIENNA — Some patients who had mild COVID-19 infection during the first wave of the pandemic and continued to experience postinfection symptoms for at least 12 months after infection present abnormal perfusion despite showing normal CT scans. Researchers at the European Respiratory Society (ERS) 2024 International Congress called for more research to be done in this space to understand the underlying mechanism of the abnormalities observed and to find possible treatment options for this cohort of patients.

Laura Price, MD, PhD, a consultant respiratory physician at Royal Brompton Hospital and an honorary clinical senior lecturer at Imperial College London, London, told Medscape Medical News that this cohort of patients shows symptoms that seem to correlate with a pulmonary microangiopathy phenotype.

"Our clinics in the UK and around the world are full of people with long-COVID, persisting breathlessness, and fatigue. But it has been hard for people to put the finger on why patients experience these symptoms still," Timothy Hinks, associate professor and Wellcome Trust Career Development fellow at the Nuffield Department of Medicine, NIHR Oxford Biomedical Research Centre senior research fellow, and honorary consultant at Oxford Special Airway Service at Oxford University Hospitals, England, who was not involved in the study, told Medscape Medical News.

The Study Researchers at Imperial College London recruited 41 patients who experienced persistent post-COVID-19 infection symptoms, such as breathlessness and fatigue, but normal CT scans after a mild COVID-19 infection that did not require hospitalization. Those with pulmonary emboli or interstitial lung disease were excluded. The cohort was predominantly female (87.8%) and nonsmokers (85%), with a mean age of 44.7 years. They were assessed over 1 year after the initial infection.

Exercise intolerance was the predominant symptom, affecting 95.1% of the group. A significant proportion (46.3%) presented with myopericarditis, while a smaller subset (n = 5) exhibited dysautonomia. Echocardiography did not reveal pulmonary hypertension. Laboratory findings showed elevated angiotensin-converting enzyme and antiphospholipid antibodies. "These patients are young, female, nonsmokers, and previously healthy. This is not what you would expect to see," Price said. Baseline pulmonary function tests showed preserved spirometry with forced expiratory volume in 1 second and forced vital capacity above 100% predicted. However, diffusion capacity was impaired, with a mean diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide (DLCO) of 74.7%. The carbon monoxide transfer coefficient (KCO) and alveolar volume were also mildly reduced. Oxygen saturation was within normal limits.

These abnormalities were through advanced imaging techniques like dual-energy CT scans and ventilation-perfusion scans. These tests revealed a non-segmental and "patchy" perfusion abnormality in the upper lungs, suggesting that the problem was vascular, Price explained.

Cardiopulmonary exercise testing revealed further abnormalities in 41% of patients. Peak oxygen uptake was slightly reduced, and a significant proportion of patients showed elevated alveolar-arterial gradient and dead space ventilation during peak exercise, suggesting a ventilation-perfusion mismatch.

Over time, there was a statistically significant improvement in DLCO, from 70.4% to 74.4%, suggesting some degree of recovery in lung function. However, DLCO values did not return to normal. The KCO also improved from 71.9% to 74.4%, though this change did not reach statistical significance. Most patients (n = 26) were treated with apixaban, potentially contributing to the observed improvement in gas transfer parameters, Price said.

The researchers identified a distinct phenotype of patients with persistent post-COVID-19 infection symptoms characterized by abnormal lung perfusion and reduced gas diffusion capacity, even when CT scans appear normal. Price explains that this pulmonary microangiopathy may explain the persistent symptoms. However, questions remain about the underlying mechanisms, potential treatments, and long-term outcomes for this patient population.

Causes and Treatments Remain a Mystery Previous studies have suggested that COVID-19 causes endothelial dysfunction, which could affect the small blood vessels in the lungs. Other viral infections, such as HIV, have also been shown to cause endothelial dysfunction. However, researchers don't fully understand how this process plays out in patients with COVID-19.

"It is possible these patients have had inflammation insults that have damaged the pulmonary vascular endothelium, which predisposes them to either clotting at a microscopic level or ongoing inflammation," said Hinks.

Some patients (10 out of 41) in the cohort studied by the Imperial College London's researchers presented with Raynaud syndrome, which might suggest a physiological link, Hinks explains. "Raynaud's is a condition of vascular control or dysregulation, and potentially, there could be a common factor contributing to both breathlessness and Raynaud's."

He said there is an encouraging signal that these patients improve over time, but their recovery might be more complex and lengthy than for other patients. "This cohort will gradually get better. But it raises questions and gives a point that there is a true physiological deficit in some people with long-COVID."

Price encouraged physicians to look beyond conventional diagnostic tools when visiting a patient whose CT scan looks normal yet experiences fatigue and breathlessness. Not knowing what causes the abnormalities observed in this group of patients makes treatment extremely challenging. "We need more research to understand the treatment implications and long-term impact of these pulmonary vascular abnormalities in patients with long-COVID," Price concluded.

99 notes

·

View notes

Text

Reference saved in our archive (Daily updates)

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Covid infection and vaccination gives you strong immunity!!! :D to a strain that hasn't been in circulation since May 2020..."

This is why actually reading the studies is key to understanding health news. Repeat infections confer great immunity.... to the "Wild Type" Wuhan strain that originally caused the pandemic.

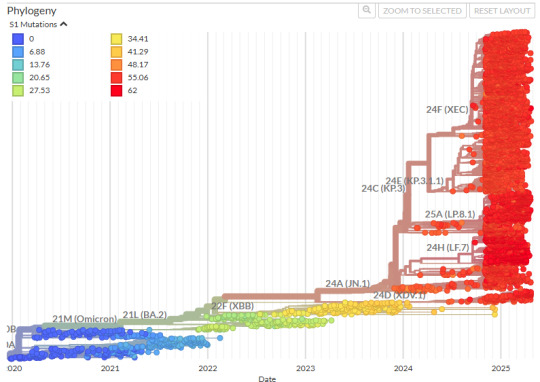

Here's the latest Phylogenic graph of covid strains, if you care:

^This bit right here is what covid infection gives you a good immune response for.

I hope I've made this point abundantly clear and you can see just how ridiculous it is to say things like "covid infection grants immunity." Not any useful immunity.

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

15K notes

·

View notes

Text

Also preserved in our archive (Daily updates!)

Published Sept 3, 2024

By Chuck Dinerstein, MD, MBA

New research reveals that fibrin, a key component of blood clots, may be the secret culprit behind the devastating neurological and inflammatory aftermath of the virus, including long COVID. From dense, stubborn clots to brain fog, the interaction of COVID’s spike protein with fibrin could be the missing link — and a potential target for life-saving therapies.

Coagulopathy, the formation of small blood clots that go on to wreck respiratory and neurologic havoc, has long been a clinical hallmark of COVID, and now it's oft-ignored Long COVID. A new study suggests that fibrin, a key component of blood clots, plays a role.

Fibrin provides structure to a blood clot and is derived from fibrinogen, a soluble blood protein when the coagulation cascade is activated. If you think of a blood clot as nature’s way of plugging a leak, fibrin deposition is frequently found where there is damage to the walls of blood vessels and the vessels making up the blood-brain barrier. Fibrin serves as a plug and a signal for a greater inflammatory and immune response.

Given the unique clinical presentation of clotting in COVID compared to other respiratory viruses, the researchers hypothesized that COVID directly binds to fibrinogen, promoting blood clot formation and altering clot structure and function. They found that the spike protein of the virus binds to fibrinogen and fibrin at specific binding sites, suggesting that the virus might contribute to abnormal clotting by interacting with fibrinogen.

They found that the spike protein altered the structure of clots, making them denser and more resistant to the body’s natural means of removing clots, a process called fibrinolysis. Additionally, the spike protein enhanced the inflammatory signals from fibrin, increasing oxidative forces (reactive oxygen species or ROS) released from macrophages, a first responder of the immune system.

In converting fibrinogen to fibrin, the spike's binding site (epitope) is exposed. Therapeutically, having identified binding regions, the research found that antibodies could disrupt and reduce these pro-inflammatory effects implicated in acute and long COVID. Among the inflammatory effects reduced by blocking the actions of fibrinogen was the deposition of collagen in the lungs, which creates a barrier to oxygen passage and helps to explain the refractory response to supplemental oxygen we have seen in patients.

Fibrin also suppresses natural killer (NK) cells, which are called "natural killers" because they can recognize and kill stressed cells without prior exposure to a particular pathogen, making them critical first responders. The suppression of NK cell activity results in enhancing viral persistence and lung inflammation.

In additional studies in mice, the researchers found that this fibrin-dependent inflammatory response occurs independently of the active virus, suggesting a potential mechanism for persistent symptoms in Long COVID. [1] Therapeutically, in their mouse model, the use of a monoclonal antibody targeting the fibrin epitope, in addition to reducing the lung’s inflammatory response, reduced neuroinflammation (associated with long COVID’s brain fog). There were reductions in fibrin deposition and microglial reactivity “leading to improved neuronal survival and reduced white-matter injury.” Microglia are the primary immune cells of the central nervous system.

To summarize:

Coagulopathy in COVID-19 is a primary driver of thrombo-inflammation and neuropathology rather than a consequence of systemic inflammation. Fibrin plays a causal immunomodulatory role in promoting hyperinflammation, neuropathological alterations, and increased viral load in COVID-19 by modulating NK cells, macrophages, and microglia. Elevated fibrinogen levels and BBB permeability in COVID-19 contribute to neuropathology, and targeting fibrin may offer a dual mechanism of action by inhibiting fibrin-spike interactions and exerting anti-inflammatory effects. A fibrin-targeting antibody effectively blocks many pathological effects of fibrin, providing neuroprotection and reducing thrombo-inflammation. Their findings have limitations, including how they measured changes in brain tissue, the use of mouse models, and the fact that our inflammatory response may have more than one pathway that results in COVID-19’s deleterious effects. For Long COVID, the fibrin-targeted antibody does not interfere with normal clotting, acting solely on fibrin's inflammatory responses, making it a candidate to protect against pulmonary and cognitive impairment; that will, of course, require clinical trials.

And there you have it—the silent saboteur behind the lingering specter of Long COVID. Fibrin is not just a bystander in the aftermath of COVID-19; it's a key player driving the chronic symptoms that continue to baffle patients and clinicians alike. The discovery that the virus’s spike protein meddles with fibrin, transforming it into a resilient, inflammatory force, opens a new frontier in the fight against the pandemic’s long tail. The research, though groundbreaking, is still in its early days, confined to animal models, and the complexities of human biology could introduce new challenges.

But if the science holds, targeting fibrin could offer a two-for-one punch against the clotting and inflammation that underpin much of the damage COVID-19 leaves in its wake. For the millions grappling with the enduring effects of Long COVID, this could be a glimmer of hope—a chance to reclaim their lives.

[1] The inquisitive with a conspiratorial bent might link these inflammatory responses in the absence of infection to deaths felt to be due to the COVID vaccines, which employ the spike as antigenic stimulus. The researchers note that most hematologic changes are triggered by the vaccine vector (an adenovirus) and that “COVID-19 RNA vaccines lead to small amounts of spike protein accumulating locally and within draining lymph nodes where the immune response is initiated, and the protein is eliminated.”

Source: Fibrin drives thrombo-inflammation and neuropathology in COVID-19 Nature DOI: 10.1038/s41586-024-07873-4 www.nature.com/articles/s41586-024-07873-4

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

I am waiting for the world to finally realize what Covid and other viruses can do to your body. Repeat infections are going to have dire consequences.

75 notes

·

View notes

Text

Also preserved in our archive

From January, 2025. A great opinion piece on the socio-political aspects of masking.

276 notes

·

View notes