Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

What challenges exist for the development of transnational feminist thinking and practice? How can these be overcome?

Introduction

The Third Wave of transnational feminism surged in the mid 1980s and has only grown and developed since (Tripp, 2006). Transnational feminist thinking has taken a prominent role in policy shaping and has been the foundation of many activist feminist movements. It can be viewed as a significant global paradigm, which conceptualizes the consequences of neoliberal capitalism and globalization as a shared threat to women’s rights and livelihoods transnationally. International organizations and groups have been active in promoting transnational feminism. The United Nations (UN), for example, has encouraged transnational feminist links through its organizing of international women’s conferences like those in Beijing in 1995 (Tripp, 2006). The growing international involvement has resulted in the exponential growth of transnational feminist linkages in the context of a common antagonist. The latest women’s marches around the globe have shown that these linkages are stronger than before. However, although transnational feminist thinking and practice have developed from the criticisms of previous international feminist theories, there are still many challenges that it faces to develop and further its potential.

This paper will outline the challenges of the development of transnational feminism in both thinking and practice, and outline ways in which these can be overcome or pacified. The challenges relating to its thinking, will be outlined by analyzing the role of knowledge production and examining the function of the nation state, nationalism and geographical location. These challenges however can be overcome by further harnessing the scholarly production from a wider array of theorists from different backgrounds and creating a more analytical framework that borrows heavily from Third World Feminism. The second part of this paper will explore the practical challenges of transnational feminism by looking at the challenges to Transnational Feminist Networks (TFNs), as they are arguably the executing bodies of the thinking. Some of the challenges to TFNs, are the unequal power relations within management structures as well as the challenge of internal and external cooptation. These challenges are problematic and should be overcome by re-examining the management structures, creating various coalitions, as well as reconsidering their funding structures. In general, transnational feminism is a paradigm that can contribute immensely to the furthering and developing of women’s rights and livelihoods, however its challenges should be adequately dealt with for it to reach that potential.

Transnational Feminism Thinking and Thinkers

To explore the challenges for the development of transnational feminist thinking and practice, we must understand the basic components of it first. Transnational feminism is not a clear-cut theory or category in which everyone involved agrees with another other. However, it does offer a conceptual framework and can be practiced as an activist movement. Transnational feminism was termed by Grewal and Kaplan (1994) and was offered as a rejection to the terminology of global feminism. It countered the idea of a “global sisterhood” which arguably ignored an array of apparent differences between women globally (Dubois, 2005). Transnational feminism in thinking, relates the problems for women to the negative effects of neoliberal capitalism and the side-effects of globalization which affect women all over the world, transcending borders. Although women share similar grievances, their differences must be addressed and facilitated. Mohanty (2003a: 530) articulates that an emphasis must be placed on Third World women which in practice means “building feminist solidarities across the divisions of place, identity, class, work and belief”. These solidarities are arguably executed by TFNs which constitute the practicing body of the thinking. Because transnational feminism is not a theory, it is difficult to group these challenges under the same categories. This paper aims to highlight the complexities of transnational feminism both in thinking and practice, outlining that there are not only various thoughts but also different interpretations.

Challenge to Thinking: Knowledge Production Divide

This section will explore a large challenge to feminist thinking; the knowledge production divide. Knowledge production in this context relates to who is creating and constructing the scholarship, research and creating the materials available to and from transnational feminists (IGI Global, 1988). The UN, in its various Women’s conferences such as the Nairobi Conference, has increasingly included more literature and insights produced by Third World women involved in transnational networks into reports (United Nations, 1985). However, while there is “large body of work on women in developing countries, this does not necessarily engage feminist questions” (Mohanty, 2003b: 46). Transnational feminist thinking is arguably also far removed from its practice. According to DuBois (2005) transnational feminism “is being taught at an abstract and theoretical level.” Others believe that the gap in knowledge production has led feminists in the Global North to take on the role of scholars and Third World women the role of activists (Mendoza, 2002). There is a clear division between the intellectual and the practical “labor” divisions. Mendoza (2002) portrays how intellectual work is constructed as something belonging to western and estranged non-western feminist scholars working in the West. She contrasts this to the manual labor that is attributed to the Third World activists. The knowledge production divide, is not so much an active one, as one that has grown organically, however, it should actively be addressed. The challenge is to overcome the knowledge divide, if transnational feminism wants to remain at the forefront of the international feminisms.

Although there have been initiatives to increasingly use knowledge produced by transnational feminists, the delicate challenges proposed above are still existent. One of the ways of overcoming this challenge and further facilitating the growth in literature is to bring knowledge production closer to Third World women. There is a lot of transnational feminist literature out there but is not always given equal prominence and weight. According to Oyewumi (1997), African scholars, in particular women, should bring their knowledge on sharing an African perspective on prospects and challenges. Knowledge produced by Third World scholars should not merely be an exception for the norm or a plain case study in a paper (Oyewumi, 1997). Falcón (2007:180), states that “knowledge production is collective” and that we should work towards a collective attitude towards research organization between not just intellectuals but also activists. However, most importantly, knowledge and literature produced by those from the Third World is not enough. There is a difference between scholarly knowledge production and local knowledge production to which anyone can contribute. Transnational feminists should embody the works of “Other” knowledge producers that are not western educated and are not located in the metropole.

Challenge to Thinking: Role of Nation States, Nationalism and Geographic Location

The knowledge production divide is not the only challenge that transnational feminism faces to its thinking. Moghaddam argues that, “transnational is the conscious crossing of national boundaries and superseding of nationalist orientations (in Mueller, 2006: 78). She clearly separates transnationalism from the nation states, which is a quintessential positioning that can pose a challenge. According to Stasiulis (1999: 182), “feminists everywhere face a complicated process in positioning themselves vis-a-vis nationalism and nationalist politics.” The exclusive focus on the transnational away from the place of the national can pose a challenge. Herr (2015: 42), calls this skepticism of the nation state and nationalism the “incompatibility thesis.” He continues to argue that translational feminists such as Grewal and Kaplan (1994), Alarcon, Kaplan and Moallem (1999) and Moghadam (2005), are all generally suspicious of nationalism (Herr, 2015: 41). Most of these feminists would argue that nationalism is patriarchal and therefore harmful, and some might also argue that nationalism can undermine transnational feminist solidarity. However, transnational feminism might encourage nationalist solidarities and gain support form nationalist movements. Another challenge is the challenge of finding a balance between a focus on the transnational without losing sight of local needs and demands. This is represented by Desai (2007: 337), stating that transnational feminism on occasions masks the role of regional influences which are occasionally more important or just as important as local ones. In the process of globalization, the transnational or global appears to gain precedence over the local (DuBois, 2005). By looking at nationalistic movement and the role of nation states, there can be a further understanding of the local which can strengthen the transnational. Herr (2014: 19) continues to warn that “if transnational feminists were to ignore the internal context of nation-states as unworthy of feminist attention” women’s issues in the Third World at the local level may be neglected. This can pose as an unintended consequence and challenge to not just to its thinking but practice. Desai (2007) argues that, one of the largest challenges to transnational feminism is its unclear positioning on the connections between the local and global. The challenge for transnational feminism is to define their scope and how they will address questions of nationalism, nation states and geographical location in its theoretical conception.

To overcome this challenge, the theoretical foundations of transnational feminism must be re-explored or openly addressed in relation to Third World women’s location. It should include a critical conceptualization the nation state, nationalism and an increased focus on the local. Herr (2014) argues that transnational feminism needs to reclaim the Third World feminism to “promote inclusive and democratic feminism”. Third World Feminism according to Herr (2014) is different to transnational feminism because it places an increased focus on the local and national. Third World feminism places its core emphasis on Third World women, and doesn’t aim to homogenize and view oppressions to “all” women as equal. There should be an increased focus on cooperating with the state, to bring across feminist agendas. However, the involvement with the nation state and nationalism should occur on a case by case analysis. By operating with the national, the cooperation in the transnational context will be facilitated. Stasiulis (1999: 183) argues that there is “a need to develop a conceptual apparatus” that can focus on the plurality and locations of various nationalisms. Herr (2015) goes even further and contends that transnational feminists should challenge the conception of the incompatibility thesis by focusing on “polycentric nationalism” which regards nationalism as de-essentialized. Not only should it be de-essentialized but according to Tripp (2005) regional discussions and diffusions can play a large and important part in transnational feminism. The conceptualization of transnational should be expanded upon to include the importance of other elements within transnationalism. It must develop a contextual framework that better addresses the role of the local and the nation state to consolidate its reach and efficiency.

Challenges to Practice: Challenges for Transnational Feminist Networks (TFNs)

TFNs are “structures organized above the national level that unite women from three or more countries around a common agenda, such as women’s human rights, reproductive health and rights, violence against women, peace and antimilitarism, or feminist economics” (Dempsey, 2006: 481). TFNs have been hailed for having been able to transcend local and national differences and are arguably at the center of “women’s political awakening” and are increasingly involved with intersectional women (Moghadam, 2000: 77). They embody the practice of transnational feminism and networks such as DAWN, WIDE and AWM have been highly successful (Moghadam, 2005). However, TFNs face two challenges, one being the power relations within networks and the other being the challenge of co-optations.

Power Relations

One of the continuous challenges is that TFNs, even the most “successful” and established are still comprised of “largely middle-class, highly educated women” (Moghadam, 2000). This is a challenge for the management of networks and the consequent effectiveness. Conway (2013) also addresses this concern stating that, “the members of transnational networks are educated, cosmopolitan women” and we must therefore focus on regional visions on grassroots women. Transnational feminism can be divided by power relations. The critique from Third World women is often that of the “unequal power relations” within not just their own network but the global network (Kurian et al., 2015: 873). These challenges can also come in the form of more technical differences that create unintentional challenges. Kurian et al. (2015: 873) mention this more technical problem, stating that there is a gap between people who have access to the internet and those who do not have access to transnational networks. This practical example shows how power relations might not be intentional but they remain problematic. As Peggy Antrobus (2015: 873) highlights, the “challenge is to find the right balance between a management structure that is efficient and accountable” but also represent networks and transnationalism. Even though TFNs are blooming up on all levels, international and grassroots, a conscious effort should be made to analyze who the ones are that are in power making the decisions and what their intentions are.

Cooptation

There are also additional practical problems, of which the biggest challenge is cooptation (Brenner, 2003). Cooptation can be defined as the appropriation and exploitative assimilation of a social movement. There are two types of cooptation that pose a challenge. The first type of cooptation relates to the subsuming of smaller groups and organizations into larger more established TFNs. The second form of cooptation relates to the cooptation of TFNs by states and larger international organizations. Both pose a challenge to the development of transnational feminism. The cooptation of many smaller organizations by large powerful TFNs can be a challenge to the nature of transnational feminism but also its effectiveness. As Alvarez and Gal, question; what happens to nascent local movement when transnational forms of feminism are transplanted across the globe? (in Hrycak, 2007: 75). This question is one that is not just a challenge to practice but also its theoretical conceptions. TFNs have the challenge of finding a balance between collaboration and co-optation. Although it is essential to include smaller feminist networks with local roots into large TFNs, the challenge is how to find an equal power balance, not letting local grassroots groups disappear in the process of expansion.

The second context of cooptation relates to the cooptation of TFNs by states or international organizations for furthering broader political agendas. One of the most widely used examples of how TFNs and the transnational feminist discourse were coopted is the example of the War on Terror rhetoric used. George Bush claimed that the War on Terror was a war to protect the rights of women (Brenner, 2003: 29). This claim, along with funding needs, led many TFNs to give their support for the US intervention in countries such as Afghanistan (Brenner, 2003). The examples where states have coopted TFNs, could provide a reason for the cautious attitude of transnational feminism towards including the roles of nation states. The co-optations of these TFNs and movements by state agencies is possible because of their dependence on state funding (Hall, 2015). The two potential co-optations of smaller feminist organizations or large TFNs by state apparatus or political agendas pose big challenges for the effectiveness and growth of TFNs.

For TFNs to overcome these institutional and foundational challenges they should rethink various practical components. Garita (2015) has pointed out the need to further build coalitions between TFNs as well as local organisations and networks, on an even-footed basis. Coalition building is essential in overcoming the power relations challenges that many TFNs face (DuBois, 2005). The power balances need to be addressed and re-addressed continuously to facilitate equal power relations within TFNs. TFNs should actively focus on including Third World women in their management teams (Herr, 2014). To prevent the continuation of disparities among women within TFNs, local movements and networks should not be “sucked up” into the TFNs but be gradually adopted into the local, maintaining their missions. The challenge of the cooptation by states and larger political agendas poses a larger challenge. If, as Hall (2015) argues, there is a connection between state funding and levels of cooptation then, funding structures should be changed. There should be greater inclusion and cooperation within TFNs so that they can become powerful lobby groups, and derive their own funding structures. By increasing the strength and efficiency of TFN coalitions it will be much harder for them to be co-opted. 7

Conclusion

Transnational feminism is not a theory but rather a collective way of thinking about international feminism. Transnationalism operates from the premise that borders are transgressed and that this is beneficial without losing sight of intersectional differences. Most likely transnational feminism will increase in size and reach as global contexts increasingly permit this through the facilitation of TFNs. However, arguably transnational feminism is not perfect both in its thinking and conceptualization as well as its practice. It encompasses a lot of potential, but it can only develop and grow if the challenges are addressed. With regards to the challenges to its thinking, the challenges of knowledge production and the positioning of nations, nationalism and locations, pose the biggest challenge. They are conceptual and systemic ambiguities that need to be addressed in further thinking. This can be done by further knowledge-sharing initiatives, consciously using and employing scholarship from Third World women not just from the South but in the South and using this literature not as a mere footnote on an international report but the body of these reports. Although transnational feminism is not a theory it should re-conceptualize and reemphasize the notion and the role of states and location, so as not to become removed from that which they are wanting to encourage. With regards to the challenges in practice, they can be articulated through analyzing TFNs. TFNs have become phenomenal forces of change facilitating feminist agendas, they still face some challenges such as power relations in management and cooptation both by TFNs and powerful state actors. To address the power relations, conscious efforts need to be made to tackle these and thereby change them, and funding systems must change to maintain autonomy. With regards to the challenge of cooptation, funding is also an essential component but so is coalition building between TFNs and women’s movements. All in all, transnational feminism is the type of feminism that has the potential to accurately reflect current needs in our globalized world, however to fulfill this potential it should first address its challenges and overcome them. 8

Bibliography

Antrobus, P. (2015). DAWN, The Third Word Feminist Network. In: R. Baksh and W. Harcourt, ed., The Oxford Handbook of Transnational Feminist Movements, 1st ed. Oxford: Oxford University, pp.159-187.

Brenner, J. (2003). ‘Transnational Feminism and the Struggle for Global Justice’, New Politics, 9(2), pp. 25–34.

Conway, J (2013). Edges of Global Justice: The World Social Forum and Its Others. London: Routledge.

Dempsey, S.E. (2006). ‘Review: Globalizing women: Transnational feminist networks by Valentine M. Moghadam’, Women’s Studies Quarterly, 34, pp. 481–486.

Desai, M. (2007). ‘Review: The Perils and Possibilities of Transnational Feminism’, The Feminist Press at the City University of New York, 35(¾), pp. 333–337.

DuBois, E. (2005). ‘Transnational Feminism: A Range of Disciplinary Perspectives’, Royce Hall: UCLA.

Falcón, S.M. (2016). ‘Project MUSE - transnational feminism as a paradigm for Decolonizing the practice of research: Identifying feminist principles and methodology criteria for US-based scholars’, Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies, 37(1), pp. 174–194.

Garita, A. (2015). Moving Toward Sexual and Reproductive Justice: A Transnational and Multigenerational Feminist Remix. In: R. Baksh and W. Harcourt, ed., The Oxford Handbook of Transnational Feminist Movements, 1st ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp.271-294.

Grewal, I. and Kaplan, C. (1994). ‘Introduction: Transnational Feminist Practices and Questions of Postmodernity’, in Grewal, I. and Kaplan, C. (eds.) Scattered hegemonies: Postmodernity and transnational feminist practices. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Hall, R. (2015). Feminist Strategies to End Violence Against Women. In: R. Baksh and W. Harcourt, ed., The Oxford Handbook of Transnational Feminist Movements, 1st ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 394-418. 9

Herr, R.S. (2014). ‘Reclaiming Third world feminism: Or why transnational feminism needs Third world feminism’, Meridians, 12(1), pp. 1–30.

Herr, R.S. (2015). ‘Can transnational feminist solidarity accommodate nationalism? Reflections from the case study of Korean “Comfort Women”’, Hypatia, 31(1), pp. 41–57.

Hrycak, A. (2007). ‘From Global to Local Feminisms: Transnationalism, Foreign Aid and the Women’s Movement in Ukraine’, Sustainable Feminisms, 11, pp. 75–93.

IGI Global (1988). What is knowledge production. Available at: http://www.igi- global.com/dictionary/knowledge-production/41635 (Accessed: 5 March 2017).

Kurian, P., Munshi, D. and Mundkur, A. (2015). The Dialectics of Power and Powerlessness in Transnational Feminist Networks. In: R. Baksh and W. Harcourt, ed., The Oxford Handbook of Transnational Feminist Movements, 1st ed. Oxford: Oxford University, pp.871-894.

Mendoza, B. (2002). ‘Transnational feminisms in question’, Feminist Theory, 3(3), pp. 295–314.

Moghadam, V.M. (2000). ‘Transnational feminist networks: Collective action in an era of globalization’, International Sociology, 15(1), pp. 57–85.

Moghadam, V.M. (2005). ‘The Women’s Movement and Its Organizations: Discourses, Structures and Resources’, in Moghadam, V.M. (ed.) Globalizing Women: Transnational Feminist Networks. Baltimore: The John Hopkins University Press, pp. 78–104.

Mohanty, C.T. (2003a). ‘“Under western Eyes” revisited: Feminist solidarity through Anti-capitalist struggles’, Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 28(2), pp. 499–535.

Mohanty, C.T. (2003b). ‘Cartographies of Struggle: Third World Women and the Politics of Feminism’, in Mohanty, C.T. (ed.) Feminism Without Borders: Decolonizing Theory, Practicing Solidarity. Durham: Duke University Press, pp. 43–84. 10

Oyewumi, O. (1997). ‘Visualising the Body: Western Theories and African Subjects’, in Oyewumi, O. (ed.) The Invention of Women: Making an African Sense of Western Gender Discourses. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, pp. 1–30.

Stasiulis, D.K. (1999). ‘Relational Positionalities of Nationalisms, Racisms and Feminisms’, in Kaplan, C., Alarcon, N., and Moallem, M. (eds.) Between Woman and Nation: Nationalisms, Transnational Feminisms, and the State. Durham: Duke University Press, pp. 182–218.

Tripp, A.M. (2005). Regional networking as transnational feminism: African experiences. Feminist Africa, [online] (4), pp.46-63. Available at: http://agi.ac.za/sites/agi.ac.za/files/fa_4_feature_article_3.pdf (Accessed 20 Mar. 2017).

Tripp, A.M. (2006). ‘The Evolution of Transnational Feminisms: Consensus, Conflict and New Dynamics’, in Ferree, M.M. and Tripp, A.M. (eds.) Global Feminism: Transnational Women’s Activism, Organising and Human Rights. New York: New York University Press, pp. 51–78.

United Nations (1985). Report of the World Conference to Review and Appraise the Achievements of the United Nations Decade for Women: Equality, Development and Peace. Available at: http://www.un.org/womenwatch/daw/beijing/otherconferences/Nairobi/Nairobi%20Full%2 0Optimized.pdf (Accessed: 5 March 2017).

0 notes

Text

Providing Help or Contributing to Hardships? The Role of Social Media and Technology in Shaping the Refugee Experience.

Introduction

The images of refugees crowding around power outlets with their IPhone chargers or taking selfies with their selfie-sticks, are images that have been shared by many news outlets supposedly signifying the nature of the refugee experience in the 21st century. These images however only represent a small pixel of the larger picture. Europe has seen unprecedented numbers of refugees, from primarily Syria but also nations such as Iraq and Afghanistan, come to seek refuge in the last years (BBC, 2016). The “European Migration Crisis” reached its peak in 2015, with the arrival of approximately 1,800,00 migrants (BBC, 2016). The current “crisis” is new by nature because it is taking place during the digital age, where communication and surveillance technologies are rapidly increasing in ability and reach. Therefore, there is an increased need to further analyze what roles these technologies play in shaping and making the refugee experience.

Before outlining the structure of this paper, it is essential to understand the terminologies brought forward in the research question. The term “refugee”, is a legal term for an involuntary migrant who has been forced to flee their country due to a well-founded fear of persecution (Shacknove, 1985). Legally this term is given to those that have acquired “refugee status.” Prior to them legally being defined as refugees they are categorized as asylum seekers, however for the coherency purposes, this paper shall refer to them as refugees. Social media will be comprised of online social networking platforms and technology will refer to both communication technologies and include surveillance technologies. Providing help will imply facilitating the agency and movement of refugees, whereas contributing to hardships will refer to obstacles that obstruct the refugee experience. These terminologies aim to illuminate the complexities and nuances that may arise.

This paper will commence by providing a contextual foundation to its work, exploring what has been written about this topic by drawing upon literature from various areas and fields of study. This paper will argue that social media and technology are neither providers of help nor always contributors to hardships. To articulate this, the initial section will look at how social media and technology are used and the extent to which they have facilitated social needs and provided valuable information assisting the journey to Europe. The second section of the paper will investigate how social media and technology can be instruments of hardship, posing as manipulative tools for smugglers and tools of control for states and arguably international actors, reducing refugee’s agency in determining their experience. The final section will aim to clearly elucidate the versatility of both roles by looking at how the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) has used social media and technologies and for what purposes. Overall, social media and technology do not have mutually exclusive purposes. This paper aims to show how these devices and platforms are tools that have dynamic roles in the refugee experience, which can change depending on who employs them and what their changing agendas might be.

Literature Review

This section will set the contextual framework of the paper and provide an overview of existing literature, coming from a wide range of disciplines, looking at migration theories, media studies and theories of government and control.

Refugee Experience

The ‘refugee experience’ as a field of study as well as a theory is useful in setting the conceptual framework of this paper. The concept of the refugee experience was introduced by professor Barry Stein in the 1980s. Stein (1980) argued that the experiences of refugees were collective rather than temporary or unique. The term refugee experience was further expanded upon by psychologist Alastair Ager (1999). He outlined these phases as stages, consisting of the stages of pre-flight, the flight, temporary settlement and re-settlement (Ager, 1999: 3). He categorized the pre-flight stage by the economic hardship, social disturbance, physical violence and political oppression faced. He defined the flight stage by the processes of separation, passage, reception and temporary settlement, this is a stage of high “emotional and cognitive turmoil” (Ager, 1999: 7). The third stage, temporary settlement, is related to the registration in refugee camps and the last stage concerns the phases of integration in their final host country (The Refugee Experience, 2017). According to BenEzer and Zetter, (2015), scholars have not yet accurately explored how digital technologies may influence the stage of flight because focus has been primarily on the fourth stage. Therefore, this paper will put an emphasis on the first three stages of the experience to explore an underexplored area of the refugee experience in relation to social media and technology.

Social Needs

There is currently ample research on the roles that social networks and social relations play in aiding refugee welfare (Palloni et al., 2001; Bourdieu, 2011; Cheung and Phillimore, 2013; Haug, 2008; Massey, 1994). In the late 1980s, sociologist Pierre Bourdieu came up with the notion of social capital. He defined the term as encompassing the potential of resources that are derived from the possession of a resilient network of established relationships between acquaintances (in Palloni et al., 2001: 86). Within theories of migration, social networks offer important foundations for social capital, which not only lead but contribute to a strong social support system (Ryan, 2008: 763). The theory of Uses and Gratifications, borrowed from media studies, is useful for studying the reasons for social media usage. The theory developed by Katz, Blumler and Gurevitch (1973) outlines the importance of media usage in maintaining the social and psychological needs of individuals. Both theories provide a theoretical basis for the premise that technology and social media shape the refugee experience, by shaping the networks in it.

Guidance and Information

Social media and technology adopt both a helpful role when they enable social capital and networking abilities and when they act as platforms providing technical information for the journey. Information provided by those who have previously made the journey can prove as both a resource and a stimulant for other refugees to make the journey. This is explored by E.F Kunz (1973) in his Kinetic theory, where he distinguishes between anticipatory refugee movements and acute refugee movements. He defined anticipatory refugees as those who leave as a preventative measure, before their situation further deteriorates. Whereas acute refugees, leave during the conflict and can use information provided by those who have made the journey before them. A further useful concept is that of the “strength of weak ties” which is introduced by Granovetter (1983). He argues that relative connections based on ethnicity, religion, culture and acquaintances can become sites of bonding and greater information sharing. Azi Lev-On’s (2011) adds on to this theory from a media studies angle, further articulating how these bonds can facilitate virtual communities. However, the acknowledgement of who employs the technology and how that affects the information is not explored in as much depth but will be in this paper.

Smuggling

Recent research conducted by Birnbaum (2015), Spittel (1998), Nadig (2002) and Papadopoulou (2004), has shown how human smuggling and the refugee experience are highly interconnected without directly looking at the role of social media. The smuggling of migrants is defined by the United Nations as transporting people, to receive directly or indirectly, monetary or other physical advantage of the illegal entry of a person into a state (Kyle and Koslowski, 2011: 7). Birnbaum (2015), a journalist, working at the Washington Post, has done an elaborated journalistic investigation into smuggling. The literature on smuggling and its relationship to technologies and social media are still very new and this paper aims to link them together. It aims to show how social media has played a role in facilitating smugglers’ misleading marketing techniques, providing false information and contributing hardships.

Surveillance and Biometrics

The increased use of surveillance and biometric technologies to control refugee populations can pose a serious hardship during all three initial stages of the refugee experience. The narrative of security is often employed by nation states to justify measures that surveil and constrain the mobility and agency of refugees for control purposes (Briskman, 2013; Bigo, 2002; Holmes and Castaneda, 2016; Gillespie et al., 2016). Philosopher Michael Foucault’s theory of governmentality, defined as the activity employed by governments “which rationalizes its exercise of power”, is highly applicable to the context of securitization and migration (in Fimyar, 2008: 5). According to academic Didier Bigo (2002: 65), technology, in the context of the securitization of migration, is used as a tool of governmentality. Bigo highlights how postmodern societies currently use a form of governmentality called the “ban-opticon” borrowing from Foucault’s idea of pan-opticon. With this he outlines how technologies of surveillance split and classify the masses based on narrow profiles (Bigo, 2002: 82). Bigo’s work is essential in drawing Foucault’s theory of governmentality into the migration context. Foucault et al.’s (2009: 16) further work on biopolitics and biopower highlights how biometrics are employed for the purposes of political power. Biometrics, are defined as devices that can automatically detect a person based on his/her physical features through technologies (Petermann, 2007: 155). Whereas biopower is state power over the biological and physical bodies in a population (Pugliese, 2010). Aas (2006: 143) argues that the “surveillance of the body” is becoming a large part of identifying refugees and an important source of social exclusion hindering the refugee experience. Much of the research on biometrics and migration looks at how they contribute to the efficiency of protection of refugees (Farraj, 2011: 891) however, there is less of a focus on how technologies are increasingly employed for the purposes of governmentality, contributing to refugee hardships.

The literature review has provided the theoretical foundation of this paper. The refugee experience as described by Ager (1999) will provide the stages of the experience throughout this paper. The first two sections will look at what Bourdieu termed social capital as well as Grewal, Blumer and Gurevitch’s theory of Uses and Gratifications (1973), Kunz’s kinetic theory (1975), Granovetter’s (1983) theory of weak ties and Lev-On’s (2011) conceptualization of virtual communities. With regards to the role of contributing to hardships, the limited works on smuggling and technology will lead to a focus on Birnbaum’s (2015) journalistic work and in relation to the hardships created by surveillance and biometrics, there will be an increased focus on Bigo’s (2002) and Foucault et al.’s (2009) work. The next section will explore the various roles of technology and social media and how and in what ways they shape the refugee experience.

Providing Help

Social Needs

Social media platforms such as Facebook and WhatsApp have become a “vital lifeline” for refugees (Gillespie et al., 2016: 45). This section will explore how this is the case for refugees especially at the second and third stages of the refugee experience. During the flight stage and temporary settlement stage, refugees use these platforms and their mobile technologies to keep their friends and families up to date on their journeys which can offer them encouragement and provide psychological wellbeing (Gillespie et al., 2016). It also provides them with social capital as defined by Bourdieu, which is essential not only for maintaining networks but for creating them.

The existence of these devices and platforms have often encouraged people to embark on the perilous journey, knowing that their social networks will stay alive (Gillespie et al., 2016). An article written about the possessions of the refugees who had arrived in Lesbos, tries to highlight what physical possessions were most prized, highlighting the argument (Rizvi, 2015). The people interviewed ranged both in age and nationality but most of them had included their phone as one of their most important possessions, because it allowed them to stay connected. WhatsApp is an app that allows the sending of texts and calling people for ‘free’. It is even referred to as an interactive “window into an old life” (Manjoo, 2016). These platforms have facilitated the social networks of many refugees by allowing them to stay connected. Dekker and Engbersen (2013: 401), state that one of the ties that it promotes is with family and friends. The strengthening of these ties is a vital part of their daily experiences during the flight stage (Gillespie et al., 2016). It influences not only the decision to leave, knowing that they will be able to stay in touch with their loved ones, but also how they experience their journey.

Social media and technologies that enable social communication can provide refugees with psychological necessities. The Uses and Gratification theory has contributed to the idea that the purpose of technology is to carry out a “need”. According to them social integrative needs are amongst the most important for the psychological and social wellbeing of individuals (Katz, Blumler and Gurevitch, 1973). This can be adopted by the refugee context easily. The absence of a stable family network or friendship network is identified as a key aspect negatively influencing the mental health of refugees (Scottish Refugee Council, 2016). By providing social needs, mental health needs are also influenced. Clinical psychologist, Emily Holmes, conducted research on refugees in Stockholm and identified that technology offers potential for creating mental and social wellbeing for refugees at all stages of the refugee experience (Abbott, 2016). Social media and technology can offer the continuation of these networks albeit not physically. Although there are many fragilities and impracticalities that these apps and devices experience, social capital and social networks have dramatically increased the social as well as psychological wellbeing of refugees when they have been in the hands of refugees.

Information and Guidance

Closely related to the social capital and network potential of these technologies and platforms is their ability to provide information and guidance. As mentioned in the literature review, acute refugees, those leaving during violence, have more information at their disposal which is facilitated by social networks and weak ties (Kunz, 1973). Furthermore, through mobile phones they can share images, advice, maps and words of caution (Frouws et al. 2016). King (2013) suggests that social media allows for weak ties to become increasingly expansive leading to augmented social capital. Weak ties allow for the social network to expand and more information about the journeys to be disseminated (Granovetter, 1983). These ties are increasingly facilitated by social media, shaping how information is used and where it is acquired during the refugee experience.

The sharing of information through social media platforms can result in what Lev-On (2011: 100) calls virtual communities. These communities are an invaluable tool and are necessary in shaping and facilitating the refugee experience. Research conducted by the IOM on Iraqi refugees residing in Europe showed that 23% used social media and 22% the internet to design their journeys (Frouws et al., 2016: 2). Lev-On (2011: 109), argues that social media platforms have the potential to become not just virtual communities but organizational “hubs” in which the different actors in the humanitarian field can act together to coordinate their efforts. Information that the mobile devices provide are invaluable, and these do not only have to be social media platforms connected to the internet or WIFI but they can also be ‘offline’ maps or translation services.

Gillespie et al. (2016: 46), articulates the importance of these devices by stating that the “digital infrastructure” is just as important as physical infrastructure in controlling and facilitating the movement of refugees. For example, in European countries like Germany and France, a website called Refugeeinfo.eu has been useful in providing information to refugees. This page loads on the internet pages when refugees connect to WIFI hotspots which is vital during the second stage and third stage of the refugee experience (Cogan, 2016). The website knows the location of the person and provides information about housing, services and other valuable insights (Cogan, 2016). Currently more than 105,000 people have accessed the website and 33,000 use the website daily (Cogan, 2016). However, as (Gillespie et al. 2016) cautions, we should not let techno-optimism view mobile devices as a cure-all to end the refugee crisis, there are many complications. One of the most precarious being the problem that the beholder and provider of this information has immense knowledge power choosing not only what is shared but with whom. It cannot be exclusively argued that these devices have disseminated valuable information facilitating the journey, the actors sharing this information and their intentions must also be assessed.

Contributing to Hardships

Online Smuggler Platforms that Mislead

Despite the beneficial qualities of technology and social media, social media has helped provide a platform for smugglers, to “sell lies” and provide false promises, exploiting the vulnerable position of refugees. The smuggling in the context of this paper will look primarily at smugglers offering transportation services across seas and illegal documents. Smuggling plays a large role in the pre-flight stage but also the flight stage, contributing to increased dangers for refugees (Birnbaum, 2015). Aljazeera reports that in 2016 alone, 2,500 refugees drowned making their way to Europe (Al Jazeera, 2016). Although some argue that smuggling is a business that is about aiding refugees and that it is only made possible by restrictive European policies, smugglers as a group are not humanitarian workers as evidence shows (Birnbaum, 2015). Smugglers can take advantage of the situation that refugees are in in their pre-flight stage and not only deprive them of their safety but their human dignity by taking advantage of their position as the “only” solution.

Smugglers are involved in illicit but highly prosperous and booming businesses that smuggle refugees to primarily European countries by different means of transportation (Birnbaum, 2015). Smugglers often demand unrealistic fees and do not guarantee the safety of their clients (Birnbaum, 2015). Many smugglers are using online social media platforms to advertise their business by promising lies (Gillespie et al. 2016). Although it can be argued that refugees have consented and made the choice to be smuggled, that does not imply that hardships are obsolete and their vulnerable position cannot be exploited. Smuggler, Musumeci Yachts claims that his “company” made around 215 million pounds in 2015 (Adamson and Akbiek, 2015) an obscene amount seeing the fragility of the journeys they offer. The wars in Libya and in Syria have provided opportunities for smugglers to expand their businesses. Although arguably these businesses have made it easier for refugees during their flight stage to travel to Europe in reality it has also made it more dangerous because of the exponential circulation of false promises and advertisements.

After having conducted research on a smugglers’ Facebook page, it became clear how desperate and willing refugees were and how these needs were exploited by smugglers which is articulated by the Facebook Page, translated to “For asylum seekers legal and illegal immigration to any state (Facebook, 2016). These people are often offered false promises, but due to their precarious decision take the risk (appendix a). Some smuggler Facebook Pages have uploaded pictures of luxury yachts (appendix b) promising a journey across the sea in luxury, which is often fabricated (Adamson and Akbiek, 2015). What is important to analyze is who is employing and commanding this Page and for what purposes. Social media and technologies, such as cellphones that contain apps such as Viber, Whatsapp and Facebook, have provided an easy way to advertise routes to Europe arguably facilitating the flight stage, by allowing them to circumvent restrictive state policies. However, there has been heightened dissemination of false promises on these platforms leading to the exploitation of refugees and the creation of hardships.

Surveillance and Biometric Technologies of Control

Additionally, social media and technologies are used by states of both the departing nations and the host countries for the purposes of control. In the pre-flight stage, potential refugees are increasingly more surveilled through their technologies and platforms serving to prevent them from fleeing. Wall, Otis Campbell, and Janbek (2015), use the example in which Syrian refugees are monitored to portray this. The largest phone operator in Syria, SyriaTel, is operated and owned by, Rami Kakhluf, who is the cousin of President Assad. Phones using this provider are increasingly subject to monitoring which puts those considering fleeing in danger. The Freedom House Report in 2012 (Wall, Otis Campbell, and Janbek, 2015) highlights how the Syrian government filters the messages and has developed a software for monitoring and tracing phone calls, emails and other digital and social media platforms. Many refugees have tried to work around this increased surveillance by changing SIM cards and using coded language (Wall, Otis Campbell, and Janbek, 2015) however, these are not available to all and still pose a danger.

During the pre-flight and flight-stage, recent developments in Europe have justified amplified surveillance and the use of biometrics. Refugees are surveilled in two ways; one way is that their devices and social media platforms are being confiscated or monitored and the second way is that their bodies are surveilled using biometrics for the purposes of control.

The first way in which refugees are surveilled is through their technologies which limits their refugee experience. According to Harney (2013), host countries have increasingly started to adopt surveillance technologies, explicitly aimed at “risk management” (Gillespie et al., 2016: 34). This type of risk management views refugees as potential terrorists and threats and does not seek to offer them protection but offer protection from them, acting as a tool of governmentality. In June 2016, the Federal Secretary of State for Asylum and Migration in Belgium, wanted to adopt a law in parliament that would allow the immigration authorities in Belgium to search the digital devices of all refugees (Bellanova, Gabrielsen Jumbert, and Gellert, 2016). These developments have created hardships for refugees, by taking away or exploiting their usage of these technologies.

The second way in which refugees are surveilled is through surveillance technologies especially biometrics. Biometrics, as was defined in the literature review, has increasingly been employed by EU governments and agencies in establishing ‘smart borders’ (Petermann, 2007). Petermann (2007) expresses his worries of the “political technology” of migration. Biometrics are often employed in the name of securitization (Bigo, 2002), however it often disregards the wellbeing and refugees power in shaping their own experience. In Norway, the government has even made it mandatory to take X-Ray photographs of the hands of teenage refugees to ensure that their ages match up with their story (Aas, 2006: 147). What these examples highlight is that refugees are scrutinized within the system and their bodies hold the key to their identity, reducing their agency (Aas, 2006). Not only is the theoretical foundation of the use of biometrics harmful but so is the notion of data sharing. The privacy of refugees is hardly the focus of protection measures, instead the refugee is assumed to be protected because of assumed physical protection (Jacobsen, 2015: 158). According to Diaz (2014: 10) organizations such as the IOM and the UN have failed to set compulsory standards for data protection. The sharing of biometric data can be dangerous, as this information, when used in the hands of government agencies with the rhetoric of security, can foster a type of governmentality that constrains the refugee experience.

The Role of the UNHCR and Technology: Providing Help or Contributing to Hardships?

This section aims to tie together the points made in the sections above and argue that technology and social media are not mutually exclusive categories. The nature of the role depends not only on who is employing it but how they decide to employ it. The UNHCR is an agency of the United Nations, created in 1950 with the Geneva Convention in response to the aftermath of the second World War. Its initial responsibilities are devising permanent solutions, international protection and material assistance through efficient allocations of resources (Hammerstad, 2015: 70). The case of the UNHCR aims to highlight how it uses social media and technology for both purposes of providinghelp and contributing hardships. It aims to demonstrate that even if the actor is the same, their intentions and uses are not static.

The UNHCR is increasingly using and harnessing the potential of social media and technologies in relation to provisionary roles at all three stages of the experience. In relation to its direct assistance to the social wellbeing of refugees, the UNHCR has taken, social capital and the realities of the use of technologies by refugees, under consideration. According to Brunwasser (2015), the UNHCR has “distributed 33,000 SIM cards to Syrian refugees in Jordan along with 85,704 solar lanterns that can be used to charge cellphones” in the Za’atari Refugee Camp. These actions have allowed for many of these refugees to remain in contact with their family and can have access to important information regarding security and service issues (Rouse, 2015). These developments are arguably taking on the role of providing help and giving agency to refugees. Not only does the UNHCR focus on the immediate needs of refugees but they are becoming more involved in disseminating information on Facebook groups and pages, about the dangers omitted from smuggling advertisements (European Migration Network, 2016). They are focusing on establishing a relationship with the European Asylum Support Office (EASO) to monitor social media and counter narratives of those shared by smugglers (Tomlinson, 2016). The UNHCR also promotes their use of biometric registration technologies in refugee camps, stating that this process will increase the efficiency of the provisioning of services and goods to refugees arriving in camps. However, this is one of the most contested areas of their work which will be explored in the following section.

The UNHCR, as observed by Hammerstad (2015: 145) has become “an integral part of the UN’s global security efforts.” This shift has led some to believe that the UNHCR, has become “the global police of populations” (Scheel and Ratfisch, 2013: 924). Using the language of Foucault, Bigo (2002) argues that governmentality has strengthened the international actors in “managing” refugees and that it has united these actors in the name of securitization. Governmentality and biopolitics are not only employed by state actors but also international agencies. The UNHCR has arguably been one of the leaders in the use of biometric registration in refugee management (Jacobsen, 2015: 145). The primary hardship associated with the information collected from these technologies is that data is not private and is used for political agendas. Jacobsen (2015: 154) asserts that biometrics employed by actors such as the UNHCR, “contribute to the construction of the refugee as a new domain of knowledge and intervention.” Donors of the UNHCR want to have access to much of the registration data for various purposes. The ambiguity of the term “various purposes” is highly dangerous. Jacobsen (2015) maintains that the USA has used refugee data from Iraqi refugees for Homeland Security issues, not to protect Iraqi refugees but rather their own citizens. The UNHCR guidelines state that information is not allowed to be shared with other actors or states unless it is in the name of security (Bohlin, 2008). However, yet again, the vagueness of this term is often abused. Bohlin (2008) believes that the UNHCR is placed in precarious location within the refugee regime, being used as a pawn. She argues that the UNHCR is not able to resist “potential data-sharing requests” from states, as their funding and position in the regime is sometimes dependent on it (Bohlin, 2008: 155). However, the UNHCR, due to its pivotal position in the regime, has a greater responsibility towards refugees which it should maintain. The examples above have shown how the UNHCR, has intentions, agendas and audiences change, therefore they don’t exclusively help or provide hardships but rather do both.

Conclusion

The transnational nature of social media and technologies have both enabled and disabled refugees during the various stages of the refugee experience. Technologies like cellphones and apps like Whatsapp are not merely fancy gadgets that the wealthy strata of society have access to but are basic tools accessible to most. These tools, when employed and used, by refugees and facilitated by organizations like the UNHCR for the purposes of providing access to social networks and information, can make the refugee experience easier. It can enable free movement and access to home simpler increasing their social capital and wellbeing. These tools play a large role during the pre-flight and flight stage when refugees are deciding if they want to flee and how but also if they can remain connected to family and friends. However, it is vital to understand that when these tools are ‘hijacked’ or are used by actors such as smugglers, and various national and international agencies, the tools can become contributors to hardship. They can make the journey not only more dangerous but also exploit refugees for control purposes. Starting from the pre-flight stage, smugglers and government surveillance organisations can have access to social media platforms but also the actual technologies. By taking these tools or using them as platforms, they take away the agency of refugees and often also their mobility. During the flight stage, social media and technologies such as cellphones are literal lifelines but they can also be used by actors such state agencies, to hamper their experience. Technologies and social media in the hands of states and institutionalized organizations can be tools of a restrictive governmentality. Biometric technologies employed by both states and their agencies as well as the UNHCR, reduce the agency of refugees to mere bodies, creating further hardships and dangers for them along the way. As Postman (1992:4) states, “every technology is both a burden and a blessing, not either-or but this-and-that.” The role of social media and technology in shaping the refugee experience is influenced by who employs it and for what purposes. As the UNHCR discussion aimed to show, the roles of these tools can change and are not fixed, even if they are employed by one actor. Social media and technology can never be understood as a panacea and the developments in these technologies will only progress, resulting in both new potential but also different unknown hardships.

Bibliography

Aas, K.F. (2006) ‘“The Body does not Lie”: Identity, Risk and Trust in Technoculture’, Crime Media Culture (CMC), 2(2), pp. 143–158.

Abbott, A. (2016) Refugees Struggle with Mental Health Problems Caused by War and Upheaval. Scientific American. Available at: https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/refugees-struggle-with-mental-health-problems-caused-by-war-and-upheaval/ [Accessed 16 Mar. 2017].

Adamson, D. and Akbiek, M. (2015) The Facebook Smugglers Selling the Dream of Europe. Available at: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-32707346 (Accessed: 28 February 2017).

Ager, A. (1999) Perspectives on the Refugee Experience. In: A. Ager, ed., Refugees: Perspectives on the Experience of Forced Migration, 1st ed. Cassell.

Al Jazeera. (2016) 2, 500 refugees drowned on way to Europe in 2016. Available at: http://www.aljazeera.com/news/2016/05/unhcr-2500-refugees-drowned-europe-2016- 160531104504090.html (Accessed: 28 February 2017).

BBC (2016) Migrant crisis: Migration to Europe explained in seven charts. Available at: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-34131911 (Accessed: 28 February 2017).

Bellanova, R., Gabrielsen Jumbert, M. and Gellert, R. (2016) ‘Give Us Your Phone and We May Grant You Asylum’, Norwegian Centre for Humanitarian Studies (October).

BenEzer, G., and Zetter, R. (2015) ‘Searching for Directions: Conceptual and Methodological Challenges in Researching Refugee Journeys.’ Journal of Refugee Studies, 28(3), 297-318.

Bigo, D. (2002) ‘Security and Immigration: Toward a Critique of the Governmentality of Unease’, Alternatives: Global, Local, Political, 27(1), pp. 63–92.

Birnbaum, M. (2015) Smuggling refugees into Europe is a new growth industry. Available at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/europe/smuggling-refugees-into-europe-is-a-new-

growth-industry/2015/09/03/398c72c4-517f-11e5-b225- 90edbd49f362story.html?utm_term=.46791ac2aedc (Accessed: 27 February 2017).

Bohlin, A. (2008) Protection at the cost of privacy? - A study of the biometric registration of refugees. Available at: http://lup.lub.lu.se/luur/download?func=downloadFile&recordOId=1556387&fileOId=15639 72 (Accessed: 28 February 2017).

Bourdieu, P. (2011) ‘The Forms of Capital (1986)’, in Szeman, I. and Kaposy, T. (eds.) Cultural Theory: An Anthology. West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 81–93.

Briskman, L. (2013) ‘Technology, Control, and Surveillance in Australia’s Immigration Detention Centres’, Refuge, 29(1), pp. 9–19.

Brunwasser, M. (2015) A 21st-century migrant’s essentials: Food, Shelter, Smartphone. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2015/08/26/world/europe/a-21st-century-migrants-checklist- water-shelter-smartphone.html?partner=rss&emc=rss&_r=2 (Accessed: 28 February 2017).

Cheung, S.Y. and Phillimore, J. (2013) ‘Social Networks, Social Capital and Refugee Integration’, Research Report for Nuffield Foundation.

Cogan, A. (2016) ‘How Technology is affecting the Refugee Crisis’, Mercy Corps (October).

Dekker, R. and Engbersen, G. (2013) ‘How Social Media Transform Migrant Networks and Facilitate Migration’, Global Networks, 14(4), pp. 401–418.

Diaz, V. (2014) ‘Legal Challenges of Biometric Immigration Control Systems.’ Mexican Law Review, 7(1), pp.3-30.

European Migration Network (2016) The Use of Social Media in the Fight Against Migrant Smuggling. Available at: http://www.emn.lv/wp-content/uploads/emn-informs- 00_emn_inform_on_social_media_in_migrant_smuggling.pdf (Accessed: 27 February 2017).

Facebook (2016) لطالبي†اللجوء†والهجرة†الشرعية†وغير†الشرعية†الى†اي†دولة†سوريين†حصر†اً†. Available at: https://www.facebook.com/%D9%84%D8%B7%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%A8%D9%8A-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%84%D8%AC%D9%88%D8%A1- %D9%88%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%87%D8%AC%D8%B1%D8%A9- %D8%A7%D9%84%D8%B4%D8%B1%D8%B9%D9%8A%D8%A9- %D9%88%D8%BA%D9%8A%D8%B1%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%B4%D8%B1%D8%B9%D9%8A%D 8%A9- %D8%A7%D9%84%D9%89-%D8%A7%D9%8A-%D8%AF%D9%88%D9%84%D8%A9- %D8%B3%D9%88%D8%B1%D9%8A%D9%8A%D9%86- %D8%AD%D8%B5%D8%B1%D8%A7%D9%8B-156119081253687/ (Accessed: 28 February 2017).

Farraj, A. (2011) ‘Refugees and the Biometric Future: The Impact of Biometrics on Refugees and Asylum Seekers.’ Colombia Human Rights Law Review, 42(891), pp.892- 992.

Fimyar, O. (2008) ‘Using Governmentality as a Conceptual Tool in Education Policy Research.’ Educate, pp.3-18.

Foucault, M., Fontana, A. and Burchell, G. (2009) Security, Territory, Population: Lectures at the Collège de France, 1977-1978. Edited by Michel Senellart and Francois Ewald. New York: Picador/Palgrave Macmillan.

Frouws, B., Phillips, M., Hassan, A. and Twigt, M. (2016) Getting to Europe the ‘WhatsApp’ Way: The Use of ICT in Contemporary Mixed Migration Flows to Europe. Available at: http://regionalmms.org/images/briefing/Social_Media_in_Mixed_Migration.pdf(Accessed: 28 February 2017).

Gillespie, M., Ampofo, L., Cheesman, M., Faith, B., Iliadou, E., Issa, A., Osseiran, S. and Skleparis, D. (2016) Mapping Refugee Media Journeys Smartphones and Social Media Networks. Available at: http://www.open.ac.uk/ccig/sites/www.open.ac.uk.ccig/files/Mapping%20Refugee%20Media%20Journeys%2016%20May%20FIN%20MG_0.pdf (Accessed: 17 February 2017).

Granovetter, M. (1983) ‘The Strength of Weak Ties: A Network Theory Revisited.’ Sociological Theory, 1, p.201.

Gray, C. (2017) Is your app the best way to help refugees? Improving the collaboration between humanitarian actors and the tech industry. - UNHCR Innovation. UNHCR Innovation. Available at: http://www.unhcr.org/innovation/app-best-way-help-refugees-improving- collaboration-humanitarian-actors-tech-industry/ [Accessed 23 Mar. 2017].

Hammerstad, A. (2015) ‘The Rise and Decline of a Global Security Actor: UNHCR, Refugee Protection and Security’, Journal of Refugee Studies, 28(1), pp. 135–136.

Haug, S. (2008) ‘Migration Networks and Migration Decision-making’, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 34(4), pp. 585–605.

Holmes, S.M. and Castaneda, H. (2016) ‘Representing the “European Refugee Crisis” in Germany and beyond: Deservingness and difference, life and death’, American Ethnologist, 43(1), pp. 12– 24.

Jacobsen, K.L. (2015) ‘Humanitarian Biometrics’, in Jacobsen, K.L. (ed.) Routledge Studies in Conflict, Security and Technology. Oxon: Routledge, pp. 57–87.

Katz, E., Blumler, J.G. and Gurevitch, M. (1973) ‘Uses and Gratifications Research’, The Public Opinion Quarterly, 37(4), pp. 509–523.

King, R. (2013) ‘Theories and Typologies of Migration: An Overview and a Primer’, Willy Brandt Series of Working Papers in International Migration and Ethnic Relations, 3(12).

Kunz, E.F. (1973) ‘The Refugee in Flight: Kinetic Models and Forms of Displacement’, The International Migration Review, 7(2), pp. 125–146.

Kyle, D. and Koslowski, R. (2011) Global Human Smuggling. 1st ed. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Latonero, M. (2012) The Rise of Mobile and the Diffusion of Technology-Facilitated Trafficking. Available at: https://technologyandtrafficking.usc.edu/files/2012/11/USC-Annenberg- Technology-and-Human-Trafficking-2012.pdf (Accessed: 27 February 2017).

Lev-On, A. (2011) ‘Communication, Community, Crisis: Mapping Uses and Gratifications in the Contemporary Media Environment’, New Media & Society, 14(1), pp. 98–116.

Manjoo, F. (2016) For Millions of immigrants, a common language: WhatsApp. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2016/12/21/technology/for-millions-of-immigrants-a-common- language-whatsapp.html (Accessed: 28 February 2017).

Massey, D.S. (1994) ‘The Social Contract the Social and Economic Origins of Immigration’, The Social Contract, pp. 183–185.

Nadig, A. (2002) ‘Human Smuggling, National Security, and Refugee Protection’, Journal of Refugee Studies, 15(1), pp. 1–25.

Palloni, A., Massey, D.S., Ceballos, M., Espinosa, K. and Spittel, M. (2001) ‘Social Capital and International Migration: A Test using Information on Family Networks’, American Journal of Sociology, 106(5), pp. 1262–1298.

Papadopoulou, A. (2004) ‘Smuggling into Europe: Transit Migrants in Greece.’ Journal of Refugee Studies, 17(2).

Petermann, T. (2007) ‘Biometrics at the Borders- The Challenges of a Political Technology.’ International Review of Law, Computers & Technology, 20(1-2), pp.149-166.

Postman, N. (1992) The Surrender of Culture to Technology. In: N. Postman, ed., Technopoly, 1st ed. New York: Vintage Books.

Pugliese, J. (2010) Biometrics: Bodies, Technologies, Biopolitics. 1st ed. New York: Routledge.

Rizvi, K. (2015) ‘What’s in my Bag? Uprooted’, Medium (September).

Rouse, A. (2015) ‘Social Media, SMS Outreach to Refugees’, UNHCR Innovation.

Ryan, L. (2008) Social Networks, Social Support and Social Capital: The Experiences of Recent Polish Migrants in London. Sociology, [online] 42(4), pp.672-690. Available at:

http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0038038508091622 (Accessed 15 Mar. 2017).

Scheel, S. and Ratfisch, P. (2013) ‘Refugee Protection meets Migration Management: UNHCR as a Global Police of Populations’, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 40(6), pp. 924–941.

Scottish Refugee Council, (2016) Refugees, Mental Health and Stigma in Scotland. Policy Briefing. Available at: http://www.scottishrefugeecouncil.org.uk/assets/0001/1369/Anti-stigma_briefing_FINAL.pdf (Accessed 16 Mar. 2017).

Shacknove, A.E. (1985) ‘Who is a Refugee?’, Ethics, 95(2), pp. 274–284.

Spittel, M. (1998) ‘Testing Network Theory through an Analysis of Migration from Mexico to the United States’, Center for Demography and Ecology University of Wisconsin-Madison, 99.

Stein, B. (1980) The Refugee Experience: Defining the Parameters of a Field of Study. International Migration Review, 15(1).

The Refugee Experience (2017) Available at: http://www.forcedmigration.org/rfgexp/rsp_tre/video/tr_2.htm (Accessed: 26 February 2017).

Tomlinson, C. (2016) ‘People Smugglers use Facebook to Lure Migrants to Europe’, Breitbart London (December).

Wall, M., Otis Campbell, M. and Janbek, D. (2015) ‘Syrian Refugees and Information Precarity’, New Media & Society.

0 notes

Text

What are the effects of gender stereotyping on the international community’s understanding of war and its aftermath?

Introduction

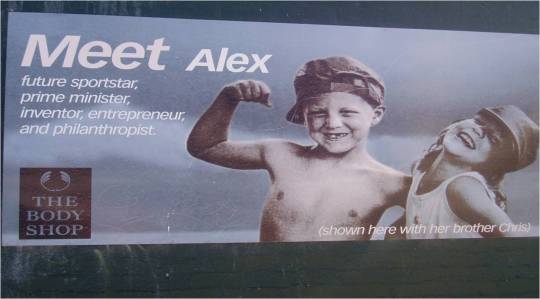

Men and women have been subject to gender stereotyping in arguably all aspects of their lives, but the debilitating effects of these are especially amplified when they influence the international community’s understanding of war and its aftermath. Gender stereotypes have influenced the conceptualization of men’s and women’s roles in war and its aftermath as being oppositional and disconnected. The belief in gender binaries shapes norms that inaccurately reflect the realities and interconnectedness of these roles. Even though legal and theoretical progress has been made at an international level, addressing the multiplicity of the gendered roles in contexts of conflicts, gender norms maintain the upper-hand in the execution of these agreements as well as the international community’s understanding. This paper will start by setting out the contextual concepts the question explores. It will then establish how gender stereotyping has framed women and how these have affected the international community’s perception of women’s roles during conflict. During war women are often understood as victims which ignores their role as perpetrators in violence, their combatant status and the vulnerabilities of their civilian status. During the aftermath, women’s role is recognized as being exclusively civilian, resulting in women being under or misrepresented in post-war processes. The following section commences by establishing gendered stereotypes attributed to men. It then focuses on the two effects that these have had on the international community’s understanding of these male stereotypes. Firstly, this understanding has led to men’s role during war being understood primarily as that of combatants which undermines the legal civilian status of some. Secondly, men’s assumed role as perpetrators and not victims of war can lead to inaccurate representations and care during the aftermath with specific reference to sexual violence. Overall this paper aims to problematize the international community’s understanding of men’s and women’s roles in war and its aftermath. Gender stereotypes can influence inaccurate comprehension of conflict and its potential solutions by ignoring the reality of the women’s and men’s roles.

Contextual Concepts

This section aims to provide a context to the concepts that will be used in the paper as the question is complex and the terminology malleable. Gender stereotyping is the practice of seeing women and men as opposites in terms of their behaviors, characteristics and norms (ONHCR, 2015). As Peterson (1992: 17), states, “gender is made up of interpretations of behavior culturally associated with sex differences”, and most importantly “gender shapes the implementation of international norms”. The international community is comprised of international organizations such as the UN and its bodies and agencies as well as NGOs and individual states (Annan, 1999). There are many ways to 2

interpret the understanding of the international community, however for this paper it is framed by the interpretation and implementation of international laws, security council resolutions and normative assumptions in practice. To set the scope of the paper, the understanding of war and its aftermath will be narrowed down to focus on the conceptualization of men’s and women’s roles during these phases of conflict, as their roles are pivotal in shaping conflict. War will be defined as “the open and declared conflict between armed forces of two or more states or nations” (O’Connell and Gardam, 2010) and the aftermath of war will include Disarmament, Demobilisation and Reintegration (DDR) initiatives as well as peacebuilding and rebuilding plans, post-war care and international trials. These two phases are distinct, and gendered stereotypes are both constructed and viewed differently in both stages. By defining the terms in these ways, a clear and precise context is framed, which will provide the foundation for this paper.

Women as victims and civilians in war and its aftermath

This initial section will start by defining what characteristics gender stereotyping has assigned to women. Gender stereotypes can range from culture to culture, however in the international community’s perspective these stereotypes can often adopt a negative and binary position. Women are often stereotyped by feminine characteristics incorporating both the idea of needing protection and merely being “beautiful souls” (Sjoberg and Peet, 2011). In the context of war, masculinity is viewed as that which defends the nation and femininity that which keeps it composed. Women are often presented as the antonyms of war and conflict, whereas they can be involved. They are understood as primarily being victims and civilians which neglects their agency, protection and role in peace facilitation. The next two paragraphs below will outline how gender stereotyping women in both the context of war and its aftermath has shaped the way the international community not only views but treats women as victims and civilians.

Gender stereotyping women by the above-mentioned attributes, has resulted in the international community considering women as victims and civilians during war. Hogg (2010: 222) asserts that, “normative recognition aligns gender directly with women and as active participants” it also and alters discourse because it does not regard women’s broader role in conflict. In both the legal documents and their implementation women are given a position as “object(s) of special respect”, which not only ignores their agency but reiterates their passivity and inability to be perpetrators of violence (Hogg, 2010: 225). Throughout history, as examples in Nazi Germany, Liberia and Sierra Leone have shown, women have either actively encouraged violence or took on positions as combatants (Heinrich Böll Foundation, 2010). By merely viewing women as victims, the 3

understanding of their actual roles in war are eschewed. Sjoberg and Gentry (2013), highlight women’s reduced political agency in these conflicts by arguing that women who have played a violent part in conflict “are reduced to mothers, monsters and whores” and not political agents. Conversely, women’s assumed “privileged status” of being civilian can also pose a risk (Sjoberg and Peet, 2011). In international law “civilians are persons who are not members of armed forces” (International Committee of the Red Cross, 2017). However, in practice this term is normatively assigned to women and children. According to Sjoberg and Peet (2011), the civilian immunity principle appears to the international community to protect the assumed weak and vulnerable women by providing a “protection racket.” Women, are often stereotyped as needing protection, and therefore by granting them the civilian status this is assumed to occur. Nevertheless, this limited understanding can lead to gender-subordination and the exploitation of these positions by warring parties. The immunity principle places women’s lives in greater danger in conflicts where civilian targeting, of almost exclusively women and children, is a normal part of tactics (Slim, 2008 and Sjoberg, 2006). By viewing women as victims and deserving of civilian status, because of their assumed gendered characteristics, their roles as perpetrators but also combatants are largely ignored by the international community, and their “exclusive” civilian status can pose a greater risk rather than a protective measure.

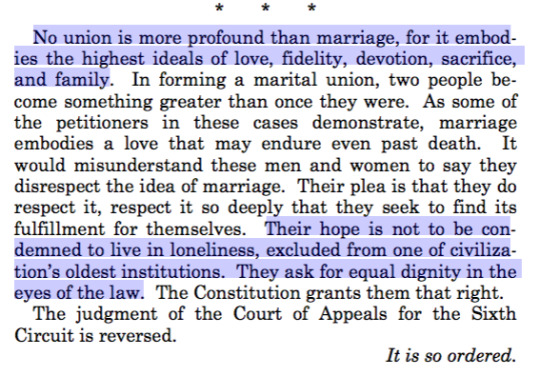

This next paragraph will explore how the civilian status, normatively attributed to women, has disregarded women’s roles and needs as combatants in the aftermath of wars, by looking at women’s roles in DDR programs, peace talks and country re-building initiatives. Gender stereotypes in DDR initiatives can disregard women’s active roles as combatants. This leads to important aspects being overlooked which reduces the effectiveness of such programs. Farr (2002: 20) uses the example of Sierra Leone, arguing that during the disarmament of the nation, women were smuggling arms, while men were involved in DDR programs. This example shows the importance of putting gender stereotypes aside by having the international community include women in DDR initiatives so as not to exclude these important actors. Not only do these initiatives disregard women as active combatants but they also disregard women as “post” combatants who might struggle with increased stigma and rejection (Hogg, 2010: 111). The Security Council Resolutions on gender in the 2000s contained key components actively addressing the need for women’s increased role in peace deliberations primarily in articles 2, 6, 7b and 16 of the 1325 Resolution (Security Council, 2000) and article 12 in the 1820 Resolution (Security Council, 2008), however women’s roles in DDR programs are not explicitly mentioned. Women’s combatant status has ineffectively translated into practices and still merely constitutes an “add and stir approach” (Krause and Enloe, 2015: 329). With regards 4

to women’ roles in the next stage, peace talks, Margaret Ward (2005: 12) emphasizes that even in these peace deliberations, women’s presences at peace-talks continue to be simple “token presences”. Although women are physically incorporated into peace talks, as the Arusha peace talks in Burundi and the Dayton peace talks in Bosnia have shown, their roles are still defined by gender stereotypes (Enloe, 2014). As Tickner (1992: 41) states, characteristics related to femininity are considered a burden when discussing matters relating to state building and security. An even more important time when women, due to their gender, are excluded is during the nation-building process. According to Daiva Stasiulis (1999), women’s representations as mothers and guardians of cultures in nationalist movements have often inhibited their engagement in reconstruction and constitution building. Constitution-building is one of the most important aspects of rebuilding a war-torn country, however women have in many cases been disregarded from joining which can be seen in the example of the Dayton Accords. The Dayton Accords in 1995, after the Bosnian genocide, included the creation of a new constitution but women were excluded from these talks and were unable to participate (Enloe, 2014). By conceptualizing women in a narrow framework their agency and influences are reduced which can be detrimental to rebuilding the country. What these points argue is that, gender stereotyping, generalizing all women as weak, passive and fragile, has led the international community to not fully understand the combatant role that women play fixating on the inherent gender binaries instead. Even though laws have been drafted encouraging the focus on women as combatants in post-war environments, these have hardly been translated into solid practices leading to women’s potentially valuable roles being overlooked.

Men as combatants and perpetrators