Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Audio

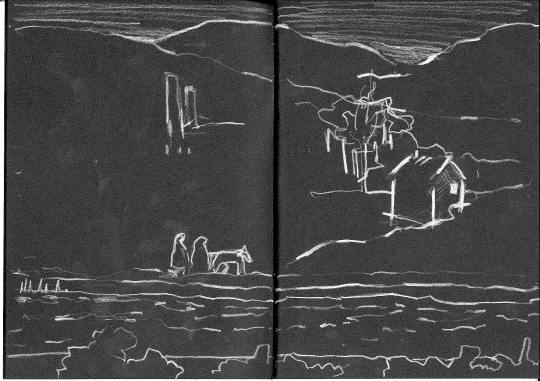

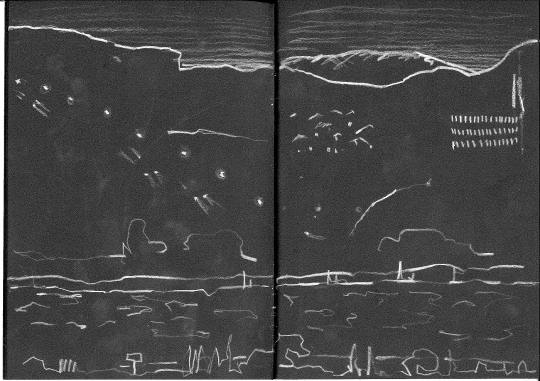

A grave, East of Wales and South of Manchester By Aidan Razzall

The children, clad in blood red football-shirts on cheap bikes and push-scooters seemed to be the only liquefiers of this place, snaking their adventure routes through the rigid grids of bungalows that stretched out like a gauze over the terrain- all pebble-dashed and double glazed.

The cul-de-sacs they rode on baked in the summer heat, undulating like the ventral scales of some tropical serpent, with their tarmac speed bumps and yellow painted borders rippling the scene ever so slightly. The scent of rubber bike tyre on the road, and the boiling, calculated burn of a parked car door under the palm of a child’s hand shrieked out from across the tranquil, seeing brow-beaten men in grey sweat shorts, disturbed from their afternoons in front of the television, barking harshly from across the slabbed drives, their eyes never leaving the screen for more than a flicker.

Uniformed and unified, the suburbia gently slumped out of sight to the fences of the rail tracks in the east. To the west, it reached a crescendo of red-brick workers terraces, the hot July sun beating off the windows and chimney pots and satellites, a technicolour refraction- as if it were a warning beacon, or a wormhole entrance to the long-closed industrial works that lay dormant on the fringes of town. The place heaved out an air of sadness, of histories forged and lost, of lives lived in simple loops, both in the mind and through the post-war visions of the architects who designed its streets, to which there were several municipal tributes, like brass cast statues of bespectacled and suited men in the Town square, clutching reams of paper with names like Boyce, Parkinson and Franklin, to the repetitions of their name on the road signs of Boyce Avenue, Franklin Street and Parkinson Drive, lined sparingly with beech trees sometimes.

The mud-brown clock tower of the council building that overlooked the statues, and of course the sprawl almost entirely, was in some ways a brief respite from the placid lines of 70’s new builds and terraces that shaped the general view. This was aside from the trio of high rise flats that shot up like screw-ends towards the train station, and the skeletal form of the football stadium which crouched sadly underneath their shadows, it’s crimson flags hanging limp in the summer.

Beyond aesthetics however, the town’s commerce was varied, with its population tending to the car dealerships, offices and either of the two supermarkets that peppered the roundabouts and distant retail parks. Cars and lorries, as if almost transfixed, routinely navigated the roads built by engineers of yesteryear, only stopping momentarily when some dog or flaccid polythene wrapping obstructed their path by virtue of feral nature or gentle breeze. People did walk, but only with dogs or zimmers or plastic bags of food from town. The canines and owners mainly made their journeys in the Franklin estate, and sometimes in the tower-blocks, although the zimmer-frames were clutched firmly in the tanned and ringed fists of pensioners in bungalow-land, and of course the bags of food were slung over the wrists of almost all demographics.

The place was towards the north of the town, emerging out of the tightly packed terraces, some red brick with protruding window ledges and netted curtains, and some coated in 30 years’ worth of unpainted plaster, or plaster painted in tooth-white or beige, but all sharing a unifying badge of honour- those newly fitted plastic doors that promised to be strong at first but seemed flimsy when someone kicked them in. It was an upward slope of green space, marshy in places, and encircled by two main roads that twinned at a traffic lights. It was said to be called the Brooklands, as at some point a natural spring or brook existed there- currently demonstrated by an iron meshed water-tunnel opening, halfway up the slope, that dripped water and oozed mud and roots and rusted rubbish-packets in the summer. Again a street sign, one with the dead end symbol on its left side, alluded to the name, although some of the letters had faded, and long grass concealed the others.

Panning away from the water-grate, the council had recently erected a public artwork next the tarmac footpath that split the Brooklands in two. It was black, maybe plastic, maybe some cross-polymer material and was forked in two like a fish tail or a split hair, so that from a distance it looked like an anachronism, some ancient totem from somewhere else, but on closer inspection the front side was engraved with little icons of hammers, drills, cogs and wheels, motifs of the town’s heritage. The reverse side was blank, aside from hardened gluts of chewing gum stuffed in the recesses by someone in need of a bin. Sometimes people walked past the sculpture, mainly occupants of the Mount Pleasant Women’s Refuge that directly overlooked it and the Brooklands itself.

At the summit of the slope, and with a view over the Refuge, the artwork, and the water-grate, sat the church. It was resplendent in red brick, with ash-grey slate roofs, and a copper-covered spire that had oxidised into a cerulean green over time. The town had a generally secular view, shaped by a life post industry and post-routine, but it was here that some sense of the Divine was present.

In the slow burn of summer, amongst the graves and tombs of the churchyard, a crowd of mourners walked in tandem towards a tiny grave, decorated with Disney toys and lurid flower arrangements, and a small, oval picture frame containing the photo of a child.

1 note

·

View note

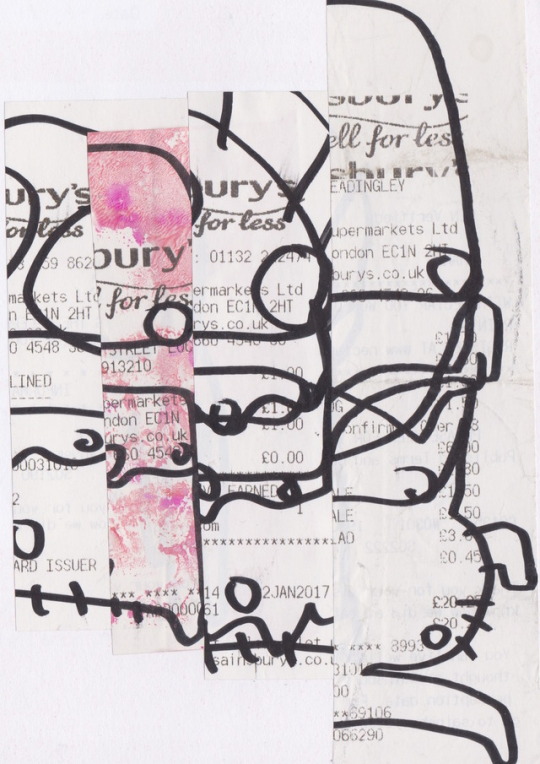

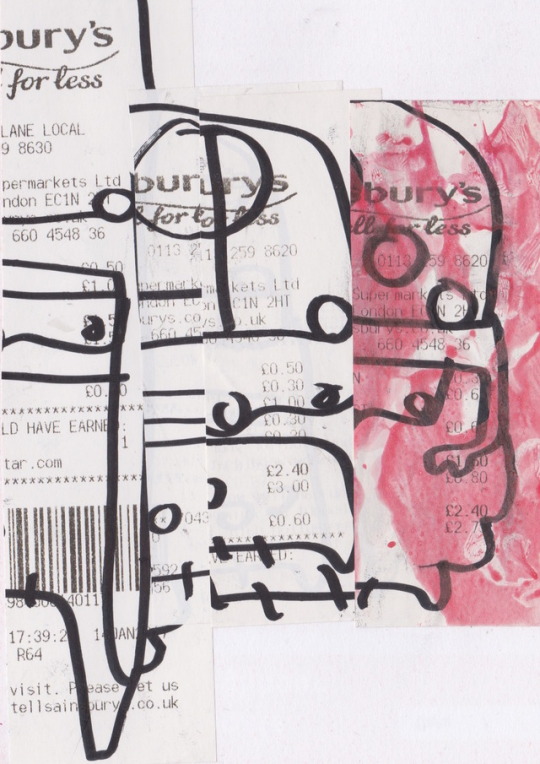

Photo

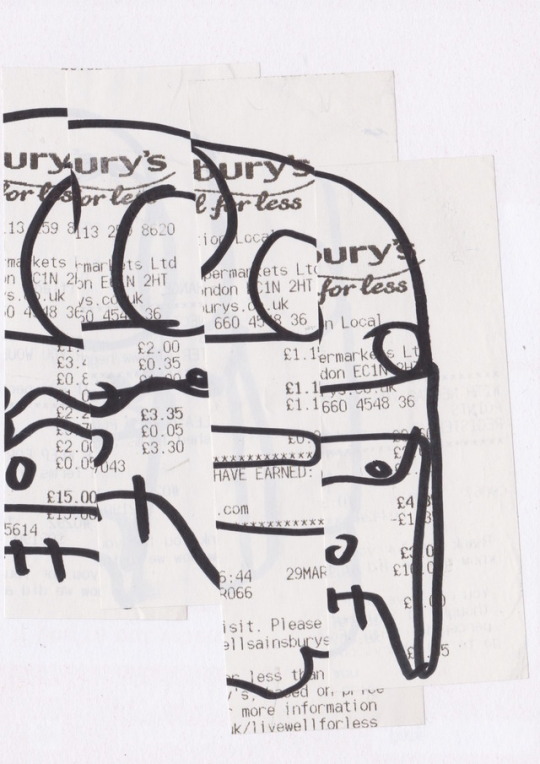

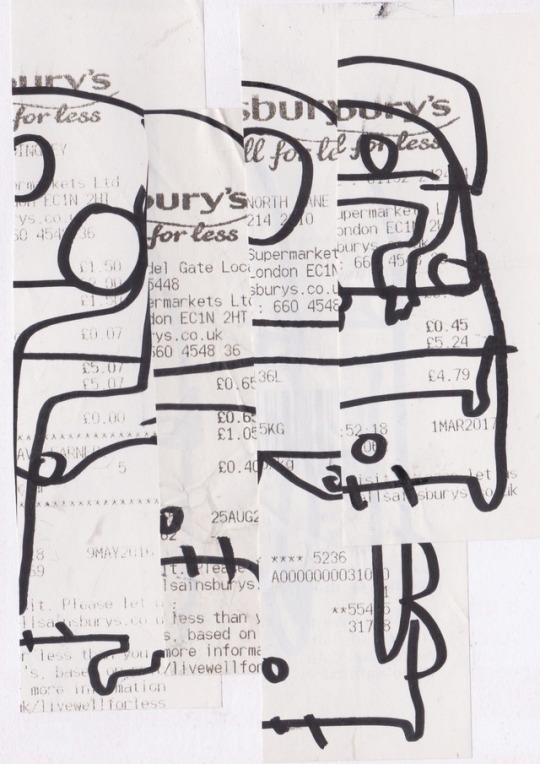

Flub issue #1

°east°

contributors:

Aidan Razzall

Déborah Gros

Erkembode

Nancy Day Hugues

0 notes

Text

! ! ! launch alert: new zine ! ! !

issue #1 of FLUB coming soon

20/03/2019

aka

1st day of spring

1 note

·

View note

Text

! ! ! launch alert: new zine ! ! !

issue #1 of FLUB coming soon

20/03/2019

aka

1st day of spring

1 note

·

View note