I write when my head hurts and eyes blurred, I collect things to write about when my heart breaks and mind cleared. this, is what I gathered.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Emerald Tablet

The Emerald Tablet, also known as the Smaragdine Table, or Tabula Smaragdina, is a compact and cryptic piece of the Hermetica reputed to contain the secret of the prima materia and its transmutation. It was highly regarded by European alchemists as the foundation of their art and its Hermetic tradition. The original source of the Emerald Tablet is unknown. Although Hermes Trismegistus is the author named in the text, its first known appearance is in a book written in Arabic between the sixth and eighth centuries. The text was first translated into Latin in the twelfth century. Numerous translations, interpretations and commentaries followed.

The layers of meaning in the Emerald Tablet have been associated with the creation of the philosopher's stone, laboratory experimentation, phase transition, the alchemical magnum opus, the ancient, classical, element system, and the correspondence between macrocosm and microcosm.

Textual history

The text of the Smaragdine Tablet gives its author as Hermes Trismegistus ("Hermes the Thrice-Greatest"), a legendary Hellenistic[1] combination of the Greek god Hermes and the ancient Egyptian god Thoth.[2] Despite the claims of antiquity, it's believed to be an Arabic work written between the sixth and eighth centuries.[3] The oldest documentable source of the text is the Kitāb sirr al-ḫalīqa (Book of the Secret of Creation and the Art of Nature), itself a composite of earlier works. This volume is attributed to "Balinas" (or Pseudo-Apollonius of Tyana) who wrote sometime around the eighth century.[4] In his book, Balinas frames the Emerald Tablet as ancient Hermetic wisdom. He tells his readers that he discovered the text in a vault below a statue of Hermes in Tyana, and that, inside the vault, an old corpse on a golden throne held the emerald tablet.[5]

Following Balinas, an early version of the Emerald Tablet appeared in Kitab Ustuqus al-Uss al-Thani (Second Book of the Elements of Foundation) attributed to Jabir ibn Hayyan.[6] The Smaragdine Tablet was first translated into Latin in the twelfth century by Hugo of Santalla.[7] The text is also in an enlarged thirteenth century edition of Secretum Secretorum (also known as Kitab Sirr al-Asrar).

The tablet text

A translation by Isaac Newton is found among his alchemical papers that are currently housed in King's College Library, Cambridge University.[8]

Tis true without error, certain & most true.

That which is below is like that which is above & that which is above is like that which is below to do the miracles of one only thing

And as all things have been & arose from one by the [meditation] of one: so all things have their birth from this one thing by adaptation.

The Sun is its father, the moon its mother, the wind hath carried it in its belly, the earth is its nurse.

The father of all perfection in the whole world is here.

Its force or power is entire if it be converted into earth.

Separate thou the earth from the fire, the subtle from the gross sweetly with great industry.

It ascends from the earth to the heaven & again it descends to the earth & receives the force of things superior & inferior.

By this means you shall have the glory of the whole world

& thereby all obscurity shall fly from you.

Its force is above all force. For it vanquishes every subtle thing & penetrates every solid thing.

So was the world created.

From this are & do come admirable adaptations whereof the means (or process) is here in this. Hence I am called Hermes Trismegist, having the three parts of the philosophy of the whole world

That which I have said of the operation of the Sun is accomplished & ended.

Theatrum Chemicum

Another translation can be found in Theatrum Chemicum, Volume IV (1613), in Georg Beatus' Aureliae Occultae Philosophorum:[9][10]

This is true and remote from all cover of falsehood

Whatever is below is similar to that which is above. Through this the marvels of the work of one thing are procured and perfected.

Also, as all things are made from one, by the [consideration] of one, so all things were made from this one, by conjunction.

The father of it is the sun, the mother the moon. The wind bore it in the womb. Its nurse is the earth, the mother of all perfection.

Its power is perfected. If it is turned into earth.

Separate the earth from the fire, the subtle and thin from the crude and [coarse], prudently, with modesty and wisdom.

This ascends from the earth into the sky and again descends from the sky to the earth, and receives the power and efficacy of things above and of things below.

By this means you will acquire the glory of the whole world,

And so you will drive away all shadows and blindness.

For this by its fortitude snatches the palm from all other fortitude and power. For it is able to penetrate and subdue everything subtle and everything crude and hard.

By this means the world was founded

And hence the marvelous conjunctions of it and admirable effects, since this is the way by which these marvels may be brought about.

And because of this they have called me Hermes Tristmegistus since I have the three parts of the wisdom and philosophy of the whole universe.

My speech is finished which I have spoken concerning the solar work

Original edition of the Latin text. (Chrysogonus Polydorus, Nuremberg 1541):

Verum, sine mendacio, certum et verissimum:

Quod est inferius est sicut quod est superius, et quod est superius est sicut quod est inferius, ad perpetranda miracula rei unius.

Et sicut res omnes fuerunt ab uno, meditatione unius, sic omnes res natae ab hac una re, adaptatione.

Pater eius est Sol. Mater eius est Luna, portavit illud Ventus in ventre suo, nutrix eius terra est.

Pater omnis telesmi[12] totius mundi est hic.

Virtus eius integra est si versa fuerit in terram.

Separabis terram ab igne, subtile ab spisso, suaviter, magno cum ingenio.

Ascendit a terra in coelum, iterumque descendit in terram, et recipit vim superiorum et inferiorum.

Sic habebis Gloriam totius mundi.

Ideo fugiet a te omnis obscuritas.

Haec est totius fortitudinis fortitudo fortis, quia vincet omnem rem subtilem, omnemque solidam penetrabit.

Sic mundus creatus est.

Hinc erunt adaptationes mirabiles, quarum modus est hic. Itaque vocatus sum Hermes Trismegistus, habens tres partes philosophiae totius mundi.

Completum est quod dixi de operatione Solis.

Influence

In its several Western recensions, the Tablet became a mainstay of medieval and Renaissance alchemy. Commentaries and/or translations were published by, among others, Trithemius, Roger Bacon, Michael Maier, Aleister Crowley, Albertus Magnus, and Isaac Newton. The concise text was a popular summary of alchemical principles, wherein the secrets of the philosopher's stone were thought to have been described.[13]

The fourteenth century alchemist Ortolanus (or Hortulanus) wrote a substantial exegesis on The Secret of Hermes, which was influential on the subsequent development of alchemy. Many manuscripts of this copy of the Emerald Tablet and the commentary of Ortolanus survive, dating at least as far back as the fifteenth century. Ortolanus, like Albertus Magnus before him saw the tablet as a cryptic recipe that described laboratory processes using deck names (or code words). This was the dominant view held by Europeans until the fifteenth century.[14]

By the early sixteenth century, the writings of Johannes Trithemius (1462–1516) marked a shift away from a laboratory interpretation of the Emerald Tablet, to a literal approach. Trithemius equated Hermes' one thing with the monad of pythagorean philosophy and the anima mundi. This interpretation of the Hermetic text was adopted by alchemists such as John Dee, Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa and Gerhard Dorn.[15]

C.G. Jung identified The Emerald Tablet with a table made of green stone which he encountered in the first of a set of his dreams and visions beginning at the end of 1912, and climaxing in his writing Seven Sermons to the Dead in 1916.[citation needed] Historians of science, Eric John Holmyard (1891-1959) and Julius Ruska (1867-1949) also studied the tablet in the twentieth century. Because of its longstanding popularity, the Emerald Tablet is the only piece of non-Greek Hermetica to attract widespread attention in the West.

1 note

·

View note

Text

POINTE SHOE BRANDS

Amber

Angel Dance

Angelo Luzio

Anniel

Antares

Aurora

B&M Danza

Ballerina

Balletique

Balletto

Bleyer

Bloch

Calidance

Cameo

Capezio

Capezio Brazil

Chacott

Colombo

Coppelia

D'Mauro Ballet

DanceField

Dancin’

Dansgirl

Danshuz

Deboule

Degas

DeVarona

Diamar

Ditas

Domyos

Dttrol

Ellis Bella

Etirel-Intersport

Evidence

Freddy

Freed

Fuzi

Gaynor Minden

Grishko

Gyffs by Carin

Inspire

Intermezzo

Jowy Queen

Karl-Heinz Martin

Kiev

Leo

LePapillon

Love For Dance

M.J.- Miguel Jorda

Meiguan

Menkes

Merlet

Mice Fiestas

Miguelito

Millenium

Minassian

Mirella

Mituri

Ms&J

Pauls

Prima-Soft

Principal

R-Class

Reart

Red Rain

Repetto

Rudolph

Rumpf

Russian Pointe

Salvio

Sansha

Schachtner

Siberian Swan

SoDanca

Sogei

Sonata of Singapore

Spanish Dancewear

Stanlowa

Stefanov

Studio Danza

Suffolk

Swiga

Sylvia

Teplov

Theatre Ballet

Ting

TKS

Triunfo

Vanassa

Vozrozhdenie

Wear Moi

Aloart of Italy

Fouette of Argentina

Büffel of Germany

Rommel E Halpe Ltda of Brazil

Fiorina of Venezuela

0 notes

Text

In contrast, materials in traditional pointe shoes by Freed, Capezio, Bloch, and Grishko are the same as 100 years ago, consisting of tightly packed layers of paper, cardboard, burlap, and/or fabric held together by glue. The material is compressed into an enclosure (toe box) that surrounds the dancers’ toes so that her weight rests on the platform. The shank is generally made of cardboard, leather, or a combination. With traditional materials, the shoes don’t last long. Grishko pointe shoes last between 4-12 hours, according to the company website. Given the long class/rehearsal/performance schedules, a typical dancer goes though many shoes in a year.

One major company that stands alone in using modern materials is Gaynor Minden. Rather than using paper, cardboard, and glue, Gaynor Minden shoes have modern materials for its shanks and boxes. Relative to traditional shoes, Gaynor Minden shoes last longer, are quieter, and have linings designed to reduce discomfort and limit injuries. Even with these positives, the shoes are controversial in some circles in the ballet world where tradition is cherished. This post takes a closer look at modern shoes, shedding light on the shoes and the behind the scenes controversy, a topic foreign to most ballet fans.

Gaynor Minden History

Eliza Minden is the Head of Design at Gaynor Minden having spent nearly a decade researching and developing pointe shoes, testing hundreds of prototypes in the process. A former avid amateur dancer, she had witnessed the introduction of high-tech materials into athletic equipment and believed from an early age that pointe shoes could also be improved with the use of modern materials. “I was outraged that dancers were expected to perform in such crummy shoes. Dancers are elite athletes. What they do is as difficult as what rock climbers and football players do. Yet they are expected to perform these athletic and artistic miracles in shoes made of paper and cardboard,” she says in the video below.

youtube

After graduating from Yale, she continued her search for a better shoe, slicing open dozens of pairs of shoes to learn more about the contents. In 1986, she discovered a shoemaker that specialized in special requests. After testing numerous versions, she began mass-producing shoes at a factory in Lawrence, Massachusetts in the late 1980s. The shoes use elastomerics (material that is able to resume its original shape when a deforming force is removed) rather than the traditional materials. The toe box and shank are made of one piece, covered by a shock-absorbing panel of high-density urethane foam, which adds protective cushioning throughout the shoe. The result is a shoe that is quieter, more durable, does not need to be broken in, and provides the dancer with more protection, possibly reducing injuries.

Eliza built a clientele by visiting cities with ballet schools, focusing her marketing on young dancers. Eliza and John Minden opened their first store in the Chelsea section of Manhattan in 1993, the same as their current store.

In addition to using modern materials, Gaynor Minden is unique among major pointe shoe manufacturers as it was started by a woman (with her husband John) in a male dominated industry: Bloch (Jacob), Capezio (Salvatore), Freed (Frederick), Grishko (Nicolay), and Sansha (Franck Raoul-Duval).

Academic Research

Eliza believed the modern materials would lead to a more durable shoe with more protection for the dancer. The limited academic research appears to confirm this. Cunningham et al. published a study in the Journal of Sports Medicine that examined the durability of pointe shoes. They ran the shoes through a mechanical stress and recorded the number of cycles before the shoes failed. The results are as follows:

Freed 8,868 Capezio 24,592 Grishko 71,817 Gaynor Minden 268,646

The results show that the Gaynor Minden shoes last 3.7 times longer than Grishko and 30 times longer than Freed. The authors conclude:

• “Fatigue testing of the shoes demonstrated one highly significant difference. The Gaynor Minden pointe shoe exhibited a fatigue range approximately 10 times higher than that of the other shoes tested. The static properties of the Gaynor Minden shoe were not so inordinately high as to predict the correspondingly high fatigue properties.” • “The high threshold of elastic limitation, evident by the long fatigue life, presents itself as the distinguishing mechanical characteristic of the Gaynor Minden pointe shoe.”

In an unpublished study led by a professor of Podiatric Medicine at Temple University, researchers studied 20 dancers using foot pressure assessment systems. They conclude:

• “Compared to the traditional pointe shoe, the synthetic pointe shoe demonstrates superior pressure absorption and motion control properties.” • “These results demonstrate that the incorporation of modern, synthetic materials improves the stability and alignment of the foot and ankle while decreasing strain and pressure on dancers’ feet which contribute to chronic stress injuries and disability.”

Academic studies on durability are nice, but does this result hold in the real world? I asked dancers how many shoes they go through in a year:

Gillian: I go through about 20 pairs in a Met season (eight week season) and a total of 50 pairs throughout the year.

Olivia: I go through about 30 pairs a season including when we go on tour. The Royal Ballet season starts in September and roughly ends in July. We do on average 130-140 shows per year and I’m involved in roughly 90% of the performances.

Bridgett: It’s hard to calculate, but during rehearsal periods I go through a pair about a pair every two weeks. I like to keep old shoes because I can often reuse them. During performances, the stage, rosin and pancake take their toll so I can go through a pair every two days.

Dancers wearing Gaynor Mindens go through far fewer shoes than dancers in traditional brands. I estimate that a typical NYCB dancer (most wear Freed) uses about 170 pairs of shoes a year. I estimate as follows: NYCB claims that it spends $600,000 a year on pointe shoes. An estimate of $70 per pair (Freeds retail for $80-$90, but ballet companies pay less than the retail price. In an NYCB video, the company shoe master mentions that the company pays $67.50 per pair) leads to 8,600 shoes a year. With approximately 50 female dancers, that comes to about 170 pairs per dancer a year. A typical ABT dancer uses 160 shoes a year (ABT spends $500,000 a year on pointe shoes, which leads to 7,100 pairs of shoes a year split among approximately 45 female dancers at a cost of $70 per shoe).

Shoe Cost

The cost savings from Gaynor Minden shoes is large. I assume a cost of traditional shoes to a ballet company of $70 and $90 for Gaynor Minden. I don’t know how much Gaynor Minden charges ballet companies, but I use an estimate of $90 (a pair of Gaynor Minden custom made shoes retails for $110).

_______________# Shoes Per year Cost Per Shoe Total Cost Traditional 160 $70 $11,200 Gaynor 40 $90 $3,600

Difference $7,600

The total cost savings of Gaynor Minden shoes over traditional shoes is $7,600 per year per dancer. Major ballet companies like The Royal Ballet and ABT have between 40-50 female dancers. With 45 dancers, the cost savings is about $340,000 a year.

The Controversy

Relative to traditional shoes, Gaynor Minden shoes last longer, are quieter, and have more protection designed to reduce discomfort and limit injures. What’s not to like?

Plenty in the traditional ballet world, where change is difficult to deal with. Despite the advantages of the shoes, some dislike the notion of modern materials in pointe shoes and the shoes were very controversial when they first came out, with questions regarding the look of the shoe and whether they were appropriate for high-level dance.

Kevin Conley of The New Yorker has a great 2002 piece on the pointe shoe controversy. The article has a number of rhetorical jabs at Gaynor Minden shoes from NYCB associated individuals. Since the 1960s, NYCB dancers have predominately worn Freed pointe shoes.

• Merrill Ashley, a former NYCB Principal Dancer finds the shoes “…appalling, quite frankly.” She refuses to refer to Gillian by name, instead referring to her as “the principal dancer” in “one of the major companies.” She objects to the look of the shoe: “I just can’t imagine being a professional dancer and wearing those. Aesthetically, from the audience, they look bad.” • Former NYCB Principal Dancer Suki Schorer approached Gillian in class and asked, “Why do you wear those space-age shoes?” • Katy Keller, a physical therapist for NYCB says about the shoes: “For the slightly less proficient dancer, the amateur, the student, it’s a great thing to have facilitated balance. But professionals don’t necessarily want that.”

A lot has changed since 2002 and the controversy has dissipated as more stars have adopted the shoes. In addition to Gillian, Olivia, and Bridgett, Alina Cojocaru (English National Ballet), Yekaterina Kondaurova (Mariinsky), Anastasia Matvienko (Mariinsky), Evgenia Obraztosva (Mariinsky), Alina Somova (Mariinsky), and Zvetlana Zakharova (Bolshoi), are currently wearing the shoes. Given that lineup, it’s hard to argue the shoe is not for high-level dancers. Moreover, teachers and artistic directors recommending the shoes on the Gaynor Minden website include Maria Calegari, Bart Cook, Melissa Hayden, Gelsey Kirkland, and Igor Zelensky. Noteworthy that all are former NYCB dancers.

Younger dancers are more willing to consider shoes with modern materials as the controversy fades. Katherine Higgins, an up and coming 18-year-old dancer at the Paris Opera Ballet and medalist at prestigious ballet competitions including Prix de Lausanne, Youth America Grand Prix, Helsinki, Varna, and Moscow, doesn’t perceive much controversy among younger dancers. “If any controversy pertaining to these shoes ever existed, it is rapidly vanishing. I remember hearing once from a teacher that Gaynors were a ‘cheater shoe’ but my experience has been just the opposite, as I have gained enormous strength since switching to Gaynor Minden. Obviously, some brands work better than others for a particular dancer. However I find that many ladies my age embrace the shoe and all of its positive characteristics.”

The health and safety benefits may resonate more with younger dancers over time as the old school philosophy summarized by Suki Schorer “Ballet isn’t about health. It’s an art form,” fades (quote from Conley article). It’s not just the arts that are sometimes slow to embrace improvements in safety, as the same tendency exists in sports. Hockey helmets are an example as some players avoided them, saying they reduced their field of vision; I suspect the real reason was an attitude that real men don’t wear helmets. Now all players wear them.

Currently, there are a few modern pointe shoe options. In early 2014, Bloch introduced a shoe with stretch fabric that allows the shoe to hug the foot when on pointe; with multiple patents and the latest in stretch materials, “one seamless, flawless line is now a reality” according to Bloch. According to Brio Body Wear, the stretch fabric back and outer split sole allow the shoe to “hug the foot when on pointe so the shoe looks better and feels more secure.” “The rest of the shoe is fairly conventional with the exception of the shanks that aren’t tacked together at the heel to allow them to snug up under the arch for better support from the shank,” says Brio.

There are niche start-up companies trying gain traction in the competitive pointe shoe industry such as Capulet and Flyte. According to Popular Science, the Capulet d3o shoe uses a thickening fluid used in products such as soccer balls and ski gear. The material provides flexibility under slow static movements, but stiffens on impact to protect the dancer’s toes. Flyte pointe shoes feature polymer compounds of varying strengths that give the shoe both rigidity and flexibility. Another innovation is the ribbon attachment mechanism that allows quick attachment of ribbons, according to the company website. Although innovative, I couldn’t find mention of any ballet company dancers wearing the shoes.

The market has been slow to embrace innovation, with few alternatives outside of Gaynor Minden. It will be interesting to see if more modern shoes will be introduced in the future as the stigma from wearing non-traditional shoes fades.

Dancers on Gaynor Minden

I asked Gillian, Bridgett, Olivia, and Katherine a few questions regarding their Gaynor Minden shoes, similar to the ones I asked NYCB’s Emily Kikta, Lara Tong and Miami City Ballet’s Rebecca King about their Freed shoes in my previous post. One constant across all the dancers is they have a strong attachment to their shoe brand.

What factors led you to choose Gaynor Minden shoes?

Gillian: I loved pointe shoes from the first moment of trying them on (right before my tenth birthday), but over time I started looking for shoes that were more consistent, fit me better, and made less noise. I tried every type of pointe shoe (Capezio, Grishko, Chacott, Freed, Repetto, etc.). At age 15, I first heard about Gaynor Minden shoes at the Jackson International Ballet Competition, and I’ve now worn them for twenty years!

Olivia: I have very narrow feet. As a result, I was getting a lot of foot injuries as my pointe shoes at the time were actually stopping me from moving naturally. I realized I was actually fighting with my pointe shoes rather than the shoes extending my line. I moved to Gaynor Minden and the fight stopped! That was eight years ago.

Bridgett: I suffered from a non-union stress fracture in my second metatarsal in 2009 and had bone graft surgery to repair it. I had to basically start from scratch to get back again. I switched from Freed to Gaynor Minden and was able to recover completely with no problems. I really believe that they keep my feet much healthier.

Katherine: Wearing Gaynors has made me rely on my own strength instead of a hard shank of a shoe. At first, it was a challenge to get used to what felt like less support, until I built up the correct strength to lift out of the shoe on my own. Gaynors especially helped me discover the control of rolling through demi-pointe, which added a whole new nuanced dynamic to my dancing. It has saved me much expense as well. Going from a pair of shoes a day to a pair of shoes a month was incredible.

When/why do you discard a pair of shoes?

Bridgett: When a pair does get worn down, it’s usually the shank that becomes soft for me. If I use rosin they can get dirty.

Gillian: My shoes last a very long time, but they eventually get dirty from studio, stage, and backstage floors. They generally seem a tiny bit more supportive when they are brand-new, but they never break or stop supporting me. I like knowing that my shoes are not going to give out half way through a performance!

Olivia: I know it’s time to throw a pair away when the back starts to buckle and toe box starts to wear down.

Are your shoes custom made to your specifications? What is the process for having custom made shoes?

Shoes are vital for dancers so it is not surprising that the shoes worn by dancers at ballet companies are custom made.

Olivia: A ballet shoe has to fit you like a glove, so every dancer needs a couple of tweaks here and there. For me I asked the makers to cut off a centimeter from the side of the shoes to highlight my arch rather than swallow it.

Bridgett: I have the heal and sides cut down a bit so that the shoe looks more streamlined on my foot. The process for having custom made shoes with Gaynor Minden is very easy. It’s best to go to a shop where the staff has trained Gaynor Minden shoe fitters. They will then tell the factory and order the shoes for you.

Gillian: The Gaynor Minden website shows 2,951 custom sizes to fit each dancer’s exact box, shank strength, vamp, and heel shape (see photo at the top of the post for shoe components). This is a unique feature, and it means that once you determine your exact needs and fit, each pair feels custom made. Over the years my feet have expanded slightly, and I went back to the Gaynor Minden boutique in Manhattan and tried a slightly bigger size. With the help of the fitter in the boutique, I ended up with shoes that have a box 3 (slightly tapered, but not extremely tapered or square), extra-flex shank (firm support but flexible enough to feel at ease rolling through and articulating my feet), and a sleek vamp and heel (which fit the shape of my foot best). My only custom feature that goes beyond the readily available options is that I wear a 9.75N because I was feeling in-between a 9.5N and 10N. The factory stamps “Made Expressly for G. Murphy” in the inside of my shoes.

In a single performance, do you use more than one pair of shoes?

The pointe shoes you see a dancer wearing at the beginning of a performance may not be the same pair she will wear at the end. Dancers in traditional shoes tend to change shoes as the toe box softens. While durability is not an issue for Gaynor Minden shoes, dancers may change shoes during a performance for a cleaner pair. Individual preferences govern here and there is no consistent practice among dancers.

Gillian: I often do switch pairs in ballets such as Swan Lake, Sleeping Beauty, and Don Quixote because I like to wear a clean pair-that I haven’t been sweating in-as much as possible throughout a full-length performance. However, many times I have kept the same pair throughout a show and even for multiple shows if they still look new. Either way, after performing in my shoes I will wear that pair for rehearsals for a week or two afterwards in rotation with other pairs. I also end up giving away a lot of shoes before they look overly worn for ABT’s autographed pointe shoe campaign.

Olivia: I constantly swap shoes throughout my working day. It all depends on my repertoire at the time. For a classical role I usually like a newer, hard shoe, but for a neo-classical role I tend to lean towards a softer shoe where I can feel the floor more.

Bridgett: I like to keep the same pair throughout a performance.

Does the same shoemaker produce shoes for a particular dancer?

For Freed and Capezio, yes, for Gaynor Minden, no (I don’t know about the other shoe companies). The Freed website has a list of shoemakers with nicknames (such as Butterfly Maker, Club Maker, number of years making pointe shoes, and personal interests). The level of attachment between a maker and a dancer can be very strong as described by Merrill Ashley in The New Yorker article:

I had Maker 17. Philly was his name. And he retired right before I did. I thought, Maybe this is a hint. I can’t get used to another maker. It’s like changing husbands. It’s…It’s you!

In contrast, with Gaynor Minden, shoe orders go to the manufacturing plant and a number of makers can work on the shoe.

Bridgett: The greatest thing about Gaynor Minden is that every shoe is the same and you know exactly what to expect every time. There is no worry about having to make do with a bad pair or if your “maker” leaves. It takes so much stress out of a dancer’s life. Also on a side note…they last longer so it means less sewing!

Gillian: My favorite feature is the consistency of Gaynor Minden shoes. Once the specifications of the order are fully determined, it is a relief to know that each pair is performance-ready.

Olivia: As the shoes are handmade you can sometimes get the odd pair which is a bit wonky or the vamp is too high. But this is very uncommon for Gaynor Mindens.

Does Dancing on Pointe Hurt?

There is no getting around it, dancing on pointe after many hours leads to bruised toes, blisters, and damaged toenails. An unglamorous side of ballet that dancers cover up with beaming smiles during a performance.

Olivia: We don’t get blisters like some think. We get terrible bruising on the nail and many corns. Sometimes my nails just drop off as they are so damaged! It’s the unglamorous side of ballet! I put tiny bits of silicon onto badly affected toes and I wrap each toe in tape to prevent blisters.

Bridgett: I take extra precautions with my toes to ensure I don’t get blisters. I use silicone toecaps on every toe and also wear ouch pouch toe pads. There’s nothing more distracting than having a bad blister when you’re trying to concentrate on dancing so I take the time each day to keep my toes healthy and pain-free.

Gillian: My toes are quite tough, thankfully, so it is rare that I will get a blister or feel discomfort aside from the usual body aches and pains of standing and dancing all day. Generally I don’t wear anything inside my pointe shoes (no toe pads, bandages, etc.), but if I do get a blister, I will use a small square of Second Skin and a band-aid.

0 notes

Text

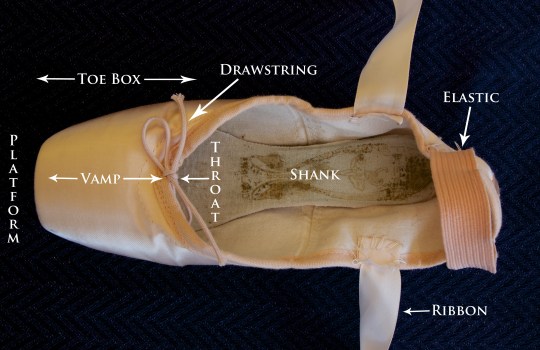

Anatomy of a pointe shoe

Here are photos of Lara’s pointe shoes. Click on the photos for a larger image.

Toe Box: the cup that encompasses the toes and ball of the foot Elastic: secures the shoe to the dancer’s foot Platform: the bottom of the toe box on which the dancer stands Ribbons: long satin type material that keeps the shoe more secure on the dancer’s foot Shank: the stiff insole that provides support under the arch Throat: the opening of the shoe Vamp: the section of the shoe that covers the top of the toes and foot

What are pointe shoes made of?

In traditional shoes, the toe box is made from tightly packed layers of paper, cardboard, burlap, and/or fabric held together by glue. The material is compressed into an enclosure (toe box) that surrounds the dancers’ toes so that her weight rests on the platform. The shank is generally made of cardboard, leather, or a combination. The outer material is a soft cloth called corset satin. The materials and methods of construction have not changed much in the last 100 years.

Gaynor Minden shoes are different from the rest. Gaynor Minden shoes have elastomerics (material that is able to resume its original shape when a deforming force is removed) for its shanks and boxes rather than the traditional materials of cardboard and paper, held together by glue.

What are the major pointe shoe brands?

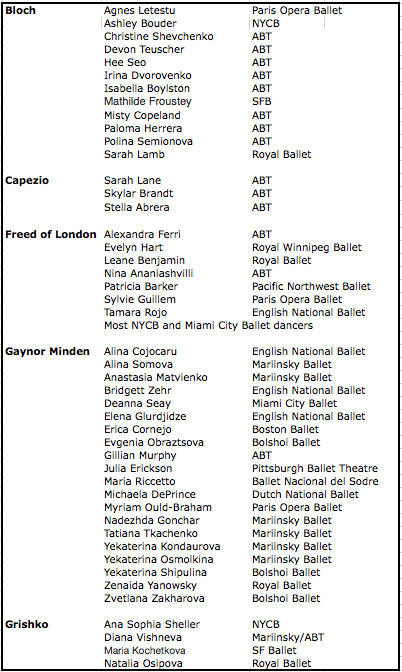

Why do dancers wear a particular brand? In some ballet companies, the preponderance of dancers wear a particular brand. Most NYCB and Miami City Ballet dancers wear Freed of London while dancers at the Australian Ballet wear Bloch shoes. At other companies like ABT, dancer preferences span the list of companies below. At companies without affiliations with shoe companies, dancers probably select shoes based on dancer recommendations, leading dancer endorsements in advertising, and trial and error in an effort to find the perfect shoe.

Bloch Bloch is an Australian company founded in 1932 by Jacob Bloch, a shoemaker who immigrated to Australia from Eastern Europe in 1931. Jacob loved music and dance; noticing a young girl struggling to stay en pointe, he promised he would make her a better pair of pointe shoes. He started making shoes in 1932 in Paddington, Sydney and his reputation for high-quality shoes grew as many ballet companies toured Australia during the 1930s, particularly Russian companies. Today, Bloch is headquartered in Sydney, Australia, with a European office in London.

Capezio Salvatore Capezio opened his shop near the old Metropolitan Opera House in New York City in 1887. He was only 17 years of age and his original business was to repair theatrical shoes for the Metropolitan Opera. In the late 1890s, he turned his attention to making pointe shoes. His reputation grew; Anna Pavlova purchased pointe shoes for herself and her entire company in 1910, helping Salvatore’s business. His success spread and by the 1930s, his shoes were used in many Broadway musicals and in the Ziegfeld Follies.

Freed of London Frederick Freed founded the company in 1929; before starting his company, Freed and his wife made ballet shoes at Gamba. After starting Freed, they worked from a basement in the Covent Garden section in London, the same site where the brand’s flagship store now stands. Today, Freed of London is a sister company of Japanese Dancewear company Chacott; both companies are owned by Japanese apparel company Onward Holdings. Freed of London sells in over 50 international markets through direct business partners and distributors.

Gaynor Minden Eliza and John Minden opened their first store in the Chelsea section of Manhattan in 1993. Eliza is the Head of Design at Gaynor Minden having spent nearly a decade of researching and developing a prototype shoe, testing hundreds of prototypes. A former avid amateur dancer, she had witnessed the introduction of high-tech materials into athletic equipment and believed that pointe shoes could also be improved with the use of modern materials. Gaynor Minden uses elastomerics for its shanks and boxes rather than paste and cardboard used in traditional shoes.

Grishko Nikolay Grishko, a businessman with a passion for ballet, founded Grishko in 1988, shortly after President Mikhail Gorbachev fostered the development of private enterprise in the USSR. At the time, Russian hand-made pointe shoes were not generally available to dancers outside of Russia. Nikolay capitalized on the demand for Russian shoes to create a global business in the manufacture and distribution of pointe shoes and other ballet gear. In 1989, the company introduced Grishko shoes to the U.S. ballet market.

Sansha Franck Raoul-Duval, a 25-year-old Frenchman with a passion for dance and Russian history, founded Sanscha in 1982. He developed a new type of ballet shoe, the split-sole ballet slipper, with a glove-like fit. Sansha now manufactures a range of dance shoes from ballet, jazz, hip-hop to flamenco, and ballroom to tap.

Who wears what?

How much do pointe shoes cost?

The retail cost of pointe shoes is presented in the table below as of early 2015. The price does not include the cost of ribbons, which are approximately $5.

Brand Types Lowest Highest

Bloch 21 $65 $80 Capezio 14 $52 $84 Freed 16 $78 $104 Gaynor Minden (GM) 1 $95 $95 GM Special Order 1 $110 $110 Grishko 10 $76 $81

How long do pointe shoes last?

The Grishko website estimates that the average life span of a pair of shoes is 4-12 hours of work, depending on the type of classes and the level of pointe work. Griskho recommends changing shoes after 45-60 minutes of work (30 minutes for dancers that perspire heavily) and letting them dry out for a minimum of 24 hours before using again.

On the other hand, Gaynor Minden shoes made of modern materials last on average about five times longer than traditional brands according to Cunningham et al. in The American Journal of Sports Medicine.

How many pointe shoes do ballet companies use in a year and at what cost?

Given that traditional shoes last between 4-12 hours, major ballet companies go through a lot of shoes. Pointe shoe expenses are a major cost of ballet companies and many companies have dedicated pointe shoe fundraising drives; much of the information below is from these appeals.

• ABT spends $500,000 a year on pointe shoes. I use an estimate of $70 per pair for ABT’s cost (ballet companies pay less than retail cost), which leads to 7,100 pairs of shoes a year split among approximately 45 female dancers. That’s about 160 shoes per dancer every year.

• NYCB spends $600,000 a year on pointe shoes. An estimate of $70 per pair leads to 8,600 shoes a year. With approximately 50 female dancers, that comes to about 170 pairs per dancer a year.

• The Royal Ballet: “Every year The Royal Ballet uses 12,000 pairs of shoes at a cost of 250,000 pounds,” (about $400,000). However, the 12,000 pairs of shoes probably includes men’s shoes and slippers. An estimate from The Guardian puts the total number of pointe shoes used at The Royal Ballet at 6,000-7,000 pairs a year.

• English National Ballet: English National Ballet uses 5,000 pointe shoes a year (information from video).

• The Australian Ballet: “Over 5,000 pairs of pointe shoes are used at a cost of more than $250,000. The Australian Ballet issues each female dancer with pointe shoes: corps de ballet and coryphée members receive two pairs per week, soloists and senior artists receive three pairs, and principal ballerinas receive six pairs. All of these shoes are hand-made to each dancer’s individual specifications.”

• The Birmingham Royal Ballet goes through “…over 4,000 pairs a year.”

• The Miami City Ballet uses 3,000 pairs of shoes a year.

Marianela Nuñez of The Royal Ballet discusses her pointe shoe use in The Telegraph: “During the day I can get through two pairs of shoes in rehearsals; if I’m dancing in a three-hour ballet, I use one pair per act, so three pairs can go in one night.” She wears Freeds.

Emily at NYCB explains that the number of shoes she uses in a season depends on what she is dancing. “The number of shoes I go through depends on the rep for that season. For instance, during Nutcracker I go through at least 2 pairs every day. Therefore in six weeks that’s at least 72 pairs! During our regular Winter and Spring seasons the count really varies because I may be rehearsing all day and performing all night or I may have the entire day off.”

Most major companies have a shoe master or manager to manage the process of recording dancer specifications, ordering the shoes, and coloring the shoes if necessary. The Birmingham Royal Ballet has a nice profile of its shoe master with a summary of his responsibilities.

Do professional dancers wear custom made shoes?

Most professional dancers wear custom or special order shoes. Freed offers special order shoes in which the dancer can specify the shoemaker, length, width, type of block, custom vamp, insole type, among other items. The Freed website has a list of shoemakers-all that have photos are men-with letters and nicknames (such as Butterfly Maker, Club Maker), number of years making pointe shoes, and personal interests.

Like most dancers at NYCB and Miami City Ballet, Emily, Lara, and Rebecca wear custom made Freed shoes and a common theme among the comments below is the great benefits of wearing custom shoes.

Emily: My shoes are custom made and I feel so lucky that we can do that here! My shoes are Freed Classics with the Bell maker. I don’t do many crazy customizations besides a little extra glue in the box and a little less satin on the sides so I don’t get any bunching on the sides of my feet.

Lara: I’ve worn shoes from many makers at Freed. I used to wear from another maker, but now I wear shoes from Fish and Crown makers.

Rebecca: At Miami City Ballet we all wear custom shoes. Our shoes can make or break our dancing (as hard as that may be to believe). If you have too much material on the top of your foot, you won’t be able to get all the way en pointe. If the bottom sole of the shoe is too soft, you will go too far over when you are en pointe. If the tip of the shoe is too soft, your shoes won’t last more than an hour. These are the sorts of things that are determined by each dancers’ individual foot. So the ability to have shoes customized really is invaluable to us.

I have worn Freed of London since I was a student. When I started dancing with Miami City Ballet as a student in the school, I was delighted to find that they provided me with shoes for performances. The first time I was presented with shoes from the company felt like Christmas to me. The shoe master offered me shoes that were in my size: special order Freed shoes that one of the principal dancers in the company could no longer wear. I was amazed by the world of shoe customization! It seemed as if my options were limitless. They are in fact so limitless that eight years later I find myself continuing to chase the mythical “perfect” shoe.

Pointe shoe brands have different representatives who travel around the country helping dancers find their perfect shoe. I wouldn’t say that they try to convince dancers to switch but if the dancer is interested, they help them with their customization and other issues.

Here is a video from Rebecca’s website on how Marie fits shoes for dancers:

youtube

Are all custom made shoes the same?

You might think that all custom made shoes are the same, but they are not, with slight differences across makers that only a dancer can detect. Interestingly, shoes that are made by the same maker can vary from shoe to shoe. That was what Rebecca, Ashley Bouder, and Emily are referring to when they say that some shoes are “good” and “bad.”

Rebecca: I wear custom made Freed shoes, and sometimes a shipment of shoes will come in a little different than a pervious one. Amazingly these small inconsistencies make a big difference.

Emily: Since all Freed Classics are handmade, there are definitely going to be variations. Usually you can tell before you put them on if they are going to be good or bad shoes. But most of the time you can make a shoe work for something even if it is a little weird!

Ashley Bouder, NYCB, in an interview with Pointe Magazine: Because they are handmade, Bouder’s shoes aren’t all identical. Some pairs arrive looking as if they won’t work well at all. “I pick out the good pairs and wear those first, but I end up wearing all of them anyway,” she says. “You can fix anything on a shoe. If there’s a lump on top you just take a hammer, flatten it and glue it. You only have to wear them once.”

How do dancers break in their pointe shoes?

youtube

Emily: I break in all of my shoes the same way no matter if they will be used for a show or just rehearsal. I don’t do anything too crazy though: just a little glue in the tip, bend the top of my shank and take the nail out of the heel so it doesn’t stab me!

Rebecca: I usually save good shoes for performances. I find that I will try to wear my least favorite shoes for rehearsals and classes. I generally prefer shoes that are brand new, so to prepare them for a show, I usually will just wear them for one class. I have even been known to put brand new shoes on right before going on stage. Again this is all preference, and everyone is different.

Lara: I don’t use special shoes for performance. I always break in my shoes the same way-I step on the box to flatten it a little and then bend the shank. I used to take the nail out from the shank and split it apart from the bottom, but now I custom the shoe to not have a nail. Then for a show, I bang my shoes on the wall to make sure they’re not loud.

Ashley Bouder in Pointe Magazine:

Before wearing new shoes, Bouder steps on the box and works it with her hands, and bends the shank back and forth. She also reinforces the tips with glue inside the box. “I have a very specific place where I put in little bits of glue,” she says. “It makes all the difference in the world for me—it’s the difference between being able to turn and not being able to turn.”

The amount of glue varies for particular performances. “If I know I’ll be turning a lot on the same foot, such as doing 32 fouettés, I’ll put extra glue in that shoe,” she says. “Or for Rose Adagio I’ll put extra glue in the right shoe because I’ve got eight balances on that foot. If I’m doing something soft and pretty, I still add glue, but I don’t put extra glue and I make sure I bang them so that there’s no noise.”

She breaks in a new pair during class then puts them away for that evening’s performance. For rehearsal, she wears the shoes from the night before. Though she’s not sure how many pairs she wears in a season, Bouder typically uses one pair per performance, but if she’s dancing a full-length ballet such as Swan Lake, she’ll use at least two pairs in one night.

Do dancers wear more than one pair of shoes in a performance?

See those nice shiny pointe shoes a dancer is wearing at the beginning of a performance? Chances are the dancer will not be wearing the same pair at the end of the performance.

Rebecca: This really depends on what the evening entails. I find that for some ballets I need brand new shoes, while for others, I prefer ones that are a bit softer. I usually determine this based on the choreography: if there is a lot of pointe work or turns, I find that I need a very solid shoe, while something that involves more jumps call for softer shoes. So I often find myself changing shoes more out of preference than necessity.

Lara: Depending on the programs that night, I can use more than one pair. Sometimes I’ll wear a new pair for one program (like Serenade) and then sometimes an older pair that’s been worn a few times (like Princesses in Firebird).

Emily: My routine usually is to wear a different pair for each ballet I am performing that night. That way my shoes are never soggy or too dead by the time I get to the last ballet. This is very important since by 9:45 pm you’re pretty tired and may need a bit more support for the final ballet of the day.

Marianela Nuñez: As quoted in The Telegraph, Marianela uses one pair per act. In a full-length ballet such as Don Quixote, she goes through three pairs.

When do dancers discard a pair of shoes?

Lara: I discard a pair of shoes when the boxes are uneven because it’s dangerous to dance on; at that point, it’s too soft to give me adequate support. I think it’s very important for our longevity to have shoes that provide enough support.

Emily: This is definitely different for each dancer. For me, I usually need to discard my shoes once the right shank has died. That will always die first for me because my right foot is a little bit more flexible than my left!

Rebecca: Usually my shoes die first in the box.

When do dancers wear their pointe shoes in ballet class?

A dancer starts their day with ballet class. A ballet class generally lasts 90 minutes with the first part consisting of barre exercises and the second part center work consisting of adagio, petite and grande allegro. Some women wear their pointe shoes throughout ballet class while other wear slippers, which are made of leather or canvas, similar to what men wear. Practices among women differ as Emily, Lara, and Rebecca explain.

Rebecca: I wear pointe shoes for the entirety of class, every day. I used to wear flat shoes for barre and put my pointe shoes on for center, which is quite common. I would find that it would take my feet awhile to become warmed up enough to dance in the center, so I began putting my shoes on as soon as I step in the studio in the morning. This has been very beneficial to my pointe work and the strength in my feet and ankles.

Emily: Up until very recently, I would always wear my pointe shoes from the first plie of the day until the day was done. However, after dealing with some tendon issues, I’ve started wearing wool socks or flat shoes for barre. It gives my feet a slower warm up to make sure I don’t overstretch anything. I do prefer wearing pointe shoes at barre though, so I hope to one day get back to that! In the off season, I pretty much have the same routine with my shoes because it’s necessary to keep my feet acclimated to pointe shoes so I don’t get blisters.

Lara: It’s really up to each dancer, but I wear flat shoes for barre and pointe shoes for center. It’s nice to be able to roll through my feet early in morning without pointe shoes to give my body a chance to warm up. When I’m not performing, I usually try to take class to stay in shape and that’s when I’ll wear my shoes. There are some girls who like to wear their pointe shoes around at home to prevent their feet from weakening too much.

Does wearing pointe shoes hurt?

Emily: At this point I am pretty used to wearing pointe shoes for long periods of time. Unless we are doing a ballet like Swan Lake with a lot of bourrees, my toes don’t hurt that much. More than anything, my arches cramp before my toe nails hurt. I can’t say that this is a better pain though! It still is quite uncomfortable.

Lara: Yes, my toes definitely hurt after wearing pointe shoes for long period of time, even after years of dancing and forming callouses. I think it’s only natural because pointe shoes only provide a very small and tight space that puts pressure on my feet in ways that aren’t meant to happen to the body. Although I’m used to the feeling of pointe shoes, I still get aches and bruised toe nails. To limit discomfort, I soak my feet in epsom salts and elevate/ice to reduce swelling. I personally find 2nd Skin to be a miracle worker when my feet hurt.

0 notes

Text

The Guilty Black lovers bring out the most thrilling sides of each other: alone they are magnificent, together irrepressible. Fearless in their passion, they are brazen, shameless, unpredictable – ready for each and every explosive encounter. Their attraction is instinctive: they go where they sense danger and each other. Too much is never enough for our young hedonists, who drive each other to live life to the fullest. Again and again, they give in to pleasure and the excitement of breaking the rules.

0 notes

Text

The “in” words.

A donf

Allôôôôôôôôôôôôô

C’est trop….

C’est un truc de…

J’adore…

J’ai un plan

J’hallucine

J’rigole

Je gère

Merciiii

No problem

Pas de soucis

Popular but use sparingly.

C’est chanmé

C’est swag

Je suis frais

Je suis trop dègue

Je vais chiller

C’est ma best

Ça va le faire…

Not that great. Avoid. Use jokingly and maybe not in polite company.

GraaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaVe

J’entends bien

Steuplait…

Tu me saoules

Outdated. Has-been.

C’est cool

C’est l’angoisse

C’est ma bff

Ça craint!

Je reve

Frérot

A donf. Backwards slang for à fond. Expression used mockingly by teens to claim they’re “giving it all”, they’re working “flat out”, they’ve got “the pedal to the metal”. The last time I heard one of my kids use this expression, it was “But I’m studying, Je suis à donf.” In fact he was sprawled across the bed.

Allôôôôôôôôôôôôôôôôôôôô !!!!!!!!!! Definitely not the same Allô the average Frenchman uses to answer the phone. You might say this Allô is for a “wake-up call”. It’s like saying, “Get real!” Ca craint: Problemo! C’est chanmé. Originally backwards slang for méchant. In Teenspeak it means “wicked awesome”. Ça va pas le faire… No way this is gonna work, dude! C’est ma best. He/she’s my best friend. C’est ma bff. She’s/he’s my Best Friend Forever. (If you’re still saying this, you’re already behind the times.). C’est swag. From the English word swagger. Classy! Superior taste and breeding, that others will want to imitate. C’est cool. It’s cool. C’est un truc de. Lazy talk when you can’t think of a better word. Like “thing” or “shit” in English: C’est un truc d’enfer / “cool stuff. ” Un truc de malade / “crazy shit”. Je suis frais. I’m cool. Not to worry. Frérot. New word to say buddy or pal. Instead of saying Bonjour, kids can might say Salut frérot. (Hi bro!) Graaaaaaaaaaaaaaave!!!!!! French Teenspeak for “Absofuckinglutely”. Often put at the end of a sentence to reaffirm something. Example: T’as aimé ma nouvelle recette de cookies ? Trop bons, graaaaaaaaaaaave. J’entends bien. I do understand. You don’t have to repeat yourself. J’ai un plan. I gotta plan. I got an idea where we can party, where we can hang out, maybe grab a bite. J’hallucine. Literally “I’m hallucinating” In other words “That’s nuts. It’s friggin’ crazy!” J’rigole. “non j’rigole” Means “Just joking”. Expect when your kid says this he may actually mean the opposite. A French teenager usually says this just after putting foot in mouth. Maman, j’ai pas mal dépassé mon forfait, non j’rigole »

Mom, I just realized I overspent… oops! Never mind! Just kidding! Je gère. I’m dealing with it. Meaning (believe it or not) I’m grown up enough to handle my allowance and my own cell phone plan… and what I do is none of your business. So don’t worry! T’inquiètes, je gère ! Je rêve. “Like am I dreaming or what!” Je suis trop dègue. “Dègue” is a contracted form of the French word for “disgusted”. In French Teenspeak, it actually means “I’m deeply disappointed”. If you fail an exam, you say J’ai eu une sale note, je suis trop dègue.» “Bummer, the grade she gave me really bites!” Je vais chiller. I’m gonna chill out.

0 notes

Text

1. Ça baigne ? Ça baigne !

When you first started learning French, you probably picked up quite quickly on that very useful question/answer pair: “Ça va ? Ça va!” The expression literally translates to “It goes?” “It goes!” but is used as a form of greeting, similar to, “How are you?” “Good.”

And yet, if you really want to sound in-the-know, this other question-answer pair is far more useful.

Ça baigne uses the verb baigner, meaning to bathe. Baigner is used non-idiomatically to refer to something submerged in a liquid. For example: Ça baigne dans de l’huile (It is bathed in oil). In fact, that’s likely where the expression comes from.

Some etymologists believe that the mid-20th century term comes from the idea of bathing in oil — something that’s quite fantastic for potatoes or pommes frites (french fries) — or even another kind of bathing altogether. Ça baigne is often associated with the beach, where not only do people se baignent, go for a dip, but are often themselves baignés (bathed) in oil — tanning oil, that is! Of course, today you don’t need to be swimming in anything in particular to use this expression which means ça va.

2. Arrête de te la péter.

This next expression is used to tell someone to stop being a show-off or stop bragging.

Before we delve into this expression, bear one thing in mind: you don’t want to use this one in front of anyone’s grandmother. Or really anyone’s mother. It’s not all that vulgar, but it’s definitely not for mixed company. The reason has a lot to do with the real meaning of the last word: pétermeans to fart.

You may now be asking yourself why there’s an idiomatic expression in French telling people not to fart on themselves. It’s a bit more complicated than that.

The clue is in that la that has snuck its way into the expression. The larefers to a noun now forgotten in the general use of the phrase — originally it referred to bretelle or suspender. In the 19th century, holding out one’s suspender and making it pète or snap against one’s chest was a way of punctuating a brag or show-offy comment. The expression is still used in its entirety in Québec.

If you want to use a similar expression in mixed company, try using Arrête de te vanter instead.

3. Je me casse.

This is a very familiar, bordering on rude way to say that you’re leaving somewhere. A bit like “I’m outta here!” It can also be used as a suggestion: On se casse ? (Should we get out of here?)

This expression can also be used as a sort of insult. To say “Casse-toi !” to someone means, “Get out of here !” or even “Piss off!” It’s definitely not an expression to be used around just anyone, but it can come in handy if you’re being harassed in the street. A well-placed “Casse-toi !” definitely gets the message across.

4. Il capte rien.

Astute French grammarians will see that the negator “ne” has been dropped from this phrase, as it is in most French slang expressions. This one means “He doesn’t understand anything,” or “He’s super out of it.” You can use it to describe an airhead or someone a few crayons short of a full box.

If you want to put even more emphasis on this expression, you can say, “Il capte trois fois rien.“ Though astute mathematicians will say that three times nothing is still nothing. French slang isn’t an exact science.

5. Laisse tomber.

Laisse tomber means “Let it go” or directly translated, “Let it fall.” It’s vaguely similar to the English “Drop it,” though the English expression is a bit more aggressive in intent than the French version. “Never mind” would be a more apt translation. Laisse tomber is a great expression to use when you realize that the person you’re talking to doesn’t understand what you’re saying and you’re tired of trying to explain… something that can happen frequently when you’re learning a language.

This expression has become so common in French that some prefer to use it in verlan, the French slang that consists of inverting syllables of certain words. In fact, verlan is verlan for l’envers, or the opposite. The verlan for laisse tomber is laisse béton, which becomes all the more amusing when you realize that béton also means concrete.

0 notes

Photo

L-AGALLERRIE coloring1274. soft babe (x)

Please, don’t claim as your own;

if you download/use favorite or reblog this post!

More resources on l-agallerrie!

438 notes

·

View notes