I joined because I like TMBG but I don't know what I'm doing here otherwise.

Last active 60 minutes ago

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

they might be dolls

i made some little wooden john-dolls.

66 notes

·

View notes

Photo

@ Maxwell’s//Hoboken, NJ

130 notes

·

View notes

Text

love it when tmbg photoshoots just look like this

198 notes

·

View notes

Text

"yeah, now which one of you guys is the one with the, uh, obsession about the World's Fair?"

JL: uh oh ... wow.

514 notes

·

View notes

Text

Decided to try and actually draw them again yayyy. Heres just the line art and also some doodles of my HCS sona :]

205 notes

·

View notes

Text

Just a screenshot.

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

( x )

78 notes

·

View notes

Text

Magnet interviews John Linnell!

At 10, my daughter has essentially discarded the kiddie version of They Might Be Giants. Like most pre-teen TMBG fans, she started with 2002’s No!, the Brooklyn duo’s initial foray into children’s music. She received her copy—signed by TMBG’s two Johns, Linnell and Flansburgh—as a Christmas gift. She listened to it a few times, then set it aside.

More recently, after a chance encounter with “They’ll Need A Crane,” she abruptly decided she’d be better served by their adult catalog. With my help, she promptly went about dissecting 1988’sLincoln and its 1990 follow-up, Flood, with the zeal of a kid running roughshod over her first PG-13 DVD.

For me, that’s meant fielding questions about “prosthetic foreheads” and seemingly benign couplets that defy the logic of basic human interaction—like, “I’m just tired and I don’t love you anymore/And there’s a restaurant we should check out … ”

“You can get a lot of distance by invoking the concept of poetic license,” says Linnell, when informed of my quandary. “Explain the concept to her. It’s a way of expressing things that don’t make sense—that are, in and of themselves, mysterious. That would be a way to dodge the question, I’d say. But I’m kind of thrilled that she’s so curious about it.”

Perhaps it’s poetic license that has seen TMBG through a voluminous series of ups, downs and holding patterns over its three decades in operation.

“We were very lucky in that we somewhat carelessly didn’t make the sort of compromises a lot bands attempted just to make a living,” says Linnell. “When we were in our 20s, we weren’t even that serious about making money. As a result, we sort of carved out this area where we were widely perceived as doing our own thing.”

Through it all, there’s been cheesy drum machines and wheezing accordions, unlikely MTV lionization, awkward attempts at becoming a real band, TV theme songs, multiplatinum sales, even a Grammy.

And, above all, there have been tunes—tons of ’em, delivered via vinyl, cassette, compact disc, download and the infamous Dial-A-Song. “We were locked in this terrible struggle with these machines that we used for Dial-A-Song,” says Linnell, explaining its unceremonious 2006 demise. (Though there’s now a cool TMBG iPhone app.) “We tried to switch over to a computer-based thing, and that was a disaster. It just miserably petered out.”

At last count, the TMBG tally is more than 300 album tracks—one of them as short as four seconds. Never mind the stray tunes from numerous EPs and compilations. But who’s counting? Not Linnell and Flansburgh. They’re just happy to still be viable so late in the game.

“It’s very hard to make money making any kind of music nowadays,” says Linnell. “I really have a hard time imagining how you’d do something like what we’re doing and still enjoy the middle-class lifestyle we’ve had for the last 30 years. Everything that’s happened for us in the music business has made us seem more acceptable to people—less of a UFO.”

Flansburgh offers this in the way of insight: “We’ve been lucky in that our muffler’s been dragging at various times, but we’ve never had to pull off the road.”

TMBG’s second adult album in five years and its 16th overall, Nanobots (Idlewild/Megaforce) boasts 25 new songs. And much like its big-boy predecessor, 2011’s Join Us, it could stand a little pruning, especially around a hindquarters saddled with prog-rock weirdness, disconcertingly abrupt swings in momentum and even a half-baked Pet Sounds homage (“Too Tall Girl”). Fortunately, the LP is front-loaded with hook-laden, high-energy TMBG—like “You’re On Fire,” (with an intro lick cribbed from the Jackson 5’s “ABC”), the dodgy (in the best sense) “Black Ops” and the conventional (but still bitchin’ and destined to kick ass live) rocker, “Lost My Mind.” “Circular Karate Chop” is giddy adolescent fun, and the title track has the same ratcheted-upfaux-theme-song flair that made “The Mesopotamians” (from 2007’s The Else) such a trip.

“Nanobots involves some of the laboratory-type stuff we’ve been doing since the beginning,” says Linnell. “In some ways, we’ve been doing the same thing all along. The technology and the process have been changing, but I don’t really think that’s the point. The idea and song are the main things.”

Much of Nanobots takes advantage of what is now a fully acclimated quintet that also includes guitarist Dan Miller, bassist Danny Weinkauf and drummer Marty Beller. “We’d been functioning as a two-piece for 10 years, and we really just sort of talked ourselves into it,” says Linnell of the bumpy transition, which began in 1992. “It’s still John and I making the decisions, but we lean heavily on the other guys for a lot of the musical resources. It’s a benevolent dictatorship.”

“When they first started working with a band, they were adapting it to what they already did,” says TMBG’s longtime friend and producer, Patrick Dillett. “But slowly, over the years, they’ve incorporated more of what’s standard for more traditional bands. It feels more organic.”

A three-time Grammy winner who’s worked with the likes of David Byrne, Tegan And Sara, Mary J. Blige and Mike Doughty, Dillett first ran into Linnell and Flansburgh when they were recordingFlood in New York. “He was an assistant at Skyline Recording Studios, which was a very hierarchical kind of place,” says Flansburgh. “It was dominated by Nile Rodgers when we were there.”

Not that there’s anything wrong with Nile Rodgers. “The first time I heard ‘Let’s Dance,’ I remember thinking, ‘This sounds like what cocaine must feel like,” says Flansburgh with a chuckle.

Looking for inspiration at Skyline, Flansburgh and Linnell found a co-conspirator in Dillett, and he’s been involved in the recording of just about every TMBG album since. One glaring exception is 1994’s Paul Fox-produced John Henry, which precipitated a creative malaise for Linnell and Flansburgh that carried through their final Elektra release, 1996’s Factory Showroom, and into the next decade.

“It has some great songs, but it was their first full album with a band,” says Dillett of John Henry. “It was tough for fans. Many of them simply decided it wasn’t for them, and that lingers for a lot of people.”

“We took a very hard right turn,” says Flansburgh. “We were intimidated making the transition to live musicians, and we wanted to hold on to control of what were doing. We actually demoed the entire album (with Dillett) and our live combo, and the difference between the demos and the finished album is scant. In fact, a lot of people prefer the demos.”

Though there were rumors to the contrary, Flansburgh says TMBG always played nice with Elektra. “People want to create drama when there often wasn’t much,” he says. “A lot of my best friends over the years have worked at record companies. If it wasn’t for Glenn Morrow at Bar/None, nobody would know who They Might Be Giants were.”

Morrow and, of course, MTV. “We started getting our videos played pretty early,” says Linnell. “Our stuff was being played alongside Whitesnake, and we were instantly perceived as something that was in opposition to the normal stuff. People thought of us as their personal discovery, and that worked in our favor.”

“To this day, I’m still kind of confused as to how the whole MTV thing happened,” says Flansburgh. “I think we were the happy solution to other issues at MTV. A lot of the spirit of our early videos is taken from the music sequences in A Hard Day’s Night. It’s a very lighthearted, breezy way of doing a video, and we reintroduced that idea to MTV and other video directors.”

As successful as it was, TMBG’s five-year run on MTV did everything but change the public’s perception of the pair. “It seems really petty now to complain about this, but we did feel like we were being caricatured in a way that was unfortunate and limited people’s interest in us,” says Linnell. “People thought it was a shtick—that we were some kind of nerd-themed project.”

For years, that infuriated Linnell. “But over time, I relaxed about it,” he says. “At one time, ‘nerd’ was a much more pejorative term. But something has changed in the culture now, and that’s no longer such a horrible thing to be.”

Exactly where does the grown-up TMBG end and the more kid-friendly version begin? The line is blurrier than you might think.

“When we started doing children’s music, we were fairly conscious of the idea that we wanted to apply the same spirit,” says Linnell. “As a friend of ours said, ‘I can see that you’re not lowering your standards just because you can get away with it.’ In other words, that somehow you can get away with shoveling filler into kids’ projects. The great thing about No! was that it was a fun and frivolous thing for us. We didn’t feel like it was a very high-stakes project, and so we wound up really enjoying ourselves making it, and being fairly reckless about what we thought was appropriate.”

TMBG’s subsequent crossover success led to a series of projects for Disney, one of which earned the duo a Grammy. “If your only music-culture navigation system is Rolling Stone orPitchfork, They Might Be Giants might not exist to you,” says Flansburgh. “The kids’ stuff got the word out in the mainstream press that we were still around.”

And there have been other revelations. “Doing the kids’ stuff made me realize how much code people tend to assume there is in what we’re doing,” says Flansburgh. “I don’t think we’ve ever really lived up to our reputation as culture smugglers. In a way, we’re just doing this thing that’s very direct to us, and I think people might actually be projecting the winking part.”

So, could it be that TMBG isn’t really that much of a UFO, after all?

“The truth of the matter is, we got pulled into popular music the same way everyone else did: the Beatles and all the shiny things in rock in the ’60s and ’70s,” says Flansburgh. “We weren’t coming from some ‘anti’ place.” Still, there’s something very heroic about being in a rock band, and we thought it was somehow bigger than us.”

Kids could care less about perceptions. They just know what they like—and their affection for TMBG has created another interesting dilemma.

“A lot of the indoor clubs we play aren’t suitable environments for children,” says Linnell. “We’ve had to insist that they’re 14-and-up or 18-and-up shows. It’s a complicated topic.”

And so, seeing as she won’t be joining me for a TMBG show anytime soon, my daughter had three questions of her own for Linnell, which I relayed to him.

The first: “How old are you?”

“I’m 53. How old are you, by the way?”

“I’m 46.”

“Wow, you’re a youngster.”

Second question: “Do you use synthesizers in your music?”

“The answer is a resounding yes,” says Linnell.

And the third: “What’s the favorite song you’ve ever written?”

“The gracious thing would be for me to pick a song by Flansburgh. Um, just tell her it’s the one I haven’t written yet.”

—Hobart Rowland

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

Okay they hit that shit clean

133 notes

·

View notes

Text

He's our homeboy

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

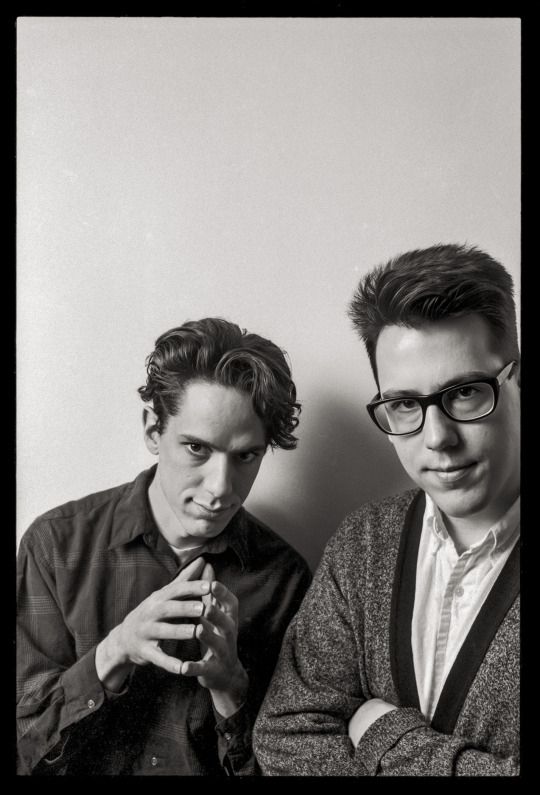

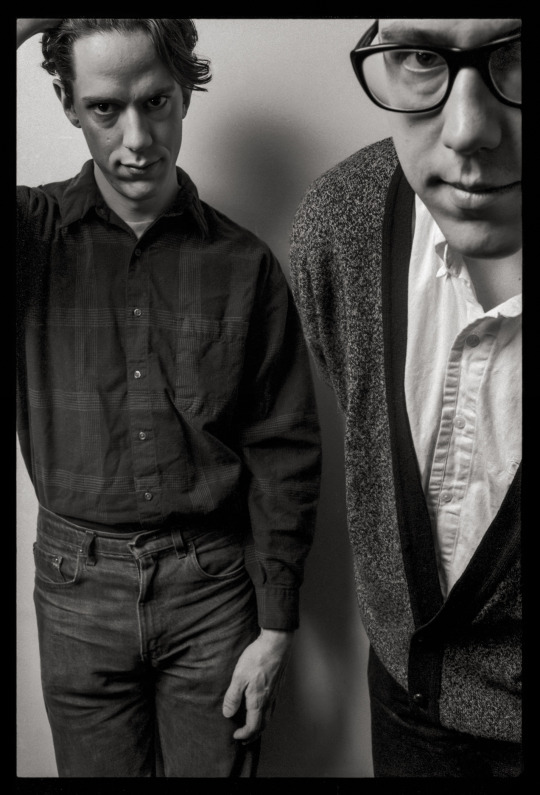

THEY MIGHT BE GIANTS Toronto 1990

John Flansburgh and John Linnell - known as "the Johns" or "the Two Johns" (a joke only '80s alt-rock nerds will still get) - met in high school in Massachusetts but formed They Might Be Giants in 1981, when they moved into the same apartment building in Brooklyn after attending different colleges. They built up a following playing clubs in the NYC area, a duo playing accordion, saxophone and guitar backed by a drum machine or taped backing tracks. They had just emerged from what we used to call the indie circuit and released their third album, Flood, on Elektra Records in 1990, when I was assigned to photograph them for the cover of NOW, the big alt-weekly in the city.

They Might Be Giants had proved to be deft hands at self-marketing during their years as an indie acts, putting on a theatrical stage show in NY clubs and running Dial-A-Song on an answering machine starting in 1985. Fans could call a number (718-387–6962) and hear demos or incomplete songs from Flansburgh and Linnell. More than a gimmick, it helped establish the band's identity as creative but unpretentious, produced a compilation album and was still in service until 2008 when they had to retire it and the number. (It was revived in 2015 as a toll-free number, a website and radio network.) The band have written themes for TV shows like Malcolm in the Middle, songs for musicals and won Grammys for their children's albums.

It was still early in my time at NOW magazine when I got the assignment to photograph They Might Be Giants for a cover story, which meant both colour slide and black and white. I have no memory at all of where these photos were taken - probably a hotel room downtown - but I know I brought my single Metz flash on a light stand shooting into an umbrella, and used my Nikon F3. NOW covers were shot to a rigorous formula at this time - the subject squeezed into at most two-thirds of a vertical frame with space at one side and the top for the logo and cover type. It was restrictive and tiresome, but we had just innovated slightly by convincing the paper to drop their unofficial (and baffling) ban on white backgrounds.

I had obviously found the white wall in whatever space where this shoot took place, and got the band to tuck themselves into my frame. Flansburgh and Linnell were more than cooperative - they seemed to sense what I needed to convey the quirky energy of the band, and provided me with more than enough material for the cover layout - a big deal since I still felt very much on probation at NOW at the time. This is the first time these photos have been published since the story ran almost 35 years ago.

268 notes

·

View notes

Text

Portrait of the Johns “written” with my ‘50s typewriter.

686 notes

·

View notes

Text

if you are a normal sized human being who overdrafts at the bank youd have to pay a fee or fine but if your a giant you'd pay a fo or fum

21K notes

·

View notes

Text

if you are a normal sized human being who overdrafts at the bank youd have to pay a fee or fine but if your a giant you'd pay a fo or fum

21K notes

·

View notes