Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Understanding Trump's appeal, without resort to misanthropy

I once had a boss who, on becoming the chair of an academic department, made a seemingly inexplicable appointment of a particularly nasty woman to be the department’s administrator. This ogress had been employed as a technician within the department for several years and had the credentials to function as an administrator, but she was not the only one qualified for the job, and the other intradepartmental contenders were all courteous and always maintained a professional demeanor. Most of the staff was puzzled that it was this particularly abrasive harridan who got the promotion.

The logic of this decision soon became apparent. The administrator came to function as a gatekeeper to the chairman’s office. She sat at a desk just outside his office door, which was always closed. She answered the chairman’s phone and scheduled all his appointments. Anyone wishing to meet with the chairman had to provide, and justify, the reason for the requested meeting. Such requests often resulted in verbal put-downs and even mockery from the administrator, which required dogged persistence to overcome.

The chairman, who appeared to all as a thoroughly nice person, once confided in me that he knew many of his staff and faculty members disapproved of his choice of administrator and didn’t understand why he had made it. He confessed that he had selected this woman specifically because her nasty temperament would make anyone think twice before attempting to get into his office to see him. He was not a particularly tough person, and he abhorred the idea that an open door to his office would allow constant visits from those who wanted to criticize decisions he had made or otherwise argue with him.

In short, he was looking at this woman instrumentally, in that her off-putting personality served a particular personal need for him, protection from having to constantly defend his decisions. (Even though many might argue that this is a fundamental part of the job of a department chair.). She was not promoted because she was especially talented or because having her in that position was likely to enhance the functioning of the department as a whole.

Philosophers, notably Immanuel Kant, have taught us that individual persons should be seen as ends in themselves, that they should not be used as instruments to achieve the personal ends of others.

I suggest that many of the people in Trump’s base, the MAGA crowd, see Trump instrumentally, the way my boss saw his administrator. They may not approve of his crassness, vulgarity, mendacity, narcissism, immorality, or all-around nastiness – in fact they may be repulsed by them – but this is not the point. His nastiness serves them, it protects them, like the administrator in front of the chairman’s door. It protects them from what they are convinced are threats to their own well-being, the foreigners who might compete for their jobs and the native elites who look down on them and devalue their work.

The people of Trump’s base have effectively sealed themselves off from the rest of the American population, in a societal equivalent of the department chair’s office, sequestered from the outside world. The office door is closed and guarded by a dragon, whom they revere and celebrate for the protection he gives them. They do not wish to emulate the dragon, only to enjoy the sense of safety he provides. Their mutual joy in his useful presence promotes interpersonal bonding among those within the office, just as the solid walls of the office cut the bonds they once had with the outside world.

The interpersonal bonding in MAGA crowds is readily apparent in the video clips of interviews done by Jordan Klepper of The Daily Show at Trump rallies. In spite of Klepper’s pointed questions and his mocking attitude, the individual Trumpers appear joyful and at peace with themselves.

Unfortunately, the sealed office mentality now seems to have rubbed off on the Democrats.

The “chairman” has been sequestered in his office for many months now, the loss of his ability to communicate with the common people kept secret from the public by his staff. When his disability was fully displayed at the recent debate with Trump, the response by the party’s leaders was a denial of the obvious fact. The party seems well on its way to being as much a personality cult as the Republicans: only Biden can win against Trump, i.e. save our democracy. To my mind, any political party that elevates loyalty to a single person above its principles and its effectiveness in winning elections, and rejects the preference of a majority of its members, can hardly claim to be serving the cause of democracy.

The Democrats have touted for years that they believe in science, unlike those who deny the reality of human-caused climate change or effectiveness of vaccines. Yet now, many Democrats reject the results of public opinion polls, produced by as rigorous, albeit inexact, a scientific discipline as meteorology or medicine. They simply say that polls predicting Biden losing to Trump are wrong, not to be believed.

Since there is no practical way to nominate a new Democratic presidential candidate other than by Biden’s voluntarily relinquishing the nomination and throwing his support to someone new, and since he shows no sign of willingness to do so in the face of divided party leadership, I expect that the re-election of Trump is a foregone conclusion. I’m basing this expectation not just on polls, but also on life experience. Most people I’ve talked to over the years do not have much interest in national politics or much commitment to any particular political ideology. They tend to vote for candidates on the basis of personal characteristics and physical appearance, conveyed to them in images by the media, often speaking of them in terms that would be more appropriate for friends or acquaintances – nice smile, warmth, good to have a beer with. Evaluations of this sort seem hopelessly superficial to politics junkies, but I think it accounts for far more of the votes cast in elections at the national level than those that are ideologically driven. A candidate with the image of a frail, bumbling old man is not going to do well in this setting.

0 notes

Text

Fleeing Lake George

Memoir

We viewed ourselves as super-parents, my wife Mary and I. We had both entered demanding professions after our years of schooling. We had defied our culture’s customs by postponing children till well past the prime of our youth, to an age when we were more comfortable financially and settled into our career paths. The new birth control pills had made it possible to juggle two careers with the rewards of child-rearing.

We seemed to have mastered this process quite well. We were later even than most of our yuppie peers in starting our family; my wife and I both changed career paths in our twenties and didn’t get settled into what felt like permanent tracks until the next decade. Mary had gone to law school after first trying a career in journalism. When would her career be sufficiently secure to allow children to appear on the scene? We picked the point at which she had acquired the seniority to prosecute felony trials on behalf of the District Attorney. That seemed an appropriately high rung on the career ladder.

But conception did not occur as soon as we expected. Our family development schedule was delayed. I was now close to forty and Mary two years younger. We worried that we had waited too long, that we had become too old. But, thanks to a medical infertility specialist, Mary eventually became pregnant and successfully bore our first child, a little boy we named Derek.

Our new lifestyle combined the nurture and care of our new child with our continued devotion to work. But we had ample resources, with a large home in the suburbs, and the two professional salaries. We hired a full-time nanny. By the time our little Derek had progressed from baby to toddler, we thought we had everything worked out in the way of work-life balance. Now to advance to the planning stage for child #2, and our idealized nuclear family would be complete.

It seemed inevitable that the process would be smoother the second time around. We now knew from experience the hoops that had to be jumped through. In her first pregnancy, Mary had managed to get on the patient list of Bronxville’s most sought-after obstetrician, Dr. Joshua Davies. It was now a given that Dr. Davies would attend her throughout this repeat pregnancy and deliver our second child. He was one of the rare local MDs who practiced without partners, so his patients developed a closer bond with him, more personal than would be possible if one were enrolled with an obstetrical group practice. His medical reputation was impeccable – solid credentials and the son of Bronxville’s star OB practitioner in previous decades – and he was a remarkably charismatic individual. He accompanied the routines of the prenatal examination with an apparently spontaneous spoken patter that touched upon the psychological and philosophical challenges of parenting, often with allegorical references to venturing on new pathways in the wilderness of one’s life, or something similar. I tried to get off work to accompany Mary to her checkups whenever I could; I used to joke that it was like going to a prenatal visit with Walt Whitman.

Mary and I had recently found that we would not be able to enroll our little Derek in the most prestigious of the pre-school programs in our locale, the program at Sarah Lawrence College. His name was put on a waiting list, but there were so many ahead of him, we were told it was unlikely any openings would be left when classes for his age group were to enter. We were determined to try this again with our new child, and get it right this time. We persuaded the school officials to enter the new baby’s name on the waiting list as early as possible, before he was even born, when Mary was in the third trimester of her pregnancy. We knew he was a boy from the amniocentesis and ultrasound results, and we committed to a name, Gavin Todd, which seemed to go well with the simple monosyllabic last name Smith.

Mary continued full-time work, planning not to go on maternity leave until the week before her due date. She was now well used to the way the baby inside her would kick up a storm when she got up to address a jury during a trial.

We planned to commemorate the transition from working pregnancy to home confinement with a weekend away for the three of us, a brief vacation in the country just before the due date. It would be some time before we would be able to travel again, after all. It was then nearing the end of summer, prime tourist season. We booked a cabin on the shore of Lake George, prudently, many weeks in advance.

***

The first sign that all was not right came two weeks before the due date. Mary went by herself to an afternoon appointment with Dr. Davies. His waiting room was uncharacteristically deserted. She asked the receptionist if he had been called away to perform a delivery, but no, he was there, and she was ushered immediately into his office.

He was unusually closed-mouth in the conversation that followed. “Mrs. Smith, I’m afraid I can’t do your delivery at Lawrence Hospital, as we had planned. But I can offer you the option of doing it at Women’s Hospital in the City, where I also have privileges.”

“Why is that? Why not Lawrence?”

“Well, they’ve suspended my privileges at the moment. It’s not a big deal, just got behind in some paperwork. But I’m not going to be able to straighten it out before you deliver, it’s coming up too fast.”

She told him she would think it over and get back to him.

The next step was to investigate more thoroughly what had happened with Dr. Davies. This was easy for Mary to do, it turned out, because of her work at the District Attorney’s office. Dr. Davies had been stopped late at night by the local police because his driving appeared erratic. Illicit drugs were found in his car and he was determined to be under their influence. This was reported to medical authorities, and this was the real reason for his suspension at the hospital.

There was no real choice, of course, but to switch doctors. It was not easy because the local OBs were struggling, having to absorb all the patients from Dr. Davies’s previously thriving practice. We eventually found a doctor who could do deliveries at Lawrence but whose office was in Mount Vernon. He was a nice enough fellow, but all business in his manner with patients. He basically remained a stranger to us, since we were to see him over the course of only the few weeks that remained before the expected delivery date.

Now that our original plans had been disrupted, our rosy self-confidence faded. We still had the joyous prospect of a new baby on the horizon, and we had just been spared the enormous risk of placing Mary’s and the baby’s care, at a crucial moment, in the hands of a doctor who was likely impaired. But it was hard to see this as a cause for celebration. We had developed so much trust in Dr. Davies, had found him a source of inspiration, and now we felt betrayed by him.

***

We kept to the timeline of our original plan. It was warm and sunny on the Friday afternoon that we drove to the cabin on Lake George. We checked into our room, unpacked, and ate supper at a restaurant across the road from the cabin. The sun was going down as we began the walk back. There were some young people gathered around a bonfire in a parking lot, playing music and dancing. Derek joined in the dancing. (Is there ever a sight more joyful than a toddler dancing, spontaneously and unselfconsciously?)

We retired to our room, and full darkness descended. It was more like a fog, a palpable darkness, not just mere sundown. I suddenly felt a sense of despair and saw the feeling mirrored in Mary’s eyes. It was hard to move, like being weighed down with a burden. Only Derek seemed unaffected by the sudden shift in the mood.

With a minimum of discussion, Mary and I agreed it was imperative for us to return home immediately. Such quick resolve was unusual for us, we usually dickered about such things. We checked out of our unused cabin and made the drive home without stopping. The southbound Throughway was very dark and deserted, except for the occasional speeding tractor-trailer, and I drove as if in a trance. It did not occur to me to ask myself why I felt compelled to do this, why I felt we were compelled to flee. It was after three in the morning when we arrived home.

***

I took the next Monday off work to look after Derek, and Mary kept a morning appointment with the new doctor.

My somber mood had continued through the end of the weekend, which may explain why I lapsed in my supervision of Derek that morning. He was able to climb unwatched to the top of the counter in our hall bathroom, perhaps attracted by his image in the mirror. He then discovered one of Mary’s tubes of lipstick. He applied the lipstick to his own lips, then, apparently fascinated with the process, continued to apply it to other parts of his face, then other parts of his body, then the mirror and other fixtures in the bathroom. This was the state of the bathroom when I finally discovered what had happened. It was a scene of faux carnage, splotches of brilliant red everywhere, like spattered blood. I could say very little, I just felt enormously weary. I turned on the water for the bathtub, slowly beginning the cleanup procedure, of both the innocent little boy and the room.

I was in the midst of the cleanup when Mary returned home from the doctor, bearing sad news. Our baby Gavin had died within her uterus. The doctor had suspected this on the examination and confirmed it with an ultrasound. Oddly, this revelation did not surprise me. I had been feeling, deep inside, that something terrible had happened that weekend; I was certain of this and what it was finally had been made explicit.

I’ve since learned that a pregnant woman can sense the death of the child she is carrying on a subconscious level. She becomes accustomed to the subtle sensation of the fetal heartbeat throughout the pregnancy and then perceives something has gone wrong when it suddenly ceases, even though she can’t specify the source of her anxiety. I believe this is what happened to Mary in the cabin at Lake George, and that I must have picked up on her anxiety.

The death of a baby not yet born has a sorrowful post script. Experts recommend simply awaiting the onset of natural labor as the safest course, which can take days or weeks. In the meantime, as the grieving mother goes about her usual activities, she will interact with people who assume she is in the late stages of a normal pregnancy. What Mary did, I suppose, is the natural thing in this situation; people who knew her were told the sad news. For people who were strangers, whom she did not expect to see again, she pretended everything was going well and accepted their congratulations.

After the baby’s delivery, we authorized the pathologists at Lawrence Hospital to perform an autopsy on his body, a procedure that can help to clarify whether there were any conditions associated with the death that might affect any future pregnancies. I am a pathologist myself, and the pathologist who performed Gavin’s autopsy was a colleague. She and I discussed her findings at some length afterward, mostly in technical language, although I sensed in her tone of voice that she wanted to convey to me that she shared in my sorrow. There were no suggestions of risks that would carry into the future, and when she concluded her summary by saying he had been a beautiful baby, it seemed a truly heartfelt reflection of her own compassion. As is often true in stillbirth, the autopsy provided no clear explanation of why the baby died.

***

Many years have passed since this occurrence, and they saw the successful addition of a second child to our family. When I reflect on the death of this middle child, as on other sad events in my past, I can see that it brought with it some valuable lessons. It certainly set me straight with regard to the amount of control I can expect to have over the future course of my life. I retreated from the hubris of imagining myself a super-parent, and I think I was a better Dad in later years because of it.

Viewed in retrospect, the two happenings that were virtually simultaneous, the exposure and disgrace of our trusted and beloved Dr. Davies, formerly the rock and cornerstone for our fledgling family, and the subsequent death of our baby, seem inextricably linked as chapters in the same sad story, even if there was no causal connection between the two. And, as irrational as it seems, I continue to feel overpowering sadness every time I have occasion to go to Lawrence Hospital, the setting of most of the events of the sad story, even though its management and staff performed admirably on our behalf.

I’m now fairly far along in life, not far from its end, and I’m comforted by my primary care doctor’s assurance that when my final illness comes, she will not be admitting me to Lawrence. I haven’t explained my preference to her, but it’s basically because the ambience of that hospital is too weighted with sad memories for me already.

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Backyard Trellis

Memoir

It was the summer of my fourth year. My mother, younger sister and I had recently moved from Louisville to Chicago and we were staying with my maternal grandmother in her walk-up apartment on the south side of the city. It was not far from Midway Airport. I used to see the airport searchlights sweeping the night sky from the window by my bed as I drifted off to sleep. My parents had separated during the war and were eventually to divorce, and my father was at that time living in another part of the country.

My mother took me with her to visit a college friend of hers, Gert Silverman, shortly after we moved in with my grandmother. Gert and her husband Nate had bought a house in the south Chicago suburbs. This was the first of many times I was taken to the Silvermans’ over the course of my childhood. Even after my mother moved us to the West, the occasional trip back to Chicago always included a visit to see Gert and Nate. I used to look forward to these visits. Gert and Nate loved being visited by children, and they were among the few grown-ups who wanted my sister and me to call them by their first names. Their house had an expansive back lawn that bordered on a commuter rail line. As an older child, I would interrupt my running about the yard to wave to the engineers of the many passing trains and they would usually wave back.

For this, the first of my visits to the Silvermans, my mother felt it necessary to coach me in advance regarding my behavior. She told me that Gert and Nate had a son named Bobby who was the same age as I. Of course, it was expected that Bobby and I would play together while we were there, but I had to understand something important about Bobby. He was a boy and he was my age but he was very different from me. He could not run or climb on things, which my mother knew were my favorite play activities. Bobby and I could only “play quietly” while we were together.

When we arrived, I was immediately intimidated by Bobby. My mother had told me he was quite different from me, but I had not imagined his appearance would be so strange. He was similar in size and shape to me, but his skin was a bizarre mottled mixture of white and blue that was unlike that of any person I had ever seen.

I dutifully followed my mother, Gert, and Bobby to the back yard and sat down in the shady area Gert pointed out to me. She had Bobby sit a few feet away. Then both mothers retreated indoors, to the living room.

Bobby and I sat together silently for a while. I surveyed the yard, which at first appeared totally lacking in play equipment. Then I spied something at the perimeter that interested me greatly. I initially took it to be a set of climbing bars, a “Jungle Gym” that was a familiar feature in play parks near my home. When I got near it, I realized it was something else, too flimsy to have been constructed for children’s play. It was not securely anchored to the ground nor to the fence against which it rested. It was, in fact, a trellis, although there were no plants growing on it. Nonetheless, it invited climbing, and I could not resist.

The trellis flexed under my weight, but it stayed upright as I neared the top. Then I felt it move below me and I looked down. To my amazement, there was Bobby, who was following me, imitating my movements and climbing the trellis, and he was already past the first rungs. And he had, for the first time that afternoon, a broad smile on his face!

Bobby’s smile warmed my heart. The distance between us had suddenly vanished. And I felt I had just experienced an epiphany. Bobby and I really weren’t that different after all. My mother had been flat-out wrong when she told me that Bobby couldn’t climb. Of course he could climb, I had just seen him do it with my own eyes! So I imagined that I had just made an important discovery, uncovered an ability Bobby had that Gert and my mother hadn’t known about, and that they would thank me for finding it.

My mother, who must have been observing the back yard through a window, came storming out of the back door of the house, shouting my name, and scolding me, “Didn’t I tell you that Bobby couldn’t climb, and you led him to do it anyway!”

We left shortly afterward, amid my mother’s profuse apologies for my behavior, with my own mind in a state of confusion. I don’t know how long it took me to understand that when my mother had said Bobby can’t climb, she had meant he was not permitted to climb, that it might overly burden his poor little heart, not that he lacked the ability to do so.

I was stung by the ferocity of the scolding I had just received, by what seemed to me the injustice of being chastened for doing a seeming good deed, initiating a bond of friendship with another child.

I never saw Bobby again. This was a time before there were heart bypass machines, before cardiac surgery had developed ways to correct the effects of cyanotic congenital heart disease, and there was no hope back then for his survival. Gert and Nate had no more children. When we visited them in later years, their many years of childlessness after Bobby had died, we never spoke of him.

Now, in the autumn of my life, having experienced parenthood myself, and the loss of various loved ones over the years, I can only dimly imagine what it would be like to give birth to a child, and to nurture that child through infancy, knowing all the time that that child’s death is imminent and inevitable. Yet that’s what Gert and Nate were going through back then.

It occurs to me now, that the adults in the story – Gert, Nate, and my mother – were scarcely beyond childhood themselves when these events unfolded. Specifically, they were in their late twenties, much younger than my own children are now, possessed of the youthful energy required for the rigors of toddler care, but barely equipped to deal with the profundities of sorrow, suffering and death that normally are a part of later life.

I can’t help but wonder if my unknowing presence on that visit, rowdy and animated as I was and in stark contrast to Bobby’s frailty, made Gert’s sorrow more acute.

On another occasion, years later, I overheard my mother relate a conversation she had had with Gert when she visited her in the maternity ward shortly after Bobby was born and his terrible anomaly had become apparent. Gert asked my mother if she thought Bobby’s affliction could have been a punishment from God for her having married and conceived a child with a man who was a Jew.

The memory of my afternoon with Bobby never leaves me before I ask myself whether my enticing Bobby to climb the trellis caused him significant injury. Did my burst of infectious, naïve rambunctiousness lead him to overtax his frail body and, as a result, shave hours or days from the short lifetime that had been allotted to him? Even with the benefit of a medical education, I find this impossible to answer.

If there is ever a time or place where I am held to account for this particular impulsive act, I hope that it will be reckoned that the same costly event also brought Bobby a moment of joy, a moment revealed by the broad smile he showed me as he was climbing.

0 notes

Text

A Sermon

Isaiah 61:10-62:3

I will greatly rejoice in the Lord, my whole being shall exult in my God;

for he has clothed me with the garments of salvation, he has covered me with the robe of righteousness,

as a bridegroom decks himself with a garland, and as a bride adorns herself with her jewels.

For as the earth brings forth its shoots, and as a garden causes what is sown in it to spring up,

so the Lord God will cause righteousness and praise to spring up before all the nations.

For Zion's sake I will not keep silent, and for Jerusalem's sake I will not rest,

until her vindication shines out like the dawn, and her salvation like a burning torch.

The nations shall see your vindication, and all the kings your glory;

and you shall be called by a new name that the mouth of the Lord will give.

You shall be a crown of beauty in the hand of the Lord, and a royal diadem in the hand of your God.

John 1:1-18

In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. He was in the beginning with God. All things came into being through him, and without him not one thing came into being. What has come into being in him was life, and the life was the light of all people. The light shines in the darkness, and the darkness did not overcome it.

There was a man sent from God, whose name was John. He came as a witness to testify to the light, so that all might believe through him. He himself was not the light, but he came to testify to the light. The true light, which enlightens everyone, was coming into the world.

He was in the world, and the world came into being through him; yet the world did not know him. He came to what was his own, and his own people did not accept him. But to all who received him, who believed in his name, he gave power to become children of God, who were born, not of blood or of the will of the flesh or of the will of man, but of God.

And the Word became flesh and lived among us, and we have seen his glory, the glory as of a father's only son, full of grace and truth. (John testified to him and cried out, "This was he of whom I said, 'He who comes after me ranks ahead of me because he was before me.'") From his fullness we have all received, grace upon grace. The law indeed was given through Moses; grace and truth came through Jesus Christ. No one has ever seen God. It is God the only Son, who is close to the Father's heart, who has made him known.

Beginnings

First Reformed Church of Hastings-on-Hudson, NY, December 31, 2023

We are so blessed by the Lectionary this morning, which has given us the prologue of John’s gospel for our meditation. This beautiful passage is one of the most familiar in the entire Bible. I suspect it has a special place in each of our hearts.

Before we begin to consider the meaning of this text, it may be worth asking why we have come to love it so much, to ask ourselves what is the source of its beauty.

First of all, it is a poem. It’s a creation in language that engages our emotions directly, as well as communicates with the thinking, reasoning parts of our brain.

It may not strike you as a poem immediately, since it seems to lack meter and rhyme. It looks like prose on the printed page; most of our Bibles don’t print it as lines of verse. We need to think a little more about the nature of the poetry we find in the scriptures to understand it in this way. Although we read John’s prologue in English translation, and although it was originally transcribed in Greek, it’s structured as if it were a poem in Hebrew. English poetry is based on the vocalized sounds of words, the patterns created by regular repetitions of words with similarly accented syllables, and with rhyming created by parallel vowels. We experience it similarly to the way we experience music. Hebrew poetry is different; it is not based on pronounced rhythm and rhyme. Its prime feature is thought and word parallelism.

Consider the beginning two couplets of the first of today’s readings, the passage from Isaiah 61:

Line 1: I will greatly rejoice in the Lord, Line 2: my whole being shall exult in my God;

Line 1: for he has clothed me with the garments of salvation, Line 2: he has covered me with the robe of righteousness.

And so forth. This is an example of “synonymous parallelism”: two lines convey the same meaning but use different words. The first line states an idea and the second line rephrases the same idea in different words and imagery. Repetition of the same idea serves to emphasize, amplify, or clarify the meaning of the idea. The rhythm that is the essence of poetry is found in the regular repletion with which images are called up in our minds, rather than the repetition of sounds falling on our ears.

The prologue of John uses a somewhat different Hebrew poetic form, which scholars call “synthetic” or “staircase parallelism.” In this case, the second line of a couplet, rather than restating the first, builds upon it, expands it, and completes it. When the ideas are lined up in the format of a poem, successive lines extend progressively to the right on the printed page, giving the visual impression of a staircase.

and the Word was with God,

and the Word was God.

He was in the beginning with God.

and without him not one thing came into being.

What has come into being in him was life, and the life was the light of all people.

The light shines in the darkness, and the darkness did not overcome it.

The end result is similar; the ideas expressed are emphasized and their meaning is sharpened in our minds. They come thereby to live in our memory.

I’m not sure this kind of discussion will appeal to everyone. Many people who enjoy listening to classical music have no interest in learning about things like the elements of sonata form or the definition of a fugue. They will simply say, “I know I like to listen to this, it affects me emotionally, but I don’t have to know anything about all that terminology to appreciate it.” And I guess they’re right. They don’t need those academic definitions—but I would suggest that the underlying musical forms structure their listening experience, whether they are conscious of it or not. And I believe it is similar with Biblical poetry. It engages us on more than one level of perception, it engages us in more than one dimension, even if we haven’t explicitly acknowledged that we are reading poetry. It makes words we are hearing more special, and their meaning more important to us.

Incidentally, I’ve read that some Bible scholars have raised the conjecture that the prologue to John’s gospel may have been composed separately from, and earlier than, the rest of the gospel’s text, since it is the only part of the text that uses the staircase parallelism type of construction. Some have speculated that it may have been sung as a hymn in the early Christian communities in which John’s gospel originated.

Can you imagine what that hymn would have sounded like? To what sort of tune or chant it would have been set?

So now let’s get to the question of what that meaning is for us, why the content of John’s prologue tells us something important for us to know.

I think there are two points we could make here. One is to consider what it tells us about the nature of Jesus, about the special and unique sort of being that was—and is—his being. The Jesus we encounter in John is different from the Jesus of the other gospels, Matthew, Mark, and Luke, the “synoptic” gospels. For one thing, only in John do we learn that Jesus, identified as the Word, had existed from the beginning of creation. Although other sections of John’s gospel also indicate his existence with the Father prior to his incarnation, this aspect of Jesus’s nature is perhaps most clearly and emphatically declared up front, here in the prologue. In this sense, John 1 is unique among biblical texts, unique in its theology and Christology.

The second point is that John’s prologue tells something important about our world, its fundamental nature and how it came into being. In this, it is not unique among Biblical texts. It is, in fact, as our friend and neighbor, Rev. Aquavella sometimes reminds us, one of as many as five places in the Bible where we are told how the world as we know it came into existence.

Of course, the very first lines of the Bible begin the story of God’s creation; it’s actually told here twice, first in Genesis 1 and then retold somewhat differently in chapter 2. Then there is a third telling of the creation story in the book of Job, a story some find more dramatic than those in Genesis, since it’s told by God himself—a first-person account of creation—when he begins his stirring declaration to Job from out of the whirlwind, “Where were you when I laid the foundation of the earth?”

The creation narratives in Genesis and Job emphasize the power and majesty of God; they leave us awed and humbled. And this seems to be an appropriate way for us to regard the author of this universe of ours that we know to be so vast and so ancient, and who must therefore exist on a comparable scale.

But is it the only way? The only way to regard our creator?

Before we contrast today’s reading from John, let’s look at chapter 8 of Proverbs. This is another account of the beginning of the world, the onset of time and of human existence. The story centers on a sacred being who is Wisdom personified, present and providing guidance to God throughout the work of earth’s construction. Wisdom speaks to us in the first person:

The Lord created me at the beginning of his work the first of his acts of long ago. Ages ago I was set up, at the first, before the beginning of the earth. When there were no depths I was brought forth, when there were no springs abounding with water. Before the mountains had been shaped, before the hills, I was brought forth, when he had not yet made earth and fields or the world’s first bits of soil. When he established the heavens, I was there; when he drew a circle on the face of the deep, when he made firm the skies above, when he established the fountains of the deep, when he assigned to the sea its limit, so that the waters might not transgress his command, when he marked out the foundations of the earth,

then I was beside him, like a master worker, and I was daily his delight, playing before him always, playing in his inhabited world and delighting in the human race.

On reading this passage from Proverbs, it is almost impossible not to be reminded of those opening lines of John, particularly because of the parallel between the characters Wisdom and the Word. The expression Word has been translated from the Greek logos, from which we get the English word logic, and which, in the original, carried the additional meanings of logic and reason. It’s not surprising to learn than many Christian scholars over the years have come to regard the character of Wisdom in Proverbs as a prefiguration of Christ.

The two stories of the beginning told in Proverbs and John strike us rather differently than those in Genesis and Job. They do not provoke awe and humility, so much as comfort with what the world holds out for us. By making reason central to the world of human existence, they seem to say that the world is a coherent place, that it runs on rules, and that we humans have some ability, our ability to reason and to understand principles of law and justice, to make sense of it and make our way within it.

This is not to deny that the world is in fact vast, unimaginably old, and ultimately beyond human comprehension. But at the same time it is also accessible to us. These two truths, which come to us in these scriptures, are opposite sides of the same coin.

The five creation stories contained within our Bible are, of course, not the only ones that various peoples have come up with over the course of human history. Creation myths have arisen within many societies around the globe. But they’re not universal. The ancient Athenians, for example, Aristotle among them, believed the world had never had a beginning, that it had existed forever. And it would continue forever into the future.

Scientists now can tell us much about the beginning of everything, in the language and concepts of astrophysics and the “hot, inflationary, big bang.” Eternal unchanging existence is not compatible with the data that has now accrued. I’m not sure whether or not we Christians ought to be patting ourselves on the back for having received scientific corroboration, for being part of a tradition that has believed all along that there was a beginning. I do believe that the eternal existence of the world does not make for a very good story. It does not resonate with what we, as individuals, come to learn about life. All that we ever know, that we ever experience, that we ever love, comes to end, including each of us. If all this took place on an infinite, timeless stage, it would seem to me to rob life of much of its meaning.

I hope that we have been cheered by reading today’s words of praise for human knowledge and reason that have been passed down to us within the scriptures. We perhaps need to acknowledge, each of us, the important role that reasoned contemplation can play in our spiritual lives. We also can’t deny that critical reasoning has played an important role in the historical development of our faith. It’s unfortunate that we are currently exposed to so many individuals in our culture whose approach to their religion and the Bible could best be described as “naïve literalism.” May all of us come, instead, to a place where we meet God with full use of the wisdom and understanding he has given us.

Amen.

0 notes

Text

The Return from Tiburon

A Memoir

I. Familial Racism

Our small town in Western Colorado had not a single African-American resident and yet most of our family discussions over the dinner table were infused with racist sentiments, generally—but not exclusively—directed against African-Americans, who were invariably referred to with the infamous and execrable “N” word.

The setting here is the decade of the 1950’s, the Eisenhower years, when I was a child. The national news of the day generally included stories about the civil rights movement, and it was my mother’s and stepfather’s opinions about the leaders and activists in the movement that usually started off the discussions. A common theme was that these people were loudly and raucously demanding various rights and privileges without being willing to accept the responsibilities that came with them.

My mother would often explain to me and my younger sister that the reason she and my stepfather so often dwelt on this topic was largely for our benefit. We were being protected now by living in a small town filled with people of our own kind, but we would undoubtedly, at some time in the future, go into the outside world and come into contact with all sorts of people. We should know that these people with dark skin who lived mostly in cities were dangerous to be around and we should avoid engaging with them in any way. They were not only less intelligent, less morally responsible, and less diligent than us, but they were also inherently violent and hated people with white skin.

My sister and I, like all good children, believed that our parents had our best interests at heart and that we should follow their instructions should we ever come across a Black person. In our young minds, we put such persons in the same category as the mysterious malevolent stranger who would offer us a ride in his car that we were also so frequently warned about. When we thought of these various kinds of grown-up people that were dangerous to us, we felt a certain amount of fear, but we never experienced the scorn for Black people that was so evident in the way our parents spoke of them. It was never clear at the time why our parents had such hatred in their hearts for Black people.

Thinking back on those days now, as an adult, I understand better. My stepfather came from a family of poor Southern whites, a disadvantaged group whose members frequently experience feelings of low self-worth and compensate by telling themselves that they are at least of higher intrinsic value than a Black person. This belief dates from the ante bellum South when enslaved African-Americans were believed to be less than fully human.

My mother’s story is a little more complicated. She grew up on the south side of Chicago. Her father, an immigrant from Bavaria, had risen from poverty to become the owner and sole operator of a dry goods store on South Cottage Grove Avenue, farther north and closer to Chicago’s downtown than the family’s residence. Her father’s store survived the first years of the Great Depression but went bankrupt when the neighborhoods surrounding the store “turned Black,” as the saying went, in the later 1930’s. “Turning Black” occurred when a single Black family would buy a house on a residential block, and their white neighbors, panicked at the thought that their property values were going to drop precipitously, would sell their houses as rapidly as possible, hoping to minimize their losses. Within months the entire block would have been sold to Black families, many of them recent arrivals from Southern states. Unscrupulous real estate agents made fortunes from commissions earned by turning neighborhoods this way. Because the new families were strangers to each other, the old sense of cohesion and shared history in the neighborhoods would be lost, and they became susceptible to crime.

My grandfather, who was then only in his late forties, died a few years after losing the store. His health was poor as a result of having contracted the more virulent form of malaria during the years he had spent in Louisiana before moving to Chicago.

My mother may have absorbed some Southern attitudes from her father, including the generic one that affected my stepfather. More likely, I believe, she might have blamed the failure of her father’s business, and even his death, on the societal catastrophe whose most visible element was the influx of Black people into formerly stable white neighborhoods. Ultimately she projected this blame onto Black people themselves.

II. Redemption

In the late 1950’s our family took annual week-long vacations to cities. One year it was Denver, the next Salt Lake City, and the last was San Francisco. My parents felt it would be good for my sister and me to have a chance to see all that cities had to offer in the way of culture, history, international shops and restaurants, and the like, aspects of civilized life we never encountered in our provincial environment. Cities were potentially dangerous, of course, but this limited amount of exposure, under constant parental supervision, seemed safe enough.

We knew to keep our distance from people of other races who might be near us on the sidewalks or in the shops and museums when we roamed the cities.

We always traveled to our destination city by car. Once ensconced in our hotel, my parents left our car in the hotel garage for the rest of the week, because they didn’t like negotiating city traffic or dealing with problems of parking in congested areas. We usually did a downtown tour by bus on the first day of our itinerary and then Mama would plan day trips on our own for the rest of the week, using whatever types of public transportation the city had. My stepfather would often beg off on these day trips to catch up on sleep in the hotel room. He did almost all the driving on the treks from our home town; he would drive all night while the rest of us slept in the car. (The night driving minimized traffic snarls and avoided the daytime heat. There were no interstates back then, and our trips were always in the summer in an era when cars with air-conditioning were only for the wealthy.)

We had become expert explorers of cities by the time we made the trip to San Francisco. Mama learned from the hotel’s desk clerk at check-in that the municipal buses there had recently adopted a fare policy that required you to have the 25-cent fare in exact change when you boarded a bus, so she immediately went to a nearby bank to convert some large bills to rolls of quarters, which she carried around in her purse for the duration of our stay. We crammed numerous excursions into the limited numbers of days we had at our disposal in San Francisco; we did the cable car ride to Fisherman’s Wharf, of course, and bus rides to the Presidio and Embarcadero, and we combined bus trips and ferry voyages to Sausalito, Angel Island, and Tiburon, across San Francisco Bay.

An episode on our return trip from Tiburon, just Mama and my sister and me, remains imprinted in my memory to this day.

We disembarked the Tiburon ferry, which had carried few passengers that trip, and walked to the bus stop in front of the Ferry Terminal. This was a terminus for the bus line, and the schedules the bus drivers observed required them to wait ten minutes at the stop to collect all the arriving passengers from the most recent ferry. We were the first ones on the bus. Mama deposited the requisite quarters for our rides in the fare box next to the driver’s seat as we got on, and she asked the driver if he could alert us when we were approaching the street near our hotel. The driver was a uniformed black man with a gruff manner, a bit scary to us children, but he agreed to alert us, and we took the inward-facing bench seat at the front of the bus opposite the driver so that we would be sure to hear him when he called out our stop.

A few minutes passed, and then the next passenger boarded, apparently the only remaining ferry rider from Tiburon who was taking this particular bus. It had taken her much longer to make the walk to the bus stop than it had taken us. She was a sad-looking Black lady, stooped in her posture, carrying a tattered shopping bag. In my visual recollection of her, she’s a woman who has obviously had a hard life, possibly a domestic worker employed by wealthy suburbanites and returning from a stint of live-in work to her own home, a cold-water flat in the inner city.

The Black lady held out a dollar bill to the driver.

He glared back at her with a look of undisguised contempt. “What’s this? Lady, you gotta know you can’t get change on the bus anymore. There’s a new rule. You gotta have exact change to get on the bus. I’m not gonna make change for you. Those days are over. You gotta know that. It’s been in the papers and all. On the radio. Everybody knows that.”

He paused. She continued to extend her hand with the bill, but it was now shaking.

“Look here, Lady. I’m onto you. I know who you are. You and your kind. You show me you have money and you have every intention of paying your fare, but you just happen to have forgot—it just slipped your mind—that you have to have the money in exact change now. Such a minor detail! And you expect me to be gracious about it, and say of course, such a trivial thing, forget about it, take a free ride now and pay the next time, that’s OK. And then you do same thing the next time, to the next driver, and you get free rides all over the city.”

He paused again, then motioned with his thumb for her to proceed past the fare box to the seating area. She was shaking all over now. “Lady, you win. I gotta start my route, and I don’t have time to deal with this. You get a free ride again this time. But you should know that I see through you. You’re a cheater and a con artist, and it’s people like you that are costing the city and the bus system a lot of money.” He slammed the door shut and drove the bus out into the street to begin the route.

I have sometimes, these many years later, thought about this terrible confrontation on the bus and asked myself why the three of us had sat watching it so passively. Mama could easily have defused the situation by standing up and paying the woman’s fare herself; she had a big supply of quarters in her purse and we could certainly have afforded it. I think the answer is that we were totally stunned by this ferocious verbal attack on the part of the bus driver. People living in small towns like ours never displayed such strong emotions in public. It just wasn’t done.

The lady slowly walked back to the passenger section of the bus as it began to move and then collapsed into the bench seat opposite us, behind and out of sight of the driver. She hung her head and began to cry, at first silently and then audibly. Her sorrow was palpable.

And then something truly amazing happened. My sister and I were astounded to see Mama get up from where she was sitting next to us, walk across the aisle of the bus, and sit down next to the weeping woman.

Mama leaned over toward her and said, very tenderly, “Oh my dear. My dear. Men can be so cruel, can’t they?”

The woman raised her head and turned to Mama. “I’m not a cheater. I didn’t know I had to have change to ride the bus. I haven’t been back to the city in a while. I just didn’t know. I didn’t mean any harm. I didn’t know about this exact change rule.”

“Of course you’re not. Of course you didn’t.”

More words were exchanged, but too softly for my sister and me to hear.

After a few more minutes, the woman seemed more composed, the tears abated, and my mother returned across the aisle to sit with us. We sat in silence the rest of the ride and the driver notified us appropriately when we reached the stop for our hotel.

That night, in the hotel room, my sister asked Mama about the woman on the bus. “Mama, why did you talk to that lady on the bus? I thought you didn’t like Black people. I thought you said they were dangerous and that we shouldn’t ever talk to them.”

Mama was uncharacteristically silent for a moment or two and a look of guilt spread across her face, as if she had been exposed betraying her own principles. Then, as the memory of the recent event began to replay in her mind, her expression became one of anger. “No one should ever be talked to that way. No one. Ever.”

That was it, she had no more to say about it.

The lesson my sister and I learned that one day in San Francisco was more meaningful than anything we had gotten from all the lectures over the dinner table at home in Colorado.

0 notes

Text

Discovering My Father

A Memoir

My childhood memories contain no trace of my father.

He was present in my childhood only in the very earliest years, infancy years, before memories can form and stay with you. He was away, in the Navy serving as a ship’s doctor in the Pacific during World War II while I was still in diapers. He was never to return to us. My mother learned of incidents of infidelity during his travels and banished him from the household forever.

Mama’s banishment decree created a vast separation between him and what remained of our nuclear family. He was never to be spoken of at home, nor his existence acknowledged. Mama remarried, after the divorce, a man 10 years younger than herself, and she arranged for my younger sister and me to be legally adopted by our new stepfather. We took on his surname, and the order was given that we must now call him, and think of his as, our father.

This radical restructuring of our family troubled me in the ensuing years. My true father had had to sign off on the adoption papers, in return for which he was relieved of any child support obligations. I found myself wishing he had refused, had angrily denounced this slashing of all bonds between us, we who were his flesh and blood! Could I ever forgive him for that?

My stepfather came from the rural South; unlike my mother, he had received no education beyond high school; and he had always worked in blue-collar jobs. He had been raised in a fundamentalist Christian family, and he saw the world in stark, black-and-white tones, full of wickedness and insolence, demanding draconian punishments. He professed love for me at times, but even at my young age I could sense this was perfunctory, not genuine. I remember more vividly how strongly he felt that I, a coddled Mama’s boy, was sorely in need of punishment, which he proceeded to administer liberally. One of the cruelest punishments I received, a prolonged beating with a rubber hose, was for forgetting one of my assigned daily household chores. I think he had interpreted my lapse in duties as an act of defiance of his commands; I look back on it, to this day, as a typical oversight committed by the absent-minded, day-dreamy sort of person that I have always been.

I was puzzled, as I grew older, by the obvious strength of the marriage bond between my mother and stepfather, and by the way she appeared to defer to him in so many family matters. She was clearly more intelligent and more learned than he; she had a BA degree from the University of Chicago, after all, the sort of distinction which was quite a rarity among the residents of the small town in Western Colorado where we lived. As the years went on, my stepfather proved a failure as a family breadwinner, and Mama then became our sole financial support. I now wonder if Mama wasn’t doing a little bit of acting back then, taking on the role of subservient homemaker to make us appear more like one of the conventional nuclear families we were seeing on television. I also wonder if she over-valued her marital relationship because, with the bitter memory of her first marriage, she knew my stepfather was not the sort of man who would ever betray her.

I am often troubled reflecting on Mama’s passive acceptance of the abuse I was receiving from my stepfather. Did she really believe that the beatings, as well as his continual teasing and belittling of me, were in my best interest? She had absorbed certain cultural attitudes of the American South from her own father, a Bavarian immigrant who had spent his first years in his adopted country there, learning American norms and customs in Slaughter, Louisiana. Perhaps she really believed that boys needed to be physically beaten and verbally assaulted, to toughen them up, to grow up properly. In any case, I never understood why this otherwise active, independent, outspoken woman, who seemed to have such a deep understanding of the world, never stood up for me. Such thoughts created a barrier that prevented me from ever trying, as an adult, to develop and nurture the loving, open relationship with my mother that I would otherwise have wished for.

Throughout my teen years, I yearned for escape from the toxic environment I had at home. Coming into young manhood, I was accepted at a prestigious college in the East, and I saw this as a kind of salvation, since I now had a practical excuse for minimizing my visits back to Colorado. Thereafter, I maintained both a geographic and emotional distance from home, which initially brought me some degree of comfort.

As years went by, the distance sustained a sense of relief but not of happiness. I was, in fact, quite a sad young man. I came to learn that people who have been abused as children tend to develop the habit of self-blaming. For some reason, it is easier to accept suffering as the predictable result of your own shortcomings, and therefore something theoretically you might be able to correct, than to acknowledge that you have been dealt a bad hand by the universe and that you are powerless to do anything about it. In any case, I had become remarkably proficient at self-blame. Feeling that all of the things that go wrong in the world around you are your own fault is a sure-fire recipe for perpetual sadness.

It took many years of life as a young adult, and processing of memories on a therapist’s couch, before I recognized that there was a step I could take which would help me to heal the wounds inflicted upon me in childhood. It was to search out and find my father. This seemed an important task in coming to terms with the reality of my situation and reducing the burden of exaggerated self-blame I had taken on.

I undertook the project during the years I was doing residency training, the beginning of the 1970’s, when I was in my late twenties. I had little information about my father other than his somewhat unusual French-sounding surname, “Mafit,” the surname I bore through the first grade in school, and the fact that he had received medical training. Assuming that he was still alive, was practicing medicine somewhere in the United States and that he would have become certified in some medical specialty, I was able to locate a promising candidate by searching the reference section of my medical school’s library. There was an obstetrician-gynecologist in Roseburg, Oregon, named Mafit, whose dates of medical school graduation and of naval service seemed appropriate for my father. I was interested to see that this Dr. Mafit had done his ob/gyne residency at Washington University in St. Louis in the years immediately following the end of the war. That was the time period in which my adoption had been transacted. If this was indeed my father’s record I was seeing, it meant that he would have made the decision to sign the adoption papers while employed, hundreds of miles from where his children were living, as a hospital resident, a position that in those days required literally residing within the hospital’s walls and being available to provide care to the hospital’s patients around the clock. It would have provided little or no salary and he likely would not have been able to hire a lawyer. This would not fully justify his willingness to give up his children, but it went part of the way as an explanation, providing a glimpse of how restricted he was in his ability to act and allowing me to imagine how painful it would have been to be a parent trapped by these circumstances.

I sent off a brief handwritten letter to this Dr. Mafit at his listed office address, saying that I believed him to be my father with whom I had lost touch many years back, and, if my supposition was correct, would he be interested in writing to me? I received an immediate reply (“immediate” for the days of snail mail) saying that he was indeed my father, corroborated by the enclosure of an old photograph of him holding me as a baby. He said that for years he had been hoping I would reach out to him, and he thanked me for doing so and praised the courage he thought it must have taken. He understood the depth of Mama’s antipathy toward him and explained that that was the reason he had not taken the first step. He anticipated I had been told many bad things about him growing up, which he hoped he would have the opportunity to counter. (Actually, I had been told almost nothing about him; the worst I had been told was that he was a man who cared nothing for his children, which the reply letter itself seemed to disprove.) He signed the letter, “your loving father, Ted.”

We wrote letters to each other periodically, he more faithfully and promptly than I, over the following years, the years of his life that remained, and we visited each other on both coasts once every year or so. I learned much about him, although I was, of course, not seeing him from the perspective I would have had as a growing child.

He was a tall, tanned, white-haired man, who spoke slowly and softly and with a western drawl, which belied the enormous drive and energy that lay below the surface. He had carried on a solo practice of ob/gyne in this small city for his entire professional career, which meant he could be called on 24/7, around the clock and around the calendar, to report to the hospital to perform a delivery or emergency surgery.

He was never inclined to take on a partner, or involve himself in a group practice typical of most of today’s ob/gynes. I believe he was, in his heart, a committed loner. He valued his independence; he was one of the original maverick practitioners in Oregon who made the national news when they resigned en masse from the state medical society after it started requiring regular continued medical education as a condition of membership.

He had a number of friends and professional contacts, with whom he had cordial but not close relationships. I suspected he was a man who had difficulty with intimacy. He married three more times after the breakup with my mother, each time to a successively younger woman. He had three daughters with his second wife, my half-sisters, who are about half a generation younger than I. They all had the experience of looking to him as a dad when little, and they told me that he had seemed distant to them in those years.

Ted's second wife, Melba.

It came up once in conversation that one of his teachers when he was in training was Dr. William Masters, who had later acquired national attention for his work, with Dr. Virginia Johnson, on human sexuality. When I asked Ted what Masters was like, he remembered him as “a scrupulously honest man” and “a very dedicated researcher.” He didn’t have much to say about the popular book and I was left with the impression that he didn’t do much sexual counseling in his ob/gyne practice.

In his early years of practice, he had traveled to New York to attend lectures at Cornell Medical School being given by Dr. George Papanicolaou, the originator of the screening test for cancer of the cervix of the uterus now known as the “Pap smear.” Ted wanted to be able to offer this test to his patients, but many medical laboratories didn’t do it; there was a lot of skepticism in the medical community at the time, probably because Papanicolaou himself was a scientist who studied reproductive physiology in monkeys and not a medical doctor. So Ted learned to do the test himself, and, after acquiring official certification, performed it in his office laboratory up until his retirement.

He incorporated elective abortions into his practice after the Roe v. Wade decision made them permissible. He took referrals from the other ob/gyne specialist in Roseburg, who was a Roman Catholic and had personal religious objections to the procedure. Ted himself professed no religion. He did not believe in unlimited access to abortion, however. Any woman who asked him to terminate her pregnancy first had to demonstrate that she had a reasonable plan for avoiding unplanned pregnancies in the future (he would, of course, assist her with this), and she was advised that he never performed a second abortion on the same patient.

He was passionate about his hobby of fly fishing, which he indulged in almost daily. He had used much of the wealth generated from his practice to purchase an estate whose back lawn was bordered by the North Umpqua River, so that he could do fly-casting from his back yard.

Ted was addicted to, but seemingly not impaired by, alcohol. The addiction was integrated into another consuming hobby, winemaking and viticulture. He purchased land for a vineyard adjacent to his home and acquired a second vineyard later, a few miles away. When he retired from his practice, he became a professional vintner. He drank a bottle of wine daily as a matter of course, and he believed it did not affect his ability to do a delivery or emergency operation when called on in his off-hours. I realize this is a claim many would find implausible. I certainly did not perceive any effect from his drinking when we dined together; he remained the quiet, reserved, dignified, soft-spoken man he always was. His colleagues and support staff at the hospital, who had observed his performance over many years, appeared never to have suspected his alcohol use. In his last days, after he was admitted to the hospital’s Coronary Care Unit with a coronary artery occlusion that was to prove fatal, he developed a seemingly bizarre neurological syndrome that mystified the hospital staff. They discussed bringing in an outside neurological specialist to consult. His daughter and wife had to quietly suggest that what they were witnessing was delirium tremens, and that it would disappear if he was given alcohol. To make such a diagnosis on a respected senior member of their medical staff would never have occurred to them.

In addition to the character-defining traits I’ve just outlined, I also learned some things about my father that must, I suppose, be considered trivia, but which I’ve always found endearing:

He was spectacularly good-looking in pictures from his youth, with his dark hair and moustache making him resemble Douglas Fairbanks or Ronald Coleman. Many NY friends to whom I introduced him on his visits here commented on how dashing he was.

His full name was Trowbridge Rudolph Mafit. The Mafits seemed to have a penchant for giving their offspring colorful names. My paternal grandmother’s first name was Theil, and she had had two sisters whose names were Leith and Devere. My three half-sisters were named after them, Andrea Leith, Leslie Theil, and Dana Devere.

Ted had become famous among members of the fly-fishing community for the flies that he designed and crafted himself. One such hand-tied fly was the subject of a feature article in Field and Stream, and it was later marketed commercially as the “Doc’s Fly.”

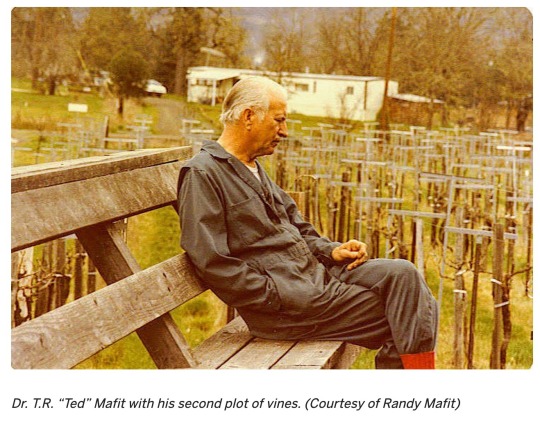

He also acquired fame among Oregon winemakers. The local county museum to this day has on display a bottle of white pinot noir that he produced sometime in the 1970s, believed to be the first of this variety to originate in Oregon.

Ted owned 23 cats at the time of my first Oregon visit, three Siamese inhabiting the house, the remainder domestic short-hairs roaming about his estate. They all had names. He joked that he was emulating, and hoping to surpass, Ernest Hemingway in their number.

It was during his final days that my father and I once again became separated. I actually did not realize it was happening at all, at the time, that he had begun the process of dying. He wrote me two letters describing the coronary events that he had experienced. He somehow managed to use descriptive medical language to minimize the seriousness of his condition; he made it seem as if he would be back on his feet, working his vineyards any day now. I fell for it, and decided I would not plan my next visit to Oregon until he had recovered.

It came as a shock when I was notified that he had died. I flew to Roseburg to attend the funeral. My heart broke when I saw photographs of him in the days before he died, the days when he was writing me the cheery letters; he was gaunt, disheveled, in distress, and obviously a seriously ill man in those photos. I re-read the letters and slowly began to appreciate his artful use of the medical language to alleviate my concern. There was only one unequivocal deception on his part; he claimed in his letters that he was being told he was not a candidate for coronary artery bypass surgery. My sisters and his wife, who witnessed the events in real time, let me know that the opposite was the case. His doctors repeatedly implored him to consent to surgery, and, each time, he adamantly refused.

I’ve concluded that he simply wanted to die alone, and with as little revelatory conversation as possible. He did not want me to come to say good-bye to him in person. It would have been too painful for him. The exposure of his alcoholism on his death bed must have been mortifying to him; he just wanted to slip away quietly.

This seemed to encapsulate the sort of man he was, a man to whom peace and preservation of his dignity was all important. He was not a street fighter like Mama. He could never have taken her on in a brawl.

To return to my original question, the issue of forgiving him for abandoning his parental rights at the time of the divorce now seems irrelevant. What I had earlier yearned for from him was simply not in him to give. And I am at peace with that now.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Binding of Isaac, Revisited

An unpreachable sermon*

Genesis 22:1-14

God tested Abraham. He said to him, “Abraham!” And he said, “Here I am.” He said, “Take your son, your only son Isaac, whom you love, and go to the land of Moriah, and offer him there as a burnt offering on one of the mountains that I shall show you.” So Abraham rose early in the morning, saddled his donkey, and took two of his young men with him, and his son Isaac; he cut the wood for the burnt offering, and set out and went to the place in the distance that God had shown him. On the third day Abraham looked up and saw the place far away. Then Abraham said to his young men, “Stay here with the donkey; the boy and I will go over there; we will worship, and then we will come back to you.” Abraham took the wood of the burnt offering and laid it on his son Isaac, and he himself carried the fire and the knife. So the two of them walked on together. Isaac said to his father Abraham, “Father!” And he said, “Here I am, my son.” He said, “The fire and the wood are here, but where is the lamb for a burnt offering?” Abraham said, “God himself will provide the lamb for a burnt offering, my son.” So the two of them walked on together.

When they came to the place that God had shown him, Abraham built an altar there and laid the wood in order. He bound his son Isaac, and laid him on the altar, on top of the wood. Then Abraham reached out his hand and took the knife to kill his son. But the angel of the Lord called to him from heaven, and said, “Abraham, Abraham!” And he said, “Here I am.” He said, “Do not lay your hand on the boy or do anything to him; for now I know that you fear God, since you have not withheld your son, your only son, from me.” And Abraham looked up and saw a ram, caught in a thicket by its horns. Abraham went and took the ram and offered it up as a burnt offering instead of his son. So Abraham called that place “The Lord will provide”; as it is said to this day, “On the mount of the Lord it shall be provided.”

Some stories depend very little on the element of time to achieve their impact on the reader. Their impact, rather, comes from a single climactic moment, midway through the narrative, that transfixes the reader--a picture in words, full of emotion, that gives the story its meaning. The words leading up to and following the climactic moment serve only to ground it in reality, for if it does not feel real to the reader, its impact is lost.

Take, for example, that stunning moment in Alfred Hitchcock’s film Notorious, that moment when the central character, portrayed by Ingrid Bergman, comes to realize that she is slowly being poisoned to death by her husband, that she is being murdered in full public view and has no way to cry for help or extricate herself from her predicament. Watching the film, we identify with her and experience her profound terror and helplessness at a gut level.

The almost preposterous events that precede this moment in the film—the ring of Nazi scientists operating under cover in Britain, the recruitment of the Bergman character by MI-6 to become a mole, to penetrate the ring, and to marry the head Nazi—serve only to enable us to understand the logic of the climactic moment. To fully experience the terror of the moment we must believe it is real. Its reality depends both on the logic of the way the heroine is currently constrained, and the plausibility of the chain of events that led her into this situation. The audience that appreciates Hitchcock’s artistry—which would seem to be most of us—must override a natural skepticism as we watch the initial events of the film play out, a suspicion that things would never happen that way in real life. If we focus on such thoughts, the climactic moment no longer seems real, and the movie no longer frightens us--or may actually bore us.

This contrasts with other types of stories that consist of a sequence of events, each of which, beginning to end, strikes the reader as true to life. The time element may be very important in these; Shakespeare’s plays are praised for the way they depict the evolution of their characters as the drama plays out. Many bible stories, for example,the Exodus, are of this type. They do not require the reader to selectively suspend disbelief to be appreciated. If the story is a myth or work of science fiction, the actions and feelings of the characters should at least be uniformly in line with what we know of human nature.

One might compare this distinction in story types to sculpture and painting in the visual arts. To view a two-dimensional painting as a depiction of a three-dimensional world, an onlooker must overcome a certain natural skepticism, something that’s not required in viewing sculpture. But paintings have the power to depict truths about the world that are not possible in sculpture. Each may therefore be considered a valid mode of expression in the visual arts.

I consider the Binding of Isaac, the lesson from Genesis, to be a word-picture, in this sense, rather than a story in time. If we take this view of this troubling passage, it gets us off the hook of trying to find meaning in the implausible events and actions that precede and follow the climactic moment. (That moment is, of course, Abraham, poised with his dagger held high above the bound body of Isaac, ready to perform the sacrifice.) We need not interpret the events that lead up to and then away from that moment on the sacrificial altar, because, in a word-picture, these serve only to establish the logical integrity of the predicament in the climactic moment, they need not be important in themselves or hold particular meaning for us. The meaning of the lesson as a whole thus becomes the meaning of that single, powerful image of the raised dagger at the altar.

Before asking what that meaning might be, it’s worth taking note of just how implausible the lead-in narrative actually is. The silent passivity of Abraham here is totally out of character with the feisty Abraham who, six chapters back, has pleaded and bargained with God not to totally destroy Sodom (Genesis 18:16-33). But the meek subservience he displays here seems to me more than just out of character, it seems totally unbelievable of any parent with sound mind and heart. Wouldn’t the first words from the lips of any parent commanded by divine authority to sacrifice their child, be “take me instead”? “I’ll take my own life on the altar, but let my child live”?

Then we have the implication of the ending paragraph, the angel’s cancellation of God’s command and the apparent restoration of all things to their original state, as a ram is sacrificed and Abraham and Isaac head home. A modern reader, familiar with psychology, would recognize the profound implausibility here. Things cannot just go back to normal. A child who has experienced nearly being murdered by his father would be mentally traumatized for life. Abraham would likewise suffer enormous guilt at his failure to resist committing a terrible act, and likely debilitated the rest of his life.

These implausibilities and inconsistencies are frequently cited by religious scholars who discuss this biblical text. I find I’ve never learned anything myself from their interpretations of them. The problem with focusing on the contradictions of the preface and ending sections of the lesson is that they make the climactic moment seem unreal. If so much of this story is preposterous, how can we believe that the story as a whole holds any truth for us at all?

Is it possible there is no deep meaning to this story, that it became incorporated into the biblical writings, Darwinian fashion, simply because it is so horrible and grotesque that it has captivated the attention of all who’ve read it, including the ancient biblical scribes who reproduced it through generations? Has it survived the centuries because it mesmerizes us, the way a smoking, recently wrecked car at the side of a highway captures the attention of the drivers passing by, all of whom slow down their cars and stare—to no purpose at all?

I don’t think this is true. I think that the climactic moment of this story about Abraham and Isaac holds profound truth for us, a profound but dark truth about what it means to be a human being.