Text

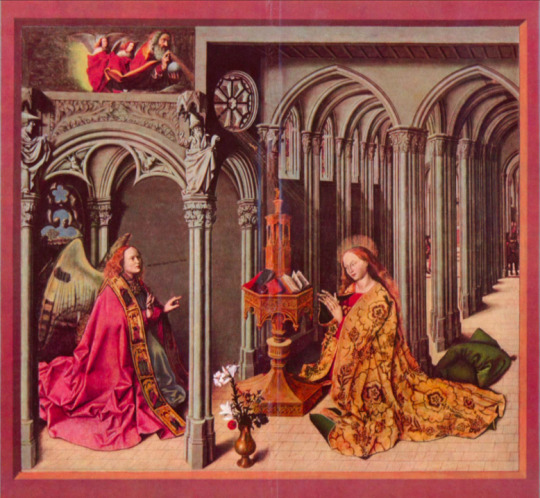

The Aix Annunciation mysteries

A bit of 🎨 and 😈 today!

Emile Henriot, a french writer, reported - or came up with - a strange gossip about The Aix Annunciation in his novel 𝘓𝘦 𝘥𝘪𝘢𝘣𝘭𝘦 𝘢̀ 𝘭’𝘩𝘰̂𝘵𝘦𝘭 (1919) : this sacrilege painting has been designed with satanic intentions (and even painted backwards in some versions!).

🕵️♀️ Some facts:

The triptych is attributed to Barthélémy d’Eyck. It was commissioned in 1442 by Pierre Corpici, a local cloth merchant, for his chapel’s altar in Saint-Sauveur cathedral in Aix-en-Provence (southern France). It was then divided in 6 pieces, the central panel was moved to the Eglise de la Madeleine, still in Aix, and you can now see it in the Musée du Vieil-Aix.

The annunciation is a very common theme in Christian painting and it had been quite codified through the century, this version may differ a bit from the images we have in mind in the first place, that would explain the fantasies about it. Henriot considered that the painting was unholy in many ways.

First thing, if you zoom on the ray of light, instead of the usual dove symbolizing the Holy Spirit, you’ll see a tiny human holding a cross (the 𝘏𝘰𝘮𝘶𝘯𝘤𝘶𝘭𝘶𝘴, « the little man » in Latin), kind of diving towards the Madonna. It’s probably not the most common representation but it’s not that usual before the Council of Trent forbids this depiction (see the Merode Altarpiece and other medieval paintings for exemple).

Others things that excited the writer’s imagination:

Gabriel’s wings look like they’re made of owl feathers, a bird considered as a bad/unlucky omen.

The light that radiates from God hits the head of a little monkey (crowning the reading desk) before it shines on the Virgin.

Henriot also considers that God’s gesture is « unliturgical », his fingers’ position is obscene.

The expressions on the characters’ faces do not suit a sacred painting.

You can also notice the bats sculpted in the architectural ornements surrounding the Archangel: not suitable as well, according to Henriot.

Even the flowers in the vase are allegedly unholy: Henriot identifies belladonna and aconit, flowers used by witches and other evil creatures. We can also see what looks like digitalis (also known as Virgin’s glove), roses and lilies, which are frequently associated with the Virgin Mary so it’s probably actually no big deal…

The story tells that the patron refused to pay the price they agreed on beforehand. The painter produced a demonic and blasphemous artwork in order to avenge himself and to punish the penny-pincher.

🖼️: 𝘛𝘩𝘦 𝘈𝘪𝘹 𝘈𝘯𝘯𝘶𝘯𝘤𝘪𝘢𝘵𝘪𝘰𝘯 (detail of the central panel), attributed to Barthélémy d’Eyck, 1443-1445, Musée du Vieil-Aix.

📚 Selected sources (in french):

Emile HENRIOT, Le Diable à l’hôtel ou les plaisirs imaginaires, Paris, Emile-Paul Frères, 1919.

Jean-Louis VAUDOYER, Les peintres provençaux : de Nicolas Froment à Paul Cézanne, Paris, La jeune Parque, 1947.

Louis-Philippe MAY, « L’annonciation d’Aix » in Provence Historique, 1954, tome 4, fascicule 16, pp. 82-98.

René ALLEAU (dir.), Guide de la France mystérieuse, Paris, Sand, coll. Les guides noirs, 2005.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mahler street’s ghost

I’m sharing today a short ghost story/urban legend that I discovered online. It’s probably more of an excuse to write about the tragic story of one of Marie-Antoinette’s most loyal friend, Marie-Thérèse-Louise de Savoie-Carignan, 𝘗𝘳𝘪𝘯𝘤𝘦𝘴𝘴𝘦 𝘥𝘦 𝘓𝘢𝘮𝘣𝘢𝘭𝘭𝘦.

That ghost thing is not much documented, unlike Lamballe’s last moments: her death has been described in many versions and with many macabre details.

---

Our narrative begins in the throes of the French Revolution, with the events of August 10th 1792. The royal family is incarcerated in the Feuillant convent, then in the Temple Tower after the assault on the Tuileries.

The Princesse de Lamballe follows the queen in custody, but the royals are soon isolated from their inner circle. She’s transferred a few days later in the 𝘱𝘳𝘪𝘴𝘰𝘯 𝘥𝘦 𝘭𝘢 𝘍𝘰𝘳𝘤𝘦. The building doesn’t exist anymore, but it was located in the current Mahler street (at the number 3).

𝘓𝘢 𝘍𝘰𝘳𝘤𝘦 is one of the prisons targeted by the outraged crowd during the September Massacres, five days of mass summary executions that led to the death of up to 1400 prisoners (nearly half of the jail population of Paris).

The Princesse de Lamballe meets the same fate: she’s slaughtered by the crowd after a sham trial on September 3rd.

She has been stabbed to death as soon as she stepped out of the improvised court. She’s then decapitated, her head is placed upon a spike and displayed in the streets. Some sensationalists texts reports that her heart is ripped out of her chest, her breast and genitalia chopped off.

The mutilated corpse is then supposedly left among the piles of corpses that lie in the area.

Legend has it that the Princesse de Lamballe is still wandering in Mahler street, looking for her head, heart and body parts.

🖼️: 𝘓𝘢 𝘮𝘰𝘳𝘵 𝘥𝘦 𝘭𝘢 𝘗𝘳𝘪𝘯𝘤𝘦𝘴𝘴𝘦 𝘥𝘦 𝘓𝘢𝘮𝘣𝘢𝘭𝘭𝘦 (detail), painting by Maxime Faivre, 1908, Musée de la Révolution Française.

📚 Selected sources:

Louis-Sébastien MERCIER, 𝘓𝘦 𝘕𝘰𝘶𝘷𝘦𝘢𝘶 𝘗𝘢𝘳𝘪𝘴, Paris, Fuchs, Pougens et Cramer, 1797.

B. C. HARDY, 𝘛𝘩𝘦 𝘗𝘳𝘪𝘯𝘤𝘦𝘴𝘴𝘦 𝘥𝘦 𝘓𝘢𝘮𝘣𝘢𝘭𝘭𝘦; 𝘢 𝘣𝘪𝘰𝘨𝘳𝘢𝘱𝘩𝘺, Londres, A. Constable, 1908.

https://www.lepoint.fr/culture/journees-du-patrimoine-les-fantomes-de-paris-2-la-princesse-de-lamballe-19-09-2015-1966153_3.php

https://www.lhistoire.fr/septembre-1792-de-la-rumeur-au-massacre

#french#french stories#french revolution#la revolution#the revolution#princesse de lamballe#secretparis#mysterious paris#paris unveiled#Paris#marie antoinette#ghosts#ghost stories

0 notes

Text

La Fontaine hideuse

Our tale takes place in the village of Beuvry (Northern France). The area was not exactly welcoming (surrounded by marshes and ponds) but it was somehow the place some mysterious lord chose as his residence. The story tells that he lived here, in a gloomy castle overhanging the water, during 20 years. He never stepped out of it - and it seems fair to say that no one dared to enter it.

No one ever saw him in those two decades. Actually, no one ever saw a living soul around here, except for the men guarding the castle but the fact that they were unable to speak the common tongue only made things worse.

The only thing coming out the castle were some petrifying sounds on every Christmas Eve: you could hear people screaming, moaning and weeping, some others laughing hysterically. Everything was back to silence at midnight and stayed so until the next Christmas.

The villagers soon believed that the lord was conspiring with some evil forces, some even thought that he was the Devil himself.

Anyway, they carefully stayed away from this place, even avoided to look in that direction. Those who talked about this strange case mysteriously disappeared so no one dared to discuss it any longer.

On a certain Christmas Eve, the screamings and cries became particularly loud before stopping as they usually did. The villagers discovered the next morning that the castle had vanished into thin air. There was no trace of it but they found a new water spring at this exact location and named it la 𝘍𝘰𝘯𝘵𝘢𝘪𝘯𝘦 𝘩𝘪𝘥𝘦𝘶𝘴𝘦 (which you can translate as horrible fountain).

🖼️: 𝘗𝘦𝘢𝘶 𝘥’𝘢̂𝘯𝘦 (detail), illustration by Gustave Doré published in 𝘓𝘦𝘴 𝘊𝘰𝘯𝘵𝘦𝘴 of Perrault (Paris, J.Hetzel) 1862.

📚 Selected sources (in french):

Jacques COLLIN DE PLANCY, Dictionnaire infernal, Paris, Plon, 1863, p. 663.

René ALLEAU (dir.), Guide de la France mystérieuse, Paris, Sand, coll. Les guides noirs, 2005.

#frenchstories#frenchmyths#frenchfolklore#folklore#french folklore#french tales#occult#devil stories#devil#gloomy#dark#twisted tales#french#historical

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The 13th dancer

There are many french stories involving the Devil hiding amongst a ball’s guests or joining some festivities (especially in the Breton folklore). I discovered this one lately and never heard of it so I thought of sharing it here!

The story takes place in Eastern France, in the small city of Dôle (now in 𝘉𝘰𝘶𝘳𝘨𝘰𝘨𝘯𝘦-𝘍𝘳𝘢𝘯𝘤𝘩𝘦-𝘊𝘰𝘮𝘵𝘦́), during the annual celebrations called 𝘍𝘦̂𝘵𝘦𝘴 𝘥𝘦 𝘭𝘢 𝘚𝘢𝘪𝘯𝘵-𝘑𝘦𝘢𝘯 (feast of Saint-John) which you can compare to the summer solstice festivities. It’s still celebrated to this day in France, people usually gather around bonfires.

12 dancers were selected amongst the young people to perform on that night. They would dress up as devils, scream and dance frantically in the streets.

Legend has it that one night, a 13th dancer was spotted and couldn’t be found at the moment they were supposed to drop their masks. People thought that Devil himself came to dance amongst the living.

This dance tradition has been forbidden after that mysterious incident (probably around the 16 or 17th century).

🖼️: 𝘋𝘦𝘴𝘤𝘳𝘪𝘱𝘵𝘪𝘰𝘯 𝘥𝘦 𝘭’𝘢𝘴𝘴𝘦𝘮𝘣𝘭𝘦́𝘦 𝘥𝘦𝘴 𝘴𝘰𝘳𝘤𝘪𝘦𝘳𝘴 𝘲𝘶’𝘰𝘯 𝘢𝘱𝘱𝘦𝘭𝘭𝘦 𝘚𝘢𝘣𝘣𝘢𝘵 (detail), engraving from the 18th century, based on an original from Bartholomaeus Spranger.

📚 Selected sources (in french):

Daniel BIENMILLER et Michelle MILLET, Univers folklorique et Sorcellerie à Dôle aux XVIe et XVIIe siècles, Dôle, Bibliothèque municipale, coll. Les Cahiers Dôlois, 1977.

Nigel E. WILKINS, La musique du diable, Liège, Mardaga, 1999, p. 65.

René ALLEAU (dir.), Guide de la France mystérieuse, Paris, Sand, coll. Les guides noirs, 2005.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Paris’ death “museum”

Did you know how the term « Morgue » came to mean what it means today? I’m sharing with you today a quite macabre anecdote that will please Parisian enthusiasts as well as etymology lovers. The primary meaning of the word morgue is face or attitude in Old French.

Our story begins in the medieval Paris, in the fortress of Châtelet, a place that was at this time some kind of administrative and judiciary center. It naturally contained prisons for that reason. The new prisoners were first brought in an open cell so the guard could stare at them (Old French verb morguer) and memorise their facial features in case of escape or offence. The term gained a new meaning and referred by extension to the cell the newcomers were transiting by just before being permanently incarcerated. In 1718, the French official dictionary provides us a new information about the use of this cell : it was now the place where unknown dead bodies found on the streets or drowned in the Seine were stored. That place was open to the public in order to identify the corpses.

🔎 May 10th of 1741 🔎 According to the memorialist Barbier, the whole Paris rushed at the morgue to see an unusual display: the head of a man had been found in a cooking pot, boiled with some bacon, herbs and spices.

In 1804, the morgue is relocated on the Île de la Cité, in the very heart of Paris. The building became some sort of a stop-off point (for the workers on their way to work, or on a lunch break, for the women on their way to the nearby market Marché-Neuf, for the children playing around). You have to imagine an endless stream going in and out, all day long.

The staged dimension of the morgue intensifies in the 19th century: after a relocation in 1864 (quai de l’Archevêché, still on the Île de la Cité), a larger building is erected. The exhibition room could display 12 corpses at the same time, laying on marble slabs.

Some texts report that the crowd was queuing in the street and literally piling up against the glass windows to stare into death (up to 68 000 entries a day, according to B. Bertherat). It became a real must-see as well as a touristic attraction, a sort of museum of the death and a real business, listed in every decent travel book.

That questionable solemnity contributed to end those morbid curiosity urges: in 1907, the morgue of Paris closed its doors to the public.

📚Selected sources (in french):

Edmond Jean François BARBIER, Chronique de la régence et du règne de Louis XV (1718-1763), Paris, Charpentier, 1858, p. 277.

Edouard FOURNIER, Enigmes des rues de Paris, Paris, E. Dentu, 1860, pp. 153-169.

Charles Jean Firmin MAILLARD, Recherches historiques et critiques sur la morgue, Paris, Adolphe Delahays, 1860.

Bruno BERTHERAT, « Visiter les morts. La morgue (Paris XIXe siècle) » in Hypothèses, vol. 19, no. 1, 2016, pp. 377-390.

French Minister of Justice website.

🖼️: Inside view of the Morgue in 1845, drawing based on painting from Carré, 1845, BNF, Paris, France.

#french folklore#french tales#french stories#paris#secretparis#creepystories#creepy stuff#macabre#morgue#paris unveiled#mysterious paris#paris mysteries

0 notes

Text

The Black Hunter of Chambord

Some texts report the presence of a ghostly hunter haunting the famous estate of Chambord.

We have to go back to times prior to the construction of the emblematic castle that we know today: the estate was then known by the name of Montfrault. It included a hunting lodge, or maison de plaisance, property of the counts of Blois. Legend has it that if you go around the location of the former lodge at midnight, you will see a hunter dressed in black, followed by his pack of hounds.

That hunter is usually identified as a tenth-century lord: Theobald I, first count of Blois, also known as the Trickster (French: Thibault Ier Blois dit le Tricheur). Theobald is depicted as an evil and cruel man who earned his nickname by giving himself the title of Count of Blois - and allegedly by taking some lands around Chambord by force. He also terrorised the locals by leading raids in the area.

The story tells that one day, Theobald stabbed a priest in full mass after he began the office without waiting for his lord to return from the hunt.

According to the tale, the Count had to answer from his sins at the moment his death and has been condemned to hunt endlessly in those woods without being able to catch a single prey.

On very windy days, you can hear the uproar of this ghost hunt, moving to the neighboring domain of Bury, then returning back to Montfrault.

This tale displays the recurring elements of the Wild Hunts, which is a very common theme in European folklore. Some variations of this myth have been identified in the area, often referred to as Chasses à Ribaut (chasse means hunt / Ribaut may be a distortion of the name Thibault).

📚Selected sources (in french):

Jean-Jacques BOURRASSÉ, « Chambord » in Résidences royales et impériales de France, Tours, Mame, 1864, pp. 312-313.

Louis de la SAUSSAYE, Le Château de Chambord, Blois, 10th ed., 1864, p. 36.

Bernard EDEINE, La Sologne: Documents de littérature traditionnelle: Contes, légendes, … Paris-La Haye, Mouton, 1974, pp. 55-56.

Xavier PATIER, Le roman de Chambord, Monaco, Editions du Rocher, 2019.

🖼️ (not related to Chambord directly): The Wild Hunt (unfinished), by Johann Wilhelm Cordes, 1856-57. Benhaus Museum, Lübeck, Germany.

3 notes

·

View notes