Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

The Grape Riots and the Agricultural Reform Movement of California

1. Introduction:

It is the 1930's in California and many families are starting their workday just before the sunrise to leave for the lettuce and grape fields that span the great valleys that cover state. They would have to endure a long workday for outrageously low wages to barely survive. The majority of these families were immigrants and migrants of all backgrounds, spanning from the Mexicans to the Filipinos. Families would have their children drop out of school at ealry ages to help secure funds for the family. When their work in the area was done, they would pack up their belongings and travel to the next rural town looking for more work. This was sadly the reality for many across the state untill three dacades later when revolutionist like Cesar Chavez and Larry Itliong started to fight for reform of the state's agricultural labor. They started with the boycott of products like grapes and lettuce at general goods stores across California in the 1960's and an assortment of flyers and posters educating the public on the issue with the state of agricultural production and the mistreatment of the many laborers. It took another decade untill the Agricultural Relations Act was passed in 1975. This act unfortantly was ineffective at protecting the Unions and the workers who formed them since nothing was inforced or regulated. In this Journey Box we will explore the trails and tribulations of the Agricultural Reform movement, the forgotten filipinos who fought for it, and why it was deemed unsuccesful for a while.

2. Index:

1. Introduction

2. Index

3. Filipino Farm Workers (Photograph #1)

4. Delano Grape Strikers (Photograph #2)

5. NPR’s “Memories Of A Former Migrant Worker” (Participant Account #1)

6. NPR’s “Grapes of Wrath: The Forgotten Filipinos Who Led A Farmworker Revolution” (Participant Account #2)

7. Grape Boycott Flyer (Artifact #1)

8. Boycott For Democracy Poster (Artifact #2)

9. Summary

10. Sources

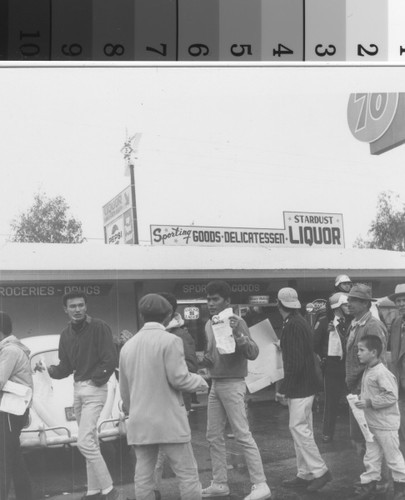

3. Photograph #1

A photograph of Filipino Farm workers picking lettuce, Nagano Farm, Morro Bay, California, ca. 1930.

Questions:

- Why do you think the majority of farm workers were immigrants or migrants?

- What are some of the day to day conditions the farm workers could be experiencing out on the fields?

- Why was this kind of work popular in the valleys of California?

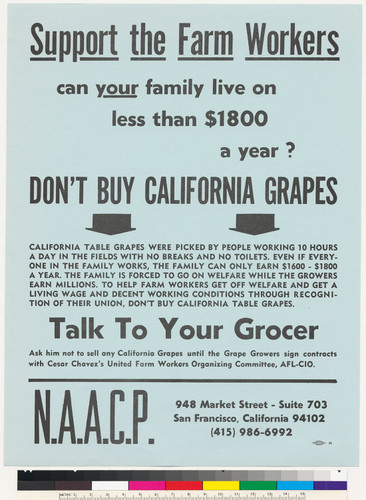

4. Photograph #2

A photograph of Delano Grape Strike picketers in Delano, California, February 1966.

Questions:

- What do you notice about the makeup of the Delano Grape Strike picketers?

- Why is it called the Delano Grape Strike, what could they be striking against? Consider the importance of the location of the strike as well.

- This is one of many strikes against farm owners and ranchers at the time. What do you think was the general public opinion on the matter at the time?

5. Participant Account #1

The following are a collection of excerpts from NPR’s “Memories of a Former Migrant Worker” This technically is not a participant account but since filipinos were so disregarded within the history of the movement this Filipino Historian was the best I could find

Felix Contreras: You were raised in a migrant farm worker environment. Can you describe what that was like?

Luis Contreras: First of all, we didn't have a permanent residence. We traveled in a truck and we lived mostly in a tent on the road between California and Kansas.

Because we were migrants, our schooling was incomplete. We would arrive in a town after school started and leave before the school year was over. We didn't always have the basic necessities of life, like being able to take a bath regularly.

Because we often had to set up our tent in the country, we ate a lot of what we found growing in the wild — fruits, some vegetables. If we were in one place long enough we could plant a garden and eat what we grew. Later, after we stopped moving and settled down in Sacramento (California) my mother would sometimes complain that our diet was better in the country with access to fresh food.

We also worked very long hours, often from sun up until sun down. The entire family, children included. As a child you think it's just normal life, nothing out of the ordinary. We didn't think we were working especially hard. It was just a normal life for us.

Felix Contreras: So things like child labor laws didn't exist back then?

Luis Contreras: There were child labor laws, but here's how migrant families worked it: When we were out in the fields you could see a child labor officer driving up along those dirt roads from at least a mile away. Plus they were usually driving a government car, so it was easy to spot them. The kids would leave the fields, gather around the family truck, then go back to work after the child labor office left the area.

Looking back, I think it was in the interests of the ag. industry to not have the child labor laws enforced because we did a lot of work as children. It was a different time. It was a different way of thinking among people who did agriculture work — meaning, there wasn't much of an interest in the welfare of the field worker.

Questions:

- Why do you think this harsh lifestyle was so normalized for migrant families at the time?

- Why do you think the agriculture industry did not care about enforcing labor laws and what do you think made them decide to enforce them now?

- Think about the present and consider how modern migrant and immigrant families live today. In what ways has life improved for most families and what are the modern problems they face?

6. Participant Account #2

The following is from NPR’s “Grapes of Wrath: The Forgotten Filipinos Who Led A Farmworker Revolution”

Perez is outraged that this history is not known, because the actions those Filipinos took improved her family's lives. "I mean, I'm extremely proud that Cesar Chavez was the right face at the right time, but a lot of the dirty work was already done."

For decades the migrant, bachelor, Filipino farmworkers – called Manongs, or elders — had fought for better working conditions. So in the summer of 1965, with pay cuts threatened around the state, these workers were prepared to act, says historian Dawn Mabalon.

"They're led by this really charismatic, veteran, seasoned, militant labor leader Larry Itliong," she says.

He urged local families in Delano to join Manongs in asking farmers for a raise. The growers balked. Workers gathered at Filipino Hall for a strike vote.

"The next morning they went out to the vineyard, and then they left the crop on the ground, and then they walked out," Mabalon says.

Cesar Chavez and others had been organizing Mexican workers around Delano for a few years, but a strike wasn't in their immediate plans. But Larry Itliong appealed to Chavez, and two weeks later, Mexican workers joined the strike.

Soon, the two unions came together to form what would become United Farm Workers, with Larry Itliong as the assistant director under Chavez.

Mabalon says, "These two groups coming together to do this? That is the power in the Delano Grape Strike."

It took five years of striking, plus an international boycott of table grapes, before growers signed contracts with the United Farm Workers.

Those years weren't easy: on strikers, families, or Delano.

Questions:

- Why do you think the Filipinos are usually disregarded when talking about the "Farmworker Revolution”?

- Why do you think the Mexican workers didn't plan to strike immediately, what could they have done instead?

- Does the Farmworker Revolution remind you of any modern movements where people from all background have united to fight for a just cause?

7. Artifact #1

A NAACP flyer calling for support for the grape boycott, 1965.

Questions:

- Who do you think the target audience was for this flyer?

- How impactful do you think boycotting California Grapes was for Cesar Chavez’s farm work reform movement?

- Do you think grocers would try and avoid certain grapes or choose to ignore the boycott?

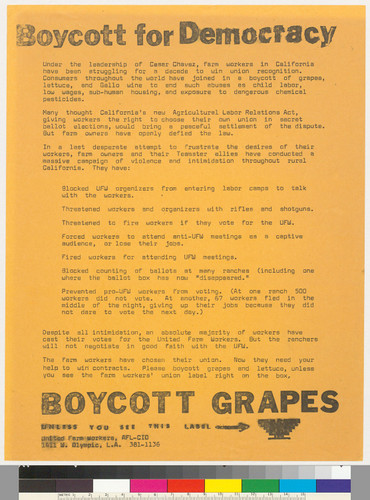

8. Artifact #2

A poster calling for a “boycott for democracy” of grapes, 1975. (transcript here)

Questions:

- Why do you think Agricultural Labor Relations Act failed in protecting the farm workers?

- Why do you think the ranchers and farm owners are refusing to work with the UFW?

- Knowing that the years of protesting and boycotting did little to reform the state of Californias Agricultural laborers. Why do you think they continue to use boycott as an outlet for achieving their goals?

9. Summary:

I chose to cover the Agricultural Reform Movement of California since it is something that hits close to home for me. My family originated from the valleys of California and my Grandpa was one of those immigrant workers who came to the United States for a better life and was met with harsh work conditions and lack of childhood. He would always tell me about how he dropped out of 3rd grade to go work in the fields and ended up losing one of his fingertips at the age of twelve while working. I think this topic would be relevant to many students since they themselves may have family members who were immigrants or be one themselves. They have heard the same stories countless times while growing up. As far as how this can be integrated into other subjects, students could write a personal narrative in the eyes of a migrant child growing up in the 1960s during the movement for English Language Arts. This journey box perfectly addresses the ideas of "A" history not "The" history since we discuss the often not talked about Filipino involvement and the Latin root word of education since we are inviting students to draw out their own thoughts and ideas on the movement.

10. Sources:

Photographs and Artifacts: https://dp.la/primary-source-sets/the-united-farm-workers-and-the-delano-grape-strike

Personal Account #1: https://www.npr.org/sections/pictureshow/2010/10/08/130425856/cesar-chavez

Personal Account #2: https://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2015/09/16/440861458/grapes-of-wrath-the-forgotten-filipinos-who-led-a-farmworker-revolution

6 notes

·

View notes