Text

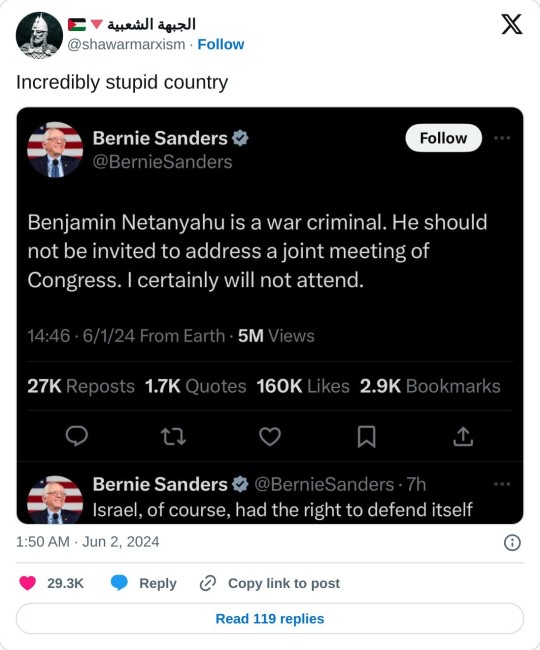

Bernie Sanders is the only prominent US politician making the case against Israel, and he's doing it persuasively. How does getting mad at him for not putting himself across radically enough (relative to US opinion) actually help Palestinians?

23K notes

·

View notes

Text

'you are a pattern' means that is still you getting strangled with garotte wire

The teleporter problem is so funny to me because there is like zero reason why it has to annihilate the guy who walks into the entrance. It could just print the guy out on the other end and be done with it. But its like nah man we need to hook this matter replicator up to a Human Disintegrator 6000 because otherwise we might have to answer uncomfortable questions about our identity

413 notes

·

View notes

Text

Suppose, through some future advance in medical technology, you could be sawn in half, both halves shipped to New York, stitched back together again, and go about your life as normal. Now suppose you're split into a million parts. Suppose you're split into your component atoms and reassembled. How many parts do you need to be split into you for it to stop being you and become instead a Frankenstein's monster made out of you?

If the answer is that it would continue to be you even if it was split down to atoms, then why would it matter which atoms are used, as long as they are assembled in the same pattern? They're all identical, after all. You are a pattern, not your physical stuff, so a teleporter really is a teleporter, even though it's just a matter replicator attached to a disintegrator.

Wanting to avoid there being two of me is a completely reasonable concern, as anyone who has met me IRL will attest.

The teleporter problem is so funny to me because there is like zero reason why it has to annihilate the guy who walks into the entrance. It could just print the guy out on the other end and be done with it. But its like nah man we need to hook this matter replicator up to a Human Disintegrator 6000 because otherwise we might have to answer uncomfortable questions about our identity

413 notes

·

View notes

Text

In sociology and economics, a common way to mathematically model preferences is via weak orderings, which have several equivalent formulations:

1. As a strict partial order for which incomparability of elements is a transitive relation. In this formulation, a < b represents "b is strictly preferred to a", and "a incomparable to b" represents indifference between a and b.

2. As a total preorder, i.e. a total and transitive but not necessarily antisymmetric relation. In this formulation, a \leq b represents "b is preferred at least as much as a", and consequently a \leq b \land b \leq a models indifference.

3. As a utility function f with codomain the real numbers, where f(a) < f(b) represents "b is preferred to a", and f(a)=f(b) represents indifference.

It's clear that (3) is capable of conveying more information than the other formulations, since it can encode not just preference but degree of preference. For the purpose of formalizing a weak ordering, though, this extra information is forgotten.

The point of this post is mainly to say that I do not think weak orderings are a sufficient model for human preferences. I don't think they're terrible, and I think there are domains in which it's reasonable to model preferences via weak orderings, but I also don't think the model is perfect—it is not good enough to represent the ground truth of human psychology, and this should be kept in mind in any applications.

In particular, zooming in on formulation (2): I think the assumption of totality is grievously wrong. It is not in fact the case that humans either have a clear prefer or are indifferent between any two arbitrary options put in front of them. Far from it! Very often people might experience indecision over preferences, that is to say they directly experience two options a and b to be incomparable in a literal sense. Sometimes this is due to lack of information, but sometimes it is inherent: I can think of choices wherein, even in possession of full knowledge of the consequences of options a and b, I would not be able to decide which I preferred—but would certainly not be indifferent between the options!

These "impossible choices" have variously been dramatized and represented in fiction as part of the human condition, and on a more mundane level I think they often occur in everyday life. A not uncommon occurrence, I think, is that a and b are incomparable to each other, but both are strictly dispreferred to inaction, and so when push comes to shove some ad hoc procedure is employed to select between the two. In dramatic terms we might be unable to decide which of our children to save from certain death, but in a more mundane scenario we may simply be unable to decide whether we want to eat an apple or a banana for lunch—both offer different experiences, which are not exactly commensurable with each other—and only end up picking one (via some ad hoc, unprincipled mechanism) on the grounds that either choice is preferable to not eating.

If you've ever been deeply torn between two choices, and found that while neither appears strictly better than the other you would not feel content to choose between them with a coin flip, you have experienced preference incommensurability! This is not the same thing as indifference, either emotionally or practically (in terms of people's behavior), and if your model of preferences cannot differentiate between indifference and incommensurability it is an insufficient model.

We could, in light of this, relax the definition from a total preorder to a partial preorder, and I think this would be somewhat better—although it plainly makes the math harder. But I'm not sure even that would be sufficient; the human experience of wanting is very complex and more granularity may be needed to model it in a way that feels "psychologically adequate".

I don't think these facts, at the end of the day, have too much bearing on domains like economics, where one is working at a low level of granularity with regard to people's preferences anyway. But I'm not a domain expert so I can't say. What I am trying to say is that I think these facts are fairly disastrous for preference utilitarianism as an account of underlying ethical truth. And, as a preferentialist sensu lato about ethics, I regard this as a major mark against the viability of utilitarianism generally.

#I completely agree with all these criticisms that utilitarianism is on ontologically shaky ground to put it mildly#but I am not sure any ethical theory could be on solid ontological ground when you look closely#though maybe they could be less susceptible to this critique than utilitarianism#ultimately you're going to need some kind of theory of what people want for a remotely palatable ethical theory#and I'm not sure there even is a ground truth to how human preferences work#maybe at some point we need to just ignore the cracks in our theories and pretend it all makes sense to avoid confronting absurdity#the other reason is that doing anything other than utilitarianism feels intuitively very wrong for most tradeoffs in a way I might post abo

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Is there any notion of animal welfare that's remotely reasonable? The obvious approach of wanting animals to have rights like humans leads to absurdities like having to hunt all predators to extinction and feeding your dog a vegetarian diet.

The closest I've heard is the idea of whether animals can exhibit natural behaviors, but that still seems a bit contrived—why should what happens to them naturally be the best possible thing for them? And what does 'natural behaviors' even mean for pets or house spiders?

Also, natural behaviors for cats is to starve to death if they get injured, so can we not object to an owner starving their cat to death? Or is it about giving the animal a fighting chance somehow? If so, why? Natural behaviors for many insect species involve being taken over or eaten from the inside by parasitoid wasps, and it seems odd to describe that as good animal welfare. If someone gets parasitoid wasps to lay eggs inside bugs because they enjoy watching the bugs suffer, is there no animal welfare objection to that? My gut reaction is that there should be.

I think this whole landscape of debate is an embarrassment because people want to justify, e.g., why eating meat is ok but bestiality isn't in order to continue with their lives as before, and I would like to know if there is a sensible version of it.

0 notes

Text

Disagreeing with a community on at least one issue is very valuable because you can see from the outside whether they're using reasonable sources and arguments for what they believe.

1 note

·

View note

Text

I'm really not trying to put forward a view here, I'm genuinely curious. But surely you can see 'it happened once before (and didn't go well)' isn't a terribly convincing argument? What is the sophisticated argument for Russia being likely to invade other European countries in the absence of NATO?

When it's third-world anti-Americanism it's usually like "yeah, sorry, I would also prefer if my country was not doing that, that's fucked"

When it's European anti-Americanism it's usually like "yeah, actually I think maybe we should withdraw from NATO just to see what happens"

243 notes

·

View notes

Text

Some analysis of the ideology/internal politics of the Russian government, perhaps? Because that really isn't enough; lots of countries have started one war on spurious grounds and not started a follow-up war.

When it's third-world anti-Americanism it's usually like "yeah, sorry, I would also prefer if my country was not doing that, that's fucked"

When it's European anti-Americanism it's usually like "yeah, actually I think maybe we should withdraw from NATO just to see what happens"

243 notes

·

View notes

Text

This isn't an argument rooted in evidence. What's the evidence that Putin would invade other European countries?

When it's third-world anti-Americanism it's usually like "yeah, sorry, I would also prefer if my country was not doing that, that's fucked"

When it's European anti-Americanism it's usually like "yeah, actually I think maybe we should withdraw from NATO just to see what happens"

243 notes

·

View notes

Text

Is NATO actually protecting Europe from anything? it seems like Russia is the only plausible aggressor but I don't know if they'd even want to invade any more European countries or if the Ukraine war is about a specific hangup Putin has about Ukraine. And presumably they don't want to replicate the Ukraine war anyway. I guess NATO protects trade routes? but Europe could do that on its own.

When it's third-world anti-Americanism it's usually like "yeah, sorry, I would also prefer if my country was not doing that, that's fucked"

When it's European anti-Americanism it's usually like "yeah, actually I think maybe we should withdraw from NATO just to see what happens"

243 notes

·

View notes

Text

I haven't really got all my thoughts sorted out here, so maybe I'll arrive at different conclusions later, but:

When you start talking about long timescales you run into a problem of stability of preferences: you won't be the same person in 3^^^3 years—you probably won't have anything in common with yourself then—so it's basically like you're not benefiting at all. And what would it even mean to get what you want for all that time? Won't you eventually get bored? Won't you eventually decide that you've seen all there is to see and that what you want is for it to be over, or perhaps to be functionally mortal again?

I don't think these are avoiding the question, like saying you'd untie all 6 people in the trolley problem. I think it's a fundamental metaphysical issue with the amount of joy that a human being is capable of experiencing in their lifetime—even an unnatural lifetime. So one might correctly intuit that nothing would make you take lottery A, not because expected utility isn't a sound basis for decision making, but because there genuinely isn't anything that could make lottery A have a positive expected utility.

@gamingavickreyauction Oh, right, here's one trouble I have with expected value maximization:

Say there's a lottery A, and in this lottery I have a 1 - ε chance of getting my right arm ripped off and going blind. This is pretty bad. Say it has utility to me N, where N is a negative number of large magnitude. There is also an ε chance of something really really good happening, something extravagantly good like world peace and I live forever and get everything I want. Let's say the utility of this outcome to me is M. So the expected value of playing this lottery is E(A) = N(1 - ε) + Mε.

Now, N is pretty big, but it's still finite. Getting my right arm ripped off and going blind would pretty thoroughly fuck up my life in every way that I care about. So I really don't want that. But it's not the Christian hell, it's not infinitely bad. Fix ε to be some very small number 0.00000000000001 or whatever. With N and ε fixed, we can always choose some M such that E(A) is greater than zero. In fact, we can choose M so large that E(A) dominates the expected utility of my entire life.

Suppose I was offered a chance to take the lottery A with this ε. Would I do it? I strongly suspect that I would not, no matter how big you make M. You can chalk this up to a failure of reasoning on my part, a failure to truly internalize the bigness of M. But it feels to me like, no matter how big you make M, participating in the lottery would basically just be signing up to get my arm ripped off and go blind. Like that's just definitely what would happen, I would totally not get M. The expected value is a mathematical abstraction, and I'm not signing up to more-or-less certainly get dismembered over an abstraction. I think I would not accept this lottery! And I think probably most people wouldn't.

I believe this goes against one of the Von Neumann–Morgenstern axioms.

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

When you violate the Von Neumann Morgenstern axioms consistently, you can be exploited by repeated offers of lotteries:

If you'll choose guaranteed 1 util over 999/1000(0)+1/1000(2000) then you'll choose 999/1000(0)+1/1000(2000) over 998/1000(-1)+2/1000(1999), which you'll choose over 997/1000(-2)+3/1000(1998) etc. until you've chosen a guaranteed 1 util over 0/1000(-999)+1000/1000(1000), at the guaranteed cost of 999 utils. This example supposes you keep taking the offer regardless of how the payout structure correlates with past offers, but it basically works for large numbers of independent offers by LLN. So you have a paradox- at what point do you stop taking the offers? for examples like yours it would take too many instances for this to ever be a practical problem, and I think that's where intuition starts to go astray.

I think most people think of probabilities in terms of how things will average out in the long run- hence the usefulness of 'imagine 100 people and 20 of them are dead' kind of visualisations. So when there's no run long enough for probabilities to average out, our intuitions don't work anymore. Even when we're making a decision about our own lives it ceases to feel like a tangible thing and just feels like manipulating numbers.

0 notes

Text

Suppose I was offered a chance to take the lottery A with this ε. Would I do it?

See, I wouldn't either, because I'm not a perfect altruist. I think taking lottery A would be the right thing to do, and I would have great respect for anyone who did, but I need my right arm for umm reasons. This is basically what people volunteering in e.g. with the allies in WW2 did: them individually volunteering has a tiny chance of being pivotal, and comes at great personal cost, but the benefits still outweigh the costs because of how important it is to win.

If the good thing is something that happens entirely to me, then I would take that lottery- or maybe I'd chicken out, but I'd be irrationally making myself worse off if I did.

I think the counterintuitiveness here comes because this involves large numbers and probability, meaning most people will reason about it in a flawed way- and in practice people often don't act in accordance with the Von Neumann Morgenstern axioms, even when they explicitly intend to- and also perhaps because human psychology is such that there just isn't any pleasure that great which we can imagine.

Perhaps this is why when we scale down the stakes to more imaginable scales it seems more reasonable: E.g. looking both ways on a country road when you can't hear a vehicle coming is very unlikely to make any difference- it is almost certainly just wasting a few seconds of your day- but in the unlikely event that it does make a difference it makes such a big difference that we find it worth our while to enter this lottery we are almost guaranteed to lose.

@gamingavickreyauction Oh, right, here's one trouble I have with expected value maximization:

Say there's a lottery A, and in this lottery I have a 1 - ε chance of getting my right arm ripped off and going blind. This is pretty bad. Say it has utility to me N, where N is a negative number of large magnitude. There is also an ε chance of something really really good happening, something extravagantly good like world peace and I live forever and get everything I want. Let's say the utility of this outcome to me is M. So the expected value of playing this lottery is E(A) = N(1 - ε) + Mε.

Now, N is pretty big, but it's still finite. Getting my right arm ripped off and going blind would pretty thoroughly fuck up my life in every way that I care about. So I really don't want that. But it's not the Christian hell, it's not infinitely bad. Fix ε to be some very small number 0.00000000000001 or whatever. With N and ε fixed, we can always choose some M such that E(A) is greater than zero. In fact, we can choose M so large that E(A) dominates the expected utility of my entire life.

Suppose I was offered a chance to take the lottery A with this ε. Would I do it? I strongly suspect that I would not, no matter how big you make M. You can chalk this up to a failure of reasoning on my part, a failure to truly internalize the bigness of M. But it feels to me like, no matter how big you make M, participating in the lottery would basically just be signing up to get my arm ripped off and go blind. Like that's just definitely what would happen, I would totally not get M. The expected value is a mathematical abstraction, and I'm not signing up to more-or-less certainly get dismembered over an abstraction. I think I would not accept this lottery! And I think probably most people wouldn't.

I believe this goes against one of the Von Neumann–Morgenstern axioms.

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

In defence of argument 1:

In my understanding, the word "consequentialism" means you have a function f: S -> X from states of the world to some linearly ordered set X. We'll assume X is the real numbers, because it would be pretty weird if it wasn't. Then the action you should take is the action that maximizes f(s). However, in reality, we don't know what effect our actions will have. Maybe that baby you saved will grow up to be turbo-Hitler. So we generally instead maximize the expected value of f(s). This move, or something like it, isn't really optional for consequentialists, because just about every practical problem is uncertain.

So does this approach fall foul of the stoolmakers? Assuming a utility of 1 if we get a stool and 0 otherwise, it needn't be the case that the expected benefit of each stoolmaker participating adds to 1. In fact, if each assumes all the others will definitely participate, each will conclude there is an expected benefit of 1 from their labour. So taking the expected utility of a vote isn't assuming additivity in a problematic way: we are adding up f(s), not adding up s.

So what is the expected benefit of voting? It's the expected benefit of the least bad option winning over the worst bad option winning per person, multiplied by the number of people, divided by the probability that your vote was pivotal. E(B) = bNp. Now, in a larger voting population, the probability of your vote being pivotal will be smaller, approximately inversely proportional to the number of people, so the large and small terms cancel out. The benefit of voting, in this analysis, is on the order of b.

But the sum of E(B) for each person needn't add to bN, so this isn't additive. In an election in a safe seat, for example, p will be far lower than 1/N. This suggests, for example, that the expected value of voting is much smaller in New York than in Wisconsin, for example, as your vote is much more likely to be pivotal if it's expected to be a close election.

Take a numerical example: lets say there are N people other than you (N is large), each with a 1/2 chance of voting for each option. This is a very close election. Then p is the probability of exactly N/2 votes being cast for your party. The number of votes for your party follows Bin(2N,1/2), so this is N choose N/2 *2^-N. Using Stirling's approximation this is 1/sqrt(Npi). And this is what everyone sees as the probability of their vote being pivotal. So it adds to more than 1- it isn't proportional to 1/N- and the bigger the election, the more important it is to vote, because the consequences scale up faster than the volitility scales down. I think this is counterintuitive because it is an unrealistically extreme example of a close election, but it illustrates that the expected utility argument isn't based on an assumption of additivity.

This agrees with my intuitions about when voting is valuable, and I think it agrees with most people's intuitions. Notably, if it could be known with certainty that your candidate was going to win anyway, or that your candidate was going to lose, the benefit of voting would also be 0. This special case resembles the Maxist analysis.

Now, it's not necessary to use the expected value, specifically, and Max has indicated in the past that they are critical of expected utility, though I don't think they ever laid out why. So there's a more general approach to rescue consequentialism from uncertainty:

A lottery assigns a probability of various events in S, so if S = {win the election, lose the election}, a lottery could be winning the election with probability 0.23 and losing with probability 0.77. We only need a function F: L(S) -> X that assigns lotteries over S to values in an ordered set, which we will assume is the real numbers, where the bigger F(l) the better.

We can make new lotteries by combining two lotteries, say l3 = p l1 + (1-p) l2. Suppose someone flips a coin, and if it lands heads, they give us lottery l; if it lands tails, they give us lottery n. This would be a new lottery, 1/2 l + 1/2 n. Presumably if we prefer lottery l to lottery m, we should also prefer flipping a coin and getting l on heads to flipping a coin and getting m on heads- otherwise our preference would depend on whether they flipped the coin before or after they asked what our preference is. So F should satisfy F(p l + (1-p) n) > F(p m + (1-p) n) if and only if F(l) > F(m). But other than that we have a lot of options other than the expected value, right? It turns out no, even with these minimal axioms, F must have the form of E(f(s)), or g(E(f(s))) for some strictly increasing g, and f some function S -> R. This is a variation on the Von Neumann Morgenstern theorem.

I've said this before but: as a strict consequentialist about ethics, I don't believe that voting matters because one's vote is almost sure to be inconsequential. This is not related to an larger sociopolitical convictions of mine, it's purely mathematical. People are already happy to acknowledge that (in the US, say) if you live in a state that always goes blue or always goes red, your vote doesn't actually have any effect. But this is true everywhere (except very small elections), it's just most obvious in these states.

Now, telling people to vote might well have an effect. If you have a large platform, and you say "go vote for candidate X!" and 1000 people do it, that might be enough to actually affect the outcome of an election. So I get why voting discourse is the way it is; advocating for others to vote is a very cheap action that might have a large effect size, so lots of people are going to do it. Turns out it can be rational to advocate for something that it is not in fact rational to do. This is pretty obvious if you think about it but for some reason people really don't like this idea.

Anyway, even though people know that their vote is not going to change the outcome of an election, they usually make one of two arguments that voting is rational, and these arguments are both bad.

The first is "if 1000 votes can have an effect, then one single vote must have 1/1000th of that effect, which is small but not zero!" or something like that. This follows from the false belief that effects are additive; i.e. that the effect of two actions is just the effect of one action "plus" the effect of the other. This is sort of patently nonsense because it's not clear what it means to "add effects" in the general case, but that's mostly a nitpick (people know roughly what they mean by "adding effects"). More important is that it's just wrong, and can be seen to be wrong by a variety of counterexamples. Like, to make up something really contrived just to illustrate the point: suppose you want to sit down on a stool. And there are no stools in town, but there are four stool-makers: three who make legs and one who makes seats. And none of them can build the stool on their own, each is only willing to make one part per stool. Maybe it's some sort of agreement to keep them all in business. Anyway, let's say you commission a stool, but the seat guy doesn't show, so you just end up with three stool legs. Does this allow you to "3/4ths take a seat"? Can you "take 3/4ths of a seat on this stool"? No, you can take zero seats on this stool, it's an incomplete stool. Effects are not additive! 1000 votes might sway an election, but that does not mean that any individual vote did so, and in particular if any one of those 1000 people chose not to vote it is very likely the election would have gone the same way!

The second bad argument goes like "if everyone thought like you, nobody would vote, and that would be bad!". This also fails in a simple logical way and a deeper conceptual way. The logical failure is just that the antecedent of this conditional is not true, not everyone thinks like me. And in fact, my choice to vote or not in itself has no impact on whether others think like me. Thus "if everyone else thought like that it would be bad" might be true but is irrelevant, you can't conclude anything about whether I should vote or not from it. Conceptually, I think this arises from this sort of fallacious conception of oneself not as a particular individual but as a kind of abstract "average person". If I don't vote, and I'm the average person, that basically means the average person doesn't vote! Which would be bad! But of course you are not the "average person", you are you specifically. And you cannot control the average person's vote in any way. Instead, the blunt physical reality is that you have a small list of options in front of you: vote for candidate 1, vote for candidate 2, ..., vote for candidate n, and I'm sure you can agree that in actual reality no matter which one you pick the outcome of the election is not likely to be changed. Your vote doesn't matter!

Now, I should say at the end here that I do in fact vote. I vote because I have a sort of dorky civics enthusiast nature, and I find researching the candidates and voting in elections fun and edifying. I vote for my own purposes! But I don't believe that it affects the outcome of things, which it plainly mathematically does not. I have no further opinions on voting discourse.

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

You're speaking about feminism as if what it does is unified, and that works for organisations, kind of, but not for movements. When anyone can walk under your banner there are going to be all sorts of stupid things happening under your banner, so by your standards we'd have to reject every political movement. Instead, we should judge movements by their best parts, and the parts that will actually stand the test of time.

When someone says they don't like PETA, there are multiple reasons why they might say that.

They are against the ethical treatment of animals

They are for the ethical treatment of animals, but they believe that PETA does not do a good job of achieving that

They have a nuanced position on what it means to treat animals ethically that disagrees with PETA's position

They don't care about the ethical treatment of animals but they hate being inconvenienced

etc, etc...

Just based on the fact that someone disagrees with a group that calls itself "for the ethical treatment of animals", we cannot distinguish their actual position on the ethical treatment of animals.

This is about feminism, but it's also about every ideological movement ever.

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

It irks me when people defend feminism and all they talk about is legal rights, because that, in developed countries, plays into the idea that 'feminism is over.' Even in 'progressive' countries there is so much left to do, and which feminists are pushing for.

Discrimination isn't just about legal rights, it's about the triple shift and women doing more housework in straight couples where both work full time. It's about the pay gap and the fact that women tend to work in different industries than men—because this is an expression of socialization, not just natural differences between male and female brains. It's about sexual harassment in the workplace, in schools, everywhere. It's about the lack of shelters for people fleeing abuse, the number of people forced to stay with abusive partners for financial reasons, and the fact that the legal system is still so hostile to women reporting domestic abuse or sexual assault. It's about prevalent everyday sexism, and beauty standards that women are judged for not adhering to. It's about how talking about periods is stigmatized, and endometriosis and PCOS are so often missed. It's about the disproportionate impact that having children has on women's careers.

Some of these issues affect men too, but they are undeniably gendered. And I think protecting men from domestic abuse is also a feminist goal.

1 note

·

View note

Text

i do feel a bit weaselly when people assert "Well you should take on this commitment because it's an xist [where x is some ideology (just like the last post)] commitment" or asks "Are you an xist?" in part because I'm cautious about the rhetorical and inferential role that "I am an xist" or "This idea is a feature of x" plays. And I think I also tend to be moreover a little ambivalent about what labels to adopt. By way of example, I will freely steal from liberal principles, forms of argument, etc., but then turn around and criticize the liberal form of life, liberal neutrality, and so on. I could be described as a liberal perhaps. I could be also described a sympathetic critic of liberalism. I don't think much really rests on which side I fall on. And I think I often see people who are really hardcore about giving a thoroughgoing xist account of the world tend to have rather large gaps in their hermeneutical resources and seem forced to just wave away too much testimony, too much data, too many experiences, and too much of the other miscellany that forms the basic fiber of our world construction. And I suppose it produces a kind of formulaic way of thinking about the day's crowned discourse that I have sort of (ironically enough) programmatic reasons for being resistant to. I think a bit of eclecticism is good in that it's a little less gappy, requires a bit less waving away and so on. The trouble is of course going to be organizing everything into a coherent picture and seeking the higher orders of explanation. But I think that's an iterative process that we just don't stop doing (or shouldn't stop doing rather) throughout our lives. We put too many stops on this process of constant creative reimagining. I suppose, to a certain extent, this is just kind of a Romantic view about political epistemology but I think it's worth taking seriously.

#I think of ideologies as lenses then I try to collect them all because what is a lens but a sparkly rock?#this approach requires good epistemic hygiene though and must be done in moderation

81 notes

·

View notes