Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Photo

CRISPR’s Adaptation to Genome Editing Earns Chemistry Nobel

By Amanda Heidt (The-Scientist). Images: © NOBEL MEDIA 2020 ILLUSTRATION: Niklas Elmehed and Johan Jarnestad/The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences.

This year’s Nobel Prize in Chemistry has been awarded jointly to Emmanuelle Charpentier of the Max Planck Institute for Infection Biology and Jennifer Doudna of the University of California, Berkeley, the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences announced on October 7th. They are recognized for their pioneering work in developing CRISPR technology, which has revolutionized the field of gene editing.

“Today’s Nobel Prize in Chemistry recognizes CRISPR-Cas9, a super-selective and precise gene-editing tool where chemistry plays an incredibly important role,” Luis Echegoyen, the president of the American Chemical Society, of which Doudna is a member, says in a statement. “This discovery, originally derived from a natural defense mechanism in bacteria against viruses, will have untold applications in treating and curing genetic diseases and fighting cancer, as well as impacts on agricultural and other areas. The future for this technique is indeed bright and promising.”

“I don’t know quite what to say. I’m about as shocked as I’ve ever been,” Doudna tells The Scientist, reacting to the news of her award. “I’m really so grateful.”

CRISPR-based technology allows scientists to precisely manipulate DNA, a desirable ability for many fields. CRISPR has contributed to discoveries across disciplines, conferring mold and pest resistance to important crops, leading to new cancer therapies, and, more recently, repairing damage within mitochondrial DNA. During the COVID-19 pandemic, CRISPR has also been used in new diagnostic tools for detecting the virus.

“This type of research will always lead potentially to a way to discover new pathways that could be useful for developing therapeutics against bacteria,” Charpentier said during a call with the Nobel Prize committee, “but also as a way to find new mechanisms to target genes and their expression.”

A CRISPR CUT: The guide RNA (gRNA) forms a complex with Cas and directs the enzyme to cleave the target DNA to which the gRNA binds through complementary sequence. The cell tries to repair the DNA break, which often results in the insertion (as shown) or deletion of nucleotides that changes the reading frame of the gene and a creates premature stop codon. THE SCIENTIST STAFF.

Charpentier completed both her PhD and her first postdoc in the lab of Patrice Courvalin, a microbiologist at the Pasteur Institute in Paris. “She’s a very obstinate scientist. She will not quit the problem, and will work on it until the end,” Courvalin tells The Scientist. “Science is all her life.”

Through her study of the bacteria Streptococcus pyogenes, Charpentier discovered a new immune molecule, called tracrRNA, that neutralized viruses by breaking apart their DNA. After publishing her findings in 2011 in Nature, she initiated a collaboration with Doudna in which the pair isolated and refined the molecular underpinnings of these genetic scissors.

Their landmark paper, published in Science in 2012, tracked closely with work being undertaken by other researchers at the time. Virginijus Šikšnys, a biochemist at Vilnius University in Lithuania, published a paper in PNAS in September that year in which he and his team further characterized the bacteria’s immune mechanism. While Charpentier and Doudna’s paper published first, in June, it was submitted later. Their results reaffirmed earlier findings that CRISPR could be used to cut double-stranded DNA at specific, predetermined sites along the genome, and further simplified the tool by showing that crRNA and tracrRNA could be fused to create a single, synthetic guide to direct the cutting mechanism to a site of interest. The next year, in 2013, Doudna’s team applied her new technology to human cells.

The adoption of CRISPR and the subsequent iterations that endowed the tool with new abilities have been global. At the same time, there have been ongoing disputes over the ownership of the intellectual property. The first patent for the use of CRISPR gene editing technology in eukaryotes was granted to the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, based on the work of Feng Zhang’s group, back in April 2014. While the University of California has sought to have its own patents, based on Charpentier and Doudna’s work, take precedence, in February 2017, the US Patent Trial and Appeal Board sided with the Broad—a decision later upheld by US Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit. The battle is far from over in the US, and another patent battle rages in Europe, where the European Patent Office has already revoked at least one Broad patent.

Charpentier and Doudna join 53 women who have previously won a Nobel Prize, including only five who have been awarded in chemistry. The last prize in chemistry went to Frances Arnold in 2018. “It’s stunning, it’s appropriate, and it brings joy to those of us who are women in science,” Lila Gierasch, the editor in chief of the Journal of Biological Chemistry, tells The Scientist.

The pair will share the prize of 10 million Swedish kronor, or about $1.12 million.

334 notes

·

View notes

Text

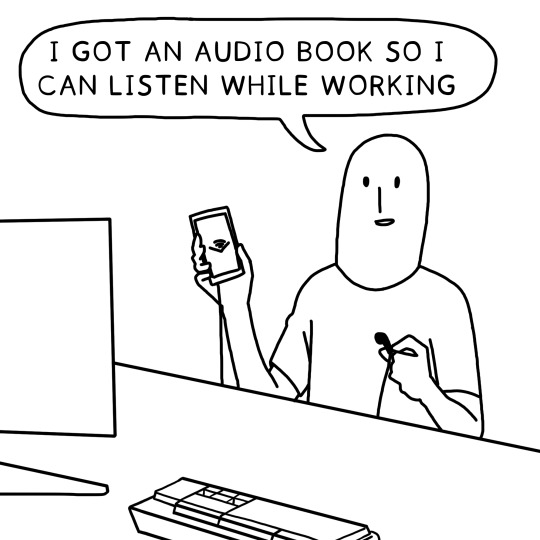

Source: https://twitter.com/denis__draws/status/1302125514031878145?s=19

2K notes

·

View notes

Note

Do you know any cursed pumpkin facts?. I love pumpkins

growing Giant Pumpkins is an intense and highly competitive practice as growers produce larger and larger pumpkins every year and enter them in various competitions.

the largest pumpkins currently top a ton in weight, and seeds from these prize-winning goliaths can sell for hundreds of dollars apiece proving there is indeed such a thing as a Pedigree Pumpkin.

49K notes

·

View notes

Photo

A Love Letter To Iceland Hungary-based photographer Gabor Nagy shares his love letter to Iceland.

“Dear Iceland, you know how much I love you. You gave me so much in the last 5 years. A reason to believe, a new passion and new friendships. Every summer I just waited to touchdown in Keflavík to finally admire your natural beauty again. And you’ve never disappointed me. Ever. Now it’s summer again and I already miss you like never before, but this year I don’t think I will be able to meet you for obvious reasons. The only thing I can do is to scroll through my catalogs and share the most memorable moments you offered me. “

10K notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

T: “...milion little kisses...”

0 notes

Note

Why were animals so giant in prehistoric times?

animals tend to evolve towards gigantism over long periods of time, so at any given point in earth’s history when tetrapods had shown up and the climate had been stable for a while, you absolutely find giant animals.

and remember, animals were actually still pretty giant until fairly recently on the geologic scale, a mere ten thousand years ago!

the reason there are very few giant animals around now is that we’re actually living in a post-apocolyptic world.

SOMETHING happened ten thousand years ago to wipe almost all of the ice-age megafauna off the planet, and we’re still not sure what. (and no, it wasn’t us.) but the first animals to fall in a mass extinction events are always the giants, because they require so much food! and it takes them tens of millions of years to show up again after a mass die-off. but give it another twenty million years or so, and giant animals will appear once again!

until then, please take a moment to appreciate whales.

9K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Sullivan and Houston in the snow, 1982

288 notes

·

View notes

Photo

If this year has taught us anything, it’s that we all had an illusion of control over our lives and the world. Peace for me comes when I have let go of that illusion instead of trying to grip onto it so tightly -photographer Chris Burkard

234 notes

·

View notes

Text

Branching Light with Soap Bubbles

By shining laser light through soap bubbles, researchers have demonstrated branching flow in light for the first time. (Video credit: Nature; research credit: A. Patsyk et al.; submitted by Kam-Yung Soh) Read the full article

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

"Vorticity 3"

Mike Olbinski’s “Vorticity 3” is a stunning view of storm chasing in the American West. (Video and image credit: M. Olbinski) Read the full article

598 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Look there- look at that sign. They don't- they can't tell me what to do!"

[various background laughter]

8K notes

·

View notes