Photo

THERE WILL BE BLOOD || Aesthetics

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Recalibrating Dreams: Gerwig Leads, Lower-Middle Class Anxieties and Other Informed Behaviors in Lady Bird

Portraying the anxieties of the lower-middle class, working people who live paycheck to paycheck, has been an increasingly rare exploration in American film and television. There was once a period of portraying more blue-collar and lower-middle class Americans for mainstream audiences with sitcoms, from Norman Lear’s socially conscious portrayal of the decline of the post-war American nuclear family (Good Times, One Day at A Time, Maude) in the 1970s to The Carsey-Werner Company sitcoms in the 1980s through the 1990s (Roseanne and Grace Under Fire). These shows were broad comedies with bite, on occasion stepping into dark terrain by never losing sight of their characters’ economic realities. You saw and heard discussions about finances by characters at the dinner table, characters get laid off, and characters move into different service industry jobs and trades not because it made for a more fruitful comic situation, but because the character had a mortgage to pay. Nobody would confuse these shows with the works of an Alan Clarke, Ken Loach, or Mike Leigh film as far as serving realism, but they picked up the slack for Hollywood television and films that used their mediums differently, eschewing any discussions or observations their characters’ socio-economic situation.

Hollywood can never quite shake off what it serves best: as entertainment and aspirations for viewers, despite the latter not necessarily having to be innate of the former. American independent film will always have the issue of availability and limitations in reaching an audience on a film about class, even if some of the strongest American independent filmmakers (Charles Burnett or John Sayles as notable examples) having a “mainstream” moment in the sun. But as the American middle class has dwindled, so has a more realistic representation of being middle-class and the actions and decisions entailed toward maintaining (and not so much moving up) that class status. Enter Greta Gerwig’s Lady Bird, which may be one of the most finely observed films about lower-middle class economic anxiety in a mainstream American film that I have seen in some time.

Gerwig’s most notable non-acting contributions prior to Lady Bird have been as a writer for the films Mistress America (2015) and Frances Ha (2012), films illustrating quarter-life crises and ennui in a madcap, screwball manner. In those films, despite the characters Brooke and Frances (both of whom portrayed by Gerwig on screen) being older than eighteen year-old Lady Bird, they have a similarly fleeting id that is often undercut by reality. When you see Frances Halladay run around the New York City night looking for an ATM machine to save face for to pay a dinner bill on a date, her pause when considering if she should pay the additional charge fee to get money from her pretty paltry bank account balance does hit the audience as much as it hits her. Gerwig’s dramatic stakes in her scripts are whether the mistakes and repeated mistakes by these characters mount into something that they can’t easily walk away from. Brooke in Mistress America loses funding for her restaurant due to cheating on her boyfriend and her dreams are met with people who are willing to just give her basic financial help, but on the condition that she get her head out of the clouds. Brooke does get her debts covered and considers applying for college than continue to on a free spirit life. Frances leaves and returns back to New York in a more realistic and financially stable apartment and job situation. These films and character trajectories are not so much morality tales. You can feel the wincing in the writing and the filmmaking as you see these characters make a decision that could end- and usually does- badly. That wincing is not because of judgment, but wincing out of familiarity. Gerwig’s characters are in certain degrees of an arrested development (a notable line in Frances Ha, has Frances apologize by saying, “I’m so embarrassed. I’m not a real person yet.”), operating like cars running on empty. Yet, these characters are also resourceful and have a certain hustle to them. So where did these characters come from and who made it possible for them to be where they were in the first place? In a way, Lady Bird could be seen as a prequel for those characters but that would be reductive in saying Gerwig makes only one type of character and movie. It is about seeing your hometown and surroundings as the default and the most realistic option, but it is also a place where your dreams are formed.

Greta Gerwig’s Lady Bird begins with a quote from Joan Didion (from a 1979 New York Times feature on Didion), “Anybody who talks about California hedonism has never spent a Christmas in Sacramento.” It is the film’s setting and also the hometown of Gerwig and Didion. In that same New York Times piece, Didion’s relationship with Sacramento, the California state capital, is expounded upon. Didion holds her place origin with reflective love, something that Lady Bird is told she similarly does, unconsciously, when writing about Sacramento.

Another key Didion quote as far as her relationship with California is in Slouching Towards Bethlehem, “All that is constant about the California of my childhood is the rate at which it disappears. California is a place in which a boom mentality and a sense of Chekhovian loss meet in uneasy suspension.” While Didion’s writing represents for a lot of people, observations of a California synonymous with late 1960s counter-culture, Didion grew up in Sacramento during the Depression-era 1930s to World War II 1940s, before moving around due to her father’s job with the US Army Air Corps. In that time, the preeminent writer of record for the Golden State was John Steinbeck. As viewers, we know that Lady Bird knows John Steinbeck, as we get a scene Lady Bird and her mother Marion crying in the car as they finish up listening to an audiobook of Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath. The Grapes of Wrath is about the Joad family, led by ex-con Tom, who escaped to California from the Dust Bowl in Oklahoma. California was often the place for people to escape to from our parts of the country, often romanticized as a place of opportunity and rebirth. The Joads uprooted to California more out of physical displacement, representing the Okie diaspora, but the ‘Go West’ attitudes and Route 66 pushed their momentum in that direction. To borrow from Didion, the Joads were boom mentality mixed with Chekhovian tragedy, the book notoriously ending with the Joads, down on their luck again despite reaching California, taking pity on a dying stranger and his young son in a farmhouse, an ending is dark and anti-climactic all at once. Steinbeck was highlighting the dark reality that the Great Depression was everywhere but humanity and kindness were still intact for the Joads. Steinbeck eschews the valor in that, it just how it is, be it faith or survivalist instincts or pragmatism.

But if California was- and remains- the destination of aspiration, dreams, and another life, what of the Californians who look to the other side of the country for refuge? Teenage Lady Bird McPherson is not leaving Sacramento due to some cataclysmic ecological event, she just wants to go to college and leave her hometown. In conversation with Francis Ford Coppola in Interview Magazine, Gerwig summarized the yearning to go to a faraway place because it offers more than your current station being something inherent to that age and, arguably, growing up from the realization that it is not tangible. She states, “I think when you’re a teenager, you always feel as if life is happening somewhere else—it certainly isn’t happening to you. And then you get to the place where you think your life is supposed to be, and you look around and realize it doesn’t exist.” Lady Bird’s ending is hardly dark as The Grapes of Wrath but the film contains a lingering economic-based anxiety that Gerwig incorporates in the foreground, background, and fringes of the frame. It lingers and is omniscient, mundane even but that is because it is the normal.

Lady Bird follows its lead character and her family through her senior year at her parochial school Immaculate Heart in Sacramento, California. Viewers are notified immediately about the situation with the McPherson home. Lady Bird’s older brother Miguel and his girlfriend Shelly, both Berkeley grads, have trouble finding work despite going to one of the best universities in the country, settling on working as grocery store clerks and living under Miguel’s parents’ roof. Lady Bird’s father, Larry, is quiet and reserved, but hardly stoic in what is going on with him personally and professionally. He knows layoffs are happening at work and is resigned to the fact it will (and does) happen to him. He takes pills to deal with depression but this fact about him is a discovery for Lady Bird when it catches her eye in the medicine cabinet. He tries to apply for jobs, but at his age he feels out of place being interviewed for positions by people half his age. Still, Larry is engaging and a peacemaker for the most volatile relationship in the film: Lady Bird and Marion.

Marion is a nurse at a psychiatric hospital, often working random hours and doing double shifts to try to balance the family’s tightening budget with Larry getting laid off. Scenes of her and Larry with pencils, pens, paper, and a calculator breaking down their what will it take for them to keep up on their bills recur throughout the film. We see her carefully look at bills and receipts; such as her surprise that the grocery bill is still as high as it is despite her son Miguel’s employee discount. Marion can best be characterized as all work and no play, a notable scene of her on her feet in the kitchen while the rest of the family unit are sat down at the table before they (with the exception of Larry all disperse) that is notable because there is clearly not enough chairs at that table and of course, Marion is the one who offers her spot to an already pretty tight dinner table. The McPherson home is modest, one full bathroom for five people under one roof, and scenes of Marion’s fights with Lady Bird feel even more oppressive and combative due to the size of space and general lack of privacy. Due to the family’s financial downturn, Christmas feels smaller due to quantity and quality; Marion trying to keep on her best face as she gives her children socks. The family follows her cues. Marion airs out a lot of lamentations and feelings of disappointment, that she can only keep her head above water, that she thought their residence would just be a starter home for a subsequent bigger place that never came to be, and the constant insecurity that her daughter either is not applying herself with the opportunities afforded to her or that Lady Bird is ashamed of the McPherson’s financial status. When Lady Bird tells Marion to stop hovering over her life like a hawk, Marion dryly reveals to viewers (and possibly Lady Bird herself) that her mother was an abusive alcoholic and leaves Lady Bird’s bedroom. The prickly nature, nurturing love, and insecurities in whether she is doing anything right because Marion was without guidance and an ideal upbringing that caused her to create an armor around her. She is doing the best she can, simultaneously playing the role of bad cop in voicing her consternation in her daughter’s youthful ignorance and questioning her achievements in mothering.

We see the twinning often of Lady Bird and her mother, in how both deal with two different characters disclosing and divulging to them deeply personal information, that they both are whom people turn to in a time of need. Then there is the fact that both have a hobby of looking at the upper-class homes, Marion and Lady Bird going to open houses, Lady Bird and her friend Julie walking through the Fabulous Forties neighborhood in Sacramento. Marion cracks to Lady Bird that reading magazines in your bedroom is what rich people do, but she too indulges outside of her class, albeit in a window-shopping, browsing way.

Lady Bird’s own dealings with her class vary throughout the film. We see her get dresses at the marked down Thrift Town store, not once remarking on the clothes not being from a major brand- perhaps she got that insecurity out of her system a long time ago. We see her throw away her parents lunches and have her father drop her off a block away, that has become so unconscious for her that it takes a calling out by people on how bad the optics are for her to treat her father and mother that way. There could be a whole film built on the whole ruse of her pretending that she is from the Fabulous Forties neighborhood to the cooler kids of Immaculate Heart and Xavier. But that plot line ends almost as quickly as it begins, getting exposed by Jenna, who never calls attention to finding out Lady Bird being poorer than she originally claimed. She gets into discussions and debates about money with her mother, ‘Money is not life’s report card’ being a line that sticks out, something that Marion has likely said to herself numerous times. We see Lady Bird being resourceful in ways that surprise both her parents, taking on two jobs by the end of the film, her college financial aid applications were paid with her own money from her summer job savings, always aware that she has scholarships on the line with Immaculate Heart, and being in the room when her father goes to the bank to re-finance the family home in order to pay for Lady Bird’s college tuition. It is not a, ‘pull yourself up by your bootstraps’ mantra for Lady Bird, as her through-line over the course of the movie is her going from wanting boots to getting the boots to even begin to really walk toward potential opportunity.

And the movie notes that some people do not even get to really have the boots. Class anxiety is not limited to the McPhersons. Lady Bird’s best friend, Julie, is in a single parent home. Briefly, we see her enjoy the bliss of having her mother’s boyfriend dropping her off her to school in a sports car and getting freshly made lunches made by that boyfriend (that she lets Lady Bird also reap the benefits a brown bagged sandwich) until her mother breaks up with the boyfriend- something that Julie had kept tabs on, to milk whatever feeling of luxury she can get before the relationship ended. Julie, although never lying to the degree Lady Bird does, does conceal her economic reality as best she can. The viewer only finds out about Julie living in an apartment complex because Lady Bird goes there to see her. Still, there were some clues Gerwig dropped about the character, such as Julie stating she wished she lived in a Fabulous Forties home because it would mean she would finally have her own bathroom. When Lady Bird moves toward hanging out with Jenna and Kyle, the richer kids, while Lady Bird may not have considered how it would come across, Julie had to have felt like she could not offer her best friend the same luxury and status of being like those two. Julie is a good kid, one of the brightest students at Immaculate Heart and gets to be the lead in the musical. But she has to go to Sacramento City College, a community college. She tells Lady Bird that she will spend the summer reconnecting with her absent father and you wonder what that will involve. Will Julie try to see if he will be open to financial support that she might need to not just go to community college? Likely not. Julie is living within the most realistic and pragmatic confines of her life. “Some people aren’t built happy,” she cries, which could relate to several things, including her financial status.

Lady Bird ends at a new starting point for its lead character. Lady Bird returns to going by her given name, Christine, although cannot quite embrace being from Sacramento (stating to a hookup that she’s from San Francisco). Watching all of the steps and sacrifices that she and others made for her to get to college in New York City and suddenly her impulses and mistakes, that already carried weight (and made me wince), get heavier. Christine cannot afford to mess up, in both a figurative and monetary sense. She knows that back home her parents love her but also would remark on every choice and direction she goes, be it a potential mistake or opportunity. Christine has not moved up in class, her socio-economic standing has informed her and she cannot run away from where she came from. She has to compromise being the free spirit, messy, creative person and holding tight her responsibilities in achieving her dreams. Will she succeed? Lady Bird presents how dreamers that feel outsized from their surroundings still carry responsibilities and anxieties with them. The precision to reach goals become imperative and those goals themselves may well be informed by the pragmatic realities that led them to where they are. And it is important not to lose their grip on that.

162 notes

·

View notes

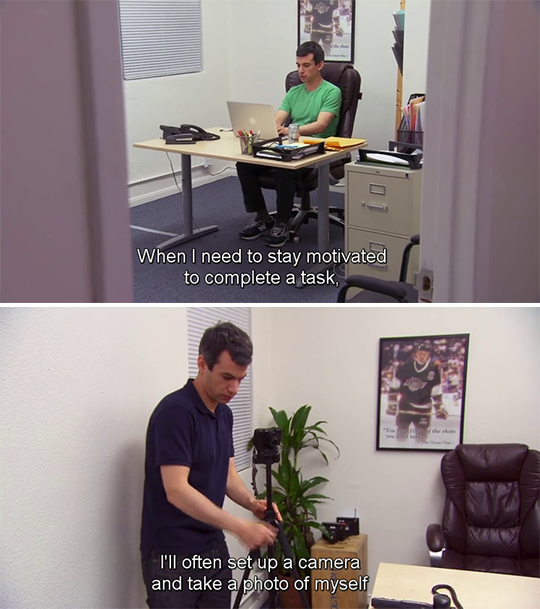

Photo

21K notes

·

View notes

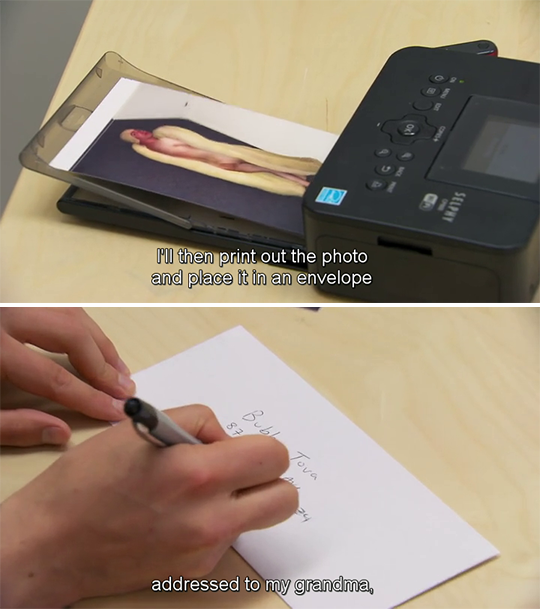

Photo

stages of being

210 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ryan Gosling and Denis Villeneuve photographed by Christina House for LA Times

141 notes

·

View notes

Video

undefined

tumblr

Need the sound for this

87K notes

·

View notes

Photo

I trust that my followers will make the right decision

2K notes

·

View notes

Photo

“What do you see?”

“Home.”

Dunkirk (2017), dir. by Christopher Nolan.

659 notes

·

View notes

Photo

No, wait! It’s me… Hogarth. Remember? It’s bad to kill. Guns kill. And you don’t have to be a gun. You are what you choose to be. You choose.

1K notes

·

View notes