An alliance of groups and individuals led by Russel Honoré fighting for clean air, clean water, and healthy communities in Louisiana.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

“Clean water is our lifeblood”

Chapter 9 of Don’t Get Stuck On Stupid!, a book by Lt. Gen. Russel Honore’ (U.S. Army-Retired)

“Two things are infinite: the universe and human stupidity. And I’m not sure about the universe.” – Albert Einstein

The next major international wars will be fought for water.

For the past few decades, the biggest threat to global security has been competition for oil. But now it’s about water.

In fact, it’s already happening. There’s been a sustained drought in parts of Africa and the Middle East for many years, and this has put a strain on governments to find new sources of water.

Some analysts claim the Syrian war, which began in 2011, was started over competition for water. In the Middle East, nations like Israel, Jordan and their neighbors are always in conflict over who controls the water.

Water has become a commercial commodity that in many respects is more valuable than oil. Consider that about 60 percent of the human body is water, and that clean drinking water is our lifeblood. We also use massive amounts of water to produce the food we need in order to survive.

Oil, on the other hand, is somewhat of a luxury, and we’re finding ways to replace it.

Since the 19th century, water has evolved from being a public commodity to a private enterprise. However, it may be difficult to realize that water – like oil – has become “monetized,” because it seems like water is everywhere. We’re surrounded by it; we take it for granted.

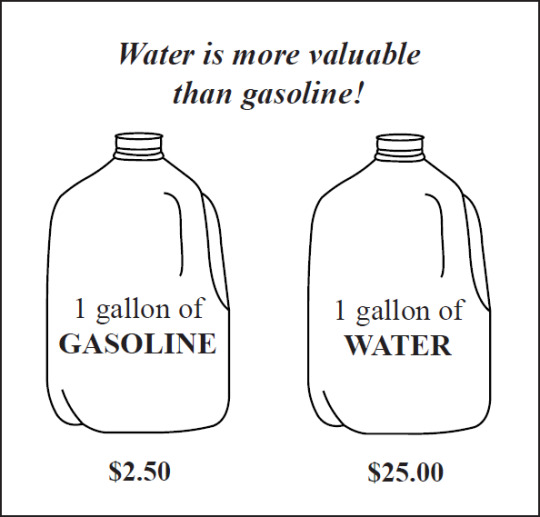

Nonetheless, we can pay more for water than we do for gasoline. A gallon of gasoline costs $2 to $3. At the airport, a 20-ounce bottle of water costs $4 – which works out to about $25 a gallon. And it comes from places like Fiji or Iceland.

Why in the hell are we importing water from Fiji? That’s a drought-stricken country run by a dysfunctional military regime and where the citizens struggle to find clean drinking water. Why? $25 a gallon, that’s why! It’s more valuable than oil. There’s money to be made with water.

Clean drinking water is a human right

Consider that there is less clean water in the world today than there was yesterday, and there will be even less tomorrow. The reason is the growing global population and the strain this puts on all resources.

Between 1997 and 2017, we grew from about 5.8 billion people to 7.5 billion people, and the growing population keeps dirtying the water but not cleaning it. The speculation is that the world will grow to 10 billion people by 2067. This growth will create an even greater requirement for more clean water and more food.

Food production consumes a lot of water from an agricultural perspective, and a lot of that water gets polluted as we use it to grow those big fat pork chops and steaks, raise juicy hens, and produce ever more abundant harvests of corn, wheat, oats and other grains. Believe it or not, it takes about 660 gallons of water to produce all the ingredients in a single hamburger.

It’s widely known that the United States has less than five percent of the world’s population, though we consume 25 percent of the world’s resources. In population rankings, the U.S. is number three behind China and India – each of which has more than 1.3 billion people. Each of those two countries has a billion more people than we have.

I look at this through a military lens, and I see the threat we are facing when the world goes from 7.5 billion people to 10 billion. The expanded global population is going to require at least 33 percent more food than what we’re producing now. Moreover, in the world today, more than a billion people don’t have electricity and another 700 million don’t have clean water in their homes.

Again, we have less clean drinking water today than we had yesterday or will have tomorrow because we’re consuming it and we’re dirtying it, but we’re not cleaning it.

The three most obvious ways we’re not taking care of our water are:

We’re still allowing garbage to be dumped into our oceans.

We’re allowing our coastal aquifers to be destroyed through oil and gas production.

We’re allowing the over-use of fertilizers for agricultural production.

The explosion of the global population over the past 50 years came about partly because people gained greater access to clean water. Much of the progress in this area is due to well-thought-out initiatives by the U.S. government and organizations like the Peace Corps that work with non-governmental organizations to show people in developing nations how to clean their water and how to avoid polluting it. The adoption of better sanitation practices has also been a critical component of this progress.

We have to embrace technology to find solutions

Manufacturing and farming consumes a tremendous amount of water. We know the importance of good farming practices and the impact they continue to make on our economy and on our ability to feed ourselves and help feed the rest of the world. But we’re going to have to come up with some better solutions to the agricultural runoff.

Many of us have lived on farms, as I have, or have farmers who are relatives and friends. So I understand many of the challenges that farmers have to deal with.

At the same time, we’re still doing stupid things with farming and water – and that’s got to change.

In the early months of 2017, I was at a conference at Tulane University in New Orleans where they were looking for a solution to the “dead zone” in the Gulf of Mexico. The “dead zone” is an area of about 8,000 square miles off the Louisiana coast west of the Mississippi River delta where oxygen in the water is so depleted that the water cannot support life. This occurs from the spring through the fall.

The culprit is the nutrient-rich discharge from the Atchafalaya River and Mississippi River – in other words, excess fertilizer in the agricultural runoff from 31 states that flows into the rivers and eventually into the Gulf of Mexico. Other components of this discharge include eroded soil, animal waste and sewage.

To help find a solution to the “dead zone,” Taylor Energy Co. of New Orleans put forth a grant of

$1 million. (Ironically, one of the company’s offshore oil wells has been leaking hundreds of gallons of oil every day into the Gulf of Mexico since it was heavily damaged during Hurricane Ivan in 2004. Efforts to stem the flow have failed.)

The “dead zone” is just one example of the damage we’ve been doing to our water. And we’ve been abusing it for a long, long time – at least 50 years that I know of.

But what can we do about it? How can we reverse this trend?

First, we have to embrace technology to find solutions, and one of the most important ideas is to determine how much fertilizer the farmers really need in order to optimize the production of their crops.

What we’ve discovered is that farmers are able to reduce the amount of fertilizer they need by up to 40 percent simply by testing the soil frequently and monitoring crop growth. It’s all done based on data collected from the fields that tells the farmer he can reduce the amount of fertilizer he uses and still get the same production per acre. That’s pretty cool! The rest of that fertilizer is wasted; it’s nothing but excess that ends up in the rivers and then in the Gulf of Mexico.

We still have to address the toxic runoff from things like pig and chicken farms, but we’re getting a better understanding of how to tackle this problem.

It’s an overstatement of the obvious, but we’ve got to stop doing stupid things to our water. We’ve got to stop dirtying and poisoning it. And we’ve got to clean the water that we’re dirtying. Our very lives depend on it – seriously.

The good old days… when rivers caught on fire

Water is a complex issue, and access to navigable water and drinking water was fundamental to the drawing of boundaries between states in the early history of the United States. The Supreme Court and state supreme courts were frequently involved in settling disputes over water and water rights.

Water is often underpriced, but many of our municipalities have used water as a cash cow – meaning they will charge as much for water as they think the citizens can bear, and they don’t always use that money to re-invest in the water system. Instead, they use it to pay other bills.

The cost of clean water is rapidly increasing, and in the not-too-distant future many millions of households in the United States may not be able to afford their water bills.

The most expensive places for water in America are Atlanta and Seattle. A family of four using a typical 100 gallons of water a day pays around $326 per month for water in Atlanta and $310 in Seattle.

At the other end of the scale, the same family living in Los Angeles pays less than half of what they’d pay in Atlanta. In Phoenix, it’s one-quarter and in Las Vegas it’s one-fifth, or $64. These cities are in deserts, so they have to pipe in all their water. Does this make sense?

Even though access to water is a right, we still have to pay for it in the same way we pay for electricity and highways. Otherwise, sound maintenance of the public water systems would be close to impossible in communities where water is underpriced.

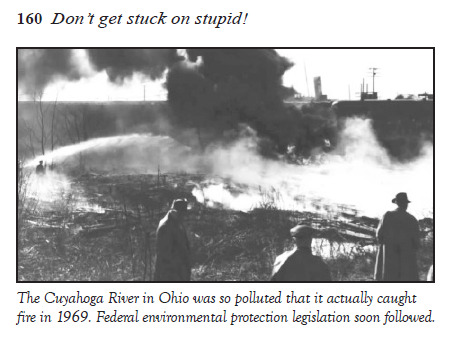

A glaring example of dirty water that really got the public’s attention is the Cuyahoga River in northeast Ohio. It was so polluted that it actually caught fire in 1969. This dramatic incident helped to spawn the environmental movement in the 1970s that gave birth to the Clean Water Act, the Safe Drinking Water Act and other regulations designed to help us clean our water.

A more modern example of not keeping our water clean and safe is what happened in Flint, Michigan.

This was a comedy of errors. First of all, General Motors in Flint and elsewhere produced cars with lead-compatible engines, which led to the Flint River being polluted with lead. The lead in the water ran through the city’s pipes for so many years that the Flint water system became a maintenance problem, to put it mildly.

The bureaucrats switched the city’s water from the Flint River to Detroit city water, but that exacerbated the problem because it dislodged the lead in the pipes. Now we have a city where the water system is full of lead and most of the population drinks only bottled or filtered water.

It’s not just Flint, though. It’s happening elsewhere as well. One of the worst water systems in the nation is in Martin County, Kentucky, a coal-mining region where dirty water is a way of life and people dare not drink it.

In Louisiana, the small community of St. Joseph has a water system that is deteriorating and the disgusting brown water is contaminated with lead and copper. People have to buy their own drinking water. It’s costing about $9 million to fix just this one system for about 500 homes. At the same time, the residents can’t afford to pay high water bills to make the system workable into the future.

Another problem city in Louisiana is Ville Platte, which is also plagued with brown, polluted drinking water. People there tell me things like, “We’re not drinking that water,” and “I’m not going to come back here and raise children with that water.”

It’s worth noting that bad water in places like St. Joseph and Ville Platte is contributing to the death of small towns.

We’ve made great progress over the years, but today it’s almost like we’ve come full circle with so many politicians and industry lobbyists whining about over-regulating industry. We didn’t over-regulate industry. We had rivers on fire and we poisoned entire cities! The air was so dirty in some cities, you couldn’t see from one side of the street to the other.

One of the first pieces of legislation signed by Donald Trump when he became President in 2017 was one repealing a regulation that stopped coal-mining companies from dumping waste and toxic coal ash into streams and rivers.

What the hell’s going on that we need to make our rivers dirtier again? Does the Trump administration really know what they are doing by telling mining companies it’s okay to let their runoff go straight into the rivers and streams? Did we learn nothing from the Cuyahoga River fire and the other disasters we’ve seen in our lifetime?

Water is big business

The competition between industry and the public over access to water is readily evident in Louisiana, where there are three major aquifers: The Chicot Aquifer in southwestern Louisiana, the Sparta Aquifer in northern Louisiana, and the Southern Hills Aquifer that serves five parishes around Baton Rouge.

Just two companies in Baton Rouge – ExxonMobil and Georgia Pacific – use more water every day from the Southern Hills Aquifer than all the people and all the other industries in those five parishes put together. ExxonMobil uses about 23 million gallons a day from this aquifer and Georgia-Pacific uses 34 million gallons.

These companies can do it legally because of the “right of capture” that says if you have water underneath your land you can capture it. (On the other hand, if you have oil underneath your land you don’t necessarily own it and you don’t always have the right to capture it.)

The position of these two companies is this: “We’re citizens too. We’ve got a right to that water.” Meanwhile, other companies – Shell Oil and Dow Chemical, for example – use Mississippi River water. But ExxonMobil and Georgia-Pacific insist on using aquifer water – which is also the drinking water for five parishes – because they say the shift from aquifer to river water would cost them too much money.

One of the consequences of the overuse of the Southern Hills Aquifer is saltwater intrusion from the Gulf of Mexico. The water pressure in part of the aquifer is relatively low because the aquifer is being drained too quickly; this creates a kind of capillary action that draws the Gulf of Mexico’s saltwater into the aquifer. It’s a natural process; the saltwater is moving up towards Baton Rouge. When the level of salt in the water becomes too high, the water will be undrinkable.

Then what?

The State Legislature, which is influenced by industry lobbyists, takes the position that if we run short of water from the aquifer, we’ll just drink out of the Mississippi River, as is the practice in New Orleans. The reason they drink the river water is that there’s too much saltwater in their local aquifer.

Another example of industry affecting the aquifers that provide drinking water can be found in Miami, Florida. This city gets most of its drinking water from the upper Biscayne Aquifer. However, waste and untreated sewage are dumped into the nearby Floridan Aquifer, and there are plans to add radioactive waste to the mixture. Studies have shown that this waste could seep into the Biscayne Aquifer.

Problems in the ‘Chemical Corridor’

One of the problem areas for clean water is the “Chemical Corridor” between Houston and New Orleans; it’s dotted with refineries that use huge quantities of chemicals and hazardous materials. These refineries also consume a vast amount of water – and they create a lot of dirty water.

I once got into an argument about an industrial plant that was planned for a city right in the middle of the corridor, Lake Charles, Louisiana. The plant planned to use 14 million gallons of water a day, which would be discharged as warm water into the Calcasieu River after going through the industrial process. One of the effects of doing that is that the fish in the river could be born either all male or all female, because temperature affects the fish population and the sex of the fish. As a result, sooner or later, there could be no fish left.

Nonetheless, one of the big supporters of this project was the leader of the local Chamber of Commerce. He slapped me on the shoulder at a meeting.

“General, this is going to be great!” he said.

“Oh, I don’t think so,” I said, then I pointed out how the plant would pollute the river.

“Well, General, we don’t drink the water here. We use bottled water,” he replied.

He was speaking from the heart, but he had become brainwashed to the idea that it was more important to have an industrial plant than clean water – and that the logical solution wasn’t to try to stop the pollution but to drink bottled water.

Clean water is a human right. But we have been hoodwinked by elected officials who try to convince us that everything should take a back seat to growing the economy. Their defense is that polluting the water system and making the water unfit to drink is an acceptable consequence of creating jobs.

Well, okay, but is the creation of a few jobs or even a few hundred jobs worth 72,000 people in Lake Charles – and many more beyond – having to drink bottled water?

The purpose of the government is to serve the people, period.

As with many other aspects of our society, the concept of democracy in the way we deal with water has been subverted. State and city water boards and water commissions across the nation have become a lot like every other political body.

The idea of our democracy when we won our freedom in 1776 was that the people we elected would look after us and our communities. What’s happened is that the people who run for office are dependent on political donors who expect something in return. Too many politicians have continued to erode the basic principle that the purpose of government is to serve the people; too often, it appears that the purpose of government is to serve business, and the business of water is no different from any other.

In late 2016 and early 2017, there were several controversial oil pipelines that were proposed to run through areas that could be significantly harmed by oil spills, should they occur. A spill from the Keystone XL pipeline in the Midwest could poison the Ogallala Aquifer, which provides drinking water for about two million people and which makes the Midwest the “breadbasket of the nation.”

If the Ogallala Aquifer were to become unusable, the agricultural economy would collapse and two million people would be drinking bottled water.

The system we are fighting against is very, very entrenched in politics. You could go to Texas, California or just about anywhere, and you’d find the same problems. Even though water should be protected as a human right, we’ve allowed it to be monetized, or commercialized. It’s not just that we are over-using the water, it’s that we’re failing to clean it.

Wherever you deal with water, there is a tight-knit group of politicians who know ways to circumvent regulations like the Clean Water Act. Before he was Vice President, Dick Cheney was CEO of Halliburton, the company that patented hydraulic fracturing, better known as “fracking.” This process injects massive amounts of hazardous chemicals into the ground – often adjacent to underground drinking water supplies – in order to squeeze out a few more barrels of oil.

In 2001, Vice President Cheney chaired a special task force that recommended to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) that fracking should be exempt from the Safe Drinking Water Act. In a decision known as the “Halliburton Loophole,” the EPA declared that fracking poses “little or no threat” to drinking water.

Conveniently, the EPA simply ignored information that unregulated fracking can be hazardous to human health and that the fluids utilized in the process can contaminate drinking water long after the drilling has ended. We’ve experienced other dramatic results of fracking, as well: frequent earthquakes in places like Oklahoma that rarely had them before fracking, and drinking water that catches on fire right out of the faucet.

This started in the George W. Bush Administration, but the Barack Obama Administration had eight years to fix it. They didn’t fix it, because they thought it would slow down economic growth if they declared fracking chemicals to be hazardous. As a result, people can now dump fracking water straight into rivers and the Gulf of Mexico, adding to the problems we already face with the “dead zone.”

We’ve got to stop doing stupid things like this. If you dirty the water, you’re responsible for cleaning it.

Cultural shift needed to make water clean again

As private citizens, we want clean drinking water. But this goal is undermined by a few companies that refuse to clean the water they use. That’s not defensible, and the damage that’s being done is long-term. When we allow places like the Gulf of Mexico to be polluted, we’re not going to see that turn around quickly.

We need a cultural shift when it comes to our attitudes about water, just like we had with smoking and AIDS. The cultural shift is happening in parts of California, where they made the price of water such that people have to pay dearly to get a green front yard. In the 1990s, I lived for a while at Fort Irwin near Barstow in California’s Mojave Desert, and everyone had desert lawns with zero- or low-moisture requirements.

At the same time that California is leading this cultural shift, though, their farmers continue to grow crops that need huge amounts of water. It takes about five gallons of water to produce each and every walnut and more than a gallon for every almond.

We need to take the lessons we learned from smoking and AIDS and say, “OK, we had a cultural shift with them, and now we’ve got to stop being stupid with water.”

Everybody needs to buy into the fact that we are responsible for our actions. There are always “save the water” events that focus on what we the people can do in our own homes, like taking shorter showers and not over-watering our lawns – but they never focus on the big industries that are the biggest culprits.

The first thing we’ve got to do is educate the people, because a lot of people don’t understand that we’ve got a water problem and that it’s getting worse by the day. As I noted earlier, it’s not obvious that we’re on the brink of a catastrophe, because we’re surrounded by water.

Clearly, a lot of damage was done to our water resources over the past 50 years. So, what will it be like in another 50 years? We need a long-range, global perspective on water, because as the population grows and sea levels rise, we’re going to have less arable land to raise more food for more people. We’ve got to be smarter about water.

Calls to action

Reduce water consumption.

Fight to enforce the Clean Water Act and Safe Drinking Water Act.

Create technology that can clean water more efficiently.

Reduce fertilizer use on farms.

Don’t let private companies subvert the public’s right to clean drinking water.

Don’t keep making the same mistakes … don’t get stuck on stupid!

0 notes

Text

“Hurricanes, floods and infrastructure failure”

Chapter 4 of Don’t Get Stuck On Stupid!, a book by Lt. Gen. Russel Honore’ (U.S. Army-Retired)

“There is nothing so stupid as the educated man if you get him off the thing he was educated in.” – Will Rogers

One of the big issues facing us in the late 20th century was the so-called Y2K problem, which was the potential for computers to go haywire when their calendars moved from 1999 to 2000. Computer codes were originally written with the year as a two-digit number, leaving off the initial “19.” As the year 2000 approached, experts worried that computers would think “00” was 1900 instead of 2000 and would therefore crash because the date would be off by 100 years.

The fear was that computers running banks, airlines, and even governments would cease to function and that widespread chaos would take over. Nuclear weapons would launch by themselves, ATMs would randomly spit out $20 bills, the stock market would crash, airplanes would drop out of the sky and governments would fail!

I was in Washington at this time, and we were working on the Y2K issue. I spent December 31, 1999, at the Pentagon, watching for signs of trouble around the world. We had forward deployed troops all over the world in strategic sites, and they were ready to go. We had practiced all of the drills to protect Washington, D.C., because we didn’t know what would happen.

Just like everyone else, we did a lot of work to protect all our computers and to make sure nothing happened with our nuclear arsenal. The solution, however, was fairly simple: change the year code to a four-digit number – but with so many computers and so much data, there was a possibility of missing something.

As it turned out, nothing happened, but it showed us how vulnerable we were to infrastructure failures – and that responding to a crisis takes much more effort, time and money than simply planning ahead.

A changing climate requires changing ideas

Other than Pearl Harbor in 1941 and the terrorist attacks in 2001, never before in our country’s history have we faced a crisis at home that is as immediate and important as the one we face today from our crumbling and badly managed infrastructure.

But it wasn’t the Russians or a terrorist network

that did this to us. We did it to ourselves by ignoring the warning signs and not making adequate preparations.

This crisis has been known about for many years, but it really became evident in the summer of 2017 when the triple hurricanes of Harvey, Irma and

Maria hit Texas, Florida and Puerto Rico, respectively. Every day for several weeks on end, we turned on our televisions and checked the Internet for updates on the disasters that were unfolding in several major metropolitan areas and across the entire island of Puerto Rico.

Even after disasters like Hurricane Katrina in 2005, it’s frustrating to think that planning on the ground still hasn’t been implemented to avert disasters of this nature. This is something we are very capable of doing – just like we have done to improve hurricane tracking. We might be able to predict with a new level of accuracy where a hurricane may strike, but in general we are not using technology and scientific research nearly enough to help our people. It’s possible to use these resources so much better, but politics and various vested interests have taken precedence over the well-being of our country.

We are at a critical point in history – not just for our national security, but for our health and safety and the future of our country. That’s why it’s important to take a different approach, because we can’t depend only on the professionals and the politicians to make things better. In many instances, they haven’t even addressed the issues in earnest. Someone needs to raise the distress flag.

If our people aren’t safe, our country is vulnerable. The only one who can save us is us.

One of the greatest issues we face is that weather patterns are changing. This severely affects the way in which our houses, our neighborhoods, our cities, our states and our entire nation have to deal with such dramatic and immediate changes. This is not just a societal issue, it is a national security issue.

The weather and infrastructure may seem like separate issues, but they’re well connected. If our roads and railroads, for example, are not adequate in times of emergency, large sections of the population will be in even greater danger from the floods and hurricanes that we know will be coming.

Something needs to be done to defenseless areas to mitigate problems caused by severe weather events; many of these problems were exposed by Hurricanes Harvey in Texas and Maria in Puerto Rico.

An egregious example of how we have created our own problems is that we have allowed developers to build entire neighborhoods in known floodplains – in Houston, Texas, for example. About 90 percent of all natural disasters in the United States involve flooding, so most insurers no longer offer flood insurance because it is not profitable. As a result, the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) was introduced in 1968 to provide flood insurance to communities that otherwise might not be able to purchase such insurance.

The majority of the NFIP’s 5.5 million policyholders are in Texas and Florida, the very states that were pummeled by hurricanes in 2017 and two of the states that are most vulnerable to climate change and rising sea levels. Before these hurricanes, the NFIP was already over $24 billion in debt, due in part to bad management and ill-conceived policies.

The NFIP debt is taxpayer money, so we’re subsidizing people to build in areas that we know will flood and will need to be bailed out. That’s crazy! In fact, just one percent of insured properties account for up to 30 percent of the claims and represent more than half the $24 billion debt, meaning that some properties flood multiple times and are constantly rebuilt, with our government knowing they will flood again.

More than 30,000 properties flood an average of five times every two to three years, and some properties have flooded more than 30 times. One home valued at $69,000 in California flooded 34 times in 32 years. Yet, after every flood, the NFIP rebuilt the property, spending nearly 10 times the property’s value.

What’s more, the average home that’s flooded has a value of about $110,000 but suffers over $133,000 in flood damages – and many of these homes are rebuilt multiple times. A significant number of these homes are also vacation homes, meaning that money to help rebuild primary homes for the less wealthy is potentially being diverted. It would often be less expensive to purchase a new home in a different location than to keep rebuilding in the same location.

We know the dangers and the expenses of living in flood zones, but little is done to help people move out of them. Apart from the insane policy of rebuilding over and over again, less than two percent of the money spent on rebuilding is spent on helping people move to safer locations. Unlike a nation such as the Netherlands – much of which is below sea level but which has not experienced a major flood since 1953 – we spend more money responding to floods than preventing them.

To make matters worse – or better, if you’re covered by NFIP – is the fact that the insurance policies don’t increase in price, even after multiple claims for the same property. When efforts are made to increase the rates, there is a huge cry from those whose premiums would increase because they rebuild so often. Meanwhile, we the taxpayers are footing the bill and literally encouraging people to build and rebuild in places that are not sustainable for housing.

After a disaster, many people are clueless about how to rebuild. How many more disasters will we have to go through before things are done right?

One of the issues we see in storms such as Hurricane Harvey is how to manage storm water. There is a normal function of the landscape and the way it deals with things such as excessive water, but that understanding has disappeared along with the natural landscapes that help the land deal with storm water.

The landscape is a huge mechanism for absorbing and purifying rainwater. Under normal circumstances, regular rains help cool the atmosphere; at the same time, the rain is soaked into the ground, where it is naturally filtered and becomes safe to drink. What we’ve done over the years is that we’ve changed this mechanism so that it is no longer functioning as it should.

Storms are ways of equalizing heat in the atmosphere, and one reason we get these huge storms now is the concentration of hot air and hot water. That’s what fed the storms in Texas and Florida in 2017. The atmosphere is heating up due to the reduced amount of plant material, which increases the moisture drawn into the air and therefore the amount of water that is dropped as rain. It’s a vicious cycle.

The energy in the atmosphere also plays a major role. The jet stream usually goes west to east in a fairly predictable pattern, but now it is waving up and down, more than likely due to man’s influence on the atmosphere. When the jet stream goes above or around a storm, it no longer pushes it. This is contributing to more extreme weather and making the extreme weather last longer.

One of the things that rain does is slow the wind, so with more rain we can expect slower-moving storms. We have already seen the effects of storms that sit for longer periods instead of moving along like they used to do. The floods in south Louisiana in 2016 and Hurricane Harvey in 2017 are examples of this new trend in storms.

Forests are one of the planet’s biggest cooling mechanisms, but we have replaced great swaths of forest with lawns. The lawn is now the single largest “crop” in the United States. More lawn is grown in our country than corn or any commercial crop, and in total it covers an area about the size of Texas.

The proliferation of lawns comes at a great cost, however. It takes a tremendous amount of water to keep grass alive, and in some regions as much as 75 percent of residential water is devoted to lawns. Naturally, this puts a colossal strain on water systems. The typical lawn uses 10,000 gallons of water per year, in addition to rainwater.

Unlike trees, which absorb carbon dioxide, lawns emit considerable amounts of carbon dioxide, which contributes to the warming of the atmosphere.

The greatest harm a lawn does, however, is as a result of their being treated with chemicals. After World War II, the chemical companies led us to believe that the best lawns were bright green, weed-free and insect-free, instead of being natural.

Each year, we dump about 90 million pounds of herbicides and pesticides on our lawns, with the result that many of these chemicals are now found in groundwater. Nitrates leeching into the drinking water can have the effect, as seen in some states such as Iowa, of turning babies grey-blue (the Blue Baby Syndrome).

What all this chemical action does is alter the nature of lawns. In a natural, organic lawn or forest floor, you could have four or five inches of rain with no runoff because the water is absorbed. A chemical lawn is denser and less able to absorb water, because the chemicals undermine the biology of the soil. It becomes saturated after only an inch of rain, and the rest runs off.

In a heavy rain, a typical sewer system can usually handle only a couple of inches of rain. After that, the landscape starts to flood. In an era when we are facing heavier and more sustained rainfalls, it makes sense to return to lawns that are organic and that can handle large amounts of water – or, better yet, replace lawns with other vegetation that is not harmful to the environment.

Another issue is trees. Tree roots are being starved by lawns, again because the rain is not being absorbed adequately into the ground. Instead of lawns around trees, it’s best to use other types of plant materials or no plants at all, like our grandparents used to do. Every person that owns property has the ability to contribute to the revival of healthy lawns and healthy trees, with the ultimate goal of being able to deal with storm water.

Insurance companies don’t like people to have trees near their houses, because trees have a habit of falling on houses in storms. However, trees almost always fall because of bad management, not because of wind and rain. Trees are valuable, because they cool the environment, provide shade that cools houses, and break the wind. Rather than getting rid of trees, we need to understand how to maintain our trees to encourage healthy soil and healthy roots.

Infrastructure is the foundation of our society

South of the confluence of the Ohio and Mississippi rivers at Cairo, Illinois, there are just five railroad bridges crossing the Mississippi River. Known as the Lower Mississippi, this is a stretch of about 1,000 miles.

One of the reasons there are so few railroad crossings in the Lower Mississippi is that about 90 percent of all railroad freight traffic across the nation – both east-west and north-south – passes through Chicago, in the North. This makes the entire nation’s railroad freight system vulnerable to a crippling weather event such as a snowstorm.

Chicago is known for its extreme winter weather, and the blizzards of 1967 and 1999 are particularly memorable. In 1999, a blizzard virtually shut down freight traffic across the nation for several weeks. Because each railroad company is privately owned and operates its own lines, they didn’t coordinate their snow plowing and they were on the verge of shutting down the nation’s freight system. Fortunately, the railroad companies worked out a solution by allowing train cars from one company to go from one railroad line to another.

That was an infrastructure challenge, and it was solved because people realized there was a problem and they fixed it. It didn’t address the crazy situation in which 90 percent of railroad freight traffic goes through a single hub, but it was a start.

The railroads are still all privately owned, but the roads and airports across the nation are owned by various governmental entities, so we have this matrix of transportation infrastructure that is a patchwork of business and governmental bodies. And this can sometimes be a huge mess.

This is just one piece of the infrastructure jigsaw puzzle that keeps our nation running, but if any part of it fails, it could have a devastating and cumulative effect. In any community, the citizens can point to crumbling bridges, roads that are inadequate for the amount of traffic, sewer systems that need to be upgraded, school systems with inadequate facilities and so much more. As our infrastructure ages, the need to upgrade and replace it increases – and so does the cost.

Infrastructure is the foundation of our society. Without roads, bridges, schools, power plants, hospitals, communication systems and so on, our quality of life would plummet and we would become a third-world country.

Politicians tend to want to take the easy way out. Often, this means ignoring the problem and leaving it for the next administration or proposing privatization for parts of the infrastructure. The United States, through Federal, State and local governments, spends about 2.4 percent of GDP (Gross Domestic Product) on infrastructure per year, which is much less than many other developed countries.

China, on the other hand, spends about nine percent. In dollar terms, it spends more on infrastructure annually than North America and Western Europe combined. China, like many other nations such as Germany and Japan, looks to long-term goals. Meanwhile, the U.S. generally has shifted away from long-term goals to short-term fixes.

President Dwight D. Eisenhower understood that solid infrastructure is a military weapon. One of the major rationales he used in support of the interstate highway system was that it would facilitate the efficient movement of troops and military equipment across long distances.

Today, one of the easy political solutions to failing infrastructure is to propose privatizing large parts of it, most notably roads and bridges. Private companies alone are unable to finance the huge costs of these infrastructure projects, so they are granted massive tax breaks and are allowed to collect user fees such as tolls to offset their expenses.

This may work for some high-traffic spots in major metropolitan areas, but it will never work for rural roads and bridges that see relatively little traffic but are equally essential to the livelihood of the local population. The other issue is that the roads and bridges are still built with taxpayer money (in the form of grants and tax breaks), yet the taxpayers are charged tolls to use the very things they have already paid for.

Overall, transportation needs to be looked at more closely, and we need a variety of options so that if one part of the system breaks down, there is a backup. Currently, there is no backup, which is why one small failure in the highway system, for example, can cause weeks or months of disruption. Thus, a major blizzard has the potential to cripple cross-country rail networks.

‘Houston, we have a problem’

The situation in Houston in the aftermath of Hurricane Harvey in 2017 was the “perfect storm” of infrastructure failures, environmental mismanagement and changing weather patterns. It was as much a man-made disaster as was Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans 12 years earlier.

One of the biggest issues in Houston was the lack of zoning and building codes, which are essential components for urban growth. Houston is the fourth-largest city in the U.S. in terms of population and the third-largest in area. More than 2.3 million people are spread out over more than 630 square miles.

Most cities have stringent building requirements. In San Francisco, which has a high population density because the city is confined to a small area, there are higher standards for buildings due to the threat of earthquakes. In addition, they don’t build where there could be floods, and residential and business areas are strictly separated.

In Houston, much of the city was built in known floodplains. Houston was planned by developers, apparently with little thought given to how the various communities would deal with the inevitable floodwaters. Houston is a concrete jungle that floods regularly: The first major flood was in 1935, and since 1994 it has flooded several times. There was a 100-year flood in 1994, a 500-year flood in 2001, and devastating floods in 2015, 2016 and 2017.

The 2017 flood was the worst, of course. With so much of the land paved over, with so many lawns unable to absorb more than an inch or so of rain and with Hurricane Harvey being bigger and slower than previous storms, there was simply nowhere for the water to go.

To make matters worse, the lack of building regulations meant that not only were thousands of homes built in floodplains, but when there was a plan to deal with excess rainwater it often involved simply moving that water to the next community via pipes, ditches, and so on. This total lack of infrastructure planning made the environmental disaster worse than it should have been – and completely predictable.

It’s not just Houston, of course, although we know that many of the problems faced by Houston could have been averted or lessened with sensible and proper planning.

Just weeks after Harvey hit Texas, Hurricane Maria slammed into Puerto Rico, severely damaging the island’s fragile infrastructure and knocking out power to almost the entire population of about 3.5 million people.

Instead of doing all in his power, as quickly as possible, to help millions of American citizens who were without electricity and were running dangerously low of drinking water and food, President Trump belittled the island’s elected officials, calling them “politically motivated ingrates” who “want everything done for them.”

The inadequate Federal response in Puerto Rico was all too familiar. I had seen it before in 2005 in New Orleans – and here we were a dozen years later and we were still stuck on stupid.

Overall, we’re facing a national crisis that could affect 60 million people in low-lying and coastal areas. As a nation, we have no plan to protect those people. There is no Federal agency for planning a response. And the Trump administration is making matters worse by denying there is a problem, refusing to accept the scientific evidence.

One way to be better prepared for future hurricanes is to enlist the aid of the U.S. military – a “Ready Brigade,” a quick-response Task Force that could move in immediately after the storm has passed.

This Task Force would be made up of Army, Navy and/or Marines. It could be drawn from the Army’s 82nd Airborne Division, or the 101st Airborne Division, or the 10th Mountain Division.

The first of the military personnel could be on the ground in a matter of hours, assessing the damage, saving lives, helping people in distress. Such an operation would involve perhaps 15 to 20 ships, 100 helicopters, and a brigade of soldiers, including some who would parachute into the heart of the affected area.

I think Congress should authorize the funding in the Defense Department budget that would enable such a Task Force to be our nation’s first responders

for disasters involving hurricanes of Category 3 strength or higher.

Now, the Task Force wouldn’t take the place of the various State National Guards and other first responder groups that have been at it for decades. It would supplement what’s already being done, and it would do so with extraordinary speed, the likes of which the world has never seen!

It would be easy to slip backwards into being a third world country. We planned our metropolitan areas to be densely populated, but we haven’t put enough thought into how to support that population in times of crisis.

How do they evacuate?

How do they survive if the railroads fail or if the electricity supply fails?

How do they deal with floodwaters?

Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans in 2005 was a learning experience. Mistakes were made, but there was no precedent. Katrina became the precedent and was the starting point for how to deal with future disasters. Houston, Florida, and Puerto Rico incorporated some of the lessons, but neglected others.

The compromised infrastructure across the United States is a serious threat to national security, and it’s made worse by changing weather patterns and cities springing up where they perhaps don’t belong.

We have vested interests in keeping the status quo, but the status quo is rarely favorable to the population at large. Human nature never changes, and those with power don’t want to relinquish it. Unless we learn from history, we are doomed to repeat it – and the failure to learn from Hurricane Katrina is already having serious implication for our ability to deal with today’s monster storms.

What we have to understand is that the price tag to keep Americans safe isn’t the main issue. Look at the amount of money we spend on overseas wars and defense contracts. If we spent just a fraction of that on being prepared for disasters at home, we would be better able to take care of our own people.

The fact that we are failing in our duty to protect our own people is not just stupid, it’s shameful and grossly negligent – but completely reversible if we can muster up the will to address these issues.

Calls to action

Accept the reality of changing weather patterns, and plan accordingly.

Build sustainable houses and rebuild in safe places, not in floodplains.

Don’t use chemicals on your lawns.

Help trees work with the environment, not against it.

Devote time and effort to building a strong infrastructure.

Don’t keep making the same mistakes … don’t get stuck on stupid!

1 note

·

View note

Text

“The global environment”

Chapter 4 of Leadership in the New Normal, a book by Lt. Gen. Russel Honore’ (U.S. Army-Retired)

U.S. citizens used to feel we were protected by two oceans, that the Pacific and the Atlantic shielded us from the eyes of the world. But now that shield has been destroyed by invisible electronic signals connecting phones and computers to the Internet.

Now the whole world can see that the U.S. has 5 percent of the world’s population and consumes 25 percent of its resources.

What of the other 95 percent of the population? Of the approximately 7 billion people in the world today – of which the U.S. has 314 million – about half live on less than $4 a day.

Of course, they’re wondering why they’re so poor and we’re so rich. And you can bet they’ve also noticed that the Western world, with the United States leading the pack, is consuming more than its fair share of the world’s resources.

Up until the early 1990s, the rest of the world didn’t know how well we live in the West. And that suited governments of lots of other countries just fine.

For one thing, the leaders of those countries feared “brain drain” – the flight of the best-educated to the West, where the jobs are better. Secondly, obvious disparities in wealth raised and continue to raise an uncomfortable question, especially among the staunchly religious: If God favors us, why are we living so poorly and others are living so well?

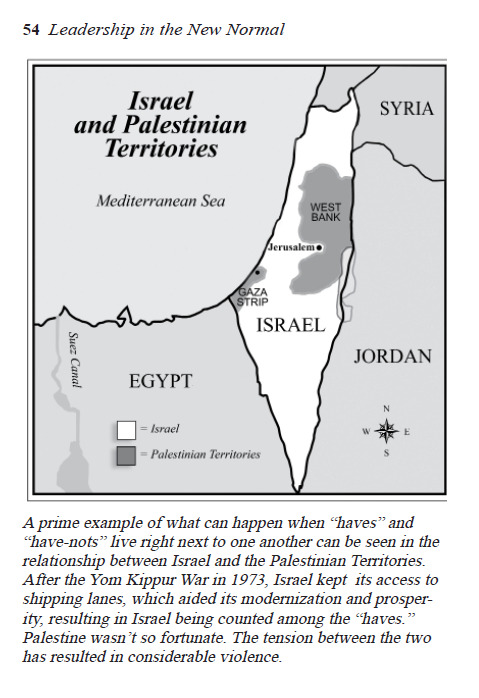

The question is a whole lot harder to resolve and has much worse consequences when the people living better than you are living in the same place as you. We began seeing a good example of this in 1973, after the Yom Kippur War in the Middle East.

Israel grew in size after a buffer zone was established between it and Palestine. Israel retained access to water, particularly the Suez Canal. That gave Israel access to shipping lanes and helped its economy become industrialized and technologically advanced. Palestine didn’t have these advantages and still doesn’t.

As a result, that tiny area of the Middle East became a case study of what happens when haves and have-nots share space, when have-nots can see how much better others are living. These days, have-nots can see the haves on any Internet-connected screen. And they don’t like what they see.

Imagine this attitude of envy on a global scale. You don’t even have to imagine it – it’s on every TV news channel every night.

The culture of poverty exists all over the world, and so does the response to it: violence. Poverty and the culture it creates can even foster terrorism.

If you think you’re not being treated fairly, if you think your resources are being exploited, if you think others benefit from your poverty, and you think they have no God-given right to do so, your response may well be to get ahold of a rock. Or a gun. Or the controls of a plane.

The morning of September 11, 2001, we thought we were protected by two oceans and large expanses of terrain. By lunchtime we realized that we are incredibly vulnerable. Worse, we realized that something we’d become very comfortable with, the airplane, could be turned into a weapon that could be used to kill a lot of people. Not an airplane with a bomb, but an airplane with an angry man on it. That realization changed our culture as we knew it. By the evening of September 11, we started treating people trying to get in our country, and immigrants already here, like possible terrorists.

That’s part of our New Normal.

The prudent use of power in the New Normal

Abraham Lincoln once wrote, “Nearly everyone can stand adversity, but if you want to test a person’s true character, give him power.”

That was true in Lincoln’s day, and it’s true now.

In the world in which we live today, the interconnectedness of everything creates new tests of leadership and new ways of using the basic levers, or instruments, of power.

There are four kinds of power on a national scale: political, diplomatic, economic and military.

Political power is legislative. Everyone has at least some access to political power – through the vote in a democracy, through resistance in non-democratic nations.

Diplomatic power is more curtailed, more intricate. Fewer people have direct access to it because diplomatic power refers to an effort to resolve issues through discussion and compromise.

Economic power results from a nation’s financial position. The more money a country has, the more economic power it can command. And economics is very powerful. We may think trade agreements are all about money – but when the commodities being traded are food or water or medicine, economics becomes a life-or-death issue.

Military power is the fourth form of power. As a retired general in the United States Army, I feel confident in saying this: Military power is probably the most inefficient method of resolving an issue. The world is not necessarily scared of the U.S. military. There are only so many places we can go at any given time. A nation should use military power only when none of the other levers of power works – war as a last resort.

The military theorist Carl von Clausewitz said that war is the continuation of politics by other means. I’d say war is the failure of politics. The day we invented the nuclear bomb was the day we could no longer afford to fail at politics. The stakes are too great. The New Normal alters war and politics, too.

The reason no nuclear country has dropped a nuclear weapon since World War II is because mutually assured destruction is a stupid idea. But these days, too many groups can get hold of a “nuke.” Wild-eyed warriors, people with an axe to grind and an enemy to kill, have access to nuclear technology and materials.

There’s no place you can be in the world and not be affected by terrorism. If a terrorist decides to attack you because of what you do or what you fail to do or the government you have or don’t have, you’re not immune to his plans.

True, more U.S. citizens will get killed this year from car wrecks or cigarette smoke than by terrorists, but we’re more afraid of terrorists. That’s because we’re more aware of them. We see and read and hear about them all the time.

That can make us want to become isolationists. Many of us don’t want to learn about the cultures outside our borders; we don’t want to learn another language. We don’t even want to learn the languages of the immigrants who live here in pockets and pools, and those pockets and pools keep immigrants from learning English. It certainly isolates them from the larger U.S. culture.

The desire to isolate ourselves is an easy temptation, but it’s limiting. Isolation makes us less intellectually curious. The military has learned the danger of that attitude twice in recent years – once in Iraq and again in Afghanistan. Your servicemen and servicewomen have come to realize that a clear understanding of other cultures and customs is essential in the New Normal.

America’s last big innovations were focused on warfare. We were very interested in developing the computer because of its ability to help us do the computations we needed for weaponry. We put satellites in the air, not for commercial use, but to spy on other countries. The U.S. Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) created the Internet as a means of communicating with Navy submarines and essential personnel in time of war. All these innovations were driven by warfare.

But times have changed.

Now, when we look at the instruments of national power, we should consider how to use them to help make this world a better place for us and others to live. We should take the traditional instruments of power and use them differently.

Bigger armies will not be the answer. My guess is that most military leaders are well aware of this. They understand that the military isn’t the solution to every power struggle, and that the U.S. can get a lot further with economic, diplomatic and political applications of power.

To use that power, we have to understand the people on the other side of the table.

But most leaders aren’t military commanders. Most leaders today have different kinds of demands and problems.

So, why should they bother to learn about other countries’ cultures and languages? Really, unless and until someone flies a plane into our office, why should we care about what the have-nots think?

Because our future and our safety are not in becoming more isolated. Our future is in becoming more global. In the New Normal, we’ve got to be more attuned to economic and environmental change. The shifts won’t be as big as they were from the agriculture age to the industrial age, from the industrial age to the information age. But they are much, much more interconnected, they’re much faster, and they have the potential to affect every living person – for the better.

We can’t ride these shifts peacefully if we’re terrified of the rest of the world. For that reason, we shouldn’t be alarmists. Instead, we should be opportunists.

Helping to create ‘haves’ from ‘have nots’

In the late 1990s I spent two months working with the Egyptian Army, training some of their officers in certain military techniques and strategies that have been effective for the U.S. military. The Egyptian government provided me with a driver, a real bright guy with a master’s degree in English. The Egyptians hired him as my driver because he spoke English, so he could report everything I said and did to the Egyptian Army. He had a dual role, and we both knew that. So I was careful about what I said and did.

Now, this man had a solid job teaching English in Cairo, but he quit his job for a month and a half to drive me around. Why? Because he made more money driving my car for six weeks than he made all year teaching.

So I couldn’t help thinking, as I watched him from the back seat, that when people invest in an education and don’t get a reasonable return on it, when education doesn’t raise your family’s standard of living, there’s going to be a problem.

Years later, I watched on TV as thousands of protesters filled Tahrir Square. I watched them demand that Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak resign. They got what they wanted, and I wondered if my driver was one of the Egyptians in Tahrir Square.

Think back on all those people living on $4 a day, watching us on their cell phones. Some of them are furious that they have so little while others seem to have so much. Some are furious that God doesn’t seem to have spread the wealth fairly. Some are picking up guns to even the score. But what all of them have in common is want. They want something. If the U.S. can help them get it, we benefit and so do they.

I’m not suggesting a massive socialization of the world, and I’m not talking about a capitalist Trojan horse. What I’m saying is that people who can feed their families and feel like they’re getting somewhere in life are less dangerous people.

The Gallup Organization is doing a 100-year World Poll. They’re a few years into surveying the whole world and have already come up with some key findings. First, what everyone in the world wants is a good job. More than peace, more than security, what everyone from a Los Angeles lawyer to a Laotian laundress wants more than anything is a good job. When people have a job, especially a good one, they have something to protect. They have something – and that makes them haves instead of have-nots.

That doesn’t mean half the earth should be the United States’ charity project. We’ve seen what happens when unstable governments get their hands on a lot of foreign aid; in some cases, they use it to buy guns to shoot their own people. Angus Deaton, a respected Princeton economist, thinks that if the West wants to send aid to emerging economies we shouldn’t send checks, we should send doctors and well-diggers.

Years spent in emerging countries assure me Dr. Deaton is on to something. But I’ll go further: Helping developing countries develop businesses is even better. Helping the have-not countries create good jobs that stabilize their societies and keep their folks fed and progressing is better for them than an endless stream of money. And this can be good for the West’s export economy, too.

We should help poor countries build their economies as a form of internal security so they can take care of their people. When a society can’t take care of its people, it has not only political unrest, but the potential for tyranny as well.

So, in the New Normal, where distances don’t protect or shield us, we have two choices: We can look at the rest of the world as a threat, or we can look at it as an opportunity. We can arm ourselves to the teeth and send our military out to fight the have-nots, or we can invite the have-nots into the first stages of a business relationship.

I think there isn’t much of a choice. Military solutions should always be solutions of the last resort. Wars cause new problems, often worse problems. Instead of living in perpetual war-readiness, we should understand the global environment and willingly take part in it. And it’s better for all of us if we hurry up and get to it.

Exporting: The key to economic growth

The United States is fourth on the list of world exporters. Nine percent of our exports are agricultural products, 27 percent are organic chemicals, 49 percent are “capital goods” (transistors, computers, car parts, telecommunications equipment), and the rest is made up of things like cars and medicine.

Nonetheless, the vast majority of the U.S. economy is driven by our “shining each other’s shoes,” so to speak. Somebody fixes my refrigerator, somebody fixes my car, I give a speech to a group. That’s an internally generated economy, and that’s good. But it won’t get us very far. What separates growing economies from stagnant ones is exporting. Growing economies export more than they import.

In the New Normal, we all – every single country – have to be exporters. We all have to produce goods that other countries want to buy. We all have to be in fair, respectful, mutually beneficial business relationships with others. You know why?

For one thing, no one ever sends a suicide bomber to kill his counterpart in a respectful, mutually beneficial business relationship. And because such relationships turn have-nots into have-enoughs.

North Korea and South Korea are excellent examples of this. South Korea, where I served for several years, came out of the Korean War poor as dirt. I mean absolutely poor to no end. When I got there in 1971, they were still using draft animals. Nonetheless, they found the energy and resources to focus on educating their children and on developing a democracy.

Now, 60 percent of South Korea is covered in mountains – not the best terrain for a country that lives on rice. So to support themselves, they produce rice in the valleys in small plots. But to enrich themselves, they concentrate on industrial production. Because of their focus on education, South Korea had the smarts to engage in, and sometimes dominate, the technological field. As a matter of fact, much of the work done on American animated movies is done in South Korea.

North Korea came out of the same war just as poor – and only got poorer. We don’t know how poor because Kim Jong-il didn’t want us to know. But some escapees report starvation on a massive scale, almost total lack of medical care, and an economy based on what amounts to slave labor.

China deals with its economy and population differently. China doesn’t keep that big army to fight the United States; they keep it to control their own people. I’m not sure how much longer the Chinese government will be able to maintain its control. The country has a long history of peasant uprisings.

But for now, China has a thriving market-driven system because that’s where the money, security and peace are. The Chinese government is in no hurry to help North Korea lift itself out of poverty because a thriving middle class just over the border might foment unrest in China.

The differences between South Korea, North Korea and China illustrate the differences in an open, democratic society; a closed communist society; and a semi-capitalistic society.

An open society tells you that if you want to be successful, you get an education. You work hard and the country will provide the security and the opportunity you need.

Closed societies, like the oppressive regime in North Korea, emanate from the communist culture that says everybody is in it together, shares alike, and is rewarded the same. Of course, it never works that way. In closed societies, a few people get all the power, most of the people do all of the work, and only the powerful prosper.

A semi-capitalistic society understands the power of money: It funds a lot of projects, keeps people happy, and permits the maintenance of a huge army. But semi-capitalistic countries have a choke hold on their own potential, and it’s hard to let that go.

Cuba has a lot in common with the closed society of North Korea. Before Fidel Castro took power, Cuba had the rich, the middle class, and the poor. Castro drove out the rich, ruined the middle class, and created a nation of poor people who produce less food now than they did in the 1950s. Cuba used to be able to feed itself. Now Cuba has to spend the little money it makes to import food. Its climate is identical to Florida’s, and Florida is an agricultural powerhouse.

So, how can Cuba become another South Korea? How does any economy become an exporter? And how do we in the West help them do it?

First, we’ve got to help the rest of the world get things like information technology and increased farming capabilities.

Poor countries’ success won’t result from the amount of grain we export to them, but the amount of grain we show them how to grow and process themselves. That will give them the ability to feed themselves. Kids who go to school with full bellies can learn, and a nation of educated people can grow an economy.

It can happen. I’ve seen it. Take Ghana, for instance. Ghana has a population of 18 million people, and it has a favorable climate. They have some rainfall and they have some arable land – advantages that countries like neighboring Somalia don’t have.

Ghana’s food staple is rice. If you were to go and walk around in Ghana, you would notice that they have more rice fields than anything else. What they don’t have is ample capacity to process all that rice. So they have to buy processed rice from overseas, which consumes a good 20 percent of their national capital.

It doesn’t take much to process rice. Just check that it has the right moisture level, shell it, then put it in a bag. That’s rice processing. But Ghana doesn’t have enough machines to check moisture levels and shell rice. Thus, they had rice they harvested two years earlier just sitting around, but they couldn’t process it.

So some folks in Ghana sought help from an American company, a company for which I consult. I gathered and studied all sorts of information about their rice farms and discussed it with some Ghanaian officials.

We evaluated alternative strategies for increasing rice production and processing capacity. Long story short, they decided to use parts of the Asian model and parts of the U.S. model.

Today, Ghana is developing its large rice farms, and at the same time retaining its small family farms. Small farmers grow the rice and then send it to large farms which have the capability to process and export the rice.

The big farms focus on the export economy, while the small farms make sure there’s enough rice to eat in Ghana. If Ghana had the machinery and the mills to process more rice, they could actually be a major exporter of this product.

Now, here’s another thing to consider: Ghana has oil. Several foreign countries have come in, done some exploration, and sunk some oil wells. Those wells are going to be making Ghana some real money. But instead of putting the money in the army, Ghana’s planning to put the money into developing its economy.

I think Ghana understands – unlike Togo on the east and Cote d’Ivoire on the west – that basing an economy on a single resource like oil can be a big mistake. Cote d’Ivoire, the Ivory Coast, is raging with political unrest over who’s in charge and what tribes are going to lead the country. In other words, who’s going to get the oil money? Cote d’Ivoire has the resources to be a self-sustaining country, but seemingly they would prefer to use the money to slaughter each other.

What will really save Ghana, or any country, is a balanced economy with good jobs. That starts with schools; everything starts with a good education. No kid of my generation in Lakeland, Louisiana, was allowed to forget it. What drove our generation was the certainty that if you got an education, nobody could take it from you. You could literally do anything you wanted if you got an education. My teachers said it so many times, I could finish their sentences while they were still talking.

Education is the key: You graduate from high school, you get through college, and you can do what you want with your life. Your way out of poverty is education. I believed it, and I’m glad I did because it’s true: Education is the road out of poverty. Now, the New Normal is teaching us that education not only changes individuals, it changes countries.

School makes all the difference in the world because the education system drives diplomatic, economic and military power, and the most dynamic of them is economic power. Countries build economic power through education. And the countries that provide equal education for boys and girls are the ones that will succeed to the greatest degree now and in the future.

What the world needs now: a culture shift toward education

The number of children growing up in one-parent households in the U.S. has skyrocketed.

According to the Annie E. Casey Foundation, this is the case for 65 percent of non-Hispanic black children, 49 percent of Native American Indian children, 37 percent of Hispanic children, 23 percent of non-Hispanic white children, and 17 percent of Asian-American and Pacific Islander children.

This is a change that’s happened inside a single generation. In 1970, only about 10 percent of babies were born to unmarried mothers. Today it’s nearly 40 percent.

I don’t think it’s a coincidence that states with the worst education records and the poorest people tend to have the highest rates of unwed pregnancies. I’m not picking on unwed mothers. In the 1950s and 1960s, unintended pregnancies often led to shotgun weddings, which probably had a lot to do with the exploding divorce rate of the 1970s.

And I’m not saying that kids born to unwed mothers are doomed. President Obama was reared by a single mother and spent only a few weeks in sight of his dad. Yes, single mothers can rear happy, healthy kids who become successful adults. But the data show that it’s a whole lot harder for one parent to manage than it is for two parents.

The Casey Foundation sums it up this way:

“One-parent families are more likely to experience economic hardship and stressful living conditions – including fewer resources, more frequent moves, and less stability – that take a toll on adults and children alike. When economic hardship and stressful living conditions are present, children are at greater risk of poor achievement as well as behavioral, psychological and health problems.”

When I was in the Army I was sent to Bangladesh to observe the political and economic landscape. The government attached a “minder” to me, a military officer who took me around and showed me what the government wanted me to see.

One of the things I saw was a woman with a baby strapped to her back, kneeling in the dirt, breaking up rocks by hand.

I asked the minder why she was doing it, and he said because the road crews needed gravel. I asked him why the managers didn’t just get a machine to do it. Breaking rocks is hard work anywhere, but in the Southeast Asian sun it’s brutal. I’d hate to see a 6-foot-6, 300-pound American football player doing that kind of work for a day, so it was disturbing to see a young gal and her baby at it. I said something along those lines to my minder. He looked at me as though I had no sense at all.

“She does it,” he said, “to earn money. If we got a machine, she and her baby would not be able to buy food.”

Here’s the point of the story: That woman was doing work we in the U.S. don’t let hardened criminals do, and she was doing it with a baby tied to her back – and that child is likely to have as successful a future as many of the kids on Railroad Street in the U.S. That child may not have enough food, he may never get much of an education, and the political situation will probably be unstable his whole life. But his mother cared about him enough to break rocks to support him, and his community cared enough to make sure she had a job.

On the flip side, though that child may be well-loved, well-cared for, and well-reared, his chances in life are limited. Odds are he’ll grow up to break rocks for a living. Two things will save him from such a hard life: either phenomenal good luck, or a fairly average education.

That’s a fact in every society. Rich kids need an education, Bangladeshi kids need an education, Railroad Street kids need an education. Education changes everything. But to get an education, the community has to value education. In some places that requires a significant culture shift, but it can be done.

The people to lead this change are the leaders – in the government, media and academia. When change comes, it comes from there.

Consider how the public became educated about AIDS and how to prevent it. The first cases were detected in 1981, the disease was named in 1982, but it took a long time before leaders dared talk about it in public. It was a long time before anybody talked about it. I still remember the day our third-grade daughter came home from school with a very surprising request.

“Dad, tell me about AIDS,” she said.

I was shocked. I was a young captain on duty in Germany, and the Army had started doing AIDS testing, but I was totally shocked that children knew about it.

But the academics got busy studying what the disease was and how it spread, the government started implementing ways to stop the contagion, and the media picked up a megaphone to tell people how to protect themselves. Hollywood started coming out with heartbreaking movies about people dying from AIDS. Government, media and academia – they brought it out from the shadows and into the light.

All that talk caused people to think about their behavior. Soon we were bombarded with information in the schools and through public policy channels, we had a very vocal Surgeon General, and you couldn’t turn on the television or open the newspaper without seeing a reference to AIDS. It scared the hell out of people.

But that government-, academic- and media-stoked reaction caused a cultural shift. By 1987, the first anti-viral medication went on the market, and we got that terrible virus tamped down.

When government, media and academia work together, cultures shift.

What the world needs right now is a shift toward education. Education can turn neighborhoods from crime-ridden blights to decent places to rear a family. Education can turn poverty-stricken countries into self-supporting ones. Education can turn violent societies into viable ones.

Your mission as a leader in the New Normal: Grow your organization

Something else education can do is to prepare people to make the things the world needs and sell them at a profit. As I mentioned earlier, every single country needs to be an export country. To be an exporter, a country has to make things that other countries want to buy. Educate enough kids, and you’ll get the people who make those things. Sell enough of it, and you’ll help stabilize your country.

But sell the right things, and you’ll make the whole world a better place. Sell the right things, and you’ll make yourself and your country a whole lot of money along the way.

Companies that can take a broad view, an educated view, are going to own the New Normal.

What if there was a battery that could power a house for three days? Or, better yet, one that could power a refrigerator in Africa for a month so that food could be stored against days of scarcity?

What if that household in Africa could afford the battery because some smart person built it inexpensively?

What if we could teach computers to taste and smell? What if a computer could tell you if the milk was spoiled, if the medicine was the wrong kind, if the drinking water was toxic, if the CO2 level in the plane was too high?

The person who makes that battery or that computer program will do a lot of good for the world. The person who figures out how to do those things will build an economy. And not just for his or her own country – for other countries, too.

Everywhere we see a good economy and good education, we see great trading partners – and a safer global neighborhood. There’s a direct relationship between education, economy, governance and security.

The world’s leaders need to pick up the reins and lead. If you’re a business leader, your mission is not to guide your organization through the New Normal, but to grow it in the New Normal. In the old days, you might have gotten by with maintaining your market share, but those days are gone.

Hyper-interconnectedness means the world’s customers are your customers. We all know that a global marketplace is a difficult one to navigate. But we also know it’s bursting with opportunity. The more you do to encourage open societies, educated people, and mutually beneficial export systems, the more you help your own organization – and your country.

Key points

Our internal defense used to rely on the great oceans off our East and West coasts; but with new information technology that false sense of security is gone.

Poor people in developing countries see that the Western world, led by the USA, leads the pack in the consumption of more than its fair share of the world’s natural resources.

These days, every have-not person can see the people who have on any Internet-connected server.

War is a failure of politics. The day the U.S. invented and used the nuclear bomb was the day we could no longer afford to fail in politics.

0 notes

Text

What is GreenARMY?

Russel Honore’ leads GreenARMY, a network of civic, community, and environmental groups and concerned citizens from across Louisiana fighting for meaningful social, political, and environmental change in our state.

Lt. Gen. Honore’ (US Army-Retired) became involved in environmental issues when residents from Bayou Corne - frustrated by the lack of action in the wake of a devastating sinkhole - requested assistance. Honore’ recognized the barrage of pollution, climate, infrastructure and other issues facing Louisianans, from the levee board lawsuit to clean water, and he decided something needed to change.

youtube

GreenARMY is working in concert with its partners and allies to address environmental concerns across Louisiana, in our ground, our water and our air. These are just a few critical examples:

Coastal erosion and weather crises intensified by climate change - and their dire impact on our homes and our businesses