Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Seeing Is Loving

(art by @andrhomeda [please dont make me take this down for literally like,,, two calendar days its for a class final and no one will see it but you do great work thanks for being rad])

There is a unique sense of loss that comes from looking in the mirror and not seeing yourself. You don’t lose identity. That isn’t something the mirror could ever show you, and it doesn’t take being trans for someone to tell you that. Your personhood is not defined by your weight, your hair, your skin, your body. What we lose with our unrecognition, rather, is faith. Faith that we exist. We are told over and over again that seeing is believing. So who are we, if we cannot see who we know to be ourselves?

We are what others see.

Now you may be thinking, “Hey Casper, that sounds hella problematic, you’re really gonna go right out the gate with ‘we are what others see?’ What if I don’t express my gender in the same way as I identify. If someone looks butch to me, does that mean because I think they look a certain way they are then confined to that label of sexuality? What the hell?” And that would be fair. So I’ll take the time to answer some questions that will become really relevant here

What does it mean to be seen?

What does it mean to be known?

Technically these terms have very similar definitions. Both mean, in a sense, to perceive something or someone. One more visibly than the other, but as mentioned above, we always hear that seeing is believing, and then, what is believing if not knowing something to be true? To see something, to really see it, in the italicized and romanticized version of the word, is synonymous with knowing it. Think of a particularly bad argument with a friend or partner, or maybe just the last cheesy romantic comedy you saw. When we say we want to feel seen, or that we want to be heard, it really means we want to be known. To be fully understood.

A new definition: We are what others know us to be.

Physically seeing me, I am honestly not sure how most people process my appearance. I wrote, a while back, “I cannot tell if people see me as a boy or girl when they look at me anymore or if I just look small.” Of course, my personhood isn’t ‘small’, and my gender isn’t ‘small.’ But those who know me know who I am, and I can have faith in that being because they know it to exist.

Now, what does this mean in regards to gender and sexuality? I know that I exist because others know that I exist. In this sense, the ‘I’ can be swapped out for a multitude of other variables. For example, I know that I am male because others know me to be male. I know that my pansexuality exists because others know my pansexuality to exist. While I can know these things intrinsically, it is because others can react to them that I can be sure they exist. This is what it means to have a visible or social identity. Not that others need to see them in order for them to exist, but rather that if I spent my life existing in a darkened room by myself, there would be no reason for them, because I would simply be myself. In Imitation and Gender Insubordination, Judith Butler states that “gender is a kind of imitation for which there is no original” (Butler, 82). There are a thousand and one ways to unpack that quote. But to me, the idea is that gender is real and meaningful, but in isolation, it serves no purpose. We cannot have a concept of gender without an ingroup to imitate and an other to distance ourselves from. Alone, what would gender be, except another word for the being we know to be ourselves?

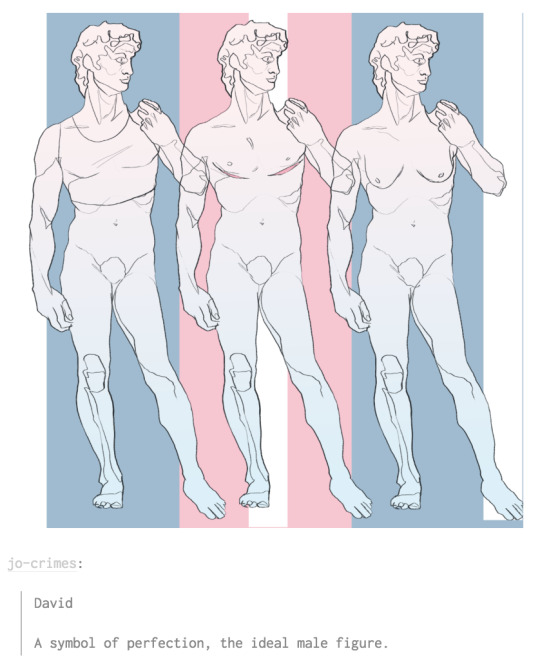

In Visible Identities: Race, Gender, and the Self, Linda Alcoff discussed the belief that “if race and gender could be divested of their purported visible attributes, they might be transformed to better reflect people’s subjective sense of themselves -- their actions, choices, their humanity -- rather than mere physical attributes that were accidents of birth” (Alcoff, 103). Alcoff goes on to argue that visible characteristics do serve a purpose, and in a sense, help define our own internal perceptions of identity as well. I don’t mean to argue against that, and I can only ever speak from my own personal experience (but what is academia, really, if not yelling your personal experience into the void as if it were universal?). But I don’t really see why the two things have to be mutually exclusive. Don’t we want, more than anything, to be able to be seen as the people we are? And is that inherently opposed to the body that we live in? In a world of ideals, wouldn’t our humanity be able to be seen at the same time as our physical being, in addition, as a part of, and entwined? If I reject my body as having been ‘born with the wrong one,’ aren’t I in a sense rejecting it as mine? If I am male and known by others to be male, is that not both my humanity and my form? I am both. I am all. To be seen as male is one thing. To be known as a whole ideal is another.

(art by @jo-crimes [hello yes please don’t make me take this down for like,,, two whole human days, your art is amazing and I really appreciate your work and am using it for a class assignment,,, you’re really doing the best thanks])

“And I am in love, still. And I am love, still. And I try to think of how all these things can exist at once. And I land on the answer. I am in multiple places at once. I refuse not to believe this is a superpower.” - Taliesin Grey, Encyclopedia

A new definition: We are the whole that others know us to be.

In class, we were asked to think about Alcoff’s idea of a horizon as “the individual or particular substantive perspective that each person has, that makes up who that person is, consisting of his or her background assumptions, form of life, and social location or position within the social structure and hierarchy” (Alcoff, 96). Essentially, our horizon is the view we have looking out on the world inherent to our position, just as reflective of who we are as it is of how we see the world. We were tasked to draw ourselves and our horizons. It was an easy premise. Make a stick figure of yourself and write the words looking out of how you perceive the world around you based on your identity. Students wrote family closest to their heads if that was important to them, put female in the distance if it didn’t have an impact on their lives, and layered race and sexuality in various forms depending on how it impacted their perception of themselves. All of our drawings looked different, because of course they did. We all see the skyline differently based on our perspective.

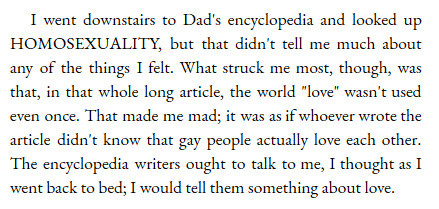

I sat and stared at mine for Far Too Long. I suddenly couldn’t think of how I ordered the puzzle pieces that became my being, all I knew was that when I zoomed out, they made a picture of me. I’d never identified enough with any of the labels I’d associated with myself to connect them with my personhood. I knew I was a poet because I loved poetry. I knew I was a son because I loved my mother. I knew I was a person capable of enormous love because I loved my partner. But I didn’t know what order it fell in, whether “poet” counted as an identity, and how I felt about the words that were used to describe the categories I fell into. I couldn’t think, suddenly, if there were any aspects of my identity that directly reflected my capability for love.

(Annie On My Mind by Nancy Garden)

I sat down and drew an elaborate picture of myself to buy time. Of how I saw myself. Of how others saw me. Of what others knew me to be. Of the whole that I am.

At the top of the page, the peak of my horizon, I scribbled “Casper” in yellow marker. My sun. Not just my name, but myself. I chose Casper for myself, as a title for the being I was, and the being I was in the midst of becoming, and the being I would continue to be. All I could think in the end was that, if nothing else, Casper was a marker of who I was as a whole. Of who I would be in a darkened room by myself just as much as who I am as a male in love with people of all genders. It was all that I was, in the fewest amount of syllables.

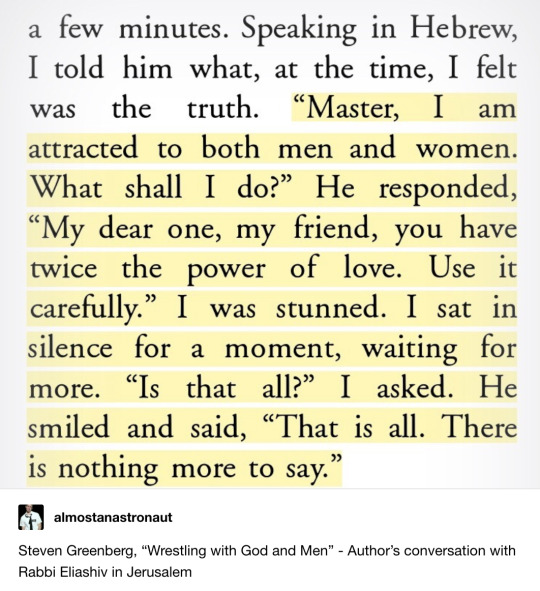

A final definition: On the edge of the horizon there is my name. That is all. There is nothing more to say.

2 notes

·

View notes