Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

“All that we are is the result of what we have thought.”

— Dhammapada

485 notes

·

View notes

Text

Una storia

Favour, sette anni, bimba nigeriana profuga arrivata in Italia su un gommone insieme alla sua famiglia. Conosco bene lei e la sua famiglia da ottobre 2017. Forse l'ho già detto, ma pro bono insegno italiano ai bambini e ragazzi profughi. Ne ho ascoltate tante di storie, ma questa in particolare ve la voglio raccontare perché l'ho vissuta sulla mia pelle e me l'ha scorticata. Superfluo dire che in questi mesi mi sono affezionata a queste persone a cui voglio bene?

Non solo una storia…

Favour vive insieme alla sua famiglia nella sua città, frequenta la scuola elementare con i suoi compagni di scuola. Tutte le mattine suo papà prima di andare al lavoro accompagna lei e la sua sorellina a scuola… Una routine di una qualunque bambina di quell'età.

Suo papà Laki ha seguito un percorso di studi, è diventato uno stimato imprenditore con una sua ditta. Conosce sua moglie di religione cattolica e si sposano con rito cattolico. Cominciano i primi dissapori tra le famiglie, ma loro si amano e da quell'unione nascono tre figli che vengono educati all'educazione cristiana, battezzati secondo il rito cristiano. Si arriva alla spaccatura familiare, non è comprensibile, accettabile per una famiglia musulmana tutto ciò. Cominciano le persecuzioni alla famiglia, vere e proprie minacce di morte. La religione che hanno scelto di seguire non va bene. Avvertimenti che consistono inizialmente nell'allontanamento forzato delle bambine dai genitori. Non solo avvertimenti. Un bel giorno picchiano a sangue la moglie. Il pestaggio le provoca gravi lesioni agli organi interni. Anche i suoi figli sono in pericolo.

Laki ha paura della sua stessa famiglia e decide di scappare.

Una promessa.

“Ti portiamo via e potrai ricominciare con tutta la tua famiglia lontano da qui…”

Per arrivare alla “salvezza” devono passare dalla Libia. In Libia Laki viene prelevato per un lungo mese, tenuto come in prigione, lasciato senza cibo e acqua per giorni e picchiato brutalmente tutti i giorni senza sapere nulla della sua famiglia.

Un ulteriore prezzo da pagare per la salvezza in attesa di conoscere il suo destino.

Una notte ci arrivano al gommone che li avrebbe portati lontani dalle paure, dalle minacce, verso dove non importava, ma lontano…

Una promessa non mantenuta.

Non tutti potete salire sulla stessa imbarcazione. Non si discute. La famiglia viene divisa. Favour sette anni e Persly quattro anni vengono strappate in lacrime dalla mamma e imbarcate con il papà. La mamma e il figlio maggiore in altra imbarcazione.

“Vi incontrerete tutti a destinazione…”

Così non è stato. In Italia sono arrivati solo Laki con le sue due bambine.

Viene mobilitata la Croce Rossa per cercare le centinaia di persone disperse. Si pensa al peggio. Per mesi non si è saputo nulla di tutte quelle persone. Uomini, donne, bambini.

Persone.

Laki ricomincia con questo immenso dolore la sua vita in Italia con le sue bambine.

Nuova scuola. Nuovo lavoro. Tutti i giorni Favour insieme alla sua sorellina viene accompagnata a scuola, con i suoi nuovi compagni, dal papà prima di andare al lavoro… Una routine di una bambina di quell'età, impaurita, spaesata spesso arrabbiata, che non conosce nessuno, non conosce la lingua, strappata dal suo paese e senza la mamma.

…Una storia come tante. Tutte queste persone hanno una storia da raccontare che li ha spinti a decidere di partire senza biglietto, senza destinazione verso una sperata salvezza. Verso un cambiamento.

La storia continua.

Oggi Laki vive con le sue due bambine in Italia. Lavora e sta studiando l'italiano. Un padre attento e premuroso. Nonostante tutto stanno andando avanti, già...nonostante tutto, nonostante le tante difficoltà stanno continuando la loro vita. Stanno seguendo tutti un difficile percorso psicologico per superare il lutto di una moglie, di una madre. Già…Meriah… Meriah in Italia non ci è mai arrivata. Il suo gommone è naufragato e tante persone sono state gettate in mare, tornando in Libia alleggerito. Meriah era tra queste… Il figlio maggiore ad oggi si nasconde a casa di uno zio della mamma in Libia, fatto credere di essere morto per non morire, perché tornare a casa vorrebbe dire essere trucidato dai suoi stessi familiari. Ad oggi il percorso per il ricongiungimento familiare è tutto a livello burocratico e ancora lungo.

Favour… questa è la sua storia. Per parlare di lei era doverosa la premessa. Era di lei che volevo raccontare. L'ho conosciuta per insegnarle l'italiano appena arrivata in Italia e adesso a scuola è una delle prime della classe. Una bimba che appena arrivata comunicava solo in inglese, diffidente e scontrosa e adesso parla correttamente la nostra lingua, corregge gli errori del papà e si fa voler bene e coccolare da tutti. Ci sarebbe tanto da raccontare di lei. Tante altre belle storie che ci hanno legate tanto in questi lunghi mesi. La sua tremenda paura dell'acqua da superare, il suo bel sorriso ritrovato a fatica, i pianti tra le mie braccia, le parole mai dette, quei terribili ricordi che l'hanno segnata e non riesce ad esternare. Laki che non riesce proprio a tenere a bada i capelli ribelli delle sue bimbe.

“Lo faceva Meriah…” Una mamma che non c'è più. I disegni di scuola da capire con le persone tutte colorate di rosa. Tanto il tempo che ho trascorso con queste persone che mi hanno permesso di conoscerle e condividere con loro il proprio vissuto.

Poi c'è un'altra storia...

Quella non serve raccontarla. È quella del Salvini che alza la voce, ma quella la conosciamo già bene tutti…

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hebrew Basics #1: All about the Hebrew Alphabet

In order to learn a language, the very first thing you need to know is reading it. This is a basic step in all language studies. Hopefully you’ll start conquering that by the end of this lesson :)

The Hebrew alphabet… isn’t an alphabet. Technically speaking, it’s an “‘abjad” (an acronym of the first four letters of the Arabic ‘abjad), although it is commonly called an alphabet (as I’ll continue calling it for simplicity’s sake). Characteristic of Semitic languages (to which Hebrew belongs, among Arabic and many others, extinct and alive), the ‘abjad’s main characteristic is (almost) complete lack of vowels. Every letter stands for a consonant, and vowels are simply omitted. It’s equivalent to writing English “lk ths.”

While using an ‘abjad-like system with English is quite hellish, the case for Hebrew is quite different. Due to its relatively simple vowel system and unique Semitic grammar and morphology (how words are formed and act in a sentence), using an ‘abjad is actually quite a reasonable choice for Hebrew. Oversimplifying, Hebrew words are comprised of a root and a template, each contribute meaning to the final word. The root is comprised of (usually three) consonants, and the template describes the vowels, prefixes and suffixes you insert between and around the consonants.

The Letters

The Hebrew alphabet, called הָאַלֶף־בֵּית/אָלֶפְבֵּית הָעִבְרִי ha’álef-bét ha’ivrí, is comprised of 22 letters.

The first, most important fact is that Hebrew is read from right to left.

Note: the names aren’t all that important to learning the letters. Simply learning their pronunciation is enough at this point.

Five of the letters, for historical reasons, have two different forms - a word-initial and -medial form, and a separate final form. These are marked with a 1 on the table.

As you might have noticed, some letters have multiple pronunciations, and some of these overlap with one another. This was caused by many changes that happened to the language’s phonology over the years since the alphabet was created (some 3,000 years ago in its earliest forms).

The most notable of these letters are the בֶּגֶ״ד כֶּפֶ״ת* béged kéfet letters, marked with a 2. These days, for historical reasons**, only three letters actually change their pronunciation depending on their position in a word–ב bet, כ kaf, פ pe–and they are the only ones marked on the list, pronounced as /b~v/, /k~kh/, /p~f/, respectively. Generally speaking, for native words, at the beginning of a word and directly after a consonant (with no vowel in-between), they are pronounced with their ‘hard’ pronunciation (/b/ /k/ /p/), and in all other positions with their ‘soft’ pronunciation (/v/ /kh/ /f/). Loanwords do not follow these rules, and are pronounced as they are in the original language.

*Acronyms and initialisms, as well as Hebrew letter names and numerals, are marked by the Hebrew punctuation mark ״, called גֵּרְשַׁיִם gershayim, and placed before the last letter of the phrase. It is similar looking to the Latin quotation mark, and is often confused with it even by native speakers, but nonetheless different.

**You might have noticed that ‘historically’, ‘for historical reasons’, etc. are somewhat a trend in this lesson. Hebrew is an incredibly old language, about 5,000 years old in fact, riddled with old tales and tradition. During that period it changed a lot, it even died for 2,000 years and came back to haunt us in the last 150. Despite this, the Hebrew writing system as we know it today was tailored (albeit not perfectly) for Hebrew as it was spoken some 2,500 years ago, and remained relatively unchanged during that whole period. Therefore, there are a lot of peculiarities in the Hebrew alphabet that we simply do not have time to cover, stemming from the complicated history of the language.

There are also a handful of letters which, for historical reasons, are still pronounced the same.

א alef + ע áyin (+ ה he) = ‘ (glottal stop) or none (ה he only as none)

soft ב bet + ו vav = /v/

ח chet + soft כ kaf = /ch/*

ט tet + ת tav = /t/

hard כ kaf + ק qof = /k/*

ס sámekh + שׂ sin = /s/

*I still transcribe hard כ kaf and ק qof, as well as ח chet and soft כ kaf differently (/k/ vs /q/, /ch/ vs /kh/) because, well, it’s easier than the other homophones.

To form a word, simply string together letters - the vowels magically appear in your head!

ספר (séfer) - book

ספר (sapár) - barber, hairdresser

ספר (sipér) - (he) told, (he) cut hair

ספר (supár) - (passive of above verb)

ספר (sper) - spare (English loanword)

…Yeah, that’s easier said than done.

See, in general with the ‘abjad system, all words pronounced with the same consonants are written exactly the same, which can create a heck of a lot of homographs, words written the same but pronounced differently. This problem has been cleverly solved using אִמּוֹת קְרִיאָה - ‘imót kri’á (literally mothers of reading). These are letters in Hebrew that serve a double function as a consonant and a vowel, marked with a 3 on the table. Noticed the letters ו vav and י yod have multiple pronunciations?

In many words, vowels (especially /i/, /o/ and /u/) are marked using one of these letters to reduce the number of homographs. For example, the words listed earlier are usually written:

ספר (séfer) - book

ספר (sapár) - barber, hairdresser

סיפר (sipér) - (he) told, (he) cut hair

סופר (supár) - (passive of above verb)

ספייר (sper) - spare (English loanword)

These letters can be conveniently memorized using the acronym אֶהֶוִ״י ‘eheví.

Interestingly enough, Yiddish, written with the same 22 letters, uses these letters (and some more) to create a full alphabet, where each and every vowel in a word is written, as well as the consonants. But we aren’t learning Yiddish here.

Learning when and where to put ‘imót kri’á comes with time, as it is often up to the reader where to put them. The style of writing I’ll be teaching with is called כְּתִיב חֲסֵר ktiv chasér, or ‘lacking spelling,’ where the bare minimum of ‘imót kri’á are used, and all vowels are indicated using vowel points, נִקּוּד niqúd, explained in the next section. This style is often used in children’s books and Biblical inscriptions; ktiv chasér is historically the only way Hebrew was written. This is in opposition to כְּתִיב מָלֵא ktiv malé, ‘full spelling,’ where ‘imót kri’á are used and vowel points aren’t; this is the style of writing virtually every modern Hebrew text is written in.

This might seem all confusing at this point, but let me assure you it isn’t. Once you wrap your head around it and start reading more and more of the language, you just instinctively know how a word is read off the bat. Context is usually more than enough to settle any ambiguities in how to read a word.

Vowel Points

Vowel points, נִקּוּד niqúd, are the diacritics used in Hebrew to indicate the vowels of a word, to complement the ambiguous ‘abjad system. These are the little dots and lines around each letter in previous examples.

Hebrew has five vowels: /a/ /e/ /i/ /o/ /u/ - pronounced almost identically to those in Spanish and Greek, to name a few. However, it has 13 different vowel points. Historically, and still in some traditional readings of the Bible, each mark had a different pronunciation, but in Modern Hebrew a lot of them merged with one another.

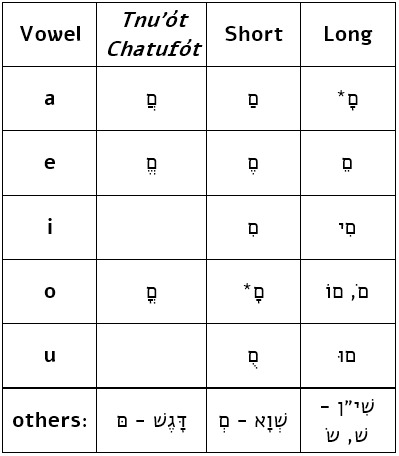

The final form of מ mem, ם, is used as a placeholder here.

Make no mistake, the two vowels marked with an asterisk are in fact the same vowel. For now, know that in most cases it is pronounces as /a/. The /o/ pronunciation is rare, only in certain templates of words, and distinguishing between them is out of the scope of this lesson. For now, the only common word that uses the /o/ pronunciation is כָּל kol, meaning ‘all’.

Short and long vowels are only traditional nomenclature - in practice, all vowels in each row are pronounced with the same length. תְּנוּעוֹת חֲטוּפוֹת tnu’ót chatufót are stlightly different, but nonetheless pronounced the same. Note that the some long vowels use ‘imót kri’á intrinsically.

דָּגֶשׁ Dagésh:

The point on the bottom left, the דָּגֶשׁ dagésh, is an interesting topic. However, the only relevant point to this lesson is that it distinguishes between hard (with dagesh) and soft (without) pronunciations of בֶּגֶ״ד כֶּפֶ״ת béged kéfet letters.

שְׁוָא Shva:

There are two types of shva: נַע na’ ‘moving’ - indicating an /e/, and נַח nach ‘still’ - indicating no vowel. Distinguishing between them is way out of the scope of this lesson, so for now the only way to tell them apart is through experience and transliterations.

שִׁי״ן Shin Points:

You might have noticed the rogue ש shin at the bottom of the table there. ש shin is different to other letters with double pronunciations, as it had always had two different pronunciations. Therefore, it got a different point to distinguish between the two: a dot on the right spoke of the ש shin indicates the common /sh/ pronunciation - שׁ, and a dot on the left spoke indicates the rarer /s/ pronunciation - שׂ. Each pronunciation is subsequently called שִׁי״ן יְמַנִית shin yemanít ‘right שִׁי״ן’ and שִׁי״ן שְֹמָאלִית shin smalít ‘left שִׁי״ן’.

All word-final letters have no vowel, unless marked otherwise. Most letters cannot even take a vowel mark at the end of a word. Exceptionally, ה he, ח chet, final ך kaf, ע áyin, ת tav, in certain circumstances do take vowel marks. ש shin must always have either a left or a right point, but no other vowel mark.

Practice!

Try reading these basic Hebrew words, then look at the answer key at the end to see if you were right.

1. אֲנִי 2. כֶּלֶב 3. בְּתוֹךְ 4. שֻׁלְחָן 5. פְּרִי 6. כָּל 7. יַם 8. עֵץ 9. אֲדָמָה 10. שְׂמֹאל

Answer Key

‘aní – I (me)

kélev – dog

betókh – inside

shulchán – table

pri – fruit

kol – all

yam – sea

‘ets – tree

‘adamá – ground, earth

smol – left (vs. right)

Alright then, that’s it for today! Follow me for more Hebrew lessons, hopefully they won’t all be as long as this one :D

לְהִתְרַאוֹת בַּפַּעַם הַבָּאָה! (lehitraót bapá’am haba’á)

See you next time!

743 notes

·

View notes

Text

Color and Language

Many people are surprised to learn that different languages do not consider the basic colors to be the same. Some New Guinea Highland languages, for example, still have terms only for black and white (perhaps better translated as “dark” and “light”). Hanuno'o language, spoken in the Philippines, has only four basic color words: black, white, red and green. Pirahã language, spoken by an Amazonian tribe, is said to have no fixed words for colors. According to linguist Dan Everett, if you show them a red cup, they’re likely to say, “This looks like blood”. Some languages have color distinctions which are, well, foreign to native English speakers:

Latin originally lacked a generic color word for “gray” and “brown” and had to borrow its words from Germanic language sources.

Biblical Hebrew had no word for blue.

Navajo has one word for both grey and brown and one for blue and green. It has two for black, however, distinguishing the color of “coal” from that of “darkness”.

Russian, Italian, and Greek have different basic words for darker and lighter shades of blue.

Hungarian has two different basic red words – bordó (darker reds) and piros (lighter reds.)

Shona language (a Bantu language from Southern Africa) has no one word for our “green” concept; they have one word for yellowish-green, and a different word for bluish-green.

Hindi has no standard word for the color “gray”. However, lists for child or foreigner Hindi language learning include “saffron” [केसर] as a basic color.

In Gaelic glas can mean both “grey” and “green”– glasbheinn is “green mountain”; glais-fheur is “green grass.”

7K notes

·

View notes

Text

“Esperar que el mundo te trate en forma justa porque eres una buena persona es lo mismo que esperar que un toro no te ataque porque eres vegetariano.”

— Fritz Perls

671 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Knowing how to be solitary is central to the art of loving. When we can be alone, we can be with others without using them as a means of escape.”

— bell hooks

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

“Do not undervalue attention. It means interest and also love. To know, to do, to discover, or to create you must give your heart to it – which means attention. All the blessings flow from it.”

— Sri Nisargadatta Maharaj

405 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Man, sometimes it takes you a long time to sound like yourself.

Miles Davis (via lazyyogi)

555 notes

·

View notes

Photo

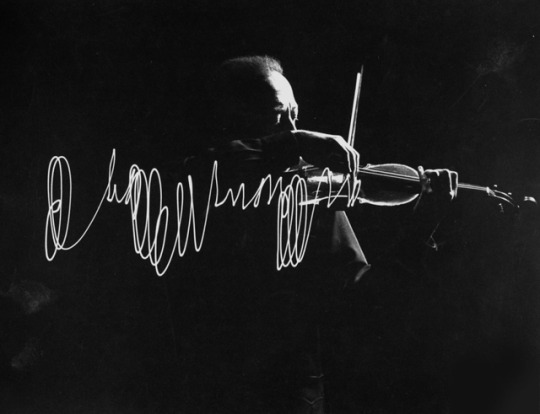

A time exposure of violinist Jascha Heifitz playing with a light attached to the end of his bow, photographed by Gjon Mili in New York, 1952

via reddit

1K notes

·

View notes

Quote

If you get tired learn to rest, not quit.

Unknown (via onlinecounsellingcollege)

7K notes

·

View notes

Video

instagram

“Don’t make eye contact, don’t make eye contact…”

58K notes

·

View notes

Quote

It’s dark because you are trying too hard. Lightly child, lightly. Learn to do everything lightly. Yes, feel lightly even though you’re feeling deeply. Just lightly let things happen and lightly cope with them. I was so preposterously serious in those days. Lightly, lightly – it’s the best advice ever given me…to throw away your baggage and go forward. There are quicksands all about you, sucking at your feet, trying to suck you down into fear and self-pity and despair. That’s why you must walk so lightly. Lightly my darling…

Aldous Huxley, Island (via themindmovement)

3K notes

·

View notes