Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Hey Rachel!

Great post. Your reflections on reconnecting children with nature really hit home. The image of David Suzuki’s childhood swamp turned shopping mall is such a stark reminder of how quickly those "magical" places can disappear. It reminded me of a patch of trees near my old neighbourhood where my friends and I would spend hours exploring. It wasn’t anything spectacular, just some trees and worn-down trails, but it felt like our own little world. Looking back, those kinds of spaces really do shape how we connect with nature.

I love that you’re heading into interpretation with a focus on inspiring kids and families. It’s easy to underestimate how powerful those small experiences can be, like flipping over a log and discovering a salamander or watching a chickadee land just a few feet away. Those moments stick with people. They plant the seeds of curiosity, and curiosity often grows into care.

I also appreciated your point about reconnecting parents with nature. Sometimes I wonder if we focus so much on "kids these days" that we forget their biggest role models are right there at home. Adults need those moments of awe just as much as kids do. Maybe even more.

As for your question, my biggest takeaway from this course has been the realization that interpretation isn’t about memorizing facts, it's about storytelling, connection, and creating those quiet, unforgettable moments where people feel part of something bigger than themselves. That's where the magic happens. Good luck at African Lion Safari, sounds like you'll be helping people discover some pretty amazing stories there!

Unit 10 - Environmental Sustainability and My Personal Ethic as a Nature Interpreter

For the final blog post of the semester, and of my entire undergraduate journey, I find myself incredibly grateful for this thought-provoking and deeply important prompt. It has provided me with an opportunity to reflect not just on this course, but on my entire four-year experience in Wildlife Biology & Conservation, and on the path ahead in my future career.

The video featuring David Suzuki and Richard Louv at the Art Gallery of Ontario, discussing how to reconnect with nature, was especially impactful. It deepened my understanding of my own relationship with the natural world and provided valuable insights that helped me address the prompts for this blog.

youtube

My Personal Ethic as I Develop as a Nature Interpreter

In their discussion, David Suzuki and Richard Louv spoke extensively about the relationship between children and nature, emphasizing how it has changed over the years. Suzuki shared memories of finding solace and inspiration in what he described as a "magical" swamp near his childhood home in London, Ontario. That special place has since been replaced by a shopping mall. He posed a powerful question: “I just wonder about our children and where they find the kind of inspiration that I did when I was a boy.”

Louv, referencing his book The Nature Principle, stated, “The more high-tech our lives become, the more nature we need.” This resonates deeply in an era where parents are frequently criticized for allowing children too much screen time. But Louv challenges this criticism by asking, “Then they would do what?” Modern neighborhoods often lack natural spaces where children can safely explore, and an overblown fear of strangers, fueled by over-dramatized media coverage, has led to parents sheltering their kids more than ever. As a result, many children today are missing out on the unstructured outdoor experiences that previous generations took for granted.

This issue is personal for me. My parents often reminisce about spending entire days outdoors, playing and exploring freely with their friends, only returning home when the streetlights came on. In contrast, my own childhood was far more restricted. I was rarely allowed to venture down the street alone, even with a phone for safety.

Louv emphasizes that environmentalists must remain focused on their responsibility to future generations. Children are the future policymakers, leaders, and stewards of our planet. If they grow up disconnected from nature, we risk further diminishing the priority given to environmental conservation.

Should it be access to a backyard garden, a walk, a trip to the beach, we need to make more of an effort to get kids out of the house, out from behind their screens, and outside, where they can connect with nature. It's not only important for their own health, but also for the future of society.

This realization defines my personal ethic as a nature interpreter. I see it as my responsibility to bridge the growing gap between children and the natural world. My role will involve creating meaningful experiences that foster a deep appreciation for nature in young minds. Beyond that, I hope to inspire parents to reconnect with the environment as well. To remind them of their own childhood adventures in nature and encourage them to pass those experiences on to their children.

Once you have the privilege of truly experiencing nature, developing a passion for it comes naturally. Today, the real challenge come in carving out time in our busy lives to venture out and immerse ourselves in the beauty of the natural world. And I think that's where we, as nature interpreters, come in to help.

The Beliefs I Bring

At my core, my beliefs have always been deeply rooted in nature. As human beings, we are biological creatures, yet we have become largely disconnected from the natural world that once defined our existence. Our planet is facing an environmental crisis, with countless species at risk, and I firmly believe that conservation should be one of our highest priorities.

In today’s scary political state, where environmental concerns often take a back seat to economic and political agendas, it is more important than ever to remain firm in our commitment to conservation. As environmentalists, we must continue to advocate for the protection of our natural world and inspire others to do the same.

What Can I Do?

This summer, I am happy to say that I will be working as a Nature Interpreter at African Lion Safari. I will be working with the parrot department, not only caring for the birds, but also informing guests about some of the most endangered groups of birds.

The path forward requires education, engagement, and action. Through my work as a nature interpreter, I hope to instill a sense of wonder and responsibility in the next generation. By helping people form personal connections with nature, we can form a society that values and prioritizes environmental stewardship.

Looking back on my undergraduate journey, I feel an immense sense of purpose. The lessons I have learned, the experiences I have gained, and the values I hold close will guide me as I step into my future career. I am eager to contribute to conservation efforts, to educate and inspire, and to help shape a world where nature is not just an afterthought but a fundamental part of our lives.

As I conclude this final blog post, I carry with me the knowledge that reconnecting with nature is not just a personal journey but a collective responsibility. It is a responsibility I am ready to embrace, and one that I hope to share with others for years to come.

A big thank you to the professor of this course, Amanda Hooykaas. This course has allowed for so much reflection, realization, and lessons about how to connect others with nature, that I will surely take with me throughout my career.

I hope that reading these blog posts allowed for as much personal reflection as they did for me writing them.

I am eager to hear from my classmates: What was the biggest takeaway from this course?

References

African Lion Safari. (n.d.). Parrots. Retrieved on March 19, 2025 from https://lionsafari.com/programmes/parrots/

Suzuki, D., & Louv, R. (2012, July 20). David Suzuki and Richard Louv at AGO [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=F5DI1Ffdl6Y

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hi Sophie,

I really enjoyed reading your blog! Your reflection on the power of storytelling and the need to make environmental education inclusive resonated deeply with me. I appreciate how you tied your personal experiences into your understanding of nature interpretation. It’s clear that your connection to the landscape has shaped your ethics in meaningful ways.

One aspect that really stood out to me was your emphasis on providing hope as an interpreter. I’ve been thinking a lot about how important it is to inspire people with a sense of possibility rather than overwhelm them with doom and gloom. Nature interpretation has this beautiful way of showing us that the earth is still filled with wonders, resilience, and opportunities for positive change. By sharing those moments of wonder—whether through a breathtaking sunset, a glimpse of wildlife, or a meaningful story—interpreters can help visitors feel empowered rather than discouraged.

I also appreciated your point about the value of hands-on experiences. I too believe when people are encouraged to engage with nature physically, whether that’s turning over a log, feeling the texture of bark, or even quietly sitting in one spot and observing, they build connections that can’t be forged by facts alone. Those moments feel real, memorable, and personal.

Your approach sounds thoughtful and intentional, and I’m sure your future students will thrive under your guidance. Thanks for sharing such an inspiring reflection; it’s given me a lot to think about as I continue to grow as an interpreter.

Cheers, Gil

The Final Post! My Personal Ethics and Growth as an Interpreter

Personal Ethics as an Interpreter

Reflecting on everything we have learned throughout this course, I see how my experiences, beliefs, and sense of urgency to promote profound connections between humans and the environment have greatly influenced my personal ethics. The goal of nature interpretation is to make people interested, inspired and, above all, foster respect for the natural world. Something that stuck with me is that it is not only about imparting facts but about listening to those around us and learning about what inspires them. Personal ethics are an individual's moral principles and values that guide their decisions and actions in both personal and professional life (Adams, 1989). This course has taught me that nature interpretation is not just about what is in front of us, but the deeper meaning of the things around us. Understanding this can help foster our decisions for the future. My ethics are closely connected with my relationship with nature. Being surrounded by the Niagara escarpment and Lake Ontario as a child gave me a deep appreciation for the natural world and a strong conviction in the value of conservation. Exploring nature is not only a fun hobby but also a necessary exercise for mental health. Spending time outside improves cognitive performance, lowers stress levels, and cultivates creativity. As a result, I support spending more time outside and developing an appreciation and respect for nature. I view nature as both a haven and a school, where I can learn countless lessons about resiliency, interconnectedness, and the beauty of the world around me.

Lake Ontario Sunset

The Beliefs I Bring

One of the first things I believe is that nature is an essential component of our identity and well-being, not something that exists outside of human existence. Neil Evernden's view that "we do not end at our fingertips" but rather expand throughout the landscape is in line with this concept (Rodenburg, 2019). My family went on many camping trips as kids, exploring lakes, and forests, which helped me develop an innate love of the natural world that transcended textbooks and organized classes. This helped shape my appreciation for nature as camping in a tent allows you to fully slow down and immerse yourself in nature, which is something I think is critical in today’s fast-paced society. We recently purchased a jetski and summers are spent at the lake exploring quarries, bays, and different parts of Lake Erie and Ontario. It allows me to explore new corners of the place I grew up in.

Our Camping Setup!

Another belief is that storytelling is one of the most effective means of promoting relationships with nature. Effective interpretation requires more than just communicating information, it must also uncover deeper meanings and linkages, as noted in the textbook (Beck, Cable & Knudson, 2018). I have seen firsthand how people are significantly more interested when listening to stories or ecological processes than in discrete scientific justifications. I want to make abstract environmental topics concrete and approachable by including narratives in my interpretative work. I think this course has helped me realize that. I want to be a High School Biology teacher, so I will take this knowledge with me and incorporate useful, practical examples and storytelling in my lesson plans to make my lessons more enjoyable and approachable for students.

Can anyone else feel themselves coming back to life now after such a long and harsh winter? The warm weather and sun the past few weeks have brightened my mood and got me excited for Spring! Something I strongly believe in and advocate for is Vitamin D. I believe it is amazing for our souls. Sunlight exposure elevates mood, increases creativity, and improves mental clarity. By lowering stress and promoting attention restoration, studies have demonstrated that exposure to nature, especially time spent in the sun, can enhance mental health and cognitive performance (Bratman, Hamilton, & Daily, 2012). For this reason, I stress the significance of seasonal changes and their effects on our inner selves as well as our interactions with the natural world. Spring serves as a reminder of rebirth, development, and the interdependence of all life, lessons that are central to my view of nature.

What Responsibilities do I have?

As noted by Jacob Rodenburg (2019), in the changing world, nature interpreters have a difficult job of educating those around us. This entails striking a balance between talking about issues like habitat degradation, biodiversity loss, and climate change and providing instances of successful conservation initiatives and workable solutions. Another responsibility is to incorporate the conversation of nature in social media engagements, gatherings, and informal chats. To ensure that people perceive themselves as active participants in environmental change rather than passive onlookers, I must serve as a link between knowledge and firsthand experience. I also believe I must teach kids about the natural world, climate change, and environmental interpretation when I become a teacher. I want to give young students a feeling of interest and care for the environment since they are very impressionable. I can assist students in gaining a greater understanding of the world around them by including experiential learning and nature-based teachings in my instruction. I also understand that being a good steward of nature is a prerequisite for becoming a nature interpreter. I have to set an example of sustainable behavior, promote conservation, and make sure that my personal behavior reflects the environmental principles I teach. By leading with integrity and passion, I hope to inspire the next generation to become responsible caretakers of the planet.

Group of Kids I camp counselled

Suitable Approaches for Me I think that experiential learning and interactive involvement work best for me because of my personality and communication style. As noted by Richard Louv in the lecture, it's important to provide kids with direct exposure to nature. I am currently a tutor and I place a strong emphasis on hands-on activities, as it helps students visualize and learn better. I can incorporate this in nature interpretation by planting plants, turning over logs to search for insects, or listening to bird sounds. In addition to improving learning, this tactile interaction helps people feel more connected to their surroundings. I also learned through this course that one of the best ways to learn is when we see ourselves as part of it. This aligns with the idea that "kids connect best to places through stories and faces" (Rodenburg, 2019). One way I feel connected to my community is by going for walks around Guelph, which allow me to ground myself, declutter my thoughts, and slow my mind. I get a true sensation of connection to nature in these brief moments.

Reflecting on the Future

Nature is continuously evolving, as is my knowledge. One of my biggest takeaways from this course has been the importance of fostering hope. Rodenburg (2019) states, "We can create nature-rich communities where kids feel a deep and abiding love for the living systems that we all are immersed in." This idea deeply resonates with me. Rather than focusing solely on preservation, it is important to restore ecosystems rather than just minimizing harm actively.

I also recognize that I must make environmental education inclusive and accessible as part of my privilege as an interpreter. It is easy to forget that not everybody grew up camping, traveling, or walking into their backyard and being surrounded by forest and nature. This leaves out vulnerable groups, who are frequently the ones most impacted by environmental deterioration. In the future, I hope to expand my interpretive practice to include other viewpoints, especially those related to Indigenous knowledge systems and community-based conservation initiatives.

To encourage others to view themselves as essential to the natural world, I will continue to create deep connections between people and the environment via storytelling, experiential learning, and education founded on hope. The goal of interpretation is to create experiences that are transformational, not only to transmit information. I know I am doing my job if I can inspire someone to take action and I am excited to apply my knowledge from this class to the real world.

It has been so fun to read everyone's blogs this semester, I have learned so much! I hope everyone is taking away something from this course just as I am!

Signing Out 🌲🌧☀️🦌

Sophie

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Unit 10: Cultivating Awe & Stewardship

The very first blog I wrote for this course began with a reflection on "the sublime", that overwhelming feeling of witnessing something far greater than yourself. As a child, I remember moments in nature that felt profound, where towering mountains, endless forests, or the hush of snowfall seemed to elicit a feeling that is beyond words. Those experiences stayed with me, shaping how I see the world. Now, as I develop as a nature interpreter, I want to help others, children and adults alike, find those moments for themselves. Whether it's standing beneath a vast sky or hearing the quiet rhythm of a forest, I believe those encounters with the sublime can change us in powerful ways.

Beliefs: The Power of Awe and Connection

I believe that awe is a powerful catalyst for positive change. As Keltner and Haidt (2003) observed, awe can "change the course of a life in profound and permanent ways." Encountering something vast and unexpected, a breathtaking landscape, a moving piece of art, or a remarkable feat, can expand our focus outward, reducing self-centeredness and inspiring kindness, cooperation, and generosity (Abrahamson, 2014). Experiences of awe can even promote physical and mental well-being, reducing stress and improving mood (Green & Keltner, 2017). This understanding reinforces my belief that awe must be central to my work as a nature interpreter.

I also believe that interpretation should spark curiosity and encourage thoughtful reflection. As Amanda Giracca (2016) stated, nature study is not just about memorizing facts but about "the opportunity to question and grow, to be moved, to be momentarily stunned, or flummoxed, by something you couldn't have anticipated." This belief drives my commitment to creating experiences that invite wonder, surprise, and deep thinking rather than just delivering information.

Picture I took atop Whistler Blackcomb Mountain, a view that left me stunned.

Finally, I believe in the power of community and shared responsibility. Awe, as Keltner (2016) noted, strengthens our sense of connection to others and encourages cooperation. By fostering this sense of interconnectedness, interpreters can inspire individuals to become stewards of both their environment and their cultural heritage.

Responsibilities: Inspiring Stewardship and Lifelong Learning

As a nature interpreter, I recognize my responsibility to inspire stewardship in others. Bixler and Joy (2016) emphasized the importance of "mentoring children and youth such that later, as young adults, they desire to participate in nature-dependent recreation on their own or even seek careers working in wild settings." Understanding this has strengthened my sense of responsibility to engage young people in meaningful outdoor experiences that plant the seeds for future stewardship.

Equally important is my responsibility to create interpretive experiences that invite all visitors to develop their own relationships with the natural world. Some moments of connection happen effortlessly, like watching the sunset illuminate the rock formations on the beach, while others may require guidance and encouragement. Whether through direct engagement or simply by providing space for reflection, I believe my role is to help visitors feel part of something larger than themselves.

Picture I took during sunset in Northern Bruce Peninsula (Tobermory, ON)

Additionally, I see it as my responsibility to continue learning and refining my craft. As Barry Lopez (2002) described, contemporary naturalists must be "scientifically grounded, politically attuned, field experienced, [and] library enriched." This holistic approach requires me to stay informed not only about ecological and cultural knowledge but also about the evolving social and political landscapes that shape our world. This responsibility is essential because, as Lopez noted, those who control firsthand knowledge shape societal narratives. As an interpreter, I have a responsibility to be a reliable and honest source of information, empowering visitors to think critically and make informed decisions about their relationship with the planet.

Approaches: Creating Meaningful Experiences

To uphold these beliefs and fulfill these responsibilities, I approach interpretation as both an art and a science. First, I strive to create opportunities for awe by inviting visitors to engage deeply with their surroundings. Sometimes this means using silence, allowing people to pause and absorb the sights, sounds, and sensations of a place without distraction. Other times, it may involve storytelling that brings a landscape or cultural site to life.

I also emphasize inquiry-based learning, encouraging visitors to ask questions, form hypotheses, and draw their own conclusions. This approach aligns with Giracca's (2016) view that nature study should encourage curiosity and wonder. Rather than presenting myself as an all-knowing expert, I aim to act as a guide, prompting reflection and dialogue that allows visitors to make personal connections with the places they explore.

Furthermore, I prioritize accessibility and inclusion in my interpretive work. Since awe and connection are deeply personal experiences, I strive to create programs that invite people of all backgrounds and abilities to engage with the natural world. This may involve adapting programs to meet the needs of different age groups, learning styles, or cultural perspectives. Lastly, I embrace a proactive and compassionate form of leadership as described in chapter 21 of the textbook. Interpretation must "exercise vigorous, proactive, and sensible leadership" that encourages individuals, communities, and nations to "consider their impact on the earth" while promoting solutions that foster thoughtful living. By inspiring both reflection and action, interpreters can guide society toward a more harmonious relationship with the planet.

Conclusion

My personal ethic as a nature interpreter centres on fostering awe, encouraging curiosity, and inspiring stewardship. By grounding my work in these values and drawing on the insights of experienced interpreters, psychologists, and environmental educators, I hope to create meaningful experiences that strengthen people's connections to the natural world. In doing so, I strive to promote a future where individuals, communities, and entire nations embrace thoughtful living, environmental responsibility, and respect for diverse cultural traditions. By guiding others to see their place within the broader web of life, I believe interpreters can help build a society rooted in generosity, cooperation, and deep reverence for the world we share.

(Sobel, 2019)

References

Larry Beck, Ted T. Cable, Douglas M. Knudson (2019, April 25): Interpreting Cultural and Natural Heritage: For a Better World. (n.d.). Retrieved March 21, 2025, from https://sagamore.vitalsource.com/reader/books/9781571678669/pageid/184

Sobel, D. T. (2019, December 13). A Return to Nature-Based Education. YES! Magazine. https://www.yesmagazine.org/environment/2019/12/13/nature-based-education

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hi Serena,

I really enjoyed reading your post, and I admire the profound way you captured the interconnectedness of nature and human society. The way you described teamwork as "the most amazing thing nature has to offer" feels incredibly true and essential. From ants to bees to humans in cities, your examples beautifully illustrate how collective effort is a fundamental force that sustains life.

Your reflection on the skills we risk losing like empathy, connection, and agency, struck me deeply. In a world increasingly dominated by technology, it's easy to become distanced from the very connections that have helped humanity thrive. I agree that fostering nature connection can help restore these essential skills. There’s something powerful about observing the intricate cooperation in an ecosystem, a reminder that individual contributions matter, no matter how small.

I especially appreciated your question: What do you want to do to contribute to the system? This is such an important reminder that we all have agency in shaping the world around us. For me, I believe my contribution lies in caring for and loving others while striving to be the best version of myself. This reflection is often overwhelming and jarring—questioning who I am, what I represent, and how those qualities impact the people and world around me. Yet, in those moments of self-reflection, I remind myself that I am someone who actively works to appreciate myself for who I am. That sense of self-acceptance, in turn, radiates outward, influencing how I connect with the people I love, those I care for, and even the natural world. Embracing this role brings a sense of purpose and reminds me that kindness, both inward and outward, contributes to the broader system in meaningful ways.

Thank you for your insightful words. You've encouraged me to reflect on how I can better contribute to the web of connections that sustains us all!

The Power of Teamwork (Unit 9)

You see it everywhere: outside, on the sidewalk, tiny little ants walk in a line, carrying breadcrumbs back to their nest. Bees buzz around the flowers, intent on gathering nectar to take back to their hive. You even see it in the skyscrapers rising up into the clouds, the organized roads and streets that take you where you want to go, and the people you collaborate with every day to get things done.

(Video: bees bustling around on a hive. Taken by Serena Causton)

(Photo: Toronto skyline as sunset against clouds. Taken by Sequoia Death)

The most amazing thing that nature has to offer is teamwork. Species of all shapes and sizes work together to create something greater than the sum of its parts. Humans create technology, spaceships, medicine, buildings, and more, together. Bees create hives they fill with honey. Ants create a network of tunnels to house the colony. Species everywhere create a system; a system that functions independently of the individuals that created it (Meadows, 2008). If one individual is lost, the system remains.

Monarch butterflies even use transgenerational teamwork; one generation begins the migration south to find somewhere warm to overwinter. Then the next generation is born in the south, and makes the return journey north (US Forest Service, 2024). This journey is guided by instinctive genetic patterns.

Unfortunately, it’s easy for humans to overlook the importance of these connections within a system when we get lost in the technology created by it (Beck et al., 2018; pg 468). Nicolas Carr (2014) warns that

“the mounting evidence of an erosion of skills, a dulling of perceptions, and a slowing of reactions should give us all pause.”

Interspecies cooperation is everywhere in nature, from ants to bees to birds to dolphins to elephants; this quality, preserved through millions of years of evolution, is clearly essential. These skills that we are losing, the skills of empathy, connection, and agency, were cultivated in our species for a reason; throughout our evolutionary history, these skills have made us stronger, better, and better adapted to survival.

What happens to us if we lose these skills?

Are we devolving? We as a society need to take proactive, intentional measures to connect with each other and strengthen our bonds.

As nature interpreters, we can strengthen these skills in ourselves and in others through promoting and supporting nature connection. Through nature, we can inspire awe, and awe can inspire action (Beck et al., 2018; pg 472). By being in nature we can also reduce reliance and dependence on technology, which can reduce the distractions that prevent people from connecting with each other, nature, and themselves.

Next time you go outside, whether in the city or in a forest, in a suburb or next to the ocean, think about everything you see around you. The birds you hear calling to each other from the trees. The squirrels running up and down the trunks, working hard to scavenge for acorns. The worms in the ground that filter soil and nutrients, turning chemicals into compounds that plants can eat. The plants that take up carbon dioxide and release oxygen for us to breathe.

(Photo: Centennial Park at sunset in 2018. Taken by Serena Causton). In this photo, the moss was disrupted on the right hand side by a mother duck and her ducklings swimming across the pond.

If you’re in an urban environment, think about the number of people who worked hard to mix and pour cement for the sidewalk. The people who measured and remeasured and mixed and remixed ratios until they found the perfect combination to even make cement. Think about the architects that designed the buildings you see, the mathematicians and engineers that made it possible, the construction workers that operated the equipment and machinery to build it, the transport workers who travelled across the country with materials to build.

(Photo: A night market in Osaka, 2024. Taken by Serena Causton)

Think about all these things that contribute to the system that makes life possible, whether it be natural or human-made. What role do you play in the system? Do you like your role?

What do you want to do to contribute to the system?

References:

Beck, L., Cable, T. T., & Knudson, D. M. (2018). Interpreting cultural and natural heritage: For A Better World. SAGAMORE Publishing, Sagamore Venture.

Meadows, D. H. (2008). Thinking in systems (Illustrated edition). Chelsea Green Publishing.

U.S. FOREST SERVICE. (2024). Monarch Butterfly Migration and Overwintering. Www.fs.usda.gov.https://www.fs.usda.gov/wildflowers/pollinators/Monarch_Butterfly/migration/index.shtml

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Unit 9: Earth's Biggest, Oldest, and Most Mysterious Tree

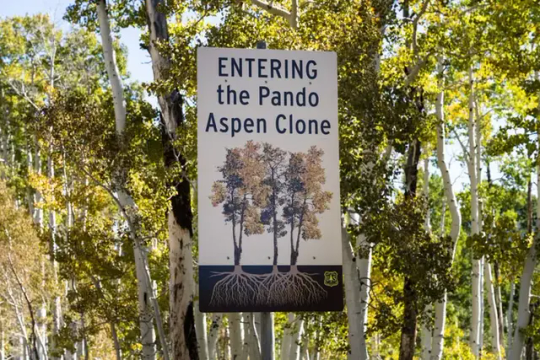

Imagine walking through a peaceful forest in Utah's Fishlake National Forest—golden leaves fluttering, sunlight flickering between slender trunks. You breathe in the crisp mountain air, feeling miles away from civilization. But here's the mind-blowing part: every single tree around you is actually the same organism.

Meet Pando, the Trembling Giant, a forest-sized tree that's been quietly thriving for thousands of years. This botanical marvel isn’t just big—it’s the biggest living thing on Earth by weight and area. Stretching across 106 acres with an estimated 47,000 identical tree trunks, Pando weighs over 6,600 tons.

At first glance, Pando looks like a typical aspen grove. But beneath the surface lies a sprawling network of interconnected roots—one single organism sending up thousands of identical stems. These trunks are like fingers on the same hand, each sprouting from a mighty, ancient root system. While individual stems live about 100-130 years before dying off and being replaced, Pando's root system is a time traveler from the distant past. Some estimates suggest Pando could be as old as 16,000 years! This tree was alive before the pyramids were built, before written language, before entire civilizations rose and fell. The exact age of the root system is difficult to calculate, but it is estimated to have started at the end of the last ice age.

Each stem is genetically identical (Strong, 2023).

Pando's species, the Quaking Aspen (Populus tremuloides), gets its name from its leaves' mesmerizing shimmer. Even the slightest breeze sends them trembling, or quaking, turning sunlight into a golden dance across the forest floor. It's like nature's version of a disco ball, and in the fall, Pando glows with vibrant gold that feels almost otherworldly.

But despite its ancient resilience, Pando faces a modern crisis. Pando is dying. Disease, blight, climate change, and wildfire suppression have all taken their toll on Pando, but the root cause of decline is a surprising one: too many herbivores, namely mule deer. The deer feast on the aspen, eating away the young before they can mature. Overgrazing by mule deer and elk has stopped new trunks from sprouting. Without fresh growth, this massive organism is slowly dying at the edges. Conservationists are racing to protect it, building fences to shield young shoots and studying ways to support its natural regeneration.

Scientists enclosed a section of Pando's forest with a protective fence to test its effectiveness against overgrazing. The fenced area is showing signs of recovery (Ketcham, 2018).

Pando’s story isn’t just about survival; it’s about endurance. This sprawling giant has weathered ice ages, droughts, and wildfires. Yet now, it's the quiet pressures of modern life that threaten to unravel this ancient being. Each trunk thrives because it's part of something larger. Just like in a healthy forest (or a healthy society), the strength of the whole depends on the well-being of every part.

Visiting Pando isn’t just a chance to witness a natural wonder; it’s an opportunity to see the forest through a different lens. Tourism plays a vital role in this. As our textbook suggests, incorporating an interpretative approach can deepen the experience, revealing layers of meaning that even locals may overlook. When done thoughtfully, tourism not only educates visitors but also fosters a sense of connection and responsibility. This kind of engagement can directly support conservation efforts by raising awareness and funding for protected areas like Fishlake National Forest. In this way, tourism becomes more than just sightseeing—it becomes a force for preserving landscapes and the stories they hold. If I ever find myself in central Utah, I would definitely make time to visit Fishlake National Forest and walk among the Trembling Giant. Fall is the best season, when Pando’s golden leaves create a shimmering canopy unlike anything else on Earth.

References

Christou, S. (2017, October 19) Pando —The Largest Living Organism in the World. Nova https://www.novausawood.com/pando-largest-living-organism

Ketcham, C. (2018, October 18). The Life and Death of Pando. Discover Magazine. https://www.discovermagazine.com/planet-earth/the-life-and-death-of-pando

Strong, R. (2023, June 6). Hydrophone recordings of Pando tree root system. Business Insider. https://www.businessinsider.com/hydrophone-recordings-of-pando-tree-root-system-2023-5

Gardner, J. (2021, February 3). Pando - The Trembling Giant. Pando Coffee. https://pandocoffee.com/blogs/news/pando-the-trembling-giant

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hey Kayla!

Your perspective on music’s deep roots in nature is both eye-opening and thought-provoking. It’s fascinating how we as humans instinctively tie music to different things, whether it be our devices/technology, instruments, or nature! I think you really nailed it on the head with the idea that although human music is human creation, in reality, rhythm, melody, and even structured patterns of sound existed long before we did. The idea that whales and birds compose their own “songs,” not just as calls but as something akin to structured music, adds a whole new dimension to what we define as musicality. You have truly made me wonder: have we been inspired by nature’s music all along but just failed to recognize it as such?

Your realization about using music as a memory tool struck a chord with me (pun intended). It’s almost as if nature taught us this trick, yet we rarely acknowledge it. Perhaps, as you suggest, incorporating music into interpretation or education could unlock a deeper, more instinctual way for people to learn. After all, if birds and whales can recognize musical patterns, it must be ingrained in something far more primal than we assume. And your story about Scotland, what a perfect way to illustrate the way music and place intertwine. It’s incredible how a song can transport us instantly, tying itself to a moment in time so seamlessly that it becomes part of the memory itself.

Thank you for sharing!

Blog Post 07: Music & Nature

When I think about music, what immediately comes to mind is Spotify, the radio, singing, and instruments. Arguably, I would think that is what would come to mind for the majority of people. Even though I love and enjoy nature in every form, and consider myself knowledgeable about many aspects of it, I do not typically connect it to my own idea of music.

We always end up associating the creation, production, and performance of music with humans, and our species. In fact, I decided to search up ‘music in nature’ and ‘nature in music’ on Google out of curiosity. Funny enough, the majority of pictures that showed up were people sitting in nature, singing, with a guitar, or wearing headphones. Why is it that we associate music with people? What about other species, or the sounds that parts of landscapes create themselves? Well, what if I told you that some of the core aspects, that rhymes and the ideas of using musical instruments, comes from animals? Species that predate us by millions of years use these same elements (Gray et al, 2001). In fact, “The ability to memorize and recognize musical patterns is also central to whale and bird music-making” (Gray et al, 2001). This makes me think of how often music is used for memorization, such as songs about places in the world or numbers or names. When I want to retain information, I find it easier to remember by making up a song for it. Did I learn this from nature? How can this contribute to my role as an interpreter? I subconsciously use music and rhymes for my own memorization, yet I have never thought about using it as a way to teach others, especially if it is new or complex information that could be harder to retain.

To end off this blog post, I want to share a song that takes me back to a natural landscape. As I have mentioned here before, I had the privilege of being able to study abroad last year. Somehow, this increased my love for nature even more, because I was able to see its beauty in new ways, in many different places. One of those places was Scotland, where I decided to do a solo weekend trip to see the Scottish Highlands. I was in a bus full of groups of people, and as the only individual of the party, I was put in the single seat next to the bus driver. At first I did not know how to feel about this, but I left feeling extremely grateful for it. I could immediately tell the driver had a love for what he did, and he had an entire playlist curated for the trip. As I sat next to him, I could see the connection he made to each song and what was in front of us. A particular song he played stuck out to me, titled The Glen by Beluga Lagoon. Every time I hear it, it takes me back to beautiful rolling mountains, and the sense of place and peace I felt on the trip.

Gray, P. M., Krause, B., Atema, J., Payne, R., Krumhansl, C., & Baptista, L. (2001). The music of nature and the nature of music. Science.

A picture I took on my visit to the Scottish Highlands, listening to The Glen by Beluga Lagoon

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Unit 7: Music in Nature & Nature in Music

Personally, I believe music and nature have always been intertwined, each reflecting and amplifying the other. Just as music is present in nature, nature also finds its way into human music, shaping melodies, rhythms, and even the instruments we play. Reflecting on what music in nature could entail, birdsong is the first thing that comes to mind. Birdsong, the long, often complex learned vocalizations birds produce, is a universally recognized form of “natural music”. Many species, such as the nightingale or the song sparrow, produce intricate and deliberate patterns of notes that serve as communication, territory marking, or even mate attraction. Scientists have studied the phrasing and repetition in birdsong, drawing parallels to human musical composition. Beyond individual sounds of birds, entire ecosystems create layered soundscapes. A tropical rainforest hums with insects, distant howls, and flowing water, creating an orchestra of rhythm. The desert, though seemingly quiet, reveals its own melody in the eerie whistle of the wind over dunes or the sudden, percussive sound of shifting sand.

Human music rather, has always been inspired by nature. Many traditional songs and compositions mimic the calls of birds, the roll of thunder, or the movement of water. Composers like Vivaldi, with The Four Seasons, and Beethoven, with his Pastoral Symphony, sought to capture the essence of natural landscapes in their work. Folk music across cultures often draws directly from the environment, for example, the sounds from a didgeridoo are meant to echo the sounds of the vast Australian outback. Modern music continues to incorporate nature, both literally and figuratively. Field recordings of rain, waves, or rustling trees are frequently used in ambient and electronic music. Even the instruments we use, from wooden flutes to hollowed-out drums, originate from natural materials, reminding us that music and nature are inseparable.

As for a song that takes me immediately back to a natural landscape, it has to be California Dreamin' by The Mamas and The Papas. Although I've never actually been to California, California Dreamin' evokes a deep sense of nostalgia and imagination for me. I heard it often when I was younger as part of movie soundtracks, on the internet, out loud through the house, or from the car speakers on long drives. The song has always painted a vivid picture in my mind of what California not only looks like, but how it could make a person feel. It painted this picture in my brain that California is an enchanting place of warmth and golden light. The lyrics coupled with the melody and harmonies of each artist’s voices built this image of a dreamscape place filled with sunlight, blue skies, rolling hills and a sense of calm and safety, allowing the imagination of what California looks like to roam freely. To me, the song California Dreamin’ serves as nature interpretation through music, transforming sound into a sensory journey that captures the beauty and essence of a place I’ve never been to.

References

Earth Day: How Mother Nature Inspired Four Major Composers | WQXR Features. (2015, April 21). WQXR. https://www.wqxr.org/story/earth-day-how-nature-inspired-major-composers

Starling, M. (2023, June 6). It Rocks in the Tree Tops, but Is That Bird Making Music? The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/06/06/science/birdsong-music.html

Cbsn. com staff Cbsn. com. (2001, March 1). Instrument Of The Outback—CBS News. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/instrument-of-the-outback/

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hi Ekaum, I love your take on this week's prompt!

Your reflection highlights an important and often overlooked reality: the artificial divide between STEM and the humanities. Dismissing one in favour of the other weakens our ability to approach problems holistically. The most pressing challenges of our time will always require both technical expertise and a deep understanding of human behaviour, history, and ethics.

Hyams’ train station analogy serves as a powerful reminder that history, philosophy, and the arts are not relics of the past but active forces shaping the present. The same is true in STEM. Scientific advancements don’t occur in a vacuum; they build upon historical knowledge and cultural context. For example, medical ethics is deeply informed by history, ignoring past medical injustices would lead to repeating them. Similarly, technological development without ethical reflection can lead to unintended consequences, as seen in debates about data privacy and AI usage.

Your mention of Indigenous environmental knowledge is another crucial point. Many STEM fields, particularly environmental science, benefit from historical and cultural insights that have been preserved outside of Western science. Traditional ecological knowledge, for instance, offers sustainable practices that modern science is only beginning to appreciate.

Rather than seeing STEM and the humanities as opposing forces, we should embrace their interconnection. True progress comes from understanding both where we’ve been and where we’re going because, as Hyams suggests, the past is never truly behind us.

Unpacking the Railway Station of Life

As I mentioned in my last blog post, I am a student in the Bachelor of Arts and Sciences program. This entails the fact that I am not only a student in STEM, rather I am also studying topics in the arts and humanities. As a result of this, I also frequently converse with students in both fields of study, and I get to learn and understand the perspectives of two vastly different types of individuals. One thing is for sure, I have made note of several occasions where my STEM friends belittle and make a mockery of those who are in non-STEM fields of study; topics such as family relations and human development, history, english, creative writing, and more. Belittling the humanities assumes that only technical knowledge has some sort of merit. Denying creativity and critical thinking the right to be considered “worthy” in debates of education suggests that understanding and thoroughly evaluating based on the knowledge of those who came before us is irrelevant, once we move beyond that moment in time.

Edward Hyams’ quote from The Gifts of Interpretation explores the importance of historical awareness in all methods of maintaining integrity. He argues that the value associated with history comes with the application and maintenance of connections which have been made in the past, that can continue to be made in the future. The past is what allows us to progress in the future, and we must acknowledge it in order to maintain integrity. The relevance of the experiences and important events which have happened yesterday are mandatory in order to not repeat the same mistakes tomorrow.

Hyams’ analogy of the train station beautifully conveys the message of his idea, considerably in a time as such we exist in today. It is easy to pretend that history is “of the past,” however those who were truly affected continue to be visited by that same train on a regular basis. In order to truly understand our world, historical and critical knowledge must be accessed with high degrees of respect and understanding. Some STEM students I have run into in my university career (and to be honest, even outside of schooling!) argue that because they focus on events that have already happened, humanities are irrelevant; the same way Hyams’ analogy believes that a railway station is meaningless once the train has passed through. What this perspective fails to acknowledge, however, is that history, philosophy, and the arts continue to inform and facilitate critical thinking and interpretation (which, in turn, is also highly relevant to scientific thoughts as well).

When STEM majors dismiss and belittle the humanities, they fail to recognize the interconnection of disciplines and history, and how they relate to the way we interpret the world today. Even environmental scientists can sometimes overlook the historical interpretations of nature that Indigenous groups may have maintained. To interpret nature meaningfully, we must acknowledge the full picture. The wisdom accumulated through every stop of the train at the railway station is what shapes our perception of the world, moreover how we plan to move forward in it.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Unit 6: Interpretation in Keeping Memory Alive

Edward Hyams’ words challenge us to reconsider our relationship with the past. He suggests that integrity is about keeping a story intact, ensuring that its pieces remain connected rather than forgotten. Without a conscious effort to remember, history risks becoming fragmented, leaving us with only disjointed glimpses of what once was. The past does not vanish simply because we have moved forward; it continues to exist, shaping our present whether we acknowledge it or not. To ignore history is like assuming a landmark vanishes the moment we leave it behind. It is still there, holding meaning, waiting for those who seek to understand it.

This perspective aligns with chapter 15 of our textbook, which emphasizes the role of interpretation in bringing past events, artifacts, and architecture to life. Historical interpretation is not passive; it actively shapes identity, values, and community. When interpreters weave historical narratives into engaging, thought-provoking experiences, they provide audiences with a deeper understanding of their place in the world. History, in this sense, is not a relic of the past but a living force that continues to shape our present and future.

One of the primary benefits of historical interpretation is its ability to foster a strong personal and collective identity. As individuals engage with stories of past struggles, triumphs, and transformations, they develop a sense of belonging and purpose. Communities thrive when their histories are acknowledged and shared, reinforcing collective memory and strengthening social bonds. A city with well-preserved and interpreted history is more than just a location—it becomes a meaningful home, enriched with stories that give depth to its streets, buildings, culture, and traditions.

A real example that beautifully expresses my above points is the immersive open-air museum Pioneer Village in Toronto. Visiting as a child on a school field trip was an unforgettable experience, truly the first time I felt like I had stepped into a different time period. The village is so well preserved and carefully maintained, aiming to breathe life into the past and share it with the community. Spaces like Pioneer Village provide a tangible, immersive way to experience history, making it feel real and relevant rather than a distant memory. Pioneer Village provides a setting where visitors can actively engage with history through interactive exhibits, costumed interpreters, and preserved buildings. The experience of walking through the village, seeing how people lived, worked, and interacted in the 1860s, made history feel tangible and alive. Skilled interpreters bring the past to life through compelling storytelling of the landmarks, foods, smells, demonstrations, etc., making historical events accessible and relevant to both younger and older audiences.

This active engagement with history can lead to transformative experiences and inspire new ways of thinking. When individuals see themselves reflected in historical narratives, whether through the resilience of their ancestors, the lessons drawn from past mistakes, or learning about how people lived in the 1800s where we live today, they gain a deeper understanding of their role in shaping both the present and the future

A historical interpreter in action at the Pioneer Village in Toronto!

Photo retrived from: Black Creek Pioneer Village—Step into 1860s Ontario. (n.d.). Retrieved February 12, 2025, from https://blackcreek.ca/

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hi Sara,

I really enjoyed reading your post and the GIF of the moonwalking bird!

You make compelling points about Washington Wachira’s contributions to citizen science and how the imagery in Dancing with the Birds serves as a powerful tool for inspiring public engagement in science and environmentalism! Both of these works, one shared through a TED Talk, the other through a documentary, made me realize truly how powerful storytelling is. While data collection is essential, it’s the stories we build around that data that truly inspire action. Science isn’t just about numbers and observations; it’s about understanding our place in nature, and stories help translate complex information into something deeply personal and memorable.

Information in today's society is no longer confined to academic papers or nature documentaries—it spreads through short videos, personal blog posts, and viral social media campaigns, reaching audiences far beyond traditional scientific communities. Platforms like Instagram, TikTok, and YouTube have transformed how we interact with nature. A single video of a rare bird sighting or a time-lapse of a blooming flower can spark curiosity and encourage thousands of people to learn more, contribute their own observations, or even take part in conservation efforts. Scientists and citizen scientists alike are using these platforms to share discoveries in real time, making science more interactive and participatory.

When science is presented in a way that is visually compelling and emotionally resonant, it becomes more than just information; it becomes an invitation to explore, connect, and take meaningful action on the most pressing issues.

Unit 5- Citizen Scientists and Creativity

Science is often viewed as the domain of experts—locked away in research labs, academic journals, and institutions. However, the rise of citizen science is proving that anyone with curiosity and a willingness to learn can contribute meaningfully to scientific discovery. Making science accessible empowers communities, enriches our understanding of the natural world, and fosters a deeper appreciation for conservation efforts.

A fantastic example of this is Washington Wachira, a wildlife ecologist, nature photographer, and safari guide whose passion for birds has inspired many. In his TED Talk, Wachira highlights the importance of bird databases in Africa and how technology is bridging the gap between scientists and the public. His work showcases how everyday people, equipped with nothing more than a smartphone, can contribute valuable data to ornithological research.

For many, computers are a luxury. However, as smartphones become increasingly common, apps are providing a more accessible way to engage with science. Whether it’s using apps like eBird or iNaturalist to document bird sightings, or participating in conservation programs through mobile platforms, technology is revolutionizing how people interact with the natural world. This accessibility ensures that more voices, especially from underrepresented regions, are included in global scientific discussions.

Wachira’s enthusiasm for birds is infectious, bringing to mind one of the first nature documentaries I ever watched—Netflix's Dancing with the Birds (2019). This film masterfully captures some of the world’s most extraordinary birds—particularly the birds of paradise—and showcases their mesmerizing mating rituals. The stunning visuals of these creatures in New Guinea’s untouched forests make a compelling case for preserving such fragile ecosystems. To me, this documentary represents a beautiful intersection of science and art—two powerful lenses through which we can interpret and appreciate nature. This fusion not only bridges the gap between scientific inquiry and artistic expression but also strengthens outreach, engaging both the scientific and creative communities in a more profound way.

The importance of citizen science in environmental education is well-documented. In their article Evaluating Environmental Education, Citizen Science, and Stewardship through Naturalist Programs, Merenlender and colleagues explore how hands-on participation in science fosters environmental stewardship. The study emphasizes that engaging people in nature-based learning experiences leads to stronger conservation efforts and a deeper connection with the environment. When individuals actively contribute to scientific research—whether by tracking bird migrations, monitoring water quality, or identifying plant species—they develop a personal stake in environmental issues.

Citizen science breaks down barriers to knowledge. It transforms people from passive consumers of information into active participants in discovery. By increasing access to scientific tools and data, we empower communities to take an active role in conservation. Washington Wachira’s work, the stunning imagery of Dancing With The Birds, and the research on environmental education all point to one truth: science belongs to everyone. The more accessible we make it, the more we all benefit—from individual learners to entire ecosystems.

This male Red-Capped Manakin snaps its wings and performs the lively "moonwalk" on a branch to attract a female's attention. This is one of many birds highlighted in Netflix's Documentary Dancing with The Birds- I highly recommend!

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Unit 5: How NYC’s Scaffolding Blocks Green Initiatives

For much of my education, science education (SE) focused on understanding concepts, while environmental education (EE), which emphasizes engagement and behaviour change, felt separate—often limited to extracurriculars, clubs, or field trips. This divide between knowledge and action felt like a missed opportunity. Now, in my fourth year of university, I noticed a shift in learning—from traditional classrooms to ones that included calls to action. Last semester, I took a course called Integrative Problems in Biological Science, where I explored biological issues and how an integrative approach could help solve them. I was tasked with identifying a specific problem within a larger biological issue, developing a solution, and pitching it for funding. One issue that stuck with me during the course was the ubiquity of NYC scaffolding and how it significantly hinders efforts to incorporate nature into daily life and creates obstacles for pollinators.

For every green space in NYC, there’s a looming obstacle: scaffolding. The city’s endless construction projects result in a near-constant presence of metal frames and tarps, wrapping around buildings and sidewalks, blocking sunlight, and limiting access to vital outdoor spaces. While scaffolding is essential for safety and urban renewal, it also creates an often-overlooked challenge for city people trying to integrate nature into their lives. For those looking to support pollinators, grow food, or simply add a bit more greenery to their surroundings, scaffolding can be a frustrating barrier—literally. It reduces sunlight, making it difficult for plants to thrive, and often restricts rooftop and balcony access where small urban gardens might otherwise flourish. This limitation has larger implications: as cities face biodiversity loss and climate change, urban greening efforts are more important than ever. The presence of scaffolding makes it harder for everyday New Yorkers to contribute to these efforts, stalling small-scale ecological action that could otherwise be impactful.

(Poole, 2022)

But what if we could rethink scaffolding not just as a barrier but as an opportunity? I think citizen science provides a way for New Yorkers to document and counteract the negative environmental effects of long-term scaffolding while actively contributing to urban biodiversity research. One of the key roles of citizen science is observation, crowdsourcing data that scientists alone would never be able to gather at such a large scale. In the case of scaffolding, residents could document how these structures affect light levels, temperature, air quality, and plant health. Mobile apps like iNaturalist or NYC-specific platforms could be used to track changes in pollinator activity in areas covered by scaffolding versus open-air spaces. Participants could log which plants survive and which struggle under scaffolded conditions, creating valuable data sets for urban ecologists and city planners alike.

Furthermore, urban gardening organizations and citizen scientists could advocate for alternative designs that incorporate green elements into scaffolding itself. Imagine temporary pollinator-friendly planters installed on scaffolding or city-backed green roofs on construction sheds, solutions that could mitigate some of the ecological downsides. By engaging in citizen science, residents could provide real evidence that green-integrated scaffolding is not just a nice idea but a practical and beneficial one.

Im curious to know, have you noticed how scaffolding impacts greenery in your neighbourhood? What creative solutions do you think could help integrate nature into the built environment?

(McGeehan, 2024)

References:

Wals, A. E. J., Brody, M., Dillon, J., & Stevenson, R. B. (2014). Convergence Between Science and Environmental Education. Science, 344(6184), 583–584. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1250515

McGeehan, P. (2024, April 24). New York City’s Everlasting Scaffolding. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2024/04/24/nyregion/nyc-scaffolding.html

Poole, R. (2022, February 8). Why is There So Much Scaffolding in NYC? - CitySignal. CitySignal. https://www.citysignal.com/scaffolding-nyc/

Haltom, J. (2023). A story of how communities have been shaped by residents learning to garden [University of Guelph]. https://hdl.handle.net/10214/27610

Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial 4.0 International

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hi Natalie,

I really enjoyed reading your blog!

Your post highlights a crucial aspect of art’s role in interpretation; not only does it help us see the world differently, but it also drives action and awareness. I really appreciate your point about art being both a political statement and a source of beauty. Banksy is a great example of an artist using his platform to challenge perspectives and spark conversations. His work proves that art doesn’t just document reality; it can shift it.

Building on this idea, nature interpretation through art isn’t just about capturing beauty—it’s about deepening our understanding of the world around us. Many environmental artists use their work to highlight ecological issues, much like Banksy does. For example, artists like Andy Goldsworthy create ephemeral sculptures using exclusively natural materials, reminding us of nature’s fragility and transience. All of his works are created to be temporary, gradually fading as nature takes its course—ice melts, wind blows, and rain falls—shaping how audiences experience Goldsworthy’s art throughout its brief existence. These artistic interpretations help audiences see beyond what’s in front of them, encouraging a sense of responsibility and connection to the environment.

I also love how you framed “the gift of beauty” as an invitation to pause and reflect. That idea is especially powerful in environmental interpretation, where art can bridge the gap between scientific facts and emotional engagement. Regardless of the medium, art transforms information into an experience, one that can inspire both appreciation and action.

This is one of my favourite sculptures by Andy Goldsworthy: ice between two trunks of an ash tree (AD, 2009)

Nature and Art: Inviting Interpretation

Art invites interpretation, being not only something to be observed, but something to be felt, translated, and shared. Nature speaks in colours, textures, and movement, and I think of nature as a piece of art in itself; something beautiful that evokes emotion, tells a story, and whose beauty is in the eye of the beholder. In the same way that interpreters balance education and recreation to make experiences meaningful, art can capture not just what you see, but what you feel when you engage with nature (Beck et al., 2018).

As an artist myself, I find it very powerful how art can convey a message, and I think artists should take advantage of this influence whenever possible. My opinion may be biased, but I think art in all its forms is one of the most powerful tools to help with interpretation. For example, my parents both lived in Muskoka before I was born, and the town they lived in was surrounded by murals and historical tributes to the Group of Seven. My parents filled our house with these paintings over the years, surrounding me with their rich depictions of Canada’s landscapes. I grew up immersed in this art, becoming inspired not only by the paintings themselves, but by the nature they portrayed and the powerful beauty of the wilderness.

One of my favorite Group of Seven paintings (Thomson, 1912)

Art is a powerful tool for interpretation, but also for invoking action. Back in high school art class, I did a project where the theme was something along the lines of global issues that you feel passionately about. I think this provides a perfect example for this blog post, because it helps display how art can be used as a political statement to inspire change, as well as something to find beauty within.

Plastic Fish, 2019: A painting representing the issue of marine plastic pollution

A similar example of this is the work of Banksy, an English graffiti artist who I admire for his ability to make bold statements about social and political issues. Using his fame and influence to draw attention to deeper subjects, such as environmental issues and humanitarian rights, Banksy reminds us that art can serve as a powerful tool for activism and change.

Graffiti art by Banksy representing urbanization and loss of natural environments (Banksy, 2010)

All this to say, art is inherently connected to broader themes, such as environmental issues and nature, and I believe its significance is extremely important in a changing world with increasing opportunities for our voices to be heard. The “gift of beauty” lies in art’s ability to make us feel, pause, and reflect. Beauty is not just aesthetic; it’s an invitation to connect with something greater than ourselves. Ultimately, interpretation is about connection. Whether through words, performance, or visual arts, it allows us to see ourselves within nature and history. Art museums, much like blogs, thrive on interpretation—offering space for dialogue, reflection, and personal meaning (Beck et al., 2018). Who am I to interpret nature through art? I am someone who listens, observes, and translates—and in doing so, I invite others to see nature not just as it is, but as it feels.

References

Banksy. (2010). I Remember When All This Was Trees. Aerosol on cinder-block wall. Detroit, Michigan. https://beltmag.com/the-fight-over-graffiti-banksy-in-detroit/

Beck, L., Cable, T.T., Knudson, D.M. (2018). Interpreting Cultural and Natural Heritage: For a Better World. Sagamore Publishing LLC. https://sagamore.vitalsource.com/books/9781571678669

Thomson, T. (1912). Canoe [Painting]. Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, Canada. https://www.ago.ca

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Unit 4: Interpreting Nature Through Art—A Gift of Beauty

The question “Who am I to interpret nature through art?” arises for artists and interpreters who strive to capture the essence of nature in creative ways. But perhaps the real question is—why wouldn’t we? Art and interpretation are deeply human acts, woven into our existence since the first cave paintings depicted animals and landscapes. As an interpreter of nature, I do not claim ownership over its beauty but rather the responsibility to share it in ways that inspire, educate, and connect.

The arts have long played a crucial role in shaping how people perceive and protect the environment. As noted in chapter 10 of the textbook, 19th-century artists created paintings that moved Congress to preserve wilderness landscapes for future generations. Their works did more than depict scenic views—they evoked emotions, told stories, and revealed truths about the world that facts alone could not. Today, interpreters continue this legacy, using various artistic forms to foster appreciation for nature. Whether through photography, poetry, music, or theatre, the goal remains the same: to create a meaningful experience that deepens people’s connection to the world around them.

To interpret “the gift of beauty” is to acknowledge that nature’s beauty is more than just aesthetics—it carries meaning, history, and a sense of belonging. Beauty in nature can be found in the resilience of an old-growth tree, the symmetry of a spider’s web, or the shifting colours of a sky at dusk. These moments are gifts not because they are rare but because they have the power to move us and remind us that we are part of something greater. As Jay Griffiths (2013) notes, “Art elicits sympathy, conjures empathy, and these emotions are requisites for a kind, kinned sense of society.” Art, like nature, has a great impact on us all, shaping our thoughts and emotions in ways we may not even realize.

Interpreting the beauty of nature isn’t about simply copying what we see; it’s about finding ways to help others connect with it. A painting of a forest might highlight its vastness, while a poem could describe its stillness and hidden life. Every artistic medium provides a different perspective, helping people engage with nature on a deeper level. In interpretation, professionals use both facts and emotions to help audiences appreciate the value of the natural world. Art plays a key role in this process, transforming complex information into something relatable and memorable.

So, how do I interpret “the gift of beauty”? Primarily through photography and storytelling, with the occasional painting. I don’t paint as often as I’d like—my skills aren’t the strongest—but photography has always excited me. When I’m surrounded by nature’s beauty, photography allows me to capture a moment in time and share that experience with others. It becomes a way to interpret and preserve that beauty, helping others see and appreciate it as I do. Observation and storytelling are powerful tools for forming meaningful connections with the environment. Like the artists and interpreters before me, I strive to present nature in a way that resonates with others, inspiring appreciation and a sense of responsibility.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hi Zoe, thank you for this meaningful post!

To answer your question, the way I interpreted risk vs. reward after reading about The Timiskaming tragedy was that there is an incredibly delicate balance between the two concepts, especially when attempting to “shape character” through challenging experiences. Risk, when appropriately assessed, can lead to personal growth, resilience, and meaningful accomplishments. However, when the risks are disproportionate to the individuals’ preparedness or abilities, the consequences can be catastrophic. In this case, the school's goal of fostering strength and resilience in young boys was overshadowed by a failure to adequately consider the risks involved in their expedition.

Privilege plays a significant role in the equation of risk and reward. Privileged individuals often have access to resources, training, and safety measures that mitigate the risks they face. For example, someone with access to proper gear, experienced guidance, and rescue infrastructure is better equipped to take on challenges safely and confidently. Additionally, privilege provides the safety net of recovery; those with financial or social support systems can rebound more easily from setbacks, whether physical, emotional, or financial.

In contrast, underprivileged individuals face heightened risks due to limited access to these resources. They may not feel safe enough to take risks or may face outsized consequences if things go wrong. This disparity can deter them from engaging in experiences like outdoor recreation, which are often perceived as inherently risky.

As a nature interpreter, understanding these dynamics is critical. Activities must be thoughtfully designed with the audience’s abilities, resources, and backgrounds in mind. The goal is to offer rewarding experiences that challenge individuals while minimizing unnecessary risks, ensuring inclusivity and safety for all.

Understanding Privilege in Nature Interpretation and Education

Defining Privilege

Privilege is the ability of individuals to participate in activities or society in ways that others cannot, due to unearned factors and resources. This creates challenges for people with less privilege in terms of access or ability to achieve. The social inequalities video on Courselink illustrates that everyone has a different background and does not view life from the same perspective or start at the same point. These ideas are crucial for teachers, learners, and people in general to treat others with compassion and empathy.

Privilege and Nature Interpretation

Privilege plays a significant role in nature interpretation and learning in general. Teachers must recognize that their audience may not share the same privileges or even have similar experiences. Everyone comes from different backgrounds and phases of life, but this does not make anyone less deserving of learning about nature. The textbook highlights various groups that may require different formats or accommodations when engaging with nature.

Economic Barriers: Some individuals cannot attend parks or go camping due to lack of transportation, equipment, or the inability to afford trail costs or other fees (Beck et., al 2018). In the future, transportation could be provided, or nature interpretation could be offered in different formats.

Language Barriers: Language differences can deter participation. Trail guides could use multiple languages or include a translator to enhance accessibility.

Physical Barriers: Seniors or individuals with physical disabilities may not be able to hike or engage actively in nature (Beck et al., 2018). To include them, trails could be paved, or nature interpretation could be brought to them through outdoor information sessions. Additionally, for those who are blind or hard of hearing/deaf, descriptive language, sign language, or clear speech without blocking the mouth can be used.

Intellectual Barriers: Audiences could include children, people without access to formal education, or individuals with intellectual disabilities (Beck et al., 2018). Presenting information in a digestible way for all is important.

Acknowledging these differences and accommodating everyone ensures that nature can be enjoyed by all.

Text:

Knudson, L.B.T.T.C.D. M. (2018). Interpreting Cultural and Natural Heritage: For a Better World. Sagamore Publishing LLC. https://sagamore.vitalsource.com/books/9781571678669

Unpacking the Invisible "Backpack"

Unpacking your invisible backpack involves recognizing your privilege and learning about yourself. Teachers must understand what is in their backpack, such as their ability to speak multiple languages or their higher education. Teachers must also understand what’s in the invisible backpacks of their students. This understanding allows educators to create inclusive learning environments tailored to everyone.

For example, you wouldn't teach quantum physics to a kindergarten class simply because you learned it in university.

Risk and Privilege

Privilege generally reduces risk by providing individuals with opportunities and resources that promote success. Privileged individuals have access to resources, support systems, and opportunities for recovery, which help keep them safe. On the other hand, underprivileged individuals may struggle to feel safe in different environments, which can deter them from taking risks. As a nature interpreter, it is important to recognize the specific risks of activities for your audience. The Timiskaming tragedy is a example of this; the teachers did not account for their students' ability to paddle in harsh winds. The school's aim was to build them into strong men, but by overestimating their abilities, the situation ended in tragedy.

How did you interpret the risk vs reward concept after reading about this tragedy? How do you think privledge relates to risk?

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Unit 3: The Role of Privilege in Nature Interpretation