Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Beyond Latkes: Sephardic Hanukkah Recipes and Traditions 🕎

Hanukkah is here and if you are already tired from Latkes dipped in sour cream, here are some traditional alternatives from the Sephardic kitchen.

For a healthier version of Latkes, try Keftes de Prasa- leek patties- popular among Sephardim in the Balkan communities, such as Bulgaria and Turkey. Here the dominant flavor is leek, which is paired with herbs and sometime feta cheese. The use of leek is ubiquitous in the Sephardic repertoire from ancient times. In fact, according to Jewish folklore, being caught cooking leek or smelling of it during the Spanish Inquisition, immediately revealed one’s Jewish identity and led to a sentence of death by torture. Despite this dark chapter, Sephardim remained loyal to their favorite allium for its tender flavor, abundance and low cost. Leeks are the main ingredient in many Sephardic holiday dishes, and here is the Hanukkah one.

Leek Fritters (adapted from Yotam Ottolenghi’s Plenty)

For the sauce (optional but recommended)

-½ cup greek yogurt (I increased to almost 1 cup)

-½ cup sour cream (I reduced to 2 tbsp)

-2 garlic cloves

-2 tbsp lemon (I used 3 tbsp)

-3 tbsp olive oil

-½ cup parsley leaves

-2 cups cilantro leaves

-Blend all the ingredients together in the food processor until they turn green.

For the fritters

-3 leeks cleaned; white and light green parts sliced into 1 inch slices

-5 shallots finely chopped

-⅔ cup olive oil (you may use less depending on need)

-1 fresh red chili pepper, seeded and finely chopped

-½ cup parsley - leaves and thin stalks finely chopped

-¾ tsp ground coriander

-1 tsp ground cumin

-¼ tsp ground turmeric

-¼ tsp ground cinnamon

-1 tsp sugar

-½ tsp salt

-1 egg white

-¾ cup +1 tbsp self-rising flour

- 1 tbsp baking powder

-1 egg

-⅔ cup milk

-4 tbsp melted butter

-Sauté the leeks and the shallots for 15 minutes or until soft on medium heat.

-Transfer into a large bowl and add the pepper, all the spices, sugar and salt. Mix well and allow to cool.

-Whisk the egg white until foamy and add into the veggie mixture.

-In another bowl mix together the flour, baking powder (I recommend sifting dry ingredients to avoid bulks), whole egg, milk and butter to form a batter. Gently pour the batter into the veggie - egg white mixture.

-Put 2 tbsp of oil in a frying pan over medium heat. Spoon half of the mixture into the pan and form 4 large patties. Fry each side for 2-3 minutes or until golden and crisp. Transfer to a platter with paper towels to absorb the oil. Repeat the process to create 8 patties total.

-Serve warm with a spoonful of the green yogurt sauce on top.

On the sweeter side of things, the Israeli national obsession with Sufganiyot (traditionally jelly and nowadays extremely sinful) is definitely rooted in the diaspora. Almost each Sephardic and Mizrachi community makes its own variation of a sugary fritter using the spices common in their country of origin. In India, for example, Jews celebrate Hanukkah with Gulab Jamun- also a popular street food- that is yogurt based and often flavored with cardamom and rose water.

In Greece, Turkey and the Balkans, Jews made Bimuelos often scented with orange blossom, dipped in honey syrup and fried in olive oil. The Iraqi-Syrian’s Zengoula is closer in texture and shape to an American funnel cake.

Last but certainly not least- is the Sfenj- the ultimate North African competitor to the Ashkenazi Sufganiyot. Similar to its French cousin the beignet, Sfenj is simply pastry dough randomly shaped and coated with powdered sugar. It’s extra delicious when eaten fresh off the frying pan.

Ditch the Deep Fryer for Ricotta Pancakes

If frying is not your thing, rest assured that Hanukkah is also celebrated with dairy. Apparently, the miracle of the everlasting oil in the temple and the bravery of the Maccabees is not the only Hanukkah story. In fact, many Sephardic communities honor the heroic act of Judith - Yehudit. According to the Book of Yehudit and Talmudic tales, Judith lured into her home the Syrian Greek General Holofernes, who was attempting to besiege the city of Bethulia. She offered him salty cheese and wine. Once sedated, she killed him and displayed his corpse at the city gates. Seeing what had been done to their commander- terrified the soldiers, and they fled immediately. The liberation of Bethulia raised morale among the tired Maccabee fighters, and helped bring victory one step closer.

'Judith and Holofernes,' 1605, by Jan de Bray.

The crucial role of cheese in the story of Judith gave reason for certain cultures to celebrate Hanukkah with a variety of dairy dishes. A particularly decadent one is the Ataiyef- the Syrian answer to mundane breakfast pancakes. These are stuffed with ricotta cheese, dipped in rose water syrup, sprinkled with pistachio pieces and deep fried, in honor of Hanukkah of course.

A similar and more attainable recipe is the Roman-Jewish Cassola. This simple gluten-free sweet ricotta pancake is perfect for a weekend breakfast on Hanukkah and throughout the year.

Cassola (adapted from Claudia’s Roden Book of Jewish Food)

-1 lb (500 g) ricotta

-1 cup sugar (recipe calls for 200 gram I reduced to 170, and it was still a little too sweet)

-5 eggs

-2 tbsp oil (I subbed for 1 tbsp butter)

-Grated rind of 1 lemon (optional but adds significantly)

-Blend the ricotta and sugar with the eggs in a food processor.

-Heat oil/ butter in a large ovenproof pan.

-Pour mixture into the pan and cook on medium-low flame until the bottom has set firmly.

-Put under the broiler and let it brown for a couple of minutes.

I served it with cherries and berries and a spoonful of homemade granola. No syrup needed!

A Women’s Fest

The story of Judith inspired several Jewish communities to add other customs in addition to the dairy feast. In North Africa, the sixth (and sometimes seventh) night of Hanukkah was known as Chag Ha’Banot - (Eid Al Bana', in Judeo-Arabic), or The Festival of Daughters. During this night, women went to synagogue to pray for the health of elderly women in their community, and to ask for a good match for their single daughters. They lit the Menorah recalling remarkable Jewish heroines, such as Judith and many others. The praying sometimes turned into a lively party featuring singing, dancing and drinking wine.

The feast usually included dairy foods, followed by several desserts, such as sweet couscous with chopped nuts and dried fruit.

This ritual is representative of the endless number of mini traditions existing in the Sephardic-Mizrachi world around Hanukkah. To that point, I am sharing one last non-food tradition- the extra candle. Ladino speaking communities and in Aleppo, Syria, had the custom to light an extra candle each night of the holiday in honor of their ancestors, who were exiled during the Spanish expulsion of 1492. A popular song that accompanied the candle lighting was Ocho Kandelikas (8 little lights in Ladino). Enjoy listening!

youtube

#sephardic

#Hanukkah

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Cosmopolitan Ghetto - The Story of the Jewish Community in Venice

The idea of a long existing Jewish community in Italy may be surprising to some as the bulk of European Jewry concentrated in the central and eastern parts of the continent. Yet, the Jewish presence in Italy is one of the oldest in Western Europe, and it prevailed for centuries with no interruption until the deportations of World War II. This community of mostly Sephardic Jews stretched all the way from Sicily in the south up to the Alpine regions in the north. Evidence of their rich heritage can be found on signage in the cities, such as Via della Sinagoga, Piazza Giudea and Giudecca.

Although Jews gradually integrated into the broader Italian society, spoke Italian and added pasta dishes and ricotta cakes into their culinary repertoire (more on that later), it would be inaccurate to refer to the Italian community as a homogeneous collective. Given Italy's regional diversity, the peninsula’s map is dotted with numerous small Jewish communities, each of them with its unique history and cooking tradition. Venice is perhaps the most fascinating of all.

The First Ghetto in the World

In the early 16th century an influx of Jews arrived in Venice. The majority of the newcomers were refugees of the Iberian peninsula post Spanish inquisition. Their arrival coincided with an internal migration of Jews from the south (mainly Naples, Sicily and Sardinia) and a flow of escapees from German lands suffering from persecution. This massive immigration and the sanitary crisis it created was the reason behind the segregation of Jews in Venice. In 1516, the Doge of the city issued a decree restricting Jews to reside in a gated quarter that was locked at night. The quarter was called Ghetto after the Jewish pronunciation of the Venetian word for “Foundry” because it was situated near an old foundry that made cannons. The ghetto “invention” was soon replicated in other cities in Italy, and eventually became the generic term, known today for low-income segregated communities.

(above- views from the Ghetto)

In addition to the physical restrictions, the Jews of Venice were also professionally confined to only work as doctors, peddlers, merchants and money lenders. Money lenders, in particular, suffered from a bad reputation as greedy and ruthless. Even Shakespeare in England was aware of that when he portrayed the character of Shylock in the Merchant of Venice. To be recognized, the lenders were forced to wear a yellow star on their coats, and later a red hat, and their appearance fueled the antisemitic narrative of the Jewish villain crushing the innocent Christian man.

However, despite these squalid conditions, the Jewish community of Venice prospered. In fact, Historians suggest that since the ghetto was isolated but not hermetically sealed, it provided the Jewish community the autonomy to develop spiritually and intellectually while simultaneously participating in Venice’s rising commerce.

Inside the ghetto gates, the community life centered around Shabbat and Jewish holidays celebrations. In the Scholes (the Venetian term for synagogue), Rabbinic scholars wrote prolifically about religious and social matters. Several of them traveled outside of Venice to Jewish centers in Europe and near east to spread their wisdom on Talmud and Kabbalah. One of the most well-known figures was Rabbi Simon Luzzato, who served as Venice’s rabbi for 50 years during the 17th century. In his pastime, Luzzato wrote extensively on the relationships between Jews and non-Jews. Another important persona of that time was Rabbi Leon de Modena, known as a rabbinical commentator as well as a music composer. Modena was also a compulsive gambler, and some of his writings addressed his addiction. The poet Sara Coppio Sullam was another intriguing figure. Sullam overcame the gender and racial barriers of her time, and ran a salon that drew educated men from within the ghetto and outside it.

The intense scholastic and artistic blossom in the 17th century was boosted by the printing companies established in the ghetto. These publishers printed hundreds of Jewish and non-Jewish content books and made Venice an intellectual capital in Europe at the time. It became a meeting point for traveling Jewish scholars from across the diaspora, who came from afar to exchange ideas with their valued Venetian counterparts.

Outside the ghetto, Jews took an active part in the city’s maritime commerce. The large scale international merchants - among them a few shipowners- were mostly of Portuguese and Levantine descent. They traded oriental goods, including art, wool, silk, sugar, spices, grain, dried fruit and nuts. Also, Jews were to some degree responsible for the spreading of coffee in the continent. Some historians insist that Venetian Jews were pivotal in the coffee import business and that they consumed it as a stimulant for all-night Torah study.

The accumulating wealth of certain Jews created an interior hierarchy within the ghetto. At the top of the social order were the Ponentini - Sephardic Jews - from the Iberian peninsula and Levantini who came from Turkey, Egypt and Syria. In the middle were the Tedechi - German Jews who migrated to the city early on in the 13th century; and at the bottom were the Italians, who mostly came from southern Italy and Sicily. Each one of these communities had their own communal facilities. Among the four synagogues is the extravagant Scola Levantina, inspired by the highly ornamented baroque style of the time. This structure also attracted the non-Jewish residents of Venice.

(Above- the interior of the Scola Levantina)

Christians - poor and wealthy- came inside the ghetto early morning when the gates were opened. They came generally for business purposes but also to experience the holiday celebrations and street fairs, in particular the bright colored Purim carnival. The Jewish elites in the ghetto with their luxurious garments were also quite the sight. Nighttime funerals, in which a beautiful succession of gondolas were lit up by lanterns, were another well known spectacle. These Jewish- Christian interactions evolved into a symbiotic relationship that manifested itself in the intellectual realm, the arts and of course cuisine. And although each side had its share of reservations about the other, there is no doubt about the significance of this exchange of ideas especially during the golden era of the late 16th to mid 17th centuries.

By the end of the 17th century, when the political and economic power of Venice declined, many Jews, particularly those with means, opted to immigrate either to the Americas or eastwards to the territories of the Ottoman empire in search for new opportunities. Despite the diminishing numbers, the ghetto continued to exist another hundred years until Napoleon’s armies occupied Italy in 1796 and broke its gates in accordance with the principle of emancipation. As equal citizens, the Jews in the city were active in the political realm. Luigi Luzzati, for instance, who led the struggle to better the life of the gondoliers, was elected Italy’s first Jewish prime minister in 1910.

Venetian Jews had a fairly tranquil existence until the promulgation of Mussolini’s racial laws in 1938. When the Germans occupied the city in 1943, 1,200 Jews were living in the city, and 200 of them- including the chief rabbi at the time Adolpho Ottolenghi- were murdered in the death camps.

(above - Ottolenghi’s memorial in the ghetto)

Nowadays, Venice is home to a small Jewish community of 500 people mostly run by the Orthodox chabad center. Only 30 Jews were recently recorded living in the vicinity of the former ghetto. However, the ghetto and its institutions (the 4 synagogues, museum and cemetery) are considered worthwhile tourist attractions.

Where Pasta Meets Chicken Soup- Jewish Venetian Cooking

The cultural interchange between Jews and non-Jews and among the many layers within the Jewish community created a unique and rich Jewish Venetian cuisine.

Inside the ghetto the Levantini introduced the concept of rice pilaf, and particularly rice with raisins. The Iberian Ponentini brought in salt-cod dishes, vegetable frittatas, almondy sweets, orange cakes, flan and chocolate desserts. Both of these groups used a variety of spices (such as saffron), which made their cooking fragrant and excotic especially at a time where condiments were rare and expensive. Sicilian Jews contributed lemons (and lemonade) and pine nuts into the mix. The combo of raisins and pine-nuts became the trademark of the Venetian Jewish cooking, and was served with rice or with fish dishes, such as marinated sardines. The German Tedeschi added heavier meaty ingredients, such as duck sausage and meatloaf with hard boiled egg in the middle. The Ashkenazi knaidlach was refined and became Cugoli- a pasta dough dumpling served with chicken soup. Another example of a multicultural dish created in the ghetto is the Burriche- a savory pastry in between a Portuguese empanada and a Turkish bourekas with Italian fillings, like fish with hard boiled egg or anchovies and capers with fried eggplant.

Because of their foreign origin and their extensive travel as merchants, Jews had an important role in putting new dishes on the Italian table. In fact, some Italian staples, such as almond based sweets or puffed pastry are essentially “Alla Guidia” meaning of Jewish origin. Chrisitians were particularly inspired by the variety of vegetables- including zucchini, cabbage, eggplant, peas, potatoes and spinach- in the “Jewish diet”. Guiseppe Maffioli, the author of La Cucina Veneziana, remarks that the Jews were admired for the sense of imagination in the kitchen, as they mixed together ingredients considered exotic or even forbidden (eggplant, for instance, was initially labeled as the food of the devil) into everyday dishes, such as risotto and pasta.

(above - a Jewish bakery in the ghetto)

On the other hand, Jews were clearly influenced by their Christian neighbors, and their creativity as cooks helped them overcome the limitations of kosher dietary laws. The classic melon and prosciutto antipasto was served with fried eggplant instead of meat in Jewish households. Similarly, pork was substituted with duck or goose because of their fattiness. The hearty and spicy fish stew- is another example of a Jewish speciality emulating a local dish that originally used shellfish. Pasta was eagerly adopted by the Jewish community starting from the 16th century, and many variations of it were created for Jewish festivities. For instance, on wintry Shabbats thin pasta noodles were added to the traditional chicken soup. On Shavuot, it was traditional to make pasta with ricotta cheese and spinach and macaroni with cream and butter. In Purim, Jews prepared sweet pasta with sugar and cinnamon. Risottos were also very popular among Venetian Jews, and were served either with spices (such as saffron) or seasonal vegetables. Unlike typical risotto, Jews often slow cooked the grain instead of stirring constantly. The result is in between a rice porridge and a risotto, a perfect food on a cold Shabbat night.

Riso coi Carciofi- artichoke risotto- embodies the qualities of the Jewish Venetian cooking described above. This particular version was created by the inhabitants of the ghetto who migrated from Sicily, where artichokes were growing wild. This dish is very easy to make especially if using frozen artichoke hearts. Unlike a typical risotto made with beef broth and butter, this variation calls for white wine and vegetable oil, which makes it vegetarian friendly.

Artichoke Risotto - adapted from Claudia Roden’s book, The Book of Jewish Food

2 ¼ cups water

2 ¼ cups dry white wine

8 tbsp sunflower or vegetable oil

1 ¼ cups italian risotto rice (Arborio)

Salt and pepper

14 oz (400 gram) artichoke hearts defrosted

1.Bring water and wine to boil in a medium size small pan.

2.Simultaneously, in a frying pan, heat 4 tbsp of oil, add the rice and stir until it is coated and translucent.

3.Pour the rice into the wine and water, add salt (½ teaspoon) and peeper, cover and simmer for 20 minutes or until the rice is tender but firm, and there is a little liquid.

4. While the rice is cooking, heat 4 tbsp of oil in the frying pan and add the artichoke hearts and some salt. Keep stirring until the hearts are slightly brown.

5.Once the risotto is cooked add the artichoke with a slotted spoon at the top.

Enjoy as is or add freshly grated parmesan for additional flavor (highly recommended).

The Only Daughter- Jewish Venice in the Eyes of the Literature

The literature piece chosen for this post takes the reader far away from the lively renaissance days into the gloomy existence of the Jewish community in Venice today. The book The Only Daughter by A.B. Yehoshua is a portrait of a shrinking, dying, highly assimilated community with no prospect of renewal.

Rachele Luzzato, the heroine of the story, is the only child of a well-to do Jewish lawyer and a converted Italian mother. Although raised Jewish, Rachele is attached to her catholic maternal grandparents, and drawn to their religious traditions. In fact, one of the threads in the book is Rachele’s disappointment when her father forbids her to participate in the school’s nativity play. Rachele adores her father, and they have a sweet close relationship. Sadly though the father is dying from a brain tumor, and his impending death is clearly a metaphor to the state of the Venetian (and overall Italian) contemporary Jewry. This leitmotif of decline also appears in the side story of the Jewish tutor. As Rachele reaches the Bat Mitzvah age, she and her friend are taking Judaic lessons given by an orthodox rabbi from Israel. The rabbi is single and he arrives in Venice on a mission to find a proper match. Yet, much to his dismay, there is no inventory! Accepting the circumstances, the rabbi loosens up and participates in the carnival party organized by Rachele’s Jewish grandmother. Ironically he disguised himself as a priest. Being so convincing in his catholic appearance, the guests in the party approached him as “father”.

A.B. Yehoshua, one of Israel's top living authors undoubtedly blends in his political agenda in this tender tale about a Jewish adolescent. Yehoshua is a vocal speaker about the diminishing diaspora, and his arguments against assimilation and the urge to strengthen the bond with Israel cause a great controversy in the Jewish world.

(above- A.B. Yehoshua and myself)

In the case of The Only Daughter the choice of Venice for location is not coincidental and speaks of the imminent crisis. The concept of a city with a glorious past physically sinking down alongside a history of heavy plagues (including the black death in the medieval and several cholera outbreaks between 1817-1923) inspired many writers to choose Venice as setting for stories about decay, notably Thomas Mann’s novella Death in Venice (one of my absolute favorites).

Regardless of your views on the matter, reading the Only Daughter is highly recommended. It is beautifully written and masterfully conveys the mysterious charm of Venice.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mediterranean Medley: The Jewish Community of Tunisia

Tunisia is currently making global headlines. A decade ago the Tunisian protest for democracy sparked the “Arab Spring”, which led to vast political shifts in the Middle East. Now, its citizens are fighting to retain their past achievements and curb the ruler's authoritarian pursuits.

The recent events in this small country on the southern shore of the Mediterranean also provide an opportunity to discuss its Jewish community, a community small in numbers yet incredibly diverse in terms of socio-economic status and cultural orientation. This entry is therefore dedicated to exploring the complex history of the community, including the particularly tragic chapter of the Nazi occupation during the Second World War. As always fiction and culinary elements will be weaved into the discussion.

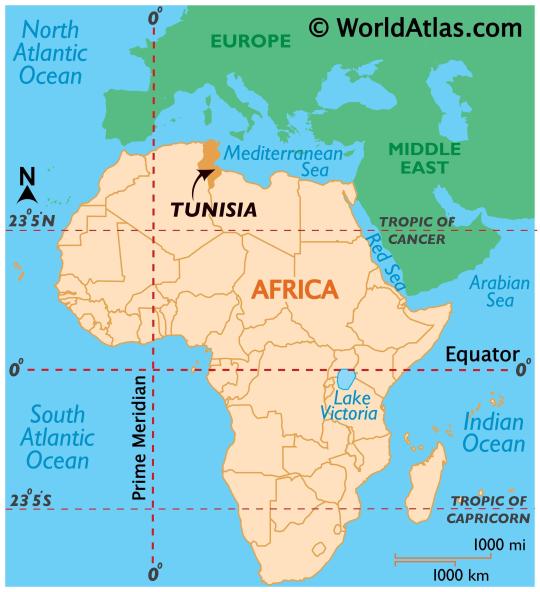

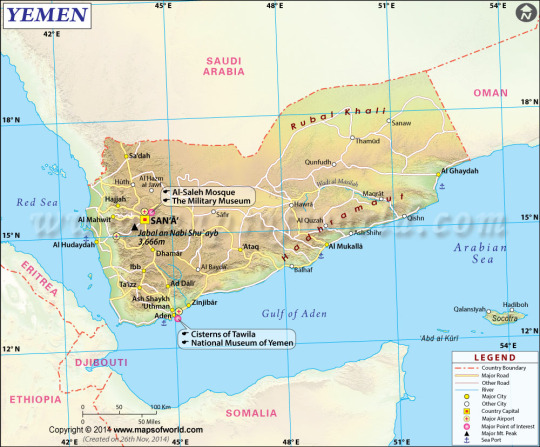

(Tunisia on the map: between Africa and Europe)

Berber, Italian and French Mix

The Jewish community of Tunisia settled mostly in the coastal areas in the cities of Tunis, Sousse, Sfax, Bizerte and Monastir. There were also several rural Berber communities, in which Jews lived a semi-nomadic life.

(The beautiful coast)

The origin of the Jewish community is disputable. Members of the community claim the first settlers migrated from Jerusalem after the destruction of the second temple in 70 CE. Several scholars, however, ascertain that the community originated from the conversion of either Phoenicians or Berber tribes.

Origin aside, archeologists indicate a viable Jewish presence beginning in the fourth century CE. Evidence also shows connection between Tunisian Jews and Jewries in Persia, Israel and Iraq. The Bagdadi community and its Talmudic centers, in particular, was a source of inspiration fueling the local Torah learning, and overall intellectual life.

In the fifteenth century, Andalusian Jews found refuge in Tunisia while escaping the Spanish Inquisition. Their influence is notable in architecture, culture, and clearly cuisine. Another wave of Jewish immigrants arrived to Tunisia from the Italian port city Livorno during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. The Livornese Jews, mostly Portuguse Marrano descendants, built maritime trade between North African hubs to European Mediterranean port cities. In 1741, the Livornese community (also called “Grana”) asked for autonomy on the pretext of having a different liturgy. Followed by this act, two separate communities- native and Livornese- were formed. The two sub-communities had their own rabbis, synagogues, cemeteries and philanthropies. The Livornese section, which actually encompassed all European Jews whether they came from Italy, France, Gibraltar or Malta- prided themselves as superior. They refrained from intermarrige with the native Jews, refused to speak Judeo-Spanish and continued speaking Italian. Some of the Livornese became rich bankers and merchants, but many were weavers, tailors, shoemakers, and even lived in poverty relying on charities.

In the cities, since Medieval times, the indegenous Tunisian Jews, lived in the margins of the Muslim areas and the Souks, in quaters named Haras. The Haras became overpopulated starting in the second half of the nineteenth century with poor sanitary conditions, and no running water nor electricity. The residents of the Hara were mostly craftsmen- tailors, potters, leatherworkers and silversmiths. Those who could afford it, left the Hara to settle in the European quarters built by the French.

(The Hara of Tunis, image #1)

(The Hara of Tunis, image #2)

The French Colonization, starting in the late nineteenth century, created a new elite of Francophones. The upper Jewish class eagerly fostered French as their mother tongue, named their children in French names and sent their children to schools in Paris. The few, who managed to obtain key posts in the new colonial governments, were granted French citizenship, but the majority including some of the wealthiest families remained with the status of subjects.

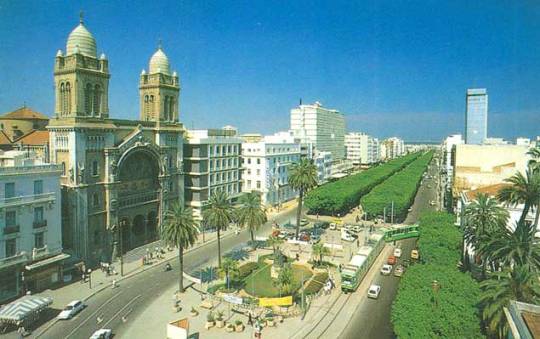

(The French Quarter of Tunis)

Despite the strong French influence, Tunisia continued to be fairly diverse as a port country luring people from different parts of the Mediterranean basin. Thus, the Jewish population (unlike their brothers in neighboring Algeria) lived in a multicultural environment, in which Greeks, Maltese, Italians and of course Arabs co-existed and influenced one another.

A Boy in a Ruthless City: The Nazi Occupation through the Eyes of an Adolecent

The cosmopolitan climate described above was the setting of Albert Memmi’s (1920-2020) semi-autobiographical novel, The Pillar of Salt. In the book, Memmi, a distinguished philosopher known for his work on Colonial Studies, disguised himself as Alexandre Mordekhai Bennillouche, a poor Jewish boy growing up in the Hara of the capital, Tunis.

( Albert Memmi)

Bennillouche (or Memmi) begins his account in describing his happy childhood as an age of innocence and unawareness to his poverty and inferior status as a “native Jew”. Gradually, the protagonist discovers the world around him. He excels at school, but suffers from anti-Jewish violence from Chirsitan and Muslim peers. Given his academic performance, he is given a stipend to study in one of the city’s top schools, where he is introduced to the upper circles of the Jewish community and the general European society. This exposure causes a rift in the relationship with his parents, who resent his education wishing for him to continue the family leather business. Although deeply ashamed of his parents - their meager existence and traditional views- Bennillouche is quickly disillusioned from the enchantment of the elite. Being a critical thinker, he spots its insincerity and snobbery, yet he is forced to hide his contempt as he is dependent on their funds for his schooling.

(The capital- Tunis)

The six month Nazi occupation of Tunisia (November 1942- May 1943) reaffirms Bennillouche’s beliefs about the hypocrisy of the elite. During the short- yet traumatic - German presence, Tunisian Jews were subject to constant harassment from the occupiers and general population, and were under the imminent threat of being deported to the death camps in Europe. Yet, the degree of Jewish misery varied based on socio-economic belonging. When the Germans issued a decree for Jewish forced labor, the wealthy ones of the community paid ransom to exempt themselves and their dear ones. Impoverished men- however- were destined to greater hardship.

(Jews assigned for forced labor)

Benillouche (and Memmi himself) was one of the unfortunate people. Despite being friendly with people in high places, and holding a prestigious teaching position, he was deported to a concentration camp in the Saharan desert. There, he suffered from the brutality of the guards, the senseless work, and above all the merciless sun. However, camp was also a place of revelation. The hardship created a sense of comradery between Benillouche and his fellow inmates, of whom he shared similar upbringing. He was even reunited with some old friends, and enjoyed conversing with them in his childhood dialect of Judeo- Arabic, which he neglected in favor of French. In addition, the camp helped him to rediscover and reconnect to his Jewish roots, as he was asked to lead Shabbat prayers as the camp’s intellectual figure.

By the time the camp was released by the Allies, Bennilouche was a more grounded man. He still continued to march according to his original trajectory in the academic world but with a wiser outlook on life.

Topped with Harissa: A Quick Peek to Jewish-Tunisian Cuisine

Even while estranged from his family traditions, Bennilouche always maintained a fondness for his mom’s traditional Tunisian cooking. In fact, he recounts nostalgically the smells of Shabbat dishes cooking slowly in the tiny kitchen of his childhood home. When he matures, he recognizes the power of food as a source of comfort and festivity in a household that is poor and filthy. One of the dishes he highlights is Bkeila (also pronounced Pkeila) - a hearty spinach and beans stew served vegetarian or with beef. Below is Yotam Ottolenghi’s take on it from his latest cookbook Flavor.

Bkeila, Potato and Butter bean Stew - Adapted from Flavor

(See my notes below to simplify the cooking process)

4 cups (80 gram), roughly chopped cilantro

1 ½ cups (30 gram) parsley

14 cups (600 gram) spinach

½ cup (120 ml) olive oil

1 onion (150 gram), finely chopped

5 garlic cloves, crushed

2 green chiles, finely chopped and seeded

1 tbsp plus 1 tsp ground cumin

1 tbsp ground coriander

¾ tsp ground cinnamon

1 ½ tsp superfine sugar

2 lemons: juice to get 2 tbsp and cut the remainder into wedges

1 qt/ 1L vegetable/ chicken stock

Table salt

1 Ib 2 oz/ 500 gram waxy potatoes, peeled and cut into 1 ¼ inch pieces

1 Ib 9 oz/ 700 gram jar or can of butter beans, drained

1.In batches, put cilantro, parsley and spinach in a food processor until finely chopped. Set aside.

(Massive amounts of greens)

2.Put 5 tbsp of olive oil into a large heavy-bottomed pot on medium heat. Add the onion and fry until soft and golden, mixing occasionally (about 8 minutes). Add garlic, chillies and all the spices and cook for another 6 minutes, stirring often.

3.Increase the heat to high and add the chopped herbs and spinach to the pot along with the remaining 3 tbsp olive oil. Cook for 10 minutes, stirring occasionally until the spinach turns a dark green. The spinach should turn a little fried brown but not burn. Stir in the sugar, lemon juice, stalk and 2 tsp salt. Scrape the bottom of the pot if needed. Bring to a simmer, then decrease heat to medium and add the potatoes. Cook until they are soft for about 20-25 minutes and then add the butter beans and cook 5 minutes longer.*

(Butter beans to break the deep green)

4.Divide into bowls and serve with lemon wedges.**

* As this dish was traditionally slow cooked using a slow cooker pot or a pressure cooker could easily do the trick. If using these- do the following: Skip step 1. Saute the onions, garlic, chilli and species as instructed in step 2. Then add the rinsed spinach and herbs. Mix them well with the onions and spices in the bottom. Once the spinach begins to melt, mash them using a hand blender and then add the ingredients described in step 3 (beside the butter beans). Then let it slowly cook until everything softens. In the end, add the butter beans and press on the “stay warm” button.

(loading the pot with spinach)

** I served it with bulgur to soak up the liquids a bit (rice, farro or any other grain will work as well). I also added hard boiled eggs for additional protein.

(Healthy and heart)

In addition to the Bkeila- The Tunisian Shabbat table will not be complete without the famous couscous. The process of making it from scratch without a food processor was quite laborious, but the result - whether served sweet with nuts and spices, or savory with meat stew or fish - was considered a delicacy.

The proximity to the Mediterranean shore brought fish dishes to the Jewish- Tunisian repertoire. Fish is mostly eaten fried or cooked as fish balls or oven roasted served with red hot sauce. Meat is also often served spicy, and often chunks of hot merguez sausage are added to stews or shakshuka.

Generally speaking, Tunisian Jews are fond of hot flavors, and their cuisine is potentially the spiciest in the diaspora (perhaps only second to the Yemeni). Harissa paste, now increasingly popular around the world - is liberally used to spice up any dish. This fiery red pepper condiment is added - for example- to the famous Tunisian fricassee, one of Israel's most popular street foods. Click here for a recipe for this tuna loaded sandwich, and here to learn more broadly about Tunisian cuisine.

(Tunisian Sandwich with some Harissa)

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Beyond the Purim Story: An Introduction to Persian Jewry

Centered in the ancient capital of the Perisan Empire, the story of Purim offers a glimpse into the life of the Iranian jewry- a long standing community with roots beginning in biblical times to Contemporary Iran. In the Megillah, the orphan Esther, paves her way into the royal court, and later saves her Jewish people from destruction. Although historically questionable, the Purim tale in many ways, is a microcosmos of the history of the Iranian community. A saga that could be sketched as a linear graph with sharp ups and downs, from regality to poverty, from great political power to persecution. And to add to this extraordinary trajectory, It is also one of the few Jewish communities still existing (rather miraculously) in large numbers in a Muslim country, and under radical theocratic regime.

A portrait of Queen Esther

Despite this fascinating history and the important contribution of Iraninan Jews to global commerce (which will be discussed later), the topic received very limited scholarly attention. In fact, less than a handful of books were dedicated to Persian Jewry. I lament this on a personal level as I am Iranian from my paternal side. Therefore, this post is a humble attempt for reparation. It contains a short historical view, and aims to provide a sense of its rich folklore through the lens of fictional literature and culinary.

Major Milestones in the History of Persian Jews

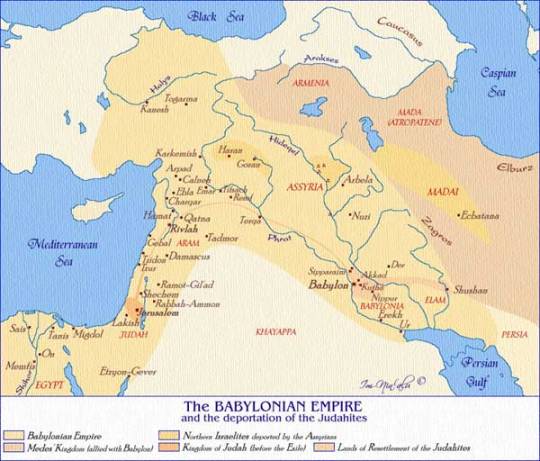

The Persian community is one of the oldest ones in the diaspora as it dates back to the Babylonian exile in the fourth century B.C. For the two centuries to follow, the Perisan community was linked to the Jewish communities in Babylonia and Mesopotamia. The famous Yeshivot (Torah learning academies) in Sura and Pumbedita, in which the Babylonian Talmud was crafted, were a source of guidance for the refugees in Persia. To this day, the Iraqi and the Persian communities bear much resemblance in terms of culture and religious practice. Their cooking (later discussed) is similar as well.

Babylonian Exile map

In ancient and medieval times, the Jews of Persia were well known as savvy and wealthy merchants. Situated in a prime location between China and India and Europe, Persian Jews were pivotal in what was then global commerce. Through the Silk Road and other networks of trades, Persian Jews imported spices and other goods, such as rice and tea to the west.

Silk Road’s Routs

Persian Jews were influential and properous through the first generations following the Arab Muslim conquest of Iran in the third centry A.D. Their status and living conditions deteriorated significantly with the accession of the intolerant Shiite Safavid rule. Under a regime, in which non- Muslims were considered impure heretics, Persian Jews were pushed to the margins of society and poverty. Excluding a short resurgence during the Sunni Mogul takeover of Persia in the sixteenth century, the Persian community lived under hardship and fear. The Shiite Shahs harshly oppressed minorities, denying them any position of power and restricting them to a few professions and areas of living. In several episodes in the course of the seventeenth, eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, Jews were expelled from the cities they lived in and forced to convert to Islam. Subsequently, many Persian Jews fled to Iraq, Syria, Samarkand and Georgia.

The economic and overall living situation improved in the late nineteenth century as Iran increasingly opened to the west. Although still segregated in Jewish quarters, urban Jews pursued western education. Jews, including women, gained proficiency in languages, such as English and French. They also increased their integration into local Iranian society, and named their children in both Hebrew and Parsi names. Jewish women did not veil, but they adopted the black Chador to cover their faces when out of the house. Similar to other Jewish communities at the time, girls were betrothed at age 8 or 9 and married when they were about 16. It was common for women to pilgrim to other parts of the country to visit sites, such as Queen Esther’s burial place, near Isfahan.

Queen Esther’s Tomb

The rise of the Pahlavi dynasty in 1925 marked a turning point. This transformation allowed the Jews once more to be in a position of influence both politically and economically. Many immigrated from the hinterland to Teharn to explore new opportunities, and a few became close to Risa Shah and other men in powerful posts. For the most part, this elite chose to stay in Iran after Israel’s Independence. The lower and middle class Jews opted to immigrate to the new Jewish State in 1948.

The Muslim revolution in 1979 drew a sharp decline in the status and overall safety of Iranian Jews. After decades of prosperity, the Jewish community was once again isolated and in grave danger. The initial period of the new Isalimic republic was particularly traumatic given constant harassment and even execution of several Jewish businessmen for their alleged connection to Israel and the United States. In the following years, the situation seemed to stabilize, and Jews were given a certain degree of religious autonomy. Although most Iranian Jews fled the country in several waves in the aftermath of the revolution, a sizable group remained. Today, their number is estimated at nine thousand. Given the lack of reliable information, their overall condition is unclear. Recent imgirants paint an ambiguous image of harmony with Muslim neighbors, and yet a feeling of imminent threat. Unsurprisingly, Iranian news reports emphasize the community’s well being and alignment with the regime.

Images of contemporary community life

Outside of Iran, Israel and North America are the main hubs of Iranian Jewry and smaller pockets exist in London, Melbourne and Buenos Aires. Two significant communities in the United States are located in Great Neck, New York (also known as Persian Island) and in Los Angeles (it’s estimated that about 25 percent of Beverly Hills population is of an Iranian- Jewish descent). Many of the immigrants in America were able to bring their fortune to the new land and used their capital and expertise to start businesses in the clothing, food and electricity industries.

In Israel, as an attempt to integrate, Iranian Jews adapted to the culture and values of mainstream society while leaving their own heritage behind. This may be a gross generalization, but sociological studies, statistics and experience of living in Israel suggest a trend of assimilation. As a result of their pragmatism, Iranian Jews have made great accomplishments in the sphere of public service. The IDF, in particular, was a stepping stone to obtain power within the military (and later in Israeli politics). Among its current and former ranks, one can find a high number of generals of Iranian descent, including two chiefs of staff.

Real Persian Housewives

An exception to the unspoken policy of concealing Persian legacy is the author Dorit Rabinyan. Born in Israel into a warm tight knit Iranian family, Rabinyan used her gift for writing to bring Persian tradition into the spotlight. Inspired by her grandmothers and aunts’ tales of life in the old country, Rabinyan published her first novel Persian Brides (titled in Hebrew, The Almond Tree Road in Oumrijan) when she was only 21 years old. The book, an immediate bestseller, was widely translated and praised by critics, describing Rabinyan as a meteor and comparing her to Gabriel García Márquez”.

Dorit Rabinyan

In Persian Brides, Rabinyan masterfully crafted a new hybrid of Hebrew- rich and whimsical -Parsi sounding text. Through her vivid language, Rabinyan invites the reader to experience the surreal Persian village of Oumrijan in the dawn of the twentieth century. The plot centers around two maidens, Flora and Nazie Retoryan, and their dramas involving marriages, pregnancies and relationships with their neighbors and the village demons.

Since marriage is a central thread in the book, there are many descriptions of ceremonies and superstitions involving the bride to be. One of them, hilarious and sad at the same time, is the qualification test performed the day before the wedding. This is a test run by the mother of the groom in order to assess if the future daughter in law will qualify as a housewife. So what makes a good Persian housewife? The answer is superior herb chopping skills... perhaps understandable given the amount of vegetables used in Persian cooking (see section below). During the test, the poor girl needs to demonstrate how quickly and meticulously she handles a massive amount of greens needed for Khoresht Sabzi- a traditional stew. The pressure around the “Sabzi test” was so daunting that bleeding injuries, including losing fingers, were common. Here is the excerpt from the book:

“The bride had to prove her skills in cleaning and chopping the Sabzi, the herbs that Janjan sold in the market...the women of the village and relatives circled the bride...On a silver tray, they put bunches of celery, traggon, sage, rosemary, mint, spring onions and parsley. Homma (the bride) was sitting on the ground with her legs crossed as the Sabzi stems hill reached all the way up to her breast… Homma began quickly by separating the leaves and the roots from the celery, the spring onion stems from its onion, the sage from its delicious smelling flower buds, all of these were soaked in a big water bowl. later, the mint, tarragon and parsley leaves were washed as well...Homma reached for the sharp knife. Its blade was shining, and the women were shushing each other. Nazie knew that the tested brides sometimes get injured because of the pressure, and sometimes they even cut off their fingers. When that happens they deposit the cut finger with their mother, and continue to chop while they are heavily bleeding. But if not a single blood drop spilled during the test, and the herbs were finely chopped, the women sang and danced in circles around the bride as she was proven to be a skillful and well trained cook at her parents’ kitchen”.

Khoresht Sabzi Recipe

In honor of poor Persian housewives, I am including here a recipe of Khoresht Sabzi. This is a more user friendly version of this staple dish as it allows using dried herbs (although I highly recommend fresh for flavor), and it calls for a smaller variety of herbs. Note though that other available herbs (for example, dill, traggon, basil) will be a wonderful addition to the herbs listed below. In addition, middle eastern grocers sell pre cut Sabzi mixes (either dried or frozen), which can make the process even easier. Lastly, I listed lamb as one of the ingredients, but variations are welcome. In my family, Khoresht Sabzi was served with chicken, but it is also fabulous as a vegan dish (see modification below) as I prepare it.

Khoresht Sabzi- Adapted from Najmieh Batmanglij’s book Food of Life: Ancient Persian and Modern Iranian Cooking and Ceremonies.

6 tbsp oil, butter or ghee

2 large onions thinly sliced

2 pounds lamb shank (optional)

2 tsp salt

1 tsp ground pepper

1 tsp turmeric

½ cup drained kidney beans - either canned or soaked overnight (increase the amount to 1 cup if omitting meat)

2 whole limu- omani - dried persian limes pierced

4 cups finely chopped fresh parsley or 1 cup dried

1 cup finely chopped fresh chives or scallions or ¼ cup dried chives

1 cup finely chopped fresh cilantro

3 tbsp dried fenugreek leaves or 1 cup chopped fresh fenugreek

¼ cup lime juice

1 tsp ground cardamom

½ tsp of saffron threads dissolved in

2 tbsp of rose water (or hot water)

Let the chopping begin

1. In a large saucepan (preferably a dutch oven), heat 3 tbsp oil over medium heat, and browned the onions and meat (if using). Add salt, pepper and turmeric, and sauté for 1 minute.

2.Pour 4½ cups of water, and add the kidney beans and dried limes. Bring to a boil, cover and simmer for 30 minutes stirring occasionally.

3.Meanwhile, in a wide skillet, heat 3 tbsp oil over medium heat, and sauté the parsley, chives, cilantro and fenugreek for about 20-25 minutes stirring frequently to avoid the burning of the herbs.

shrinking herbs

4. Add the herbs mixture, lime juice, cardamom, and saffron with its water to the large saucepan. Cover and let simmer for 2 -2 ½ hours, stirring occasionally.

Simmering slowly

5. Check if meat and beans are tenders and add salt if needed.

6. Serve warm on a bed of steamed basmati rice.

Gratifying bowl on a cold winer night

Festive, Aromatic and Nutritious: A General Note on Persian (and Jewish) cuisine

Khoresht Sabzi - quintessential among Jews and their Muslim neighbors- can shed light on the Iranian kitchen as a whole and its link to Persian folklore. The Israeli celebrity chef, Yotam Ottolenghi wrote on this topic, in his book Plenty More:

“My Previous life must have been somewhere in old Persia. I am absolutely convinced of this. I am completely infatuated with the richness of Persian cuisine, by its clever use of spices and herbs, by the inguianty of its rice making, by pomegranate, saffron, and pistachios, by yogurt, mint, and dried limes. It seems that my palate is just naturally honed for this set of flavors”.

Ottolenghi’s words well capture the exotic and diverse essense of Persian cuisine. Specifically, the culinary practices of contrasting dominant flavors (obtained by adding sour taste, such as pomegranate or lime juice to savory dishes), and textures (for instance, the combination of dried fruit and herbs) are indeed extraordinary. The slow cooking of a wide array of fruit (such as pears, apricots, dates and cherries), nuts (pistachios, almond and walnut) and spices (saffron, cinnamon and turmeric) also add a layer of complexity and colorfulness.

Typical Persian assortment

The Zoroastrian concept of duality between good and bad, light and darkness -embedded in Iranian culture- was a key factor in the development of Persian cuisine. It inspired the aforementioned balance between sweet and sour, hot and cold, lean and fatty that exists in many dishes. Concerned with health, and mainly digestion, Persian cooking offers a dichotomy between hot foods, which thicken the blood and increase the metabolism, and cold foods that do the opposite. Dates and grapes are, for instance, “hot”, while plum and oranges are “cold”. A diet consisting only of one type of food can essentially imbalance the body and lead to an illness. Accordingly, the high consumption of herbs and green vegetables in almost every meal also stems from the concern regarding nutritional properties adjuncting food and medicine.

Iran’s historic role in importing goods from the far east and its interactions with its neighboring regions also shaped the culinary culture. Particularly, the Mogul - indian conquest and the long Ottoman reign increased the selection of spices, and introduced dishes, such as baklava and yogurt to the Iranian repertoire. These interchanges also spread Iranian staple dishes to other parts of Central Asia and the Middle east. Sephardic communities in these areas, particularly in Iraq and Turkey, adopted the Persian combination of fruit with meat, and rice with legumes.

Rice is perhaps the most iconic Iranian staple. It is made with a sense of perfection aiming to avoid porridge-like texture. Rice is commonly prepared either as Choleh - steamed with saffron scent and a crunchy crust (Tahdig) or as pilaf - mixed with vegetable, fruit and beans. A very colorful pilaf is the Wedding rice served with almonds and dried fruit.

The Art of Tahdig

Hearty stews, known as Khoreshts (such as the aforementioned Khoresht Sabzi) frequently accompany the rice. Khoreshts are vegetable and herb based but utilize local ingredients unique to specific regions of the country (caviar in the Caspian sea area, for example). Another important dish is Kuku- a savory bake that can be compared to crustless quiche (or an Israeli Pashtida). Popular Kuku are made out of herbs, eggplant (also known as Iraninan potato) and my favorite cauliflower. At the end of the meal, Iranians enjoy a cup of tea served with a sugar cube and a nut based treat, such as nougat or walnut cookies.

Kuku: Colorful and heathy

Persian-Jewish cuisine is basically identical to the majority cuisine with one main distinction. Due to Kosher dietary laws that separate meat and dairy, Jews refrained from using Ghee (clarified butter) and yogurt in meat stews. Iranian Jews contributed a very popular dish to the Iranian collection - Gondy chickpeas dumplings that are traditionally cooked in chicken broth.

Gondy: The Persian answer to Matzah Balls

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Sephardic Communities in Jerusalem - The Invisible Walls of the City

Diaspora is defined as the dispersion of the Jews beyond Israel or as Jews living outside Israel. Accordingly, this blog has thus far explored the life of Sephardic communities in various countries in the Mediterranean Basin and in the Middle East. This post, however, is a special one as it is dedicated to a group of Sephardic communities that have been residing in Israel for over 500 years. These Sephardic communities left their diasporic homes towards the ancient homeland starting in the 16th century, but still to this day operate within their old and somewhat isolated diasporic mode of speaking their own dialect, resolving conflicts in community structures, and marrying among themselves. As the holy capital, the city of Jerusalem became a hub for those types of Sephardic communities, and for that reason, it is the focus of this blog post.

A Peculiar City

As a sacred place for the three monotheistic religions, Jerusalem attracts people from a wide array of origins to settle in it. A short walk in the city streets reveals how incredibly diverse and complex it is. Every neighborhood encompasses a different world of language, culture, and worship. Sometimes within a distance of a few houses, the scenery changes dramatically: Arabic replaces Hebrew or Yiddish and affluent residences transform into low-income housing. It is not a rare sight, for instance, to witness an old Palestinian shepherd letting his sheep graze in the front lawn of an urban neighborhood. Being so hard to define or explain, no wonder that the late Amos Oz, one of Israel’s most renowned authors, called the city “one of the most peculiar places on earth.”

Unfortunately, as well reflected in global news, the relationships between the various ethnic and religious groups in the city are far from being harmonious. Clashes minor or major occur daily, fueling the already heated climate. The late Israeli poet Yehuda Amichai, a longtime resident of Jerusalem, repeatedly lamented about the friction in his poems. Below is a passage from his poem “Jerusalem,” which beautifully captures the city’s animosity:

On a roof in the Old City

Laundry hanging in the late afternoon sunlight:

The white sheet of a woman who is my enemy,

The towel of a man who is my enemy,

To wipe off the sweat of his brow.

(Above- the different communities in the Old City)

Even within the Jewish context, there are invisible walls dividing the numerous religious sects and various ethnic groups, which exist beyond the obvious separation from the ultra-orthodox sector. The Sephardic community, as previously mentioned, is an umbrella name for multiple groups that are separated from each other linguistically and culturally, as they originated from various parts of the world, such as Uzbekistan, Bulgaria, Yemen, Iran, and more. Although these communities have maintained friendly relationships on the surface, there is a strong sense of segregation between the communities, each keeping its gates closed for outsiders. Even the formation of the State of Israel that unified everyone under the idea of one nation could not dissolve these firm barriers.

This post will look into these communities and specifically showcase two distinct groups: the Ladino speaking community and the Bucharian (Uzbek) neighborhood, through art and culinary.

Ladino Speaking Communities: Jewish, Latin, and Balkan Mixed Together

The 16th century marked major shifts in Jewish demography. In the wake of the expulsion from Spain (1492) and the forced conversion in Portugal (1497), Jews wandered eastwards around the Mediterranean basin. About 200,000 Jews found refuge in the Muslim-ruled Ottoman Empire, which at the time, extended from the Balkan regions of Europe to the vast lands of the Fertile Crescent. As a result, cities, which had little-to-no Jewish population, such as Constantinople and Salonika, became significant centers both demographically and spiritually.

A sizable group of deportees also arrived to the land of Israel, then a province in the Ottoman Empire, and settled mostly in Jerusalem. Since the expulsion created an acute theological crisis, many sought resort in apocalyptic beliefs. Jerusalem was, therefore, the ultimate destination for those who connected their plight with the arrival of the Messiah.

In addition, to those who came directly to Jerusalem, a constant flow of Jews migrated towards Jerusalem from the Balkans and present day Turkey throughout the late 15th and 16th centuries. Therefore, by the mid-16th century, the number of Jews in the city doubled. New Sephardic synagogues were established inside the walls of the Old City, and these attracted well-known rabbis and scholars, such as Rabbi Ovadia Bertenura and Rabbi Solomon Sirili.

Little by little, the immigrants from Spain and the Ottoman Empire evolved into a community known as the Old Sephardic community in Jerusalem. This community prided itself for being Sephardim Tehorim–Pure Sephardic– direct descendants of the glorious community from Spain, which generated some of the greatest Jewish philosophers and poets. Being extremely connected to their heritage, the community zealously maintained the religious practices and language called Ladino, a blend of medieval Spanish with some Turkish and Arab words, written in Hebrew script.

(Above- a Sephardic family in the mid 19th century)

The Ladino speaking community, also known as the Spanyolitim, saw itself as the elite of the Jewish society in Israel. They negotiated with the Ottoman officials and the Muslim populaition in the country. Many of them were merchants, who traveled to other cities in the Ottoman empire - mainly Beirut and Damascus- to import goods. Given their socio-economic status and their attempt to keep their lineage unmixed, the Spanyolitim refrain from marrying outside their community. Marital relationship with the Ashkenazi community was banned, and even engaging with other groups within the Sephardic community (such as the Mograbim,the North African Sephardim) was unacceptable. Wedding celebrations, as well as other communal gatherings, took place in the four Sephardic synagogues in the Old City.

(Above- Yochanan Ben Zakai Sephardic synagogue in 1927)

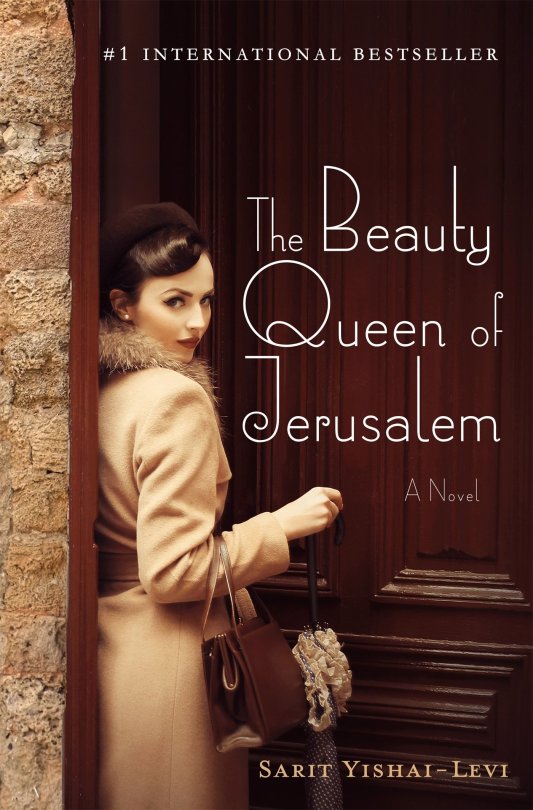

The thread of keeping a tight and pure community is in the center of the novel the Beauty Queen of Jerusalem by Sarit Yishai Levi. The story takes place in the late 19th century and early 20th century and it centers the Armosa family - an archetypical old Sephardic family: well to do with a prominent ancestry. The older son, the handsome Gabriel, is the promise and pride of the family. However, much to his parents' dismay, Gabriel falls in love with an Ashkenazi Ultra-Orthodox woman and attempts to elope with her.

At this point, the story very much resembles a famous Jerusalem’s love tale between Itamar Ben Avi and Leah Abushdid occurring in the mid 19th century. Ben Avi, the grandson of Eliezer Ben Yehuda, the father of modern Hebrew, was madly in love with Abushadid, a member of a distinguished Sephardic family. After years of persistent courting, Abushadid’s family finally gave its consent to the Shidduch, and the couple -at least as told- had a long and happy marriage. This love story became material for songs and novels in Israeli culture, but more so paved the way for “mixed” marriages.

Unfortunately, in the book The Beauty Queen of Jerusalem, the end is far from being happy as Gabriel’s plan to escape ends in a fiasco: the death of his father from shame and grief. Guilt stricken, Gabriel returns to his mother’s house. Furious, his mother decides to teach Gabriel a lesson: a bad Sephardic Shidduch is better than a love based arrangement with someone “who is not one of us.” Accordingly, she forces him to marry the poor and unattractive, yet Sephardic, Rosa. From this point on, the motif of community pressure and unhappy marriage keeps echoing as the plot develops.

The novel walks the reader through some of the historical landmarks happening in the Sephardic community at the time. The first eminent one is the process of relocating outside of the Old City, known in Jewish history as “leaving the walls.” Given the poor sanitary conditions in the Old City, the Armosa family, like many other Sephardic, Ashkenazi, and non-Jewish families, moves outside of the Old City into a new neighborhood. The then new and today famous and classic neighborhoods, such as Yemin Moshe, Mishkenot Shaananim, and Ohel Moshe played an important role in shaping the unique landscape of modern Jerusalem as well as speeding social changes, westernization, and modernity among these old communities. Another important development described in the book was the loss of supremacy to the Ashkenazi Jews, given the massive immigration waves from Eastern Europe throughout the early to mid 20th century. At the beginning of the book, Gabriel is portrayed as a strong, business savvy, and revered young man, but as the novel prolongs his health and businesses deteriorate, and he is incapable to find his place in Mandatory Jerusalem, where Ashkenazi Zionist activists set the tone. The analogy created through Gabriel’s character tells the sad story of many other Sephardic notable men, who were pushed aside and disregarded by Ashkenazi dominated Zionist leadership.

Beyond tragic love stories and unfortunate historical development, The Beauty Queen of Jerusalem is a celebration of Sephardic culture and especially food. Dishes mentioned in the book, such as Sofrito and Avikas con Aroz (bean stew with rice) brings the reader back to Medieval Spain. But Sephardic Jerusalem food has more than a Spanish accent. Inevitably, Sephardic cooks incorporate ingredients used in the local Palestinian cuisine such as fresh sheep milk cheeses, garbanzo beans (used for hummus and other dishes), and lentils, into their home kitchen. Emulating their Muslim neighbors, they served their bitter coffee with overly sweet pastries and even added tamarind sauce to various dishes to obtain the sweet-sour flavor that is so prominent among the Spanyolitim. Another component in the Sephardic Jerusalem cuisine is the Balkan-Turkish influence brought by the Sephardic Jews, who lived in other regions of the Ottoman Empire before settling in Jerusalem. Dishes, such as Burekas filled with feta cheese, spinach, and Stoletch–rice pudding with dried fruit– are examples of the Balkan impact.

Perhaps the most important characteristic of Sephardic cuisine is resourcefulness. Living in a city that underwent numerous conquests, destruction, natural disasters, and famine, the Spanyolitim learned the hard way how to source and prepare a wholesome meal with the local flora. In fact, it is said that during the siege on Jerusalem in 1948, in which the city suffered from great deficits, Sephardic women made bread, patties, and even omelets from Mallow, a local wild plant. Okra is another example of a vegetable popular among Spanyolit cooks as it is local, versatile, and nutritious. The traditional Sephardic way of cooking okra with acidic tomato sauce helps to diminish its texture, and highlights its nutritional value and flavor. Ironically, after years of having a bad reputation as a “grandma food,” Israeli chefs and dieticians are now embracing this vegetable and the Sephardic way of cooking it.

Okra in Tomato Sauce

Ingredients

3 cups of fresh or frozen okra

1 onion shredded in food processor

2 big tomatoes crushed

1 clove of garlic sliced

3 tbsp of olive oil

1.5 tbsp of sugar

2 tsp of pepper

Salt

½ cup of water

Juice from ½ a lemon

Making

Trim the edges of the okra

Warm the oil in the pan and add the onion, garlic and tomatoes. Once boiled, lower the heat and cover the pan.

Add the okra and the rest of the ingredients (except the lemon). Cook until softened but not mushy.

Squeeze some lemon before serving.

Serve warm with rice or any other grain.

Uzbekistan

The Uzbeki community –known in Israeli as the Buchari community– in Jerusalem might be a tiny fragment of the overall population but it is a notable one. The Bucharim arrived in Jerusalem in several immigration waves from 1890 to 1914. The Russian conquest of Uzbekistan stimulated many to leave and because the community was observant by nature, Jerusalem was a natural choice for resettlement.

Originally, the first Buchari immigrants opted to buy land in the Old City. However, the harsh living conditions behind the walls in addition to their needs as a young and culturally and linguistically unique community drove the Bucharim out to search for their own space. In 1894, after several years of community fundraising, a lot was purchased northwest of the Old City. The new immigrants initially named their new space Rechovot (meaning streets in Hebrew) but it was soon known by all as Shchunat Ha’Bucharim or the Buchari Quarter. Eager to replicate their old community life, the Bucharim hurried to establish communal facilities, such as a senior living home, orphanage, and several synagogues, including the Mosayof synagogue named after the community spiritual leader Rabbi Shlomo Mosayof. In addition, a Talmud Torah school teaching in both Hebrew and Parsi was founded to solve the language barrier problems that young Buchari boys were experiencing when visiting schools in other communities. Unlike other new Jewish neighborhoods at the time that were built simply and in a haste, much thought and funds were put into the urban planning and architecture in the Buchari Quarter. Given the generosity of the wealthy members, the facades of the buildings were embellished with Jewish Stars and other decorations, trees were planted on the side of the roads, and empty lots were allocated for farming. Considered then exotic within the Jerusalem landscape, the quarter attracted visitors from within and outside of Jerusalem to admire its beauty and to explore its vivid community life.

(Above- The Davidof family, one of the most prominent families in the Buchari community, a portrait from the early 1920′s)

Today, Shchunat Ha’Bucharim is still a popular destination and several of the sites are protected by the Israeli Council of Historic Preservation. However, given various demographic and political shifts, the original Buchari population shrank and because of this, many of the structures suffer from neglect. As the quarter borders with Jerusalem’s Ultra-Orthodox residential complex, there is an increasing “invasion” of young Haredi families who cannot find housing in their overpopulated neighborhoods. The growing Ultra-Orthodox presence also impacts the moderate religious nature of the Buchari community, as shown in the Israeli film, The Women’s Balcony.

(Above- a street sign in the quarter)

(Above- an example of the Buchari’s quarter unique architecture- the Davidof “Palace”)

The Women’s Balcony (directed by Shlomit Nehama and Emil Ben-Shimon, 2016) is the story of the small but devoted community of the Mosayof synagogue. The men in the community compose a loyal Minyan, and take care of the synagogue maintenance. However, their wives are the burning candle, and the real power behind the joyous life cycle, holiday celebrations, and the community aid. One day, this peaceful life is disrupted. The synagogue ceiling collapses during a Bar Mitzvah ceremony, where the rabbi is badly injured and the structure itself requires serious work. Puzzled by this accident, the men in the community accept the authority of a young charismatic rabbi as their new spiritual leader. The new rabbi is indeed very knowledgeable and committed to repairing the damage, but his religious views are far more radical and do not match the community’s long tradition of religious moderation. The women are the first ones to be affected by his strict agenda. They are excluded from worship and are blamed for being overly permissive when it comes to modesty and Jewish laws. Caring deeply about their community, the women decided to fight back. For more on their struggle, watch the movie on Amazon prime video.

(Above- a scene from the movie)

Although food is not the focal point of the movie, many of the scenes take place in Shuk Machne’ Yehuda, a traditional Middle Eastern Marketplace that is a destination for pre-Shabbat shopping as well as culinary tourism. Zion, one of the characters in the movie, is the owner of a spice store in the Shuck, and is also famous for making delicious fruit salads using fruit from the nearby stands. And indeed, as the movie portrays, the Buchari cuisine very much relies on the use of local and fresh produce as well as aromatic seasonings. Given Uzbekistan’s location in central Asia on the Silk Road, the Buchari food incorporates Russian, Turkish, and Iranian influences. The result is a cuisine that has bold flavors and rich seasonings. Lamb is the favorite meat, and its fat alongside some herbs and leafy green vegetables are highly used to flavor foods. Accordingly, the traditional dishes are Manto- meat dumplings with vegetables and Legman soup made with noodles, lamb and fresh veggies. Similar to the Iranian cuisine rice is the wide-used grain. Bachash, the traditional rice, has many variations from a green one with cilantro, dill, and spinach to a simple white version with thin noodles (or orzo in this case) at the bottom. The movie shows a quick glimpse of a basic white Bachash, and therefore this is the recipe I chose to highlight.

The recipe for Bachash is taken from the book Jerusalem. Palestinian chef Sami Tamimi and Israeli chef Yotam Ottolenghi pay homage to their hometown while curating a plethora of recipes from Jewish, Muslim, and Christian communities. Their seminal groundwork into the Jerusalem cuisine truly helps with understanding the different influences and flavors that make Jerusalem a synonymous name for unique yet comforting food. The beautiful photos, as well as the interesting historical and cultural segments, make this book a nice possession even if not used for cooking.

Unlike many dishes in this book (or in other Ottolenghi’s books), this rice recipe is extremelya to make and does not require any speciality ingredients. My rice recipes are usually taken from the Persian cuisine, which requires longer cooking time and prep. When I made this dish, I was pleasantly surprised how incredibly quick and easy was the process without compromising the texture and flavor.

White Bachash

Ingdientes:

1 ⅓ cup basmati rice

1 tbsp ghee (or butter)

1 tbsp sunflower oil

2 ½ cup chicken/ veggie stock

1 tsp salt

½ cup orzo*

Process:

Rinse rice and soak it for 30 minutes in cold water. Drain and rinse again.

Melt butter and oil on medium heat in the pot.

Add orzo and fry for 3-4 minutes or until orzo turns dark golden.

Add the stock , bring to a boil, and cook for 3 minutes.

Add the drained rice and salt, bring to a gentle boil, stir once or twice, cover the pan, and simmer over low heat for 15 minutes. Try not to uncover the pan- keeping it closed helps the rice to steam properly.

Turn off the heat, remove the lid, and cover the pot quickly with a clean kitchen towel. Place the lid back on top of the towel, and leave for 10 minutes.

Fluff the rice with a fork before serving.

* I used GF chickpea flour orzo, which I think added a nice flavor to the rice.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Moroccan Jewry: Magic in the Claypot

In the northwestern tip of Africa, nestled between the Saharan desert in the south and the Iberian Peninsula in the north, once lived the largest Jewish community in the Arab-speaking world. Morocco, on mountainous terrain, and coastal cities, on the Mediterranean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean, were the ancient homes of a diverse and incredibly vibrant community. And unlike other Jewries in the Muslim lands, which ceased to exist soon after Israel’s Independence in 1948, there is still a fairly sizable community in Morocco, residing in the urban centers of Fez, Marrakech, and Casablanca.

(map of Morocco)

But even outside of Morocco, descendants of this great community who today live mostly in Israel and France, still keep strong ties to their old diasporic home. They are proud of their rich heritage and they zealously preserve their old traditions. The Jewish Moroccan legacy is particularly unique within the spectrum of the Jewish culture, and for that reason, it fascinates many ethnographers, historians, artists, and film directors. Evolved in the diverse geopolitical landscape of Morocco, the Moroccan folklore includes rituals and ceremonies that essentially do not exist in any other Jewish community. Perhaps, the most famous one is the Mimoona holiday –a post Passover celebration of sweets and music– that recently regained the status of a national holiday in Israel. More about the unique rituals associated with the Moroccan Jewry are later in this post.

(Traditional food and garments in a Mimoona celebration in Israel)

One of the most interesting things about Moroccan heritage is the marriage between Torah and sorcery. In other words, the important role of Jewish scholarship and the revered role of rabbis did not diminish or even contradict the strong folklore and the plethora of ancient spells, charms, and all sorts of witchcraft associated with it. In many cases, these two forces went hand and hand, and the rabbis not only validated these popular beliefs but also took an active role in cultivating them. In that respect, rabbis addressed issues of how to remove an Evil eye (a gaze or stare superstitiously believed to cause material harm) or instructed to install a Hamsa (amulet symbolizing the Hand of God aimed to keep away grief and bring in prosperity) in one’s entryway. Many rabbis participated and encouraged the practice of Martyrdom, including raising popular rabbis to the degree of a Tzakik or a Kadosh (a saint), and attributing supernatural powers to him. A major part of this tradition was the graveyard worship that included a pilgrim to the martyr’s grave, and collective or individual prayer on-site.

(The grave of Rabbi Amram Ben Diwan in Ouazzane)

The “magical” world of Moroccan Jews definitely transmitted into the realm of the kitchen. Moroccan cuisine is aromatic and flavorful. It utilizes the many spices and legumes available in the region and blends them into a rich distinct taste. The last section of this entry will elaborate more on a specific dish that encompasses many of the Moroccan flavors. But first to better understand the influences on the food (and culture in general), here is a brief historical review.

2000 Years of History in a Nutshell

According to archeological evidence, Jews resided in Morocco, mainly along the coast, as early as the second century CE. Historians assert that Jews were motivated to migrate to this area given its commercial potential as a connecting point of the two sides of the Mediterranean. The mercantile function that Jews filled up from this early stage of history became a thread throughout centuries of Jewish settlement in Morocco.

A pivotal phase in the history of the community occurred in the 15th century as deportees from the Spanish inquisition first arrived to the shores of Morocco. Although information about numbers is insufficient, it is clear that the Iberian refugees were a sizable group within the local community and even the majority in several cities. At first, the newcomers from Spain and Portugal and the locals operated in two separated communities. They worshiped in different synagogues, followed only their rabbis' authority, and resided in different parts of town. Their relationship was also affected by commercial rivalry and language barrier since the Megorashim (Hebrew for deportees) spoke Ḥakétia- a mixture of Spanish, Hebrew and an Arabic dialect- and the native community conversed in Judeo-Arabic, which was basically the local dialect infused with some Hebrew words. Gradually, the two communities bridged their differences and consolidated into one Jewish community. An important landmark in this process was the writing of the Jewish laws book of the city of Fez in 1698, which was a collaborative effort of religious leaders from both sides to find common ground. The Fez precedent was later fostered in other towns in Morocco, and it became the religious codex followed by the entire Moroccan community to this date.

(Jews in Fez during the 20th century)

In Morocco, as it was in other places in the diaspora, Jews were frequently subject to the temper and political agenda of the local ruler. Generally speaking, in the pre-modern era the Moroccan Jewry lived relatively peacefully and maintained good relationships with their Muslim neighbors. Yet, in certain periods the Jewish community suffered from brutal persecution. A particular painful chapter occurred during the late 18th century under the reign of Sultan Yazid. The latter ordered the slaughter of wealthy community members, and forced others to convert. In addition to occasional violence, Jews in Morocco were also defined as Dhimmis- second class citizens. Under this definition, Jews were granted freedom of worship but were subjected to additional tax and other,often humiliating, restrictions.

Colonialism influenced the history of Moroccan Jews in the 19th and first half of the 20th centuries. North Africa, in general, was an important battleground for the European superpowers and Morocco -as a result- was split between French conquest in the majority of the land and Spanish occupation in the Northern region of Tangier. The French presence was not merely physical or administrative, it opened the door to modernity and European influence. Overall, Jews, particularly those residing in the big coastal centers, were enamored by French culture. Many gain fluency in French, and indulged on French literature and treats. However, only a small affluent elite was guaranteed with the privilege of French citizenship. The majority of the local Jewry was categorized as subjects with limited rights in the colonial rule.

(Moroccan Jewish woman in traditional clothing, circa 1920′s)

In addition, the French rule did not improve the socio-economic status of the local Jewry. Most Moroccan Jews lived fairly meagerly in crowded neighborhoods, called Mellah. Others lived in villages among the Berber population. Craftsmen and small scale retailers were the common trades among men. Women stayed home and ran the household. Boys were sent to Jewish school, named Kutab -a system of schooling similar to the Eastern European Heder- in which the emphasis was Torah study with very little secular education. Only a minority sent their children to private French schools or to the Alliance schools, a Jewish international school network with a strong French orientation. Nevertheless, one should not underestimate the importance of Jewish scholarship among Moroccan Jewry, who generated high numbers of Rabbis, poets, and Talmudic scholars.

(Typical Kutab in Marrakech)

(The Mellah in Meknes)