This is where I'll post everything regarding my writing! You can find my main blog at @definitelynotclayface

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

most of y'all probably already know about this website, but if you're a writer and you're looking for names for your characters (especially ones that fit a particular theme) might i recommend magic baby names?

you can enter one (or multiple) names and it'll automatically generate names that are thematically similar to the one(s) you gave them, which can be SO HELPFUL when you're looking for inspiration

12K notes

·

View notes

Text

A Simple Structure to a Compelling Story

(@punkrocksherlock on Instagram)

So, you're early in your passion for writing, the pencil's just tapping the paper and you're not quite sure exactly where to drag your protagonist to next. Not to worry! Thankfully, Dan Harmon's Story Circle has saved me more than once when it comes to structuring a whole, coherent plot with a satisfying payoff.

It's a very basic structure of only 8 steps:

A character is in a zone of comfort - Here is where your protagonist is established so that your audience can root for them in their journey; the easiest way for that to happen is for your audience to relate to your character. It only takes unfortunate happenings, personal ambitions or anything remotely human for any human being to relate to it.

But they want something - Your character may not be in total satisfaction with their zone of comfort or they may be pushed slightly outside their zone of comfort and thus want something in order to return. Your character may even refuse the call to adventure several times before something compels them to accept it.

They enter an unfamiliar situation - This is where your protagonist crosses the threshold and steps into a world of chaos. Their adventure has just begun.

Adapt to it - Your character will continue delve deeper and deeper into this abyss of chaos; they will encounter obstacles, solve a few, but encounter more. Anything that was once deemed important no longer is except for the new skills they're learning along the way.

Get what they wanted (although perhaps 'it's not quite what they were looking for') - At last, your protagonist has a moment to breathe. Whatever the thing is, good or bad or both, they finally have it. It's a break from the constant struggle; but this break is not to last for long since - as Dan Harmon states - 'This is a time for major revelations, and total vulnerability'.

Pay a heavy price for it - Things haven't gone the way they were planned. Give your character a moment to relfect (including upon their previous behaviour), to evaluate the options given and to decide which one will lift them up from the depths. There is now a more personal or honest call for what they now want.

Then return to their familiar situation - The penultimate phase. Your protagonist will now take what they've learnt and everything they've gained on the way to their final goal. It's a similar type of path they've found themselves on before but this time something's different. This time, there's a sense of reformation, stability, and order.

Having changed - The final showdown. The one piece of conclusive evidence. The beginning of a rebuilt relationship. Your character is ready for the climax because they have changed.

You may be able to use several story circles within the same one story and you can even omit certain elements of the story circle to subvert conventions; whether you're capable of doing this effectively is down to your skill. But as Dan Harmon himself concluded, 'It doesn't matter [...], you know the answer instinctively. You know all of this instinctively. You are a storyteller. You were born that way'.

653 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Horror Beat Sheet

There are no hard-and-fast rules in writing fiction. There are, however, some established patterns and expectations, and once you know them, you’ll be able to work within those patterns and deviate from the path as you see fit.

What is a Beat Sheet?

Popularized by Blake Snyder’s book Save The Cat, beat sheets are an outlining method often used for screenwriting that some authors have started to use for books as well. Basically, a beat sheet lays out the story ‘beats’ or necessary plot points that make up the essential story structure. The Hero’s Journey is, essentially, a beat sheet. You can see more beat sheet information here: https://timstout.wordpress.com/story-structure/blake-snyders-beat-sheet/

Horror has a slightly different structure than other stories, and for that reason I don’t think a classic beat sheet works quite right for it. So with that in mind, here is my somewhat adapted version, drawn from my studies of horror media. Various beats can be reorganized somewhat, and will vary a bit depending on sub-genre and other considerations. But if you need help in establishing a horror plot…this beat sheet should help guide the way.

Horror Story Beat Sheet

Act One (The Setup):

1 - The World is Not What it Seems

(The reader catches an early glimpse of the monster, or a hint that the monster exists. This is optional, and may occur right away – often as a prologue – or after the main characters have been introduced.)

2 - Putting the Players in Action

(You introduce the important characters and the primary internal conflict)

3 - Setting them on the Path

(The characters make a choice that inadvertently isolates them or places them on a collision course with the monster)

4 - The Warning

(The characters are given an opportunity to turn back, but choose not to; could occur before or after The First Contact With The Monster.)

5 - The First Contact with the Monster

(The characters have their initial contact with the monster, but are unaware of the true threat it poses.)

Act Two (The Turn): 6 - Shit Gets Real (May be the first death or when seriously spooky activity begins; regardless, this is when the danger becomes evident and unavoidable)

7 - The Chase (The monster pursues the characters, who lack the skills to fight it; one or more people may die here)

8 - Failed Confrontation (The main character attempts to destroy the monster, but does not yet possess the ability to do so)

9 - The Darkest Hour (Hope appears lost. Perhaps someone very important has died, or the hero has tried everything they can think of. The link between the internal conflict and monster may become clear to the character here)

Act Three (The Prestige): 10 - A Different Solution (The hero gains new information on how to defeat the monster. This may be delivered by someone they seek out for help, or may come through soul searching and observation.)

11 - Seeking Out the Beast (For the first time, the hero approaches the monster, rather than fleeing it. They intend to enact their solution)

12 - The True Cost is Revealed (In the process of confronting the monster, the hero realizes that to overcome it, the internal conflict must be encountered and defeated. That is the hidden cost; the hero will be irrevocably changed)

13 - Sacrifices Are Made (or not) (Faced with the ultimate choice, the hero either succeeds in defeating their internal conflict and winning against the monster, or fails and ultimately succumbs to their weakness)

14 - The Inevitable Fall Out (Show the consequences of whichever choice is made)

15 - Evil Cannot Be Conquered, Only Delayed (If the hero failed #13, show the monster relishing its victory in a changed world. If the hero succeeded, show a hint that the monster may yet return. )

—- I think you will find that if you compare many, many, many horror stories against this beat sheet, you will see versions of this structure/pattern. I encourage you to try it. I’ll post some plot studies of my own to show you later.

There is no single “right” way to write a story, and I certainly don’t think you must follow this structure in order to be successful. But I can guarantee you that following this structure will give you the framework necessary for a complete and emotionally satisfying horror story.

Caveat: this beat sheet is meant for long-form stories such as novels and films. Short stories follow a very different structure. We can talk about that in a later chapter.

If you like this type of content and would like to see more, please consider leaving a tip in my Tip Jar!

1K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Every* scene should have a climactic moment or turning point–either a revelation or an action (those are the only two things it can be). *Well, all rules can be broken.

Scenes that all build together toward a bigger turning point, form a sequence.

Sequences fit within an act, which has an even bigger turning point.

Acts fit into the overall plot, which has THEE climactic moment or turning point. (This means that at least the beginning, middle, and end, all have climactic moments.)

639 notes

·

View notes

Text

Writing Psychotic Characters

Hi! I’ve seen a few of these writing things pop up recently (and in the past), but I haven’t seen any on psychotic characters—which, judging from the current state of portrayals of psychosis in media, is something I think many people* need. And as a psychotic person who complains about how badly psychosis tends to be represented in media, I thought I’d share a bit of information and suggestions!

A lot of this isn’t necessarily specifically writing advice but information about psychosis, how it presents, and how it affects daily life. This is partially purposeful—I feel that a large part of poor psychotic representation stems from a lack of understanding about psychosis, and while I’m not usually in an educating mood, context and understanding are crucial to posts like this.

Please also note that I am not a medical professional nor an expert in psychology. I simply speak from my personal experiences, research, and what I’ve read of others’ experiences. I also do not speak for all psychotic people, and more than welcome any alternative perspectives to my own.

*These people, in all honesty, aren’t likely to be the ones willingly reading this. But there are people who are willing to learn, so here’s your opportunity.

(Warnings: Mentions of institutionalization/hospitalization, including forced institutionalization; ableism/saneism; and brief descriptions of delusions and hallucinations. Also, it’s a pretty long post!)

Keep reading

655 notes

·

View notes

Text

i’ve been doing my homework on how to break into a writing career and honestly. there’s a Lot that i didn’t know about thats critical to a writing career in this day and age, and on the one hand, its understandable because we’re experiencing a massive cultural shift, but on the other hand, writers who do not have formal training in school or don’t have the connections to learn more via social osmosis end up extremely out of loop and working at a disadvantage.

162K notes

·

View notes

Text

Killing off characters: the shoulds and shouldn’ts

1. Why you should

The death is a major plot point

It reveals some shocking plot twist

It supports your themes/what you’re trying to say with your book

Your novel explores the afterlife

You are George R.R Martin and the selling point of your work is that everybody dies

It suits the genre/mood of your novel

2. Why you shouldn’t

The character isn’t serving any purpose (this isn’t the Sims)

You want your readers to be shocked for the sake of being shocked

You want to be edgy

You think your MG story needs more gore

You want to romanticise grieving/loss

3. How you should

This really depends on your genre and target audience

If you’re writing something that isn’t intended to be graphic/traumatic, you can stick to the impact the death has on the other characters. If your novel explores illness, focus on that rather than on the disturbing death scene itself. Perhaps you’re writing a drama/tragic romance - you might want to ease up on the gore here. For these genres, I would suggest focusing on the emotional aspect of the death - the sobbing, the last words, the bright white lights (whatever floats your boat). Think of Mufasa in The Lion King - the actions are suspenseful, but we don’t see him being trampled with his guts spilling everywhere. But it’s still one of the most impactful deaths in fictional history.

If you’re writing in a more mature and gritty genre (like thriller, dark fantasy or crime), you can go all out. If there’s blood and guts, you readers probably want to see it in vivid detail to get their violence fix for the day.

Whichever genre your novel falls into, you should also go with what feels comfortable to you. Even if you’re writing adult dark fantasy, you don’t have to write graphic violence to make a character death impactful.

4. How you shouldn’t

Please don’t let your character have a three-pages-long monologue after they’ve been stabbed in the throat. It’s not realistic and it’s often very boring. Yes, a few well-written last words can have a great impact. Just make sure that your character would realistically be able to speak at that point and that it doesn’t become a cheese fest.

Unless you’re aiming for very dark/nihilistic humour, afford your characters some dignity in the way they kick the bucket. (e.g. don’t use the phrase “kick the bucket”). Having someone slip on a banana peel and then choke on a pretzel is a little ridiculous and will make the entire story seem silly. Once again, this really depends on what you’re going for. If your genre is serious and your character is important and beloved, try for emotion rather than whimsy.

Don’t let your characters die only to be resurrected again and again and again. Look, I love Supernatural (long may they reign), but even I have to admit that the Winchester brothers’ luck with death has become a bit ridiculous. Doing this takes away from the impact of the death - it removes the fear and suspense, and will leave your readers emotionally stunted.

5. Who you shouldn’t

Your only female character in a bid to make the male hero feel something and become a better person

Your only LGBTQIA+ character, who is just too pure to live in this terrible world

Your only character of colour, who dies to save the white hero

Your only disabled character, who can now finally find release from life with disability

The one character who has never experienced a sliver of joy and bears the brunt of the tragedy, right when happiness is finally within their reach

The main character in the middle of the story - unless you have a REALLY good plan for what happens next

Reblog if you found these tips useful. Comment with your own thoughts on killing off characters. Follow me for similar content.

19K notes

·

View notes

Text

How to Outline Effectively

– Outlining is a fairly important part of writing a longer story, especially full novels or even series, so I figured I’d create a guide to making an outline that is actually useful during the writing process so writers like me, who are more likely to write if they have a solid plan, will feel less lost.

Outlining is surprisingly hard, and nobody does it exactly the same way. There’s no one right way to do it, but this is what is the most helpful to me and hopefully this article will help you understand what the true purpose of an outline is, how to create one that’s actually useful, and how to get everything you possibly can out of it.

Purpose Of Outlining

First, I must specify that, in this context, an outline is not simply a summary of the course of events within your story. It is also a detailed plan that will guide you in your writing process. An outline allows you to enter the task of completing a first draft with a good to fair chance of eloquently intertwining all of the essential elements of your story. Many authors do commit to creating an outline, but not an effective one.

Not only should an outline provide a timeline for events of the story, but lay out a base plan for the execution of symbolism, orchestration of character and conflict development, introduction of world-building elements, and premeditate the domino effects that plot points will cause, whether to the main plot or subplots. These details make an outline useful, or at least more useful than the alternative, which only explains what happens without giving the Why or the How.

What To Outline

When it comes to creating an effective outline, it is important to remember that it is for you. You are free to create an outline that includes all or some or none of the things listed below. However, your story will include every single one of these things, and whichever ones are not planned beforehand will be more likely to challenge you when it comes to writing the actual draft.

Events

This one is fairly obvious, but I have some additional suggestions when it comes to creating a timeline of the events occurring in your story.

Outline the plot progression and the subplot progression. It’s helpful to outline these on the same timeline so you can see where subplots begin and end parallel to the main plot. I recommend color-coding to create a visual of your storylines.

When you plan an event in your story, make sure to specify why that scene is included and what purpose it will serve, to its corresponding subplot and the main plot overall.

Limit the amount of large events and small events that can occur. You should be able to determine which is which. I try to limit myself to 30 events total, or 10 main events and 20 smaller ones that build up to the larger. This isn’t a rigid limit, but it keeps you from biting off more than you can chew. This may seem like a lot of events, but smaller events can be things like a discussion between two characters or a scene in which a character is, say, driving to work and inwardly reflecting on something that recently happened.

It’s important to remember that more than one event can take place in a single scene. An event does not equal its own scene. Do not organize your timeline by scene. You will end up writing your story scene by scene rather than event by event, and you will regret it, because when you start telling a story based on the place it happened and when, you’ll leave out details and will be more likely to neglect opportunities to utilize subtext and symbolism.

Symbolism

Symbolism is not paid much attention when it comes to writing things outside of an educational environment, but it shows up in writing, whether intentionally by the writer or not. However, intentional symbolism adds depth and context to your story that cannot be obtained in any other way. Meaning and emotion are conveyed through symbolism, and your story will suffer if you don’t give it at least some of your time. Here’s some things you can do and some things you should remember when you’re outlining symbolism:

Find opportunities for symbolism in your story and utilize them to the best of your ability. If you want your character to have an object that they can’t live without, connect that object to something important that has happened in their life or make it symbolize a value they hold above all else or a belief that they will never abandon.

Symbolism is best used to develop three things: plot, character, or background.

Symbolism is best conveyed through objects, smaller events, rules, or relationships.

Specify the reason the symbol is being included in your outline. If you’re adding a symbol just so you can say that there is symbolism, you’re doing it wrong. Symbols should teach the reader something or convey a message to them, and if it does neither, don’t include it.

Development

Planning out the development of your conflict, characters, and theme of your story is one of the hardest parts of outlining because it’s not always possible to predict how your characters will turn out. Writing is a weird, personal, unpredictable process and sometimes our conflicts, characters, and themes end up developing on their own. However, it’s good to have some sort of idea what points A and B are, and which points are between them.

Conflicts develop mostly through a mixture of smaller, less significant events, and slow burning feelings that eventually bubble up in the climax. Those smaller events need to build up nicely to that climax. If you neglect this, it will result in lack of suspense due to no emotional building. The climax should feel like an explosion in the reader’s chest, not a leisurely stroll through a boring park.

Your character will be developed in the reader’s minds through the three main things we remember about a person: their actions, their words, and the way they present themselves outwardly. Any or all of these things may change over the course of the story, and that’s where the development will reveal itself. Your readers may empathize with your characters’ thoughts and feelings, but they won’t remember that as much as the three things listed above. Focus on planning the development through those three areas.

It’s very nice to have an outline that has detailed the plan for conveying the theme of your story. This is very easy to forget about while actually writing, and one or two footnotes about “This character’s action connects to the theme of subtle racism in America, because this gesture they’re described as using relates to a historical reference of blank blank blank” etc. can help a lot. Find several clever little ways to sprinkle in your theme throughout the book, but be intentional and very careful, because your theme is the easiest thing for critics and nitpickers to get snippy about.

Allow room for your story elements to develop on their own during the process. However, be aware of when these details stray from the original plan and think critically about them, because little changes can completely screw large plans.

World Elements

World building is one of the most fun parts of writing stories, mainly in the science fiction and fantasy genres, but it’s oddly strange to fit in pre-planned details while writing the draft. This is simply because you’re more focused on the plot and development of conflict and characters. There are little ways you can plan time for world development in your outline, though.

Plan short scenes that revolve around or at least rely on the reader learning details about the world, whether that be politics, magic systems, leadership in fictional worlds, or simple details that provide a sense of familiarity.

A good example of this is Harry Potter. JK Rowling is a queen when it comes to world building, and that universe is so fully developed with locations and lore and languages and political systems. Yes, there were seven books, but that’s an astounding amount of information that was never developed in a clunky, information-overload sort of manner. She wrote several smaller scenes where the trio were simply discussing the events within the story and used those opportunities to introduce new locations, items, lore, etc. that created a world that millions still feel is a second home to them.

Remember to continue building the world as you go. There will come scenes where you find little cracks to fit in facts about the world. Use them. Just keep track of those little details in a separate place or something so you don’t contradict yourself later. You could keep a “___ textbook” or something where you organize information about your world so you can either track new details or refer back to things you’ve already specified.

Have rules for your world. Every great magic system or alternate universe in fiction has its limitations, and if you simply say “nope, no rules in this system” your readers won’t connect to the system and world as a whole as wholly and your world-building will be seen as lazy. That’s just the way it is. It’s also a lot harder to create conflict when there are no defined limits or rules in a fictional world or system.

Domino Effects

Every action, expression, or event has its own consequences. Everything in your story will have a ripple effect, and maybe your readers won’t see every wave, but they should feel most of them, and that’s a hugely neglected part of outlining. Anticipate how each scene will affect the plot progression, character relationships, emotions, etc. because readers sense when events don’t connect.

For each scene, specify what led up to it and what it leads to. An example would be, “Steve heard his mother talking to his best friend on the phone, then he drove to his friend’s house to ask him what it was about, then it leads to a fight when Steve finds out his friend and his mom are seeing each other.” This specifies the initiation of the event, the event, and how the event leads to further conflict. You can sense how Steve and his friend and his mother’s relationships will be changed, and how the characters will likely be acting for the foreseeable future.

I prefer to write down the events of my story on a single piece of paper, organized in three sections. The first being cause, the second being event, and the third being effect. This is a simple way to keep track of the domino effects in your story.

Again, you don’t need to plan every single wave that every single event causes, but you should plan how you’re going to include the relevant ones in your draft.

These domino effects are not linear all the time. Effects of some events may not show up until several scenes, or even chapters later. A lot of waves take time to build and then come crashing down at the very end, so keep those in mind too. Plan the long term effects of larger events as well.

How to Utilize Outlines

Outlines are a waste of time if you aren’t going to actually use them to their full potential. It’s also crucial to note that your outline isn’t set in stone when you begin writing your draft. You can and should be adding to and amending your outline as you go along. That being said, here are some ways you can use an outline to aid you while you write you draft.

Keep track of world-building and what limitations may be imposed on your world or characters by details you add as you write.

Use the outline to keep track of how far you are into the story so you can be intentional with foreshadowing and revealing information at the opportune moments.

Have your timeline parallel to your development trackers and sprinkle in moments that show that development.

As you continue writing your story, acknowledge the domino effects in mind so you can set up future events that might need that context.

Create little “symbolism milestones”, so you know when the height of a symbol’s importance shows up in your plot and you can emphasize on that symbol in the actual writing.

etc..

Bottom line is, you can outline however you want and use that outline however you see fit, as long as you’re using your time wisely and creating something that will be helpful to you. My main advice is to just keep the aforementioned elements in mind when considering what to plan for your story beforehand. Happy outlining!

Support Wordsnstuff!

If you enjoy my blog and wish for it to continue being updated frequently and for me to continue putting my energy toward answering your questions, please consider Buying Me A Coffee.

Request Resources, Tips, Playlists, or Prompt Lists

Instagram // Twitter //Facebook //#wordsnstuff

FAQ //monthly writing challenges // Masterlist

MY CURRENT WORK IN PROGRESS (Check it out, it’s pretty cool. At least I think it is.)

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Reblog if you write fanfiction!

Writeblr has a lot of original WIPs which is fantastic, but I want to see how big the fanfiction community is too!

5K notes

·

View notes

Note

Do you have any writing craft book suggestions? I've never taken a professional class and I feel like I'm missing out on understanding some of the mechanics of what makes a story flow

I’ve never taken writing classes either, so I don’t know how much help I can offer. Most of what I know about stories comes from analysing good ones in uni - which automatically means that sometimes when I’m reading a book, I’ll notice when things aren’t exactly right. But applying that to your own writing is, of course, a different matter.

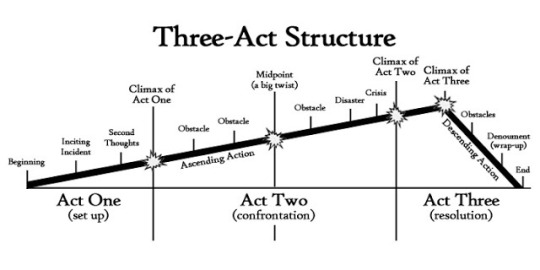

The two books about writing I have on my shelf are Beginnings, Middles & Ends by Nancy Kress and a Collins guide on Writing Fiction, but if you’re wondering how to turn interesting characters and half a plot into a novel, there’s plenty of stuff online as well. Most novels, for instance, use what’s called a ‘three-act structure’ - here is a template.

Something like this can work well for any story, because the nodes can be adapted to what you’re writing. In a romance, for instance, the inciting incident can be a gorgeous guy splashing coffee on our protagonist, while in a thriller it will probably be a murder. Obstacles can be something as ‘mundane’ as a mom grounding her daughter all the way to a murderous merman locking up our heroes in a soon-to-be-flooded cave.

While the three-act structure is very common and generally efficient, there is more than one way to structure a story. You could start by going through the writeblr or nanowrimo tags here on tumblr, or watching online videos, but whatever you do and whatever you learn in theory, I think it’s good practice to start recognizing those things in books you read.

(Plot points, character tropes and story structure are also easy to pick out in movies, especially blockbusters.)

If you want to be a writer, don’t read blindly, just for the sake of knowing how a story will end. Take your time to pause, or re-read a favourite book, and try asking yourself: Why did this work? Why was I shocked or surprised? Why was I expecting this turn of events? Why was I so desperate for them to kiss? This is something I do a lot, usually during a second reading, and I find it very useful. Of course - even when you understand what works, it’s not easy to apply those things to your own writing, but the only way to write better is to write more - there’s no escaping that.

102 notes

·

View notes

Text

Writing advice I don’t agree with

DISCLAIMER: This is my opinion

1. Passive voice is always bad

There are so many tests/checkers for identifying passive voice in your writing and it has become a rule to change every instance of its occurrence.

Why?

Yes, I get that it isn’t as exciting and makes your plot/characters seem passive rather than active. Maybe it doesn’t make for great prose.

But it does have its place.

I think that one/two/five passive voice sentences in a book are fine. Will you really get burned at the stake if you have the sentence “Her heart had been broken” in your manuscript?

Maybe I’m just missing something.

Don’t get me wrong, I’m not saying every second sentence should be passive voice. I’m just saying that you don’t have to change every single passive sentence in your work.

2. Real writers write every day

Listen, I’ve been writing for thirteen years. I’m always working on a project and I take my writing very seriously. I AM a writer. But I don’t think there’s ever been a period in my life where I wrote every single day.

Yes, if you schedule time to write every day and you manage to stick to it, you’re amazing. And you’ll probably be published quicker.

But that doesn’t mean that other writers aren’t serious about their writing or aren’t “real” writers.

Sometimes, life gets in the way. Sometimes, your creative muscles are really tired and all your words come out crappy. It’s normal.

It depends on your energy cycle/other responsibilities/goals. If you are working on your WIP and making progress, you’re a writer.

Don’t be so hard on yourself. Jeez.

3. Only include what is relevant to the plot

I confess: I am an overwriter. My current WIP is looking to be 150k words, so I’m gonna have to do a LOT of cutting in the editing phase. So yeah, maybe I should take this advice.

But objectively, I don’t believe in the strict application of this rule.

If JK Rowling/J.R.R Tolkien only included what would move the plot forward, we wouldn’t have the amazing fleshed-out worlds of HP and LotR. The extra, interesting stuff is what makes those stories so amazing.

So, I think a much better way to think about this is: Only include what is relevant to your CHARACTERS’ LIVES.

If there is something awesome that your characters do/see that people don’t get to experience in the real world, tell the reader about it. If there’s some fantastical element about your world that the character would definitely notice, describe how the character experiences it. Live through your characters in the world you’ve created.

4. Every chapter should end on a cliffhanger

There’s this idea that each chapter should follow a formula: End with a tense reveal/cliffhanger > the next chapter opens with the character’s reaction to said reveal > the middle of the chapter is the mini resolution > the chapter ends with another tense reveal.

This is a great way to structure a chapter. But it gets tedious and overdone if every single chapter follows the same basic steps.

Ending EVERY chapter on a tense cliffhanger will drain your readers emotionally and numb them to the tense points in the rest of the novel. So, give your readers time to breathe and enjoy the less intense parts of your story too.

Have a few chapters that don’t end in absolute suspense.

5. Real writers don’t see writing as a business

“Real” writers are in it for the art. They live apart from the world of mortals and only care about fairy tales and castles in the sky. They are too pure and dainty and creative to concern themselves with something as mundane as money.

You are going to die of hunger.

If you agree with these pieces of advice, good for you. I just don’t.

Reblog if you agree. Comment with the writing advice you can’t endorse. Follow me for similar content.

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

me: okay time to jump into the action scene

me: don’t say it

me: don’t say it

me: don’t say it

me: don’t say it

me: don’t say it

me: don’t say it

me: don’t say it

me: don’t say it

me: … “SUDDENLY”

84K notes

·

View notes

Text

The 8 Point Story Arc

1. Stasis

This is the status quo, what life is like for your character before the story really begins. This could last several chapters, or be implied rather than shown if your story begins in media res. Example: Harry Potter’s life with the Dursleys.

2. Trigger

Synonymous with the inciting incident, this is something that happens to the character that kick starts their journey. The trigger could be bad or good, which could affect the nature of the Quest. Example: Percy Jackson is attacked by a monster on a school field trip, and he finds out that he’s a demi-god.

3. Quest

The protagonist has a quest, and sets out on it. This takes up the middle portion of the story. I think the best example is any of the Percy Jackson books, in which Percy Jackson literally goes on a “Quest” starting about 25% into the book.

4. Surprise

This could be interpreted two ways, either as multiple events that happen throughout the course of middle section, or one event that changes the hero’s quest, or both. In the first interpretation, this would be either good or bad turns of fortune, conflicts, obstacles, and revelations that move the middle portion along. In the second interpretation, this could be something big that clarifies the true nature of the conflict, or lifts a veil for the protagonist, which would likely happen about halfway or two thirds into the novel. You can, of course, have both.

5. Critical Choice

The protagonist’s true character is revealed when they are given a choice. This a monumental moment in a character arc. Their decision reflects the growth that they have made along the journey; they wouldn’t have made the same decision during the stasis. This is often between a good but hard choice, and a bad but easy choice. For instance, the choice between betraying a friend to be one of the cool kids, and the choice to stand up for a friend against terrifying bullies.

6. Climax

The result of the critical choice, and the highest point of tension in the story. Think, Harry Potter facing Voldemort for the final time at the end of the Deathly Hallows. Who will win? Who will lose?

7. Reversal

Things begin to change in the protagonist’s favour and they defeat the final obstacle. Example: Cinderella putting on the glass slipper and proving that she was the girl at the ball. A new status is achieved.

8. Resolution

The ending of the story, in which a new stasis is achieved. This could be several chapters or a few pages in the case of a cliff hanger. Loose plot threads are tied up, and a readers are given a sense of closure.

How to use the 8 Point Story Arc

This story structure has its pros and cons. One pro is that you have a lot of wiggle room with these story beats, and it is a time honoured story structure. The issue, on the other hand, is that they’re also quite vague, which you may not want. Everyone interprets these points differently.

In many ways this story structure works best for short stories, because short stories don’t have a long middle, and the two beats ‘Quest’ and ‘Surprise,’ may be all that you need. But in a novel, ‘Quest’ and ‘Surprise’ may seem rather insubstantial for the middle portion of the novel, which most people struggle the most with anyway.

You can also use this structure on multiple levels, using it to plan your entire book, but also using it to plan chapters and scenes within your book.

If you’d like to read more about the 8-Point Story Arc, read about it in Nigel Watts’ book, Writing a Novel and Getting Published.

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

Writing Villains

I’m a horror writer, which means bad dudes are my bread and butter. But they can be tough to write. Especially when you want them to be interesting and relatable characters (which, let’s be honest, they should be). So here’s a few little tips to help you guys write super cool villains that people may or may not want to bed.

1. Give them a realistic motive.

Most of your evil peeps probably don’t think that they’re evil. They probably don’t call their homes “evil lairs” and they most def don’t call their joy “evil laughter”. In fact, they probably think that what they’re doing is justified. And I’ve always thought it was pretty dang cool when I could actually see their point. So make their aspirations realistic. Make them real people, with good and bad in them. Complex characters are supes exciting.

2. Or don’t.

On the other hand, certain stories call for a villain who is evil for fun. This is entertaining, and can be pretty scary in the right context. I mean, think about it: dude has no redemption, no remorse, and most importantly, no tragic backstory. They have no boundaries, and they aren’t afraid to eat some babies. One of my most favorite characters of all time is one of these kinds of villains, and I have loved his character since the eight grade, just because he is tantalizingly evil.

3. Make them a real threat.

Nothing is more boring than a story where you just know your heroes are going to come out on top. If I know what the ending is going to be within the first three chapters, guess what? I’m putting the book down, and I’m not picking it back up. Like, ever. Conflict is interesting and important. And your protagonists need a serious fight for me to care about their story.

4. Show us a different side of them.

I’m not the biggest Marvel fan (not for any reason, I’m just not). BUT I did see “Infinity Wars” and I gotta say, I liked the way that Thanos was written. He was the big, bad dude. But we also got to see him in a different context at points in the movie. It doesn’t redeem him, it doesn’t make him a good guy, but it doesn’t make him a cookie-cutter villain, either. Let us see the villain cuddle their prized dog. Let us watch her savoring her favorite meal (but not if it’s babies. That’s still bonkers evil, bro.).

5. Stop making the villains monologue 2K19.

Seriously. By the time hero and villain are having their big fight, I should know why Bad Dude is bad. In “Harry Potter” we knew off the bat that Voldemort was wizard Hitler. He didn’t have to tell us. I mean, yeah, he and Harry talked sometimes, but it wasn’t that obvious Villain Speech that we’ve come to know and love (hate). Through the series, we saw the bad stuff he did. We knew what he wanted. And that made their battles not suck.

Anyway. I can’t wait to see what horrifying little meanies your brains come up with. Love you. Bye.

669 notes

·

View notes

Text

Part of me wants to shift the entirety of Magical Fantasy Adventure Land into the normal world instead of splitting it into a separate realm.

Part of me is still annoyed that this fucker still doesn’t have a proper title. Or at least something that sounds better as a place holder.

60K notes

·

View notes

Text

some highlights from my writing seminar with honestly one of my favourite authors of all time who shall remain nameless bc i dont want her to know i was spilling her secrets online

The first trick is to detach yourself from your idea. You don’t have just one novel inside you, and it’s not a big deal if you don’t finish this novel.

She was skeptical of the common advice “just write!!1!” - she talked about how long ideas for her most popular novels were marinating inside her before she properly wrote them

As a continuation of that, she was a big believer in knowing what you want to write before you write it. Not what you’re going to write, what you want to write.

The first thing she decides about a novel is what the mood is going to be, and this informs every other decision (e.g. the mood for Shiver was bittersweet)

Ideas should be personal, specific, exciting and they should exclude secondary sources. A personal idea isn’t necessarily autobiographical (which should be avoided), but it speaks to your emotional truth.

She said she had been read Ronsey fanfiction and she couldn’t view her car in the same way since.

Story is the thing that seems most important to reader but is most changeable to the author - story is subservient to your mood and your message. Change what you like in the plot as long as your book retains its sense of self.

Story is conflict, exploration and change. A good story has active tension -the characters want something, instead of just wanting something not to happen (e.g. wanting to kill an enemy instead of simply defending a stronghold against an enemy)

A story needs to have a concrete end, something to be done.

Satisfaction is important - deliver what you promise to the reader. The other shoe has to drop. Ronan Lynch doesn’t ever talk about his feelings, so its rewarding when he does.

Earn your emotional moments (she threw shade at Fantastic Beasts lmao)

Forcing a character to be passive is dissatisfying to the reader.

Characters are products of their environments, consistent/predictable, nuanced and specific, moving the plot, and subservient to other story elements.

She always starts with tropes for ensemble casts like sitcoms. Helpful for building good character dynamics.

Write scenes with characters saying explicitly what they’re thinking and then go back and make them talk like real people in the edit.

An action can also prove what they’re thinking, instead of making them say it or another character guess it (e.g. Ronan punching a wall).

Move the reader’s emotional furniture around without them noticing.

All her books follow the three act structure. Established normal -> inciting incident -> character makes an Active Decision -> fun and games -> escalation -> darkest moment -> climax.

Promise what you’re going to do in the first five pages.

Read your book out loud. Record yourself reading it.

If you have writer’s block, it’s because you’ve stopped writing the book you want to write. She likes to delete everything she’s written until she gets back to a point where she knew she was writing what she wanted to write, and then carrying on from there.

24K notes

·

View notes