Text

Strata 2023 Photography on reused gravestone.

Public artwork for Uppsala muncipality. Workshop with local pupils using metaldetector. Found objects transfered to photgram on second hand gravestones.

0 notes

Photo

The Conference

1961-2021

A conference about the 5th Situationist summit that took place in in Gothenburg 1961. The meeting in 2021 was conducted at Panorama Hotel which is the same place as in 1961.

Paritcipants

Henrik Andersson, Fredrik Svensk, Göran Hugo Olsson, Andria Nyhage, Saskia Holmkvist, Frida Sandström, Johanna Adolfsson, Mikkel Bolt, Dominique Routhier. Emanuel Almborg, Alexander Ekelund.

0 notes

Photo

Havmanden, The Merman 2021

Online work for GIBCA

57°46'18.0"N, 11°40'29.0"E are the longitude- and latitude coordinates of the wreck of the Danish frigate Havmanden. In Kjällöfjord, slightly north of Björkö, in the northern Gothenburg archipelago, is the uninhabited island Risö, on which I am standing facing north-northwest. On the horizon, I can see Carlstens fortress in Marstrand, with its characteristic shape of a cylinder on a block. Boats pass through the waterway in a north-south direction. I cannot remember how many times I have sailed this route along the coast heading north. Not once have I reflected upon what lies hidden here, at the bottom of the sea. I lower my gaze from the horizon and face the islet situated half a cable length from the peninsula where I am standing. Between me and the islet, somewhere on the ocean floor, is where it lies: The Danish West India Company’s ship Havmanden that ran aground in 1683.

I prepare myself to dive. From the navigational chart, I conclude that it is about 5-10 meters to the bottom. A depth I should manage to free dive, i.e. to dive without air from tubes. From the smooth Bohuslän rock, I slip into the water and put on my fins, I spit into the swim mask, gently rubbing and rinsing it with salt water to avoid misting on the glass. I wind the film forward in my Nikonos underwater camera, lift my feet from the bottom, and allow myself to float into the strait between the islands. The wetsuit provides me with buoyancy, despite my lead weight belt. I follow the cliff’s extension towards deeper waters. Tufts of seaweed and algae sway in the waves. Sunlight is refracted into rays upon meeting the water and here, close by the surface, the colours of the plants are clearly reflected. I stay close to the surface and swim farther away from land. The bottom disappears into a cloudy haze in tune with sloping downwards, and soon enough I see nothing more than a cyano-coloured soup of organic material and sediment dissolved in the water. The sea of Kattegatt now completely encloses me. I breathe through the snorkel and decide to dive. I take a few deep breaths and finally hold it. I turn in a forward somersault until I am upside down vertically in the water. In a swim stroke, I grab hold of the water and pull myself down. I can feel my feet in the air above the water surface, but soon enough they are also submerged. My journey down is reduced by the buoyancy of my body and wetsuit and I kick with my legs to continue. Soon enough, I have become neutrally buoyant, my density is equal to that of the water, I am neither sinking nor rising. One last kick with my legs and I can feel that I am now sinking by myself. The pressure of the water has compressed the oxygen in my body so that I am negatively buoyant. I continue down but I can still not see the bottom.

The story of Havmanden is multifaceted and complex, with resonance in this day and age. It needs to be told in the entirety of events that resulted in the Danish frigate ending up at the bottom of the sea outside of Gothenburg. My dive is an attempt to evoke an image and a position from an underwater environment, from which a historical horizon can emerge.

During the 17th century, Denmark, as well as Sweden, attempted to advance their positions in the evolving colonial era. At the core was the so-called triangular trade, where plantations in America produced raw materials for Europe. The production was based on slave labour carried out by people kidnapped from the African continent. Slave trade and slave labour was exchanged for profit and technological development in Europe.

Denmark and the Danish West India Company had taken control over the Swedish slave fort Carolusborg (Cape Coast Castle) in Ghana and established other forts along the west coast of Africa in order to bring people across the Atlantic to be sold. Sweden was initially unsuccessful with its colonial expansion and Denmark had a hard time establishing and keeping its colony St. Thomas in the West Indies in order. A life with hardship or death awaited the ones that were forced there.

In 1682, a new Governor, Jörgen Iversen, was appointed to oversee St. Thomas and take control over the activities on the island. In the autumn of the same year, the Danish West India Company, with the support of King Christian V of Denmark, equips the ship Havmanden. The aim of the journey was to transport Danish convicts to St. Thomas and then continue sailing to the west coast of Africa to acquire slaves. Thereafter they were to return to the West Indies with the slaves and then redirect back towards Denmark. Onboard the outward journey was material to build institutions on the island, as well as the 120 convicts that were to be forced to work in the Caribbean. Twenty of them were women convicted of prostitution. It is this captive workforce who, for some months, will come to rattle the hierarchies in the Danish trans-Atlantic trade. On January 20 when the ship is in the English Channel, the prisoners, together with the sailors, make a mutiny. The Governor, the Captain, and five other officials are arrested and killed by being thrown into the sea. When the mutineers seize the ship, they sail to the Azores and release the prisoners. The remaining mutineers plan to sail to Ireland to sell the ship, but conflicts amongst them result in some of the mutineers taking the chance to save their own skin and sail back home to Copenhagen. At the end of March, when the ship enters the Kattegatt, they are struck by a westerly storm and the ship is pushed towards the Swedish coast. The ship manages to pass through the tight passage between the islands Hälso-Källö-Hyppeln to then drop ship anchor in an emergency before running aground at Risö.

The alderman at Marstrand has the five mutineers arrested and taken back to Copenhagen. There they are executed by being tortured and beheaded.

During this time, mutiny was not unusual. However, the mutiny on Havmanden is well-documented and can be read according to the organization of means of production as well as the brutality that Europe’s elite based their prosperity upon. In his thesis, Mutiny in the Danish Atlantic World, Johan Heinsen makes note that there existed a dissonance within the European colonial project, and this was manifested in a conflict such as the mutiny on Havmanden. There are three established ways to understand and analyze mutiny. Firstly, mutiny can be understood from a sort of neurosensory perspective, where the lack of food, water, and heat results in a reaction, a kind of auto impulse, to accommodate basic needs. Secondly,

seafaring per se is an extremely ritualistic place that follows the narrative of a theatrical act of sorts. If the narrative changes, the crew can there and then, consider themselves entitled to seize control of the ship. Thirdly, as a more materialistic reading, mutiny can be based upon a conflict between those who own and rule and those whose labour is being exploited. In this case, the mutiny is justified as the ship should belong to those whose labour the voyage is based upon. All three ways to gain an understanding of mutiny can be applied to Havmanden.

Heinsen also introduces dissonance as a fourth reading of the mutiny, where a conflict arises between the speaker and the hearer. Shipping environments are places governed by sound, as visibility in open seas is filled with emptiness. When Governor Iversen attempts to calm the crew with speech, the subordinates hear something else. They know that within one year on St. Thomas they will most likely die from hard labour, starvation, and illnesses. Whatever the Governor says, this is what they hear.

The sea and underwater environment is in itself a place where cognitive dissonance becomes visible. Places that have nothing to do with each other are tied together through the expansiveness of sea, and within this translocation, profits arise, although they are values created at the expense of another. The sea is also a dangerous place where people cannot live. It is a site for the imagination and dreams, but also death.

The so-called discovery of the New World appears to also have led to some unconscious psychological convulsions in the explorers, whose symptoms are represented in works such as Atlantica (1677) by Olof Rudebeck the Elder. In his text, which is a work of propaganda on the Swedish Empire, Rudebeck explains the origin of Sweden through the myth of Atlantis. Rudebeck sets out to prove that all the world’s knowledge originates in the utopia Plato refers to as Atlantis which would be identical with Sweden. His historical works were dismissed by his contemporaries from the outset as being far too imaginative, but Rudebeck’s preoccupation with historical chronology can be read through the discovery of a New World. After Columbus disembarks in the New World, in one instance Europe becomes the Old World.

A work such as Atlantica can be understood as a symptom of a dynamic that arises between new and old territories, giving rise to speculation about who is entitled to the New World.

The camera in my hand is based on the underwater camera that photographer and adventurer Jacques -Yves Costeau developed when he popularised and medialised the underwater environment in the 50s and 60s. With his research vessel Calypso, he undertook several journeys and created films that became commercial successes, such as Le Monde du Silence (The Silent World) from 1956. In the film, we follow the work aboard Calypso, which is not only a moving diving platform on an undefined sea but also a floating photo lab for still and moving photography. In one passage, Costeau describes the overall intention with the mission, whilst also studying the graph from an echo sounder which, through electroacoustics, maps the depth of the ocean below the vessel. Costeau explains that an echo often appears, as though there is something very large thousands of metres down that has yet to be explained.

Costeau arranges for cameras to be lowered down into the dark to photograph whatever may be down there, and despite the film being developed on-board, he finds no answers. The void appears to be the driving force.

In another scene, the crew is engaged in following a group of whales. Unfortunately enough, Calypso accidentally collides with a whale calf, which is seriously injured. The crew, who feel obliged to kill the injured animal, bring out with ill-concealed delight, the harpoon cannon and kill the calf. What follows is a particularly strange scene, which swiftly tells us something about the unconsciousness of the crew. A group of sharks is attracted to the dead whale and begins to eat at the dead body. Initially, the crew becomes interested in studying the sharks, but suddenly their curiosity turns into fury. In a rage, they go after the sharks that are quite close to the surface, and with hooks, axes, and sledgehammers kill shark after shark. I wonder what it is in this specific homosocial environment that brings forth such affective actions? The sea, the emptiness, the violence - is it the scientists' critical distance and judgment that enables a verdict over the non-human sharks?

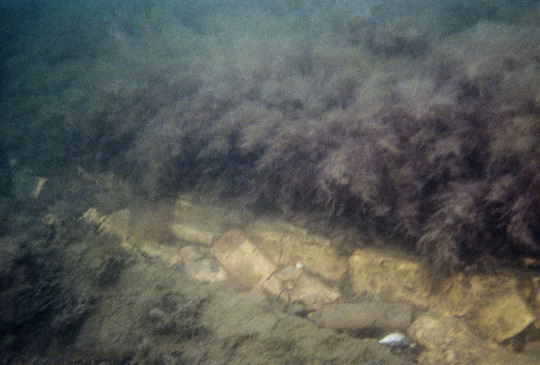

Now I sense the bottom. The pressure on my eardrums increases and I have to equalise by pressing air through my nose into my ears. The ocean floor is smooth with some vegetation. Since my time here is restricted to my ability to conserve the oxygen I have in my body, I have decided to photograph straight ahead and indiscriminately. I simply wind up the film and continuously press down the shutter. The camera has been preset, and I now photograph as much as I can.

Then, suddenly, a structure manifests itself. It is two dark lines that criss-cross over the ocean floor. A straight angle is rarely natural. When I come closer I see what it is: two rectangular piles of square stones are sunk into the sand. It can be nothing other than bricks. This is what remains from Havmanden. For 338 years they have rested at the bottom of the sea whilst the shipwreck rotted away.

The bricks filled two functions on Havmanden. Firstly, as a ballast to stabilise the ship whilst sailing. Secondly, once the frigate had arrived on St. Thomas, they were intended to become buildings from which the colony was to be ruled and administered. For a few seconds, I hover over the objects and view them through the glass of the mask. The mask and camera provide me with a sort of optical privilege that is based on the distance between myself and the stones, and between me and history. At the same time, I cannot stop but feel a sense of closeness, we share the same enclosing substance, the sea.

The stones hardly have any vegetation on them, which surprises me. I have a hard time determining their colour as the light of longer wavelengths, such as red and yellow, cannot probe this depth which blue-green can. Everything turns a cyan-colour yet I am convinced that these are not red bricks but yellow-brown. It is said they have the same origin as the bricks in the house Charlottenburg in Copenhagen, where The Royal Art Academy can be found.

The oxygen in my body is running out and the carbon dioxide induces an intense longing to breathe. I stop myself from the impulse to touch one of the stones, as they are subject to the Antiquities Act. Instead, I turn towards the surface and the sun that breaches through the waves. I kick with my feet, find some momentum, and in an instance I am back in the summer coastal landscape. Yet before I can breathe I have to blow the water of Kattegatt out of my snorkel and mouth.

A few weeks later, when I have immersed the film into developing chemicals and then allowed it to dry, I have the opportunity to, at a distance, view the event through the negatives on my light table. It turns out that I have not managed to capture a single sharp image of the wreck of Havmanden. It appears that I have either not held the camera still enough or managed to set the sharpness. Somewhat downcast in spirit I put the negatives aside before recalling Captain Cousteau’s expedition to photograph ghost echoes in the depths of the sea and I decide to look through the images one more time, as if perhaps, there might be something there. I seem to have taken some pictures straight out which, when I scan the images, appears to be nothing more than a tone of blue-green. However, I bring up the contrast and I can then see a refraction running vertically across the image. It is sunlight refracted in the water surface and hits what is called backscatter in the water, and therefore it becomes prominent. The last image from the dive is taken at the same time as I turn away from the bottom and swim upwards, it is photographed straight towards the sun from the wreck. The film on the light table is in itself a surface that lets through light and through it another membrane appears. It is the boundary between air and water that, through the forms of the waves, creates a series of lenses that generate light beams. Just as the film mediates between that at which a given moment has taken place, with certain specific requirements, the sea surface appears to create a boundary between different states. This dividing line can be likened to photography’s making of disparities, which appears to elicit both distress and possibilities, ultimately introducing a crisis. I recall one final scene from The Silent World where Cousteau says the imperative sentence “Sometimes a marine biologist must use dynamite on a coral reef”, meaning that in order to scientifically count how many fish there are in a coral reef he must explode dynamite to kill them all – taking photographs is not accurate enough. The explosion in this scene resembles a miniature version of the French nuclear test from the Mururora atoll in the Pacific during the 1960s. Cousteau acknowledges what he is doing as an act of vandalism, but also states that this needs to be done in the name of science. This type of reasoning can be understood through theorist Ariella Azoulay´s text Unlearning decisive moments of Photography, where she links the colonial ideology of the imperial right to take photographs to the imperial right to destroy existing worlds and the right to manufacture a new world.

As it turns out the realm of the underwater is not silent at all, but rather a world of dissonance.

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Imaginary Geometry

Haninge Konsthall 2021, collaboration with geographer Johanna Adolfsson.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Public commission for Stockholm Konst, Rågsved centrum 2021. Poster with sound work on Spotify

https://open.spotify.com/episode/4I2oQBfjjUb5sFwGwRUygm

0 notes

Photo

Field Guide to Föralinjen. Collaboration With Axel Andersson historian, Johanna Adolfsson and Maja Lagerqvist geographers

0 notes

Photo

Varaktigt övergiven (permanently abandoned)

Collaboration with Emanuel Cerderqvist for the exhibition Field Work at Kalmar artmuseum.

Photographic montage, infra red, ultreviolett spectrum. Observations along the Föralinjen (defence line from 1940) at Öland Sweden.

0 notes

Photo

the International Museum of Resistance 1978 – 2020 Södertälje Konsthall

Sound from Nobelprize award ceremony in Stockholm 1976, protest against economist Milton Friedman

2o second tape loop

two photograps 100/120 cm.

0 notes

Photo

Okulärbesiktning 2017 – 2019 Photography 400 x 300 cm

Gothenburg International Biennial of Contemporary Art Andersson’s photomontage Ockulärbesiktning (visual inspection) deals with the Bohuslän region’s plethora of Bronze Age petroglyphs and how these have been interpreted and reinterpreted throughout history. With the archives of the Tanum Rock Carving Museum and his own fieldwork as the point of departure, Andersson gives form to the shifting interpretations of the petroglyphs, from the Bohuslän priests of the 1850s and the idea of the Swedish nation state to the German pseudo-researchers of the 1930s and our own time’s academic archeology. Because the carvings come from a time before written history, they are hard to interpret. Archetypes such as boats and animals are recognizable, but what their meaning was in their original context is unclear. The stories hidden within the carvings mean that each attempt to interpret them is highly colored by its own time and thereby reveals something about itself. Today the prevailing opinion is that the petroglyphs are related to long-distance trade.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Publication 2018

http://www.mountanalogue.org/

Marabouparken

0 notes

Photo

Luleå biennial 2018

Snow, Darkness and Cold is a study of the Udtja region in Norrbotten through a four-channel slide show. In a photographic montage, the moss, lichen and flora of the forest overlap with pictures from anthropological studies, and traces of the military activities that have taken place in the area since the beginning of the Cold War. The work takes as its starting point the zoologist and photographer Carl Fries’ contribution to the yearbook of the Swedish Tourist Association from 1924. Through text and photography, Fries describes a walk through Udtja, located in Sápmi between Jokkmokk and Arjeplog. As part of Sweden’s popular education project, he portrays the nature, people and wildlife that he encounters in the unspoiled landscape. Through the lens of the camera, we follow Andersson as he traces the ideological transformations of the landscape: In 1958 the Defence Agency built a massive Robot Testing Ground (RFN) in the area, the same size as all of Blekinge county (some 3000 sq km). RFN was the main testing facility in Sweden, established with the ambition to begin a nuclear programme. As the infrastructure expanded, more jobs were created, and the town of Vidsel as well as an airport was built. From there, the people in Udtja’s Sami villages were flown out as the military needed space for their training. In 2004, the state produced a report on how international military testing and training on Swedish territory ought to be developed for the future. It was concluded that “the combination of the large and sparsely populated area, the climate and the existing military infrastructure creates almost unique conditions for military testing and training activity.” Since then, business in Udtja has entirely focused on foreign clients, the weapon industry, and the military. It has become the centre of the collaboration between Swedish Defence and NATO.

vimeo

0 notes

Photo

Galleri Riis Stockholm

OBSLÖSA

10 Photographs from a military practice field on Gotland Sweden. The area was used during the cold war and was abandoned during the 1990s. Due to Swedens involvement in the conflict in Afghanistan and because the terrain resembled the Afghan milieu the area was again used for military purposes in early 2000.

0 notes

Photo

Galleri Riis Stockholm

When members of the Swedish Parliament want to rest their eyes on something whilst working in the assembly hall, they can do so by admiring Elisabet Hasselberg Olsson's (1932-2012) large tapestry Memory of a Landscape from 1983. The work consists of 200 shades of dyed grey flax, collected from all parts of Sweden. It depicts a landscape observed from a height, and if we follow the imagined gaze of the viewer to the east, it corresponds with the actual Stockholm archipelago. A haze blurring the geography strengthens the landscape´s lack of human presence. That a landscape is depicted makes sense. Landscapes reflect the industrial development where the difference between city and country, and my country and your country have been decisive. The optics with which we regard a landscape is marked by boundaries. It may not be visible inside the Parliament, but well outside.

The exhibition takes the locality of Galleri Riis Stockholm as its starting point. The activities in the Art Academy building is completely encircled by government departments and offices, and it lies opposite the Swedish Parliament. Arts possible function in a geography consisting of Sweden's administrative centre is the subject for the exhibition, and with this gaze the works can be seen as a postscript to Memory of a Landscape. The artworks in the exhibition deal in different ways with how experiences of landscapes and geographies are created. It can be about the way we want to and are allowed to move in a landscape, how ownership is constituted by image, strategies to create new rooms, ideas about ourselves in a historical landscape as well as linguistic boundaries.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Inauguration of a monument.

100 photographs from Titos personal archive taken 05-09-1971. The Yugoslav president visits the Sutjeska monument, commemorating the partisan battle of 1943. Later that day he visits the movie set of the film Sutjeska where the actor Richard Burton plays Tito as the commander of the Partisans.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

In 1935 and 1936 Belgian historian Herman Wirth led a German expedition to the northern parts of the Swedish shire Bohuslän. The target for the journey was to document the bronze age rock art which can be found in great numbers in this area. Large plaster casts was made and sent back to Berlin. After the war the casts were forgotten but was rediscoverd in 2013.

Exhibition at Gerlesborgsskolan 2016. 10 Photographs

0 notes

Video

vimeo

Participant Observers

Exhibition and research project at Marabouparken Konsthall 2015

Slide show.

Images: from the anti nuclear arms march 1961 (Sundbybergs Museum)

Sound: reading from the rapport of two millitary psychologist who posed as “participant observers” in the march.

English translation:

Excerpts from “Detailed accounts of contacts made during the march made by…”

An elderly participant in the march went around selling badges worn by the protesters. The symbol on the badge is the runic character for death and it was visible on most posters and banderolles. I bought a badge and pinned it to my coat and felt like a member of the group and then mingled with the people on the grass lawn. There I made my first contact, but of an unexpected kind, with a couple of Danes who kindly pointed out to me that my badge was upside-down.

A woman (author) read a poem in regular ”Beat nick” style about heavens and punishments and far away. Part of the spectacle was a group of young musicians who played and the marching bohemians were making improvised dance movements, much to the discontent of the organisers.

After the next break I found a new position in the march and made contact with two ladies in their fifties and after chatting a while they also turned out to be active communists. They were marching for the party and read Ny Dag (??) and were feeling pretty satisfied with themselves for marching such a distance for a good cause.

Outside FOA a man walked along the line of marchers and told the participants: ”here it is”. Most participants reacted with an ”oh yeah” only a small Danish woman ”a professional demonstrator” asked if we shouldn’t stop and demonstrate but her suggestion went unheard.

On the Ursvik football field there was music and some curious people and the organisers. The bohemians instantly started to dance, again to the discontent of the organisers.

The participants spread out and the speakers conveyed their heart wrenching depictions.

The marchers came, sat down and ate from their pick-nicks, brought or bought, in all friendliness and in wonderful weather (during the evening I overheard a bitter little speech in a group of organisers about the sandwich- eating mentality of the march participants.

…the big group of Danes, Norwegians and Swedish odd balls, a group of Swedish school youth, who sang popular songs with guitar and generally entertained themselves to the best of their ability and a group of 5-6 youths, that had me associating to rockabillies.

In Alvik I discovered that one of the Danes that generally looked as dishevelled as the rest, held a high position within the hierarchy of the group of organisers.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Participant Observers

Exhibition at Marabouparken konsthall 2015 on the Swedish defense sience facilities (closed 2005).

A wooded area the size of a small nature reserve south of Järvafältet in northern Sundbyberg, Ursvik, was until recently the location of the Swedish Defence Research Agency (FOI). From 1930 onwards, a branch line of the Northern Main Line carried shipments of ammunition into a large rock shelter. The area contained shooting ranges, administration offices and depots, and, most importantly, high level research was conducted there. The research included everything from the development of Swedish nuclear weapons to medical research into surgical methods of treating crush injuries. The activities were top secret and what really went on behind the fence remains shrouded in mystery. In the early 1960s, public support for the Swedish nuclear programme waned and in 1961 the first protest march against the atomic bomb in Sweden went to Ursvik. Pictures from the march are preserved in the Museum of Sundbyberg. The Swedish Defence premises in Ursvik also housed something else, an art collection, which was primarily acquired by the Public Art Agency Sweden. An art collection at a secret location – what was it doing there?”

0 notes