Text

Wine and writing in dark times

SHOREDITCH looked almost handsome in the late-winter sunlight filtering through the big windows of the Ace Hotel's top floor. As I chatted to Jim Clendenen and tasted his crystalline Au Bon Climat wines, the COVID-19 epidemic was a persistent cloud at the back of mind, though not much larger than those scattered across the sky outside. Perhaps others felt the same, with the Essential California tasting less rammed than I'd expected.

That was last Thursday. Today it seems more like a month ago.

In those past seven days the pandemic has galloped through our collective consciousness. Daily, its progress shocks us, every few hours grimly re-arranging our expectations. I have worked for 25 years in communications and journalism, 11 of them in Fleet St, through the news-cycle insanity of wars, elections and terror attacks. I have never seen anything remotely resembling the dizzying speed and spiralling fear of this event.

And writing now, in virtual lockdown at home, about last week's Californian tasting?

I had wanted to write about Alex Krause's astonishing old-vine Birichino wines, his graceful Besson vineyard grenache and zinfandel; about a lovely Brand & Family La Marea Spur Ranch Grenache, and Pax's cool-climate Mendocino County syrah; of the idiosyncratic fiano and other Italians grown in Paso Robles by Giornata, and engaging Spanish varietals from Ferdinand Wines; and lovely wines from old favourites like Stag's Leap and Au Bon Climat.

Yet to do so now seems at best off-key. And at worst? Bertolt Brecht wrote in his transfixing 1938 poem, To those born later (An die Nachgeborenen):

“What kind of times are they, when

To talk about trees is almost a crime

Because it implies silence about so many horrors?

When the man over there calmly crossing the street

Is already perhaps beyond the reach of his friends

Who are in need?”

“Truly I live in dark times!”, Brecht begins his poem, writing in a Europe about to slide into the charnel house of World War II. In Britain this evening I believe we are on the brink of almost certainly tens and perhaps hundreds of thousands of deaths (there’s no good reason to believe we’ll fare any better than Italy); the likely collapse of large parts of the NHS; and catastrophic economic damage. Dark times – though not the darkest. So writing about wine does not seem a crime. Just, well, a bit silly.

I count myself fortunate in not depending on wine writing to put food on the table: for me it is nowadays just a hobby. Still, it is hard to concentrate – on anything – with the constant presence in our hands (“doom surfing”) of the BBC news site and Twitter. And it’s very hard to keep any writing on wine and food in perspective.

Yet at one level we have to keep writing simply because that is what we do, and because normality is so desperately important in such abnormal times. Even if you don’t need to write to live, any writer still has to write to stay sane.

More important, wine goes beyond such routine. Whether wine is our livelihood or not, for all of us it is fundamental to our enjoyment of life and social living. Wine is joyously present in so many of my memories, whether I can remember the particular bottle or not: the Hermitage I somehow bought for my father’s birthday when I was 17; the Chateau Musars I shared with Serge Hochar as the machine guns rattled in East Beirut; the fabulous burgundies drunk under the stars one July on my first visit as a critic to Beaune.

It is the modest Tuscan red I sip next to my laughing three-year-old daughter in a holiday picture 15 years ago and also the glass of Vacqueyras I share with her as a beautiful, super-articulate young woman at the dinner I cooked this evening (pic above); the drunken night when dear American grad school friends presented me with my first Oxford Companion to Wine; the glasses of Crémant de Bourgogne my wife and I raise in our wedding photos.

Wine is life. It’s a daily celebration of the sensual and of our social being: a pleasure that exists to be shared. It’s one of the threads that hold our humanity together. So yes, even at this moment we continue to celebrate it. Because it is one of the things that, shared, will surely help us through these dark times.

19 March 2020

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

My big fat Greek fusion dinner

It remains a mystery why London’s Greek restaurants are so rubbish. Ok, not rubbish, just... unadventurous. Regular readers of this blog will know it’s a question I’ve asked of Greece’s own restaurants too.

This is not to deny that I have a slavish devotion to taramasalata, gyros and pork souvlaki (indeed I am salivating as I type these words) – and for such traditional fare, it’s hard to beat joints like Mornington Crescent’s Yamas. Meanwhile the proliferation amidst the street food explosion of souvlaki stalls like PopBrixton’s excellent Souvlaki Street has brought joy to my life.

It’s just that Greek food as delivered in Athens’s more on-trend eateries can be so much more inventive – and it could be thus in London.

We have a fairly sizeable community of educated, food-conscious Greeks (OK, so there isn’t really another kind of Greek.) Perhaps even important, the influence here of Yotam Ottolenghi seems to wax ever stronger in popularising eastern-Mediterranean fusion cuisine. There’s now a Sainsbury’s own-brand za’atar, for God’s sake. And there’s a thrillingly eclectic approach to Greek food on show at restaurants like the “pan-Balkan” Peckham Bazaar and it’s new-ish sister restaurant, the low-key-but-brilliant Dulwich Lyceum.

But to see such innovation from Greek Londoners (Peckham Bazaar’s John Gionleka is Albanian) is rare. There’s the very decent Mazi in Notting Hill, with its deconstructed classics. But Theodore Kyriakou’s fine Greek Larder in King’s Cross has closed, while his Real Greek has long since been sold on, subsiding into chain mediocrity.

Enter Ampéli, a new venture from delightful Athenian news-photographer-turned-restaurateur Jenny Pagoni. Ampéli freely borrows from across the eastern Mediterranean and indeed even further around its shores – not surprising, given that Head Chef Oren Goldfeld is an Ottolenghi veteran, ex-Nopi. And the result is very successful.

The menu is focussed on snacks and “social plates” – mezze for sharing – though there are larger plates and desserts too. We stuck to the shared plates, starting with whipped feta with pistachio, Aleppo pepper – a sophisticated take on the classic htipiti dip. The Eastern Mediterranean fusion is clear on dishes such as the delectable pan-fried lamb sweetbreads with Jerusalem spice mix, almond sauce, pickles, or a raw salad of market vegetables, aromatic herbs, Tsalafouti cheese, preserved lemon, za’atar.

And there are other dishes that mix influences even more freely: spiced potato burik with brown shrimp, runny egg yolk, harissa mayo (irresistible), salt cod croquettes, samphire and yoghurt tartar (very good) and home-cured tuna “Pastirma” (aka Andalucia’s mojama), fava purée and capers on toasted sourdough. Plus are a handful of more traditional Greek offerings are tucked away on the menu, such as baked gigantes beans with smoked Metsovone cheese.

Just as important, Ampéli’s wine list is impressive – indeed probably now the most extensive Greek list in London, though not such a surprise given the restaurant’s name (ampeli/ αμπέλι means vineyard). Curated by Greek MW Yiannis Karakasis, it includes a long list by the glass. There are plenty of unusual regions and producers here: I particularly enyoyed Chloe Chatzivaritis’s “Mus” 2018, Goumenissa, full of classic xinomavro fragrance and elegance, and Rouvalis Winery’s “Tsiggelo” 2017, PGI Slopes of Aigialeia, a rare fully dry mavrodaphne. I have to admit I was less impressed with the “new age retsina”. And there are better-established favourites here too from Sigalas, Thymiopoulos, Biblia Chora and Gerovassiliou.

Ampéli is a must-try for any devotee of Greek wine and food. Just don’t try asking for moussaka and chips…

Ampéli, 18 Charlotte St, London W1 020 33555370 www.ampeli.london

14 February 2020

1 note

·

View note

Text

Yapp Bros and how I got serious about wine

AT the recent London tasting by French regional specialist Yapp Brothers, I had the feeling of running into old friends as I tasted long-admired wines. But none more so than the Bandols of Domaine Bunan - because they were pretty much where I started in wine.

I had liked wine since my late teens. But it wasn’t until a visit to Sonoma’s Russian River in 1992, at the age of 27, that for the first time I tasted different cuvées and vintages side by side. A light went on.

Five years, a transatlantic move and a big career change later, I was pondering what to serve my wine-loving father at a meal I was preparing for his 60th birthday. I wanted to cook him, my mother and girlfriend my then-signature dish of seared tuna (it was the 1990s) with garlic and piperade.

But what to pair with this muscular fish dish, its fat cut by the acid of the piperade’s tomatoes and a hefty slug of garlic? The advice of my mother-in-law’s partner, David, was unhesitating: Domaine Bunan Bandol Blanc.

It's a fairly obscure wine, with only 15,000 bottles a year made - but I trusted his advice. David Restrick (1939-2004) was a force of nature: an opinionated, hyperactive, witty and regularly infuriating bon viveur. On paper we didn’t have much in common: he was an ex-Scottish and Newcastle wunderkind-turned-management consultant, a Tory and part-time gentleman farmer. I was a Labour Party apparatchik and former Marxist historian.

But we shared a robust pragmatism (he would have been outraged by the economic stupidity of Brexit) and an acerbic sense of humour. And we were brought together by our ribbing of my mother-in-law - as well our love of wine. David knew vastly more than me, generously sharing both his knowledge and his wine cellar.

So I wanted to follow his recommendation on the Bunan Bandol: but it was sold only by Yapp, and by the case. It is easy for wine people to forget just how extravagant and scary it feels the first time you buy 12 bottles of wine AT ONCE. It certainly was for me in Spring 1997: I was poorly paid and didn’t have anywhere to store wine in the grotty north London flat I shared with a friend. Still, I gritted my teeth and ordered a mixed case of Bunan wines.

The wine and meal were a great success. And as my life got more grown-up over the next couple of couple of years (I married the girlfriend and we bought our first flat), I realised I'd also crossed a rubicon with that first case of wine. At David’s urging, I joined the Wine Society. I pored over Jancis Robinson and Hugh Johnson's World Atlas of Wine. I became a bit obsessed.

Which is why I grinned as I tasted Bunan's Mas de la Rouvière rouge and rosé the other week. Wine effortlessly bridges time and distance like that. It's all the more pleasing when it has such significant associations with the past. But in the present, as ever Yapp's list has plenty to like.

Domaine Bunan Mas de la Rouvière rosé 2018, Bandol - still one of my favourite rosés anywhere: a nice weight, full yet fresh, beautifully balanced (£20.50.) The rouge 2015 (£21.25) is muscular, dense, peppery - a lovely wine but I'd leave it another five years.

Domaine Ferrer-Ribière "L'Empreinte du Temps" 2017, IGP Côtes Catalanes - from very old grenache blanc vines (hence the cuvée's name), this is rich, intense, complex, in a slightly oxidative style. Very unusual, utterly individual, made from organic grapes by a Roussillon winemaker who has been one of my favourites since I tasted there in 2010 (£14.95.)

Domaine J-L Chave Sélection Blanche 2015, Hermitage - made from 100 per cent marsanne, mostly from the tiny "Maison Blanche" lieu-dit high on the hill of Hermitage, this is less expensive than Chave's top cuvée as it includes some bought-in grapes. But this is still an extremely serious wine: full, dense, complex, long (£39.95.)

Antoine Graillot and Raúl Pérez "Encinas" 2016, Bierzo - Yapp's Spanish range is small and here has a link with the company's Rhône-focussed origins, in the shape of Antoine Graillot, youngest son of Crozes-Hermitage star Alain. This is an irresistible Bierzo: vibrant, gamy, almost animal, brimming with sweet, pure, crunchy mencia fruit and a lively acidity (£22.)

Pascal Frères Crozes-Hermitage 2016 - textbook Crozes, and a classic Northern Rhône syrah: dark, full of brambly fruit, its weight well balanced with good acidity and chewy tannins (£16.25.)

Domaine Filliatreau Saumur Champigny Veilles Vignes 2005 - Filliatreau remain my favourite producer in this, my favourite Loire red appellation, just east of Saumur along the river. This cuvée comes from 80 year-old cabernet franc vines. The age is showing in the colour of this 2005, along with leathery and earthy notes; still lots of dark fruit, though, and surprisingly firm tannins for its age. Complex and rare (£34.80.)

28 September 2019

Pictured above: Domaine Bunan’s Château de la Rouviére vineyard (pic from Domaine Bunan website)

0 notes

Photo

Something I learned today* One of the things I love about wine is the way it constantly surprises you. You regularly realise how much you still don’t know (or at least I do): new places, new grapes, new twists on wines you thought you knew well. But for that, you need good, adventurous wine merchants prepared to seek out the new: you’re never going to find many surprises in the supermarket. And I was reminded of this at today’s tasting from the ever-brilliant The Bunch collective of independent wine merchants. Here, in no particular order, are some of the things I learnt today in the course of an hour and a half’s tasting (interspersed with long and anguished handwringing with Fiona Beckett, Anthony Rose, Olly Smith and others about the current state of our Brexiteer-hijacked nation). * Hüsker Dü, pictured above - 1984, from Zen Arcade: see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rktLCGpQ3RA.

You can make Rioja taste like Beaujolais – Artuke Rioja 2018 (Lea and Sandeman, £11.95): I exaggerate somewhat but I honestly would not have recognised this as a Rioja, even though it’s 95 per cent tempranillo (the rest is viura – I’ll admit that I didn’t know you could use white grapes in Rioja, though perhaps I should have.) Carbonic maceration gives this wine a uniquely juicy and, well, Beaujolais-y tang. Not sure it would be my choice but it was arresting. And to be honest I could have put the contents of the entire brilliant Lea and Sandeman table in here too… You can make almost-rosé champagne that’s not rosé – Champagne Gatinois Brut Tradition NV, Grand Cru Ay (Hayes, Hanson and Clark, £34.45): this champagne is not listed as a rose, and its very delicate, slightly-pink colour can’t be the product of more than a couple of hours’ skin contact at most. Still, the 90 per cent pinot noir fruit shines through deliciously – expressive and long. Very unusual. Picpoul can be quite nice – (Adnams Picpoul de Pinet 2018, £7.49): It’s not the greatest-ever vinous revelation but I for one have got pretty tired of the ubiquity on even pub wine lists of flabby, blah Picpoul de Pinet: better than pub pinot grigio or a kick in the groin, slightly less enjoyable than a half of Stella. So it was a pleasure to taste this Picpoul, made for Adnams by Jeanjean. OK, so Jeanjean are now part of the giant AdVini group, reportedly France’s fourth-largest wine company, but one with its roots still firmly in its home patch of the Languedoc. And this is very decent at the price: clean and well-balanced with a little bit of breadth. There’s another Chablis taste-alike north of the Côte d’Or – Sorin Coquard Bourgogne Blanc 2016, Côte d’Auxerre (Private Cellar, £14.75): as something of a French geography anorak, I’m embarrassed to admit that I had until now missed the Cote d’Auxerre appellation (the generic AOC for the area around Irancy and St Bris, south-west of Chablis on the other side of the Autoroute du Soleil.) Pure and taut chardonnay with a quite Chablis-like stoney, mineral quality. There is a talented French winemaker called Gaylord – Domaine Gaylord Machon “Cuvée Lhony” 2015, Crozes-Hermitage (Lea and Sandeman, £25.95): one might suppose that most people with parents mad or cruel enough to call them “Gaylord” would themselves learn the lesson and name their boys, say, John (or Jean). Not Gaylord Machon, whose sons rejoice in the names Lhony and Ghany – after which he has named his two cuvées of Crozes-Hermitage. And fair play to him, this one is about as serious as Crozes gets: gorgeous fresh, brambly fruit with the added depth and structure of a strong vintage. Top notch. There’s a decent Austrian grape called Neuberger – Feiler-Artinger Neuberger 2017, Burgenland (Tanners, £22.50): writing this, it’s almost inevitable that tonight I will run into crowds of office workers drunk on this Austrian grape after over-indulging at one of the popular “Neuburger ‘n’ a Nurnburger” wine-and-sausage promos in local pubs. Still, I hadn’t come across it before this tasting. Apparently a roter veltliner/sylvaner cross, as some drunken smartass will doubtless tell me tonight before getting in the next round of neubergers. Quite full, fruity, well-balanced, expressive: for this kind of money to be honest I’d prefer a top-end grüner veltiner – but this is intriguing. You can make syrah in Morocco that tastes like the northern Rhône – Domaine des Ouled, Thaleb Syrah du Maroc “Tandem” 2017 (Yapp, £16.25): northern Rhône superstar Alain Graillot and partner Jacques Poulain make this syrah 30km north of Casablanca, Morocco. I guess the combination of altitude, Atlantic breezes, Crozes-Hermitage clones and a Rhône winemaker account for the fact that, although it’s made the best part of 1200km-plus south of Tain L’Hermitage, it tastes very, well, Crozes-like in its freshness and acidity, albeit with a bit more depth and fruit. Very good. Vaccarèse and Terret Noir are actual Rhône grapes – Gourt de Mautens 2015, IGP Vaucluse (Corney and Barrow, £54.75): I suppose I should know by the heart the grapes permitted in the Rasteau AOC (no Googling now) but while the grenache noir dominant in this is inter-planted with syrah, mourvèdre and cinsault (predictable), is Châteauneuf-du-Pape curiosity counoise allowed? Every wine critic remembers, with a mixture sympathy and schadenfreude, our colleague Oz Clarke’s televised failure to identify this and most of the other eight permitted Châteauneuf red grapes in a blind tasting – so I’ll admit now that I had forgotten the very existence of the vaccarèse and terret noir grapes in this group. Whether in their proportion or their mere unauthorised presence, they dictate that this Rasteau is actually labelled an IGP Vaucluse. And our government fancy their chances against French bureaucrats? Hilarious. Anyway, this is fantastically luscious and long, if expensive. Hüsker Dü’s legendary frontman Bob Mould plays The Garage, Islington on Sunday 29 September 19 September 2019

1 note

·

View note

Text

When red goes with (fried) fish

ONE of the more memorable wine tastings I’ve attended in recent years took place in a fish and chip shop.

To be exact, it was at my local chippie, Herne Hill’s celebrated Olley’s, and its purpose was to match a range of (mostly white) English wines against owner Harry Niazi’s many (mostly deep-fried) fish goodies. Yet as Harry (pictured above) points out, around 20 per cent of the wine that customers in his restaurant order is red, we must assume largely on the fine principle that the best wine match is whatever you damn well feel like drinking. So what should they be choosing?

My bible on such matters, my friend Victoria Moore’s Wine Dine Dictionary, doesn’t offer a lot of advice on red wine and fried fish. The PR behind the Olley’s English tasting, the urbane Rupert Ponsonby of RnR Teamwork, agreed with Harry that the only way to be sure was to taste and match once again.

I naively assumed that this exercise would be quicker than the previous marathon (“Yeah, that was the one where we all got pissed, wasn’t it?” conceded Harry as I shook his hand.) Having whipped through the 12 reds to be tasted, it quickly became clear that this was a fond hope as the food started to arrive: the prawn cocktails were just the first of ten dishes.

And the results? I assumed that reds with strong tannins would overwhelm white fish – and clash with batter – while juicier ones with higher acidity would work better. That’s certainly true with oilier fish such as salmon and tuna, with which I normally prefer something like a grenache. This tasting broadly bore that out – especially with the starter dishes (prawn cocktail, battered and unbuttered whitebait, grilled mackerel, smoked haddock fishcakes, king prawns in a white wine sauce with chilli).

What surprised me was how well these wines coped with the batter on all five main-dish fishes here (haddock, cod, hake, sea trout and salmon) - though they needed some power to punch through it. These are the wines that worked best, with which fishy highlights.

Robert Oatley G18 Grenache 2018, McLaren Vale – somewhat surprisingly, the best all-rounder of the lot: this fragrant, well-balanced, unoaked Aussie Grenache was especially good with prawns, whitebait and salmon (from £11.95, Cambridge Wine Merchants, Old Bridge Wine Shop, Islington Wines.)

CVNE Crianza 2015, Rioja (£10.75, widely available) – I wouldn’t have guessed that red Rioja would work this well with so many fish – but it did. This supremely reliable Rioja stalwart was good with whitebait, cod and salmon (£10.75, Majestic, Waitrose, Ocado etc.)

Villa Maria Cellar Selection Pinot Noir 2017, Marlborough – pinot noir looked on paper to be an easier match with fish, and this reliable, fruit-driven Kiwi was indeed versatile – especially with whitebait and prawns (£16.40, Sainsbury’s and elsewhere.)

Errazuriz Aconcagua Costa Syrah 2016 – there is oak in this Chilean syrah but its freshness, minerality and bright fruit made it a good match for cod, sea trout and prawns (from £15.75, Ocado, Wine Direct.)

Louis Jadot Beaujolais-Villages Combe aux Jacques 2017 – I’m not generally a Beaujolais fan but this one deserves a special mention for its perfect marriage with Olley’s’ traditional prawn cocktail: if you think Marie Rose sauce defies any wine, think again. It was pretty good with Olley’s amazing home made smoked haddock fishcakes with ginger and coriander too (£11.90 Tesco, Ocado.)

16 September 2019

0 notes

Text

The beautiful south: New Wave South Africa

FOR sheer buzz, it’s hard for me to remember a recent tasting with the excitement of this week’s New Wave South Africa event. It was certainly the first trade tasting I’ve ever had to wait to get into – the venue’s capacity was 320, and 700 people had accepted invites – though I was lucky in queueing only five minutes. By the time I left, a 30-minute line of critics, sommeliers and buyers snaked down Poland St. I’d guess they left feeling it had been worth the wait.

New Wave South Africa was first launched in 2015 to showcase an innovative new generation of Cape winemakers. Launched by Swig, Indigo, Dreyfus Ashby, New Generation Wines and FMV, more importers are now involved in the tasting, though the founders were well represented yesterday (the Dreyfus Ashby and Swig showings were particularly strong.)

The producers tend to be younger and the atmosphere more casual than many trade tastings (most producers were dressed in T-shirts, with the occasional baseball cap). There was a visible camaraderie between them: a number were clearly friends. And they are all producing wines which challenge what were South Africa’s norms a decade ago – in terms of terroir, grapes, technique and above all, quality.

What is most exciting about New Wave South Africa is the snapshot it gives of a wine industry in rapid transition. For anyone like me who has paid less attention to South African wine in recent years, it felt like you’d been caught napping: the transformation was astonishing (not that these producers yet represent the majority there.)

Exciting too was the promise for the future: for instance, a number of the producers I was impressed by currently buy in all their fruit but have planted vines or are trying to acquire their own land. And in areas such as the cool-climate Hemel-en-Aarde valley – source of a number of serious wines on show – apple farms still predominate over vineyards. In a decade’s time, with another ten years of change at this pace, I’d guess it will look very different – and be even more dynamic.

I could only really scratch the surface in the time I had available, but here are a few of my favourites:

Botanica “Arboretum” 2016, Stellenbosch – Ginny Povall makes all of her wines from bought-in fruit, though she has been planting since 2009 and fruit from her own 5ha of vines will hopefully come on stream soon. Arboretum is a Bordeaux blend dominated by 49 per cent cabernet sauvignon: fine-grained tannins, good acidity and well balanced despite its 14.5% alcohol. Her Mary Delany pinot noir 2016 is excellent too, juicy with a savoury edge (Vinosa, The Wine Reserve, from £21.99)

The Foundry grenache blanc 2018, Voor-Paarderberg – The Foundry is the side project of Chris Williams, cellarmaster at Meerlust Estate in Stellenbosch, with friend James Reid. Williams favours Rhône varietals, all grown on granite terroir. For the moment the wines are still vinified at Meerlust. I loved Chris’s fresh, expressive Viognier 2018, Stellenbosch, but this grenache blanc was just about perfect: generous citrus flavours and breadth combined with lovely precision (Berry Bros, £11.67 – 2015.)

Sijnn Touriga Nacional 2012, Malgas – David and Rita Trafford’s estate close to the coast in an isolated part of the central Western Cape has won many plaudits. I was particularly taken by the concentration and, well, very Portuguese character of their touriga nacional, of which they have 2ha planted – big, sweet but with good acidity (N/A/ UK retail; imported by Dreyfus Ashby)

Restless River Main Road and Dignity Cabernet Sauvignon 2016, Upper Hemel-en-Aarde Valley – at 300 metres and 5km from the Atlantic, this higher end of the cool Hemel-en-Aarde Valley is making its name mostly for pinot noir and chardonnay. Anne and Craig Wessels’s cuvées of those grapes are impressive – their Ava Marie Chardonnay 2017 is wonderfully elegant – but I was most taken by this cab. From two vineyards planted across a total of 2.2ha, they make just 1,000 cases of this a year. Pure and fresh with minty fruit notes, well balanced with fine-grained tannins – lovely. Delicious now but this has a long life ahead of it – Craig thinks at least 10 years (M Wine Store, Harvey Nicholls, Hedonism, Handford, from £50.)

Saurwein Chi Riesling 2018, Elgin – Jessica Saurwein buys in all her fruit from cool-climate sites, making stunning wines. Her pinot noirs are superb, especially her Nom Pinot Noir 2018, Elandskloof, vinified in Elgin, but it was her Elgin Riesling, grown just 2km from the ocean, that really blew me away – perfectly poised, a delicate balance of taut acidity and zesty fruit, long. Serious stuff (Lay and Wheeler, Handford, from £24.28.)

Richard Kershaw Clonal Selection Chardonnay 2017, Elgin – British-born winemaker and MW Richard Kershaw has been making wines in this especially cool corner of the Western Cape since 2012. The grapes for this chardonnay are grown at up to 650 metres, 9km from the ocean in Elgin. Supremely elegant and restrained, pure yet well balanced and long, in a very Burgundian style which he insists is mostly down to the terroir. Very classy (Berry Bros, £36.67)

5 September 2019

Pictured above, clockwise from top left: Jessica Saurwein; Craig Wessels of Restless River; Chris Williams of The Foundry; Ginny Povall of Botanica.

0 notes

Text

Albariño and the taste of the Atlantic

THERE can be few local food and wine combinations more perfect than Galician shellfish and Albariño. That, at least, was my feeling as we sat in Santiago de Compostela’s irresistible Abastos market, eating possibly the juiciest, freshest razor clams, octopus and Queen scallops I have ever tasted, and sipping what is today Spain’s best-known white wine.

The Abastos 2.0 bar and restaurant is a serious joint, though, one indication of which being their superb, bright house Albariño, Fiestra, made for them by Attis Bodegas Y Viñedos. So good was it that we decided to pay Attis a visit the next day.

Attis is a producer emblematic of the surge in the fortunes of the Rías Baixas over the past three decades. Galicia’s flagship Denominación de Origen sits mainly on the coastal valleys south and south west of Santiago: Atlantic weather is central to the terroir. The region is so damp that the grapes need to be trained well above the ground to help ward off mildew – in fact on pergolas, usually with grass growing between the vines to help soak up rain. At Attis, most of the pergolas are propped up by pillars made from the terroir’s other key component: granite.

A variety of autochthonous white varietals are grown in the area in this way - especially Loureiro and Treixadura, used mainly in blends - as are local reds such as Caiño Tinto. Indeed Attis has championed these obscure reds, many of the their vines having been torn up in the 1980s and 90s to make way for Albariño. I loved Attis’s highly unusual, fresh, almost animal Xión Cuvée Tinto 2016, a blend of local grapes Souzao, Espadeiro and Pedral.

But Albariño has always been king in Rías Baixas. Established in 1988, the DO has five sub-zones, of which the most important and biggest (by production) is the Val do Salnés (most local place names are nowadays rendered not in Castellano but in Galego, a language that looks likes Portuguese but sounds more like Spanish.)

Attis is in the centre of this zone. The Fariña family’s small wine business was transformed by brothers Robustiano and Baldomero’s decision to set up Attis in 2000, bringing in French winemaker Jean-François Hebrard. Theirs were the most impressive of the Albariños I tasted on this trip. Their range is quite large; these are the ones I enjoyed most of those I tasted:

Attis Genio y Figura 2018 – made from the youngest grapes (some bought in), with elevage in stainless steel, this is a fine and vibrant Albariño: aromatic, complex, fresh, mineral, a slight tang of salt (Barrel and Still, £14.99; Ellis of Richmond have the 2017.)

Attis Albariño Lías Finas 2018 – this cuvée has a little more depth thanks to coming from 40-50 year-old vines, with 25 per cent matured in oak foudres (the rest in stainless.) More subtle than the Genio y Figura, with a wet-wool nose and perhaps more classic Albariño flavour. There’s more breadth and length but it’s still pleasingly fresh (Ministry of Drinks, Simply Wines Direct, £17.99)

Attis “Nana” Albariño 2016 – one of Hebrard’s top cuvées, this is made from grapes from a single, 50 year-old parcel of vines, with the wine all raised in new oak barriques. But while it’s rich and intense, the oak is very well integrated and the wine bright, well balanced and long. A beautiful and serious wine (Simply Wines Direct, £26.99)

From Attis we bowled over the hill into the small town of Cambados, centre of the Rías Baixas wine country and venue that day for its 67th annual Albariño festival. It’s a joyful community event, with upwards of 20 producers offering their wines by the glass to crowds of Galicians picknicking on improbably large tuna empanadas, tortillas and baskets of shellfish. It’s refreshing to see oysters being consumed not as a symbol of luxury or sophistication but as a core ingredient of party time. With a fine range of Albariños, of course: these were my favourites.

Martin Codax “Organistrum” 2015 – Martin Codax is Galicia’s biggest wine cooperative, based in Cambados, and from the outset a standard bearer for the Rías Baixas DO. This is their top cuvée, with 3-4 months in small-medium-sized oak barriques: it has more weight and depth than their simpler wines, though still good acidity and the oak isn’t overdone (imported by Liberty; Wine Direct, Richard Granger, from £19.95)

Viña Almirante, Pionero Maccerato 2018 – from a producer in the far east of the Val do Salnés zone, this is on the brighter and fruitier end of the Albariño flavour spectrum, yet still with very typical varietal character. Precision and focus, fresh yet complex. Lovely. (N/A UK)

Condes de Albarei Pazo Baión 2018 - Pazo Baión is Condes de Albarei’s top cuvée, from a single vineyard of 40 year-old vines. It has six months on its lees, giving it a slightly deeper colour and more depth and complexity; aromatic, mineral, long – very good (Ministry of Drinks, £19.99)

Pictures above from top: Attis’s Ángeles Mosteiro among the bodega’s Albariño vines; me getting into the party mood at the Cambados Albariño festival; volandeiras (Queen scallops), razor clams and Albariño in Santiago market.

7 August 2019

0 notes

Text

Galicia’s green gold: visiting the home of Padrón peppers

AS I rolled into the village of Herbón, I wasn’t quite expecting laughing local maidens carrying brimming baskets of Padrón peppers through the streets. I certainly wasn’t expecting a giant fibreglass pepper on the edge of town of the kind that would be inevitable were this America.

Still, this most-prized spot for the production of the tapas favourite, just outside the small agricultural town of Padrón, seemed remarkably quiet on the Wednesday morning this week when I visited. The village’s only bar, the Casa Dios, was almost deserted - though Padrón peppers were on the succinct tapas menu. It all added to the mystery of how this small area manages to satisfy the insatiable demand of the nation and Europe’s Spanish restaurants for the small, green, sometimes-spicy peppers.

For Padrón peppers are popular not just in their native Galicia but throughout Spain. The only preparation I’ve ever seen is fried and served with sea salt - though in Galicia, at least, they tend to be deep fried rather than pan fried. And delicious they are too - whether at a bar accompanied by a glass of the local Albariño (Galicia is one of the few places in Spain where you still normally get given a small tapa with your drink) or in a larger restaurant portion.

As for the famous rule that one in ten Padrón peppers is fiery, a snacking Russian roulette: from my years of guzzling them, I’d say it’s a far lower proportion than that. As the Galician saying plastered on T-shirts locally has it, “Os pementos de Padrón, uns pican e outros non ("Padrón peppers, some are hot and others not") - an aphorism that goes some way to explaining Gallegos’ reputation in Spain as taciturn and blunt-speaking.

But the peppers all come from near here, now certified as Denominación de Orixe Protexida (the Galego DOP) - an area 20 minutes south west of Santiago de Compostela. Sleepy Herbón and the surrounding area still doesn’t look like an agribusiness landscape: there are more vines than peppers growing by the roadside, and the biggest A Pementeira co-op is made up of 19 mostly smaller, family growers. But polytunnels have given production a big boost over the past few decades: getting on for half of the 34 hectares now planted are under plastic.

They have also permitted the extension of the traditional May-October growing season. Total annual production now stands at an astonishing 1.3 million kilos. And while they’ll never be as cheap and plentiful in the UK as in Santiago de Compostela market or its bars (pictured above), tapas addicts can relax: it doesn’t look like we’ll run out any time soon.

To cook Padrón peppers:

Heat two tbsps of oil oil in a frying pan. When it is really hot - almost smoking - add your peppers (British supermarkets sell them in packets of 130-200g.) Fry for about five minutes, turning occasionally. They should blister a bit. Turn out on to a serving plate and sprinkle generously with sea salt.

● This Saturday, 3 August, Herbón hosts the the 41st annual Festa do Pemento Herbón-Padrón at the village football ground.

2 August 2019

0 notes

Text

How paella became cool

THE execution was perfect. The rice grains sat plump and glossy in the cooking tray, coloured a startling black with squid ink, dotted with morsels of calamari, artichokes and dill, oyster aioli on the side. But I was more struck by this most unconventional of paellas, served amid the bustle of smart new London restaurant Arros QD, knowing the journey both dish and chef had made to get there.

Arros QD is the brainchild of Michelin-starred Spanish chef Quique Dacosta (rice is “arros” in Valencian dialect), and my friend Marcos Fernández, CEO of the Iberica restaurant group. It has been several years in planning. And when I first met Dacosta early last Spring, the paella at hand was very different.

We stood in a makeshift outdoor kitchen by one of the little waterways that snake through the reeds into the Albufera, the shallow lake at the centre of the Valencian rice-growing country. It’s an area with a unique, watery culture – on the shallow boat there, the boatman (pictured above) explained that moorhen was tasty, less meaty than duck – but one dominated by rice.

So paella was in prospect for lunch. Santos Ruiz, director of the body for Denominación de Origen-protected Valencian rice, was wearing the chef’s apron. Dacosta and I shelled garofo beans and sipped wine.

First, Ruiz sautéed the rabbit pieces and some onion (pictured above). Then he sloshed water into the pan with the rabbit bones and head: this would form the stock, a central component of good paella. He took a break to serve us the rabbit liver: “a treat just for the chef and his friends”. When the stock was ready, in went the rice, sprinkled in the shape of a cross. Tomatoes and the beans would follow soon after with the cooked rabbit, and saffron.

Was that it – the ingredients for a true paella? The dish is the subject of more ferocious debates over authenticity than any other European classic – cassoulet included. For purists, the only acceptable main ingredients other than the rice are rabbit and snails; such hardliners reject even seafood paellas, wildly popular in modern Valencia as elsewhere, as heresy.

Dacosta admitted to me that he wouldn’t put wine in his paella because the reaction on social media would be too fierce. And when Jamie Oliver posted a paella recipe online in 2016 that called for chorizo, Spaniards united in vitriolic condemnation of the idea.

But it’s not so simple. The first written-down paella recipes in the eighteenth century were very different from today’s, for example involving eel and cooked for much longer. In truth, its origins are as a country dish that varied according to what was available in a given place and season.

Thus in Ruiz’s home village, beans and artichokes were traditional in winter, rabbit in the summer. Some villages use chicken, others even meatballs. And snails, especially, are more typical of the agriculturally much poorer area further south towards Alicante.

By now our paella was approaching the moment of truth: when the stock has been absorbed and the rice, starting to gelatinate, begins to catch on the bottom of the pan – the prized, crunchy socarrat. To get to this point, even cooking is crucial. Ruiz was adamant that more water cannot be added part-way through, as it would break some grains, while Dacosta carefully checked the quality of this Bomba rice for broken grains before it went in.

Was it ready? When the rice starts to hiss, you’re nearly there – but it’s hard to get right, and if you don’t, for purists, all your hard work will have been for nothing.

Ruiz didn’t blow it: we enjoyed his deeply flavoured paella, complete with socarrat, under the shade nearby – everyone helping themselves out of the large paella (the name of the pan) in the middle of the table.

It was a different scene next morning in Dacosta’s experimental kitchen at his eponymous three-Michelin-star restaurant in Dénia, near Alicante. The night before, I’d enjoyed an astonishing tasting menu there: from flower salad through home-cured fish roes to moray skin with rice, a very Spanish display of creativity. But the paellas that Dacosta was developing for London – our breakfast – were equally innovative.

First a sous chef demonstrated Dacosta’s new secret weapon: a computerised paella pan (pictured above with Dacosta) . A sensor over the pan gave a continuous readout of the stock’s temperature: 18 minutes’ cooking with stock made in advance, 25 minutes in total including sautéeing and resting time. These are not used for all of the paellas in the London restaurant, which boasts a six-metre line of pans bubbling over the wood fires traditional for meat-based paellas. Still, the resulting rice that morning, topped with red mullet and shrimp, was beautiful (pictured above).

And if 25 minutes isn’t quick enough for impatient London diners? Dacosta’s other innovation is a dish made by stopping the rice from cooking after 10 minutes, separating it from the stock, and later finishing it quickly in the oven in a shallow chapa tray. Chapas arrived at the tasting table: first an astonishing green one, the rice cooked in stock coloured by chard, sprinkled with garlic shots and octopus and served with lime (pictured above) .

Then the sous chef demonstrated an all-socarrat paella, one grain of rice thick, peeled off a non-stick pan in one thin pancake. “To get to this level is not easy,” concedes our host. I had a feeling we weren’t in Valencia anymore…

But the self-taught Dacosta is modest about his aims. “The most important thing for me is not whether this is the true paella, but whether you are making paella at home.” He wants to encourage us to make paella as Valencians do, a Sunday lunch celebration where everyone helps out. When you do that, you’re not aiming at perfection: “We’re not perfect in the Mediterranean – and we need to keep on not being perfect”

The food in Arros QD, as in any high-end restaurant, is something very different from any family lunch. But Dacosta has a strong sense of responsibility in presenting Spanish food to the world. “We hope we’re liked, but it’s very important that if someone from here came to the London restaurant, they’d think it was a fair representation.”

Arros QD, 64 Eastcastle St, London W1W 8NQ Tel 020 3883 3525

1 July 2019

0 notes

Text

Sekt appeal

GERMAN Sekt has a bad name – with good reason. Germany churns out around 350 million bottles a year of its sparkling wine, most of it the kind of rubbish to make Lidl prosecco look classy.

The lowest and largest category of sekt doesn’t even have to be made from German grapes (and indeed 90 per cent isn’t completely), while almost all sekt is made with the charmat method. The vast majority is knocked back in Germany, the world’s largest consumer of sparkling wine, guzzling around 400 million bottles of sekt, champagne and the rest every year.

But as elsewhere in what was then a ravaged German wine world, in the early 80s a small group of quality producers began to fight back against the industrial plonk machine. Traditionally produced quality sekt still makes up less than two per cent of total output. However, there is a well established band of producers of Winzersekt (winegrower sekt, effectively the equivalent of grower champagne), producing wine only from their own vineyards and using the traditional (champenoise) method. Quantities are small – not much leaves Germany – but quality high.

I was lucky enough to taste several such producers’ sekts recently chez my friend and guide in all things German, Anne Krebiehl MW. Typically, all but one of these are Rieslings. To qualify as “extra brut” (the second-driest category after “brut nature”), sekt has to contain no more than 6g/litre of residual sugar; brut can contain up to 15g/l, though the two here were well under that. None of these (and the last one here, which I tasted recently on a trip to Mainz) are available in the UK: finding quality sekt here requires determination. But the following is an indication of the quality that’s out there.

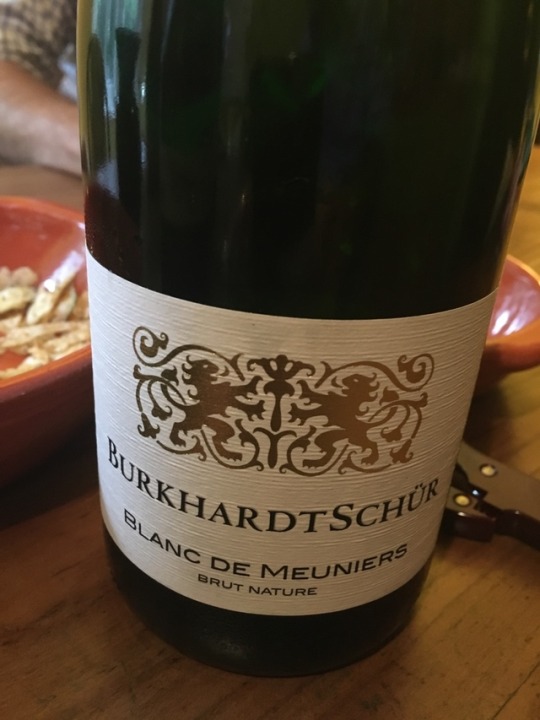

BurkhardtSchür Blanc de Meuniers NV, Franken – This sekt from Sebastian Schür und Laura Burkhardt is a bit unusual both in being from Franken and for being 100 per cent pinot meunier. It’s also a crisp zero dosage, though I wouldn’t have guessed from the fine depth and expressive, floral fruit. (N/A UK; about €22 in Germany)

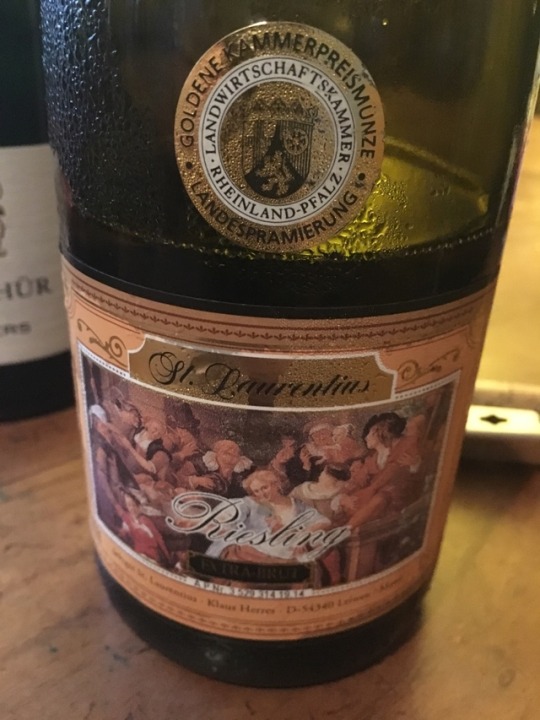

St Laurentius Riesling Sekt Extra Brut 2012, Mosel – attractive golden colour; wonderfully aromatic; crisp and fresh but with admirable breadth and complexity. (N/A UK, €12.50 ex-cellar)

Bamberger Riesling Brut 2012, Nahe – Ute and Heiko Bamberger (pictured above) make serious sekt from their steep vineyards in Meddersheim. The wines have up to three years on the lees before disgorgement, and the bottles are all hand riddled. Pale, fresh, delicate, crisp and precise but well balanced: delicious. This was my favourite of these sekts. (N/A UK; more recent vintages €13.80 ex-cellar)

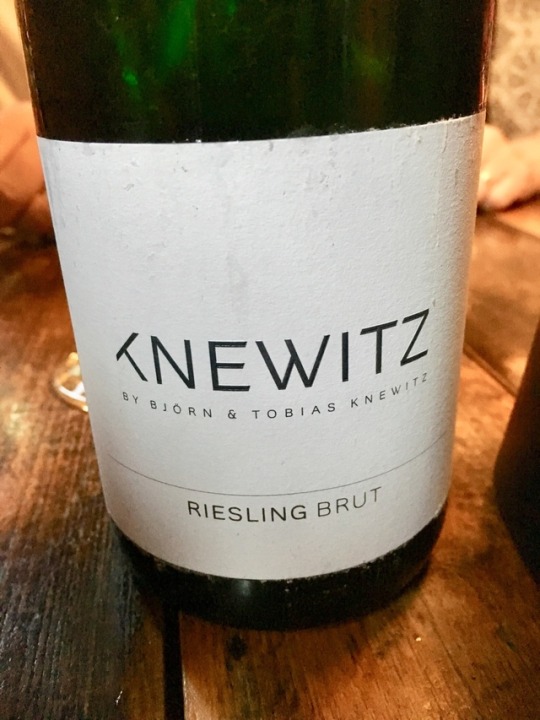

Knewitz Riesling Brut NV, Rheinhessen – light, fresh, citrus fruits and a slight honeyed edge. Very enjoyable. (N/A UK; about €11 in Germany)

Top picture from Weingut Bamberger website

26 June 2019

0 notes

Text

Going to extremes in Champagne

IT was an unusually chilly June morning in Reims last weekend as I set out with my American mate David to introduce him to the joys of champagne tasting. It was my first visit to the region in several years and I had planned a day of contrasts for my old friend.

We started in Reims at Taittinger, at the reassuringly grand end of the producer spectrum, walking through cellars hacked from Gallo-Roman quarries and filled with large-format bottles (pictured above) and Taittinger’s Comtes de Champagne flagship. Then it was to Epernay’s celebrated Avenue de Champagne, to Champagne De Venoge (the posher bit of the BCC group along with Boizel, Chanoine and Lanson.)

We finished the day at Champagne Charlier et Fils in Montigny Sous Chatillon, the Marne valley ravishing in late-afternoon sunshine. Charlier was the first place I ever tasted champagne properly, nearly 20 years ago: I retain a soft spot for this quintessential family récoltant-manipulant operation, big on the locally dominant pinot meunier grape. We sat tasting in the cool of the cellar with Carole Charlier: she is particularly proud of their rosé, made using the traditional saignée method. Their Prestige Rosé NV is indeed hugely enjoyable (N/A UK). Charlier own just 15 hectares, producing around 100,000 bottles a year: about as big a jump as is possible from Taittinger and its four million bottles a year of Brut Réserve NV.

In between these extremes, though, we squeezed a more intriguing contrast of styles – at Alfred Gratien in Epernay and then Henri Giraud in Aÿ.

Like many producers, Alfred Gratien has got in on the area’s burgeoning champagne tourism trade: there’s a slick, newly opened tasting bar as well as tours. Twenty years ago, few producers would let in visitors without an appointment; today many are packing them in at E20-plus a pop.

But not many of them offer wines of Gratien’s supreme finesse, partly thanks to its unusual practice of preventing malolactic fermentation. The crisp and elegant entry-level Brut Nature NV is a good example. But almost all their range is available for tasting: I enjoyed the Cuvée 565 solera-style cuvée: more caramel and richness but still with the house’s trademark elegance and balance (France only – only 4,000 bottles produced).

Better was to come though: Gratien’s Blanc de Blancs 2012, very fine and elegant, gorgeous appley fruit; and most of all the sublime Brut 2006 - real depth on the nose, lovely honeyed notes on palate, rich and complex and yet still so light and crisp (it’s 63 per cent chardonnay) – with years left yet. It’s a seriously impressive champagne. (Wine Society: the 2012 is £39, the 2006 £42.)

Champagne Henri Giraud is different in every way. Aside from the fact that it’s appointment only, it’s about as nonchalantly cool as champagne gets, with a tasting area walled by glass on one side and filled with offbeat objets d’art. But despite its boutique status, since having burst to prominence over the past 20 years, Giraud buy in roughly half their grapes (Gratien, a more conventional négociant-manipulant, buy almost all of theirs.) Most of Giraud’s bought-in grapes go into their entry-level Esprit Nature NV; all of the premium cuvées are made with their own grapes, almost all from Grand Cru plots in Aÿ. And since 2016, Giraud have used no stainless steel: everything is fermented either in barriques or in ceramic “eggs”.

We started with the extraordinary MV13 NV, Aÿ Grand Cru, so called because it is made from a 70 per cent base of 2013 wines, 70 per cent pinot noir and the balance chardonnay (Giraud use no pinot meunier.) It’s a big, rich, powerful wine, with only a slight, fine mousse, all fermented in 80 per cent new oak. But the oak is well integrated and the balance beautiful. It really needs food (various UK independents, from around £150.)

Then we jumped back in the range to the Esprit Nature NV – fresher, 80 per cent pinot noir and negligible oak influence, but still big and rich: a very serious wine for an entry-level offering (around £35 UK). Stepping back up a notch, the extraordinary Hommage à François Hémart NV is somewhere between the two previous wines in weight: big, rich, gloriously intense but perfectly poised, another food wine (70 per cent pinot noir with six months in oak; €50 ex-cellar).)

We finished with Giraud’s Côteaux Champenois rouge 2016, a fascinating oddity, still tight and dense: I think the only still red Champagne wine I’ve ever tasted, and certainly the only one from a Grand Cru. Predictably, just 2,000 bottles are made, the individual numbers engraved on them.

I’ve tasted hundreds of champagnes of contrasting styles. Still, it was refreshing to be reminded anew, in two consecutive tastings, of just how radically different the styles of two top producers can be. Vignerons will of course put most of it down to terroir: at Giraud they’re even convinced of the particular flavour imparted by the soils of the Argonne forest whose oak they use. But inevitably, as a wine involving more stages in its vinification than most, Champagne is correspondingly shaped even more by technique. It adds up to a kaleidoscopic range of possibilities. So, one more day’s exploration - and a whole bunch of new questions.

11 June 2019

0 notes

Photo

Northern exposure: Ontario’s chardonnays

THE annual Canada House showcase of Canadian wines is always one of the more agreeable national tastings. It’s manageable in size, it’s full of ridiculously friendly, helpful Canadians, and the wines are interesting. This year’s, earlier this month, was as enjoyable as ever.

There’s inevitably a geographical gulf down the middle of the offering, between the cool-climate chardonnays and pinot noirs of Ontario and the more powerful wines of British Columbia. This year as last, almost half the wines on show were from BC; bar a scattering of producers from Nova Scotia, the rest were almost all from the shores of Lake Ontario. But while I enjoyed many of the pinot noirs from both ends of the country, it was the balance and precision of the eastern chardonnays that really impressed.

That perhaps shouldn’t be surprising: Brits may tend to think of Canada as the frozen North, but all of the Ontario wine country is further south than Beaune – albeit with a very different climate. These are serious chardonnays in their quality and purity. Sadly, like most Canadian wines, they aren’t cheap (or well represented in the UK – most of the following producers and non of these vintages are available here.) But Ontario chardonnays are well worth seeking out.

Here are half a dozen that particularly impressed me. With the exception of Closson Chase, all of the following are from the Niagara peninsula, west of Niagara Falls on the south shore of Lake Ontario.

Hidden Bench Estate, Felseck Vineyard Chardonnay 2016, Beamsville Bench – from a single limestone plot. Despite the warm vintage and 16 months in oak, this very well balanced and complex, with good length. Very attractive.

Closson Chase Vineyards, South Clos Chardonnay 2017 – Closson Chase is in Prince Edward County, on the other (north-eastern) side of Lake Ontario from Niagara. This is bright, clean, well constructed; toasty with a clear but restrained oak influence.

Henry of Pelham Family Estate, Reserve Chardonnay 2017 - clean, stony, nice acidity and citrus flavours from the rainier 2017 vintage.

Leaning Post Wines, Senchuk Vineyard Chardonnay 2017 – aromatic and mineral: I love the depth, complexity and length of this wine. And astonishingly, it’s only 12.5 per cent alcohol.

Tawse Winery, Quarry Road Chardonnay 2014 – a single-vineyard cuvée from limestone soil, biodynamic cultivation, and a cool, wet vintage: this is taut, pure and very elegant. Serious Burgundian-style chardonnay.

Westcott Vineyards, Estate Chardonnay 2017 – forward fruit, rich and buttery but with attractive balancing freshness. From the Vinemount Ridge VQA (Vintners Quality Alliance – the appellation system for Ontario wines.)

Note: Norman Hardie Winery

: at last year’s tasting, the chardonnays from Norman Hardie, then one of Canada’s most respected winemakers, were some of the most impressive on show. But he has since been hit by local reverberations of the #metoo sexual harassment scandals. Last June the Toronto Globe and Mail published a devastating exposé based on dozens of women’s sickening testimony of Hardie’s unwanted sexual advances, groping and other forms of sexual harassment. Hardie’s wines were until then stocked by many of Canada’s starriest restaurants; they have since dropped by the likes of David McMillan and Fred Morin, his former friends and owners of Toronto’s celebrated Joe Beef restaurant. Should critics boycott them too? They’re still serious wines. But given the strength of feeling in Canada – when the Liquor Control Board of Ontario dropped its temporary suspension of Hardie’s wines last December, there were bitter protests – I decided not to write about them.

Picture: One of Hidden Bench‘s vineyards (picture from the company’s website)

30 May 2019

0 notes

Text

Local heroes: Colli Bolognesi and Italy’s wine patchwork

ONE of Italy’s joys - but a source of confusion too, for wine lovers - is its extreme localism. Just as in food, where a certain shape of pasta will be differently named within a small region, and where locals will fiercely defend the superiority of their village’s sausage compared to the very similar one made 10km down the road, so in wine.

Thus I found myself at a London Wine Fair-week dinner last night organised by the consorzio of the Colli Bolognesi. They’re very proud of the uniqueness of their Denominazione di Origine Controllata Colli Bolognesi wines, even more so of the local grape whose wines enjoy theoretically more exalted DOCG status. Anyone want to name that grape? No Googling now...

Yeah, me neither. It’s Pignoletto, aka Grechetto Gentile, aka (locally) Alionzina. In other words, the local face, from the hills south of Bologna, of Italy’s huge range of indigenous grapes and their many alternate names. Multiply such pockets through the voices of local farmers across the whole country and you get Italy’s 408 different DOC, DOCG and DOP designations (never mind the rest).

It’s a bewildering, defiantly heterogeneous list even to most Italians: I wouldn’t bother trying the Pignoletto quiz on a Ligurian, much less a Calabrian. But each sub-zone is as fiercely proud of its wines – and convinced of their uniqueness – as they are of their sheep’s cheese, or olives, or almond biscuits.

For me, obscure Italian wines are one of the unsung pleasures of the London Wine Fair. Presumably paid for in part by regional funds, small producers with no UK representation (none of the Colli Bolognesi wines mentioned below do)have for years come to the Fair to show off their wines. How much they achieve commercially, I’m not sure: for a start, a fair few don’t speak much English (my Italian is rudimentary yet I’ve had to resort to it on several occasions at the Fair with small producers whose English was even worse.)

The wine is often a mixed bag – though delivered with pride and charm. So it was at the Colli Bolognesi event, with the wines accompanied by regional dishes created by Michelin-starred chef Alberto Bettini of the Trattoria Da Amerigo in Valsamoggia, just west of Bologna. Bettini explained how he had brought large bags of late-season artichokes and other local biodynamic vegetables with him on the plane to cook. Then the President of the Consorzio of Europe’s first DOP garlic, Voghiera, stepped up to explain (in Italian, naturalmente) the unique local white and black bulbs (pictured above) that he had brought with him for Bettini to incorporate into the meal.

And the wine? Pignoletto spumante, the local bubbly, is a crisp, pleasant glass, better than the average Prosecco. But the frizzante versions of the DOCG white left me underwhelmed – though they had a difficult pairing with blanched green asparagus in salty zabaione of parmesan, herbs and flowers (pictured above).

Next an Emilia-Romagnan classic of bolito misto (boiled beef cheek and tongue with chicken) with seasonal vegetables and white Voghiera garlic was paired with two DOC Bologna Biancos. The designation is majority sauvignon blanc. Of these, Manaresi’s Duesettanta 2018 was the most successful, a sauvignon/chardonnay/grechetto gentile blend from old vines with appealing weight and depth.

To judge by the reaction of diners (certainly including me) the star dish was a settesfoglie lasagne of artichokes, so called for its seven alternating layers of artichoke-stem bechamel sauce, sliced artichoke hearts, parmesan and hand-rolled pasta. It was quite the most lovely lasagne I’ve had in a very long time. Two DOCG Pignoletto Superiores didn’t really stand up to it: Manaresi Pignoletto Superiore 2017, slightly bigger of the two, was closer to the mark.

Finally, Bettini offered us superlative pork: capocollo of the local black pigs (a shoulder cut – not so far from pluma of Iberico pork) with intense, slightly sweet black garlic sauce. I feel a little guilty saying it but I preferred the reds that accompanied this to the more-prized Pignoletto. Manaresi “Flora Italica” Barbera 2016, DOC Colli Bolognesi proved an irresistible barbera, lovely sweet fruit well balanced with acidity. But Podere Riosto “Grifone” Cabernet Sauvignon 2015, DOCG (go figure) Colli Bolognesi was perhaps the better match for the pork: rich and fine grained in a way that almost put me in mind of a Bolgheri, but still with a nice spine of grippy tannins.

Does Italy really need all of its 74 DOCG areas, never mind the DOCs? Is Colli Bolognesi Pignoletto a more noble expression of the grechetto that goes into Orvieto Classico and other Umbrian whites? Can I now tell the difference between white Voghiera garlic and its Catalan or Breton equivalent? I’m not sure it really matters. They’re all part of the local patchwork that makes up Italy’s gloriously anarchic food and wine map. And to judge by this dinner, that tradition of variety is in rude health.

21 May 2019

Main pic: Donatella Agostoni of Manaresi with some of their grapes (from Manaresi website)

0 notes

Text

What Ottolenghi did next

IN setting the flavour of our times, this decade has been Yotam Ottolenghi’s. The Israeli-born chef and his Palestinian business partner, Sami Tamimi, first set up shop in Notting Hill in 2002. But it was the publication of Ottolenghi’s second cookbook, Plenty (2010) and the opening of Soho restaurant Nopi the following year that shot him to ubiquity. Since then he has launched a series of celebrated cookbooks and TV shows. And his fame is international: when a New Yorker friend visited me last week, the top of her to-do list was eating at Ottolenghi’s restaurants.

His significance is, however, much greater than that: Ottolenghi has quite simply changed the way we (or at least the metropolitan middle class) eat. It’s a point already made unimprovably by the Sunday Times’s brilliant Marina O’Loughlin. Put it this way: what were until recently obscure Levantine ingredients such as za’atar, sumac and pomegranate molasses have become everyday in a way that once took, say, balsamic vinegar 20 years. There are now Waitrose own-brand versions of all three ingredients. Meanwhile Ottolenghi is surely responsible in part for the governing restaurant trend of small plates, and for the breakthrough of other Israeli-inspired eateries (The Barbary, Honey and Smoke). And I can’t think of a single book since the River Café Cook Book (1995) that has so thoroughly changed my own kitchen.

Yet Ottolenghi resisted the temptation to open more restaurants after Nopi. Then last summer he launched Rovi in Fitzrovia; on the principle that I don’t try any fancy restaurant until it has O’Loughlin’s approval, I only made it there last week. And it is magnificent.

It’s a bigger space than Nopi, but with even greater attention to detail: airy, pale wood and comfortable, vaguely Nordic seating. We sat at the bar. But you’re here for the food: and as a succession of taste sensations, I’d put it up there with, for example, a visit to Albert Adrià’s celebrated Barcelona tapas joint, Tickets.

The dishes came as a cascade of delights, with us trying to pin down flavours and figure out just what was in front of us and in our mouths. This was a meal where most of our talk was about the food.

Thus we started with snacks of carrot jerky with gooseberry boshi, smoked labneh and chilli, and duck pastrami with a selection of pickles (cabbage, endive, purple carrot and something neither we nor the bar staff could identify; both dishes pictured above.) No, I don’t really know what gooseberry boshi is either: it’s hard to Google as there’s some Nintendo character of that name who gums up searches (this is food that demands a fair bit of at-table googling.) But in any case, the sum of these flavours almost defies description.

Indeed vegetables dominate the mostly small-plates menu. It’s another key part of Ottolenghi’s influence: he’s taken vegetarian food from Guardian self-righteousness – a column there was the genesis of Plenty – to bleeding-edge London foodie hip.

Using the kind of Levantine flavours we’re familiar with from him, Ottolenghi (or rather his chefs – he’s not in the kitchen here) delivers hugely satisfying vegetable dishes such as celeriac shawarma with bkeila, a spinach herb paste, and fermented tomato (pictured above). I yield to no-one in my love of lamb shawarma but this was just about enough to turn me veggie.

The big shift from Nopi is the Asian influences here: furikake (Japanese fish/seaweed seasoning), kosho (a seasoning paste with chilli), fermented black vinegar and (presumably) boshi. We loved the tempura stems and herbs with Szechuan, mandarin and lime-leaf vinegar, and a side dish of spring greens with dashi and sesame; and asparagus with wild garlic, burnt butter, lemon kosho and jalapeño.

But as those combinations suggest, these are dishes and flavours that are genuinely hard to describe – and the menu provides only an approximate guide. Take the delectable “beef carpaccio (grass fed), Jerusalem artichoke, Crowdie” (pictured above). Never mind the quality of ingredients – pink, melt-in-your-mouth rounds of beef – or that I’d never have identified the sweet-sour artichoke for what it was (pickled?), or the oddness of pairing it with a Scottish soft cheese: as an ensemble, it delivered flavours and textures greater and more unexpected than its parts.

The same is true of the astonishing desserts – something I am rarely tempted to order. Eventually we plumped for rhubarb and rose doughnuts with vanilla cream and pistachio, and five-spice pumpkin and apple fritters with clementine, buckwheat and coconut sorbet: both combinations of wonder. We left eager to taste the rest of the menu.

The wine list is fascinating and appropriately sparky, though for me it somehow doesn’t quite hang together. It’s fairly pricey: there isn’t much under £40. It is also heavy on natural wines: with our opening snacks I drank Nando rebula (ie ribolla gialla) Blue Label 2017. Having a fairly obscure Slovenian orange wine like this on a list carries a certain kudos amongst today’s hipper London sommeliers; I just thought it cidery. As for the Jurschitsch Belle Naturale grüner veltliner 2017, Kamptal, also orange (though not on the list as such), I sent it back: not only did it bear no resemblance to any GV I’ve ever tasted, it was just an unbalanced mess.

But tasting one’s way through such a list is an adventure – especially with bar staff as good as these. Ciù Ciù “Falerio” 2018, Oris Bianco, a trebbiano/pecorino-based white from the Marche region, also had some skin contact but was utterly charming. The La Raia Gavi 2018 (organic) was much more classic, beautifully clean.

Among the reds, there is Alfredo Maestro’s well-balanced Valdecastrillo Ribera del Duero 2016 by the glass. But the real discovery is Cremisan Baladi 2017, Palestine, made on an estate owned by a Catholic order in the West Bank by a Christian Palestinian winemaker. From the local baladi grape, it’s dark, juicy, not unlike cinsault, with a touch of oak. Elsewhere on the list is a trio of beautiful nebbiolos, at a price (including ones from the rarely seen Ghemme and Gattinara areas in Lombardy) as well as Christian Tschida’s intriguing and very individual Felsen II syrah 2016, Burgenland.

Rovi triumphantly takes Ottololenghi’s middle-eastern fusion cuisine to a new level. It will be interesting to see whether it spawns a cookbook. My instinct is that this is the kind of food that you simply cannot prepare at home; then again, maybe in three years’ time we’ll all be incorporating koshu and furikake into our dinner-party dishes? You read it here first.

Rovi, 59 Wells St, London W1A. 020 3963 8270.

6 May 2019

1 note

·

View note

Text

On natural wine, restaurant markups and class privilege

SHOREDITCH has shape-shifted out of recognition since I worked nearby 20 years ago. Gone are the print shops, greasy boozers and, well, working-class people. Instead it now thrums with cocktail bars, street food, beards of a size little-known pre-2000 outside the Canadian lumber industry – and places specialising in natural wine.

On Leonard St last week I was reminded of some of the joys and challenges of natural wines at St Leonards restaurant and bar and Passione Vino wine bar and shop.

St Leonards’ fairly large wine list has been praised for its natural/biodynamic bent and there are indeed interesting bottles there. But it’s expensive: I counted only around 10 wines under £50, with chunky mark-ups throughout.

Sure, restaurants have to mark up their wine to help cover their overheads: you’re paying for the surroundings in which you enjoy your glass, not just what’s in it. My rule of thumb is that if anything costs twice retail price or less, you’re getting a good deal.

But Felines Jourdan’s serviceable but not exactly starry Picpoul de Pinet at £37/bottle? (Wine Society retail price: £8.50). And while I’d have been more tempted by Apostolos Thymiopoulos’s superb Earth and Sky xinomavro (on the website list though not in stock), at £90 it would have hurt, not least since I bought a bottle from the Wine Society a couple of months back for £21.

Partisans for natural wines tend to present them as a rebellious, righteous riposte to a stuffy wine world. Such wines are rarely cheap, made in small quantities with labour-intensive techniques. Yet with a roughly three-times-retail mark-up, that means that a tasty but essentially rustic wine such as Vigneti Tardis Venerdi Bianco fiano/malvasia 2017 comes in here at £12/glass, or Anne-Claude Leflaive “Clau de Nell” Loire grolleau 2013 at £70 a bottle.

And I’m sorry but there’s no way around it: dropping £70 on a bottle of wine is about as about as hip and anti-elitist as Nigel Farage.

So we settled for a bottle of alright-but-unremarkable organic Aroa garnacha 2017, Navarra at £40.

Down the road at Passione Vino, also specialising in natural/biodynamic wines though only Italian ones, it was a different story. This is a fantastic Italian range, the kind of list instantly recognisable as the work of someone with both huge knowledge of and passion for the wines. Tuscany is well represented but there are bottles from all over Italy, including plenty of denominazioni I’d never heard of. I doubt, for instance, that you’d find a better selection of Franciacortas anywhere else in London.

I’m sure Passione’s overheads are a good deal lower than slick St Leonards’: it’s essentially a slightly battered enoteca in the Italian tradition, with just a few tables (and a large communal one downstairs) and some snacks such as salume. Still, you can drink the bottles off the shelves around you in the bar at roughly a 50 per cent mark-up – and with a slew of fascinating wines around the £20 mark, that means plenty of pretty serious drinking at under £35 a bottle.

We decided that another whole bottle at this point in the evening might be de trop; Passione has no set list of by-the-glass wines, but a number of bottles open at any time. I tasted a defiantly leftfield Ruschi Noceti "La Costa" 2008, IGT Val di Magra, from the very obscure Ligurian red grape pòllera: fragrant, mature but still grippy, very individual.

Next up was Terre Nobili “Cariglio”, IGP Calabria (£8), from the little-known Calabrian grape magliocco: deeply coloured, wonderfully rich and smooth, lovely balance. A real discovery.

Finally, I had a glass (alright – two) of Casale Chianti Riserva 1999, Colli Senesi (£9). I have to say this was the finest aged Chianti I’ve had in a very long time, gloriously mature and balanced, still with plenty of fruit and power. I’ll certainly be back soon, even though they will have no doubt run out of it by the time I get there.

We’ll always have to pay more for good obscure and biodynamic wines. How much more is fair, though, seems to me to deserve more debate than it presently gets in the British wine world. And while we’re at it, we might ask how far, simply by sporting a long beard, you can cancel out the class privilege implied by splashing the average UK household’s weekly food bill (2017: £91) on one bottle.

28 April 2019

0 notes

Text

Balkan beauty: restaurant review of Peckham Bazaar

THE insularity of many London neighbourhoods is notorious – and Herne Hill is one of the most villagey of the lot. Even after living there 20 years, I am completely lost in Peckham, a 15-minute bus ride east. But what has finally made me ashamed of this fact is my discovery of the fantastic Peckham Bazaar around six whole years after it first opened.

The restaurant advertises itself as a “pan-Balkan mezze and grill” – but that comes nowhere close to describing the sophistication of this food. The inspiration for the daily-changing menu of smallish plates is drawn from Greece, Turkey, Albania and the former Yugoslav states, as is the wine list (of which more later). But this is not Greek, Turkish or (thank God) Serbian food. And it’s all executed with a freshness and zing to the flavours that call to my mind the best of Lebanese mezze rather than their Turkish or Greek variants.

Thus “baked feta, marinated beetroot, skordalia, walnut, capers, chicory” has pretty clear Greek influences but is greater than the sum of its parts. Kourkoubines are a kind of small, filled pasta from the island of Evia and around: but I’m not sure locals would recognise Peckham Bazaar’s incredible take on them with roasted butternut squash, caramelised cauliflower and aged graviera cheese.

And as for the fabulously tender marinated grilled octopus, served with baba ganoush and onion and parsley salad: I yield to no-one in my chauvinism for things Greek but this was simply way better than any octopus I’ve had in Greece (or anywhere else, in fact.)

There is similar brilliant invention in dishes drawing inspiration from further afield. Pastilla is a glorious Moroccan pigeon/chicken pie: but the lamb neck, almond and prune pastillas here (served with with celeriac puree, soft-boiled quail’s egg, treviso and herbs) have travelled a very long way from Marrakesh. Likewise the Egyptian stuffed quail with chickpea, apricot and saffron tagine.

We ordered almost the whole menu – there were five of us, there to celebrate my birthday. Suffice to say that when we had finished the last dish – slow-braised shoulder of Welsh spring lamb, gigantes plaki, marinated peppers, ktipiti (red pepper-cheese dip) - we were blissfully sated. (Others in the group were possibly less full, since they then order and raved about the desserts.)

As for the wines, this is a fascinating and idiosyncratic list ranging from Italy to Georgia, though with Croatia and Greece as its mainstays. We enjoyed Dafnios liatiko 2016, a fairly obscure Cretan red from Douloufakis Winery, and Vina Skaramuča plavac mali 2016, a red from Dalmatia. More unusual still are the wines from Ktima Ligas, a natural Greek producer in Pella, to the north east of Naoussa. Their Xi-Ro is a highly unusual red-white blend of 90 per cent xinomavro and 10 per cent roditis: aromatic and complex. As for Ligas’s “orange” Pata Trava xinomavro 2017, I don’t know quite how they regulate skin contact to get this delicately coloured a wine with so little oxidation, but it’s serious: fragrant and quite haunting.

Peckham Bazaar also serves Greek beers from the excellent Septem craft brewery on Evia, and a fine non-aniseed tsipouro (Greek grappa). I’d have gladly lingered over a second or third glass of the latter in these very relaxed surroundings but more sensible heads prevailed. I’ll just have to return soon.

Peckham Bazaar, 119 Consort Rd, SE15. 020 7732 2525.

Non-plate pics are from restaurant website. Rubbish ones of dishes: mine

24 April 2019

0 notes

Text

The right way to run a wine business

I’VE raved before about the wines of both the Wine Society and Lea & Sandeman, so it won’t come as any shock that I enjoyed their Spring tastings this week. But I was struck at both events - with many wine people saying how much they agreed with my rant about Naked Wines (scroll to the blog post below) - by the diametrically opposed approaches of Rowan Gormley’s outfit and these merchants.

In some respects, L&S fit the posh-wine-trade image that Naked claims to set itself against. They sell lots of expensive Burgundy and other fine wines online and at their four west London shops; you won’t find much under £8. Their range is dominated by Old World wines, many from famous regions. And they are - would it be unfair to say, posh? Put it this way: I don’t imagine anyone there would bat an eyelid if you came to work in red cords and/or a blazer. I’ve certainly never seen Charles Lea with his shirt untucked.

Yet quite aside from the fact that their staff are actually friendly and knowledgeable, L&S’s old-fashioned approach to wine buying offers a much better deal to both consumers and producers than the Naked model. And while the Wine Society is a very different beast - a major online/mail-order player with £97 million in sales in 2018 - its ethos when it comes to both buying and selling isn’t so far from L&S’s.

Both ask fair prices for what they sell, and don’t engage in any sales gimmicks. True, L&S don’t have the kind of buying power and economies of scale of the Wine Society or of any large outlet: you’re not going to get dirt-cheap wines there. But while the Wine Society is big, it’s a members’ cooperative: it makes no profit, putting everything back into the business. And neither merchant wastes vast amounts on marketing and advertising (Naked’s spend on winning new customers alone last year was £14 million.)

Meanwhile L&S, the Wine Society and some other independent importers give small producers the kind of deal those farmers actually need: after seeking out talented winemakers, on the ground, they let them make wines the way they want to, pay fair prices, and build relationships over years. They don’t pull stunts like the ones from some British supermarkets that many French and Spanish producers have complained to me about, where after getting a listing, the store then demands big price reductions to pay for promotions, or just cheaper wines full stop (I should add that French and especially German supermarkets’ behaviour is reportedly similar.)

What kind of wine do you get as a result of this laborious, serious, ungimmicky approach? You just get quality. It doesn’t mean a staid or conventional range: the Wine Society consistently champions new and different wines. And while L&S’s range is a little more conservative, that doesn’t mean predictable: for example, the red Riojas they showed this week were a bit leftfield for my taste.

But most of all at both tastings, I was struck by the brilliant, textbook examples of given appellations and grapes - not particularly daring or boundary-pushing, just lovely wines that tasted of where they were from and of the care that had gone into making them. The following were a few favourites. Prices quoted for L&S wines are with the mixed-case-of-12 reduction.

Domäne Wachau Federspiel grüner veltliner 2018, Wachau (WSoc, £9.95 - this new vintage from 26 April)

A classic example of Austria’s signature white grape: this is juicy and clean with bags of fruit - and hints of lime and white pepper. Good value at this price for this sort of quality.

Château de Pierre Bise, Clos de la Coulaine 2016, Savennières (L&S, £18.50)

I’m not a big chenin blanc fan but this is utterly delicious, the best Savennières I’ve had in some while: elegant, mineral, complex yet clean. A seriously classy Loire white.

Maga Karma do Sil Godello 2018, Ribeira Sacra (L&S, £12.50)