Text

Playing Dragon Age: Origins

Sten: I killed that family.

Me: 100000% innocent.

Alistair: But, he confessed.

Me: Innocent.

Morrigan: He wants to die.

Me: We should save him.

Sten: Leave me alone.

Me: I’ll save you.

Everybody: He’s a murderer.

Sten: I’m a murderer.

Me: I GOT THE KEY!

16K notes

·

View notes

Text

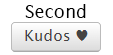

Are you frustrated you can't leave second kudos on AO3? or third kudos? or whatever-who's-counting kudos?

Well, have I got the html for you!

Plop any of these in a comment (by copy&pasting the code) to make an author's day and show your appreciation!

Second kudos: <img src="https://i.ibb.co/tHMjbb6/second-kudos.png" alt="second kudos">

Third kudos: <img src="https://i.ibb.co/52bggQH/third-kudos.png" alt="third kudos">

nth kudos: <img src="https://i.ibb.co/6y7qGtC/nth-kudos.png" alt="nth kudos">

yet another kudos: <img src="https://i.ibb.co/wKtcj0s/yet-another-kudos.png" alt="yet another kudos">

It will look something like this (and will be transparent with white outline on dark backgrounds):

Feel free to spread and use these as much as you like! (and if you have ideas for other variations, let me know ✌️)

116K notes

·

View notes

Text

i also think it's just worth examining how much more grace bioware gives to their White Blonde Men in their narratives. cullen and vivienne have similar positions regarding circle reform. but where vivienne is treated like an opportunist that's just interested in consolidating power for herself, cullen is always treated like a victim of circumstance. and it isn't just him. alistair has SO MUCH to say about mages, 90% of which is very clearly not sympathetic, yet the game makes every effort to contextualize it in such a way that it's easy to handwave as good intentions with unfortunate prejudices, rather than something that deserves a more critical examination. which isn't necessarily Bad. it's not like alistair's opinion on mages plays any significant role in the narrative, nor is it treated as a real issue for his relationships. but compared to sten? to fenris? like bioware very much has a pattern of putting a lot more work in making their white characters more immediately relatable while letting characters that fall outside of that scope suffer the burden of having to Earn any kind of audience sympathy

364 notes

·

View notes

Note

how many of your da protagonists are POC?

none

1

2

3

4

Don't forget the Orlesian Warden-Commander!

175 notes

·

View notes

Text

“elfy hurt too much”

Trying something a little different, folks. What I have for you today is some rare dialogue that I found by digging through the game file with a mod maker program. In order to see this dialogue, you have to be a female Lavellan, romance Sera, and break up with her after “What Pride Had Wrought” over your differing religious views.

When you speak to her at the Winter Palace in Trespasser, after you visit the Ruins the first time, you can have the following conversation:

Inquisitor: When you start talking about elves, it’s hard to tell if it’s about them or about you.

Sera: Ugh. And when you do that, I don’t know if we’re talking about what we’re talking about, or if we’re talking about Mythal. Again.

Yes, I was a bit shit. No, it wasn’t fun. Yes, we maybe could have compromised. No, it isn’t about elfy stuff now.

Inquisitor: Now you think you could compromise? You drew a hard line at the time.

Sera: Well, now I could slap your arse and say, “That’s very interesting.” But back then, “elfy” hurt too much. Because I was never the right kind.

It would have been bad, anyway. It’s like Giselle, patting heads but moving the Maker higher. Saying one thing but meaning another.

We were grand but kind of broken. So we stopped. And maybe that’s good? To be stupidly true, even if it ends things?

Inquisitor: A shame it ended like it did.

Sera: It really is. We’re alike on that.

So…friends? Because everything seems like it’s ending, and maybe it’s been too long to sit on this much growly?

Inquisitor: I think so too, Sera. Time to let it go.

Sera: If you’ve no plans later, do you think we could survive a drink for every time things were stupid?

Inquisitor: (Chuckles.) Unlikely.

319 notes

·

View notes

Text

there is an underlying implication that part of justice's motivation for wanting a living host is that he wanted to know what the big deal about cum is. and we just have to live with this.

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy Neve week for all who celebrate! ❄️✨

262 notes

·

View notes

Text

"a soul can never be forced upon the unwilling, you were never in any danger from me" is, I think, emblematic of Mythal in a really juicy fucked up way.

We know that possession in DA requires a 'yes' in (most) circumstances. But we also know that that consent can be coerced; coerced consent is actually how 99% of demons operate.

It's probably true that Morrigan would have to say yes. But the way in which Flemeth raised her was designed to give her absolutely no choice in the matter. We see, consistently, that Flemeth emotionally abused Morrigan over and over. She kept her purposefully isolated from her peers, consistently needled and put her down, and with Morrigans mirror literally shattered a symbol of Morrigans individuality. Flemeth even has special robes for Morrigan (robes of possession) which reduce her willpower. In the fade, Morrigan says the spirit pretending to be Flemeth is acting more like her mother only when it physically slaps Morrigan suggesting a level of physical abuse.

In DAI, just before she says the famous 'you were never in any danger from me' line... Flemeth literally gives a horrid little ultimatum to Morrigan that proves just how manipulative she is. She literally says; I will take your son from you forever OR you can have him back but you'll never be safe from me as long as you live. And Morrigans response 'i will not be the mother you were to me' also points at the abusive Morrigan suffered under Flemeth.

The way in which Morrigan was raised then, was designed to create a person who would say yes, who had been groomed and emotionally (perhaps even physically) manipulated all her life for this one purpose.

Mythal seems to be characterised in a similar way; she is benevolent, the 'best' of the gods, and she believes herself to be compassionate. And yet, she kept slaves. You can drink from her well but once you do your bound to her will and will do anything she says. She sees herself as the good one, good to the people, but she's still willing to use them.

To reduce Flemeth down to a loving mother who never meant anything bad for Morrigan because of a single line she says (which itself is a manipulation) is to deny a lot of depth to Flemeth, Morrigan and Mythal.

728 notes

·

View notes

Text

Your friends and family should be your second priority. Your first priority should always be hot evil women

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

I have thoughts about romance in Dragon Age!

Romance here has nothing to do with dating your companions. We’re speaking in the literary sense, in the sense that King Arthur and Moby Dick and One Piece are all romances. There’s a long legacy for this sensibility in fiction that’s seen a shift from often fated(doomed) cycles wherein a hero embodying a particular virtue is up against an enemy embodying its opposite, to the modern-adjacent romantic novel and arts movements that saw that conflict move inward so that a protagonist/deuteragonist/antagonist embodies both in a transparently internalized sense. We still go on a quest of some kind, defined by the subjectivity of our protagonist who must ultimately undergo symbolic death on the road to the promise of some form of-typically social-change. The inward turn of Romanticism in the novel has since complicated what the triumph of virtue looks like, often locating it within the personal and emphasizing a more compromised vision of social order.

So, when I say Dragon Age became more romantic, I mean the series became more and more idealized and evocative in its fantasy, more invested in the realm of emotions, archetypes, and ideals across the first three games. It romanticized its subjects. This is reflected at the level of art direction (shout out to @wardensantoineandevka for making me think about all of this with her observation that Warden uniforms are quite romantic in their lines), character arcs, and an emerging cyclical structure focused on opposing sets of virtues and flaws.

But let’s back up a step or three. Because Origins is not a romance. We do have something of the form. A hero goes on a quest through a series of adventures culminating in symbolic or literal death and triumph. They can sort of even rescue some maidens (who are not always maidens). Origins’s base game is not actually super interested in sending you on an adventure or in any particularly specific idealized virtues, though. You could make an argument for sacrifice or desire, but this is nascent and murky in execution. We’re lacking the coherent positional identity for our protagonist/s because our enemy is a motiveless mindless horde. The game is more interested in making jokes about the adventure and referencing other adventures in other media. We sometimes call this approach burlesque in the literary world. Don Quixote is a true burlesque of courtly romance. So, Origins is doing a bit of pop-postmodern lite burlesque regarding fantasy RPGs, which have their roots in D&D which is already a lite pastiche of mid-century adventure fantasy, which in turn has its roots in romance for the most part. This is all baked-in, essentially. Origins doesn’t truly commit to any approach (if you want the game that does, that game is DOS2). This changes in Awakening, which–though just as funny–isn’t substituting references and silly asides for narrative. We can largely thank better clarity in the character writing and more nuanced enemies for that.

Dragon Age 2 is a mostly unapologetic tragedy, and it’s certainly fairly romantic. It’s the strongest Dragon Age game for plotting, and this frankly brings everything into focus for the series. This is where we start taking our ideals seriously. We can sketch a fairly clear set of themes around specific virtues/flaws like anger, justice, and curiously daring. Justice, retribution, vengeance, ambition, “audacity.” The oft-lauded characters of 2 are actually fairly thinly sketched. But the plotting is so strong and the characters so well integrated into plot and theme that they and their internal conflicts shine anyway. And a nascent inverted romance form is present in Hawke’s journey though repeated losses that force them into an ultimately doomed quest to recover their family’s standing. The symbolic death here occurs in the deep roads, particularly if you’ve taken a sibling along. The sibling may be blighted, but Hawke is the one who ‘dies’ and yet must carry on. This is not a traditional romance, but it IS using the form in interesting ways that are reminiscent of romantic novels like Ivanhoe.

I had previously and incorrectly claimed that all Dragon Age games have weakly motivated enemies, but both Meredith and Corypheus are great actually,* so consider this happy acknowledgement of my error. Structurally, both 2 and Inquisition give their antagonists little breathing room, but that’s not actually much of an issue if we’re reading these games as romantic. What’s essential is that the enemy/antagonist embodies the conflict as much as the protagonist via an opposing set of flaws, something both games accomplish.

Inquisition is, of course, so sincerely romantic it’s inescapable. Plotting is weaker here, but themes and character arcs are fully in line with the form. The Inquistor’s path is one long journey through symbolic death regardless of how you RP them. Hope and faith are our central virtues, and loss and corruption are positioned as their opposites. It’s no accident that we fight so many despair demons in this game. Certainly not accidental that our A-plot villain is a man-turned-monster whose faith has been broken and whose literal body is corrupted by an ancient curse. And of course, we spend the run of the game with something like a deuteragonist whose story is quintessentially that of the tragic hero, born from corruption of purpose and loss of hope in a move that retroactively clarifies even Loghain’s function in Origins.

So much of this coheres around the central entries having a sincere interest in faith, both as an ideal and as an institution that governs lives. That’s a lot of fantastic baked in conflict that aligns itself easily with a romantic formula. Andraste herself is a fundamentally romantic figure. A woman who came from nothing to lead a crusade on a quest for freedom. Who died quite literally but also symbolically, prophesied to return. She’s Jesus, but she’s also King Arthur and Joan of Arc. An intensely tragic and romantic hero embodying a pure ideal and carrying the weight of promised freedom in a fundamentally un-free world. The tragedy of the chantry becoming a tool of oppression is inevitable in this kind of setting. There’s no other way for the contrast of her promised social upheaval to carry dramatic and emotional weight. This is why doomed cycles are a fundamental element of romance, something that really comes to the fore with the context Ameriden provides in Jaws of Hakkon. We see the cycles of conflict and loss and persistent virtue, we see it particularly in the repeated motif of love making monsters/heroes of people and in triumphs beyond death.

*Loghain is fine of course but our themes are generally muddled in Origins because his motives are locked away in a novel, and the darkspawn are our actual enemies. Say what you will about Corypheus, he actually got set up for his role in Legacy and has in-game clearly presented motives that are on-theme in Inquisition. We don’t need a romantic antagonist to be a massive plot driver. We do need them to be a coherent themes driver without their motives tucked away in a novel.

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

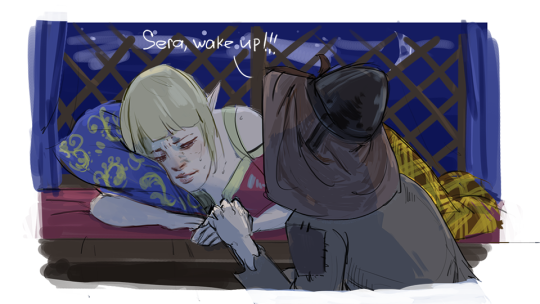

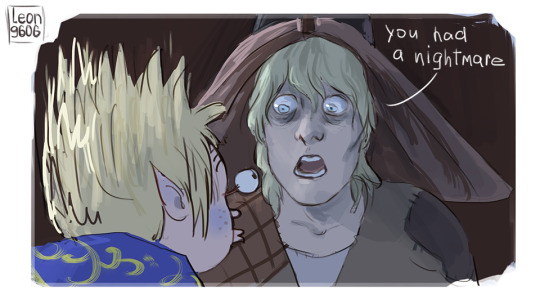

I'm drawing at snail pace. Work really fucks me up at the moment...

203 notes

·

View notes

Text

the worst thing is when fandom ruins a character for you that you really like

182 notes

·

View notes

Text

why do they call this a brothel? does it have something to do with broth?

189 notes

·

View notes