Text

Must-See TV (Episode 2)

And now, for the art history.

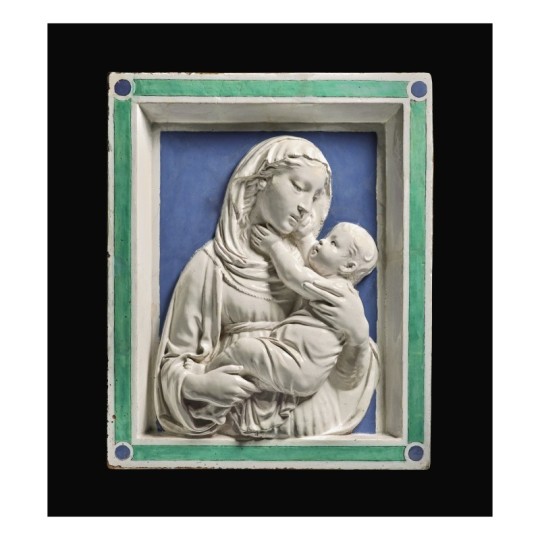

Luca della Robbia (Italian, 1399-1482), Madonna and Child, ca. 1450, tin-glazed terracotta (18½ x 15¾ in.). Photo credit: Sothebys.com.

There were a number of items in Sotheby’s January 28 sale that caught my attention because of their association with Hyde pieces. The first was Lot 2, Luca della Robbi’s terracotta relief, Madonna and Child. Luca (1399-1482) founded a multi-generational family workshop that was famous for its terracotta sculptures covered in a gleaming, pure, white glaze—its formula, a closely-guarded family secret—that made the fired clay pieces impermeable to the elements and gave them the appearance of much more expensive marble. The reliefs were cast in molds, allowing for a degree of mass-production that expanded the clientele for such fine works of art to include the successful merchant and banking class of Renaissance Italy’s major cities.

Luca della Robbia (Italian, 1399-1482), Madonna of the Lilies, ca. 1450-1460, tin-glazed terracotta (20 1/4 × 16 1/8 in.) The Hyde Collection, Glens Falls, New York, Gift of Charlotte Pruyn Hyde, 1971.99. Photography by Michael Fredericks.

Like The Hyde’s Madonna of the Lilies, the Sotheby’s relief was intended for the domestic market. It was undoubtedly used in the home as the focus of private, family devotion to the Virgin and Christ Child, and indeed, Sotheby’s expert Giancarlo Gentilini proposes that the relief was commissioned by Bosio I, Count of Santa Fiora in Tuscany for this wife Cecilia, sometime between 1439 and 1451.

It is striking how intimate the viewer’s relationship with the Madonna and Christ Child is, more so than in our terracotta. So high is the relief carving, the divine pair actually breaks out of their tightly constrained space into our world. The sculpture affirms the Christian belief that God was incarnate in Christ, here the robust child, tenderly held in his mother’s arms. His divinity and her purity are expressed through the terracotta’s unblemished white glaze.

Surprisingly, the two reliefs “met” once. They were both included in an exhibition at the Detroit Institute of Arts in 1938 that was curated by William Valentiner, the museum’s director and Mrs. Hyde’s art advisor. Both sculptures have been praised by experts as being “autograph;” that is, they are so fine in their execution, even though other examples survive, that the hand of the master, Luca, has been discerned over that of his workshop assistants.

Lot 14, Sano di Pietro, Nativity.

Sano di Pietro (Italian, 1405-1481), Nativity, tempera and gold ground on panel (20 5/8 by 15 7/8 in.). Photo credit: Sothebys.com.

There is a clear resemblance between the form of Virgin Mary’s head in this depiction of the Nativity and that of the Archangel Gabriel’s in The Hyde’s panel that formed one half of an Annunciation scene.

Sano di Pietro (Italian, 1405 - 1481), Angel of the Annunciation, ca. 1450, tempera and gilding on panel (14 1/2 × 13 1/2 in.); The Hyde Collection, Glens Falls, New York, Bequest of Charlotte Pruyn Hyde, 1971.44. Photo credit: Mclaughlinphoto.com.

Sano di Pietro (1405-1481) was a leading painter in Siena in the first part of the fifteenth century. In the Sotheyb’s panel, we have the chance to examine his use of color and composition in constructing narrative scenes. The primary storyline, Christ’s birth in a stable, dominates the foreground. The secondary narrative, the annunciation to the shepherds, occurs in the middle distance. The principal figures, including the ox and ass, are modeled with evenly modulated light. They have a sense of early Renaissance volume and weight lacking in the rather flimsy Gothic architecture of the stable. A brightly colored choir of angels watches over the Christ Child, and God sends down the dove of the Holy Spirit in a shaft of divine light to illuminate the newborn, who lies in an aureole of straw and light that signals His divinity.

There is some debate as to whether this panel was part of a small chapel altarpiece or intended for use in a domestic setting. Last year, a student from Florence wrote to The Hyde asking for particular information about our panel. She thought she might know the altarpiece from which our Angel came. The piecing together of dismembered altarpieces, often by studying physical elements such as the thickness of the panel and the pattern of growth rings, is an emerging field of research. It educates art historians in the more practical and physical aspects of art production. I have tried to follow up, but, as of yet, still await news of her findings.

Lot 15. Sandro Botticelli, Portrait of a Young Man Holding a Roundel.

Sandro Botticelli (Italian, 1444-1510), Portrait of a Young Man Holding a Roundel, n.d., tempera on panel (23 x 15 ½ in.). Photo credit: Sothebys.com

This is the auction item that everyone is talking about. It sold for $80M (with commissions, etc., it came to $92,184,000).

There was little drama in the sale itself. The opening bid was $70M. The sale ended five bids later, in increments of $2M, at $80M. With commissions and fees, the work topped out at over $92M, the most ever spent for a Florentine Renaissance Master.

As in the della Robbia discussed above, the artist uses the architectural framing within the piece to push the figure forward. Through the illusion of a finger extending beyond the painted lower ledge, Botticelli suggests that the young man is real and actually standing in the viewer’s space. Elegance is the watchword for this painting. It is present in Botticelli’s use of line and form and in the artist’s self-assurance and that bestowed upon the figure and character of the sitter. These are qualities that we can sense in The Hyde’s small predella panel depicting the Annunciation.

Sandro Botticelli (Italian, 1444-1510), Annunciation, ca. 1492, tempera on panel (7 x 10 9/16 in.). The Hyde Collection, Glens Falls, New York, Gift of Charlotte Pruyn Hyde, 1971.10. Photography by Joseph Levy.

Mary reacts in a graceful and demure manner as Gabriel glides in to the loggia where she was reading her devotional book. The angel’s robes flutter, perhaps a little fussily. Where our sadly abraded panel gives only a hint of Botticelli’s command of delicate shades and tones, the remarkably well-preserved Sotheby’s portrait gives ample evidence of Botticelli’s mastery of tempera painting.

The roundel the young man holds is a very peculiar detail. It is a separate work of art by the Sienese artist Bartolomeo Bulgarini from roughly a century earlier, and it has been pieced into Botticelli’s panel. Quite what Botticelli meant to signify by this is debated by scholars. Was he suggesting a genealogical link between the two, a shared character trait, or perhaps a strong devotion by the young man to the unidentified saint?

School of Haarlem (Dutch, 1600-1699), Portrait of a young man holding his gloves and wearing a tall hat, his arm akimbo, oil on panel, an oval, (10 by 7 ½ in.). Photo credit: Sothebys.com.

I was curious about the next lot, rather cautiously identified by Sotheby’s as “School of Haarlem, Portrait of a Young Man Holding his Gloves, circa 1615.” I thought immediately of the small oval portrait in Hyde House dining room that we now attribute to the Circle of Frans Hals.

Circle of Frans Hals, (Dutch, 1580-1666), Portrait of the Artist's Son, ca. 1630, oil on panel(7 7/16 × 6 1/2 in.). The Hyde Collection, Glens Falls, New York, Bequest of Charlotte Pruyn Hyde, 1971.21. Photography by Michael Fredericks.

Like ours, the Sotheby’s painting was once thought to be by Frans Hals himself. Hals (1580-1666) is famous for portraits that both in the manner of their execution and in the personality of their sitters, are full of dash and swagger. In the catalogue entry, Sotheby’s favored an attribution to a contemporary of Hals, Willem Buytewech (1591-1624). The market didn’t agree. Bidding started at $30,000 for this small oval work that measures 10 x 7½ inches. It finally came to a stop after helter-skelter bidding at $390,600 (with fees)! There were plenty of bidders, who evidently thought this to be by Frans Hals. Would someone care to reconsider our painting? Like the Sotheby’s piece, the Hyde portrait was authenticated as a Hals by William Valentiner, but subsequently downgraded by several scholars, among them Seymour Slive, who reattributed the Sotheby’s work to Buytewech.

Hubert Robert (French, 1733-1808), View of a Garden with a Large Fountain and View of a Walled Garden Courtyard, n.d., oil on canvas (99¼ x 56¼ in.). Photo credit: Sotheby’s.com

It was a detail in Lot 39, the eponymous fountain in Hubert Robert’s View of a Garden with a Large Fountain, that caught my attention. It recalled to mind the vertical jet fountain in The Hyde’s drawing, Château in the Bois de Boulogne, ca. 1780.

Hubert Robert (French, 1733-1808), Château in the Bois de Boulogne, ca. 1780, graphite on paper (9 3/16 x 15 3/4 in.). The Hyde Collection, Glens Falls, New York, Bequest of Charlotte Pruyn Hyde, 1971.103. Photography by Steven Sloman.

Such powerful vertical jets of water first became popular in French garden design at Versailles, where they symbolized the power of the Sun King. By the eighteenth-century, pleasure rather than power was the primary objective of art, architecture, and garden design. Robert was popular among the French aristocratic elite for painting large-scale decorative schemes for their grand houses. He often depicted pleasure gardens, bucolic scenes, and romantic ruins. In 1778, the painter was appointed designer of the king’s gardens. In the Sotheby’s piece the vertical jet of water makes a suitable compositional focal point in a panel that measure 8’ 3” in height.

A similar jet fountain appears in a decorative room panel signed and dated by Robert in 1773, executed for the financier Jean-François Bergeret de Frouville. Exhibited at the Salon of 1775, it was entitled The Portico of a Country Mansion, near Florence, and is now in the possession of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Hubert Robert (French, 1733-1808), The Portico of a Country Mansion, near Florence, 1773, oil on canvas (80 3/4 x 48 1/4 in.). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Bequest of Lucy Work Hewitt, 1934, 35.40.2. Photo credit: Metmuseum.org.

In our drawing, Robert drew a actual fountain, one that dominated the parterre behind the Château de Bagatelle in the Bois de Boulogne, on the outskirts of Paris. The château was built by the Comte d’Artois, the brother of Louis XVI. Marie Antoinette had bet him that he could not build his little pleasure palace within three months. Designed by the architect Francois-Joseph Belanger (1744-1818) in the Neoclassical Style, the party house was constructed in just 63 days. Robert decorated its salle de bains with six panels that depicted the Italian countryside, classical buildings, and various forms of entertainment, like dancing, swinging, and bathing. These panels, too, now reside at the Met.

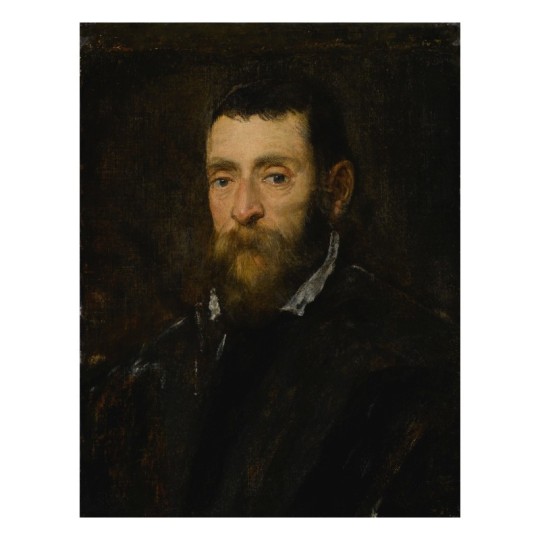

Jacopo Robusti, called Jacopo Tintoretto (Italian, 1518-1594), Portrait of a Bearded Man, 1560s, oil on canvas (23 3/8 x 18 in.). Photo credit: Sothebys.com.

Jacopo Robusti, called Jacopo Tintoretto (Italian, 1518-1594), Portrait of the Doge Alvise Mocenigo, ca. 1570, oil on canvas (21 1/2 x 15 1/2″); The Hyde Collection, Glens Falls, New York, Gift of Charlotte Pruyn Hyde,, 1971.49.

I have taken this last work out of turn, but I thought I would end with a comparison of hipster beards. Lot. 23 was Jacopo Tintoretto’s, Portrait of a Bearded Man. It was probably painted within a decade of The Hyde’s Portrait of the Doge Alvise Mocentigo (ca. 1570). The two share many traits. They are both portraits of self-possessed, wealthy men. Their dark somber clothing signals that. They dress according to the dictates of the style-setter for courtiers, Baldasare Castiglione (1478-1529), who wrote that “ the most agreeable color is black, and if not black, then at least something fairly dark.” Presented at only bust length, their torsos turned slightly away from the viewer but engaging directly with their eyes, these portraits convey a sense of intimacy and dialogue. The sitter’s face emerges from a dark background, its features modeled in warm lighting.

There are no known preparatory drawings by Tintoretto for portraits. He seems to have worked directly on the canvas before him. This would have appealed to his primarily male sitters because it undoubtedly reduced the number and length of sittings. As a side note, while it was acceptable for a man to sit or his portrait in a painter’s studio, it was not for a woman. Inconveniently for the portraitist and patron, the painter had to set up his easel and paint with oils in a female sitter’s house. Thus, the cost of a woman’s portrait was often more expensive. The conservative taste of the Venetian elite ensured that the compositional characteristics of this portrait had not changed in a generation. Where Tintoretto excelled was in the mastery and boldness of his brushstrokes and the accompanying speediness of execution. Notice, particularly in the Sotheby’s painting, the freedom and liveliness of the white brushstrokes with which he defines the shirt collar, distinguishes between the sitter’s beard and dark clothing, and spatially locates the different elements of the body within the otherwise ill-distinguished depth of the painting. Patrons valued Tintoretto’s masterly touches with the brush, the contrasts between areas of thickly applied paint and those where it is so thinly applied that one can discern the weave of the canvas. Working with accepted conventions, Tintoretto was able to convey something of what made his bearded male sitter unique.

There is always something of the wishful shopper, when I flip through a sales catalogue. But I am always excited when I discover something that relates to a work in our collection, and I ultimately never cease to marvel at the judicious purchases made by Louis and Charlotte Hyde.

#hydecollection#sotheby's#frans hals#sano di pietro#luca della robbia#botticelli#hubert robert#Tintoretto

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Must-See TV: Sotheby’s Sale (Episode 1)

https://www.sothebys.com/en/series/masters-week-1?locale=en

I’ve discovered a new form of engrossing pandemic-era online viewing. This week is my favorite week for January sales. Late in the month, various auction houses and dealers in New York host Masters Week. This year, despite a global pandemic, Sotheby’s outdid itself and watching the first of the sales today was, at times, edge-of-the-seat thrilling.

In a normal year, like the start of last year, I like to go down to New York on the weekend before the sales and preview the lots. The galleries at Sotheby’s and Christie’s are hung just like a museum. The walls are sometimes painted to enhance the paintings and the lighting presents them at their best. The only difference is that the labels include auction price estimates. It’s a form of glorious window shopping for me. I dream of what I could buy for the collection, if.... It is also an educational experience for me. For this is the week when scholars and curators of European paintings, sculptures, and drawings come to town from across the country, if not the world. You never know whom you might bump into in the salerooms. Often you can overhear or join, if you dare, an interesting discussion about the attribution, quality, or associations of a work up for sale. One thing to bear in mind is that not everyone agrees with the attributions of the auction house experts. Last year, I tagged along with my former professor, David Stone, as he dissected the Old Master drawings on offer at Christie’s. He introduced me to a curator from The Morgan with whom I discussed some Hyde drawings. All useful networking.

Christopher Easton (English, Exeter), Anglican Communion Cup, 1582, silver (6 3/8 in.). Chicago, Loyola University Museum of Art, Martin D’Arcy, S.J. Collection. 2013-05. Photography by Michael Troppea.

I tend not to attend the actual sales, which happen during the week. I have never myself bid at auction. When at the Loyola University Museum of Art, I really wanted to acquire a Protestant communion cup to contrast with the museum’s Catholic chalices, I had to commission an agent to bid for me. The auctions were in England and it took us two attempts to secure one. My agent, Wynyard Wilkinson, had to drive to opposite ends of the country to see the pieces and then bid for them. We were ultimately successful at a sale held by a small regional auctioneer, whom many collectors simply overlooked.

Today, there were a number of works I was interested to follow. The first six pieces were sold by the Albright-Knox Art Gallery in Buffalo. The museum has decided to refocus itself towards Modern and Contemporary art. Over the last few years, they have steadily sold off works that fall outside those parameters. Deaccessioning collection pieces is permitted under rather strict guidelines. The rules have been eased a little during the pandemic because of how badly lockdowns have effected museums’ incomes but, in general, a museum should only deaccession works that fall outside their mission or, are duplicates not of exhibition quality, or irreparably damaged. The funds generated should only be used to acquire more art.

The Master of 1518 (Flanders, active 1518), Adoration of the Magi, early 16th century, oil on panel (17 7/8 by 13 1/2 in.). Sotheby’s sale, New York, January 28, 2021, lot. 1. Photo credit: Sotheby’s.com

The Albright-Knox should be quite pleased. Four of the six pieces, among them the one illustrated here, sold for a total of $3,163,100. Some of that is commission for Sotheby’s, but still, the museum got roughly $2.5M to put towards new pieces of Modern and Contemporary art.

Had I been able to go down to the city and stroll the galleries, I may have seen or heard from others why two of Buffalo’s pieces didn’t reach their reserve prices. Were the reserves too high? Did collectors and curators not think either their quality or their attributions were quite right? Perhaps, they just weren’t to anyone’s taste. Selling at auction can be a gamble. You need at least two people, who really want a piece, to bid it up. The museum could wait to see if tastes and the market change, or it might negotiate a private sale after the auction.

At a normal sale, the auctioneer stands at a podium at the front of the saleroom. Major pieces hang on the walls and each piece is brought to the front, in turn, as the bidding takes place. For today’s sale, however, the auctioneer was in a room in New York on his own, watching screens linked to salerooms in New York, London, and Asia. In those rooms, in place of rows of bidders, there were tiers of Sotheby’s staff, standing physically distanced, holding telephone receivers to their ears. They spoke to invisible bidders, and, when instructed, called out a price, raised an arm, or simply shouted “Bidding.”

“What’s so gripping about that?” you ask.

I have learnt to sit towards the back in saleroom to take in the scene. Admittedly, I see only the back of bidders, but, unlike in the movies, you really do have to make a pretty obvious gesture to catch the attention of the auctioneer. You’re not going to accidentally buy a Picasso by absent-mindedly tugging at your ear or scratching an itch. Salerooms are busy, and surprisingly noisy, places. People come and go freely; quite a few chat away about all sorts of things unrelated to the sale. The auctioneer is a combination of master of ceremonies and instigator and coaxer. Unlike a conductor, he has no score. He doesn’t know, for sure, how the sale will go, or from which direction the bids will come. He has to monitor the bidders in front of him, the bank of staff manning telephones to the side, and a screen, suspended from the ceiling, indicating online bids. And what has always captivated me about an auctioneer at work is that whereas a conductor keeps time, the auctioneer makes time. Time in a saleroom is surprisingly fluid and flexible and that was masterfully on display today with this online sale.

Today’s auction was sponsored by Bulgari. Sotheby’s staff in New York wore Bulgari jewelry. In the midst of bidding, the auctioneer drew attention to the glint of a jeweled bracelet on one staffer’s wrist, to glistening earrings, a stunning brooch, or an eye-catching neckless on another’s. He introduced the models to us by name and title. The staff making bids were called out too. Alex in London, by the by, was a year ahead of me at undergraduate. A fun fact I learnt, of no earthly relevance to the lots, is that there are two English Georges in the New York office. Thus the auctioneer made time, created moments in the seeming onward rush of bids for Sotheby’s staff to coax the bidder at the end of the telephone line to keep in the race. In this extra moment there’s still a chance, for that lucky final bid that will clinch it.

Adding to the drama, at least on my computer screen, was a clever engineer’s manipulation of windows. Salerooms came to the fore and were relegated in time with the bidding. New York outbids London. Here’s Asia jumps in. Two sale rooms are stacked, one over the other, as bids are batted back and forth. At times, it got as thrilling as Wimbledon or the New York Open. Tennis for a Tiepolo.

Sandro Botticelli (Italian,1445/5-1510), Portrait of a Young Man Holding a Roundel, n.d., tempera on poplar panel (23 by 15 ½ in.). Sotheby’s sale, New York, January 28, 2021, lot 15. Photo credit: Sotheby’s.com.

The sale of Sandro Botticelli’s Portrait of a Young Man Holding a Roundel, was breathtaking in the sums bandied about, but actually quite sedate in execution. Bidding started at $70M and increased at increments of $2M, topping out at $80M ($92.184,000 with commission). Even though it is extremely rare for such an archetypal example of early Renaissance portraiture to come on the market these days, there obviously aren’t too many collectors or institutions with the wherewithall to bid for one.

Much more exciting was to watch the bidding for one piece that started at $450,000 and reached $1.65M. With commissions, etc., it cost its new owner over $2M. Before the auction, Sotheby’s had posted an sale estimate of $700,000-$1M. The bidding for a small Dutch work, measuring 10 x 7 1/2 inches, began at $30,000 or so, breezed past the upper estimate of $90,000, and finally came to a breathless stop at $390,600, including commission. I’ll tell you what these two works were and why I was interested in them in Episode 2 of your must-read Hyde blog.

Rembrandt Harmensz. van Rijn (Dutch,1606 – 1669), Abraham and the Angels, 1646, oil on panel (6 ¼ by 8 ¼ in.). Sotheby’s sale, New York, January 28, 2021, lot 9. Photo credit, Sotheby’s.com.

One mystery I can’t explain is the unexpected withdrawal from the sale of its star lot, no 9, Abraham and the Angels by Rembrandt van Rijn, Sotheby’s had hyped it with a promotional tour around its international salerooms and online (https://www.sothebys.com/rembrandt). But oh-so discreetly, referring only to its lot number, the auctioneer announced at the start of the sale that number 9 had been withdrawn. More to come on that, I hope and expect. So, keep reading your Hyde blog!

1 note

·

View note

Text

Winslow Homer: Inspired by the Adirondacks

Recently, I heard a segment on NCPR about the Trout Lake artist Jeff Davis, who is in Florida during the pandemic lockdown. More accustomed to working in oils, he has taken up watercolors once again, a much trickier medium to manipulate and control. My mind immediately went to a pair of watercolors in The Hyde’s collection by an artist who also worked in both the Adirondacks and Florida: Winslow Homer (1836-1910).

One of the country’s greatest artists, Homer worked in a variety of media. On leaving school, he apprenticed for a commercial printer in Boston, making images for sheet music and commercials. During the Civil War, he became famous for his wood engravings published in Harper’s Weekly that illustrated accounts of the conflict. We have seen in a number of recent exhibitions at The Hyde that commercial and illustrative work was the prelude to careers for several American artists including John Sloan (1871-1951) and Dox Thrash (1893-1965).

Homer first visited the Adirondacks in 1870. He may have come in response to the run-away best selling travel book Adventures in the Wilderness; or, Camp-Life in the Adirondacks (1869) by William H. H. Murray. Residents of East Coast cities responded to the book’s call to the wild in droves. But there had also been a tradition among American artists, at least half a century old, of traveling through the region, capturing its natural beauty, and lauding its unspoilt wilderness as a national attribute. My predecessor as Hyde curator, Erin Coe, addressed the topic in her 2005 Hyde exhibition and its accompanying catalogue, Painting Lake George, 1774-1900.

Thomas Cole (American, born England, 1801-1848), View on Lake George, 1826, oil on wood panel (25 13/16 × 32 3/16 × 3 7/16 in.) Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth College: Purchased through a gift from Evelyn A. and William B. Jaffe, Class of 1964H, by exchange, 2017.11. © 2020 Trustees of Dartmouth College.

Winslow Homer (American, 1836-1910), Camping Out in the Adirondack Mountains, 1874, wood Engraving (9 11/16 x 15 1/2 in.) The Hyde Collection, Glens Falls, New York, Bequest of Charlotte P. Hyde, 1972.21. Photo credit: mclaughlinphoto.com.

Homer was a great outdoors man. He loved the comradery of camping trips. They are the subject of many of his prints and paintings, including Camping Out in the Adirondack Mountains (1874). Homer was also enamored of the lore around the year-round residents who acted as guides for city dwellers over the summer. Adirondack artist and author William James Stillman (1828-1901) described the guides as “rude men of the woods, rough and illiterate, but with all their physical faculties at a maximum acuteness, senses on the alert and keen as no townsman could comprehend.” They became heroic figures in the many books published about the region. Their principal characteristics were that they were extremely strong, dexterous with an axe, and able to build a lean-to within a few hours, or a hut in days. They were skilled at hunting, fishing, and tracking bear, cooking on an open fire, and story-telling around the campfire at night. Homer included Adirondack guides in many of his images of the region, including The Hyde’s little oil sketch of a commanding, statuesque figure executed during that first 1870 trip.

Winslow Homer (American, 1836 - 1910), Adirondack Guide, 1870, oil on canvas (8 1/2 x 13 1/2 x 1 1/4 in.) The Hyde Collection, Glens Falls, New York Anonymous Gift to The Hyde Collection, 1998.2. Photo credit: mclaughlinphoto.com.

On that occasion, Homer traveled in the company of fellow artist and keen angler Eliphalet Terry (1826-1896). They both produced fishing images on that trip. Angling was a major sport at the time and fishing images were popular. It was a passion that Homer shared with his brother Charles, and one that features in many of Homer’s paintings from the period, such as Crossing the Pasture (1872), in which two boys (Charles and the younger Winslow?) strike out across a field to go fishing.

Winslow Homer (American, 1836 - 1910), Crossing the Pasture, 1871, oil on canvas ( 26 1/4 X 38 in.) Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas, 1976.37. © Amon Carter Museum of American Art.

The adult brothers became members of the North Woods Club, famous for its fishing, near Minerva in the Keene Valley in 1888. Between 1889 and 1902, Homer produced a series of angling watercolors that brought him popular and critical acclaim. The Hyde possesses two of these.

Winslow Homer, (American, 1836 - 1910), A Good One, Adirondacks, 1889, watercolor (21 x 28 1/4 x 1 1/4 in.), The Hyde Collection, Glens Falls, New York, Gift of Charlotte Pruyn Hyde, 1971.68. Photo credit: mclaughlinphoto.com.

The first is A Good One, Adirondacks, painted in 1889. That year, he stayed at the club twice: for nine weeks in late spring and early summer; and for seven in the fall. The Hyde’s watercolor was presumably painted in the autumn, as there is a hint of golden foliage in a tree along the water’s edge while others are still in full deep-green leafage. We see a fisherman in a boat; a fish caught upon his line that is bend back on itself in a dramatic curve; and his free hand outstretched holding a net, ready to scoop up his prize. In early 1890, Homer sent thirty-three of these watercolors to his dealer, Gustave Reichard, in New York. He wrote the latter suggesting that he advertise the exhibition specifically to anglers. Homer recognized the appeal the images would have for aficionados of the sport, and he was right. A New York Times reviewer wrote, “It is his trout-fishing pieces…that are richest in color and done with the greatest pleasure.” Thirty works were sold, each for $125.

At the very time he was enjoying such commercial success in New York, Homer was on another angling expedition. This time, to Florida. The Hyde’s second watercolor dates to this trip. Winslow had first traveled to Florida four years earlier, encouraged by his uncle, Arthur Benson, who was himself an avid angler. The state was popular among fly fisherman for its inland waterways and abundance of sea trout, channel bass, mangrove snapper, and largemouth black bass. Homer stayed near Enterprise on the St. John’s River. The tropical setting, the Spanish moss hanging from the trees, and the light and color reflected in the water evidently captivated the artist as much as the sport itself.

Winslow Homer, (American, 1836 - 1910), St. Johns River, Florida, 1890, watercolor (23 1/2 x 28 3/4 x 1 in.) The Hyde Collection, Glens Falls, New York, Gift of Charlotte Pruyn Hyde, 1971.68. Photography by Joseph Levy.

There was a third place to which Homer traveled to fish: Quebec. He and his brother Charles owned a camp there. In many ways, Quebec provided the true call of the wild against which the Homer brothers could pitch their skills and manliness. The Adirondacks, for all the bravado of the guidebooks, was a wilderness tamed. It was a landscape largely denuded of its first growth forests; its mountains ravaged by ore mining and smelting; and its rivers depleted of native fish. Indeed, the North Woods Club had to stock the local rivers. Over the course of six weeks in the summer of 1891, Homer caught a total of six fish. It was in the untamed wilderness of Quebec that Homer could truly experience the thrill of landing a mature and wily native fish. He captured that excitement in his Canadian watercolors and conveyed it through the vigorous handling of the medium. Many depict men in canoes navigating turbulent waters. In these works, Nature is the more powerful and primal force, always on the verge of overturning anglers in their boats.

Winslow Homer (American, 1836-1910), Shooting the Rapids, 1902, watercolor over graphite on off-white, thick, moderately textured wove paper with watermark (13 15/16 x 21 13/16 in.) Brooklyn Museum, Museum Collection Fund and Special Subscription, 11.537 (Photo: Brooklyn Museum, 11.537_PS1.jpg).

In that The Hyde owns watercolors executed by Homer in two of the three locations at which he produced powerful images of a sport he loved—images invested with not only his love of that sport and with Nature herself, but also with an authenticity that appealed to contemporary collectors—you will not be surprised to learn that acquiring a Quebec watercolor is high on my wish list for future acquisitions. Please remember this post at Christmas!

0 notes

Text

Swiping Right

Before there was Tinder and the internet, there were artists and diplomats conveying images between potential suitors. There is nothing new in exchanging beguiling pictures.

Detail: Bartholomaeus (Barthel/Bartel) Bruyn, the Elder, (German, 1493 - 1555), Portrait of a Lady, ca. 1535, oil on panel (23 1/2 × 29 in.). The Hyde Collection, Glens Falls, New York, Bequest of Charlotte Pruyn Hyde, 1971.11. Photo credit: Joseph Levy.

It is possible that this portrait of a young woman by Barthel Bruyn the Elder (1493-1555) is just such a flirtatious, catch-me-while-I’m-free sort of picture. What tells me that? Firstly, she is not wearing a wedding ring. Secondly, her hair is in braids that escape her headdress. Well-to-do married women in sixteenth-century Germany covered their hair completely, only girls wore their hair loose, while virtuous, eligible maids wore their hair braided. That she comes from a prosperous family is evident from her clothing. The blouse beneath her velvet dress is embroidered with gold thread. Small pearls adorn a band in her headdress. The large sleeves are impractical. This young woman does not have to work.

She is in the market for a husband. It is possible that she has caught her man. The Metropolitan Museum possesses a portrait of a young woman by the same artist, presented in similar manner. She wears a dress and blouse of the same style; she holds a flower (a red carnation) in her right hand; her right index finger is adorned with a ring, but her left hand is bare. She, too, turns slightly to her right, but in this instance she turns towards her fiancé, who occupies a matching panel. Met curators believe the pair of portraits was commissioned to mark their engagement. We cannot know if there was a pendant, a boyfriend, to match The Hyde’s painting.

Barthel Bruyn the Elder (German, 1493–1555), Portrait of a Woman, 1533, oil on oak (12 x 8 7/8 in.). Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of James A. Moffett 2nd, 1962, 62.267.2

Barthel Bruyn the Elder (German, 1493–1555), Portrait of a Man, 1533, oil on oak (12 x 8 7/8 in.). Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of James A. Moffett 2nd, 1962, 62.267.1

Barthel de Bruyn was the society portraitist in Cologne, Germany. Then as now, the city was a great industrial and trading center. Politically, it was under the suzerainty of the Archbishop of Cologne, one of the electors of the Holy Roman Emperor. Its mercantile class was extremely wealthy and well-connected across Europe. The Hyde’s young lady is likely to have come from that class. Her family had her on the market for a successful and advantageous marriage.

Barthel de Bruyn played a little known part in the most famous story of Tinder matchmaking in the sixteenth century: Henry VIII’s misalliance with Anne of Cleves. After the death of his third queen, Jane Seymour, Henry was on the hunt for a new bride. Jane had provided him with his longed-for male heir, the future Edward VI, but it would be nice to have a male spare. The three choices on the international marriage market for a king considered a heretic in Catholic Europe were the sixteen-year old, Danish-born and recently widowed Christina, Duchess of Milan, or one of the daughters of the Duke of Cleves: Anne (twenty-four years old) or Amelia (twenty-two).

Henry sought diplomatic reports and portraits on all of them. Christina had no wish to marry Henry. The Cleves sisters were not so independent-of-mind. One would make the political alliance their brother negotiated. Henry’s ambassador, Christopher Mont, traveled to Düsseldorf, Germany to meet them. He reported back that “Everyman praiseth the beauty of the said Lady [Anne], as well for the face, as for the whole body, above all other ladies excellent.” The clincher may have been the comment, “She excelleth as far as the Duchess [of Milan], as the golden sun excelleth the silvern moon.” He returned to London with recent portraits of the two sisters by none other than Barthel de Bruyn. That of Amelia no longer survives, and that of Anne may be the panel painting preserved at St. John’s College, Oxford. A portrait of Anne by an artist in Barthel’s circle is kept at Trinity College, Cambridge.

Bartolomaeus Bruyn the Elder (German, 1493-1555), Anne of Cleves, oil on panel (50.2 x 36.8 cm). St John's College, University of Oxford, PP02. Photo credit: St John's College, University of Oxford.

Circle of Bartholomaeus Bruyn the Elder (German, 1493–1555), Anne of Cleves (1515–1557), ca. 1539, oil on panel (71 x 47 cm). Trinity College, University of Cambridge, Gift from Dr William Hepworth Thompson, TC Oils P 39. Photo credit: Trinity College, University of Cambridge.

Mont was unable to confirm the accuracy of Barthel’s portrait so Henry sent Hans Holbein the Younger to paint Anne himself. The portrait that caused all the trouble is now at the Louvre. With a few artistic tricks, Holbein airbrushed Anne’s flaws. By painting her face on, he reduced the prominence of her rather large nose, and he smoothed away the pockmarks caused by small pox that marred her face. Henry had fallen in love with the idea of Anne of Cleves. She was the right age for him, a man in his late forties. She was gentle and would obey. Holbein’s portrait showed she had a fine figure and regal bearing.

Hans Holbein the Younger (German, 1497-1543), Anne de Cleves, 1539, parchment on canvas (25½ x 18¾ in.) Musée du Louvre, Paris, France, INV. 1348. Wikimedia Commons.

But Henry fell out of love with her the minute he saw her. It was probably as much her lack of sophistication as her looks. Just after she landed in England, Henry appeared in disguise and unannounced. He wooed her in the manner of a courtly romance of old. Anne, embarrassed, perhaps not even understanding what he was saying, simply ignored him. The wedding went ahead for diplomatic reasons, but Henry quickly sued for divorce on the grounds that an engagement had been contracted years before between Anne and a French prince. It was a legal nonsense but a compliant English Church got Henry off the hook. Anyway, Anne and Henry became friends. She outlived him and his last two wives.

What’s interesting is to compare The Hyde painting with the others by Barthel. He had a formula. His figures stand in a shallow space against an undefined background with slight modeling of light and shadow. The woman turns to her right. And he takes particular care to portray the details of her costume.

The Hyde’s young maid maybe a woman on the hunt for a husband, or perhaps a fiancée looking forward to her wedding day. Whichever, modern-day snappers should beware. If the tale of a young woman from the sixteenth century is anything to go by, pre-marriage selfies may get you into trouble!

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Facetiming the Divine

This post is an experiment. Can our current use of online communications systems provide analogies for the way religious imagery worked on and for the viewer in the Middle Ages?

While we’re at home, we can find any number of YouTube videos to watch that are intended to be educational and instructive. I have participated in a number of live webinars and meetings but my direct participation is oftenmoderated in some way. I have to raise a hand or type a comment that may, or may not, be noticed by a moderator. Finally, there is the direct form of communication via Facetime or Zoom. Distance constricts and all participants are together, responding to each other in real time.

Anonymous, (Italian, 6th century) The Arrest of Christ, mosaic, S. Apollinare, Ravenna, Italy. Photo source: Web Gallery of Art.

When we first study medieval art history, we are shown the grand mosaic narrative cycles in S. Apollinare (before 526) and San Vitale (525-47) in Ravenna, Italy. The churches’ architecture asserted a continuation of the Christian Roman Empire, while their decorative schemes included narrative cycles, catechizing visualizations of doctrine, and imposing assertions of imperial authority through portraits of the Byzantine emperor and empress. As the two halves of the old Roman Empire diverged, Christendom split into the western Latin Church based in Rome and the eastern Orthodox Church centered on Constantinople. The two developed different approaches to religious art. The Orthodox Church restricted the creative license of artists. God, not man, was the sole creator. Thus, tradition and authority governed religious art, more so than in the West.

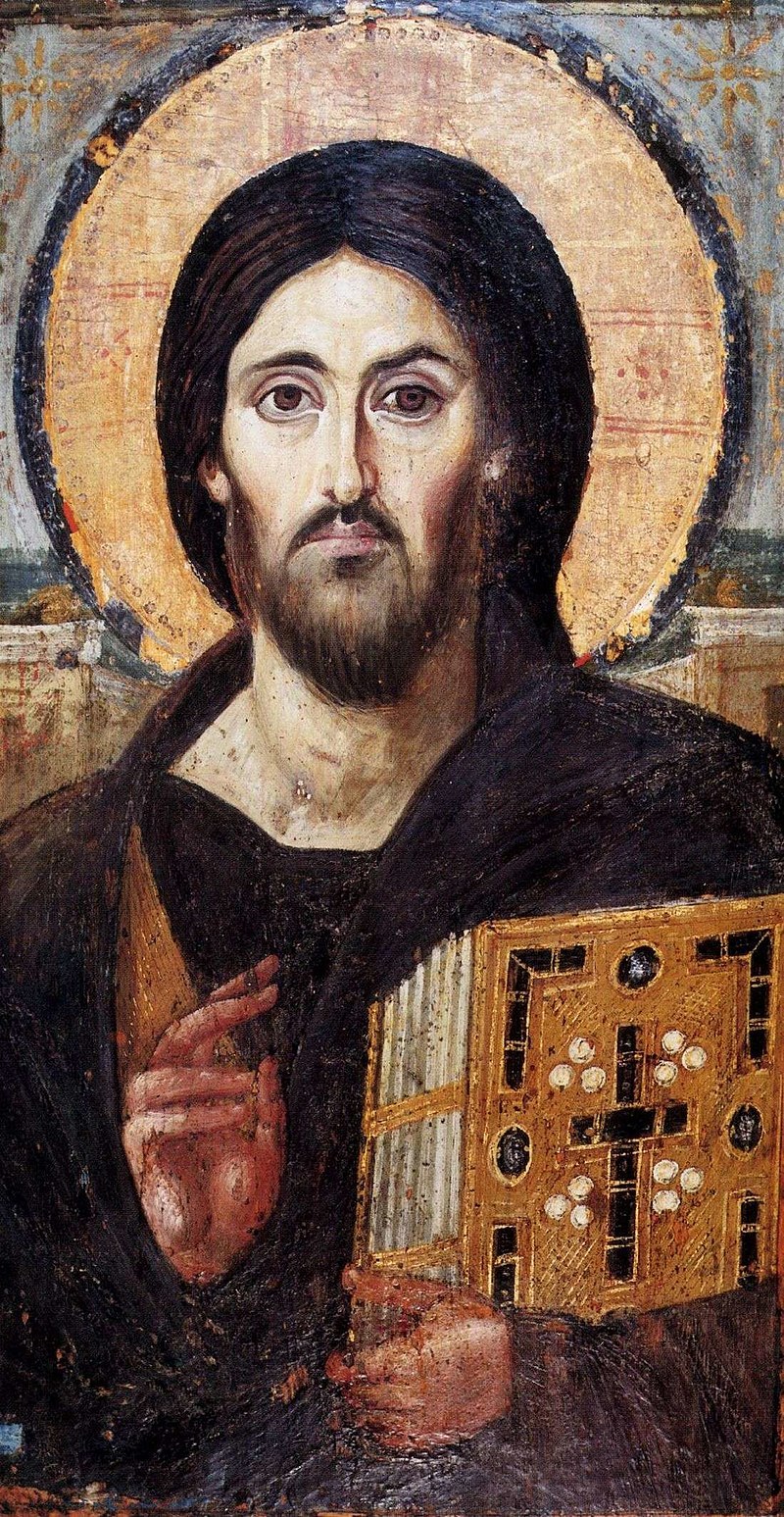

Anonymous (Egyptian), Christ Pantocrator, 6th century, encaustic on panel, Mount Sinai, Egypt. Photo source: Wikimedia Commons.

The East also developed the icon. Primarily a devotional image, it was invested with a unique power. When you stand or kneel before an icon in veneration of the sainted or divine figure portrayed, you are in their presence. Communication is direct. The icon is, in a sense, Facetime. While the style and imagery of icons did infiltrate the West, we are usually taught that the West did not adopt the notion that the icon give you direct access to the person or event depicted. And yet, there were images and occasions in the western tradition when distance and time collapsed and the devout was present at a sacred event or before a holy or divine person.

As Christians have just marked Easter, I will use Crucifixion imagery to explore the analogue and digital powers of medieval art. At one level, the image of the Crucifixion signifies the story of Christ’s death, whether it tells that story in great detail, narrating the Gospel accounts, or it summarizes the story in the symbol of the figure of Christ on the Cross. Through their choice of details, the artist can elicit strong devotional and emotional sentiments in the viewer. Through the introduction of symbols, the image can become a vehicle for the articulation and propagation of theology and doctrine. But in the Latin West, when incorporated into the performance of the liturgy, the activated image can elide time and space and bring one into the Divine presence.

Anonymous (Italian), Equestrian Crucifixion, ca. 1350, tempera and gold leaf on panel (29 7/8 x 14 1/8 x 1½ in.), The Hyde Collection, Glens Falls, New York, Bequest of Charlotte Pruyn Hyde, 1971.4. Photo credit: Steven Sloman.

Known as the Equestrian Crucifixion (ca. 1350) because many of the Roman military are on horseback, this small Gothic panel at The Hyde hews closely to St. John’s account of the Crucifixion. Christ, His head wreathed with a mocking crown of thorns, is nailed to a cross atop which in Latin initials is Pilate’s scornful notice Iesus Nazarenus Rex Iudicorum (Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews). His mother Mary is present, accompanied by three other Marys. St. John also stands at the foot of the cross. He is the only Gospel writer to claim to have been present at the event. Christ entrusted His mother into his care. Two of the soldiers have the Latin initials of the Roman state – SPQR for Senatus Populusque Romanum (“The Senate and People of Rome”)– emblazoned on their tunics. One knight holds the reed with a sponge soaked in vinegar that was offered to Christ; another the lance by which His side was pierced. With his hands together in prayer, this knight must be the centurion all Gospel accounts record was converted to Christianity. Later, in an apocryphal account, he was given the name Longinus; his lance is a precious relic venerated in St. Peter’s Rome.

The artist manipulates the viewer’s emotions. He enhances the pathos of the scene with the image of the Virgin Mary collapsing into the arms of the three Marys. Its gruesomeness was highlighted by the trails of vibrant red blood running from Christ’s wounds. Counselled by a priest or confessor in the more affective devotional practices of the fourteenth century, the devout onlooker would have responded to these visual cues. Encouraged to place themselves at the events, the believer would have felt the Virgin’s sorrow, endured the pain of crucifixion, and lamented the role their own sinfulness played in condemning Christ to His sacrifice.

In my analogy with modern communications, this is a powerful and affective narrative in HD, but it has not broken the bonds of time and space. The devotee remains in their sinful world and bound by earthly time.

Master of Monte Oliveto (Italian, active ca. 1305-1350), Crucifixion, ca. 1325, Tempera, gesso, gold leaf on panel (20½ x 18¾ in.), The Hyde Collection, Glens Falls, New York, Bequest of Charlotte Pruyn Hyde, 1971.5. Photo credit: Joseph Levy.

However, The Hyde’s Crucifixion Triptych (ca. 1325) had the power to break through between the earthly and heavenly spheres. The altarpiece was commissioned by a Dominican nun. We see her dressed in the Order’s distinctive black and white habit in the bottom left panel, kneeling before her patron saint, St. Romauld. She would have been well-versed in the kind of affective devotional practices taught by Dominican confessors to well-to-do women across Europe. She probably placed herself in the role of Mary Magdalen and imagined herself at the foot of the cross, her hair becoming matted with Christ’s blood as it trickled down the cross. Dominican nuns were known to translate such affective devotion into physical acts, such as fasting on the Host alone, as St. Catherine of Siena was to do within a few decades of this altarpiece’s creation.

Painted onto the wings are the nun’s patron saints, among them her fellow Dominicans, Dominic and Thomas Aquinas. Their portraits helped to focus her prayers, though there is no sense here that they behaved like icons, transporting her to their presence in heaven.

However, there is evidence that Dominicans felt that Christ could come to them through the Crucifixion image. Within the convent, Dominicans slept, studied, and prayed in individual cells, and they most commonly had an image of the Crucifixion with them, whether a painting or a sculpture. From written accounts, we know that such images were used to direct prayer, but they were also a consolation, evidence of Christ’s personal compassion for the Dominican’s life of prayer. In addition, there are stories of how Dominican while they slept felt the presence of the divine enter their cell through the image they were accustomed to prayer before. In my modern analogy, communication can work through the image both ways, but not simultaneously.

Bartolomeo Caporali (Italian, c. 1420–c. 1505), assisted by Giapeco Caporali (Italian, died 1478), Missal (detail), Crucifixion, 1469, Ink, tempera, silver and burnished gold on vellum ( 35 x 25 cm). The Cleveland Museum of Art, John L. Severance Fund 2006.154. ©The Cleveland Museum of Art.

There was one specific Crucifixion image that could operate as a direct form of communication between the mortal and the divine. It was the image of the Crucifixion that adorns the Canon of the Mass in a missal. Alas, The Hyde does not, yet, possess one of these. I take my example from a stunning missal in the collection of the Cleveland Museum of Art. The Caporali Missal is a lavishly illustrated Mass book executed for the Franciscan church of San Francesco in Montone, Italy (1469). The manuscript was used by the officiating priest at the altar during the Mass. It contained the words and prayers he had to recite. The principal illuminations were the work of Bartolomeo Caporali (ca. 1420-ca. 1505), including the Crucifixion scene that opens the section of the missal called the Canon of the Mass. These are the unchanging words at the heart of the service, when the mystery of transubstantiation takes place, and the bread and wine become, in part through the agency of the ordained priest, the body and blood of Christ. The priest who officiates thus looks upon an image of the Crucifixion as it occurs anew at the altar. The sacrifice is made afresh for the benefit of those present. In that moment of the mystery of the Mass are telescoped sacred and earthly time, the eternity of Heaven and the particular moments on earth of the historical Crucifixion, the priest’s celebration, and all performances of the Mass entrusted to the care of the universal Church.

There are two particularly important details to notice in this image. Firstly, an angle holds up a chalice to collect the blood from Christ’s side wound. This is a visual assertion of the doctrine of transubstantiation. Secondly, St. Francis, who kneels in Christ’s blood at the foot of the cross, shows the marks of the stigmata, a favor shown him for his great devotion. What friar using this missal cannot have prayed for a similar benediction?

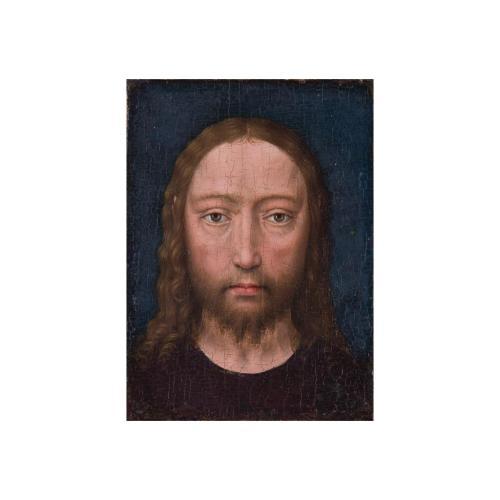

School of Hans Memling, (Flemish, ca. 1430-94), Head of Christ, ca. 1480, oil on panel, 4 13/16 x 3 9/16 in. The Hyde Collection, Glens Falls, New York, Bequest of Charlotte Pruyn Hyde, 1971.1.

A final image of Christ in the collection to consider is The Head of Christ (ca. 1480) attributed to the School of Hans Memling. In this small devotional panel painting, Christ stares directly out of the panel. There was such a desire to know the face of the Savior in fifteenth-century northern Europe that an official portrait was created, based upon a forged text known as the Letter of Lentulus. Purportedly a report sent to the Roman Senate about Christ, it described Him as having shoulder-length hair, parted in the middle, that was the color of “unripe hazelnut,” and a forked beard. Jan Van Eyck (1390-1441) first painted this image ca. 1438 and it was repeated by Dirk Bouts (1410/20-75), Hans Memling (ca. 1430-94), and their workshops throughout the remainder of the century.

This image was undoubtedly based upon the great images of Christ Pantocrator that looked down on believers from the domes and apses of Orthodox churches, and from the icons that derived from them. But as popular as these images were in northern Europe, and as immediate the sense of His presence is in them – his face up against the picture plane – they did not behave as icons. Their particular power in the Latin West lay in their use as indulgenced devotional imagery. An indulgence was a document issued by the Church that ensured the bearer time off their purgatorial sentence for their sins. By reciting a hymn such as Salve sancta facies (Oh Holy Face) or Ave facies praeclara (Hail, splendid face) before such an “authentic” portrait of Christ, one could more speedily pass through purgatory and enter Heaven. Here my analogy breaks down because the power of this type of popular image lay not in its facilitation of communication with the Divine, but with its ability to speed one’s entry into Heaven after death, there to reside for eternity in the very presence of God. Facetime and Zoom cannot take us to the other party just yet.

0 notes

Text

Christian Narrative Painting

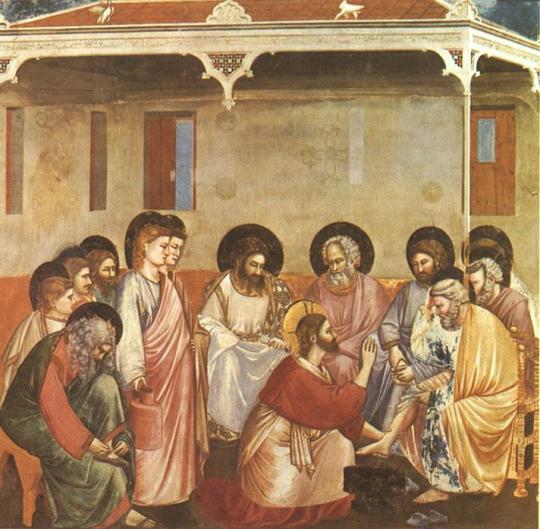

Those of you who took an Art History survey course undoubtedly learnt the name of Giotto. Between 1303 and 1306, he decorated the Arena Chapel in Padua, Italy with frescos that narrate the life of Christ. This artistic and architectural commission fulfilled the principal functions of religious art outlined in my previous posting. It provided a setting for the performance of the liturgy; it provided a visual education in the fundamental Christian narrative and tenants of the faith; and it was an expression of power, wealth, and status. The chapel was commissioned by Enrico Scrovegni (d.1336), a notable Paduan businessman whose wealth and status derived from money lending. Termed usury by the Church is was a tainted profession. Scrovegni sought to earn merit for his soul through this act of religious patronage as well as from the masses said for him and his family daily at the chapel’s altars. The beauty of the chapel’s decoration was as much a statement of his taste, wealth, and social status as it was a gift to God and the Virgin Mary, to whom the chapel was dedicated.

Giotto told the story of Holy Week, from Christ’s entry into Jerusalem on Palm Sunday to His appearance to Mary Magdalene following his resurrection on Easter Sunday, in twelve episodes. Giotto’s style was revolutionary. With simple, volumetric figures that convincingly occupied a definable space, he created dramatic tableaux that narrated the events clearly, concisely, and with great emotion.

Giotto (Italian, 1267-1337), The Last Supper, 1303-05, The Arena Chapel, Padua. Wikimedia Commons.

Two scenes mark the events liturgically commemorated on Maundy Thursday: Christ’s last supper with his disciples, and His washing of their feet. It is tradition in Britain on Maundy Thursday that the Queen distribute specially-minted maundy money, in lieu of washing feet, which her medieval forebears once piously did. The Pope still imitates Christ’s act of humility.

Giotto (Italian, 1267-1337), Christ Washing the Feet of His Disciples, 1303-05, fresco, The Arena Chapel, Padua. Wikimedia Commons.

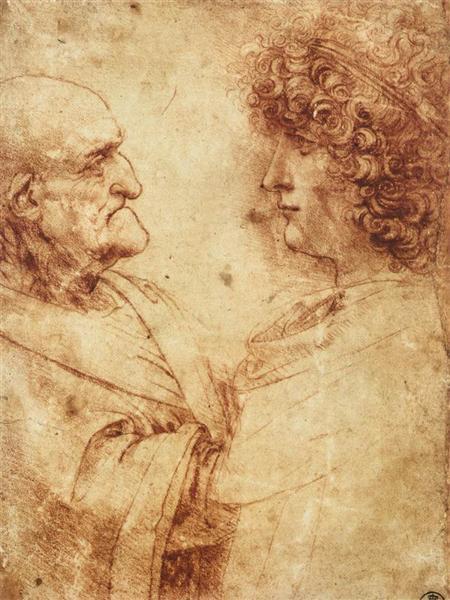

Leonardo da Vinci (Italian, 1452-1519), The Last Supper, 1495-98, fresco, Santa Maria delle Grazie, Milan. Wikimedia Commons.

Leonardo da Vinci’s Last Supper (1495-98), must be one of the most famous religious paintings ever created. The painting performs several functions. Firstly, it narrates the apostles’ reaction to Christ’s announcement that one of them will betray him. With Christ seated in the middle of a long refectory table, silhouetted against an open window surmounted by a semi-circular pediment (Leonardo’s subtle introduction of a halo), it places Christ dogmatically at the center of the Eucharist. And finally, as it was painted on the walls of the monks’ dining hall at the monastery of Santa Maria delle Grazie, Milan, it reminded the monks that they were Christ’s latter-day disciples. Their community meal was a meal in communion with Christ and his followers. [As a side note, The Hyde’s St. James the Less from the workshop of El Greco comes from a series depicting Christ and the twelve apostles originally commissioned for a Spanish monastic dining hall.]

Domenikos Theotokopoulos "El Greco,” (Greek, active in Italy and Spain, 1541-1614), St. James the Less, ca. 1595, oil on canvas, 34 5/8 × 30 in. The Hyde Collection, Glens Falls, New York, Gift of Charlotte Pruyn Hyde, 1971.18.

The most popular defense of religious art throughout the Middle Ages and Renaissance was that written by Pope Gregory the Great, ca. 600: “What writing (scriptura) does for the literate, a picture does for the illiterate looking at it, because the ignorant see in it what they ought to do; those who do not know letters read in it.” Pictures provided the clergy with the means of teaching an illiterate congregation Biblical stories, stories of the lives of the saints, and other essential truths. It was even possible to catechize the viewer and to convey doctrine through images.

As one walks through The Hyde, there are many examples of religious narrative art. Most have been excised both from their narrative sequence and context. Take, for instance, the jewel-like piece of twelfth-century stained glass that hangs in the main stairs of Hyde House. It depicts Christ’s presentation in the Temple. We can surmise that it was part of an Infancy cycle that depicted Christ’s birth.

Anonymous (French), Presentation of the Christ Child in the Temple, ca. 1195, stained glass ( 24 7/16 x 23 in.), The Hyde Collecction, Glens Falls, New York, Bequest of Charlotte Pruyn Hyde, 1971.112. Photo credit: Michael Fredericks.

In storage, there is a second stained glass panel removed from the cathedral of Saint-Ouen, Rouen, France that depicts Christ’s Entry into Jerusalem on Palm Sunday and presumably came from a window depicting His Passion.

Anonymous (French), Christ’s Entry into Jerusalem, ca. 1325, stained glass (20 1/16 x 13 5/8 in.), The Hyde Collection, Glens Falls, New York, Bequest of Charlotte Pruyn Hyde, 1971.114. Photo credit: Michael Fredericks.

Narrative sequences commonly filled the predella or base of an altarpiece. They were invariably related to the life of the saint honored in the altarpiece above. The dimensions of the Annunciation (ca. 1492) panel by Sandro Botticelli (1445-1510) in the Music Room suggest that it was part of a predella, presumably from an altarpiece dedicated either to the Virgin Mary or to Christ’s infancy.

Sandro Botticelli (Italian, 1444-1510), Annunciation, ca. 1492, tempera on panel, 11 1/2 × 15 1/4 in. The Hyde Collection, Glens Falls, New York, Gift of Charlotte Pruyn Hyde, 1971.10. Photo credit: Joseph Levy.

Across the room, the rectangular panel by Tintoretto depicting St. Helena Finding the True Cross is also a predella panel. The mother of the Roman emperor Constantine (272-337), St. Helena (ca. 248-328) was famous for her discovery of the buried cross upon which Christ was crucified, and for her founding of churches in the Holy Land, particularly those of the Nativity and Ascension.

(Jacopo Robusti) Tintoretto (Italian, 1518-1594), The Discovery of the True Cross, ca. 1560-1570, oil on canvas (12 1/2 in.) The Hyde Collection, Glens Falls, New York, Gift of Charlotte Pruyn Hyde, 1971.48. Photo credit: Steven Sloman.

The Dance of Salome (ca. 1480) by Matteo di Giovanni di Bartolo (1435-1495) is also a predella panel. It likely brought to a conclusion episodes from the life of St. John the Baptist.

Matteo di Giovanni di Bartolo, (Italian, ca. 1435-1495), The Dance of Salome, ca. 1480, tempera and gold leaf on wood panel (17 1/4 × 20 3/4 × 2 3/4 in.), The Hyde Collection, Glens Falls, New York, Gift of Charlotte Pruyn Hyde, 1971.28.

Matteo derived the scene’s composition from Donatello’s bronze font in the Baptistry in Siena (ca. 1427). The scene provided Donatello (1386-1466) with the opportunity to flaunt his ability to create the illusion of recession through the new technique of linear perspective. He created the image of three spaces, one behind the other, each connected through an open arcade. In each he set a different event. In the far distance, John’s head is carried from his cell by the executioner; in the middle room, musicians play; and in the foreground space, a servant presents Herod with the severed head.

Donatello (Italian, 1386-1466), Feast of Herod, 1423–1427, bronze, Battistero di San Giovanni, Siena, Italy. Photo credit: I. Sailko. Commons.wikimedia.org

Matteo simplified the arrangement. He kept the arcaded division of spaces but removed the figures from all but the foreground scene. Rather inexplicably, he introduced across the front plane of the panel free standing columns. While they complete the architecture of the banqueting room, they disrupt the narrative, which is undoubtedly why Donatello employed artistic license and omitted them. Matteo’s servant rushes forward on bended knee in the center of the panel, but his outstretched arms are obscured by a column and the platter with the saint’s decapitated head seemingly levitates on its own. Matteo allows the rational of the architectural setting he so proudly created to disrupt the visual denouement of his narrative.

Accurate to a fault with the architectural logic of his constructed space, Matteo, probably unintentionally, recorded a fact about Renaissance interiors that we might otherwise overlook. Large halls were used for multiples purposes. At mealtimes, tables were set up and removed shortly afterwards. It is clear that Herod’s dining table is a board on trestle legs. The table in Leonardo’s Last Supper is of similar construction. Tables, benches, and chairs were collapsible as we see in these instances.

It is debatable how visible predella panels were to the congregation, as it was often kept at some distance from an altar by choirstalls and screens. The predella rested upon the top of the altar. It functioned as a stand to elevate the altarpiece’s main panel above the heads of the officiants. Candlesticks, liturgical vessels like the chalice and paten, and the bodies of the officiants would have obstructed one’s view. Predella scenes were most clearly visible to the officiants. It is interesting to note with regard to this image that the Baptist’s beheading had long been interpreted by the Church as a precursor both to Christ’s execution and the presentation of the host on a paten during the Mass. With this particular scene, the priest looked upon an antecedent to his own actions.

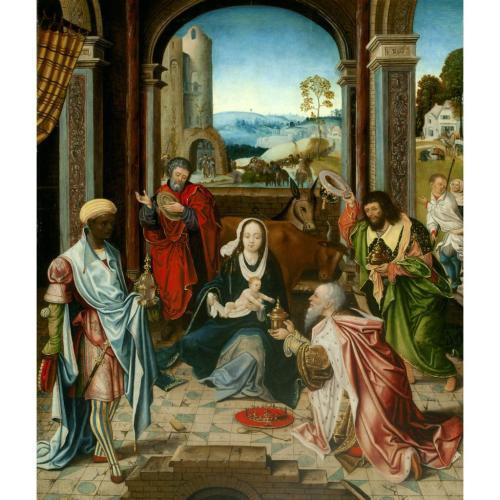

The most popular Biblical stories were frequently illustrated in a single scene rather than as part of a narrative sequence. The Adoration of the Magi was a very popular story throughout Europe during the Renaissance and Baroque. Artists gave free range to their imagines as th ey depicted eastern wise men in exotic clothing accompanied by strange animals and large entourages. Collectors enjoyed have such visually pleasing paintings to look at all year round. The Hyde’s example, painted by an unknown Mannerist artist in Antwerp is typical of the type commonly found in the homes of well-to-do merchants in that city.

Antwerp Mannerist, after Jan de Beer (Flemish, ca.1475-ca.1528), Adoration of the Magi, ca. 1520, oil on oak panel, 29 x 25 1/4 in. The Hyde Collection, Glens Falls, New York, Gift of Charlotte Pruyn Hyde, 1971.2.

An Old Testament story not so well know today hangs over the stairs in Hyde House. It is Paolo Veronese’s Rebecca at the Well (ca. 1570). According to the story in Genesis (24: 1-28), Abraham sent his servant to find a wife for his son Isaac. The servant asked God for a sign to indicate he had found the right woman. Rebecca gave it when the servant asked for water. In return, he gave her jewelry, which Veronese has her delightedly display on her wrist.

Paolo Caliari Veronese (Italian, 1528-1588), Rebecca at the Well, ca. 1570, oil on canvas (28 1/8 × 31 3/4 in.) The Hyde Collection, Glens Falls, New York, Gift of Charlotte Pruyn Hyde, 1971.57. Photo credit: Steven Sloman.

This painting was not part of a narrative cycle, but rather a stand-alone image. If it graced a home rather than a church, it was likely intended to instruct a young girl or wife in the virtue of accepting patriarchal authority. For in the Renaissance, Rebecca was a role model for the good wife. She was maidenly and accepted the choice of husband made for her. Described as “very fair to look upon,” artists took full advantage of the opportunity to paint beautiful young Rebeccas, blond and bedecked in bling.

Finally, the Crucifixion was undoubtedly the most frequently painted Biblical event. I shall examine the power of that imagery in a future post.

0 notes

Text

If not graven idols, what is Christian art?

For Christians, Sunday was Palm Sunday, the day they celebrate, and some even reenact, Christ’s entry into Jerusalem, when his supporters climbed the tress and strew his path with palm fronds.

Anonymous (French), Christ’s Entry into Jerusalem, ca. 1325, stained glass (20 1/16 x 13 5/8 in.), The Hyde Collecction, Glens Falls, New York, Bequest of Charlotte Pruyn Hyde, 1971.114. Photo credit: Michael Fredericks.

In the Middle Ages, when every church was perceived as a manifestation of the Heavenly Jerusalem, the church became a representation of the early city. Galleries were built over the west door for the choir to occupy as the clergy and laity processed in as Christ had once ridden into the holy city. At Wells Cathedral, a hidden gallery was constructed within the stone façade to accommodate the choir. The boys’ voices emerged through holes in the wall behind sculptures of angels.

Detail: West facade of Well Cathedral, 1220-48, Wells, Somerset, UK. Holes behind the quatrefoils filled with sculpture allowed the sound of the cathedral choir to resonate as one entered the cathedral’s west door on Palm Sunday. Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker, "Wells Cathedral," in Smarthistory, July 18, 2017, accessed April 6, 2020, https://smarthistory.org/wells-cathedral/.

This week, Holy Week, is the most important in the Christian calendar. On Maundy Thursday, the faithful will commemorate Christ’s last supper with his disciple, when He washed their feet, mourn His crucifixion on Good Friday, and celebrate His resurrection on Easter Sunday.

At the end of the Maundy Thursday service, priests in Catholic and Episcopalian churches will follow the centuries-old tradition of stripping the altars of their rich liturgical paraphernalia. They will carry away candlesticks, chalices, and crosses, and fold up richly embroidered altar cloths. Statues will be removed or covered. The church will be left bare. The sacrament will be removed from the high altar and placed in a temporary Easter Sepulcher, representing the removal of Christ’s body to Joseph of Arimathea’s tomb. I always find it striking to watch this ceremony. The congregation leaves the darkened, denuded church in silence.

It is a wonder, given the stricture against “graven idols” in the Ten Commandments, that Christian churches should have so much religious art and, indeed, such a rich cultural history of fine art, architecture, music, and the decorative arts. Once the Early Church started to accept Gentiles, particularly anyone who had grown up with the Greek and Roman pantheon of gods and statuary, it was something of a losing proposition to forbid all imagery. The fight was lost with the conversion of the Emperor Constantine in 315. He gave the Roman church silver statues of Christ and the apostles. Such cultural largesse was a standard form of imperial patronage and one the recently legalized Church was not in a position to refuse.

The Church developed several arguments for its use of and expenditure on art. Firstly, it needed to be able to perform the liturgy in a suitable building and with ritual implements. Secondly, as Pope Gregory argued in around 600, imagery helped to educate and catechize a largely illiterate congregation. The twelfth-century Abbot Suger of Saint-Denis, who in some sense was the creator of the Gothic style, wrote in his defense of the artistic riches of his abbey church that the beauty of the bejeweled liturgical vessels and the aura created by the brilliant stained glass helped to raise his thoughts from the mire and sin of this world towards the glory of heaven. In truth, he was also motivated to use art in the same manner as royalty and the aristocracy. He sought to instill awe in those who might otherwise challenge the Church’s position. It was necessary to ape the trappings of secular authority to advance and protect the Church’s own claim of independence and internationalism over and above the power of local rulers. As a divinely established institution, the glory of the Church reflected the majesty of God.

The chevet (ring of eastern chapels) at Saint-Denis, ca. 1140, Paris, France. © 2018 Richard Chenoweth.

The adoption of worldly trappings of authority is beautifully rendered in The Hyde Collection’s St. Peter Enthroned (ca. 1475-1500). Here Christ’s chosen head of the Church, the first pope is regally attired like a medieval monarch. He sits on a grand sculpted throne, swathed in a bejeweled cope of rich velvet and gold threads, wearing the papal triple tiara and holding the regalia of his office: the cross and the keys to the kingdoms of heaven and earth given to St. Peter by Christ Himself.

Unknown (Flemish or Portuguese, St. Peter Enthroned, ca. 1475-1500, oil on panel (12 1/4 × 8 1/2 in.) The Hyde Collection, Glens Falls, NY, Gift of Charlotte Pruyn Hyde, 1971.6.

There have been moments in the Church’s history when it has banned imagery. The Orthodox Church went through two periods of iconoclasm, the destruction of imagery, in the late eighth and early ninth centuries. Calvinists during the sixteenth-century Protestant Reformation whitewashed church interiors. English Puritans decapitated sculptures and smashed stained before boarding ships and sailing for the New World where they built their stark, unadorned meetinghouses.

The Catholic Church enthusiastically reasserted the power of religious art in the Baroque period. Shaken by the Protestant Reformation, it reclaimed its authority and rebuilt itself, constructing massive, richly adorned churches. The princes of the Church were as magnificent as any lord or princeling, the Pope as any monarch. We see redecoration of churches The Hyde Interior of a Gothic Church after Pieter Neeffs the Elder (1625-50). The side altars are dressed in altar cloths and adorned with tall winged Baroque altarpieces. At the far east end of the church, through the arch of a rood screen that divided the world of the clergy from that of the laity, one can discern a high altar, bedecked with candlesticks and a colorful altarpiece.

After Pieter Neeffs the Elder, (Flemish, ca. 1578 - 1659), Interior of a Gothic Church, ca. 1625 - 1650, oil on panel (13 × 11 3/4 in.) The Hyde Collection, Glens Falls, NY, Gift of Charlotte Pruyn Hyde, 1971.31.

In its day, the painting would have been viewed as a confessional declaration. Protestants in the newly independent Dutch republic possessed paintings of their whitewashed church interiors. In this painting by Pieter Saenredam ( 1597-1665), the Calvinist emphasis on the spoken word over the liturgy performed at an altar is manifested in the prominent pulpit positioned halfway down the left side of the church.

Pieter Jansz. Saenredam (Dutch 1597-1665), The Interior of St Bavo's Church, Haarlem (the 'Grote Kerk'), 1648, oil on panel (174.8 x W 143.6 cm), National Galleries of Scotland, Scottish National Gallery, NG 2413, Photo credit: National Galleries of Scotland

The Hydes were Presbyterian. Charlotte Pruyn’s family were descendants of Dutch Calvinists. I have always thought that a certain Reformist modesty regulated their lives and collecting. It did not affect the quality of their collection, rather it manifested itself in the scale and tone of what they collected. Hyde House is unique in its design but not ostentatious in scale or decoration. The Rembrandt is the largest painting the Hydes ever bought. In collecting religious imagery, they avoided large altarpieces, gruesome martyrdoms, and Baroque saints in ecstasy. Neither did they buy grand eighteenth-century portraits alluding to an Old World aristocratic heritage.

As patrons of religious architecture, they were governed by an elegant restraint. We see this in their patronage of Ralph Adam Cram (1863-1942) architect of the First Presbyterian Church (1927) in Glens Falls. Cram was the leading American Gothic Revival architect of the early twentieth century, the architect of New York’s Riverside Presbyterian Church. The Hydes’ archive contains many letters to Cram concerning design and decoration. They traveled into the Midwest and through New England to visit and review other churches, garner ideas, and assess the work of craftsmen. The restraint in the architectural decoration at First Presbyterian is reminiscent of that of the Cistercian movement, founded in response to the lavish decoration of Benedictine monasteries like Saint-Denis. St Bernard of Clairvaux (1090-1153), the founder of the Cistercian order, argued that for monks who were devoted to the study of the Bible, narrative cycles, whether painted on walls or glass, were an unnecessary and indeed dangerous distraction. Direct access to scripture negated the need for religious art.

Ralph Adam Cram (American, 1863-1942), First Presbyterian Church, 1927, Glens Falls, New York.

For the Hydes as collectors, religious art exemplified styles and movements within the history of Western art. They largely overlooked its religious function and meaning. Yet the art was never intended simply to be pretty. Its raison d’être lay in its liturgical role, what it taught, or the power it projected. I will examine these roles in further postings this Holy Week.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Are We Living In An Edward Hopper Painting?

I read two articles this week that asked that question. And so I ask, do you think Edward Hooper is the most apposite artist for this extraordinary moment?

I must admit that I have been thinking of Hopper recently. The other night, I looked out my window at the pools of light in a neighboring lot and immediately thought of Night Shadows.

Edward Hopper (American, 1882-1967), Night Shadows, 1921, etching, 7 × 8 1/2 in. The Hyde Collection, Glens Falls, NY, Purchased with funds from the Waldo T. and Ruth S. Ross Charitable Trust, Glens Falls, NY, 2017.1

In this Hopper print from 1921, the viewer looks down from a high vantage point on a solitary man walking into a cone of light along a deserted street. He passes a shuttered café. Over the four years I have looked out my window, I realized that, until we recently shuttered the restaurants and postponed public entertainment, even in quiet downtown Glens Falls I would see someone cutting across the lot. But not for the last week or so.

I have always thought that the Hiram Krum House (built in 1860 on the corner of Warren Street and Oakland Avenue) is the most Hopperesque house in town. And yet to, as the traffic on Warren Street dwindles to a trickle and Bates-motel quiet settles over it, it seems no more austere a presence than before.

The Hiram Krum House, 1861, Glens Falls, NY.

And so, I wasn’t quite ready to agree with Jonathan Jones in his Guardian article entitled “We are all Edward Hopper paintings now.” Jones argues that “the fabric of modern cities and landscapes is for [Hooper] a machine that churns out solitude.” He concludes his piece with the question: “when the freedoms of modern life are removed, what’s left but loneliness?”

To illustrate his point, Jones cites Nighthawks (1942), a painting in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago. Sarah Kelly Oehler, the Institute’s Field-McCormick Chair and Curator of American Art, recently blogged about this painting, finding in it a message of hope.

Edward Hopper (American, 1882-1967), Nighthawks, 1942, oil on canvas, 33 1/8 × 60 in. The Art Institute of Chicago, Friends of American Art Collection, 1942.51. Photograph: Alamy.

Indeed, she questions whether it is really the icon of “loneliness and alienation” we have long believed it to be. Painted in 1942, when New York City experienced wartime blackouts, she proffers the brightly lit diner as a welcoming beacon that may, in fact, be drawing the viewer in. When I look inside, I think I see the couple’s fingers touching on the countertop, and the server responding to one of his customers. If I were to enter, I am not so sure I would find “alienated, atomised individuals” in the words of Jonathan Jones. By joining in, I might enjoy a fleeting connection with others out late at night.

For Oehler, the fact that I can see one thing and Jones another in the art of Hopper creates connection, or at least the opportunity for connection, discuss, and community. Every artist, even a painter of loneliness, intends to connect with the viewer. That is the great social benefit of art.

If the loneliness of social distancing is wearing you down, find community through art at The Hyde Collection. Connect with us via Facebook, Instagram or the comments page of our website. Leave a message on our voicemail (518-792-1761). There’s no reason for Glens Falls to be Hopper-on-the-Hudson.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

A closing aside: As The Hyde was considering bidding for Night Shadows at auction in 2017, I went to New York City to inspect the print. I compared it with other copies held by the Whitney Museum of American Art. They also possess Hopper’s original copper plate. As I inspected it with a magnifying glass, I noticed that Hopper had made a common mistake. He had forgotten that a print is the mirror-image of what is incised on the plate. Any letters, if they are to be legible in the print, must be written backwards on the plate. Originally, he intended the word CAFE to be inscribed on one of the dark street-level windows. But he wrote the words the wrong way round. To mask his error, he deepened the shading in the window.

1 note

·

View note

Text

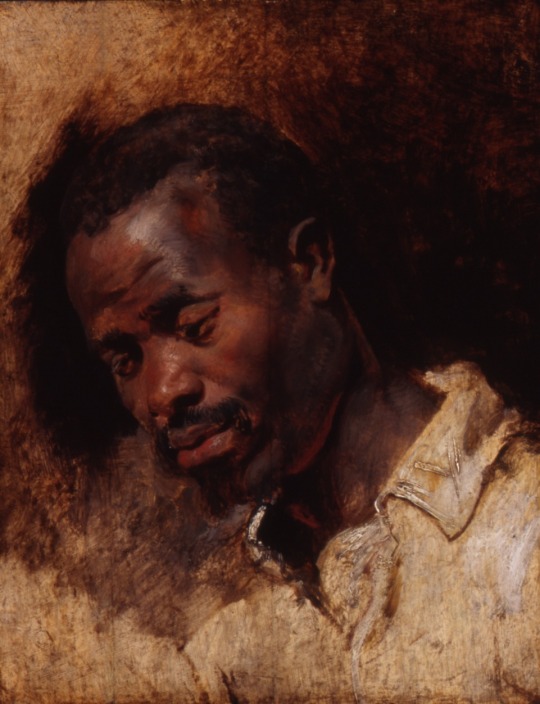

Here. The Black Presence in Western Art

This month, the Rembrandt Museum in Amsterdam opened a new exhibition entitled HERE. BLACK IN REMBRANDT’S TIME. The exhibition overlaps with The Hyde Collection’s presentation of the art of an accomplished, but little known, African American artist, Dox Thrash (1893-1965): DOX THRASH, BLACK LIFFE AND THE CARBORUNDUM MEZZOTINT. The Thrash exhibition is the first of three successive winter shows at The Hyde that will highlight African American art.

Dox Thrash (American, 1893–1965), The Champ, c. 1937–39, aquatint, private collection

I began this series with Dox Thrash, in part, because, as an artist, he fits neatly into the styles and history of western art that we know so well at The Hyde. He trained at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in the western tradition. Henry Ossawa Tanner (1859-1937), whose portrait by Thomas Eakins graces the main stairs in Hyde House, was an inspiration to Thrash. Indeed, he may have met Tanner in France following the end of World War I, in which Thrash served and was wounded.

Thomas Eakins, (American, 1844-1916), Portrait of Henry O. Tanner, ca. 1897, oil on canvas, 29 5/8 x 26 x 2 1/4 in. The Hyde Collection, Glens Falls, NY. Gift of Charlotte Pruyn Hyde, 1971.16.

Inspired by the Harlem Renaissance, Thrash was driven to make black life - his childhood experiences in rural George, his time on the road “ho-boing” (to use his term) as a vaudeville performer, and his professional life as an leading citizen of the black community in Philadelphia - the subject of art. Almost alone among African American artists of his day, Thrash appropriated the European tradition of the reclining female nude for the black female body. We see this most assertively in Thrash’s print Siesta (ca 1944-48), which was inspired by John Vanderlyn’s infamous painting, Ariadne Asleep on the Island of Naxos (1809–14). Vanderlyn’s painting, although clearly within the European tradition established in the Renaissance by such a master as Titian - think of his Venus of Urbino (1538) at the Uffizi Gallery - scandalized Protestant ,and particularly Quaker, Philadelphia. Thrash’s reclining nude is proudly African American. Images of the black female nude had long be problematic in American art and society because of the country’s history of abusing enslaved women.

Detail: Dox Thrash, (American, 1893–1965), Siesta, ca. 1944–48, carborundum mezzotint, on loan from Dolan/Maxwell

John Vanderlyn (American, 1776-1852), Ariadne Asleep on the Island of Naxos, 1809–14, oil on canvas, 68½ x 87 in. Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, 1809–14. © Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts.