Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Kaitlin Jencso: Disenchanted

Kaitlin Jencso is a photographer who lives and works in Washington, DC. Jencso explores the emotional terrain of ever-expanding and evolving relationships through loss, ephemera, bloodlines, and the land. Jencso graduated with a BFA from the Corcoran College of Art + Design in 2012. She won Best Fine Art Series at FotoWeek DC in both 2014 and 2016 and received the Award of Merit in the 2014 Focal Point show at the Maryland Federation of Art.

https://www.kaitlinjencso.com/

What challenges did you face in creating a long-term project that spanned over four years?

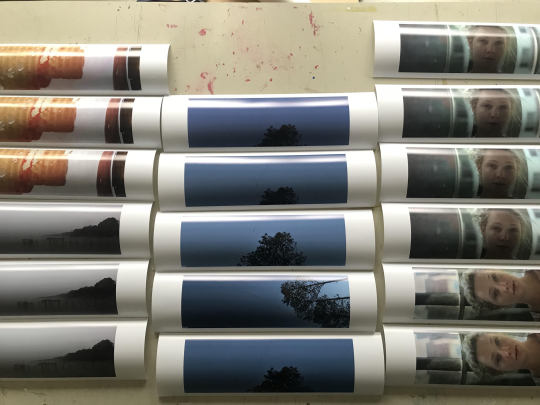

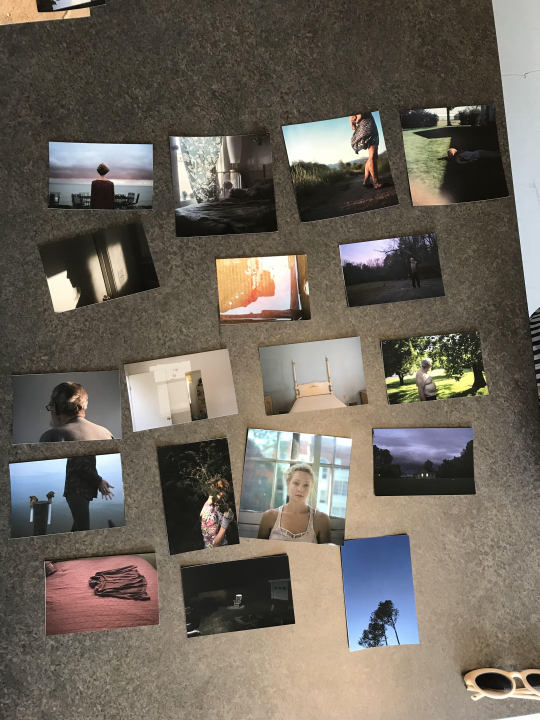

The main challenges I experienced while undertaking this long-term project was selecting an edit because of the large archive I had accumulated. I was shooting constantly on whatever camera I happened to have at hand at the time, so I was producing hundreds of images a month. All of these certainly didn’t make the cut, but it made for a glut of imagery to process.

The other most challenging part of doing this type of long-term work was dealing with repetition. Much of the imagery produced was taken at my parent’s home over the years, so there was a lot of recurring locations, rooms, and people. The variables were the poses, events, light, distance from the camera, and gestures. There were so many beautiful moments that were similar over the years that made for some tough editing decisions.

Did you find there was an opposition or dichotomy between, as you state, “the immediacy of the need to capture the moment as it unfolded” and the long-term nature of the work?

I think these things went hand-in-hand. The immediacy of the work stemmed from using the camera to capture an event as it occurred or a fleeting moment or feeling. I found that even when I wasn’t in the hospital room, or with a grieving family member, the weight of loss was upon me and tinting how I viewed my everyday experiences. I decided to photograph whatever triggered those feelings.

This allowed me to feel like I was doing something instead of idly standing by. I would review my image choices weekly/monthly and it became clear that this was a space for me to dwell in and process the experience. Because I was not interested in reporting events as they happened, but rather capturing fleeting feelings to convey the overall arc of grief, this became a long-term project with no distinct narrative.

Was it difficult to embody the role of voyeur within your own family? Did you feel removed or closer to them by capturing them through your lens?

I am the youngest of four children and have always been an observer of my family. As a child I would tuck myself into the corner of a room and just watch everyone around me. As I got into photography in my teens it felt only natural to continue this type of observation of those I was closest to, but this time through the lens. I have made work about my parents for various projects while pursuing my BFA, including my thesis work 20161, so they were accustomed to me following them with a camera. It never occurred to me to not document my family during this time. Although we were all grieving this loss in our own ways independently, we were also bound together by it.

During the actual act of photographing I was aware that I was using my camera as a barrier to acknowledging the reality of the situation and graveness of emotion. This was both a coping mechanism and a reflexive instinct. I’ve always believed art should be personal and authentic, and photographing these difficult times allowed me to process through a visual, emotive diary while also bringing me closer to my family by actively seeing and realizing their experiences.

How did you find beauty in painful and deeply personal topics?

I believe that there is beauty in the mundane. There is a captivating moment to be had in any scenario if you’re open to seeing it. I’ve trained myself to look for these scenes—magical light, a brief gesture, a small detail – that goes beyond recording reality to relaying an experience.

I follow this same mode of photographing when dealing with deeply personal or painful experiences. I harness the intensity of a feeling and distill it into a visually captivating and emotionally poignant image. The rawness and closeness push me to create images that are fiercely personal to me but convey an atmosphere that the viewer can also identify and empathize with.

What is next for you, will you continue working on this same series or are you embarking onto a new project?

I will always continue to photograph my family but am putting a period on Disenchanted. My goals are to take my final edit of 50+ images I have for this body of work and create a book within the next year. I am currently working on a new body of work which will be shown at the Hamiltonian gallery in April 2019.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Andrea Limauro: Mare Nostrvm

Andrea is an artist and city planner born in Rome, Italy and based in Silver Spring, MD, just outside Washington, DC. Andrea’s work explores issues of migration and identity, the fleeting concepts of home and safety, nationalistic narratives, and gun violence in the US. His work has been exhibited in galleries throughout the DC metropolitan region including IA&A at Hillyer, Touchstone Gallery, the Annapolis Maritime Museum, and the Arlington Art Center. His paintings have been featured in publications in the US, UK, and Italy. Andrea is a Board Member of the non-profit art advocacy Washington Project for the Arts.

http://www.andrealimauro.com/

Your work engages with the fleeting idea of home and safety in our world. How do you, as someone who has lived in many countries, define home?

My life experience is central to my understanding of “home.” My first experience with migration started early when I was 11 and my family moved to Belgium. I was in middle school – a terrible age for anything, let alone moving to a country where you do not speak the language. In Belgium I was faced with intense discrimination by some teachers. The south of Belgium had experienced mass migration from Italy a few decades earlier and anti-Italian sentiment was still very strong among some people when we arrived there in the 1980′s. I had a physics professor who would call me names - like dirty or stinky Italian - in front of my Belgian classmates and kick me out of the class for no apparent reason other than my background. My parents did not speak French, so I often helped them with grocery shopping and communication in public. I remember this one time when my mom sent me to a bakery while she and my father waited outside in their car. When I was inside the owner refused to sell me bread because of my accent. I was very upset and could not believe someone would act like that towards a child. When I went back to the car I told my parents that there was no bread left, rather than let them know about the episode for fear that my father would confront the baker. My experience in Belgium was very formative for the way I came to understand identity and discrimination. The cruel irony is that when we finally moved back to Italy we relocated to the north of the country where my southern Italian accent often got me singled out or excluded in high school and sports, teaching me yet another lesson about home and identity. I think that was the turning point for me was where I came to conclude that “home” for me would be a fluid concept, or something I had and could build in a place of my choice. It was kind of liberating and since then I have lived over half of my life outside my native country, and in half a dozen countries on three continents. Today, home is where I have my deepest sentimental relationships: Verona and Washington, DC.

Tell us about the inspiration and evolution of this series. What discussions do you hope for Mare Nostrvm to evoke?

Politically, the inspiration for “Mare Nostrvm” started as a reaction to all my current and past “homes” being affected by the global populist movement. It started with Brexit which affected me deeply as it would preclude me today, or my children in the future, to have the same wonderful experience I had in the 1990′s when I lived in England as a student. After that, Trump’s electoral victory on an anti-immigrant wave made me feel very unsafe in the US and forced my wife and I to have serious conversations about relocating. The final straw was the election of a right-wing populist government in Italy fueled mostly by anti-immigrant sentiments.

Artistically, while the political world around me seemed to go crazy, I could not stop thinking about the powerful images of women, children, and men packed on rickety boats trying to get to Italy. I was inspired by their bravery and desperation, leading them to make such a dangerous trip (the deadliest migration route in the world). I felt I wanted to do something about their humanity which often gets lost when right-wing politicians talk about them only focusing on the economic cost of hosting them, or worse, talk about them as being dangerous invaders. The geographic route of their migration and the language politicians use to describe it brought up a lot of parallels with Roman and Italian history. I started researching in more depth the Punic Wars and Italian colonial history to find inspiration for my series. I really started seeing everything as part of this 2000 years of history that links Italy with north Africa and the rest of the Mediterranean. Italy is very much the product of cyclical exchanges with our neighbors on the sea as much as our European neighbors to the north.

Your color palettes and materials are bright, and elicit a sense of happiness at first viewing—there are vibrant hues and a shimmering use of gold—can you tell us more about your use of color, especially in depicting such difficult topics?

I like to make art that is aesthetically pleasing, and the sea is my element. I love how beautiful the Mediterranean is, but also how it can make you feel small and how you must respect its power. I needed to make the sea beautiful and menacing at the same time. Therefore, the color choices are very intentional. The sea in all its depth is dark and grey whereas only its visible top layer shines with enticing and deceiving colors. I also wanted to use colors that connected the series to the story and aesthetics of ancient Rome. From the patterns of cobblestone streets, to the gold leaves, to the reds and greens of Romano frescoes, it all comes back to my youth growing up in the “Eternal City.”

What do you feel will be the next step for this series of work?

I would love to expand the series and the sculptural aspect of “Mare Nostrvm” and find ways to bring it to Italy and Europe as I feel it needs to be seen there. The reception in Washington has been fantastic with great reviews in the Washington Post and the Washington City Paper, however, the theme of “Mare Nostrvm” is perhaps too far removed from the US, even though there are clear parallels with the migration debate in this country.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

RICHard SMOLinski: Scrutinearsighted

The unusual appearance of my printed name was developed to assist in pronunciation and to distinguish myself from the American children’s book illustrator with whom I share my name. By contrast, I am a Canadian artist interested in the ways that power structures influence and shape our realities and behaviours. I currently reside in East York, Ontario but for many years I lived in Calgary, Alberta. My work in the areas of drawing, painting, installation, bookarts and performance has been exhibited, presented and performed at public and university galleries, artist-run centres, alternate venues and festivals across Canada, the USA and the UK. I have also received major project grants from the Canada Council for the Arts and the Alberta Foundation for the Arts. I earned the first PhD in Art granted by the University of Calgary’s Department of Art for my combined creative and scholarly research project, Practices of Fluid Authority: Participatory Art and Creative Audience Engagement. A fellowship from the Canada’s Social Science and Humanities Research Council supported my doctoral research. In addition to my work as an artist, I am also an educator and have taught at the University of Calgary, Brock University and The Alberta College of Art & Design; currently I am an instructor at the Ontario College of Art & Design.

https://richardsmolinski.com/

How does being an educator inform your artistic practice?

I think I learn a lot from students, sometimes it is just finding out about a new artist that I am not aware of, and getting the chance to see a new way of thinking with art, but it can also be a reminder of how important “art” is. Often, though, I benefit from the passion of students; the way they care about things and ant to make a positive impact, reminds me of why I think art is worthwhile and important, and confirms my own desires to make a positive impact.

Your work often engages in wordplay and pairing terms together—does your process begin with writing and then move to visual?

Language and wordplay weaves throughout my process. Often I do start (or think) through devising coinages and puns, and these suggest possible images and relationships that are then more consciously developed. Other times, my working process begins with figurative gestures and poses that suggest different types of power dynamics and interpersonal relationships—as such image start to solidify, they might then suggest “textual” possibilities—like coinages and puns—that are subsequently incorporated into the work.

How does your work embody a sense of humor while also remaining keenly critical?

I think the humor is a defense mechanism, a way of not being crushed by how awful some situations are. It is a way of switching my perspective from being overwhelmed by the effects of power, to responding to source of the problem—those in power and the ways that they behave. Humor is my position on the power continuum; rather than using my creative energies to create mayhem and harm and exploit others, I try to use my creative energies as a positive force that points out the foolishness, greed and cruelty of those in power. I think that humor is a form of power and I take humor seriously, while it can be malicious and hurtful, I aim my efforts at making critical “fun” of those actions and individuals that are hurting others.

Can you describe the process of installing your work? Do you have a set way of showing these pieces or do you find that it changes and evolves over time or is dependent upon where they are shown?

Installing the work is like putting together a puzzle when you do not know what the final outcome looks like. I do not have a set way of showing the pieces, and for this installation I had prepared a number of new components that were predominately irregularly shaped, so the work was going to be quite different from its past installation.

Although there are a number of pieces that seem to go “well” together and have particularly strong relationships (and that I did plan to install adjacently), there were times in the installation that other possibilities and necessities were more important, and that my initial plans/assumptions changed. The Hillyer space was challenging because of the short wall with the pair of corners, the electrical conduit in one other corner and the variance in ceiling height. The narrative tableaux had to respond to these physical attributes and the final installation was much different than I planned. Especially different was the verticality of this installation. I anticipated a more horizontal flow, but the works’ spikes and troughs ended up being quite drastic—something that seems appropriate for the works’ chaotic sense of action and consequence—like being on a sociopolitical rollercoaster.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tender Bits: Rex Delafkaran

Rex (Alexandra) Delafkaran is a San Francisco, California transplant living and engaging as an interdisciplinary artist and dancer, curator and administrator in Washington, DC, working out of Red Dirt Studios. A San Francisco Art Institute alum, Rex has worked and exhibited in many galleries including the Smithsonian Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden. She is currently a participating guest writer at local online art writing publication DIRT, and curating projects of her own.

www.rexdelafkaran.com

How does your involvement in performance art affect your creation of visual arts, and vice versa?

My practice has come to teach me that they both must coexist. I have danced and moved creatively my whole life, and that I think directly affects all the art I make and the way my ideas manifest. What does the piece feel like to make, hold, move; how do these ideas and this research manifest physically in the world, in my body? The two practices flow in and through each other dynamically. It’s actually a really sweet experience to realize “oh ohh this isn’t supposed to be a sculpture, its a performance!”

How did you come to focus on language and identity as a theme throughout your works and across mediums?

After having moved across the country from California to DC, I began studying Farsi. I started attempting to write in partial English and Farsi as a practice, which was unexpectedly thrilling, and those began transforming into movement scores, which then became performances. Those elements of text then made their way into the ceramic sculptures I was working on, taking the notions of physical utility and intimacy and relating them directly to language. It kinda blew my mind, how much it all was coming together. Then in 2016 when the first iteration of the Muslim ban came to surface, the anger and disappointment and confusion I felt in response was completely overwhelming. Ultimately, I think it was a noticeable catalyst in this direction of my work. I began researching the history of Iran and the areas where my family is from, and began looking for more information about the relationship between the US and Iran, ancient Iranian art and cultural practices that appear in both places. Language is the intermediary in this process of questioning the relationship between my sexuality, cultural background, familial history, and hyphen American identity, and the relationship those have to my immediate and extended community. I’m in an excavation of sorts, a dig, and I am standing on the edge of a large pit with a pile of dirt next to me and clay under my nails.

You mention seeking out means of starting conversations and provoking thought with your works. What kind of conversations do you wish to initiate with this installation?

I think the extremely engaging and powerful aspect of working in conceptual art is that while I have been circling in my own little world about the work and its connections to art and culture and reality, there is room for so much dialogue. I want people to tell me how they feel about it—what do all these symbols do together? Do the chains feel violent to you? What is your relationship to flags? How do you feel about ceramic phalluses strapped to cinder blocks?

You recently participated in a cultural exchange trip supported by the Sister Cities program. What were your goals for the trip? Did you accomplish your goals? Of these, was there anything in particular you would have liked more time to continue pursuing?

The Sister Cities program was an incredible experience for me as person and as an artist. Going into the trip I was the most excited to film performances in historic areas in response to their architecture, and I really feel like I was able to get some exciting documentation from those moments. What I was surprised by was how moving the historically charged architecture and public spaces were. At the end I found myself wanting to make more site-specific, longer movement explorations. We also saw so many artists’ studios, I was surprised as to how inspired I was to make more sculpture when I got back to the US. The incredible attention to history and craft was impactful and certainly affected my perspective on what it can mean to be an “artist” in other parts of the world.

What aspects of your own cultural experiences and their impact on your work were you most excited to share with your counterparts in Rome?

It was so exciting and fruitful to share my experience as a queer Iranian American person with some of the artists we met. They expressed a lot of curiosity about why my identity felt like such a site for investigation for me, and that made me pay particular attention to who each artist is, what their relationship is to Rome culturally and socioeconomically. I wish I had more time to get an understanding of their relationship to the middle east and Islam actually, especially based on their government’s stance on refugee asylum and immigration. Seeing how other people work was so eye opening, the experience makes me want to talk more and collaborate with international artists absolutely.

What, if anything, surprised you most about the contemporary arts and artists of Rome?

I think the focus on craft and tradition. Hearing about the effects of living in an art historical site like Rome for young contemporary artists was fascinating and unfamiliar. That experience seems to clearly influence the forms and conceptual nature of the work there. It was surprising that the concept matter that seems so omnipresent in the contemporary arts that I see in the DC art scene had such a different aesthetic and priority in Rome.

Based on your recent experience in Italy, what roles, if any, do language and identity serve in the work of artists you met with in Rome? Has this affected your own strategies for sparking communication through art?

Absolutely. I think a lot of my work revolves around language already, and being in Rome surrounded by a literal different language, as well as different visual physical language was very affecting. I found that visual and physical language was the most engaging! The physicality of grand frescos, epic sculpture, fountains, piazzas, papal chapels—these felt like they were communicating so much. It sparked a reminder as to the power of curated and public spaces, and its relationship to the bodies and identities around and within them!

What are some new projects or directions in your work that you are excited to explore? Has your experience in Italy had a noticeable impact on your current practice or the work you have planned for the foreseeable future?

I am really excited about the flag series that is featured in my solo exhibition Tender Bits, “Flags for when you don’t know where you are.” It feels like I'm on the cusp of a new body of textile work based on that series, and I am really looking forward to working larger on these upcoming pieces as well. I also am hoping to explore some new ways of working with sculpture—I feel like I am still in awe of the reverence I experienced in public space in Rome, as well as the way the artists spoke about their craft and the aesthetics of beauty. I want to see what happens to the work I am making when I reframe or reteach. This applies to movement as well, in my dance work I think these ideas are already surfacing in new ways.

Overall, can you tell us 2 or 3 of the most significant takeaways from your experience in Rome?

It is possible to make room for awe and splendor in art alongside criticism.

Physical experiences of international spaces can be listened to as richly and intently as an artist talk, new friend, or unfamiliar languages.

I was reminded the power of collaboration and dialogue, and the importance on regularly stepping out of my artistic, political, and social comfort zones.

0 notes

Text

I Love to Hate You: Damon Arhos

Damon Arhos presents I Love to Hate You as an extension of his art practice, which seeks to expose the destructive nature of prejudice and uses his identity as a gay American as its frame. A native of Austin, Texas, Arhos explores how individual experiences influence gender roles, sexual orientation, and human relationships. A graduate of Maryland Institute College of Art in Baltimore with an MFA in Studio Art, Arhos lives and works in the Washington, DC metro area.

https://damonarhos.com/

You work in a variety of mediums. Can you discuss your process in determining what materials and media are most effective in creating your vision and delivering the message as a whole?

When I began working as an artist, I was a painter. Over the years, as my work evolved to address issues of identity, I began to realize that many of the ideas I wanted to express would translate better in other mediums. This is not to say that painting is not an effective way of providing a thought-provoking experience. I just decided to challenge myself to explore other ways of doing things—and, as such, in addition to painting, began producing sculpture, installation, videos, etc. Today, I consider myself an interdisciplinary artist. I always begin with the end— knowing what idea I want to convey to a viewer—and then analyze different options for putting things together. Sometimes I decide upon one way of doing things, and then in the middle of the process change course, as I find another approach or medium might work better. Most importantly, I never have a blueprint, so to speak, and have found that much of my reward as an artist is through the process of investigation.

Why are duality and conflicting narratives such important themes throughout your works?

I am one artist among many who use their work to highlight ways in which our culture opposes itself. Of course, we all have our own viewpoints that we use as bases for our art practices. With my own, I have chosen to explore issues of gender roles, sexual orientation, and human relationships given my identity as a gay American. We live in a time when those of us who are part of the LGBTQ community see so many dichotomies. For example, we can discuss the June 2015 U.S. Supreme Court ruling that established same-sex marriage in all 50 states versus the June 2016 Pulse nightclub shooting in Orlando, Florida. From my perspective, these two events—which occurred approximately one year apart—represent affirmation and rejection, the landmark of love and inclusion versus the tragedy of hatred and discrimination. Historically, these types of puzzling conflicts have existed for centuries. However, via my own art practice, I hope to show others what it is like to experience these contradictions every day.

Your work often references historical events or cultural symbols, do you find that current conditions also influence themes in your works and artistic practices?

Always! As an artist, and in the context of creating contemporary art, I do not believe that the past—in and of itself—is enough to capture and sustain anyone’s attention. In addition, I also do not believe that my own personal story is so compelling that it will captivate those who view my work. As such, I consistently aim to make my work relevant in the present moment and to access some common cultural experience. This certainly does not mean that I do not appropriate my own understanding of the history of art or my own life experiences. And, ultimately, even if I have my own overlay upon the work, viewers are bringing their own perspectives to it—which makes it even more important to strike a familiar chord. For me, the fun is in drawing the viewer in with something they think they know, then twisting this narrative so that their experience is completely different.

Why do you think it is so important to show the effects of prejudice in relation to modern-day issues and concerns?

I cannot deny that I am a pretty emotional guy. It never has taken a lot to hurt my feelings. And, over the years, I have been on the receiving end of bigoted behavior many times per my sexual orientation. While these situations definitely helped me grow, I never will forget how they made me feel sadness, isolation, and anger. Now that I am older, I more fully understand myself and others. I also know how to turn these types of experiences (when they happen, and sometimes they still do) into something more positive and more powerful. I often think of my younger self trying to sort through all of this, and hope that somehow, my work will help change outcomes for others. Ultimately, I know that prejudice creates and extends human suffering, and this is something that we all should work to eradicate.

With this exhibition, do you aim to reach particular audiences, perhaps those who have less immediate experience of the HIV/AIDS crisis?

I meant for the paintings in this exhibition to speak to the stigma of HIV/AIDS, highlighting the fact that the shame and humiliation associated with the disease persists. Of course, many years have passed since the epidemic began, and the many issues associated with it have evolved. However, as we all have diverse experiences of HIV/AIDS given our ages and life experiences, so too do we have differing awareness of these matters. The paintings provide a platform for discussion among everyone on this continuum of knowledge, as each has something to gain from these interactions. It is no accident that they depict that which is quite mundane—the bottle for a pill that manages, rather than cures, this disease. Everyone knows what it is like to take medication. Yet, does everyone know what it is to live with HIV/AIDS? And, what responsibilities, if any, does the work bestow once its seen? Do you glance and move along—or contemplate, discuss, and initiate change? Each of us must decide.

0 notes

Text

Farther Along: Mills Brown

Mills Brown lives and works in Washington, DC. She received her MFA in Studio Art from American University in 2017, and her BA in English and Art History from Wofford College in 2015. Mills has shown work in group shows in Washington, DC and has participated in the GlogauAir Artist Residency in Berlin, Germany.

www.millsbrownart.com

You note that your student’s interactions with the world were integral to this piece. How did you embrace that child-like curiosity and wonder to create your installation?

One of the most exciting parts of creating work for this show was expanding the range of objects I collect. This was certainly inspired by my preschoolers. There is no hierarchy for the objects they find at school and want to take home. As I wrote in my artist statement: plastic litter, delicate petals, and tiny living creatures are all treasures in their eyes. Not to mention sequins, beads, cicada shells, lost name tags, acorns, abandoned hair clips. Watching them find beauty and fascination in every piece of the world that crosses their paths has made a huge impact on me.

In effect, I’ve seen my own collecting grow past the expectations I previously held for what goes into an artwork. When I started searching for more and more found objects to use in my work, I naturally began to notice organic materials, too. What if I put sticks, bark, or even moss in a piece? When I realized it’s not that difficult to keep moss alive in a dark little box, I wanted more nature! Pressed flowers, lichen, and fungi made an appearance. Then a friend gave me a beautiful Monarch butterfly she had found (with the thought that I might like to study it under my microscope), and it dawned on me that this, too, could hide in a collage. I decided to build and ornament a shrine-like home for the butterfly, which became the first piece in the series. When I began looking for more dead bugs, I not only found (or was given) WAY more than enough, but I also began to notice other details in nature that hinted at stories of unknowable animal lives. A fallen nest, a broken robin’s egg, many seeds and shells, and the bones of a deer all made their way into my collection. I think that seeing these things as valuable and wanting to collect and protect them has a lot to do with embracing the child-like curiosity and wonder inspired by my students.

How do fairy tales and Southern gothic influence your work?

I’ve always been a reader and have found that my favorite books are very connected to my artistic interests. Lately, I’ve become interested in the uses of enchantment, and wondered what makes the fairy tales I love so absorbing. I think that the appeal of the fairy tale is not simply in the happy ending. Rather it is their danger and difficulty that inspires wonder. But they consistently maintain a promise of hope and offer examples of morality. Southern gothic and magical realism stories contain a similar darkness, and my favorites put me into a world that is at once unsettling, eccentric, and hauntingly beautiful. I look for a similar balance of darkness, hope, and mystery in my work.

What made it so significant to identify the feeling and act of protection?

Being in a position of responsibility to protect small children, and then watching them want to protect the things they find, has been a large part of this series. But I think the work is really about the futility of this desire to protect. I haven’t actually protected the bugs in my pieces, because, of course, they were already dead. We can protect children to a certain extent by keeping them out of unsafe situations, but we can’t shield them from life’s difficulties. Despite the futility, I find so much beauty in this collective effort and desire to protect.

At the opening of my show, I saw this desire reflected back to me. Many people asked me what I did to preserve the bugs. I loved this! I didn’t do anything to preserve them except remove them from their setting (the floor, the windowsill, the sidewalk) and put them in mine. I’m not sure what the process of decay will be or what this will look like for the artwork. But when I was asked this question so many times, it seemed to be with the expectation that I had embalmed these insect bodies with chemicals to make them last. I laughed because I have no idea how I would even begin that process. But I also loved the confirmation that my viewers, too, want to see delicate things last, to have them kept safe and beautiful.

Your works have a sense of nostalgia that brings the audience back to childhood. How does this recall of memory shape the experience of your installation, in your opinion?

Brown: I hope the audience remembers what it’s like to have the active imagination of a child when they look at my art. Children do not already know what things mean and have the freedom to construct their own narrative. I remember, as a child, having the ability to easily travel into and between imaginary worlds, being fully present in whatever story I was pretending to be in. I create these pieces in hopes that they will be small but elaborate worlds, too, with hidden details that reward you for looking closer, asking the audience to immerse themselves in a story.

One of your works requires audience participation. What made you want to include the viewers in this way? Why was this piece chosen to be interactive while the others were not?

I decided to ask the viewers to participate because this means asking them to look closer. If they have to open the box themselves, taking an active role in revealing the piece, I hoped they would be more curious to discover what’s hiding inside. They are no longer just the viewer, but now an explorer. If people are asked to touch a piece of artwork in a white wall gallery, they also feel like they have to be very careful, calling on closer attention and alertness. Ideally, I would want more (or all) of my bug boxes to be interactive. It became clear that this was the only practical interactive piece in this series because the others actually were too fragile. I think that going forward, finding different ways to allow for audience participation will be an exciting new part of my practice.

0 notes

Text

Audio Playback: Veronica Szalus

Veronica Szalus lives in the Washington, DC metropolitan area where she creates installation art. In 2011, Veronica received a Virginia Museum of Fine Arts Fellowship and has shown her work at several galleries including The Mansion at Strathmore in North Bethesda, MD and the Cade Art Gallery in Anne Arundel, MD. She is also a member of Studio Gallery in Washington, DC. She is employed at the Northern Virginia Fine Arts Association as the Executive Director.

www.veronicaszalus.com

The use of cassette tapes shows an emphasis placed on the past. How did nostalgia play a role in creating this installation?

Nostalgia had very little to do with the concept of creating an installation using cassette tapes other than being an object from the past that could easily manipulated. My work focuses on transition and the cassette tape is an ideal object to capture that phenomenon. I find cassettes interesting because of their orderly shape and size and the ability to alter that appearance by pulling the encased tape from its protective shell rendering it useless as an audio medium in its original form.

There was unavoidable nostalgia slip during the process of collecting and assembling tapes for Audio Playback. For the tapes affixed to the floor, I wanted to highlight the broad range of content cassettes contained, including but not limited to volumes of music, books and magazines on tape, exercise tapes, interview recordings, classroom learning, and much more—basically anything audio. While going through the tapes I was reminded of how much this content captures the culture of the 80s and also note that much of this content is still in use today, compressed into mp3 files.

How do transitions and transformations inspire you in artistic creation?

I have a deep interest in creating environmental pieces that explore both the conceptual and physical phenomenon of transition. I am fascinated by the fact that everything, at all times, is in a state of evolution. From the macro to the micro, nothing is permanent and this defines our existence. I am continuously seeking to explore this through volume and scale, new forms, and observation of the intersection of natural and manufactured materials. Through the use of these materials, I embrace fragility, balance, and porosity while observing subtle and overt shifts caused by the impact of time.

How does the auditory aspect of the installation prove to increase the impact in your opinion?

The thing I like about the auditory aspect of the installation is the incorporation of another media that is wholly linked to the materials in the installation. The original plan for using audio was to provide an interactive component inviting the viewer to select and play a series of cassettes, finding that some tapes work and others have been physically impacted and no longer function. However as this particular installation developed, a quiet serenity emerged coupled with active lines of movement with light, so I took a step back, and utilizing the advice of Cory Oberndorfer, I switched to capturing the sound of the functioning technology itself rather than playing the content. I think this helps frame the impact of visual elements while leaving sound open to interpretation and takes the viewer back to the beginning and now mostly obsolete mechanics of cassette technology.

How would you describe the relationship we have with obsolete objects such as these in the modern day?

The cassette tape is obsolete, yet the content is not. I think you can make that comparison with many objects. We still hear sound with our ears, we still use our voice to produce sound and we still use devices to play audio. Today the amount of content that can be transported is significantly higher on handheld devices and audio technology is more versatile and reliable.

But don’t cast cassette tapes completely into the obsolete objects category yet, they are still used for recording interviews and books/magazines on tape and there is a cassette revival going on with startup garage bands and independent labels, and there has also been an uptick with major labels following the trend.

What about the cassette tape specifically drove you to create this work?

Cassette tapes provide excellent material to represent transition—they are colorful and have a distinct retro-cool look and feel. The shape of the cassette provides a uniform visual that works very well in multiples and can very easily be transformed when the magnetic coated tape is pulled from its plastic container. In addition, there is a feeling of freedom and randomness when one pulls something apart that is no longer used as originally intended, and I wanted to capture that in Audio Playback.

0 notes

Text

To Future Women: Georgia Saxelby

Photo: Kate Warren

Georgia Saxelby is a Sydney-born, US-based installation artist and is currently an Artist-in-Residence at the art and social change incubator Halcyon Arts Lab in Washington, DC. Her interdisciplinary practice explores ritual and sacred space and their role in re-imagining and re-forming our cultural identities and value systems. Saxelby creates installations that are rooted in participatory and feminist practices and traverse sculpture, performance and architecture. While in Washington, DC, Saxelby is also a Visiting Scholar at the Sacred Space Concentration of the School of Architecture at Catholic University of America. In 2016-17, Saxelby worked with the renowned architecture studio Diller Scofidio + Renfro, and was awarded three prominent artist grants to undertake a series of international sacred space mentorships and residencies. Saxelby was chosen to speak at the ninth International Architecture, Culture and Spirituality Symposium in 2017 on her practice.

georgiasaxelby.com

Why did you decide to embark on this project?

My art practice plays at the intersection of art, architecture and performance and is primarily concerned with investigating the role and importance of ritual behaviour. I’m interested in the way we perform and embody our cultural value systems through ritual gestures, as well as the material and visual cultures that result from our collective symbolic activities. This project developed out of a particular line of questioning: in what ways can ritual become a powerful and unique vehicle for social change? What are women-driven methods of passing down cultural knowledge and skills? How can I, as an artist, contribute to a new kind of cultural heritage for tomorrow?

A central tenet of my practice is the acknowledgement that what we mark as special and significant reveals and defines who we are. Knowing that I would be in Washington, DC for the one year anniversary of the Women’s March, I wanted to create a work that would mark this occasion as significant. I wanted to do this through the platform of art because I’m interested in transforming artistic contexts into meaningful sites of symbolic action—platforms for rituals to take place that can ripple out to affect how we think and feel in our everyday lives.

History has a tendency of forgetting the contributions of women, and I wanted to make sure our stories were told by us—by anyone that has been impacted by the Women’s March and #MeToo movements or by anyone who wants to take part in this conversation. I wanted to re-activate cultural institutions and spaces that were used during the Women’s March, and invite them to play a role in guarding our stories for us.

One intention of this artwork was to shift the focus of the conversation for a moment on who we want to become as a culture in regards to our relationship to women. I think imagining futures is a very powerful exercise. By asking you what you want to say to future women, and what changes you would like to have taken place for the woman reading your letter, you must envision and articulate what that change actually looks like for you. Only then can we start to reverse engineer those possibilities and understand our role now in taking continuous steps towards making them a reality.

Photo: Kate Warren

Your work often engages with women's issues and feminism. Where does this interest stem from?

I’ve always had an urge to support women’s agency, self-determination and self-representation.

Through research, constant reflection and conversation, as well as Art Theory and Cultural Studies at university, I learned to better see the cultural structures at play which work to disempower or exclude women from decision-making at every level, and one cannot go back to unseeing. As a young woman brought up to see the world as my oyster, and then growing to observe and understand the limits the world would in fact place on me because I am a woman, I have a vested interest in transforming the way women are represented, perceived by others and by themselves. Women have been persistently represented as passive objects rather than transformative subjects in our culture and history. I am trying to exercise my own ability to transform my environment, as well as contribute to women being understood and treated as connected, active and unstoppable agents of change.

Have you written a letter yourself? Are you able to share some of what you wrote?

As the orchestrator of the experience, I’m always conscious of my involvement becoming didactic for others so tend to see my role as first and foremost holding space for other people’s engagement until the last moment or a private moment at the end of the piece. So, I will be writing my letter in July before the Washington archive is sealed and becomes a time capsule.

It must be surreal knowing that women - some of whom aren't even born yet - will be reading these letters in twenty years time. What do you hope that these women will gain from this?

I hope that in reading our letters future women may be able to understand not just the significant events occurring at this time but our feelings and internal thought processes in reaction to them. I hope our archive reveals the intimacies of history. Change comes slowly and is not a given or a linear progression. I hope these women will understand how desperately we want things to be different for them, and are reaping some of the rewards of the vows we have made to make that a reality for them.

Right now it feels more possible than ever to speak loudly about gender issues in mainstream platforms, but it hasn’t always been like that and it might not be again. So to capture our sentiments now, when we feel able to speak more openly, is important. I want the generation of women that will come after us to know that we were thinking of them, so that they may never doubt their place and role in this world.

Photo: Kate Warren

Why did you decide to do this via traditional letter writing and not a digital format?

There’s a specialness to letter writing. I wanted to elevate the experience of writing to future women to have a ritual significance, so that people took the time to unravel their thoughts and understand their reflections. I wanted to provide a platform of expression that was long-form, slow, in contrast to the abridged immediacy and crispness of social media in a digital information age.

The materiality of pen or pencil to paper, the rhythmic flow of capturing thoughts as we write—sometimes things come out of our pens that we didn’t even know we felt. There’s a privacy to the experience of writing a letter and a logic to the way someone approaches the page—they draw, underline or write larger or harder to emphasise a point. And there’s something so intimate about seeing someone else’s handwriting. There’s so much personality to it—you feel like you get a glimpse into someone.

Letters are so personal. They are messages sent from one person to another about a common concern. They are cross-cultural and ancient forms of communication, and they have a tradition of revealing alternative and intimate perspectives in history.

In 20 years time the screen will play an even larger role in our lives and cultural landscape, it will affect the way we process and understand the world, as it is already beginning to do. Museums, too, will play a different role. I think it will be so interesting in 2037 to experience these letters as physical artifacts, like relics.

The work champions the power of generational storytelling. Do you think that Western society has in some ways lost its methods of generational storytelling? i.e. indigenous cultures often use storytelling as a way to instil moral values, but this seems to be lacking in western culture.

Absolutely. I was recently reflecting on how as I grow older—or maybe because of everything that’s been happening—I feel increasingly drawn to seeking out and listening to the stories of older women. There have been times I was at The Phillips Collection checking on the installation and would wind up in conversations with visitors who would talk to me about their reaction to the piece or their experience of the Women’s March. I was lucky enough to have some incredibly personal conversations with older women who had so much wisdom to share, who have been through what I’m going through as a young woman contending with my culture.

The letters I’ve read from older women, and men, passing on advice, connecting their experiences from marches and movements in the 60s and 70s to what’s currently occurring, revealing what their hopes were then and analysing what has comes to pass, has been so touching, powerful and informative.

Certainly I think oral histories and intergenerational exchange are woefully undervalued in Western contemporary culture. Stories are intimate histories performed and relived. The act of sharing generational stories is crucial to processing and understanding where we’ve been, in order to know where we’re going.

Do you think that part of the value of the project is the cathartic process of actually writing the letter and what that means for each person? How so?

Yes of course. Seeing people in deep concentration as they’re writing their letters, in some cases being lucky enough to listen to them talk to me about everything it brought up for them afterwards, it can be an emotional and sometimes confronting process. The act of self-expression is powerful. The #MeToo movement, and the Women’s March, allowed for the expression of things previously inexpressible in a public setting with the knowledge that your expression would be supported and backed. This is the same thing - people know they can write freely in this setting, that its a safe space, that their letter - and therefore their act of expression, their point of view - will be respected and cared for for a very long time.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Nine Patch: Olivia Tripp Morrow

Olivia Tripp Morrow received her BFA at Syracuse University, graduating cum laude with Sculpture in December of 2012. Her most recent works are video and sculptural installations that address concepts relating to beauty, intimacy, memory, sexuality, and the commodification of women’s bodies. Morrow's work primarily utilizes found and donated textiles as material, which are imbued with social and cultural values as well as personal histories. Through her work, Morrow draws connections between status quo notions of beauty/luxury and the perpetuation of harmful social norms and expectations placed on women and girls. Morrow's work has been exhibited nationally and internationally, and she has permanent installations and works on-loan at the National Institute of Health's Clinical Center in Bethesda, MD, the Anacostia Arts Center in Washington, DC, and the Arlington Art Center in Arlington, VA, where she is a current Resident Artist.

www.otmorrow.com

Your work addresses the human body and the experiences of human bodies through abstract installations. Can you tell us a bit about how you arrived at this theme?

The core of my work and studio practice comes from a personal context. I was twelve when I discovered that my body was perceived by my peers as a mishmash of individual physical parts entirely separate from each other, and which could be rated according to a numerical scale. In high school I learned that my value as a person could be defined entirely by my physical appearance. As an adolescent, my appeal for perfectionism mutated into a crippling fear of making mistakes or being perceived by others as inadequate—physically or otherwise. (This was before smart phones or Instagram, so I would imagine it's only getting harder for young girls today.) Grappling with notions of beauty, bodies, and intimacy, as well as social structures that attempt to exclude and invalidate people who don't fit neatly into conventional measures of beauty, have been important to why I create work and what I want it to do.

It's practically impossible to filter out the incessant bombardment of media and advertisements that reinforce harmful and equally narrow definitions of beauty, bodies, and gender-appropriate behaviors, all of which normalize obsessive fixations on so-called imperfections and breed exclusivity. Once I realized what I was looking at I saw it everywhere: relentless reminders to buy whatever product or thing that would seem to simultaneously present and offer solutions to the apparently boundless inadequacies of my appearance. This subliminal conditioning can be highly effective, but knowing what strings these industries are trying to pull at can at least give us a chance to resist them.

What is the purpose of using donated materials in your work?

For the past few years my work has been driven by donated women's clothing, undergarments, bedsheets, and other used textiles that I began collecting in 2015. Along with these donated items, many women shared personal stories associated with them: Fond memories of family, travel, and past lovers were contrasted with darker recollections such as an outfit that someone was wearing when they were assaulted. Like much of my favorite work by Sonia Gomes, Shinique Smith, and Senga Nengudi, whose found and donated materials seemed dense with meaning upon arrival, the donated textiles I received were imbued with personal history, familial tradition, social narrative, and political context.

In the context of the current exhibition at Hillyer, Crochet II is a single-channel looped video that utilizes a blanket that was crocheted by my great-grandmother. The significance of the blanket itself lies in its personal and familial sentimentality, and implications of domesticity. The intricate, open floral patterning of the blanket and mesmerizing shapes that at times resemble female genitalia might give the initial impression that it is delicate and decorative. However, its actual strength and durability defy these assumptions once it's discovered that a person is moving around underneath, pulling and stretching the fabric to its limit. Similarly, the five printed photo quilts in Nine Patch are comprised of thousands of selfies taken while underneath used crocheted blankets, and simultaneously conceal and reveal my body.

While I grew up using crocheted blankets and handmade quilts as functional objects that were made by family members and passed down over generations, I never saw them being made by those family members. By the time I was born, the generation that labored over these textiles had passed, and their tradition and skill set largely disappeared with them. It was only as an adult that I began to consider the labor that went into their creation, and all the implications of that labor in the context of times and places that I never lived in.

Do you plan out your ideas meticulously before making an installation, or are you more improvisational? Can you take us through your creative process?

My materials and their physical properties guide my formal decisions while creating new work. I spend a lot of time experimenting with and discovering the limits of materials, such as how much something will stretch or bend, the weight something can hold, the shapes it can take, the way it might transform in different spaces. Even when I have a clear idea about some new piece or body of work, I rely on my intuition and remain willing to abandon parts of the work in exchange for a potential discovery that I might not find otherwise. Executing procedural steps has never been very exciting to me, so it's often the curiosity about "what would happen if..." that leads me forward in my studio. There's freedom in this process; permission for boldness, taking risks, and failure from which better ideas are (sometimes) born.

You entered art school to study painting and illustration. What drove you to make a shift into abstract installations?

Having started my early work as a painter, I am influenced by formal techniques of painting: color used to create receding or expanding space, light that reveals/conceals, and the varied expressions of human emotion. But as a freshman in college I found working exclusively with paint and 2D surfaces limiting. I wanted to get lost in experimentation with new materials and processes, so I transferred to the Sculpture department. I am also captivated by the potential for artwork to completely transform my relationship to objects and physical space. Exploring scale and spatial relationships and considering the ways we navigate spaces translates well into this medium. In my third year as an undergraduate student, I realized that it was possible to essentially make "paintings" that people could walk under, around, or through, and which could be experienced differently from a multitude of perspectives. Installation has dominated my practice ever since.

What concepts are you currently exploring in your studio, and what kind of work can we expect to see from you in the future?

Lately I've been working really hard to push past certain comfort zones in my studio practice. The photo quilts in Nine Patch and the work I made for a simultaneous two-person show (called Within/Between, with artist Jen Noone at the Arlington Art Center) were an important departure from that comfort zone. While making work for Within/Between, one of the things that both Jen and I were reflecting on in our own way was materiality and function. One of my pieces (Ribbon House, 2018) is a large, shelter-like structure that is robust and meticulously constructed using scrap and found wood. Instead of hardware or glue, the structure is held together with materials normally considered decorative or inane: ribbons and beads.

It was a huge challenge to put these two exhibitions together within a week of each other, but the works in each were influenced by each other, so it feels really good to have them open simultaneously. Right now, I am in the middle of changing studios, but I'm excited to start a new residency at the Arlington Art Center and to get back to work.

#oliviatrippmorrow#ninepatch#dcarts#hillyer#acreativedc#arlingtonartcenter#artistinterviews#june2018#installationart

0 notes

Text

Measuring the Weight of Longing: Gayle Friedman

Gayle Friedman is an artist who was raised in Birmingham, Alabama. She lives and works in Washington, DC, where for the past decade she’s been a jeweler, teacher, and the founder of Studio 4903, a group art studio space. Friedman received a DC Commission on Arts and Humanities Fellowship Award in 2017. In addition to her solo exhibition at Hillyer, Friedman also has work in the exhibition Intimate Gathering opening June 2, at WAS Gallery in Bethesda, MD. Friedman is an artist in residence at Red Dirt Studio in Mt. Rainier, MD.

gaylefriedmanart.com

You often present your ceramic work in tableaus inside boxes, much like jewelry. How has making jewelry informed your work?

I actually see a lot of jewelry in my work—some of it shows up in the techniques I use that are taken directly from metalsmithing, such as incorporating soldered chains in a piece, or using rivets to cold-connect things. I also use sterling silver and even gemstones in some of my work. Several of the pieces in this show incorporate wire to attach or wrap things—all common in jewelry-making.

In this show I’m working with a lot of previously used things—I find their historical and emotional content very compelling. I do the same thing with a lot of my jewelry. In fact, I love working with people who want me to take something they’ve got and transform it into something more relevant or that they can use in a new way. Several years ago I made a series of reclaimed fur pieces that began when a friend gave me a collar from one of her grandmother’s fur coats.

Finally, I think I pay attention to minute details much as a jeweler does, which is easier to do when a piece is small. However, I’m excited to be going larger and breaking free of some of the size, weight and even balance restrictions necessary when making functional jewelry.

Tools are a dominant motif in your work. Can you talk a little bit about your fascination with tools in general?

The tools go way back to my early childhood. Summers in Alabama are hot and I’d go down beneath my grandparents’ house to the dirt-floored basement to cool off and play at Papa Izzy’s workbench. I can still smell it—that kind of musty, iron aroma. He owned a hardware store before the depression and had quite a collection of tools. Just the objects themselves fascinated me. I remember being especially fond of the vice and his hammers. After he died, dad got all of his tools and created a really cool shop in our basement, where I’d often go to seek refuge. Dad was always doing projects around the house but he never showed me and I never asked how to use any of his stuff. It sure made an impression on me, though.

And after he died, what I most wanted were some of his old tools. At the time I had no idea what I’d do with them. All of the work I’m doing now began when I made a mold of dad’s ball peen hammer and began casting clay replicas of it.

What does your process look like when making your Delftware pieces? Does your photography of decomposing and broken plant materials inform how you treat porcelain?

I studied Anthropology in college and did several digs in Alabama during and after school. I spent a lot of time in the dirt, searching for the tiniest pieces of information. Almost everything we found was broken.

Many of the things I make feel like artifacts, and while they’re not necessarily dirty, I often tear or break them because I figure that just about everything ends up that way. Sometimes I’ll break something on purpose and glue it back together again. Many of the delft pieces in my mom’s collection broke over the years, and one of my dad’s chores was to glue them back together. In fact, this week, a vase he had repaired broke apart again and I had to re-glue it. It was so strange to think that he was the last person to have paid close attention to this crack; his hands were the last to touch the glued surfaces and now I was revisiting them. It felt so intimate, like we were having a conversation.

I’m enamored with my compost pile and find the decay to be quite beautiful. The rust I use in many pieces is a part of that process of decay in metal. We tend to think of metal as dead, but I really like how inanimate materials also have a sort of life that shows up through time and their disintegration or exposure to oxygen.

Tell us about your experiences with Studio 4903. Does sharing studio space with other artists impact your work?

I am so happy to work in shared art studio spaces. I founded Studio 4903 12 years ago because I didn’t want to work out of my home. I wanted to be part of a community of people who I could problem solve with, bounce ideas off of, be inspired by. I also have a firm belief that many together can accomplish much more than an individual on her own. Interestingly, I’m now in two shared studio spaces! I’ve been doing an artist residency at Red Dirt for about a year and a half, and it’s there that I’ve expanded my process beyond creating jewelry.

I find it really interesting how working in proximity to others can affect my work in subtle ways: I’ll try a color of paint I’ve never used before, or tear something and realize that one of my studio mates tears and cuts a lot of her work. And then there’s the conversations we have, sometimes in structured meetings or critiques, but often over a quick lunch or chance encounter. The dialogue helps shape who I am as an artist. I’m curious by nature so I want to know what others think and feel—about what they’re doing as well as about my work. These moments give me ideas, things to incorporate or reject, often a new or better way of looking at my work. They can be very challenging and even crazy-making, but I love it all!

How has your work evolved over time, and what are your next steps in your body of work?

Many people don’t know that I was making ceramic sculpture back in the 90’s. I got lured away from the studio to help found an alternative school, Fairhaven School, in Prince George’s County, where I spent 7 years. When I left the school I knew I wanted to immerse myself in a creative practice again, but didn’t really know where to begin. My ceramic pieces had begun large but had gotten smaller over the years, so it seemed natural to explore jewelry. I loved the idea that I could create these intimate art pieces that people would literally carry on their bodies. Early on I made more conceptual jewelry, such as a series on waste and luxury. One example from that series is a pair of plunger earrings made of silver and terra cotta clay, with a tiny diamond hidden up inside the clay part of the plunger—as if any plunger could tuck away something as precious as that! But I really wanted to have a larger audience for my jewelry, so I began making more functional, accessible work.

More recently I’ve realized that I have different kinds of questions I want to try and answer. That’s where I feel most engaged right now. I’m interested in how people in other cultures treat, use and discard family items and heirlooms. I’m going to spend time doing some research on that and see how I might be able to collaborate with anthropologists and artists.

I’ve also been interested in doing more mantel installations. I think there are lots of people who’ve stored things in boxes because they don’t want to throw them away, but don’t know what to do with them. I’d love to collaborate with them and their stuff—to open those boxes and reimagine those things in new ways.

#gaylefriedman#artistinterviews#hillyer#june2018#acreativedc#deltware#sculpture#installationart#jewelry#measuringtheweightoftime

0 notes

Text

Objectual Abstractions: Q & A with Emilio Cavallini

English | Italiano

A renowned fashion designer, Emilio Cavallini is known the all over the world for his innovations in stockings and hosiery. In a career spanning three decades, Cavallini has collaborated with design houses ranging from Mary Quant to Dior, Balenciaga, Alexander McQueen, and more. Beginning in 2010, he gave up designing for women’s legs in order to devote himself entirely to designing on canvas and creating fine art, but not too much has changed—we can still find his unique artistic expression, dedication and elegance in his practice.

Cavallini’s fine art was first displayed to the public in early 2011 for a solo exhibition at the Triennale Expo in Milan. Emilio Cavallini’s masterpieces draw the spectator’s gaze into a new mystical world, seemingly comprised only of stockings. This trascendental effect is achieved by the perfect union between nylon thread, emptiness, mathematics and genius. In his hands, new mathematical discoveries, through complex processes, are developed into works of art.

In partnership with the Embassy of Italy and the Italian Cultural Institute, IA&A at Hillyer is currently exhibiting a retrospective of Cavallini’s works, including Fractals, Diagrams, Bifurcations and Actual-Infinity. Concurrently, the Italian Cultural Institute is exhibiting three stunning masterpieces inspired by the Italian Mannerist painter of the 13th century, Giacomo da Pontormo, creating an original union between old painting and new mathematical discoveries of our century.

Objectual Abstractions is on view at IA&A at Hillyer and at the Italian Cultural Institute (appointment only) from May 4-27, 2018.

_ _

What makes nylon thread and stockings your medium of choice? Do you find there are mathematical principles inherent to the production of hosiery?

It was in designing and producing my first stockings that I identified the tools with which I have built my dream of creating art. The mathematical principles were applied after I designed and produced samples of stockings.

Do you draw your ideas before executing them? Can you tell us a little bit about how you go from concept to finished product?

The socks are designed so that they can be made by machines following my instincts for making fashion. All of my designs are also based on my knowledge about the world of art both ancient and modern.

What are your major inspirations? In conjunction with the exhibit at Hillyer, the Italian Cultural Institute is also showing some of your artworks inspired by Jacopo da Pontormo’s paintings. What drew you to these Mannerist works?

My inspiration comes from the street, commercials, movies, television, and from my fondness for art of the Greek Classical period and the Renaissance. Colors are important, and from the Renaissance I have drawn great inspiration from Pontormo, Rosso Fiorentino, Michelangelo, Raffaello, etc. Thus my colorful fractals were born, drawing on shades prevalent in those works.

You spend your time in Milan and New York. What has it been like to show your work in LA and now in Washington, DC?

Living in Italy, where art is very invasive and makes you lose your sense of what is modern, it was by hanging out in New York in the 60s that I gained strength and courage to undertake not only making fashion but also the creation of works of art. My passion for mathematics made my artistic work easier and more unique. Exhibiting my work not only in Italy but also in New York and Los Angeles and now Washington [DC] has been a great pleasure because I have been able to show my work to many more people.

What concepts are you exploring in your new work?

I am juxtaposing the mathematical concepts of my works with those of light and the colors of the rainbow of which it is composed.

Objectual Abstractions: Intervista con Emilio Cavallini

English | Italiano

Emilio Cavallini è oggi conosciuto in tutto il mondo prevalentemente in quanto stilista di moda di fama internazionale. Con una carriera che si estende per tre decenni, Cavallini ha collaborato con differenti case di moda, da Mary Quant a Dior, Balenciaga, Alexander McQueen e altre. Smise di vestire le gambe delle donne a partire dal 2010 per dedicarsi completamente al vestire tele, ma poco cambia; continuiamo a trovare la stessa arte, dedizione ed eleganza.

Per la prima volta nel 2011, le sue opere vengono finalmente mostrate al pubblico in occasione di una mostra personale offertagli dalla triennale di Milano. I capolavori di Emilio Cavallini cuciono lo sguardo dell’osservatore in questo nuovo mistico mondo apparentemente costruito dalle sole calze. Basta poco, peró, per realizzare che questo effetto trascendentale è dato in realtá dal precisissimo accostamento tra calze, vuoto, matematica e genialitá. Così le nuove scoperte matematiche, attraverso una elaborata sfida con la complessitá, diventano finalmente oggetto artistico.

A IA&A at Hillyer sono esposte venti delle sue opere inclusi Frattali, Diagrammi, Biforcazioni e Attuale-Infinito, in collaborazione con l’ambasciata italiana e L’Istituto Culturale Italiano dov’è possibile trovare tre grandi capolavori che prendono ispirazione dalle opere dell’artista manieristico italiano del sedicesimo secolo, Pontormo. Così ci viene presentato questo originalissimo sinolo tra vecchi dipinti e le nuove scoperte matematiche.

Objectual Abstractions è in esposizione a IA&A a Hillyer e all’Istituto Culturale Italiano (solo su appuntamento) dal 4 al 27 maggio 2018.

Cosa rende le fibre di nylon e i collant la tua scelta attraverso cui realizzare opere d’arte? Trovi la presenza di principi matematici anche nella realizzazione di calze?

È Stato disegnando e realizzando le prime calze che ho individuato nelle stesse gli strumenti con cui costruire il mio sogno di fare arte. I principi matematici sono stati applicati dopo che ho disegnato e realizzato i campioni di calze.

Disegni le tue idee prima di realizzarle? Ci diresti qualcosa in merito al processo da concetto a prodotto finito?

Le calze vengono disegnate, in modo che possano essere realizzate dalle macchine, seguendo il mio istinto nel fare moda. Tutti i miei disegni seguono inoltre la mia conoscenza del mondo dell'arte sia antica che moderna.

Quali sono le tue maggiori ispirazioni? Contemporaneamente all’esibizione a Hillyer l’istituto culturale italiano sta esibendo alcune delle tue opere d’arte ispirate dai quadri di Jacopo da Pontormo. Cosa ti ha condotto a queste opere in chiave mannieristica?

Le mie ispirazioni vengono dalla strada, dalla pubblicitá, dal cinema, dalla televisione oltre che la mia passione per l'arte classica greca e rinascimentale. I colori sono importanti e dal rinascimento ho tratto grande ispirazione come da Pontormo Rosso Fiorentino Michelangelo Raffaello ecc. Sono nati così i miei frattali colorati attingendo opera per opera i colori predominanti

Passi il tuo tempo tra Milano e New York. Com’è stato esibire il tuo lavoro a Los Angeles e attualmente a Washington, DC?

Vivendo in Italia, dove l'arte è molto invasiva e ti fa perdere la cognizione di ció che moderno, è stato frequentando New York dagli anni 60 che mi ha dato forza e coraggio di intraprendere oltre che fare moda la realizzazione di opere d'arte. La mia passione per la matematica ha reso il mio lavoro artistico più facile ed unico. Esibire il mio lavoro oltre che in Italia a New York e Los Angeles ed ora Washington [DC] è stata una grande soddisfazione poter far conoscere il mio lavoro sempre a più persone.

Quali concetti vorresti affrontare per le tue opere future?

Sto affiancando il concetto matematico delle mie opere a quello della luce ed ai colori arcobaleno della sua composizione.

0 notes

Text

Drift: Q & A with Carrie Fucile

Sound is integral to your artwork. Can you tell us how you began to discover sound as a medium to incorporate in your work? What are some of the challenges of working with sound?

As a young person, I was trained classically as a pianist and a vocalist. I first became aware of alternative modes of music-making in high school, when I was introduced to 20th century composers such as Samuel Barber and John Cage. Seeing and hearing a prepared piano was likely the source of my enthusiasm for sound. Later, when I was living in New York in my early 20s, I started to witness “sound art” at various museums and galleries. I very distinctly remember sitting in the dark at the Whitney Museum, wowed by a Maryanne Amacher piece. Later, in graduate school, I began making videos, and people often commented on the strength of the sound. I became drawn to professors, courses, and venues that emphasized sound art and experimental music. This was the jumping off point for my subsequent work. In retrospect, it seems natural that, as both a visual and musical person, sound became the focus of my creative output.

Sound can be challenging because things can go wrong. Therefore, anytime I do a performance or an exhibition, there is a chance something might not work or that things could break down. I have learned to expect these setbacks, but it does not make me any less anxious!

How do you relate to improvisation in your work?

Improvisation factors into my performance work. I always have a structure for what I will do, but I allow room for improvisation so that things are fresh, exciting, and interesting.

Can you guide us through your creative process? Are there other artists (visual, musicians, writers, etc) that influence your work?

My creative process involves a lot of thinking and then an “a-ha!” moment where I realize something I want to try out. I then go make it or propose it and make it. Usually there is a part of the work that I have no idea how to do, and I end up teaching myself how to execute it. I think that it is really important that I consistently learn new things.

I have been influenced by countless artists through the years. Currently, I am very inspired by the work of Gianni Colombo, Rolf Julius, and the writing of Hito Steyerl.

In “Drift” you are dealing with a lot of big issues—territorial and bodily boundaries, political upheaval, and global capital. How do you bring all of these topics together? Is it important for you that the viewer understand the background and intent of each piece while they experience it?

As an artist, I posit myself as an outside observer who makes connections. I see certain patterns that exist and I explore them. It is great if the viewer gets my intentions, but not necessary. Once the work is out there, it is up for grabs and I am always thrilled to hear other interpretations.

How has Baltimore’s art scene influenced your work?

Baltimore’s art scene has always allowed me to be myself. I am very grateful for such an inspiring, open-minded, and supportive community. People here are interested in making art for art’s sake and engaging with each other. I love how there is always a welcoming venue for a project. People are genuinely excited to share work and foster a dialogue.

0 notes

Text

Lines, Folds, Bends and Matter: Q & A with Anne Smith

Your works in To Bend / To Fold focus heavily on the use of black, which seems like a heavy contrast to your more colorful Potomac Prints series. How did you arrive at this mostly monochrome body of work?

For some reason, I have tended to make dense images (that is, with lots of material) for quite a while now. The first drawing I ever did that involved a really dense application of graphite was in 2005, and although the subject matter was very different, it took on this reflective quality with light, setting up a situation in which the image would change depending the viewer's relationship to it and the light. So, I was hooked then on that interest in light reflection as well as density, and eventually have found myself in the place where I am now—making these charcoal and graphite drawings.