Text

@gentlecrisp submitted: orchid bee collecting pine sap in southwest florida :)

Orchid bees are some of the best bees, I think.

430 notes

·

View notes

Text

"In 2021, scientists in Guelph, Ontario set out to accomplish something that had never been done before: open a lab specifically designed for raising bumble bees in captivity.

Now, three years later, the scientists at the Bumble Bee Conservation Lab are celebrating a huge milestone. Over the course of 2024, they successfully pulled off what was once deemed impossible and raised a generation of yellow-banded bumble bees.

The Bumble Bee Conservation Lab, which operates under the nonprofit Wildlife Preservation Canada, is the culmination of a decade-long mission to save the bee species, which is listed as endangered under the Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation...

Although the efforts have been in motion for over a decade, the lab itself is a recent development that has rapidly accelerated conservation efforts.

For bee scientists, the urgency was necessary.

“We could see the major declines happening rapidly in Canada’s native bumble bees and knew we had to act, not just talk about the problem, but do something practical and immediate,” Woolaver said.

Yellow-banded bumble bees, which live in southern Canada and across a huge swatch of the United States, were once a common species.

However, like many other bee species, their populations declined sharply in the mid-1990s from a litany of threats, including pathogens, pesticides, and dramatic habitat loss.

Since the turn of the century, scientists have plunged in to give bees a helping hand. But it was only in the last decade that Woolaver and his team “identified a major gap” in bumble bee conservation and set out to solve it.

“No one knew how to breed threatened species in captivity,” he explained. “This is critically important if assurance populations are needed to keep a species from going extinct and to assist with future reintroductions.”

To start their experiment, scientists hand-selected wild queen bees throughout Ontario and brought them to the temperature-controlled lab, where they were “treated like queens” and fed tiny balls of nectar and pollen.

Then, with the help of Ontario’s African Lion Safari theme park, the queens were brought out to small, outdoor enclosures and paired with other bees with the hope that mating would occur.

For some pairs, they had to play around with different environments to “set the mood,” swapping out spacious flight cages for cozier colony boxes.

And it worked.

“The two biggest success stories of 2024 were that we successfully bred our focal species, yellow-banded bumble bees, through their entire lifecycle for the first time,” Woolaver said.

“[And] the first successful overwintering of yellow-banded bumble bees last winter allowed us to establish our first lab generation, doubling our mating successes and significantly increasing the number of young queens for overwintering to wake early spring and start their own colonies for future generations and future reintroductions.”

Although the first-of-its-kind experiment required careful planning, consideration, resources, and a decade of research, Woolaver hopes that their efforts inspire others to help bees in backyards across North America.

“Be aware that our native bumble bees really are in serious decline,” Woolaver noted, “so when cottagers see bumble bees pollinating plants in their gardens, they really are seeing something special.”"

-via GoodGoodGood, December 9, 2024

7K notes

·

View notes

Text

@onenicebugperday

Didn't manage to add this in a ask and had to cut a few minutes of it here also, but here's one of the bbees I reared this summer being born! They are born without the yellow pigment, which slowly spreads to the stripes within the first day of life. You can tell that the big sister that came to help by gnawing the opening in the comb a bit bigger is not that much older, maybe up to half a day max. They are virtually helpless and very docile and usually hide under the comb until their wings get their proper rigor and their legs gain rudimentary coordination. At this age they won't even sting. I can't recall the exact species here, and the options are almost impossible to ID reliably without DNA-analysis in the absence of drones, but I'm pretty sure this is a Bombus cryptarum nest. The workers in this nest are around the average size, but we also had nests where the workers were the same size as the queen and some that (sadly) only produced workers that were under half a centimeter long.

3K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Longhorn bee, Melissodes sp., Apidae

Photographed in Virginia by Judy Gallagher

553 notes

·

View notes

Text

a girl and her watermelon piece

11K notes

·

View notes

Text

Ground-nesting bee time! (Well, all the warm months are, but I see them mostly first thing in the spring before everything grows in.)

Unequal Cellophane Bee female in her nest (Colletes inaequalis)

March 13, 2024

Southeastern Pennsylvania

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

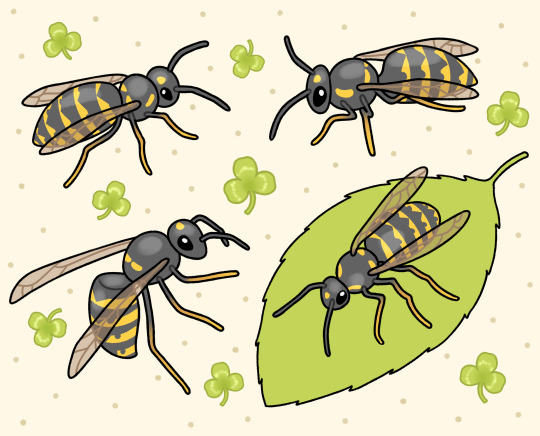

This is a Metaphycus wasp appreciation post.

I'm not sure if these are all different species, but they all have unique features. Wing stubs, half wings, full wings; white-tipped antennae, black-tipped antennae; chonky, longer; bright red, charred. All tiny, ♀️, ridiculous, and adorable. Enjoy. ❤️

644 notes

·

View notes

Photo

@icykali submitted: Wanted to submit a photo I took today that I’m really proud of, Black-and-yellow Nomad Bee on forget-me-not flowers! Found in the Hudson Valley, NY

You should be proud, it’s a beautiful photo! Good job :)

341 notes

·

View notes

Text

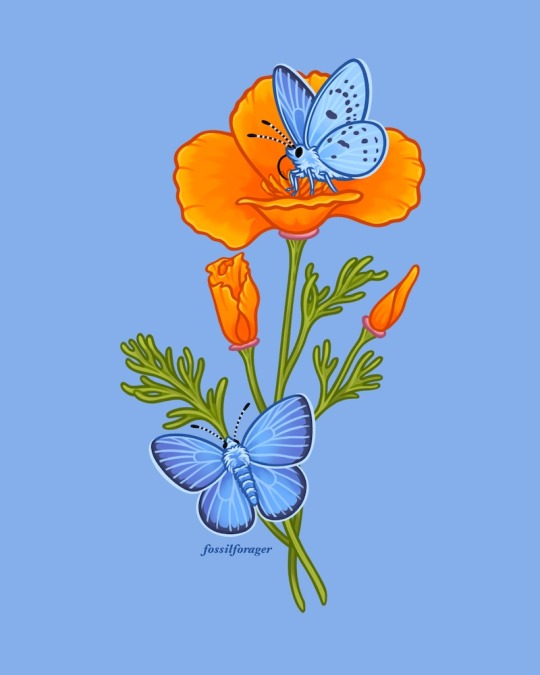

🦋 COMMISSIONS OPEN 🦋

I'm opening up some commission slots for April/May! If you're interested in getting custom work from me, check out the info and request a commission HERE.

🌿💕

281 notes

·

View notes

Text

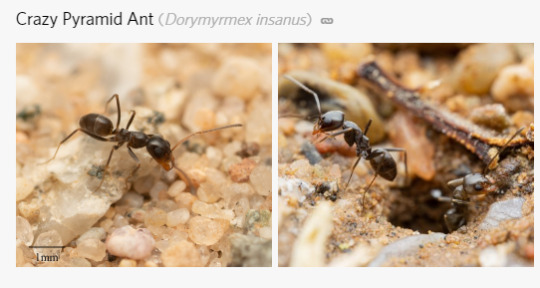

big fan of bug names that sound like they were given by the bug's bitter ex

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

tried painting with acryllics after thee longest time 🐝

180 notes

·

View notes

Text

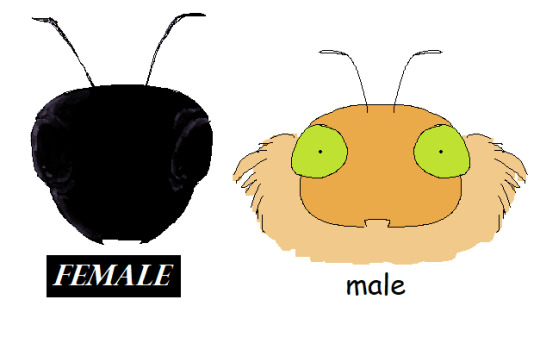

got my hands on a field guide of californian bugs and i found that there's this one bee species in southern california that looks like this

(Actual bugs under the cut, CW for insects)

70K notes

·

View notes

Text

November 5th, 2023

Wool Carder Bee (Anthidium manicatum)

Distribution: Native to Europe, Asia and North Africa; introduced to South America, North America, New Zealand and the Canary Islands, where it's invasive.

Habitat: Normally found in gardens, fields and meadows that contain their preferred plants, but also found in heathlands, woodland rides and clearings, wetlands, river banks,

Diet: Generalists; feed on the pollen from various flower families, with a preference for species found in their native distribution; prefer blue flowers with long throats.

Description: The wool carder bee earns its name from its behaviour of scraping the trichomes (or hairs) from the leaves of plants, creating little balls of hair that they use to line their nests, built into pre-existing cavities such as hollow stems and dead wood. Other materials used in nest-building include mud, resin, stones and leaves. The trichome bundles are fashioned into little cells, in which the female will lay an egg, along with a bundle of pollen and nectar for the larva to feed on after it hatches. Once all the cells are full, the cavity is sealed off with a terminal plug.

Male wool carder bees are extremely territorial and aggressive, both to other males of their species as well as other pollinators. This has two purposes: first of all, the male defends its ressources, which allows it to have ample food for itself, but a food-filled territory also attracts females for the males to mate with. When an uninvited guest comes to feed on a flower in the male's territory, the male will attack it with brief, aggressive tackles in order to shoo it away. If this isn't enough, the male will occasionally crush the enemy to death against its spiky abdomen (because this bee does not have a stinger!).

Here's a really cool video of a female wool carder bee harvesting trichomes!

(Images by Bruce Marlin and Pierre Bornand)

70 notes

·

View notes

Text

October 30th, 2023

Four-Toothed Mason Wasp (Monobia quadridens)

Distribution: Found throughout eastern North America, from southern Canada down to Mexico.

Habitat: Usually nests in wood borings or dirt banks; also occasionally takes over the nests of carpenter bees, ground bees and mud daubers. Prefers meadows and woodlands.

Diet: Adults feed on nectar; larvae feed on caterpillars.

Description: The four-toothed mason wasp is a non-aggressive, solitary potter wasp, though it's often mistaken for the more aggressive bald-faced hornet, sporting a similar size and color. Because of its solitary nature, however, the four-toothed mason wasp doesn't have a colony to ferociously defend like the bald-faced hornet does; for this reason, it only tends to sting when provoked.

Though adults are herbivores, larvae feed mainly on caterpillars. After a female wasp builds her nest, composed of small cells built into abandoned holes (such as the nests of other bees and wasps) or hollowed-out stems and tree branches, she will lay one fertilized egg per cell. Then, she will hunt for caterpillars, which she paralyzes with her sting, before bringing them back to store away with her eggs. Once hatched, the larvae have everything they need to grow and pupate, all within the same cell, before finally emerging as adults.

(Images by Sandy Rae and Eric R. Eaton)

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

Agaonids are so weird, but awesome! Pleistodontes sp. (a.k.a. fig wasps)

361 notes

·

View notes