Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Getting a Grip on Cultural Heritage Sites

A green door opens on an old street in the city of Groningen, the Netherlands, and a black and pink racing bike is wheeled out by a student named Cato. Outside, two gentlemen are waiting for her, her older brother and her boyfriend. Together, they will go on a long bike ride through the local countryside with a clear aim in mind. Cato asks the guys if they are ready to go and with that they all step on their sports bikes and start riding south. The weather is pleasantly warm and the wind not too harsh, perfect cycling conditions.

With the sun on her face, Cato thinks back to the Netflix show she was just watching, ‘La Casa de Papel���. The newest season has just dropped and she is very excited to start watching again, as the themes are so intriguing to her. It is a story about criminals who rob a bank and try to get away with doing so. The show plays with Cato’s emotions as she notices that even though she feels extremely bad for the hostages of the bank, she is rooting for the robbers and what they stand for. She loves the types of stories that make you look at things from a different perspective. Cato reminds herself that even though she loves watching the show, it would be harrowing to be in such a situation herself and that freedom is so important. However, the desire for freedom is also why the robbers in ‘La Casa de Papel’ started the crime. Sometimes, things like right and wrong are not as black and white as she would like and things are more complex.

Beautiful countryside surrounds Cato and while she looks around she thinks back to the last (guest) lecture that she had, about the train hijacking of 1977 in the Punt. About fifty people were held hostage by nine members of the Moluccan community for twenty days, this is another case where Cato finds it difficult to think of the hijackers as just the bad guys. Even though she thinks the crime is despicable, the Dutch government did not live up to their promises (to give them their own country) and have the Moluccans live in poor conditions for 25 years. She understands that people got angry about that and that they wanted to do something about it.

Cato has arrived in the small town of ‘the Punt’, and rides around for a little bit. There is no evidence in this town that something horrible happened close to the town. After the near 20km cycle ride, she is due for a break and sits down at a picnic table just outside of the town. Cato wonders why she was not able to find any reference to the horrible events and while doing so she can hear the words from a text she read about this from González in her mind: “heritage is presented as a neutral concept loaded with positive or negative meaning depending on whether the official or unofficial heritage of the oppressed is concerned” (p.21). She wonders if the reason that it is invisible is because of the negative or positive meaning the heritage site may hold for the people, and having the site be heritage is too complex, so not having any evidence might be easier.

Now fueled by dark chocolate and some water, Cato starts a new journey, to the train tracks where it happened. Unfortunately, she is unable to find direct coordinates and decides to go to the closest train track to the Punt. After a walk through the field that connects the road with the tracks, she is looking at an empty train track, just like any she has seen before. She sees no evidence of any event taking place there. She considers crossing the tracks as the guest lecturer said that there are bullet holes in one of the poles, but decides against it due to fear of trains/death. She stands in front of the tracks for a while and thinks about the horrors that took place years prior, but notices that it is hard to do so because there is no evidence left. So, she leaves.

Cato starts her journey back home, now fueled by annoyance that the hijacking events seem to be erased from the past and that there is no place where one can reflect on the incident. Using Garden’s notion of the heritagescape that she had to read for one of her courses, Cato starts to plan a way to manifest a heritage site at the Punt. She thinks it is so important to make the train tracks a heritage site because “The lack of a full appreciation of the heritage site as a place will also have serious repercussions because without this it will remain difficult to break down the heritage site and examine its constituent parts” (396). In her mind, Cato goes through the basic aspects that a heritage site should have by Garden: “(i) how the individual site operates and portrays the past, (ii) how one (or more) site(s) operate relative to another and finally (iii) lead to a better understanding of the heritage site as a larger concept and as a cultural phenomenon” (397). Using this, Cato thinks it would be best to make the walk from the road up to the train tracks an outdoor museum with information boards placed along the way. This way, there is information for those interested in read without disturbing its nature too much. She thinks it is important to have information, stories, and background knowledge about the hijacking to open the space for both communities. Mainly, Cato thinks it is crucial for something to be done, as otherwise history would be forgotten... and that is a true crime.

After all of this pondering, Cato has finished the long cycle and has arrived home. She and her bike go inside and the green door closes.

Works Cited

Garden, Mary-Catherine E. “The Heritagescape: Looking at Landscapes of the Past,”

González, Pablo Alonso. "The Emergence of Heritage." In The Heritage Machine: Fetishism and Domination in Maragateria, Spain, 17-67. London: Pluto Press, 2019. Accessed June 3, 2020. doi:10.2307/j.ctv86dhrk.6.

Hans Peters (ANEFO). Nationaal Archief, Den Haag, Rijksfotoarchief: Fotocollectie Algemeen Nederlands Fotopersbureau (ANEFO), 1945-1989 - negatiefstroken zwart/wit, nummer toegang 2.24.01.05, bestanddeelnummer 929-2101

International Journal of Heritage Studies 12, no. 5 (2006):394-411.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Meme-mystifying Frisia

Where our journey began…

[Translations: 1st Picture ‘My piece of Sugarbread’, ‘Dad’ (taking the last piece), 2nd: ‘Crying’, 3rd: ‘Nice bite’, 4th: ‘Groninger: *speaks with an accent*, What I hear: whla whla whla whla’]

As you all already know, it’s a bit of a strange situation we are all in at the moment, in a time of social distancing, it seems we have to come up with new ways to keep ourselves occupied. If there is one thing that can get us all through and keep us entertained... it’s gotta be memes, and for the Frisians it’s no different!

These days it’s difficult for many Frisians to experience their ‘Frisianness’ in a group setting or in person, but on online platforms such as Instagram, this is still possible. Pages like Omrop Fryslân or ‘FryslânMemelân’ can create a shared experience, even if you are sitting at home by yourself.

Instagram pages like these can be seen as online mediations of Heritage. It allow for cultures to showcase their shared heritage.[1] The Omrop Fryslân page consists of a variety of different posts expressing ‘Frisianness’ daily, there is information about what is happening in the province, decade old tales of Fryslân and Frisians, as well as light hearted videos and memes to allow the reader a little respite, particularly in times like these. It allows for Frisians to experience their shared heritage on an online platform; but also allows ‘non-Frisians’ to experience, even just for a few minutes, what it must be like to be a Frisian.

Omrop Fryslan is the regional Frisian radio broadcaster with a mainly older audience of listeners, as most young people tend not to listen to the radio, their Instagram page is catered towards a younger audience. Whether it’s complaining about your Dad taking the last bit of Sûkerbôle, or insulting Groningers, it seems there’s a strong community feeling of what it means to be Frisian, particularly for younger Frisians who may only speak the language with their immediate families.

What Katie found when looking through the comments of some of the posts, is the banter and jokes shared between Frisians, who otherwise probably would never have met. There is a connection the audience has with each other through their shared Heritage and language.

[Translation: 1st: ‘A new day, by Frisian band the Kast’, 2nd: ‘When I express myself in Frisian, vs when I express myself in Dutch/ABN’, 3rd: ‘When your girl leaves you for a Groninger, rough translation:‘crap’, 4th: A Hollander waiting for confirmation that Frisian is a dialect’]

Sites like these ‘remystify’ the idea of what it means to be Frisian, as Cato noticed, Fryslân is stereotypically seen as a province of farmers, and the language is seen as only spoken by the elderly in rural villages. Although the memes often live up to this stereotype with humour, joking about the farmer lifestyle and fierljeppen (pole jumping), these memes in fact are evidence in itself that it is not a culture of the past, but it is very much modern and thriving.

As Professor Jensma mentions in ‘Remystifying Frisia’. There is a remystification of Frisian culture taking place today. Jensma refers to physical experiences such as authentic trips to Frisian farms or bands like Baldrs Draumar singing tales of the glorious Frisian past; these are all examples of experiencing ‘Frisianness’ as a historical and mythical concept[2]. We would argue that Frisian memes and gifs provide another form of experience in what it means to be Frisian… Is it authentic? That’s another question. Will such a tag as ‘authentic Frisian memes’ exist in decades or centuries to come? Who knows.

In the evermore connected world we live in, it is easy for peripheral cultures to cling to nationalistic ideologies and retrench themselves into their heritage. Here this is not the case, pages like these have ‘moved with the times’ so to speak. This in turn helps change stereotypes young Frisians may have of their province, as well as change misconceptions from those who are from other areas of the Netherlands looking in. It is a mediation of heritage between insiders and outsiders (Like a local and a tourist).

Furthermore, Emma found that, as Frisian is more an oral language than a written language, these platforms expose young people to Frisian in its written form, and to the Frisian ‘slang’. Frisian children have limited experience learning Frisian in schools, and many leave school without having learned even basic reading and writing skills[3]. Unlike being in classes learning the Frisian spelling and grammar, or reading Frisian literature books written by old men, ‘Fryske memes en gifkes’ shows a funnier, cooler and younger language.

An online presence for minority languages and cultures is of paramount importance in upholding a shared sense of community and heritage, it has also allowed a language to redefine itself. The number of Frisians who could also write in Frisian has risen from 17% (in 1994) to 29% in 2011! All thanks to these social media platforms.[4]

Instagram pages like Omrop Fryslân allow Frisians to experience their ‘Frisianess’ in an online setting, particularly for those who have moved out of the province or the country, and now more than ever before, it allows Frisians in Fryslân to experience their Frisianness from home. For a minority language with the reputation of being spoken by farmers and village folk, these platforms show a younger, more digital and developed concept of ‘Frisianness’, . It is an online community consisting of 51.9k followers, all coming together to experience their shared cultural heritage.

If you’re interested in looking for yourself:

https://www.instagram.com/omropfryslan/ https://www.instagram.com/fryslanmemelan/

I think it’s safe to say, this journey down our Instagram feed has been an interesting one, can you think of any other examples of heritage mediation on Instagram or other social media platforms? What do they mean to you? We’d love to hear what you think!

Until the next time!

Katie, Cato and Emma

[1] Jensen, B. (2014). Instagram in the photo archives curation, participation, and documentation through social media. Arxius i Industries Culturals, 1-10.

[2] Jensma, Goffe: “Remystifying Frisia. Experience Economy along the Waddensea Coast”.

[3] Soad Friezen kinne net goed lêze en skriuwe, (2015, November 11), www.omropfryslan.nl Retrieved from https://www.omropfryslan.nl/nijs/587465-soad-friezen-kinne-net-goed-leze-en-skriuwe

[4] van der Meer, C. (2012). New media for multilingualism: Practice and Research Questions. Final report EUNoM: European Universities on Multilingualism project.

0 notes

Text

The Advice Giving Journey

What a strange time we live in! Everything is closed, we’re stuck indoors, and spending an ungodly amount of time on the internet. While we’re all boarded up inside, everything around us has come to a halt. Local institutions are suffering unless they can modernise overnight. Desperate for advice, Het MOW Museum Bellingwolde approached us asking for advice on how they can effectively amplify their online presence.

Having spent weeks reading articles and buffing up their knowledge of heritage mediation mechanisms, Group 3 stepped up to the challenge determined to help. To aid their efforts, the museum provided an information document and held a Q&A session.

Initially we encountered a problem; the average visitor to the museum is “a female in her 60s from the surrounding area”. Excuse the generalisation, but the average tech-savvy internet user is from a much younger demographic. How can we ensure they don’t lose the bulk of their audience while also making it accessible to younger generations? To find a solution we looked at other museums which have successfully created an online presence. According to Silberman there is a “need to find some mechanisms for enabling the local community to participate in the heritage nomination process” (2012, p.17) therefore we suggested it would be effective to create a forum-like feature beneath each artwork’s entry. Perhaps the museum can ask virtual visitors questions to encourage discourse. As soon as the experience can be personalised, participants will create a bond; “As museum audiences demand increasingly more interaction, museums are devoting areas of their Web site to information that is specific to and relevant for them, enabling not only focal relationships between organisation and audience (one-to-one and one-to-many) but also multilateral relationships (many-to-many) between organisations and audiences, among members of a single audience and among various audiences” (Camarero et al 2016, p.44). Allowing people to freely comment and share instantly adds a more immersive layer of involvement. Naturally some moderation will be required on the Museum’s behalf; however, this should be completely doable with little effort.

The museum staff mentioned they have previously used Pinterest to put their foot in the virtual door. Although this may have been effective some years ago, it is no longer as widely a used platform as it used to be. It would be more useful to begin to tag the artefacts already on their own website to encourage traffic. This will help them become more visible on the Google search engine, while simultaneously making the site more user friendly as related artefacts can be suggested to viewers.

Bearing our academic and internet experience in mind, we formulated our policy advice. Originally it spanned an intimidating 5 pages so we whittled it down to it’s current far more manageable 3 page form before presenting it to the busy museum curators. What will the future hold for Het MOW Museum Bellingwolde? Google them, providing they took our advice you’ll find out!

Until next time!

Katie, Cato, Emma

Bibliography:

Camarero, Carmen, María José Garrido, and Rebeca San José. "Efficiency of Web Communication Strategies: The Case of Art Museums." International Journal of Arts. Management 18, no. 2 (2016): 42-62. Accessed May 11, 2020.

Lovre website https://www.louvre.fr/en/visites-en-ligne (last accessed 11/05/2020)

Mawere, Munyaradzi, and Genius Tevera. "Zimbabwean Museums in the Digital Age: A Quest to Increase Museum Visibility in Public Space through Social Media." In African Museums in the Making: Reflections on the Politics of Material and Public Culture in Zimbabwe, edited by Mawere Munyaradzi, Chiwaura Henry, and Thondhlana Thomas Panganayi, 247-68. Mankon, Bamenda: Langaa RPCIG, 2015. Accessed May 11, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctvh9vwmh.13. Silberman, Neil & Purser, Margaret. “Collective Memory as Affirmation: People-Centered Cultural Heritage in a Digital Age.” In Heritage and Social Media : Understanding heritage in a participatory culture edited by Elisa Giaccardi (London: Routledge, 2012): 13-29. www.jstor.org/stable/44989650

0 notes

Text

Food commodification, authentic or fake?

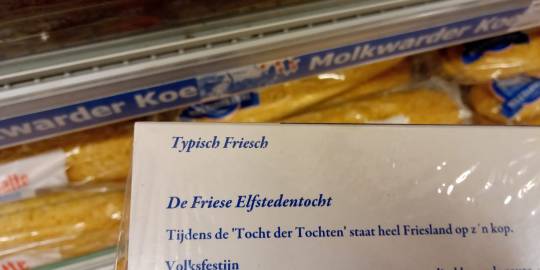

The topic of this blogpost is the cultural commodification of the local food varieties in Fryslân and Groningen.

You do not have to visit another country to witness the commodification of cultures and cultural objects. It is right in front of us, just go to your local Albert Heijn or Jumbo! The place of origin for each product is often proudly displayed on it’s packaging. You can’t buy some sugar bread without it being covered with the Frisian flag and the words ‘Echte Fryske sûkerbôle’ (“Real Frisian sugarbread”)

… or with ‘Groningse mosterd’ written in big font on the front, preferably also with the provincial flag of Groningen, to really get the message across.

There are even cases of almost identical products being sold next to each other. See here three variants of Droagewoarst/Drogeworst (“Dry sausage”) in the supermarket. Notice the price and packaging differences. Interestingly only the Groninger variant has an actual landmark of Groningen on it (De Martinitoren), the Frisian shows a skûtsje sailing ship (harking back to the stereotype of Frisians as seafarers), and the Drentse has an intimidating man for some reason.

As shown in Prentice’s ‘Experiential Cultural Tourism: Museums & the Marketing of the New Romanticism of evoked authenticity’ cultural consumers want to take part in an authentic cultural experience, and food is a competitive market. Like museums and other cultural experiences, food suppliers and companies are in constant competition with each other, they want that edge on their competitors, they want to provide the best cultural experience, and what better way to do this than by sticking the ‘authentic’ label on their products. Why are we compelled to go for the ‘authentic’ option over the non-branded standard oranjekoek?

Why is this appealing? Does the addition of flags on packaging give the impression of extra authenticity? What is ‘real’, and what does this word really mean? We see again and again the questioning of authenticity in cultural heritage; food and drink is not exempt from this. This commodification of local foods is everywhere, but what is the reasoning behind this? What are the effects, if any, of this commodification?

The magnification, or arguably exaggeration of the cultural and local significance of these foods (shown through packaging), is arguably down to one thing and one thing only. Money. Putting the word ‘echte Fryske [...]’ (“real Frisian”), or ‘pure’, ‘authentic’, ‘original’ gives the product an air of legitimacy. People want to pay that extra bit of money for the real deal, food suppliers notice this. Does it say something about the human condition that we feel more satisfied to part with our hard earned cash when the persuasion that we’re being more authentic is implied?

What we want to know is, what are the implications of the commodification of Frisian and Groningse foods, if there are any…

Well, according to Phillip Felfan Xie, this commodification does not ruin the value of the original product, it enables the reinventing and strengthening of identities (in this case, regional Dutch identities). It can be argued that an empowerment of local cultures is created through the commercialisation of unique products. However, as Comaroff and Comaroff would argue, they are taking something from their own cultures to sell for material empowerment.

Clearly, there are differing opinions as to what cultural commodification is and its effects. Comaroff and Comaroff go on to conclude, in their book Ethnicity.inc, that commodification in this way, changes the quality and value of the product.

Though, maybe this commodification is just a way for Frisians and Groningers to display their identity and show off, so to speak, their pride for their province, culture and their gastronomy. A competition develops not only between supermarket suppliers, but also between provinces. Ultimately the decision of who was the inventor can create a friendly rivalry between cultures. For example, the eierbal is certainly Gronings, right? So why do the Scotish get away with claiming ownership of the ‘Scotch Egg’, an identical concept? If brands sell better with a Frisian flag plastered on it than they do with a Groningen flag, does that mean the Frisians are better than the Groningers? Look here how even the Groningen dry sausage has a pompebled and Frisian sign of quality on it:

Something else to consider is whether the addition of labels actually suggests a better quality product or not. Do these labels cater to our illusion of obtaining cultural capital? If that is the case then it could be suggested the products being sold do not necessarily have any authenticity at all. They are just as mass produced as their shelf neighbours; only they are given an extra special treatment by consumers because of their branding. Professor in Frisian culture Goffe Jensma suggests “the sensibility of consumers is no longer aimed at the availability, the costs, or the quality of the products, [...] but on the experience of authenticity as part and product of the ‘experience economy’ instead. Experience itself has become a commodity.”[1] Supporting the local economy gives us a sense of benevolence and philanthropy. We enjoy products more with this added sense of importance.

Through this commodification of local foods, we must consider what makes food ‘authentic’, and what makes it just an ordinary, dare we say fake, product? Here’s a clip to demonstrate how you can be tricked by packaging

youtube

Some food for thought:

We hope this blogpost got you thinking, but what we want to know is: What other examples of food commodification can you think of from your culture(s)? What would you say makes food ‘authentic’? Is commodification really a big deal with local foods? Is there such a thing as ‘echte’ fryske sûkerbôle (Real Frisian sugarbread)?

Talking about all this food is making us all hungry… until the next time!

- Emma, Katie and Cato

(Packaging products in the bakery in Frisian flag wrapping paper; all images and video from Katie, Emma and Cato).

Footnotes:

[1] Goffe Jensma, Remystifying Frisia: Experience Economy along the Waddensea Coast. Page 1.

Bibliography:

Prentice, Richard. “Experiential Cultural Tourism: Museums & the Marketing of the New Romanticism of Evoked Authenticity,” Museum Management and Curatorship 19, no. 1. 2001.

Jensma, Goffe: “Remystifying Frisia. Experience Economy along the Waddensea Coast”.

Silberman, Neil & Purser, Margaret. “Collective Memory as Affirmation: People-Centered Cultural Heritage in a Digital Age.” In Heritage and Social Media : Understanding heritage in a participatory culture edited by Elisa Giaccardi. London: Routledge, 2012.

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cultural memory: the doorknob to our history?

21st February 2020

If you take a walk around the city you live in, do you think about all its history? Do you look at a church and wonder about all the things it has seen? Do you ever wonder about those who have walked the same path before you? Today, this blogpost will introduce you to some of the hidden cultural history of beautiful Groningen. Even if you are a Stadjer, we might even teach you something new about your city!

If you have ever been to this small city in the northern part of the Netherlands, then you will know of the Martinitower at its centre. Did you know, however, that the iconic green bronze layers at the top of the tower were only added after a huge fire burnt down the original wooden layers?[1] Did you know the surrounding buildings to the south-east of the Martinitower were demolished after World War II? Well we’ve got news for you, they did… and not for the reasons you may think. The Nazi-German troopers stationed in Groningen during the War did unimaginable, despicable things in those buildings. For those reasons, after the war, the citizens of Groningen wished for these events to be forgotten and erased from memory.

When you walk from the Grote Markt and through the Vismarkt, you will see the ‘Der Aa kerk’. Apart from its beauty, it also holds a rich history. During the War, many Jewish citizens of Groningen were sheltered in the attic of the church.[2] This was done to prevent them being deported and put into concentration camps by the Nazis. Because of this, many survived the war. However, from the 3,000 Jewish citizens living in Groningen before the War, only 180 survived.

You may be wondering why you are being given all this information, but hang in there, everything is relevant to what we want to discuss in the remainder of the blogpost. Finally, we need to discuss one last case of (not so) hidden history in the city centre of Groningen. This time it brings us to the busy, colourful and beautiful street of the Folkingestraat. This street used to be the centre of the Jewish district of Groningen, but after the War, there was not much left of the Jewish community that once occupied it. Therefore, it lost its identity as the Jewish sector of Groningen and began to be occupied by the general public.[3]

To ensure that the history of the street would not be lost, in 1997 the municipality decided that expressive representations of the former Jewish community should be placed there in their honour. This would be what Dołowy-Rybińska would call ‘Constructing a symbolic landscape’.[4]

Throughout the street, now placed are small hints to its past; moons that go from crescent to waning, portraying the rise and downfall of the community. The door without a doorknob, symbolically representing the history of the Jewish community, a history permanently closed and locked away in memory.[5]

Keeping the topic of cultural memory of the Folkingestraat in mind, the remainder of this blogpost will discuss the academic papers by Pierre Nora “Between Memory and History: Les Lieux de Mémoire” and “The Europe of Minorities: Cultural Landscapes and Ethnic Boundaries” by Nicole Dołowy-Rybińska, in relation to the case study that has been presented to you.

Rybinska claims that “the visual presence of minority languages and cultures in a specific territory create sharper ethnic boundaries,”[6] although, that is not the case in Folkingestraat. The symbolic references to the Jews who lived here in the past are very subtle and honestly unnoticeable to any unknowing members of the public who walk down the street, they might only remark at the strange sight of a portrait of a horse’s rear end on a wall (see above). In an otherwise Dutch city, “the [Jewish] minority takes possession of the territory by marking it in a visible way through its language and signs,”[7] the Jewish community of the past is marking its territory, so despite the fact the Jewish community no longer live there, their memory and spirit dwell.

According to Nora, memory is “nothing more [...] than sifted and sorted historical traces;”[8] so how do we decide what to remember? By immortalising the Jewish diaspora in Groningen with these displays, those with the funds have decided that that aspect of Groningen culture was worth remembering. When the Jews were being evacuated during the German occupation, surely they did not believe that there should be any traces of them living here, the collective memory is shifted. This begs the question whether collective memory is dictated by those in power, or perhaps those with wealth and social standing? Naturally these things change over time and therefore subtle symbolic reminders of a community may be more effective than concrete representations, as these are less likely to offend those who do not understand or notice them.

To wrap everything up, the Folkingestraat is an example of honouring and remembering the past, and the Jewish minority previously present in the area. The memory of the Jewish community is celebrated on the street, with public images and artworks. It can also be a means for the Jewish population of Groningen to ‘re-establish or to re-construct from scratch their cultural identity in the territories they inhabited’.[9]

It is clear we choose to commemorate the aspects of our cultural heritage we wish to commemorate. In Groningen we remember the Jewish community who lived in the Folkingestraat and their experiences during WWII. However, we choose to erase the memories of the German occupation. Of course, the Nazi regime should not be celebrated or commemorated, and it is understandable that the population of Groningen after the war wanted all traces of the occupation to be wiped from memory, but would there be benefits to keeping the buildings? Would it not serve the purpose of education? Reminding people of what happened and to ensure history does not repeat itself?

So, here is some food for thought: Do you think all aspects of cultural heritage, good or bad, should be remembered? Is cultural heritage only meant to include the important, morally acceptable things? Or are there some part of our heritage best left in a history book?

Until the next time! ~ Katie, Cato and Emma

[All pictures are from the personal archive of Cato Piek]

Footnotes

[1] Yuri Visser, “Geschiedenis Van De Martinitoren in Groningen.”, Historiek, 2014.

https://historiek.net/geschiedenis-van-de-martinitoren-in-groningen/41972/.

[2] Bert Deelman, Onderduikersplek Der Aa kerk - Groningen - TracesOfWar.nl. Accessed February 20, 2020. https://www.tracesofwar.nl/sights/64356/Onderduikersplek-Der-Aa-kerk.htm.

[3] (van Dam, A. De Folkingestraatbewoners Tussen De Beide Oorlogen. Stichting Folkingestraat Synagoge, 1977.)

[4] Nicole Dołowy-Rybińska, "The Europe Of Minorities: Cultural Landscapes And Ethnic Boundaries", Art Inquiry. Recherches Sur Les Arts 15, no. 24 (2013): 135.

[5] Regina Duvekot-Lammerts, Marjon Vischjager-Koster, T.K. Hoving, Ruud Haan, J. Elswijk, Ria Bollegraaf, Blaffertje, et al. “Groningen Centrum - De Joodse Folkingestraat.” FocusGroningen, May 2, 2018. https://www.focusgroningen.nl/groningen-centrum-de-joodse-folkingestraat/.

[6] Nicole Dołowy-Rybińska, "The Europe Of Minorities: Cultural Landscapes And Ethnic Boundaries", Art Inquiry. Recherches Sur Les Arts 15, no. 24 (2013): 125.

[7] Ibid, 132.

[8] Pierre Nora, "Between Memory And History: Les Lieux De Memoire", Representations 26, no. 1 (1989): 8, doi:10.1525/rep.1989.26.1.99p0274v.

[9] Nicole Dołowy-Rybińska, "The Europe Of Minorities: Cultural Landscapes And Ethnic Boundaries", Art Inquiry. Recherches Sur Les Arts 15, no. 24 (2013): 128.

Bibliography

Deelman, Bert. Onderduikersplek Der Aa kerk - Groningen - TracesOfWar.nl. Accessed February 20, 2020. https://www.tracesofwar.nl/sights/64356/Onderduikersplek-Der-Aa-kerk.htm.

Dołowy-Rybińska, Nicole. "The Europe Of Minorities: Cultural Landscapes And Ethnic Boundaries". Art Inquiry. Recherches Sur Les Arts 15, no. 24 (2013): 125-137.

Duvekot-Lammerts, Regina, Marjon Vischjager-Koster, T.K. Hoving, Ruud Haan, J. Elswijk, Ria Bollegraaf, Blaffertje, et al. “Groningen Centrum - De Joodse Folkingestraat.” FocusGroningen, May 2, 2018. https://www.focusgroningen.nl/groningen-centrum-de-joodse-folkingestraat/.

Nora, Pierre. "Between Memory And History: Les Lieux De Memoire". Representations 26, no. 1 (1989): 7-24. doi:10.1525/rep.1989.26.1.99p0274v.

van Dam, A. De Folkingestraatbewoners Tussen De Beide Oorlogen. Stichting Folkingestraat Synagoge, 1977.

Visser, Yuri. “Geschiedenis Van De Martinitoren in Groningen.” Historiek, April 22, 2014. https://historiek.net/geschiedenis-van-de-martinitoren-in-groningen/41972/.

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cultural Heritage, or just a Mythunderstanding?

Groningen, 27th of August 2019

Tomorrow we all celebrate Bommen Berend here in Groningen. If you ask the ‘Stadjes’, the local citizens of the city, it is the day we celebrate that Groningen is free! However, it must make you wonder, what is it that we are free of and why do we still celebrate it? This is what this blog is all about.

Firstly, what is it really that we celebrate?

The year is 1672, the Netherlands is under attack from four different sides and so, the Bishop of Münster seizes his opportunity to capture our beautiful land. This Bishop, Bernhard von Galen, tried to take over the north of the Netherlands before in 1665, luckily, he failed.[1] During this fight, tried to overpower us with the use of heavy bombing, thus the name “Bommen Berend” (Bombing Berend) came about. Don’t you think it is odd that we celebrate our freedom with the name of our capturer? It would have made more sense to name this day after the person who stopped the capture. Maybe that is why it is also referred to as “Gronings Ontzet” (Relieved Groningen), which does make more sense. For the non-Groningers reading this, on the 28th of August, we celebrate this day with horse races, a fair, and a really big fireworks display.[2]

After this free history class, the question is, why do we still celebrate this stuff, and if we do not know the background, is it still part of our cultural heritage? Let’s talk about it.

Time is a strange concept; to come to terms with such an abstract theory, we enjoy making sense of the past, experiencing the present, and making a future. All around the earth, “every society has a relationship with its past”.[3] What we must understand about heritage is it is the inherently flawed version of history. There is usually a kernel of truth in that which is presented but let’s remember “time makes liars of us all,” meaning we like to exaggerate things for many reasons which is discussed below.[4] Perhaps the main reason we have a tendency to pollute the truth is that “exotic enigmas enrich heritage more than drab details,” reality can be boring![5] When you tell a story to your mates in the pub, they don’t ask for a bibliography. We hardly fact check as much as we should; more often than we’d like to admit, we blindly believe what we are told. Why then do people consciously lie about something as hefty as history?

When we remember things, we are already interpreting it. We remember that which affected us most emotionally. You wouldn’t remember buying milk at the shop, but you would remember finding a €5 note on the floor. Maybe to your friends that €5 note becomes a €10 note, then to their friends a €20 that flew into your hand miraculously. Stories are twisted. What separates heritage from history, is that the imperfections may be left in. The victor doesn’t write the history books, they write the signs at heritage parks.

Despite the wealth of knowledge available to us, we still prefer entertainment over dry facts. We also still allow for the misconceptions to become reality: “we see the heritageisation of a popular memorial artefact being presented within the context of contemporary agendas”.[6] Modern day scholars place their own ideology into their work as much as those trying to valourise certain political or religious movements of the past. This is not necessarily a negative thing if you can believe that “fiction is [...] not the opposite of fact but its complement, giving our lives a more lasting shape.”[7] It’s near impossible to find accurate and completely unbiased sources on any historical events, thus the question of authenticity is impossible to answer. For example, in the 19th Century it was very popular to paint anything foreign as exotic, especially in relation to anything coming from the far East. So even diverse cultures have views about others which are not based on novelty. We must also remember “the present tendency for nostalgia and finding solace in heritage is just the latest phase of a much longer trajectory”.[8] That trajectory being that the way of presenting our past is evolving with humanity as does every facet of our existence.

Heritage gets us excited, it’s usually far more relatable than dry history books. Our “national conscience” can be provoked and a sense of community instilled.[9] Naturally, that which is interesting can, and is, swiftly commercialised. Heritage has become a “contemporary product shaped from history.”[10] “The present selects an inheritance from an imagined past for current use and decides what should be passed on to an imagined future;” investors in heritage predict what the future generations will find interesting.[11] They are also concerned with filling their pockets, so it is not always the most loyal representation they present. This can be nicely compared with the “popularity and commercialism involved in the medieval pilgrim business.” As with modern day commercial cultural heritage sites “crowds, enthusiasm and money-spinning generated could be similarly huge, and the popular mediation of memory and identity, similarly genuine.”[12] People go to heritage sites as pilgrims would have; to gain a sense of culture and seek status amongst peers. For this gratification they travel, learn and spend money on ‘special’ topics which, unless sought, people would not have access to. It's to make them feel more important and give social credit. It becomes an excuse for egotism as well as advertisement to other members of that cultural group. Those who do not support the commercialisation might be met with excuses like ‘it’s your heritage! We need to preserve it!’. “Being clannish is essential; to group survival and well-being;” it’s necessary to have some pride in your past albeit local or ethnic. After all, “those who seek a past as sound as a bell forget that bells need built-in imperfections to bring out their all-important individual resonances.”[13]

Knowing all of this, I am getting ready for the horse races and I’ve made plans to go to the fair and watch the fireworks. Even though I am not celebrating the history, I am celebrating Groningen. It is one day of the year where we can focus just on our beautiful city and be grateful for it too.

As always, we end with some food for thought: Can there be cultural value in an event if you do not celebrate its history too?

See you next time! ~ Cato, Katie, Emma

Bibliography

"Bommen Berend En Het Gronings Ontzet (1672)". Historiek, 2019. https://historiek.net/gronings-ontzet-1672/8866/.

Bijzet, Erik. "De Deventer Buiten-Bergpoort En De Groninger Herepoort In De Tuin Van Het Rijksmuseum". Jstor.Org, 2007.http://www.jstor.org/stable/40383454.

Harvey, David C. Heritage Past And Heritage Presents: Temporality, Meaning And The Scope Of Heritage Studies. 4th ed. Reprint, International Journal of Heritage Studies, 2001.

Lowenthal, David. The Heritage Crusade And The Spoils Of History. Reprint, Cambridge, U.K.:Cambridge University Press, 2003.

Footnotes

[1] "Bommen Berend En Het Gronings Ontzet (1672)", Historiek, 2019,

https://historiek.net/gronings-ontzet-1672/8866/.

[2] Erik Bijzet, "De Deventer Buiten-Bergpoort En De Groninger Herepoort In De Tuin Van Het Rijksmuseum", Jstor.Org, 2007, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40383454.

[3] David C. Harvey, Heritage Past And Heritage Presents: Temporality, Meaning And The Scope Of Heritage Studies, 4th ed. (repr., International Journal of Heritage Studies, 2001), 146.

[4] David Lowenthal, The Heritage Crusade And The Spoils Of History (repr., Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 2003), 144.

[5] Ibid, 136.

[6] David C. Harvey, Heritage Past And Heritage Presents: Temporality, Meaning And The Scope Of Heritage Studies, 4th ed. (repr., International Journal of Heritage Studies, 2001), 334.

[7] David Lowenthal, The Heritage Crusade And The Spoils Of History (repr., Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 2003), 146.

[8] David C. Harvey, Heritage Past And Heritage Presents: Temporality, Meaning And The Scope Of Heritage Studies, 4th ed. (repr., International Journal of Heritage Studies, 2001), 337.

[9] Ibid, 328.

[10] Ibid, 327.

[11] Ibid, 324.

[12] Ibid, 332.

[13] David Lowenthal, The Heritage Crusade And The Spoils Of History (repr., Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 2003), 128.

15 notes

·

View notes