Photo

Japanese Illustration: Cherry blossoms along the river. Gaku Nakagawa. 2008

365 notes

·

View notes

Photo

SHIT YEAH MIRENA FOREVER MIRENA 4 PREZ

Good news: Mirena IUD and birth control implant users now get 1 extra year of pregnancy prevention!

If you’ve got a Mirena IUD or birth control implant, rejoice! New research has shown that these methods prevent pregnancy for 1 year longer than previously thought. This means that Mirena actually lasts for 6 years (up from 5), and both Implanon and Nexplanon implants last for 4 years (up from 3).

This change is ONLY for birth control implants and the Mirena IUD. The expiration time for all other types of IUDs stays the same:

Paragard (copper) IUD: 12 years

Liletta IUD: 3 years

Skyla IUD: 3 years

The new expiration date applies to anyone who currently has a Mirena IUD or birth control implant, as well as anyone who gets them in the future. So for example: if you got your Mirena IUD in 2012, it will prevent pregnancy until 2018 (6 years). If you get a Mirena IUD in 2016, it will prevent pregnancy until 2022.

As always, if you want to get pregnant or stop using your IUD or implant before the expiration date, your nurse or doctor can remove it at any time and your fertility will go back to normal.

A round of applause to the medical researchers for bringing us an extra year of pregnancy prevention!

-Kendall at Planned Parenthood

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

at this point i’ve accepted that the most asian representation i will ever get out of a hollywood movie is when there’s a dark scene and i can see my own blank reflection staring back at me from the laptop screen

61K notes

·

View notes

Photo

<3

The Wild and Tender Kingdom part 5

#tenderwheninslumber

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

chink with horrible follower ratio passing judgement has no career. what am I saying?

it took me a while cause i never check my messages, but now i remember you! you tried promoting your soundcloud in my asks and i wasn’t down, so instead you resorted to racist insults. good day, sir!

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

rewatching s1 for like the 100th time--at what point does all the brilliant animal sight gag stuff (eg the croc wearing crocs) get added? is it like, we need to have a croc wearing crocs, where can we fit this in? or do you start out by needing someone to guard the food and say let's do a crocodile--hey, he should wear crocs? or some kind of total afterthought, or something else entirely? thanks. love the show, my favorite of all time.

Hello! I am going to answer your question, and then I am going to talk a little bit about GENDER IN COMEDY, because this is my tumblr and I can talk about whatever I want!

The vast vast vast majority of the animal jokes on BoJack Horseman (specifically the visual gags) come from our brilliant supervising director Mike Hollingsworth (stufffedanimals on tumblr) and his team. Occasionally, we’ll write a joke like that into the script but I can promise you that your top ten favorite animal gags of the season came from the art and animation side of the show, not the writers room. Usually it happens more the second way you described— to take a couple examples from season 2, “Okay, we need to fill this hospital waiting room, what kind of animals would be in here?” or “Okay, we need some extras for this studio backlot, what would they be wearing?”

I don’t know for sure, but I would guess that the croc wearing crocs came from our head designer lisahanawalt. Lisa is in charge of all the character designs, so most of the clothing you see on the show comes straight from her brain. (One of the many things I love about working with Lisa is that T-Shirts With Dumb Things Written On Them sits squarely in the center of our Venn diagram of interests.)

NOW, it struck me that you referred to the craft services crocodile as a “he” in your question. The character, voiced by kulap Vilaysack, is a woman.

It’s possible that that was just a typo on your part, but I’m going to assume that it wasn’t because it helps me pivot into something I’ve been thinking about a lot over the last year, which is the tendency for comedy writers, and audiences, and writers, and audiences (because it’s a cycle) to view comedy characters as inherently male, unless there is something specifically female about them. (I would guess this is mostly a problem for male comedy writers and audiences, but not exclusively.)

Here’s an example from my own life: In one of the episodes from the first season (I think it’s 109), our storyboard artists drew a gag where a big droopy dog is standing on a street corner next to a businessman and the wind from a passing car blows the dog’s tongue and slobber onto the man’s face. When Lisa designed the characters she made both the dog and the businessperson women.

My first gut reaction to the designs was, “This feels weird.” I said to Lisa, “I feel like these characters should be guys.” She said, “Why?” I thought about it for a little bit, realized I didn’t have a good reason, and went back to her and said, “You’re right, let’s make them ladies.”

I am embarrassed to admit this conversation has happened between Lisa and me multiple times, about multiple characters.

The thinking comes from a place that the cleanest version of a joke has as few pieces as possible. For the dog joke, you have the thing where the tongue slobbers all over the businessperson, but if you also have a thing where both of them ladies, then that’s an additional thing and it muddies up the joke. The audience will think, “Why are those characters female? Is that part of the joke?” The underlying assumption there is that the default mode for any character is male, so to make the characters female is an additional detail on top of that. In case I’m not being a hundred percent clear, this thinking is stupid and wrong and self-perpetuating unless you actively work against it, and I’m proud to say I mostly don’t think this way anymore. Sometimes I still do, because this kind of stuff is baked into us by years of consuming media, but usually I’m able (with some help) to take a step back and not think this way, and one of the things I love about working with Lisa is she challenges these instincts in me.

I feel like I can confidently say that this isn’t just a me problem though— this kind of thing is everywhere. The LEGO Movie was my favorite movie of 2014, but it strikes me that the main character was male, because I feel like in our current culture, he HAD to be. The whole point of Emmett is that he’s the most boring average person in the world. It’s impossible to imagine a female character playing that role, because according to our pop culture, if she’s female she’s already SOMEthing, because she’s not male. The baseline is male. The average person is male.

You can see this all over but it’s weirdly prevalent in children’s entertainment. Why are almost all of the muppets dudes, except for Miss Piggy, who’s a parody of femininity? Why do all of the Despicable Me minions, genderless blobs, have boy names? I love the story (which I read on Wikipedia) that when the director of The Brave Little Toaster cast a woman to play the toaster, one of the guys on the crew was so mad he stormed out of the room. Because he thought the toaster was a man. A TOASTER. The character is a toaster.

I try to think about that when writing new characters— is there anything inherently gendered about what this character is doing? Or is it a toaster?

ASK ME QUESTIONS ABOUT BOJACK HORSEMAN.

26K notes

·

View notes

Photo

i love you, piph

30 of you will win 30 of the best sex toys on the planet. No big deal.

I’ve got everything here from vibrators to dildos to butt plugs to harnesses and prostate toys, gift cards for the indecisive and a porn membership for the pervs! Plus, more than half the prizes are available to my international readers!

Enter now!

2K notes

·

View notes

Note

I created Pop That Pussy Pop. soundcloud: howardblake

this is not a question also your creation sounds like a palindrome fail

0 notes

Text

The Meaning of Leaning*

In the weeks leading up to the publication of Sheryl Sandberg’s new book, Lean In, critics had plenty to say about the Facebook chief operating officer’s ideas about being a woman in the workplace—even though few had actually read the tome. Many of the resulting discussions bizarrely mischaracterized what Lean In was about, tossing around misleading headlines, inaccurate facts, and unfair assumptions.

As it turns out, not even a fairly average entry into the world of corporate advice books is immune from double standards.

Sandberg intersperses personal anecdotes from her remarkable career (a vice-presidency at Google, serving as the U.S. Treasury’s chief of staff during the Clinton administration) with observations, research, and pragmatic advice for how women can better achieve professional and personal success. She urges women to “lean in” to their careers, and to be “ambitious in any pursuit.” Lean In is competently written and blandly interesting, and it does repeat a great deal of familiar research—although it isn’t particularly harmful to be reminded of the challenges women face as they try to get ahead.

Intentionally or not, much of the book is a stark reminder of the many obstacles women face in the workplace. I cannot deny that parts of it resonated, particularly in Sandberg’s discussion about “impostor syndrome” and how women are less willing to take advantage of potential career opportunities unless they are wholly qualified.

But Sandberg is rigidly committed to the gender binary, and Lean In is exceedingly heteronormative. Professional women are largely defined in relation to professional men; Lean In’s loudest unspoken advice seems to dictate that women should embrace masculine qualities (self-confidence, risk-taking, aggression, etc.). Occasionally, this advice backfires, because it seems as if Sandberg is advocating, “If you want to succeed, be an asshole.” In addition, Sandberg generally assumes women will want to fulfill professional ambitions while also marrying a man and having children. Yes, she says, “Not all women want careers. Not all women want children. Not all women want both. I would never advocate that we should all have the same objectives.” But she adorably contradicts herself by placing every single parable within the context of heterosexual women who want wildly successful careers and a rounded-out nuclear family. Accepting that Sandberg is writing to a very specific audience, and has little to offer for those who don’t fall within that target demographic, makes enjoying the book a lot easier.

One of the main questions that has arisen in the wake of Lean In’s publication is whether or not Sandberg has a responsibility to women who don’t fall within her target demographic. In The New York Times, Jodi Kantor writes, “Even [Sandberg’s] advisers acknowledge the awkwardness of a woman with double Harvard degrees, dual stock riches (from Facebook and Google, where she also worked), a 9,000-square-foot house and a small army of household help urging less fortunate women to look inward and work harder.”

At times, the inescapable evidence of Sandberg’s fortune is grating. She casually discusses her mentor Larry Summers, working for the Treasury department, her doctor siblings, and her equally successful husband, David Goldberg. (SurveyMonkey, of which Goldberg is CEO, moved the company headquarters from Portland to the Bay Area so he could more fully commit to his family.) She gives the impression that her movement from one ideal situation to the next is easily replicable.

Sandberg’s life is so absurd a fairy tale, I began to think of Lean In as a snow globe, where a lovely little tableau was being nicely preserved for my delectation and irritation. I would not be so bold as to suggest she has it all, but I need to believe she is pretty damn close to whatever “having it all” might look like. Common sense dictates that it is not realistic to assume anyone could achieve Sandberg’s successes simply by “leaning in” and working harder—but that doesn’t mean Sandberg has nothing to offer, or that Lean In should be summarily dismissed.

Cultural critics can get a bit precious and condescending about marginalized groups. We refer to them reflexively, placing principles above actual people. In the debate over Lean In “working-class women” have been lumped into a vaguely defined group of women who work too hard for too little money. But very little consideration has been given to these women as actual people who live in the world, who maybe, just maybe, have ambitions, too, and who could probably be more effectively helped with something other than a frenzied debate about a corporate advice book.

There has been, unsurprisingly, significant pushback against the notion that leaning in is a reasonable option for working-class women, who are already stretched woefully thin. Sandberg is not oblivious to her privilege, noting: “I am fully aware that most women are not focused on changing social norms for the next generation but simply trying to get through each day. Forty percent of employed mothers lack sick days and vacation leave, and about 50 percent of employed mothers are unable to take time off to care for a sick child. Only about half of women receive any pay during maternity leave. These policies can have severe consequences; families with no access to paid family leave often go into debt and can fall into poverty. Part-time jobs with fluctuating schedules offer little chance to plan and often stop short of the forty-hour week that provides basic benefits.”

It would have been useful if Sandberg offered realistic advice about career management for women who are dealing with such circumstances. It would also be useful if we had flying cars. Assuming Sandberg’s advice is completely useless for working-class women is just as shortsighted as claiming her advice needs to be completely applicable to all women. And let’s be frank: If Sandberg chose to offer career advice for working-class women, a group she clearly knows little about, she would have been just as harshly criticized for overstepping her bounds.

The critical response to Lean In is not entirely misplaced, but it is emblematic of the dangers of public womanhood. Public women, and feminists in particular, have to be everything to everyone; when they aren’t, they are excoriated for their failure. In some ways, this is understandable. We have come far, but we have so much farther to go. We need so very much, and we hope women with a significant platform might be everything we need—a desperately untenable position. As Elizabeth Spiers notes in The Verge, “When’s the last time someone picked up a Jack Welch (or Warren Buffett, or even Donald Trump) bestseller and complained that it was unsympathetic to working class men who had to work multiple jobs to support their families? … And who reads a book by Jack Welch and defensively feels that they’re being told that they have to adopt Jack Welch’s lifestyle and professional choices or they are lesser human beings?”

Lean In cannot and should not be read literally, nor should it be read as a book offering universally applicable advice to all women, everywhere. Sandberg is confident and aggressive in her advice, but the reader is under no obligation to do everything she says. Perhaps we can consider Lean In for what it is—just one more reminder that the rules are always different for girls, no matter who they are, and no matter what they do.

* This review appears in Maura Magazine, issue 11. You should subscribe to Maura Magazine. It’s affordable and a great investment in a great publication.

120 notes

·

View notes

Quote

It gets easier. Everyday it gets a little easier. But you gotta do it everyday, that’s the hard part.

the Baboon runner in Bojack Horseman season 2. (via a-madness-shared)

damn that enlightening wise and suspiciously fit and calming baboon. damn him to the euphoric heaven from whence he transcended.

(via bojackhorseman)

854 notes

·

View notes

Photo

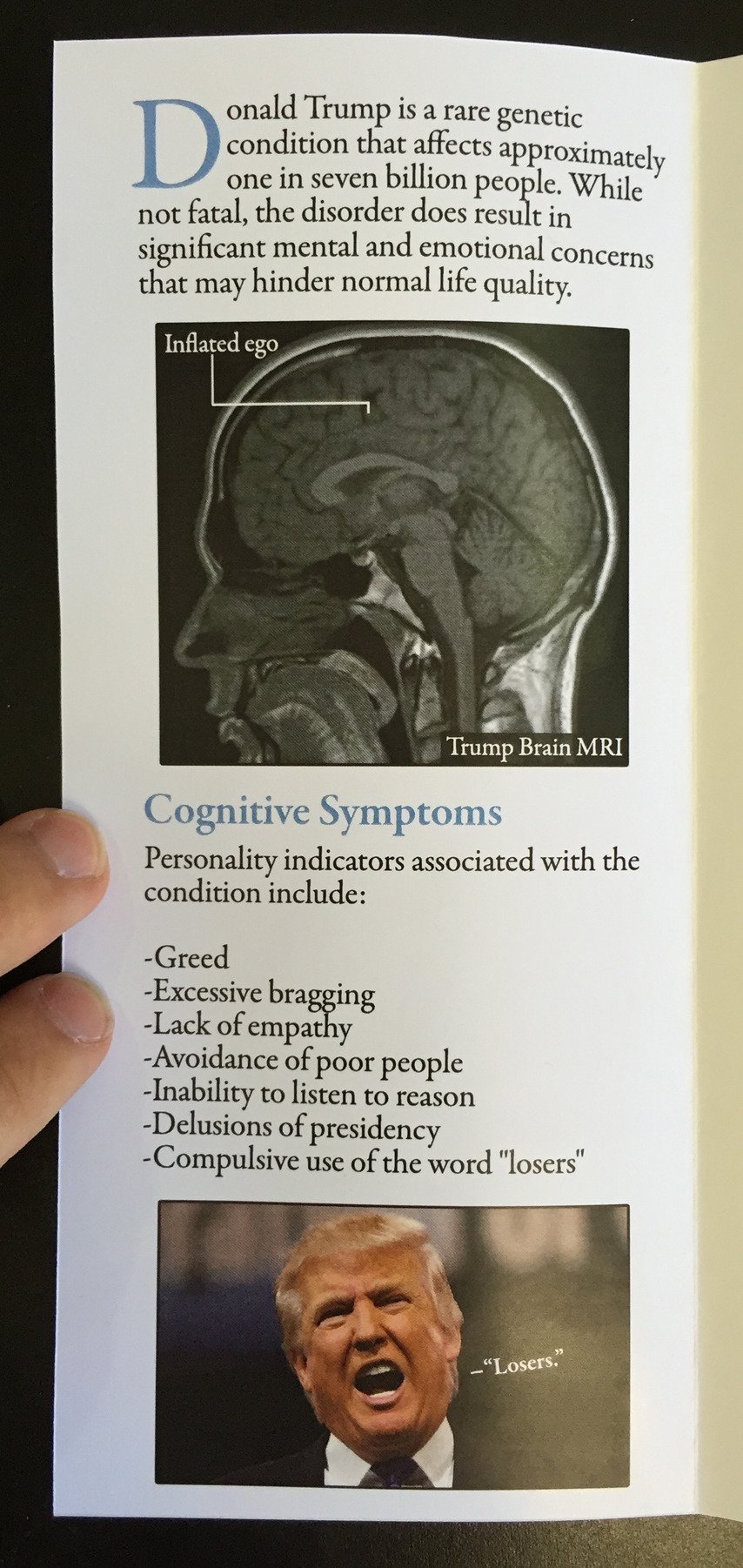

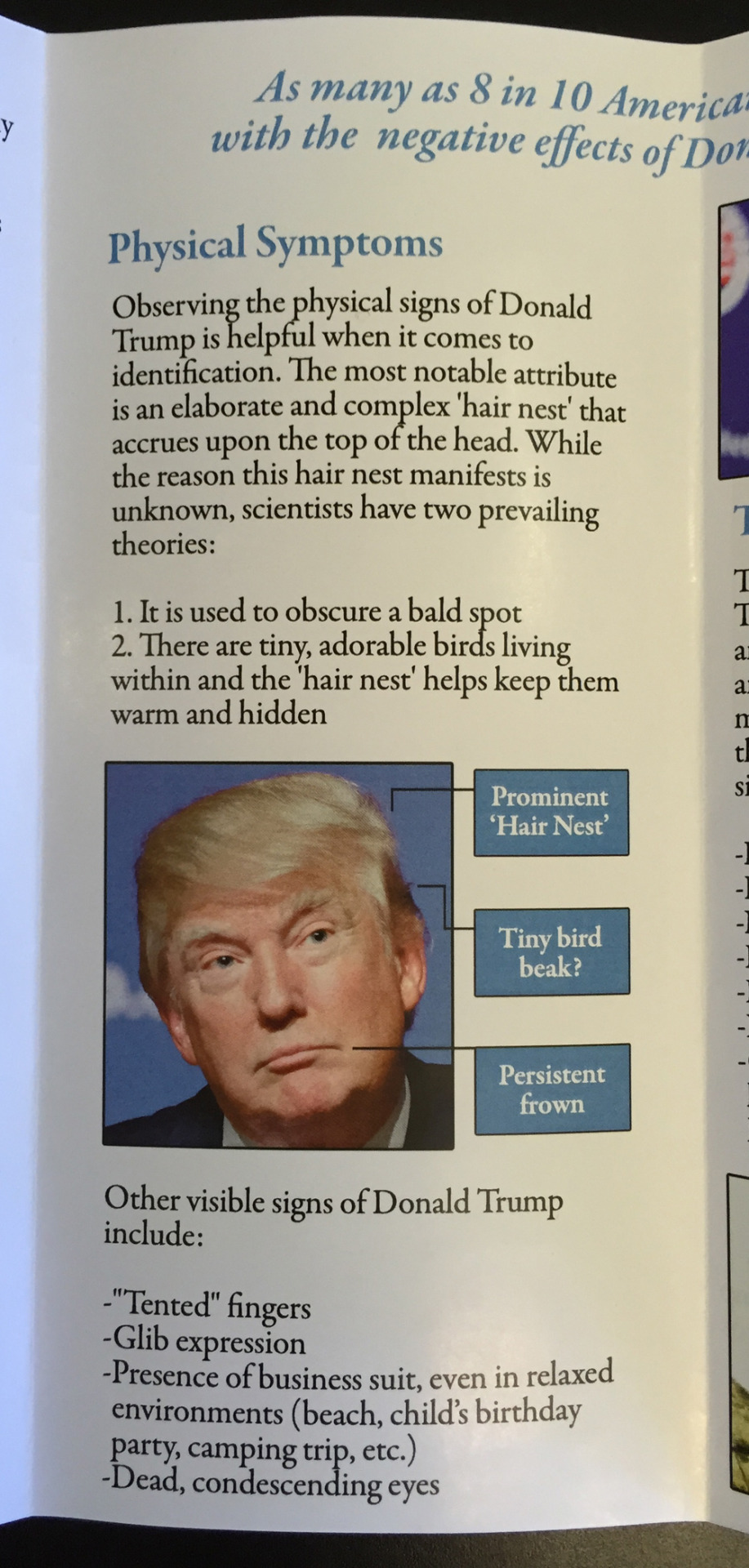

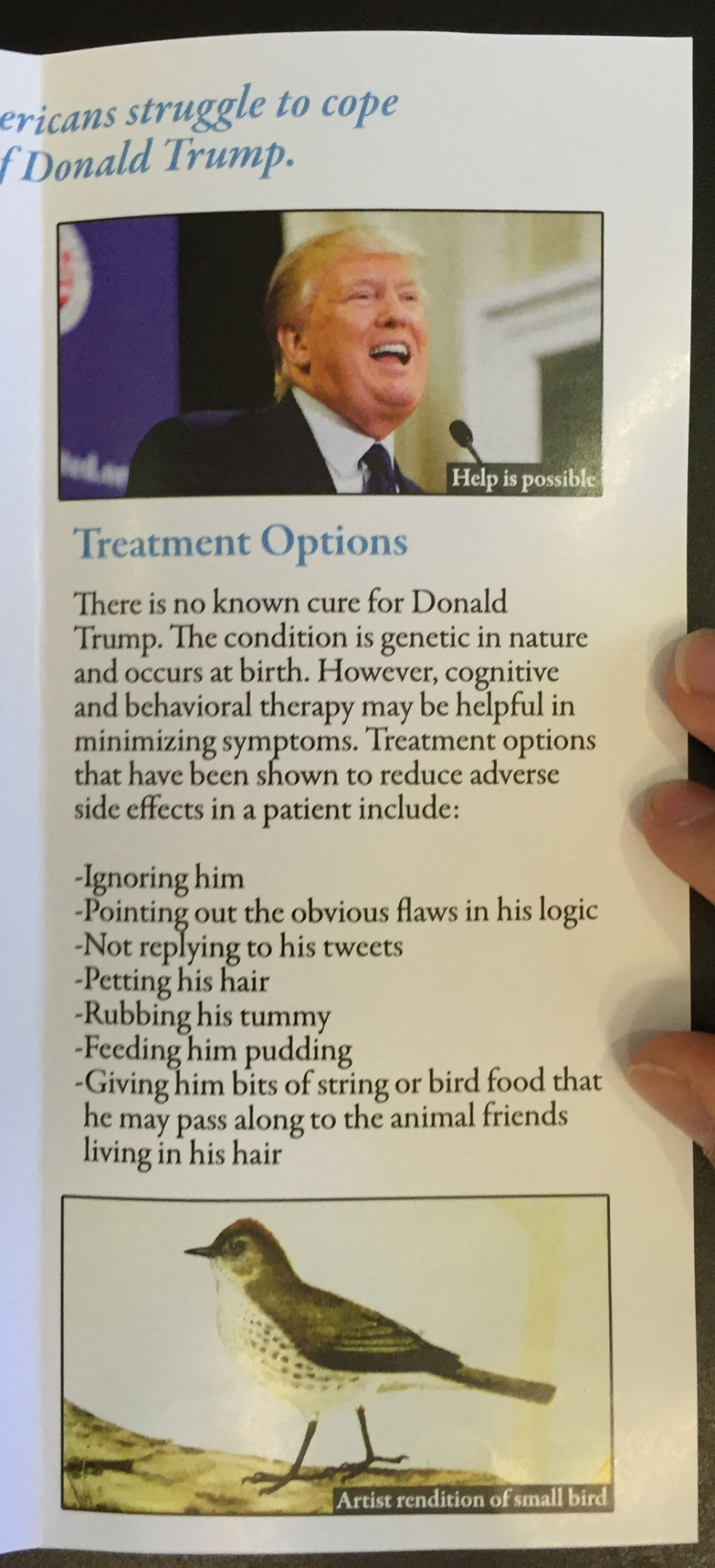

I added this fake health brochure about Donald Trump to a doctor’s waiting room

409K notes

·

View notes

Photo

This is a collection of anonymous essays by women talking about female orgasm.

One possible prompt was: Imagine you could give this essay to a past or future sexual partner, free of judgment or repercussion. What would you want them to know? A more general approach was to simply speak about your relationship to orgasm, whatever that means to you, in whatever way you wanted.

The female orgasm can sometimes be challenging to achieve and/or talk about, but it goes beyond that. When we talk about female orgasm, something deeper is at play—for one, the societal assessment and conversation of female sexuality; the consequences of which bleed into the areas of our lives far outside the bedroom. We wanted to start a dialogue about how women achieve sexual pleasure; something that is often ignored, devalued, or misunderstood.

We reached out to some friends. They reached out to some friends. They reached out to some friends��We slowly began to build a collective of women who had something to say. People began to immediately respond with intense affirmation and stories of their own. We felt such a rush from seeing a group of women opening up. It confirmed that this is something a lot of women are itching to talk about.

Here is our look into the spectrum of desire. Of frustration. Of experiences that have left an impact.

Getting to see this range of opinions and preferences and fears and fantasies has profoundly moved us. In making it public, we hope to offer that feeling to others and to encourage them to keep the discussion going in their own lives. This is just the beginning. Let’s start talking…

209 notes

·

View notes