Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

This week I wrapped up my work on the website for the newly titled Virginia Changemakers program, which I have been building for most of my internship. The website has individual pages for each of the Library of Virginia’s programs, which list the honorees alongside a downloadable poster corresponding to their program year. I also used a Geolocation plug-in to display all of the honorees on a map of Virginia, from which users can navigate to individual biography pages. I went through and ensured that all of the item entries are uniform so that they can be sorted properly into eras and themes by PHP scripts, and I’ve made changes to improve the way the biographies are displayed. I’ve worked both through the Omeka admin interface and by editing the server-side files to fulfil the goal of creating a usable resource for teachers and students. Below is the link to the site if anyone wants to check it out!

http://edu.lva.virginia.gov/changemakers/

I have also been working recently on setting up a website to host the Library of Virginia’s many resources on women’s history. This is designed to be a mock-up of the future site, so my priority is creating a usable, attractive, and simple site upon which the Education and Outreach staff can continue to expand. We decided to use Omeka for this project as well, because the admin interface is very straightforward and will allow the staff to input all of their programs and data without having to know how to code. So, my tasks have included setting up the Omeka site on the Library’s server, downloading any plug-ins that they might want to use in the future, and creating a theme to style the website. I will be finishing up these responsibilities as I head into my last week of my internship.

0 notes

Photo

This week I focused several hours of my time on printing already completed finding aids and placing them into their corresponding boxes. This project took me longer than expected because of the similarity of content within the archival boxes and the lack of labeling on the exterior of the boxes. Once I sorted the boxes by content and people associated with the information, such as Thomas Chapman, Meg Kennedy, or Michael Quinn, I took several of them back to Montpelier’s storage facilities for permanent storage. I helped improve the process of finding the location of a particular box in the storage facilities by creating a more streamlined organizational system. When I began this summer, I might find a box of Michael Quinn’s papers with materials completely unrelated to him, and if I were searching for a specific box, it would take significant time to locate it. The process of cataloging the materials in each archival box has inevitably produced a more understandable storage system.

However, Montpelier’s Research Department suffers from a limited storage area, so many of the boxes that I have worked with will not fit into the facility. Pictured above are the boxes that cannot fit into storage that must remain in my supervisor’s office. I hope that Montpelier can expand their storage facilities, but I am sorry that I will not be here to help organize the overflow boxes into more permanent storage. If the Research Department is granted more storage, then the organization of archival materials will increase immensely and help make the archives more accessible to help answer the public’s research questions.

0 notes

Photo

More than a long walk on the beach.

Earlier this week and last week, I began the photographic part of my project. I started by doing a survey of churches around Esmont. I photographed and took notes about the buildings and their surroundings. Since it’s a rural area, several of them are a bit hidden. Some are tucked in the forest and up hills, well off main roads. Frankly, a few are well off even secondary roads

For people in Esmont -- again, a rural community -- walking was a major mode of transportation. Before cars were common, people recall walking through the woods to get to church. Having now seen the locations, I get a sense of how some of those walks to church would have been. It’s only a small exaggeration to say that it would have been a hike.

0 notes

Text

The Importance of the Liberal Arts at the University of Virginia, Pt. 2

Breaking Down Holcombe’s Main Points: the Goals of the University

1. “to furnish a constantly increasing body of young men, taken from the mass of society, with that degree of general culture which we denominate a liberal education” (block quote, post one)

Holcombe’s first point is the baseline for building the type of “learned class” which should be the goal of the university; namely, to provide all students with a liberal arts education (8). Holcombe believes the “acquisition of knowledge does not constitute the exclusive, or even the primary purpose of academic culture” (9). The best education is not one of rote memorization, but one in which the student “has most completely awakened his moral and aesthetic sensibilities, cultivated his taste, and developed and invigorated the whole circle of his intellectual faculties” (9). The college graduate will enter community life with a well-rounded education, and will serve as a community educator who will elevate the taste and sensibility of those around him (11).

2. “by superadding extended instruction in special departments, to serve the more important purposes of a Normal school, and thus to supply the State with a thoroughly educated and efficient corps of teachers”

Holcombe calls for the creation of an academic program exclusively for teaching, nonexistent at the university at the time of the address. He insists, “Teaching is a distinct profession, and like Law, Medicine, and Theology, must be pursued as an end in itself, and cultivated as an independent subject of study” (Holcombe 12). By placing it alongside Law, Medicine, and Theology, distinguished career paths, Holcombe elevates teaching, showing its importance to the school system and the creation of well-educated future citizens. Teachers at “common schools” (19c speak for “public school”) needed to learn from the great scholars at the university and then pass down this knowledge directly to the next generation. A body of well-trained men are responsible “to communicate to the masses as much as they can receive of the knowledge of the few” (12). Holcombe also points out how public schools and universities shared “reciprocal dependence”; well educated youths became more fully educated at university and then go on to educate more future students.

Lithograph of the University of Virginia in 1856, close to the date when Holcombe delivered his address. The original university library was housed in the Rotunda. (Photo courtesy of Wikiwand.)

3. “to provide such libraries, apparatus and collections as will afford to every class of students, the undergraduate, the professor, and the man of letters and science, all the means and facilities for original research”

Holcombe stresses the importance of the University library: “The possession of a noble library is a standing attraction to a University. Indeed such a library may be regarded as in itself a University.” (Holcombe 13) Without housing the proper texts, professors cannot be up-to-date in their fields. Researchers will not travel to the university. Students won’t receive the education they’re paying for. The University needs to appropriate more funds to the library, as it is lagging behind other institutions such as Harvard, Yale, Dartmouth, Brown, Bowdoin, and Georgetown, which are constantly acquiring collections and are still, according to Holcombe, inadequate (33). To illustrate his point, he mentions a study by Professor Jewett of the Smithsonian Institute, who shows most of the scholarly texts cited in current research cannot be found in the U.S. at all and certainly not at any one institution.

4. “The fourth and last function of the University is, by the complex, as it were, of these influences, to raise up a learned class, to keep alive the intellectual activity of the people, to quicken invention, to extend the boundaries of knowledge, to create and nourish a native literature”

By improving the university on these three points, Holcombe hopes it will be ready to move onto the final function of the university: “to create and nourish a native literature” (14). Only a “learned class...can furnish the authors to create and sustain a national literature. No nation can retain its character in the scale of history without a distinct and original literature…” (14-15).

0 notes

Text

In The End

Today was my last official day in the Monticello Archaeology Lab. It’s hard to believe it’s already over, there are so many things I would love to continue working on (the study collection drawer of buttons is fascinating, more below). This post combines the last two weeks of the internship, because last week was so busy I forgot to write up everything that had happened.

Last Tuesday, Wednesday, and Thursday, the archaeology department hosted approximately 32 teachers for the Teacher Archaeology Workshops (abbreviated teacher dig day from here on). These teachers dug in the field in the mornings and then moved on to the lab in the afternoons to complete a couple activities related to artifact processing and then a discussion of applications of archaeology in the classroom. For the most part, they seemed to enjoy the program, and I did too, but it was all-around exhausting. Teachers are good at asking questions.

I spent this week wrapping up a lot of things I’d been working on the past two months. For one, I continued organizing the study collection; I didn’t come close to finishing, but this is a project they’ve been working on for several years, and I made it through several more boxes of buttons of different types. Today I finished up military buttons, and was surprised by the number of navy buttons that have been recovered. I suppose this is because Monticello after Thomas Jefferson’s death was owned by Uriah Levy, a commodore in the US Navy (in fact, the first Jewish commodore of the US Navy).

I was actually successful in completing two other projects this week. For the past month or so, I went out and took pictures using the google street view app to create 360 degree images of different archaeological sites around Monticello, including several of the field school students at work. I came up with this idea to try and create an aid to our walking tour, because it’s been so rainy this summer that many of the tour groups weren’t able to make it to some of the sites. I’m also hoping that including a more digital aspect will encourage more young people to take the walking tour, since they’re notably not our biggest audience. The project will also be useful in that the pictures can also be shown at open houses and events, and during the winter, when we can’t take people down to the sites at all. The other project i completed was finishing a rough draft of an article about archaeology at Monticello and the field school for the Charlottesville Wine and Country Living Magazine. My draft is now being bounced around the department while everyone has the opportunity to read and edit it, and since the draft isn’t due to the magazine editor until August 10th--even though my internship will have technically ended--I’ll continue to work on this and remain a point of contact with the editor and photographer of the magazine.

While today is my last day in the lab, I will go in tomorrow to help run a family program at the Visitor Center. Children will be digging in our mock excavation units and then learning a bit more about archaeology. That will be my official last day in this internship, which makes this my final blog post, unless I think of something else I’ve forgotten! Bye!

0 notes

Photo

This week I have been finishing up the Guy Friddell collection. Friddell was a reporter who interviewed just about everyone you can think of. I found many tapes of President Jimmy Carter and his family, Muhammed Ali, Elizabeth Taylor, Mary Tyler Moore, and so many other officials and famous Americans. One name that popped up yet again was Jerry Baliles--that’s a running joke here because the former governor is in just about every business collection I’ve processed this year and we processed his own papers two years ago. Friddell also interviewed members of the Reynolds family--so I truly can never completely escape the ever growing Reynolds collections. Friddell also conducted hundreds of hours of interviews with Colgate Darden, yes the Darden of Darden business school and former UVA president. He actually wrote a book about Darden (we have several copies in the UVA library if you’re interested) so we have those transcripts and the original tapes here at the VMHC. Each of the tapes on Darden were labelled with some of the topics they covered, and they talked about everything from his childhood to the history of slavery especially it’s markers on institutions like UVA. There are also interviews from several other professors and about other professors at the University. It was a fun project to end my time at the VMHC with as I start to head back to UVA.

All of the audio-visual materials have been added to my database--at least all the ones we know we have from the collections catalogue and notes made about incoming collections. This week I also got to watch some of the old VHS tapes from the Damiani incoming collection so we could get a better idea of what that collection had. There were many blank tapes, but those that were used had film from Suffolk City Council proceedings and his news talk show. I also aided another one of the archivists in cataloguing photographs, postcards, and maps from various military bases around the Commonwealth. Some were from World War I--it was very cool to hold something 100 years old like that. Now I am working on processing Civil War letters, and it’s even cooler to deal with objects from the 1860s. Most of what I was working on this summer came from the 1950s-2000s. I only have five more days here, including today. It’s bittersweet, but it’s been fun.

0 notes

Photo

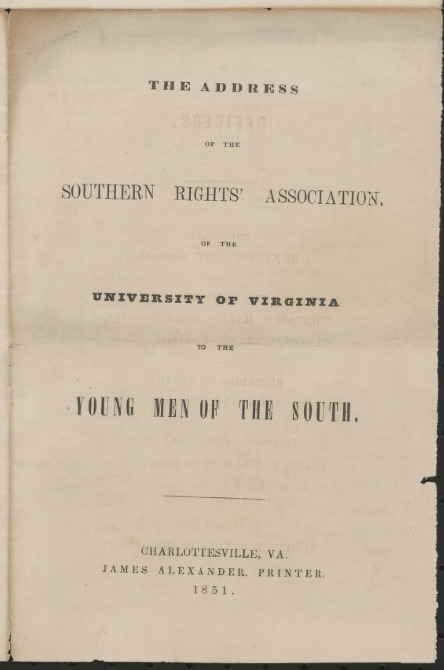

In early April 1861, Randolph Harrison McKim remembers waking to shouts and cheers across the Lawn and various student lodgings. He writes: “evidently something unusual has occurred. The explanation is soon found as one observes all eyes turned to the dome of the rotunda from whose summit the Secession flag is seen waving.” Despite the fact that Virginia had not yet seceded from the Union—the Commonwealth voted on against secession on April 4, 1861—“so general was the sympathy with the Southern cause that not a voice was raised in condemnation of the rebellious and burglarious act of the students who must have been guilty of raising the Southern flag” (McKim later confessed to being one such student). Though opposed by some, the support for the Confederate cause was overwhelming on grounds, even prior to Virginia’s swift secession from the Union on April 15th.

However, support for secession had been burgeoning at UVA long before April of 1861. Ten years before Virginia would secede, the Southern Rights Association at the University of Virginia was chartered, and by January 1851, the organization had produced a constitution, complete with an address (a manifesto of sorts), and a series of resolutions, signed by nearly a third (118/274) students enrolled at that time. The organization printed 2,500 copies of the Constitution, Address, and Resolutions to be distributed.

The address states: “But will the North stop here? We can not believe that she will. The war which is now being waged against the rights and honor of the South, will never terminate until slavery is finally banished from these shores. The insatiable spirit of Abolitionism which seems to possess our Northern allies, can never be appeased by any sacrifice short of this…Lodged in the hands of a large and daily growing Northern majority, it may at any moment be made the means of striking a deathblow to our interests, and our rights.” The address and resolutions would go on to inspire other universities’ Southern Rights movement, such as South Carolina College. The address itself was inspired by UVA alum Muscoe Garnett’s anonymously written “The Union, Past and Future: How It Works, and How to Save It,” identifying UVA as a site of the proliferation of confederate ideology.

Among slightly more laborious tasks (transcribing and marking up documents), I’ve been spending this week searching for records of pro-Secessionist or confederate sentiment at UVA during the 1850s, and trying to better understand UVA’s role as a hub of intellectual thinking about secession. Thus far, what I’ve found has been interesting and inconsistent—while the Southern Rights Association called for secession as early as 1850, writings and addresses given before the Alumni Society illustrate a wide variance among UVA-affiliated thinkers. While some called for immediate and absolute secession, some were staunch supporters of both the Union and the South, and some, of course, were Unionists themselves. While JUEL’s repository of 1850s documents is relatively small, I’m looking forward to delving more deeply into Special Collections to better understand UVA’s role in the creation of confederate and secessionist ideology. -Gwen Dilworth

0 notes

Text

Condition checking and label writing at the Gibbes Museum

A key part of collections work in any museum or cultural institution is condition checking, meaning to go over in painstaking detail every inch of a work of art and record any change that has occurred since the last report. I performed this task for an incoming loan of Hudson River School paintings, which had very ornate frames that needed to be carefully examined. I noted when items had been damaged while they were away, not necessarily due to any wrongdoing but simply because they are mid-19th century gilded, fragile structures. After noting the damaged pieces our preparator, Chris, performed remedies. I condition reported all of our 18th century furniture on loan in our main gallery as well.

In this picture I am condition reporting the Porcher Linen Press made in 1785, noting any new cracks, nicks, or discoloration on the surface of the object.

A few weeks ago I posted that I had selected The Fruit Man by Thomas Wightman to be displayed outside our storage area as our highlighted object. This week I picked a new object. I selected a 1980 Jack Leigh photograph of Annie Mae Gadsen and Henrietta Kitty, shucking oysters. I was drawn to Leigh’s photographs in our collection because he was very adept at capturing the beauty of rural oystering lifestyles. His photographs range from quiet, unpopulated river scenes to dynamic photographs of workers amidst the steam, spray, and shells of the processing factories. I decided on this photograph because it was the only one in our collection where his subjects were named, and I felt that it was important to acknowledge the identity of these hardworking, charismatic women. In 1980, Jack Leigh felt an urgency to capture this lifestyle, feeling that younger generations were leaving the islands in greater numbers and reducing the labor population on the island. I was able to get in touch with a local oystering expert and asked her if she thought this lifestyle had indeed changed drastically. From this brief correspondence I learned that at least in Beaufort county, the oystering industry is still predominantly family-owned, with some families having harvested oysters for four generations (since the 1890’s). Perhaps this way of life has not vanished as Leigh predicted, but rather the industry is threatened more so by overharvesting and high levels of pollution. That being said, it can grant a moment of serenity to look to Jack Leigh’s photographs and reflect on the earnest people he portrayed. All of this information and more I included in a label and it is not on display outside storage.

I have relished opportunities like these to incorporate my Anthropology background and not only reflect on what art means visually, but reflect on the people and cultures both behind and in front of the lens, paintbrush, pencil etc.

0 notes

Text

Miller’s Mark on Albemarle

A photo of the Miller School in Albemarle, courtesy of the Boarding School Review.

If you’ve lived in Charlottesville for a couple years, you’ve probably wondered: why are there so many things named after “Miller”? There’s the Miller School, located in the Samuel Miller Loop, and Southwestern Albemarle County even has a Samuel Miller Magisterial District. Although the facts about Samuel Miller’s life are somewhat scattered and uncertain, here’s what I found out:

Samuel Miller was born in Albemarle County in 1792. Raised by his mother, he lived a humble life in the mountains with his older brother, John. They studied in the county’s common school (essentially our public school), where Samuel worked just as hard as he did at the farm at home. After his schooling was complete, John moved to Lynchburg and opened up a grocery (Daily Progress). Samuel began teaching, showing an early commitment to investing in others’ education just as fiercely as he invested in his own (Crozet Gazette). Once John was financially stable enough, Samuel joined him in Lynchburg, where they became successful businessmen (Whitehead). In 1814, the two purchased a farm outside of Batesville, where they moved their mother. Ever mindful, the Miller sons asked local merchant Nicholas Page to make sure her daily needs would be provided for and to inform the brothers of anything else their mother might require (Crozet Gazette).

In 1841, both Samuel’s mother and brother passed away. Samuel continued to live in Lynchburg, inheriting and investing his brother’s assets. By trading goods such as tobacco, Miller amassed a huge profit, gradually building his estate until it totaled $2,250,000 (Daily Progress). According to online inflation calculators, if Miller’s estate was this large near the end of his life in the 1860s, it would be worth approximately $40 million in today’s currency. Lynchburg biographer R. Colston Blackford speculated Miller was one of the “ten richest men in the United States” (Crozet Times).

As one of the richest men in Virginia and the South at large, what did Miller do with all his money? Although “reclusive and frugal in his personal life” Miller was known in his resident town of Lynchburg for his generosity and community investment (Historical Marker). Miller’s main focus was funding educational programs. In 1859, Miller’s will endowed the Miller Manual-Labor School of Albemarle, now known as the Miller School of Albemarle. Miller passed away in 1869, and Page took over as executor of his estate, beginning the arduous process that would finally produce the school Miller intended. The Virginia Legislature passed the act to approve the Miller School as of February 24, 1874 (Whitehead). The first students, a class of 20, enrolled in 1878 (Whitehead). By the 1891-1892 term, 173 boys and 93 girls were in attendance (Whitehead). While The Miller School was one of his most visible endowments, Miller also provided funds to establish the Lynchburg Female Orphan Asylum. Another one of his large donations was to our very own University of Virginia. Looking through the University of Virginia’s Board of Visitors Minutes from September 16th, 1869, I came across discussion about the Miller Trust, which Samuel provided to the university to establish a new School of Experimental and Practical Agriculture (BOV Minutes). This appears to be just one of his many contributions to the university community.

Regardless of his philanthropic efforts, it appears Miller was not widely known outside of his small Virginia circle. A Daily Progress article circa 1900 details the life of Miller through the eyes of Nicholas Page, friend and executor of his estate: “Probably you would have never heard of [Samuel Miller]…but there are hundreds of men, yes thousands, who have received manual training at the school Samuel Miller established” (Daily Progress). Although it has undergone many changes overtime, the Miller School is still in use today as a boarding and day school.

Works Cited:

“Board of Visitors Minutes: September 16, 1869.” Board of Visitors Minutes, University of Virginia Library, xtf.lib.virginia.edu/xtf/view?docId=2006_06/uvaGenText/tei/ bov_18690916.xml&chunk. id=d3&toc.id=&brand=default.

“HISTORY.” Miller School of Albemarle, millerschoolofalbemarle.org/history/.

“Michael Marshall.” The Crozet Gazette, 4 June 2015, www.crozetgazette.com/2015/06/04/secrets-of-the-blue-ridge-batesville-on-the-old- plank-road/.

“Samuel Miller - Lynchburg - VA - US.” Historical Marker Project, Historical Marker Project, 2014, www.historicalmarkerproject.com/markers/HM1YYQ_samuel-miller_Lynchburg- VA.html.

Strider, Robert. “Samuel Miller House.” Clio, 19 Mar. 2017, www.theclio.com/web/entry?id=34510.

Whitehead, T. Virginia: a Handbook: Giving Its History, Climate, and Mineral Wealth, Its Educational, Agricultural and Industrial Advantages. Waddey, 1893.

Photo credit:

“Miller School of Albemarle .” Boarding School Review, Boarding School Review LLC, Charlottesville, 2013, xtf.lib.virginia.edu/xtf/view?docId=2006_06/uvaGenText/tei/bov_18690916.xml&chunk. id=d3&toc.id=&brand=default.

0 notes

Text

I started this writing as a mere tumblr post, but then realized that it may become a useful written product for my internship...

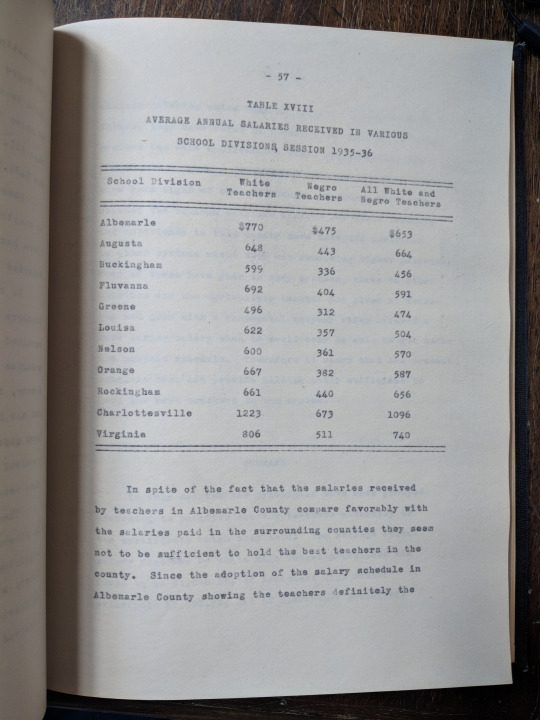

Educational opportunities for blacks in Albemarle County were generally poor before desegregation. Well into the first half of the 20th century, it remained common for some black students to stop their education after primary school. In addition, public black high schools tended to push vocational education. This was due to segregationist policies that kept blacks out of positions of economic power.

Since the government treated black schools as an afterthought, community involvement played a significant role in creating and supporting Esmont’s schools. Local leaders formed an “Educational Board” in 1907, and residents raised money to fund new schools. Outside philanthropic entities, like the Jeanes Fund (officially the “Negro Rural School Fund”), also helped.

Still, the students’ needs were inadequately met. Older Esmont residents recall walking several miles to school, as school bus service for blacks was either extremely limited or nonexistent. One woman I spoke with attended the county’s circa 1950 consolidated black high school, named Jackson P. Burley High School. She recalls being unable to participate in after school activities because Burley was in Charlottesville, miles from Esmont. If she stayed late at Burley and missed the busses’ departure, she would not have transportation home. She especially lamented how rural kids could not get help with the college process from school counselors. Those meetings occurred after school hours, and were more easily accessible for city kids who could walk home afterwards than for rural kids whose homes dotted Albemarle County’s vast expanse.

Students who went to college under segregation almost invariably attended black institutions like Virginia State College, Hampton Institute, and St Paul’s (the first two now universities and the last one defunct). There, many learned to teach or learned trades. Afterwards, they returned to their home communities to raise the next generation, who would more or less follow in the same cycle until desegregation. This formed a self-contained black society that ran parallel — underprivileged and unequal — to white society.

Some of those who broke from the routine went north, which offered more socioeconomic opportunities. One man, Roger Yancey, born the son of a prominent Esmont educator in 1902, graduated from Hampton Institute and went on study law at Rutgers University. He eventually became a judge in New Jersey, a position he could not have held in segregated Albemarle County.

https://www.ncpedia.org/jeanes-fund

http://www2.vcdh.virginia.edu/afam/raceandplace/oralhistory_esmont1.html

http://www.aahistoricsitesva.org/items/show/220

From “The Teacher's Salary in Albemarle County, Virginia, and How It Is Used” by Joel Thomas Kidd, 1937

1 note

·

View note

Photo

The past week has been really illuminating - I only wish that I would have been able to make it to the Eastern Shore earlier. Today, I visited the Cape Charles Museum and Welcome Center, where there is currently an exhibit on the Cape Charles Elementary School. Also known as a ‘Rosenwald’ school, it served black students before and after the desegregation of schools in 1954. I had the great fortune to read through some of the oral histories of teachers, students and the relatives of those teachers and students associated with the school. These oral histories were conducted in 2013 and 2014, and were directed by Linda Schulz. The transcripts describe the day-to-day operation and goings on of the school itself, as well as what was going on regionally and nationally during the 1930s-1960s. These priceless interviews provide truth to the realities of life growing up black in the South in the first half of the 20th century. The remainder of the welcome center contains some of the infrastructural elements of the city of Cape Charles, including an (enormous) electric generator and models of the Chesapeake Bay bridge tunnel. Cape Charles is the Southernmost city in the Eastern Shore of Virginia, providing an outlet/inlet point between the Delmarva Peninsula and mainland Virginia. I particularly enjoyed the large scale model. Very 60s! I will be adding various items from these collections to the ArchivesSpace repository for the Eastern Shore Museum Network, and look forward to reporting back from the other dozen or so member institutions in the coming days. Cheers Kyle

0 notes

Photo

During the past few weeks, several changes occurred in my internship at Montpelier. During the week of July 2-6, the leadership of my internship has altered slightly due to my supervisor transferring my project to a coworker. This transition has been smooth, and since the majority of my work is independent, little has changed regarding my objective and work for my internship. Under my new supervisor, who I am already familiar with due to a shared office space, I will continue to catalog archival documents from Montpelier’s archives, and she will be the individual who takes me to Montpelier’s archival storage facilities.

After a brief vacation, I returned to Montpelier the week of July 16. This week the archival records focused primarily on media content and press records of Montpelier news, especially concerning the mansion’s renovation process. I read and recorded hundreds of newspaper and magazine articles publicizing Montpelier. Although the majority of the articles originated from the Orange County Review and local publications, I found several articles from The New York Times and The Washington Post, emphasizing Montpelier’s national exposure. One article that surprised me was “Vandals Hit Historic Montpelier Tombstone” explaining how individuals trespassed and toppled the monument on Dolley Madison’s grave (pictured above). It does not explain the vandals’ motives, but I remember feeling a pang of dismay when I learned the monument could not be restored to its original condition, as you can see by the wide crack through the stone. This reaction reminded me why I became interested in public history; I want to help preserve historical sites and documents and extend my appreciation for the past by sharing it with others, which will hopefully in turn increase protection for historical objects.

0 notes

Photo

Lincoln here, checking in from the Gaines’ Mill Unit of the Richmond National Battlefield Park. One of the perks of working for the National Parks Service is the amount of time that I am afforded outdoors, and I have been fortunate enough to get intimately acquainted with many of the Civil War sites preserved in and around Richmond. One thing that always strikes me about many of these sites, including the Gaines’ Mill battlefield site pictured above, is the almost idyllic beauty of many of the modern day park sites. This contemporary tranquility stands in stark contrast to the death and suffering witnessed by so many of the sites, however, and such dissonance can at times be striking. Had I been standing at the spot where this photograph was taken in 1862, I would have witnessed one of the bloodiest single days of the Civil War; had I been standing in the same site in the decades prior to the War, when this farmstead was operated by the slave-holding Watt family, I would have witnessed the immense suffering endured by those held in bondage on the very same ground. That a site which is today so calm has, throughout its history, been host to such suffering, is a testament to how far our nation has come in the 156 years that have passed since the War, yet the sordid history of the battlefield and farm speak to how far our nation has yet to go.

0 notes

Text

The Importance of the Liberal Arts at the University of Virginia

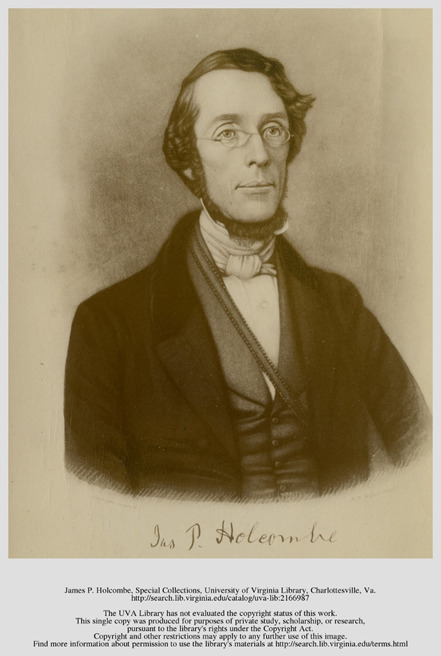

Introduction: The Address of James Holcombe (1853)

On June 29, 1853, lawyer and future Confederate politician James P. Holcombe delivered an address to the Alumni Society of the University of Virginia. According to tradition, and upon the society’s request, Holcombe focused on the subject of a liberal arts education and its importance to the university in general and UVa in particular. Viewing UVa as lagging behind other comparable institutions, Holcombe urges the university to produce good teachers, which will in turn create a more prepared future student body; reassess its curriculum and strengthen its liberal arts program, specifically to develop a literature department; and expand and bolster their library. All these pieces he views as essential steps in the pursuit of a ‘native’ literature, as politically important for the south as it is for the nation as a whole in globally redefining itself.

Image courtesy of UVa’s Special Collections.

Holcombe begins his address by going back to the basics. He discusses the function of the university in general, comparing the American university system to its English predecessors. Above all, he reminds the listeners that the functions of a university are “literary as well as educational” (7). Holcombe outlines what he views as the four major “functions” of the institution of the university:

first, to furnish a constantly increasing body of young men, taken from the mass of society, with that degree of general culture which we denominate a liberal education; second, by superadding extended instruction in special departments, to serve the more important purposes of a Normal school, and thus to supply the State with a thoroughly educated and efficient corps of teachers; third, to provide such libraries, apparatus and collections as will afford to every class of students, the undergraduate, the professor, and the man of letters and science, all the means and facilities for original research: fourth, by the combined operation of these influences, to raise up a learned class, to stimulate the progress of inventive art and scientific discovery, to quicken into life and feed with perpetual aliment to the creative spirit of a national literature. (7-8)

Of these subjects, Holcombe says, “So intimate is their connection, so constant their action and reaction, that a University which is not in itself, or by means of kindred and supplementary institutions, equal to the discharge of all of these functions, will be found incompetent to the perfect performance of any of them” (8). He goes on to illuminate these main points throughout the rest of his address.

More to come in the series: (Re)defining Liberal Arts at the University of Virginia: From Its Establishment to the Present, The History of Liberal Arts Education in the United States, and The South’s Stake in National Literature

Work(s) Cited:

Holcombe, James P. “An Address Delivered Before the Society of Alumni of the University of Virginia.” An Address Delivered Before the Society of Alumni of the University of Virginia at its Annual Meeting Held in the Public Hall, June 29, 1853, Charlottesville, Va.

0 notes

Photo

This week we are going through the unprocessed collections to look for audio-visual materials. These are the collections that we have received, but that have not been catalogued yet. In these records, we found audio-visual materials from Circuit City, The Science Museum of Virginia’s Reynolds Collection (you can never escape them), and Guy Friddell.

In the Reynolds materials given to us by the Science Museum I found the film shown above. This took us on a research tangent because usually red dust like that on film can only come from the break down of nitrate film. For those of you who are unfamiliar (as I was at the beginning of this project) with nitrate film, it has been essentially banned since 1951 because it randomly bursts into flame. The tricky part of identifying this film was that it also had the strongest vinegar smell, and Vinegar Syndrome can only be found in acetate based films (which nitrate is not). We found two other tins with similar problems to these two rolls, and one of them said safety (aka not nitrate), so we are going with the vinegar smell and calling this triacetate film. Hopefully the rust dust was from some kind of reaction between the metal canister and the vinegar breakdown of the film. If it wasn’t at least the films have been rehoused and there are no windows where they are stored...

Now being officially officially officially done with Reynolds--we have searched every section of the archives and there should NOT be anything else (knock on wood)--I’m going through the Guy Friddell collection. Friddell was a reporter and he interviewed basically anyone who was anyone in Virginia. He also uses the most diverse media selections out of all the other collections. Above are his mini cassettes, and he also used 1/4″ magnetic audio tape, regular sized cassettes, VHS and Umatic tapes. Many of his audio tape interviews have also been transferred onto CDs. This is the last of the unprocessed collections I have to go through and with only 10 days left here everything is sort of coming to a close.

At least in my last few days I will keep running into amazing things like these interviews with some pretty famous UVA related people. It’s weird to think about Newcomb hosting such an official conference when I’m usually just eating Chick-fil-A there in the PAV, but that was a cool find. The interview with Faulkner has been transferred over to CD, so I am hoping to listen to it before I leave. I know UVA put our Faulkner lectures up online, and it would be interesting to see if this one is already in that collection or a new piece that UVA doesn’t have.

0 notes

Text

Monticello Archaeology Week 7

This past week involved a lot of “lasts.” It was the final week of our field school, so the students wrapped up a lot of the excavations they’d been working on. The site summaries on the last day of excavations were rather surprising to me; for the past year, ever since I did field school, we’ve always discussed the two potential houses at this site. However, due to this seasons excavations and the artifact density maps that were created with the most recent data, we’re actually starting to think there is a potential third house beyond where we have dug in the past. That was a pretty wild discovery, although it might not have been new information for everyone else. I’m not entirely sure if this was a hypothesis that had previously circulated around the department and I had just missed it, or if this was wholly new information. Anyway, after the site summaries, the only thing left for the field school was reviewing for the final exam and then taking it, so I’ve been working more on the article about the field school and ongoing excavations at Monticello for the Charlottesville Wine and Country Living Magazine. I am eagerly waiting to see the pictures taken by the photographer who came last week.

We also had our last visit from the Monticello Children’s Summer Camp. This last bunch of campers can best be described as boisterous, but they also seemed to be very interested in archaeology. I went to the Summer Camp wrap-up on Friday, and the campers all talked excitedly about their visit to the field and the lab. In fact, two parents came up to me afterward and asked if there were other archaeological programs in the area they could do, so I guess we made a good impression.

This week, I’ll be in the field digging from Tuesday onward because of the Archaeology Teacher Workshops, and I am very much looking forward to excavating again. More on that later!

0 notes

Text

I only spent 1 (!) day this week in Special Collections. This time, I read through a commemorative history made by one of the Esmont area’s churches, Chestnut Grove Baptist Church. I also read some minutes from the Rockfish and Piedmont Baptist Associations, which some Esmont churches are members of. Interestingly, the Piedmont Baptist Association was primarily white for most of its history, but sometime in the 1950s and 1960s a change occurred. The minutes from 1964 list predominantly black churches as members of the association; minutes from the 1950s list white churches. Another possibility is that there were parallel associations for white and black churches, but the minutes give no explanation.

I also found a school newspaper from Esmont High School (black), which provided some first-hand accounts of young African Americans’ experience of segregated America in 1944. The paper includes the written speech of one student, Angelena Burton, who criticizes the federal government for proclaiming to stand against “medieval methods” practiced by Hitler, while simultaneously continuing discriminatory policies in the United States.

0 notes