Text

Remembering Ms. Velma Perry: A Tribute

The Jackson Center's motto is without the past, you have no future. Ms. Velma embodied this more than almost anybody I've ever met. In fact, I'll never forget my first town council meeting with Ms. Velma (which I should note was probably her 1,000th meeting). Ms. Velma got to the microphone and started, "Now you all need to know some history. Back during the war…with the English, in the 1700's...my great great grandmother…" Now, as many of you know, at Chapel Hill town council meetings, there is a 3 minute time limit for comments. By the time three minutes, five minutes, had passed, Ms. Velma was still in the 1840's. And the mayor -Mark Kleinschmidt at the time – did not know what to do. He couldn’t ask this 90-year-old seasoned activist to sit down or hit the buzzer like they do for most people. So she went on: 8 minutes, 10 minutes, 15 minutes. Now most people when they go on this long don’t have a point. Ms. Velma did. She wanted people to know that black people had been in this neighborhood for centuries and that they had a right to stay here. She wanted every council member to know that when they voted on a development moratorium and changes to protect the neighborhood, they weren't just voting on a current issue. She wanted those investors sitting in the audience to know they couldn't get away with this. This issue had history, and that history was deep and challenging. And Ms. Velma's people had built this town and university; they made everything here possible. She finished by claiming something like: "And now, you have a chance - will you support the black people who have been here for centuries, or will you let us be pushed out of the town we have built?

Ms. Velma lived in her same home on Lindsay St for 98 years. Living 98 years is remarkable; living 98 years in the same home is unheard of. Except with Ms. Velma. Can you imagine how well she knew this place? She saw this neighborhood change drastically, but she didn't sit by and watch change. She helped define it, fight for it, make it better. She fought for noise ordinances, trash rules, conservation districts – anything and everything that would help preserve its dignity. She fought well into her 90's and inspired many of us younger people to see that our voices could make a difference. And she was an exemplary neighbor, always greeting people from that expansive porch. Sometimes I’d see her visiting with a young person on the porch and stop to ask who it was; often, she wouldn’t even know. She was just telling her story to a new neighbor. Ms. Keith Edwards once said that there is a difference between a house and a home: a house is bricks, wood, a structure. A house becomes a home when the people in that house represent a sense of community, a sense of belonging, a sense of kinship. Ms. Velma helped define home for so many of us. We so need neighbors like Ms. Velma who ground us in what real community looks like, who share the history of a place, and who defy "market forces" to stay in that place for—and for the benefit of--generations.

As most of you probably know, Ms. Velma had a beautiful voice. She could sing. And whenever we got the chance—holidays, birthdays, Valentine’s day-- a group of us from the Jackson Center would go to serenade her. In recent years, Ms. Velma could not remember the words to songs anymore, but she would grab our hands and, in that stunning operatic tone, she would sing. Ms. Janie of course—her constant caregiver and companion—sang along and cheered her on. I witnessed dozens of folks moved to tears by the beauty of Ms. Velma - at 96, 97, 98 years old - sitting up all of a sudden to join us in song.

The words no longer mattered when Ms. Velma sang; she had the spirit. She made the songs so much more beautiful And I think in life, as people of faith, this is what we can most hope for - that even if a lot of ourselves leave us, our memories leave us, that deep spirit of faith, the blessing of communion with neighbors, our ability to break into hymns of praise we have sung our whole lives through - that if that is what remains, we will know we lived, truly lived a beautiful life just as Ms. Velma did.

-- Hudson Vaughan

1 note

·

View note

Text

Works Without Faith

I attended a funeral last week, which was a strange experience for me, because it is the first one I have ever attended. I did not know the person who passed as well as I would have liked to, but she was a massive figure in Northside and the surrounding communities. Her name was Mama Kat. Mama Kat was a woman who regularly volunteered with St. Joseph CME’s Food Ministry (AKA Heavenly Groceries), where food is collected and given to people who otherwise may not be able to afford it. That’s really an understatement though; she was omnipresent. Of the many volunteers that came through the Ministry, most of them recalled getting to know her as one of the most impactful parts of the whole experience. I count myself among them.

The day before the Funeral, the Jackson Center held a meeting, and everyone was asked whether or not we were willing to go to the funeral to show support for the family. I was the only one who hesitated despite half the table being populated with the Center’s other Summer Fellows, many of whom had been working at the Center for a much shorter time than I had, had known Mama Kat for a much shorter time than I had. But I hesitated, and I said, “My concerns are that I have a meeting at three, and I’m not sure I have the right clothes.” I did have a meeting, but I knew that we would be back before then. I knew I had the right clothes, but that was all that came out of my mouth when my real hesitation was that I was terrified at the idea because I did not know how to act at a funeral.

I have trouble coping with the thought of my own mortality, let alone how to properly respect someone who had just crossed beyond the veil. Besides, I didn’t see myself as very religious. I didn’t go to church very much at all growing up, and my interactions with religion had only ever been linked with those who wielded dogma to justify their bigotry, or else quietly went through the motions of faith without truly believing. I didn’t know what to expect, and I didn’t want to embarrass myself.

Della, our former Executive Director looked at me and said, “we will be back by then, and there is no right outfit.”

So the next morning I got up early and donned a white dress shirt and suit jacket I had recently brought back from my hometown on a whim, along with black dress shoes I didn’t know I even owned. I gently fastened a thin black tie around my neck that I had borrowed from a friend a long time ago and never given back since we mutually forgot about it. My entire outfit was an accident, some sort of serendipity that I started off that morning struggling to rectify. Had things been slightly different I wouldn’t have had that outfit.

We got into the car and drove out to the chapel in the country. Looking out at the woods as we passed by, they reminded me of the mountains and the pine forests which have surrounded the homes I have known in my life. We made small talk on the way and remembered Mama Kat’s life. I wished I had more to say, and I wished I had known her better. I wished I had put in the work to know her more before she passed.

We talked about how fortunate it was that The Jackson Center had preserved so many Oral Histories of Mama Kat, so that even though she had passed, her words would not be lost. Even though she was gone, her spirit could not be extinguished and would continue to live on in the hearts of those who remembered her voice and the ears of those future children who might know her through the stories we had saved.

When we arrived at the funeral, I was still anxious. Most of the people there had known Mama Kat for much of her life, were related to her, or worked with her. I was a just a white guy in a suit that no one knew, who had hardly ever been to church in his life, who didn’t believe in God, or in the Heaven that Mama Kat’s family knew she was cutting up in right as they spoke.

We walked in and through the beautiful church, and it was mostly already full. Soon enough we were ushered downstairs to the Fellowship Hall to watch the funeral on a television feed. Part of me had wanted to just stand against the wall for the whole ceremony rather than watch it on the television, but I knew there were more people coming in and there would almost certainly be people closer to Mama Kat than me who would have to watch on the television screen as well, so I just resolved to be present and listen.

To my surprise, all through the ceremony I couldn’t help but feel connected to it emotionally in ways I couldn’t really articulate. When I saw people walk over to the casket during the visitation and clutch the side of the box while staring down at their loved one, I felt that anguish and memory. When the church broke into song between speakers I wondered why I had to all but stop myself from singing along. Perhaps I should have sung along, but I didn’t know the words, and the basement overflow was not full of the singing and clapping that took place overhead.

But these feelings moving through me, this inarticulate connection, was only a dull hum compared to how I felt watching the pastor come to the altar and preach. He spoke of Mama Kat, of her work, of her character, and most importantly of the power of faith. Even all the caricatures of poor sermons in the world, full of hollow repeated verses and over worn Bible passages, could not have prepared me for the sheer power of someone using the text as a means for conveying their belief rather than someone speaking the same words as meaningless ritual. It was as if he were giving a speech through poetry as common prose, no matter how carefully chosen, would be unable to do the job. It felt as if something would be lost in those phrases like the energy between the words, the power of the lyric, or the context of the passage.

And so I wondered, a young man in an unfamiliar chapel who had never so much as stepped in a church since the age of six, why I felt myself on the verge of tears when the pastor proffered that “faith without works is dead.” Why was I shaken by the hymns? Why did my hands tremble at the sight of someone I had hardly known passing beyond this world?

I’m sure that many religious people might say that the power of the divine was affecting me, and I do not necessarily disagree. Many might say that I felt the awe of God.

But, despite my feelings, I grew up never believing in God, and I still cannot square my experiences with the existence of a God. So I’m left wondering what I do believe in.

Later that week I listened to another oral history we have in the archive at the Jackson Center. In it, the narrator speaks often about how he lets God use him, how he is often compelled to see and do things by something he feels is outside of himself; the power of God.

Strangely, the feeling is very familiar. The way he talked about being used by God sounded to me like the time I went to a protest and felt compelled to join the other activists in blocking an intersection. So filled with purpose was I at the time that looking back, the thought had not even crossed my mind that the action could have resulted in my being hit by a car or arrested. The way he talked about being used by God reminded me of how I felt when I had my first kiss, inconsiderate of anything other than the moment. The way he talked about being used by God reminded me of all the times I have reached out to someone I knew would have no time for me, but made time anyway. The way he talked about being used by God reminded me of how I have felt every time I have been brave in my life; every moment I made a decision I knew was right in my heart, in my bones, without being able to explain why.

How do I explain those moments to myself?

The short answer is that right now, I’m not sure.

What I do know is that those moments are necessary, that faith is necessary. Faith is in the bold, faith is in the world changing. True faith is inseparable from creating tangible change, because both rely on a suspension of material understanding in order to believe in a reality that is greater than the one currently experienced. How could protesting Candy-Coated Racism and sitting down in segregated stores, knowing you might get beaten by police or pummeled with a fire hose in order to secure a more just future that you can scarcely imagine, be that much different than having the courage to continue living devoutly through strife in order to live on eternally in a Heaven one can scarcely imagine?

Faith and Revolution have been long separated in the Western ideological canon, from the Cult of Reason to elitist critiques of the Civil Rights Movement, but I am beginning to think that this is a foolish error.

When that pastor said that Faith Without Works is Dead, he meant that it was not enough to believe in something without acting to better the lives of your brothers and sisters. Faith unmoored from a genuine mission to enrich the lives of others is hollow and vain. I would like to posit that the reverse is true. Works without faith are precarious.

The challenges facing this generation are colossal, are bigger than ourselves, and are so big that it is hard to feel like we are making any difference in changing them. People simply cannot understand the numbers of the big picture, you can’t visualize 3,000 tons of garbage. What we can visualize is our story, and what we want the world to look like in thirty years. Those who care most about creating a better world for our children, given a material understanding of our circumstances, are some of the most highly affected by anxiety, depression, and attention disorders. We are burnt out. We are tired. We are constantly second-guessing ourselves.

So often, our intense work is matched by an unrelenting nihilism that despite our efforts, things will never be better materially, and there is certainly no such thing as a life beyond this life where they will be better. But we need to believe that change is possible, that a better world is possible, because that faith is what keeps the lamp alight when all the other fuel has run out. For me, I think this means that my generation and activists writ large need to need to rediscover faith, a faith that feels authentic and true in our bones if not our heads. We need to decolonize ourselves and recognize that sometimes things can be true without being provable, at least on a personal level, even if that truth is not the existence of a God. And most importantly we need to feel genuinely that faith is radical, and radicals must have faith.

Faith without Works is Dead

Works without Faith don’t Last

— Wyatt Woodson

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Who are my neighbors? -- A Student’s Role in Gentrification

by Kayla DeHoniesto, 2019 Jackson Center Summer Fellow

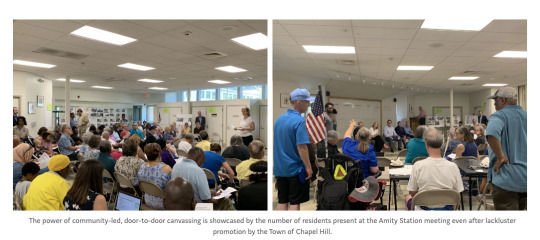

As I walked out of the Amity Station Community Meeting, on my second day of this fellowship, I could not process the thoughts and emotions running through my head. I could sense anger, frustration, guilt, heartache, and excitement all in one. Each emotion fought for prominence in my brain, but I ultimately walked away from that meeting confused; confused on what there was left to do and what my personal role was in this new community I had adopted. But in order for me to understand my role in fighting the gentrification affecting Northside, I had to first understand what the neighborhood means to me and to its residents.

I have lived in predominantly white neighborhoods and operated in predominantly white spaces my entire life. The last true Black community I belonged to was Girl Scouts and my church, but both of those communities were cut from my life when I moved states. I bring this up not to give reason to why I don’t feel connected to Black spaces because every day I bask in the glory of my Blackness. However, I think the lack of a community of people who not only look like me but can provide comfort when navigating the realities of being Black in America have left me longing for a particular type of connection. I have never felt connected to elders who lived through the struggles for freedom that afforded me with the privileges I have today. But Northside is different from any community I have ever known because the connection between residents is infectious and special, vibrant and established. When you meet the people of Northside, you meet people who immediately feel like family, and a neighborhood that is so connected it almost feels like the textbook definition of what community should mean.

This legacy of community does not exist in a vacuum, and it is not purely a side effect of Blackness. Northside remains united because of the common experience of struggle, the historic spirit of fighting for civil rights, and the power of collective memory that keeps people together. And it is the spirit of that connection that makes its slow disintegration that much more tragic. The growth of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the city around it has created a major development boom in the town, especially in regards to student housing. Northside, which has been historically Black and low-income, has become a hub for developers and investors to create new student rentals, thus changing the demographics of the neighborhood while also hiking up the property taxes for long-term residents. Thus, the lifetime residents of Northside who created its thriving culture have been systematically pushed out not just by the rising costs of living but by the loss of a sense of community in their neighborhood. I have talked to residents who have seen almost every house on their street transformed into expensive student housing, thus pushing out families who want to live in Northside and erasing the close-knit community that made Northside a safe haven for Black families for decades.

This is gentrification at its finest.

The Oxford dictionary defines gentrification as “the process of renovating and improving a house or district so that it conforms to middle-class taste.” There is nothing inherently wrong with a natural change that takes place over time, especially within a community Northside, which has been around for decades, since well before the Civil Rights Movement. But when the so-called “improvement” in the neighborhood only benefits profit-driven developers and oblivious students who aren’t aware of any communities outside of campus, the residents who make up the backbone of Northside become an afterthought. The histories, legacies, and culture of what was a vibrant beacon of Black life in Chapel Hill have been decimated by the expansion of a university that boasts development and innovation while simultaneously erasing the legacy of the families that built it.

As a student, I feel torn. On one hand, Northside provides so many of my friends more affordable housing than on-campus dorms and fancy apartment complexes, so I understand the desire to live there. But as an activist and a fellow of the Jackson Center, I am witnessing firsthand the devastation that student rentals cause for this community. I struggle to find a middle ground between supporting long-term residents of Northside who have provided me with so much wisdom and compassion, while also knowing that many of my friends would struggle to pay rent in other neighborhoods. At what point do I stop being a student and begin advocating for this community? Are they separate roles? Can I ever truly fight the gentrification of Northside while continuing to go to parties and visiting friends in Northside?

I think one of the hardest parts of activism, or just being a citizen who is aware of the injustices around me, is not knowing how much impact I can really ever have. I wonder about how much power I have against the powerful tides of gentrification, and how does my role as a student play into understanding and connecting to the community around my institution. I also struggle to decide how much students are at fault for giving in to the greedy operations of developers who seek profit above humanity. Is it more effective to place the blame on developers, students, or both? Sometimes the impact and change I would like to make in the world around me seems too big for a tiny person like me to manage.

For me, I think this work starts with just learning who my neighbors are and what Northside means to them. I think we can look to Northside, where justice and activism flow through the blood of almost every long-term resident, as an example of what community-based activism can accomplish when everyone is invested in the fight against gentrification.

-Kayla DeHoniesto

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Remembering the Election of Howard Lee and the Power of Community Organizing

Many locals will proudly tell newcomers that Chapel Hill, North Carolina, was the first majority-white town in the South to elect a Black mayor. The year was 1969. Though many told him it was too soon after desegregation and the town wasn’t ready, Howard Lee launched a campaign anyway. He used a strategy much like the one Barack Obama used to win the Presidency a few decades later: grassroots community organizing of the most thorough sort.

Lee and his wife had moved to Chapel Hill in 1964; he got a master’s degree at UNC, and then began teaching at Duke and North Carolina Central. Their story tells a lot about the climate at the time. As he told WUNC interviewer Frank Stasio decades later: “I had tried to buy a house in Chapel Hill and no realtor would sell me a house. We finally ended up buying a house by working with a white family, by tricking the realtor.”

I have heard a lot of stories like this one, about black people with audacity and their white accomplices, who chipped away at segregation. There are the stories of the legendary Dean Smith who entered segregated eating establishments with his black players and requested a table. And a couple I know who did the same with their black friends. And the students who demonstrated, sat in front of segregated stores, and engaged in various acts of civil disobedience.

And yet the fact remains: in the mid-1960s, after businesses had officially desegregated, black university professors were denied housing outside of neighborhoods historically designated as “black.” The Lees and their two children received death threats, and the Klan burned a cross on their front lawn. As Lee puts it: “There were some nasty, nasty events in Chapel Hill during the civil rights era.” He twice went to the Town Council asking them to pass an open housing ordinance. City officials refused. Swim clubs, university facilities, golf clubs– all were still segregated in the mid-1960s.

Despite Chapel Hill’s reputation as a liberal haven in the racist South, the Lees probably expected the town wouldn’t live up to the hype. Howard grew up in Georgia, joined the Army and served in Korea where he, like many other black soldiers from the South, “tasted freedom.” As he told Stasio: “When you taste freedom and then you lose it again, that’s a tough pill to swallow. So when I came back from Korea and settled in as a probation officer in Savannah, Georgia, I found myself right back in the oppressive, discriminatory environment where I was paid a hundred dollars less than my white counterparts in the juvenile justice system.”

What defined Lee’s fight for equality was his commitment to not racialize the issue directly, but to work within the system, using his position to advocate and act on behalf of those the system cheated. Another part of the “Lee Way” was to recognize the various forms oppression can take; in his experience, poor and working class white kids in Savannah also suffered disadvantages. Speaking of Savannah, Lee recalled: “We lived next door to whites. We got along well. … But the difference was during that day was white families thought they were better than black families and didn’t accept that they were being treated just as poorly. Today it’s even worse.”

Lee saw the parallels when he moved to Chapel Hill where he recognized the plight of most of the white kids in mostly working class, or as many saw it, “redneck” Carrboro. And yet it was in the black neighborhoods that city street paving, maintenance, sewer and water stopped.

In 1968, when he decided to run for mayor of Chapel Hill, only one-fifth of one percent of public officials in the US was black. Lee opponent was a liberal Democrat. But Lee did not back down; he wanted to make sure desegregation progressed and put it at the top of his agenda.

Lee, I think, was enticed by the challenge and had a vision for how African Americans and other disenfranchised groups could challenge systemic injustices and gain power within the local political system: “We organized Chapel Hill like it had never been organized before by using students from the university and faculty and also bringing students in from around the state using somewhat of a civil rights tactic of getting people to come from the outside to help us on the inside.”

For Lee, his campaign wasn’t about race. It was about fairness and empowerment. And it was about educating African Americans on the power they could wield in a democracy when they were organized and informed. One local activist, Edwin Caldwell, whose family members had been at the forefront of the local civil rights movement, gives a moving and powerful account of the way the Lee campaign worked “on the ground” on election day: “We would say, ‘Look, who are you going to vote for?’ ‘Well you know I’m going to let the Lord.’ I said, ‘No, we ain’t going to let the Lord choose today. You take this piece of paper; this is who you vote for. You let the Lord choose some other day.’ So we pretty much told them who to vote for. We controlled things. They went in there and they came out and people were proud. You talking about South Africa and voting, people were voting in Chapel Hill and they were proud the same way. You could just see their backs straighten up and see how proud they were. I worked the streets until the polls closed; we got every vote that we could find. We almost wrestled some people in that didn’t want to go, but once they went and voted they were proud.”

There is a strong commitment to democracy and justice in this liberal town. It’s just not among those folks who most often take credit for it. Howard Lee’s election is more a story of what it took for Blacks to overcome the many obstacles to equality here than a story of white liberal progressivism. Today--fifty years later--voting rights are under renewed attack, challenged by proposed restrictions and racial gerrymandering. Community members gathered yesterday at Hargraves Center in Northside to discuss what can be done to oppose redistricting plans that would split a district surrounding NC A&T that would effectively split a majority African-American area into two minority constituencies.

Mr. Caldwell’s words remind us of the importance of hard-fought voting rights and of continuing the struggle to uphold them.

0 notes

Text

Time to Reunite! The Tenth Annual Northside Festival is just around the corner!!!

What is the Northside Festival?

It’s not an information fair. It’s not an amusement park. It’s not a market. Nothing’s for sale. Everything’s free—and everybody’s free. Nobody can afford what anyone else can’t and everybody’s everybody.

The Northside Festival renews the end-of-year festivities at Orange County Training School, the Black school that used to stand on the ground of the new Northside Elementary. The May Pole ribbons will be flying. Kids of ALL ages are invited to join in old-school potato sack and 3-legged races.

It’s a union and reunion. Whether your cousins or teachers lived in Northside homes, or you’ve just moved in, or you worship at one of our pillar churches, or you have a friend who has done a, b, or c, or you’ve just heard how great this neighborhood is and always has been: join us! Come dance in the street, play Spades, feast. Re-unite!

It’s a celebration of gifts. You will be knocked out by our local talent—Bubba Norwood on drums, the amazing Jr. Weaver Gospel Singers, the CEF Advocacy Choir offering yet more of its ingenious adaptations of popular songs in support of affordable housing.

And it’s an anniversary! The Marian Cheek Jackson Center and the Community Empowerment Fund are each celebrating 10 years in community. What a joy. To mark the day, we’re hosting the Rev. Troy F. Harrison Honorary Pig Pickin’—with the help of our friends at the Parrish Brothers farm. Your plate is waiting.

Great music, great food, great people. In the end, the Festival is about being together in the face of everything that would keep us apart.

I can’t wait to see you.

--Della Pollock

It’s a Parrish Brothers Pig Pickin’ in Honor of Rev. Harrison

We are blessed to be partnering with the Parrish Brothers, Melvin & David, to host the Rev. Troy F. Harrison Honorary Pig Pickin' at the Northside Festival. The Parrish Brothers are known for their beautiful worship services, their delicious bbq, their generous spirits, their deep faith & dedication to their land.

For years, Parrish Bros Farm has partnered with Heavenly Groceries to eliminate food waste and create a better food system. They continue to own and operate one of the longest standing black-owned farms in Orange County. The Parrish family has had a role in building and sustaining every part of Chapel Hill/Carrboro.

If you haven't been lucky enough to have their barbecue, you may remember their sister Louise' famous pies & pound cakes at the Carrboro Farmer's Market. Regardless, you won't want to miss this - 150 lbs of delicious, local hog!

And don't worry. If you don't eat pork, we'll have a wide variety of food for you too. We’re proud to share the best food yet in honor of Rev Troy Harrison, former pastor at St. Joseph, co-founder of the Marian Cheek Jackson Center, and low-country chef supreme.

--Hudson Vaughan

0 notes

Text

Stories that move us

Stories. What are the stories we tell? What are the stories that nourish us? What are the stories that remind us of who we are? What we stand for? What generations have stood for?

Shared over a meal.

Sung in praise. And sorrow. And defiance.

Carried through movement.

That inspire movement.

Lately, the MCJC – the Marian Cheek Jackson Center for Saving and Making History – has been reflecting on its own story. Looking at the past to understand the present. Looking at the spirit and the charge behind its name. Looking at missteps and triumphs. Looking to see where this organization, that breathes and bleeds and loves and questions and is imperfect and sincere, will go. And how it will carry forth a vision born from and seeking the Beloved Community.

I’m fairly new here (y’all reading this may be wondering who I am and why I’m writing this) and am still learning about this organization and its place in the community. But, (with permission), I want to share with you a condensed version MCJC’s Basic Operating Principles (aka “what’s in that secret sauce?”) – which moved me to be folded into the mix.

1. Listen. Then listen again. Then listen again. Listen to be changed. Listen to witness.

2. Respond. Assume response-ability. [1] Understand oral histories as a call to action.

3. Work beyond an oppositional politics. Focus on what we’re for… focus on building connections, partnerships, and “matchmaking” of all kinds.

4. Beware of best intentions. Check your enthusiasms against those of community members. Ask.

5. Refuse to represent. We can and must listen forward into community justice… Remember that “Northside” is broadly, wonderfully heterogeneous.

6. Celebrate. As a primary way of recognizing personhood, declaring peace, renewing spirit, making necessary connections, honoring accomplishments… be present to abundance in the moment.

7. Cultivate an ethnographic spirit. Wonder: a. rapt attention or astonishment at something awesomely mysterious or new to one’s experience. b. a feeling of doubt or uncertainty. Claim both.

8. Criss-cross differences. Consider what if

9. Assume the Right to be Raggedy (title credit: Jasmine “Juice” Farmer) To be responsive means to be in process.

10. Practice Gratitude. For many reasons but mostly because our neighborhood compatriots model it daily—and because we get to work with them.

11. If all else fails, go back to #1.

I share these as a reflection of part of the MCJC’s story and as a call to hold the MCJC accountable to what it aspires to do and be. In this work, there is always room for feedback and self-examination to help remind, clarify, and strengthen the who and the why.

So, to go back to the question of “what is the story of the MCJC?”, one might simply be boiled down to:

Someone shared their story. Somebody listened and was changed.

But, there’s never just one story. What are your stories of the Marian Cheek Jackson Center?

How can we thrive in the multitude?

Yours in joy, in peace, in love, in reckoning.

Submitted by Kaley Deal, February 2019

[1] Kelly Oliver, Witnessing: Beyond Recognition (University of Minnesota Press, 2001)

0 notes

Text

Crossing the Tracks: Ronnie Bynum talks about his childhood in Carrboro

Ronnie Bynum remembers what it was like to be one of the first black students at Carrboro Elementary. At an evening event in late November, Ronnie told an audience of students, teachers, and parents in the Carrboro Elementary school auditorium the stories he remembers from those days. In the mid-1960s, the Chapel Hill-Carrboro City school district had just begun the desegregation process, and some Klansmen from Carrboro decided to direct their anger against elementary school students. Whenever he left his house on Street and got on the school bus, Ronnie feared the worst. Instead of stopping in front of the school, the bus driver would stop a distance away from the entrance where a group of local Klansmen would be waiting. “They would chase me into the school every day; and they would be waiting when we got out.” They taunted and threatened him. At this time, Klan members were burning crosses on lawns and holding very public rallies, terrorizing residents and threatening people who challenged segregation and Jim Crow laws.

His best friend, he said, was a white boy, the son of a Klan member, who defied his parents and played with Ronnie at school and at the Bynum home even though they could not acknowledge each other in public. As Ronnie explained it, “If his father had known about our friendship, he would have beat his son.”

Fellow students often were allies when teachers overlooked him. Ronnie told the audience how a teacher refused to call on him in class when he had his hand raised, even after other students noticed and tried to point out Ronnie. When he told his grandmother stories about what was happening in the classroom, she asked him where he was sitting. When he said he liked to sit in the back, she had some advice for him that he has never forgotten: “My grandmother taught me if I ever wanted to be recognized, be in the front. Be the best you can be.”

After a lively question and answer session, current elementary school students were asked to design freedom signs reflecting messages they would have liked the young Ronnie to see. Among the messages were “Everyone is welcome here.” “The secret of happiness is freedom. The secret of freedom is courage.” The evening concluded when they carried their signs, chanting, around the school.

0 notes

Text

Voice, Choice and the Meaning of Freedom

By Trey Walk, Jackson Center Northside Neighborhood Initiative (NNI) Intern

Ms. Clem Self speaks to CHCCS principals during a Freedom Tour, 9 October 9 2018

This October, a group of twenty principals from local schools visited the Marian Cheek Jackson Center and found themselves immersed in the social justice tradition of the Northside neighborhood.

I stood with Kari, another MCJC intern, beside the historic Hargraves Center and watched as the principals gathered around to hear neighborhood civil rights history from Ms. Clementine Self, who grew up in Northside and is featured in a Jim Wallace photo of the Chapel Rights civil rights movement that hangs in the National Museum of African-American History and Culture in Washington, DC. Their group, diverse in age, race, and gender, listened with fascination as she spoke of the brave young people who strategized sit-ins and marches. She spoke of the community that raised them, and the heartbeat they left behind that still can be felt pumping in Northside today.

Kari, myself, and the rest of the MCJC staff instructed the principals to make Freedom Signs with the posters, bright scented markers, and stickers we had laid out on the picnic tables. This is an activity our education team and community mentors have led dozens of Chapel Hill and Carrboro students through. We give them a poster board and marker and instruct them to make a sign with the simple prompt, “What does freedom look like to you?”

The activity, short and simple, is powerful and demanding. We asked the principals, and the students and this community, to imagine a more just world. We are asking them to put language to what freedom looks like. We are asking them to think about the beloved community, and how we might get there.

The principals eagerly made the signs with lots of colors and stickers. Next, they marched up Roberson Street to St. Joseph’s CME where they sang freedom songs.

“Ain’t gonna let nobody turn me around

Turn me around

Turn me around

Ain’t gonna let nobody turn me around

Turn me around

I’m gonna keep on walkin’

Keep on talkin’

Marching into freedom land”

Before the principals left, Kari and I went around cleaning up materials and reading their signs. I couldn’t help but notice many of them said the same words: “choice” and “voice.”

These are both words that are loaded in contemporary debates around education reform, so it is interesting that the principals believe both choice and voice play a role in freedom. Reflecting on this pattern, a series of questions emerged. What does it mean for African American families, whose schooling needs have been historically neglected, to have meaningful choice when it comes to schooling for their children? In Chapel Hill, where the achievement gap is central in conversations about education reform, what role might voice and choice play in creating a more fair system?

I don’t intend to weigh in on ongoing debates that are beyond my experience and expertise. I do hope to ask hard questions about the different interpretations of the freedom signs made on that day. I wondered, reading the signs, if we all mean the same things when we say “choice” and “voice.” Maybe we are using the same words, but mean different things.

Northside has long been a community of builders, educators, and freedom fighters. As we think about our schools and what might be a more just education system for the children in this neighborhood, we have to find ways to come to consensus on what freedom looks like for us. As principals, parents, and neighbors think about the future of Chapel Hill-Carrboro City schools, we must remember that the Northside freedom fighters and students showed us the way. Imagination is one of the gifts they passed down to this community. In the words of Miss Ella Baker, a civil rights organizer and educator: “We have to find out who we are, where we have come from, and where we are going.”

0 notes

Text

Porch Revival on Graham Street

Adante, Preman, and Tia welcomed their Northside neighbors

Adante

To me, hosting the porch party was my official introduction to the neighborhood. Though my housemates and I met a few of my neighbors in passing and in previous neighborhood gatherings, I found a party with food, drinks and music to be the perfect way to say, "Hey, we're here!" Having been to another porch party in the neighborhood I was excited for the opportunity to host my neighbors this time...but I was also nervous. There were a couple of reasons for that.

First, the forecast called for severe thunderstorms during the time of our party. Imagine constantly checking the weather app on your phone to see if the clouds and lightning bolts would disappear off the screen! That was me. I was worried that this party, with all of the publicity and planning that went into it, would get cancelled (even though in reality would have likely been postponed).

I was also nervous because of the responsibility that comes with being a host, specifically the pressure to deliver and impress. A host must ensure that guests feel welcome and are having a good time. For me, that meant making sure the house was clean, cooking and serving food that everyone could eat, and playing music that wouldn't offend anyone or deter anyone from stopping by. Also, living in a neighborhood comprised of students, young professionals and longtime residents of varying ages, races and genders means that you can't just cater to one particular group. That fact alone added even more pressure to deliver a quality experience that everyone could enjoy. I certainly didn't want this event to be the talk of the neighborhood for all the wrong reasons.

Thankfully, that was not the case, as the weather held up and people came and enjoyed themselves. The pressure and nervousness slowly dissipated with each person that set foot in the yard. It was refreshing to see the dialogues between students and longtime residents, teenagers and elders, known neighbors and newly-introduced neighbors, and any other group represented in Northside take place on our front yard that evening.

We are living in a dark time in which political tension, xenophobia, and divisiveness plague our country, a time in which our differences become the center of debate and reactants for vitriolic products. However, despite all of the negativity, there exist beacons of love, hope, and civility within our country. Beacons which cast light upon the darkness and help us find ways to acknowledge and celebrate our differences. What took place in our yard for those two hours on a September evening convinces me that such a Beacon exists right here in Chapel Hill, in Northside.

Tia

I was extremely nervous about hosting our first porch party. However, walking through our neighborhood and going to each of our neighbors to personally invite them eased my nerves tremendously. Every neighbor (that was home) opened the door with a smile and was extremely inviting and welcoming. By the time, Preman and I got to the end of the street, I felt much better and much more comfortable about the event. On the day of the porch party, I was excited to finally meet everyone! As guests started arriving, the little bit of nervousness that remained completely disappeared, and it simply became neighbors having a great time together. I got to meet neighbors that I hadn’t met at previous neighborhood events and also was excited to see those neighbors and Heavenly Grocery volunteers that I had personally invited. Getting to know everyone on an intimate one-on-one level without pressure or expectations was fantastic and I think the event really showcased what living in Northside is like.

Preman

I immensely enjoyed the porch party. It was wonderful being able to connect with so many people, so quickly. I really didn’t have high hopes for it initially, as many other community events that I had been to in previous neighborhoods that I lived in were not well attended. So it was a happy surprise that so many people came! For me, it was the first time that I felt that Northside could be a real home, a rich community that I could be a part of.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

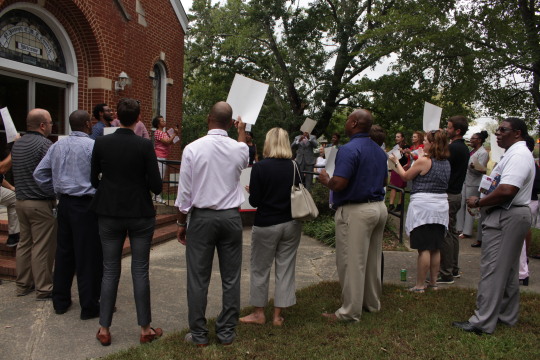

On October 9, 2018, the principals and administrators of the Chapel Hill Carrboro City Schools visited the Jackson Center to learn more about our educational workshops on local civil rights history. They were introduced to our Freedom Walk workshop, starting out at the Freedom Fighters Gateway, then heading to Hargraves Center where they learned about the Navy B1 Band and life in segregated Chapel Hill from civil rights movement veteran, Clementine Self, whose photo hangs in the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, DC (see below).

Principals made their own freedom signs, then marched down Roberson to the front steps of St. Joseph’s CME Church, launching ground of the Chapel Hill freedom movement (see below). As Reverend Robert Campbell, who grew up in Northside, once said: “You can stand on the side of the church or you can stand in the back of the church. But if you really want to make white people nervous, you gather in front of the church!” The workshop concluded with an old freedom song:

Ain’t gonna let nobody turn me around, turn me around, turn me around.

Ain’t gonna let nobody turn me around.

I’m gonna keep on walking, keep on talking, marching down freedom way.

0 notes

Text

WHEN THE CONFEDERACY LOST CHAPEL HILL

By Mike Ogle

Mary Anngady was a girl the last time the Confederacy lost Chapel Hill. She lived in quarters behind the Davis house with a dozen enslaved people, including her mother and four brothers. Franklin Davis, owner of so much, ran a small-town general store. In the main house, Bettie Davis and her children drilled Mary on “courtesy and respect” for her “superiors.” Many days, Mary would “scrap” with her brother over who got to rub Bettie’s feet. Mary hoped to be allowed to sleep at those feet at night.

Mary recalled much from her childhood for the “Slave Narratives” collected by the Federal Writers’ Project in the 1930s. She also remembered well the moment she learned she was free. “The first I knew of the Yankees was when I was out in my marster’s yard picking up chips and they came along, took my little brother and put him on a horse’s back and carried him up town,” she said. “I ran and told my mother about it. They rode brother over the town a while, having fun out of him, then they brought him back. Brother said he had a good ride… .” The Union soldiers took food from Franklin’s store and gave Mary’s father, James Mason, owned by another family, some crackers and meat. James chastised them for stealing. Mary later went to college.

White families passed down for generations melancholy tales from that period here starting when Union soldiers rode into town on Easter in 1865. Meanwhile, the stories of people like Mary were broadly ignored. That whitewashing occurred despite the fact that 4 in 10 Chapel Hillians were enslaved around the start of the Civil War, and about half the town was black, according to Yonni Chapman’s doctoral dissertation, “Black Freedom and the University of North Carolina, 1793-1860.”

The appearance of those blue uniforms coming uphill on a dirt road symbolized a lot more than the loss of a war. Those soldiers’ arrival meant the hierarchy that was the Confederacy’s “cornerstone”—as its vice president called it—was eroding. In 2018, the Confederacy has been riding back into Chapel Hill. Its modern supporters are also upset over something lost: Silent Sam. But the Confederate statue had always signified something much more than lives lost at battle. Like those Federal troops, Silent Sam was a symbol of the lives its admirers had lost ownership of and still aimed to control.

Until the war was lost, UNC, America’s oldest public university, had been a place for educating and strengthening the slaveholding class. By 1860, North Carolina’s legislature had a higher percentage (85) of politicians owning human beings than any statehouse in the country, according to Many Excellent People: Power and Privilege in North Carolina, 1850-1900. So many of the college town’s white men volunteered for the local infantry that within weeks of the war’s start only a few dozen able-bodied ones remained. So many UNC students immediately traded books for rifles that UNC’s president, David L. Swain, wrote begging that North Carolina’s elite sons complete their coursework and contribute to the cause in other ways.

In a well-worn story from shortly after the war’s end, the Federal general occupying Chapel Hill married the college president’s daughter. White Chapel Hillians were said to have spit on invitations, and students hanged Swain and his new son-in-law in effigy. It was in this environment that Julian Carr “horse-whipped a Negro wench,” as he bragged at Silent Sam’s 1913 dedication.

African Americans sent a lovely cake for the wedding, but Swain didn’t let the Yankee addition to his family weaken his allegiance to white supremacy. He had owned 32 enslaved people before the war, and when occupying Union forces banned whipping after it, Swain and two UNC trustees went to ask the U.S. president to reinstate legal beatings.

Before emancipation, Nellie Strayhorn’s owner once whipped her for biting an apple too fresh off the tree. Nellie was 14 when the war ended, and while enslaved on Wesley and Julie Atwater’s farm, she’d “ploughed same as a man,” Nellie recalled years later. Wesley joined the Confederate Army, and Nellie’s mother was made to cook barrels of food for troops fighting to keep her family as chattel.

Nellie’s words were reprinted in a book commemorating Chapel Hill’s 1993 bicentennial titled Chapel Hill: 200 Years “Close to Magic.” Her story appeared under a section called “Reminisces of Slavery Days.” Nearly 80 years after those days, like Mary Anngady, Nellie had also vividly remembered in her original interview the moment she gained freedom. She had been laboring with her mother when Union soldiers approached. “… All the hands was in the field, just like Master was there,” Nellie said. “Dey asked Mother if she knew we was free. She said, ‘No, Sir,’ and I was standin’ beside her when she said it. ‘We fought to free you,’ dey told her.”

With that new freedom, formerly enslaved people all over the South, Chapel Hill included, searched for loved ones lost on the auction block. Yet generations of white Chapel Hillians mournfully remembered this era for having been pulled down off their pedestal.

Bitterness over the demotion eventually led UNC to close for four years, and Cornelia Phillips Spencer paved the way for its reopening under leaders of shared Confederate values. To celebrate the triumph, Spencer rang the college bell students had tolled while hanging the father of the bride in effigy. “The whole framework of our social system is dissolved,” she’d written in her diary after the Union arrived. “The negroes are free… .”

Mike Ogle is a journalist who lives near Pine Knolls.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Porch Revival Tour: Lighting the Fire

I felt a small amount of anxiety the day before hosting the June stop of the Porch Revival Tour at my house. Almost everything was in place. The budget for the event determined, supplies calmly resting on my porch, and a buzzing pre-party energy in the neighborhood confirming the word had been making its way around town. However, this lingering weight of doubt wouldn’t leave me alone.

My colleagues Hudson and Brentton, two go-to grill masters who regularly feed the masses, were out of town. The entire week I was hoping a maestro of the grill would appear. No one did. It dawned on me that afternoon that this time the grill master would be me. I have never been the primary person responsible for grilling at a party or event. I usually stand by whomever is grilling and give my sarcastic ESPN play-by-play commentary as if I know what is going on. Now I would be the player subject to the commentary, performing arguably the most key role at a cookout. Let’s just say I was a tad nervous.

It’s crazy how the universe delivers exactly what you need to hear at the most appropriate times, especially when the mind is full of doubt. Ms. Kathy Atwater, lifelong resident of Northside and Jackson Center Community Advocacy Specialist, delivered the message this time on her way out the door at four p.m. Thursday afternoon.

“Did you ever find a grill master?” she asked.

“Nope,” I said. “That’s the one thing I don’t have.”

“Oh well … hot dogs are easy. You can do it.”

Impulsively, I responded, “Yeah … you’re right.” And like that, I was now grill master.

Four p.m. the next day arrived quicker than a summer storm. I snuck into my day several YouTube videos of burley men giving their manly tutorials on grilling tips and strategies. Even though every person had a different process, I picked up enough to have a general idea of what to do and how not to burn myself. I was setting up the last few chairs in the front yard when my neighbor Jim, who lives across the street, came out on his porch and hollered, “You need any help?” Again, I impulsively responded, “Do you know how to work a grill?”

“Is it charcoal?” Jim asked.

“Yeah!”

“Oh yeah, that’s easy” Jim said. I was beginning to see a trend.

He called me over to his porch and gave me the rundown.

He told me to first put the charcoal in-- not too much, but a good amount to get the grill hot, then add lighter fluid and let it sit for a little bit. The key was to light the charcoal with a flaming piece of newspaper and make sure the whole layer gets an even burn. When all the pieces catch--and he assured me they would catch-- he told me just to wait until the coals turned white. That’s when you know it’s nice and hot. Then you can put the grill over the charcoal and put the meat on the grill. The drippings and grease from the meat will drip down on the charcoal and keep the coals hot, he continued, adding that it might be necessary to light the coals again a little later.

He repeated the process to me again to make sure I had gotten it all. (I’m not surprised he did because when I’m intensely processing new information I squint my eyes and open my mouth giving me a dazed and confused countenance.) Then he sent me off to get the grill started.

I gathered the needed materials and dove into the step by step process Jim had explained. By the time I got to lighting the newspaper Jim and Della, MCJC executive director and experienced griller, were standing around me watching, commentating, laughing, and cheerleading. With Jim’s assistance lighting the coals with the burning scrap paper, the black coals began their color transition, and we were in business!

The porch party was a huge success! Over forty of my neighbors came to wind down and fellowship over delicious food and company. I have many memories from hosting, but learning to grill from my neighbor Jim is particularly special. I learned a valuable skill that I will take with me for the rest of my life.

I’m privileged to be a student of Northside. I’m privileged to learn history, values, strategy, creativity, life skills, and most importantly, what it means to be a member of a community. My classroom is not contained within walls. It is not contained by geographic boundaries. My community is the improvisational and boundless university of life, love, faith, and justice.

What will the next lesson be?

--George Barrett, MCJC Associate Director, August 2018

0 notes

Text

In February, we hosted our fifth annual Valentine’s Singing Telegram fundraiser. This year was truly remarkable: we delivered or recorded over 60 singing telegrams in just three days, including 25 generously sponsored songs to Northside neighbors. We raised over $2,000 for critical community-based programming work. And, we had a blast doing it!

Here are just a few glimpses of the fun-raiser: we sang to a professor in the middle of her lecture at NC Central, shocking the students who said, “we’ve never witnessed anything like this.” We surprised two groups of teachers from daycares in town with “You are my sunshine.” We sang three songs to Town Hall staff in front of whole groups of staff gathered. We left an entire bar laughing when we performed “Backstreet Boys” to a couple of embarrassed Jackson Center friends. Our star lead singer, Brentton Harrison created a “love medley” that he delivered to woman in a beauty salon, shocked that her husband even knew where she did her hair and moved by the power of the love songs. And our quartet, the “Jackson Center 4” belted “Ain’t No Mountain High Enough” to a family at dinner in one of Chapel Hill’s largest restaurants. While all of these deliveries were fun, the highlight was delivering songs of “You Are My Sunshine” and “My Girl” to over 20 lifetime neighbors of Northside. Several residents said this was the first time they had ever been serenaded. Others sat and listened with tears streaming down their faces. One sang along. Most said it made their Valentine’s Day so special. We cannot thank our donors/sponsors/neighbors for making this even possible and for making this the best year of singing telegrams so far.

I Want it That Way to, former MSW Intern William Page

youtube

My Girl to Ms. Kathy Kieth Carlotta

youtube

Lead singer Brentton Harrison has written a reflection and poem about this experience below. As he so eloquently says, the most powerful part of the singing telegrams is not that they raise money but that they light up people’s days and build community in a way that is so central to the Jackson Center’s mission. If you have time, check out videos we will post of a few of the fun singing telegrams for this year, and enjoy the reflection from staff member Brentton Harrison below:

At the Jackson Center, we often discuss the goal of “Renewing the Glue.” Well, what does that mean? How can we be part of it? How can we, as a part of this community-minded center of service and advocacy, do this? One way we renew the glue is by offering our gifts to our community in celebration and reminding them that their presence in this community is “the sunshine on a cloudy day” and that they can call on us to say that they’re admired, remembered, respected, and we are following in their legacies to enact selfless love:

To the ladder of synaptic shocks

Books spine cracking for the first time

Networks of love and abundance

To a community where

Smiles lead to wisdom

Lead by the ears of different English

And rhythm’s waves are made

To enter through eyes

And now we stand beside

Time: a defying grace

Never have I ever seen that

played out in the contraction

in the eyes of a community’s

library of memories, stories, and

wise truths broken in the pauses

and the stammerings of the Queens -

Matriarchs, time defies its own

Afflictions and wears standing and sitting

With power beyond sights but

Vibrations shakes out

Gratitude of being thought of,

remembered, and offered a

joyful noise of 3 loud boys

Hearts tender as souffle

Yet there are stuffed beyond

Capacity with humility and

History of our teachers tears

Thump tug and tickle the strings of them

Renewing the glue is the essence of the 5th annual Singing Telegrams fundraiser. We offer ourselves in abundance to those who have taught us this love. It is in this we find abundant love, connection, and a beloved community. Spread love, renew the glue, and keep on singing because you don’t know if your voice can make a difference until you use it. I am also grateful for everyone who gave and made space for us to bring joy, build community, and express abundant love throughout the world and with you.

0 notes