Short essays about about videogames, physics, science fiction, philosophy and other interesting apects of life.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Note

I wonder how many people finished the mod? Personally, I got stumped at three puzzles (the first piece in 3-7 "The Bridge"; the first piece in 5-6 "Agile Companion", and the piece in 5-7 "Closure"). Typically I'd consult a walkthrough at this point, but I can't find any here, nor a way to access the last chapter without completing all preceding puzzles. Do you know of any?

Thanks so much for playing the mod! Unfortunately there are no up-to-date videos that cover all the puzzles -- I want to make a comprehensive walkthrough someday, but haven’t gotten around to it. In the meantime, here are some tips. 3-7 “The Bridge”: If you are having trouble hitting the boss/king goomba on the head with all five chandeliers, it is probably because you are waking him up at the wrong time -- either too early or too late. If you walk by and avoid releasing any chandeliers, so that the goomba king is still asleep, you can climb down the ladder and then walk right up to him, waking him up at the proper moment.

5-6 “Agile Companion”: This puzzle is pretty brutal. I wanted to tune the fireball timing to maybe make it easier, but I couldn’t quite figure out how to do it and didn’t give the issue enough time. Sometimes the key will behave strangely even by Braid standards, glitching out and floating across the screen in a random direction -- this is a bug and not necessary to solve the puzzle. Make sure to keep primary-Tim mostly on the left side of the screen, while shadow-Tim does all the work of ferrying around the key.

5-7 “Closure”: Use repeated ring placement to make sure the goomba retrieves the key and prevent the fireballs from crashing into Tim. Once you have escaped the fireballs, you need to get your ring back so it isn’t stuck on the bottom floor of the puzzle. Then you can use the ring to keep the falling ladder from hitting the floor, and eventually ride the ladder all the way to the final puzzle piece.

I also made a recording with the solution to these three puzzles: https://www.twitch.tv/videos/312354048

Thanks again for playing the mod -- I’m really honored that you’ve played so much of the game! If you’d like, I’d love to hear what you most liked and disliked about More Now Than Ever. I’m not sure how many people have finished the game, but perhaps a very low number, since only a few hundred people have downloaded it and the mod is quite difficult. I tried hard to reduce the platforming challenge and puzzle complexity compared to other Braid mods, but I always knew that it would still be a hopelessly confusing and difficult mess compared to the brilliant puzzles of the original game. But, I hope you have been having a good time!

2 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

To celebrate exactly ten years since the initial release of Braid on August 6, 2008, I am putting out a big new mod called “Braid: More Now Than Ever”. The original game’s time-bending mechanics are further explored via a curated compilation of over 60 of the most surprising, cunning, and elegant puzzles from multiple fan mods (“After the Epilogue”, “Silverbraid”, “Stone”, and “Tim's Modysee”), plus many completely original levels! All-new writing continues the story of Tim and the Princess, paying homage to Braid’s complex structure and themes while also introducing fresh images and new directions. To top it off, remixed art and music create a distinct atmosphere.

You can download “Braid: More Now Than Ever” over at ModDB (of course, you’ll need an installed copy of Braid, too): https://www.moddb.com/mods/more-now-than-ever

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

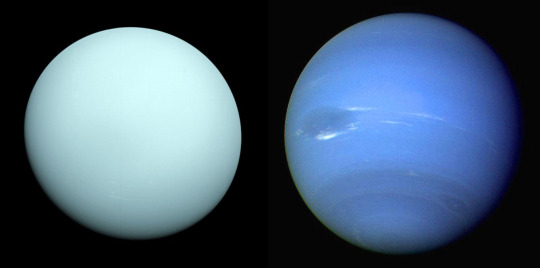

Voyager

This pair of oddballs! Hemispheres of blue, A perfect fit, attached like sea and sky. Such joyful time, to spin and dance with you – Too short, as onwards into night I fly. First up: perceptive, keen, and loyal friend: From her, wild unembellished truths beam forth. This dynamo of wit will whip and bend, 'Till Down is Up, West's East, and South is North. Next: stalwart guardian of this solar set, Without whom all the rest would fling apart. In your pacific depths, a happy debt: To this soft, gentle soul, I owe my heart. I've carried crackling Sounds of Earth for years – But none can match the music of your spheres.

0 notes

Text

Cassini

For many years mine eyes have treasured thee, And lovingly observed your secret ways: The thoughtful depths of your titanic sea, An echo of my sunny homeland's waves. The curves of your soft form – I trace each arc, While tasting ion dust from icy plumes, A hint that you might share that sacred spark I cherish most, from which our lives have bloomed. A jewel among the worlds, adorned by rings, An orb so pure, sweet, elegant, serene. In ballroom orbits, our each step but brings Another yearning through the space between. So far, so long, held back from my desire; I dream of clouds, and ecstasies of fire.

1 note

·

View note

Text

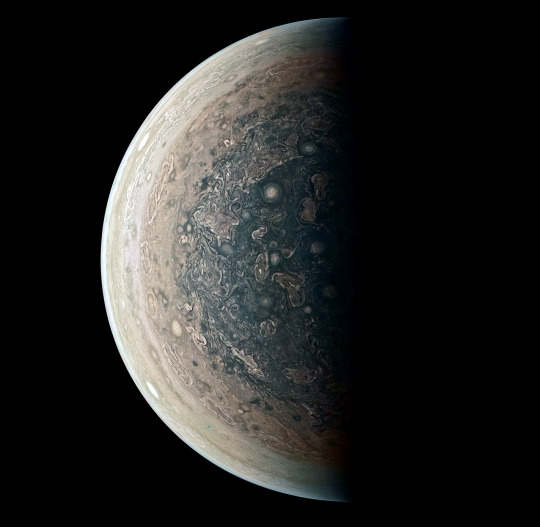

Juno

You, jolly sovereign, and your pantheon, So long have hosted me as grateful guest. A second sun when sunlight's warmth's withdrawn, You radiate with interest, talk, and jest. Such jovial relations might be viewed Like superficial summer evening clouds. But surfaces imply what they occlude: Each signal unearths wisdom 'neath the shroud. Beyond the fractal hues of every band, A diamond mystery, so kind, strong-souled, Vast seas, great mountains, unexplored new land, Which beams forth searing arcs from stoic poles. Now, blinded by the lightning I adore, I tumble, wondering, lost in static's roar.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Ikaros

The Morning Star! Who heralds rising day And, unbeknownst to some, mourns evening's dim. My climb to you began this selfsame way, From waxing East to waning western limb. The gentle pressure of your golden gaze, Has drawn me here, on lustrous wings of foil. Such gorgeous, thoughtful, sensitive display Contrasts the inner clouds that storm and roil. This passion, whirling intellect, and joy – A thriving secret world that few have glimpsed – Astounds this tiny, simple, spinning toy! Alas, our time draws short in this eclipse. Our orbits cross. Then, pushed by sunlight's rays, We've passed, and once more fallen out of phase.

1 note

·

View note

Text

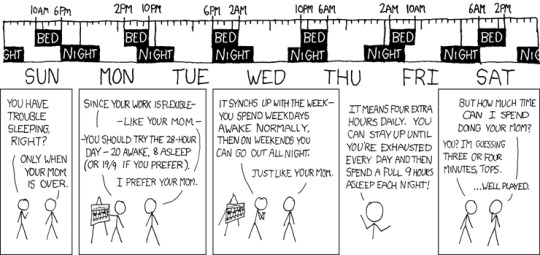

A brief review of the “28-hour day”, also known (semi-ironically) as “The Dymaxion”, brought to you by my final final project in a machine learning class.

pros:

-For some reason, it feels very motivating to plan out your sleep schedules and even fast, easy meals in advance, all optimized around making time to do the work necessary to get some damn project finished. Over this past week I’ve felt less distracted than usual (aka still pretty distracted, but hey), and much more able to just work on stuff for, well, almost literally an entire week straight without losing steam and getting sick of it. Writing down all the hours you have ahead of you between now and the due date, and then watching yourself cross them off one by one, is a very visceral way of reminding you that time is moving forwards and you have to make the best of it. That said, this is also my last week of school ever, which is pretty motivating too, so it’s hard to disentangle those factors. And I’m taking a break right now to write this tumblr post, so there’s that.

-This probably sounds insane, but I’ve actually felt pretty well-rested. Long-term over more than like two days, you can’t cheat your need for sleep, so planning dedicated sleep intervals like a crazed 19th-century utopian progressivist / social-reformist is actually better than my older more classic strategy, which was to just stay up mad late panickedly working on stuff and worry about sleep later. If you plan it out, you realize you’ve gotta give yourself good sleep at least up until the end, when you can make a final push and then recover after the due-date.

-Re: last week of school ever, staying up with crazy sleep schedules just to turn in some huge project is probably not something I’ll be able/forced to do in the future when I’m working, whereas it’s something I’ve done frequently (never before with a week’s worth of premeditation! but I’ve pulled all-nighters and other shenanigans many times) during grad school and college. Thus, it now feels kind of nostalgic and memory-making to be pushing the circadian envelope for (I expect) the last time in a long time.

cons:

-Obviously you can only do this if nobody else is living with you.

-You will not end up going outside much, or cooking much, and it’s uncomfortable to sit at a desk for such a large fraction of one’s waking hours. However, these drawbacks don’t really count since they would be true of any busy person, regardless of their sleep schedule.

-As mentioned earlier, ultimately you still just about need the same quantity of sleep, so you can’t magically get more hours out of the day. The benefits, as outlined above, are more subtle.

-You never really know what time it is, either for the external world (what day it is, hour, etc, even though you’re looking directly at the calendar it just doesn’t really make as much sense) or even for yourself (as in how long you’ve been awake, what meal you are currently on, and what hour this would map onto if you had gotten up at your normal waking-up time instead of like some time in the evening).

-Really weird experience of time generally as being far more continuous and homogeneous than the highly discretized conception of time that human social customs have ingrained in you. This would be a neutral or even positive effect rather than a con, except since you get to consciously experience the time of day that you usually sleep through, nights seem supernaturally long while days are a mere handful of hours. This, combined with the previous bullet point, creates a strong psychological impression of having fallen under the influence of some kind of House of Leaves / Blair Witch style anomaly that is malevolently warping the natural order of the world. On the plus side, respite from this experience is granted every “morning” just after you have woken up: even though you might have just hopped out of bed at 8 PM, you will feel relaxed and energetic and, while the many comforting rituals of morning override any contrary evidence from outside nearby windows, all will seem normal again for another first few hours.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Thoughts in The Mind of Crono Upon His Arrival at The Town of Enhasa in The Empire of Zeal, Having Been Asked The Question, "Do You Believe In Fate?"

Crono remembers having had a thought or two about this kind of thing, back when he was little, long before this whole adventure began. He remembers the ideas which, back then, might have shaped his answer. In those days, Crono had always felt a strong sense of progress. There might be small hiccups now and again, but over the long term things were bound to move forward; it was this steady march which had so clearly brought his kingdom so far in the thousand years since its founding. There was a sense of momentum, of direction to events: the present was unambiguously better than the barbarous past, and the future in turn was sure to be even more prosperous than the present. In a way, Crono supposes, that's a powerful sense of fate.

But on the other hand... fate? As in, everything is part of some secret plan, whole nations and histories just pawns on some cosmic chessboard, events like carefully arranged dominoes, all conspiring towards a predetermined end? It's just too absurd, it's cartoonish. It's so obviously contrary to the ordinary, everyday world of infinite tiny choices and considered, freely-made decisions. Maybe he could talk himself into some subtler definition of fate, but the normal one, the idea that It All Happens For A Reason, that such-and-such was Always Meant To Be... it's myth, it's make-believe. It's just too silly to be true.

But that was the Crono of long ago. It's been barely a few weeks, but it feels like it's been forever. So much has changed: he's seen things he'd never have even imagined, learned things that had been forgotten for millennia. And his companions, five of them now, brought together from every distant corner of the world. Each has their own long and strange story, each their own peculiar perspective. What are they thinking? What would be their answers to the question of fate?

***

Marle started all this, at least in the sense that it was her royal pendant that caused Lucca's machine to generate a time-gate. When it happened, it seemed totally random: Chrono bumped into a girl at the fair, then her strange necklace somehow set off the gate. That first part, at least, wasn't what it seemed: Marle is no ordinary girl, but royalty, in line to become the twenty-eighth Queen of all Guardia! She had disguised herself and left the castle to see the fair without drawing attention, but in a sense her plan backfired: by now she and Chrono and the others have had more dealings with the Guardia royal line than he would ever have guessed possible. Before their adventure began, Marle felt estranged from her parents, her kingdom, and her role as princess. But as they've hopped the centuries between Guardia's past and present, Marle has been a witness to the myriad subtle strands of cause and effect that connect her to her ancestors even thirteen generations distant. She's seen kindness in the 6th century repaid in the 10th, a testament to how values and ideas can persist through the ages. She’s also watched how legacy can twist over time and create unexpected consequences: a criminal justice system established to prevent barbarism becomes a tool of oppression, and a newly-discovered treasure in one age becomes a white elephant that nearly bankrupts the kingdom in another.

But that all happened later. When Marle was thrown for the first time through the portal her pendant created, she was dumped into the Dark Ages. The young princess was mistaken for her distant grandmother, the fourteenth Queen Guardia -- the real queen had gone missing several days ago under mysterious circumstances. Marle's appearance was celebrated by the people: the Queen had been found, so the search was called off. But this meant that the real queen would never be found, preventing Marle from ever being born. Chrono remembers watching it happen: while he and Lucca were talking to her, she slowly began to change, flicker somehow, as erratic motions seemed to tug at different parts of her body. It wasn't her muscles that were jittering, but somehow the world. She could feel it, each twitching tug growing more forceful, like the motion of a spinning top, unstable, about to spin out and tumble over. She screamed, and the scream too was a twitching, flickering, stretched and distorted sound, as she was finally torn out of the universe by the tidal forces of space and time.

What must this have been like? The rest of their party have /seen/ a few changes like this, but to actually experience them -- to know that you are changing, that your existence is racing around a vicious loop of causality, to know that the childhood you remember, the childhood that in this instant you really /had/, is somehow different from the one you had a moment ago. To feel yourself shaped by the past in an infinity of ways, to know with helpless certainty that you are only the inevitable, fated product of that succession of events. But in another sense not inevitable at all -- that you are so fragile, so unstable, that surely nothing could ever be predestined, when the slightest change can throw such chaotic torques into the path of future history!

***

The places they've been to and the things they've seen have been new for everyone -- but especially for Ayla. In her world, nothing was ever new. She lived in a tribal society, millions of years ago. Every day was the same there: the same dangers, the same opportunities, the whole world just a tiny outpost of ignorant humanity in a vast and homogenous jungle landscape. Whole centuries come and go there without much event; any history is first blurred into mumbled myth, then forgotten. Hell, if anybody had asked her about fate before all this started, she probably wouldn't even know what they were talking about. "Fate -- you mean, what do I think about all the stuff that hasn't happened yet? Well of /course/ it's figured out ahead of time, dummy, 'cuz I've already done the figuring: it's gonna be just like all the stuff that's already happened before!"

Indeed, Crono doesn't think her opinion has even changed much in all the time since they met her. Medieval kingdoms, dystopic futures, lost atlantean empires -- to Crono, each era seems dramatically different, their cultures and levels of technology diverging wildly from what he experienced in his own time. But to Ayla, everywhere they've gone has been so unbelievably far from anything she's used to, the different eras might feel equally incomprehensible. Connecting past to future across that vast gulf -- Crono's not even sure if Ayla realizes that these different worlds really are all different parts of her future, rather than just different /places/ somewhere else on the planet. She is happy to help Crono in the fight against Lavos -- but more out of friendship, or in repayment for taking down Azala and the Reptites, than out of concern for her distant descendants. And why should she need to feel such concern? No matter what happens to Guardia Kingdom or the Empire of Zeal, it's all millions of years in the future for her. When this adventure is over, and Ayla returns to Iota villiage, none of these places will have any relevance anymore. She'll go back to living her life --and when it ends, other people will be living other lives little different from hers. And it'll go on and on like that, for thousands and thousands and /thousands/ of generations: the future no different from the past, each day just the same as the one that came before.

***

Lucca is probably the expert opinion here. She opened the first time-gate, after all, even if it was an accident while she was trying to make a teleportation device. Since then, she's spent all her spare time working out equations, trying to figure out as much as possible about how the gates work and what all their time-travel is doing to the world. She has concluded -- well, honestly, most of it is way over Crono's head; Lucca has mostly been talking to Robo lately since he's the only one who can keep up with all the technical stuff. But Crono remembers right before they were about to make the jump into the deep, prehistoric past. He was afraid --they had all been afraid, even if nobody said it-- that whatever they did so many millions of years back, it would probably have huge effects on all future ages. Their families and friends might be totally erased, replaced by an entire alternate history. But then, when they actually did return to the present, that's not at all what they saw. For all they had done --defeating the Reptites, finding enough Dreamstone to repair the Masamune, recruiting Ayla, and saving the whole Iota tribe-- the change in the present was completely undetectable.

All of these time-hopping adventures: to Crono it feels like they occur totally outside the normal bounds of causality, a mischievous meddling in the proper order of events. But Lucca points out that if that was the case, the present should be vastly altered whenever they return from visiting a past age. Instead the differences, if they appear at all, are minor and isolated. She says that the only way this makes sense is if the seemingly original, untouched world we grew up in was actually somehow /already/ altered by our current time-traveling actions. Those actions aren't changing the world but rather in a sense completing it, because somehow the world has /always already been changed by them/. So does this mean some other version of myself has already done the things I'm doing right now? Are there an infinite number of Cronos, each fulfilling the same destiny over and over? This is where Lucca starts to roll her eyes. "I mean /kind of/, I /guess/," she starts, "But really that's totally not the right way to think about it. See, you're still trying to frame things as the result of a normal process of cause-and-effect --made cyclical because of our time-travel, of course, but still decidedly temporal in the ordinary sense. Really it only makes sense to think of the universe stabilizing itself through causal /resonance/ on some unknown extra-temporal level. All of us time-travelers necessarily exist in such a way that our actions are not only self-causing, but also self-stabilizing in the case of variance, and as for how things got this way in the first place? Well, not through any normal process of revision, but instead via some kind of instantaneous extra-temporal harmonic resonance effect. So yeah, no infinite Cronos."

And no fate? On the one hand, unlike most people in Crono's time, Lucca doesn't believe that a god designed the world to follow a special plan. And despite the drama of their adventure, she /definitely/ doesn't believe in fated heroes, days of judgement, or destined battles between good and evil. But on the other hand, she does believe that the universe is "deterministic": if you knew what every particle in the whole world was up to during one particular instant, you'd be able to predict their future movement and interactions perfectly, so you'd know exactly what the whole future would be like. How did the particles happen to get like that, rather than being in some other configuration? Well, Lucca says that the world went through some kind of "extra-temporal settling process" of "self-stabilizing resonance," which means our particular history is "cradled in some low-energy configuration: at least a local, or possibly global minimum within possibility-space." Deterministic history -- that means the future's inevitable -- settled into a stabilizing minimum -- that means things couldn't have happened any other way. Lucca might not call that fate, but to Crono it at least sounds pretty similar.

***

Frog... Frog is a strange one. For Crono and everyone else, their quest through history has not just been an incredible, unexpected adventure -- it has also given them a big change in perspective. Crono mostly doesn't think about this, distracted as he usually is by the drama and romance of his mission, the thrill of battle and the intrepid courage of exploration: knowing a heroic epic when he sees one, Crono is all too eager to play his part. But on those rare occasions when he does step back and consider it all... it's like suddenly he's way out in space, looking down at his faraway home while watching whole oceans spin by. Seeing so many lives come and go, seeing the river of history bend and meander across changing eons -- it forces a certain detachment.

But Frog isn't like that. After all this change, all this adventure, he's still just the honorable knight, seeking only to fulfill his duty to his liege. To Crono it seems a little ridiculous -- like how could you still care about all that little stuff, after how far we've come? You might start to suspect that Frog was clinging onto his knightly duties for dear life, the one thing grounding him to the backwards era from which he hails. Or hey, maybe he's just stupid.

Except it's obvious he's not. Frog might've been born in the Dark Ages, but still it's clear he's more thoughtful than Crono and all the other humans in their party put together. Crono's seen him: how he always volunteers to keep watch over the rest of the camp, how he takes lots of time alone just polishing his armor, sharpening the Masamune. Frog is quiet, soft-spoken, but he's thinking in every moment. Crono can tell: when Frog has that faraway look, he's not just reminiscing about his days back in Guardia Kingdom. No, he's going over everything they've seen so far, figuring things out, putting the pieces together better than anyone.

So, from Frog's point of view, what picture do those pieces make?

For a long time, Frog thought Magus and his shadowy forces were the ultimate evil. But in a twist, he discovered that Magus had only been doing what he felt he had to --he had raised up his army, enslaved half of Guardia, tried to dominate the globe-- in a desperate bid to build his strength to summon and defeat a far greater destructive force, the monster Lavos. Stopping Magus might've bought Guardia some time, but it's doomed as long as Lavos still exists. So joining Crono is really just another part of his duty to the kingdom, another chapter in a knight's story. And it really /is/ a story: to Crono all the fairy-tale stuff seems absurd, dark wizards raising goblin armies and lost princesses rescued by valiant knights cursed into animal form. Even though it's real it still seems made-up, and there's the question, really. So Frog is playing a part in an old fantasy tale, he even realizes this -- surely he notices that to everyone else all the chivalry stuff looks like theatre. But is he acting by nature, or by choice? Back before Crono had pieced together the Masamune... Frog was living alone in the forest, he had lost faith in himself, he felt he was an imposter, living in Cyrus's shadow. Cyrus was the destined hero, but he was killed, and Frog was failing in his attempts to fill that void and save the kingdom himself.

Now he's succeeded: eventually he did take the legendary Masamune, and used it to defeat Magus in the dark tower. So now Frog feels a lot better about himself, but what does he think of fate? "Cyrus had fate, but I did not. He was fated to defeat Magus, but failed. Instead, with thine aid, I succeeded. Impossible, thou might say: if thy were the one who saved the kingdom, then /thy/ must have been the fated hero. Yet somehow I know that is not the correct interpretation. Perhaps mine was rather to inherit a destiny that by rights belonged to him? I cannot say." Fated to defy fate, destined to give off the mere appearance of destiny? Or maybe there is no real destiny, yet if Frog believed in destiny it was inevitable that he would find a way to defeat Magus? Is an imposter-hero still an imposter if he has perfectly filled the role? Is it only his own attitude towards his actions that holds him back from becoming the true knight that others see in him -- and if so, one must ask, can a sufficiently skilled actor hope to transform himself into the character he imitates? Crono wonders if these are some of the questions Frog has already been asking of himself, in all those quiet moments.

***

Robo's journey has been longer and stranger than any of the others'. Created as R66-Y by the Mother Brain of Geno Dome's automated factory, Robo was originally designed for the sole purpose of bringing Mother Brain's electric dream into reality: the last fragments of humanity overpowered, the world remade as a robot utopia of logic and steel. Then as now, Robo's decisions were made freely by his own mind, acted out by his own will. But what does it mean to be free, if your very mind was moulded by another's hand?

To live with a pre-programmed mind sounds horrid to Crono -- until he considers his own circumstances. His parents, his friends, the culture and country and class and era of his birth, beyond that the impact of heredity and evolution, a chain of cause and effect stretching back millions of years, all the way back to Ayla, and beyond! At least Robo could hope to list the forces that had a hand in his genesis; Crono would never have a chance to fully comprehend the myriad influences on his identity.

But Robo's premeditated destiny was not to be fulfilled -- he broke down in Proto Dome, and lay there inert for decades until Lucca repaired and reprogrammed him. Since then he's been living and adventuring with Crono, Lucca, and the rest. He's made friends with everyone, and -- though he joined their party merely out of gratitude for Lucca's repair work -- Robo is now as dedicated as anyone to stopping Lavos and /saving/ humanity. Crono assumed that he was watching a change of heart -- but was it really just a change of circuitry? Think back to when they visited Geno Dome: the other automatons called him defective, they said that his mind had been subverted, that he had forgotten his true purpose. Robo opposed them: he said he had not been subverted, but had merely traveled and seen farther than they -- that it was new data, not new programming, which was responsible for his new behavior.

Why is the one respected, the other despised? It's wonderful to "change one's mind" after some new experience or re-consideration... but to /be/ changed? To alter the very method of one's thinking and not merely the content of one's beliefs? That's a different matter -- indeed, it might even be a different person. In Robo, Crono can't help thinking that a change caused by new data is somehow more real, more genuine, more /earned/, than a change caused by new programming. But in fellow humans, it's different: to have a "transformative experience," to be a "changed man," for humans the deepest and most meaningful changes are closer to changes in programming. To alter opinion and behavior based only on new data is weak, shallow -- mere flip-flopping.

And were Robo's words even true that day? Crono knows that he /had/ been reprogrammed, modified at least slightly. During her repairs, Lucca removed Mother Brain's instructions, she said: that way, Robo would not harm us. When she did that, was she restoring Robo's true self, reversing the pathology that Mother Brain had injected into the robots coming off her assembly lines? But the robots at Geno Dome weren't mindless or insane -- they were perfectly rational beings, albeit with some built-in predisposition towards a radical ideology. By what metric do we judge Robo's mind superior to those of Mother's minions? Perhaps it is impossible to speak of a "true self"; could it be that the thought of "repairing" a personality is, fundamentally, an absurdity?

When they confronted Mother Brain -- her menacing, holographic image flickered and sheared across the monitors like reflections in a shattered mirror -- she claimed to reveal Robo's secret, his special mission. She said he was a custom design, programmed to live like a spy among the humans and attempt to befriend them, the better to record and analyze their strengths and weaknesses, to understand the way they think.

Was she telling the truth? There's every chance that Mother's programming ran far deeper and more subtle than what Lucca thought she saw. But if Mother Brain's programming survives inside Robo, then what Robo had seen of the outside world really was able to change him, because he opposed her boldly and without hesitation.

Or was it really just a desperate lie, an attempt to sow suspicion among their party and win Robo back to her side? If so, the ploy failed to save her -- but it did not fail to demonstrate that she had developed a keen understanding of human psychology. For a long time after Geno Dome, Crono had watched Robo very closely. He had wanted to trust Robo, he /knew/ that he had changed -- but somewhere in the back of his mind, Crono couldn't shake off the suspicion. For days after her death, thanks to those comments, Mother Brain had ruled a part of Chrono's thoughts, making him fear that she might also be ruling a part of Robo's. Maybe that's the secret: for her, reprogramming wasn't even necessary to gain control. Understand the program well enough, feed it the right data, and you can control the outputs without ever influencing its internal operations. Maybe that's what fate really looks like, when you see it up close.

And to defy fate? Control the inputs, perhaps, to achieve the outputs /you/ desire. But of course, those desires are merely the outputs of past cycles. In that case, iterate: take the old outputs and use them as inputs for the next cycle. You'll certainly go somewhere, but how do you know if you started in the right place, and how do you tell when you're headed in the right direction?

Ask Robo -- he's put in more cycles than anyone. Growing up, Crono had often heard the legend about Fiona, the woman who died in the middle ages trying to protect the forest near her home from Magus's armies. After we had traveled to that time, stopped Magus, and actually met Fiona, Robo volunteered to stay behind and help her cultivate the fledgling woods. Crono left him there, and zipped forward to 1000 AD -- in total, only a few hours for Crono and the other humans, but /four hundred years/ for their mechanical friend. Working day after day, living alone like a hermit, in those many lifetimes he had turned the entire southern desert into a lush expanse of woodlands. They found his broken-down body preserved in a cathedral, venerated as a holy relic by those who came to celebrate the forest. When Lucca had finished rebuilding him for the second time, he told them his story -- the things he had learned, the paths he had walked in his wandering thoughts, as the eons slipped by. He told of how, in his million hours of lonesome thought, many seemingly complicated things revealing themselves as simple and clear; other, seemingly simple things unfold into complex uncertainties. And he spoke of a puzzle which he had turned over in his mind for all those years.

It is possible to generate time-gates artificially, but apart from the one first spawned by Lucca's experiment at the fair, all the gates they have encountered appear to have generated spontaneously and randomly, as if by some natural process. And yet, many of these gates link to moments of extreme significance in the history of civilization, of Lavos, and of the planet as a whole. Robo says that over the eons, he has sensed the presence of what he called "an Entity," a conscious influence that may be using the gates, perhaps using even this very adventure, as a way of coming into being, of experiencing or re-experiencing the critical moments of its own existence -- like how a dying man might see a vision of his life just before his death. The nature of this Entity, if it even exists, is a total mystery. But if a conscious force is alive and at work in the world in this way -- if there is some invisible world-spirit guiding them, leading them on this tour through time, preparing them for their inevitable confrontation with Lavos -- then Fate is surely the only word we could use to describe it.

But on the other hand, here's Robo: an electronic automaton from the far future, designed originally by man, modified and manufactured to be a soldier for Mother Brain's utopia, broken down for decades far from home, repaired and reprogrammed by Lucca to join an incredible adventure across thousands of years, finally a lonesome forest guardian, lost in thought for centuries, revered as a saint from a long-ago age... who would deny that such a being has transcended anything that fate might've had in mind?

***

Crono ponders all these things as he considers his answer. It’s strange how important it feels to get this one right: this single conversation, not even a conversation -- barely even a sentence! A yes or a no, lost in the whirlwind of history, the epic sweep of their grand adventure. A single uncertain note, set adrift in the dream-land empire of Zeal.

But Crono knows how small movements can have lasting, meaningful effects later on. Time can be a lever, magnifying the force of your actions with a fulcrum of centuries. Consequences percolate down the ages, building momentum across great valleys of time, shaping the world in powerful but often unexpected ways. Are these avalanches an artifact of intention, or an expression of destiny?

His own story has certainly snowballed. It didn’t start with a grand initiation or kingly assignment, only a trip to the fair. Then he was helping Lucca, then they were rescuing Marle, then they were stopping Magus, then tracking down and trying to put an end to Lavos.

Crono didn’t inherit the role of hero, but like Frog, he has taken it on himself. Doe this mean defeating Lavos is his destiny? Just because he has lead the charge on a heroic quest doesn’t mean his actions were meant-to-be. After all, how can something be fate if you’re doing it of your own volition? Chrono chose this path freely, every step of the way.

But did he really? Robo made a choice to turn against his creator, Mother Brain, and help to redeem humanity rather than destroy it. But Robo’s thoughts are pure clockwork, bound by a program forged by Mother Brain and modified by Lucca. And if Lucca's right about the whole universe being deterministic, that means his own mind is really no different from Robo's.

Throughout these eons, Crono has been taunted by the sight of the same tragic scenes repeating over and over: people just keep making the same predictable choices, basic human tendencies keep asserting themselves. Empires rising and falling, a parade of blind tyrants making the same mistakes over and over, trying to take advantage of a dark power they could never comprehend. Like Crono, these despots might see themselves choosing freely every step of the way. But from the outside it all seems so inevitable, so mindless.

Amid these cycles of destruction, Chrono finds it hard to conceive of any intervention that could meaningfully disrupt --or escape!-- these devastating rhythms, rather than merely warping the timbre of individual details.

Why do we fall into this trap? How did Lavos become the resonant frequency of civilization? If these people could see the whole sweep of things, Chrono imagines, could see how many had gone before and how many would go after, then maybe they'd change, maybe they'd be able to stop. So maybe one kind of fate is just lack of knowledge -- these tyrants, they're fated to their foolish actions only because they can't see far enough to understand the consequences. And maybe if you can see the consequences, then you can choose more wisely, and defy your fate.

Is that what Magus was trying to do? Crono will never forget the image of that great wizard, standing alone in the darkness at the top of the world.

Crono knows he sees farther than the tyrants. But can he ever see far enough to change his own destiny? Lucca would remind him that his adventures through time provide no special advantage here: he can peek forward only to the dystopic, devastated future that will occur if he doesn't try to prevent the apocalypse -- it gives no indication of whether he will be successful if he does. (Or maybe, if Lucca's always-already-altered theory is correct, then it does give indication -- that they've already failed. Lucca says it's complicated: some things, even big things like the new forest, can change, while others --like Marle's identity as Princess of Guardia-- cannot.)

He remembers Robo's ideas about the Entity. Compared to that Entity, he surely knows nothing. He might be travelling through time, but he’ll never have the whole picture, and he doesn't have any special insight into the ultimate outcomes of his own actions. He can try to make things better for the people of Guardia, and maybe too for the people of Arris Dome, but who can guess what happens a million years from now? It’s as unknowable to him as his time is to a member of Ayla’s village.

As thoughts rush through his mind, he feels like Marle must have felt, in that moment back in Guardia castle. He’s not just torn between a yes or a no. Rather, somehow it seems his whole identity is in flux, that he as a person has become undefined, unbounded. Like that same seed of hope over and over, a tiny seedling growing into an endless forest, so this simple binary question has somehow spawned innumerable forces pulling him in every direction. These forces are not pointing only towards all the different actions he might take: they are pointing to all the different people he might be. He’s so conflicted, utterly confused…

Until he suddenly notices that he actually isn’t. In fact, the answer is startlingly clear, perfectly so. And what's more, Crono realizes that for as long as he could remember, he had always felt this way: somehow, he just hadn't noticed it until this very moment. Crono opens his eyes, and looks up. His friends, standing nearby, are all watching him. After so much thought, Crono feels fresh and confident. He turns toward the small, strange creature who had asked him if he believed in fate. He opens his mouth to speak.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

That Weird Little Hill Outside the Engineering Center

Class ends and everyone starts putting away their stuff. I sit there for a few moments even though my stuff is already put away, because I don’t want to be the first person to get up and leave the room because I feel guilty because I hadn’t been paying any attention. I would say that it’s funny, that I’m distracted by my phone even though the things in class are more interesting, at this point, than the things on my phone. Except it’s not that funny, but more importantly it’s kind of a fake comparison. It would be a fun little morality play to tell myself, to notice again how this desire for distraction becomes so extreme, so desperate, that it somehow becomes far more boring, at least in a sense, than it would be to just do the right thing. But that wouldn’t really be true, because the simpler explanation is just that I’m a little behind in class and I can’t really understand today’s lecture so of course I’m distracted.

Finally I pick up my backpack and put on my jacket and head through the door at the back of the classroom. I’m walking through the hallways and now looking again at my phone. It’s interesting, in fairness, I mean better-than-usual but also actually interesting. You see Blue Origin is a space company that wants to make reusable rockets – you’re thinking of SpaceX but they’re different, SpaceX makes the Falcon 9 and flies missions to orbit with real payloads but Blue Origin hasn’t done any of that yet, they’re still all research-and-development. They can afford to play the long game because the company is owned by Jeff Bezos, same guy who owns Amazon, and while they might both look like rich tech billionaires to the rest of us, Bezos has something like ten or twenty times more money than Elon, so he can fund all these rocket engines and test vehicles and all that just straight out-of-pocket, and doesn’t have to worry about closing the business case until later. Anyways Blue Origin has just announced some more details for their big new rocket, meaning like I mentioned the one that’s intended to start doing real business. It’s huge, of course, which is awesome, like half or two-thirds the size of a Saturn V, but everything is huge these days, it’s exciting. I can’t imagine how awful it must have been to be an aerospace engineer twenty or thirty years ago, when everything was always the same and if you were lucky you got to help shuffle shuttles around while you waited for the internet to get invented. But what’s really interesting about this new rocket, New Glenn they want to call it, isn’t the size, it’s the design. And what’s more interesting than the design is the approach. SpaceX like I said is already flying real missions, they made the rocket first – which for the record was a great rocket even before it could come back and land on a boat – and then they added everything else later, the reentry burns, the grid fins, the landing legs, very iterative, test test test. But perhaps as a side effect there was just a little a bit of opportunity cost there, because looking at New Glenn you can just tell, it just feels more polished, more cohesive, so obviously designed from the ground-up to be A Reusable Rocket, the way they have that aerodynamic shield around the engine and the landing legs that tuck so nicely into the body of the rocket and like wings, like huge fricking wings actually, with which apparently they’re going to glide for a really long time through the upper atmosphere, bleed off velocity, avoid a hot reentry that might damage the engines, plus no need for a boostback or reentry burn so that’s a massive amount of fuel saved which equals a whole lot more delta-V for the payload. Clever stuff, certainly, really interesting, but maybe it’s not all quite so great as it looks on paper. The Falcon 9 is already flying right now, for starters, and that means they’ve got all kinds of experience and they’ve had opportunities to work out all the bugs and they’ve been able to change the design of their rocket as they fly it, for instance to make it easier to manufacture or help it have a faster turn-around time for reusability, and you don’t get those advantages with the more secretive pre-planned Blue Origin approach.

I’ve just stepped outside the engineering center now and I switch to wondering whether I should walk home or try waiting for the bus. I think about this almost every time I leave the engineering center despite the fact that I almost invariably walk home instead of waiting for the bus. It’s odd because when I’m leaving my house and going to the engineering center, I take the bus pretty often, maybe even a little more than half of times. Why do my preferences change just because I’m coming versus going? Probably the main reason is that I’m rushing when I head to class but I’m not really in any rush when I’m going back the other way, and if you happen to catch it then the bus is obviously much faster than walking. Another thing that’s definitely true is that the bus to school always has room, wheras the bus from school is sometimes full with all the students who just got out of class, and of course the times when it’s mostly likely to be full are exactly the times when you most want to take the bus because so does everyone else, for instance when it’s snowy or icy or just cold and windy, and then you’ve waited all that time in the cold for nothing and you still have to walk. There are other factors, too, like when I leave from my apartment I can look down the road for a long way and see if the bus is coming, and pretty often if I see it’s coming I can run to make it to the stop in time, so there’s a bit of flexibility there, in a sense, I can also see how many people are at the stop and judge whether the bus just passed by and picked everyone else. It’s kind of hard to explain but having that information about where the bus is allows me to either wait for it or not wait for it in a more intelligent way than I can at school, where it’s more random and so on average I’ll end up waiting more. And then there’s other things, like there’s a big hill on the way to school and maybe secretly I hate going up the hill and that’s why I take the bus on the way there even though as far as I can tell I’m pretty sure I don’t mind going up the hill. Or maybe psychologically it’s easier to walk home and feels like a shorter trip but walking to school makes it a slog. But no matter how many good reasons I think of, the asymmetry still bothers me.

While I’m thinking about the bus I’m still looking at my phone; I never like having stuff running down the battery in the background so I tap to close the couple of tabs I was maybe gonna read and then double-click the home button and start swiping apps to close them. I click the screen off and put it in my pocket and then I pull my hood on and kind of jerk my shoulders to heft up my backpack so it’s more comfortable, and then I look up and up standing on the top of that one little grassy hill is just this girl.

It’s also night. The sky is dark deep-blue. The buildings around the college look very different at night, more like a city, a warm glow shining out through the little windows on the dormitories, streetlamps here and there full of sodium light. In front of the engineering center there’s this wacky little hill, maybe four feet high, very round, very green, all by itself, surrounded by like at least twenty feet of concrete on all sides. In the daytime when everyone’s going to class there are always tons of people walking around on the concrete, walking and parking their bikes and standing around talking to one another. But now it’s night and nobody’s here, there’s just one or two people walking across the campus, listening to music with their headphones in, and then this girl standing on top of the hill, looking kinda towards where the mountains would be, although for the most part you can’t see them behind the dormitory.

She’s a pure silhouette in the dark, but nevertheless I recognize the girl as Lakshmi, who I know from a group project we both worked on when we were in Fluid Dynamics last semester. She is the only person I know in the aerospace program who is Indian but not actually an international student, although she’s visited the country often enough to have fond childhood memories of Diwali in Udaipur where her aunt and uncle and grandparents live. I know this because it was around Halloween last semester when we were working on the group project, which was a bunch of Matlab code to simulate the motions of some weather balloons released inside a thunderstorm, and I mentioned how it’s funny that holidays from around the world can end up having some of the same qualities, and I wondered if maybe it had to do with being in the same part of the year, or possibly it’s coincidence because maybe there aren’t enough ways for holidays to be different from each other so they always end up sharing a couple of things. We talked about honeyed sweets from street vendors and firecracker celebrations in the little alleyways, and warm little candle flames glowing everywhere at night, like in a church.

I walk up on top of the hill next to her, and say “hi”. She says “hi” back. The grass is pretty soft; I can’t remember if I have actually walked on this hill before but I have definitely never stood on top of it. The whole engineering-center plaza looks the tiniest bit strange now, even though I’m only four feet higher up than normal.

Lakshmi is wearing a medium-length black dress; she must have been at that Lockheed Martin event earlier. I think, that must be cold, but then I realize that actually the night isn’t very cold. I take off my hood. There’s just the tiniest breeze that I can feel, and now in the corner of my eye I can see some trees, and their branches sway a little in the air, making a nice sound.

“Isn’t it funny,” she says, “how when you’re looking straight ahead, almost half of what you can see is sky, but nothing ever really happens in the sky? It’s very beautiful sometimes, but it’s almost never relevant to anything humans do. Half the world is just sky, and the other half is just the ground, and everything we think is interesting lives in a tiny little strip near the horizon.”

“That is funny,” I say.

“Even when it rains,” Lakshmi continues, “Even when it rains, you don’t look up to see that it’s raining. You can already tell by looking at the ground. So, there’s really no reason at all.”

I look up at the sky. The brighter stars are out by now. Venus is the brightest, low over the mountains, following the sun. Its gold light feels even more beautiful contrasted against the rich, deep blue of the western sky. Jupiter is higher up, its bright beige-pink light adding an extra jewel to the colorful reds and blues of the winter stars near Orion. There are no clouds. It’s dark and very quiet, except for the sway of the trees and the sound of the cars, far away.

“Isn’t it funny that there are all these dorms,” I start, “and there are all these undergraduate students who live in the dorms, and they have meal plans and eat at the cafeterias, and they go to class each day and in the evenings they go to all these campus events or go to parties, or maybe just sit in the common room with their friends and play videogames? And I’ve never once been inside any of these dorms, or eaten in any of the cafeterias, or any of that. It’s a whole different college.”

“Yes,” she responded, “They have all these Centers. Like the athletic center, the theater center, the music conservatory. Or that thing with the big flat roof they’re building over there.”

Lakshmi is pointing north, towards the stadium and, beyond it, downtown Boulder. I am intimately familiar with the dark outline of the gigantic building she is referring to, since I walk by it every day on the way home from class, but I have no idea what it contains.

“Sometimes I think I should go to some of those things, you know, all the college things. Just out of curiosity.” I say to her. “...But then I just start thinking about everything else I want to do, in the same way, just to see what’s there. Like, have you ever been for a hike in the flatirons?”

I point to some of the mountains peeking out from behind the left side of the dormitory. Even though it’s night, they are illuminated by a faint grey light. I can’t see the moon in the sky, but it must be up, probably hidden behind the engineering center.

“Do you mean those ones in particular, or..?”

“No, just in general.”

“Then yes, I’ve been.”

“When I was at Colorado College, which is in the Springs, it was a lot like here with a nice view of the mountains,” I say. “So every day, walking to class or eating dinner at one of the on-campus places, I would always be looking at these mountains. By senior year I’ve been looking at this beautiful vista for four years, and I know that Pikes Peak is one of the easiest mountains to climb – people literally drive to the top, there’s this dumb train and everything. So I’m like, obviously I have to climb it, how crazy would it be to look at something for four years and never be able to go there and look back? So I set off one weekend, and for the next two days everything I see is just completely unbelievable. Like, first off, once you climb the first little hill out of the town, there’s this massive valley before you get to the mountain. You spend the entire first day just walking through the forest – it’s high altitude but it’s not really part of the mountain, it’s not sloping upwards. It’s just, like, secret land. And I had had no idea it even existed, and there’s nothing there but forest, like it had been folded up. When I had always figured the mountain was more or less right there after the foothills. Then on the second day you actually climb the mountain, and in addition to being huge of course, it’s just so incredibly, like... three-dimensional.”

Lakshmi laughs. “Yes! Yes, I know what you mean,” she says. “Like that statue in Chicago.”

“Yeah! I just couldn’t believe my eyes, this thing I had stared at every day for four years had suddenly become totally curved and warped out, so in a way I had a better understanding of the real shape, of course, but it was also so gigantic, and so different, that I felt disoriented. And the view kept changing, of course, so eventually it felt like they were all, not wrong, but like... equidistant.”

“It’s so funny,” she said.

“Yeah.”

“You know what else is funny,” said Lakshmi, “There are so many things that we can’t think about. Or can-but-don’t, or maybe we can think about them, but not in a way that we can notice or not in a way that feels like thinking. And I don’t mean the sky, or the mountains, or anything even close to those things, because clearly we can think about those things, and in fact they are perfectly ordinary thoughts.”

As she said this, Lakshmi ran a hand through her hair, which was dark and straight and long, and then started doing some intricate thing, gathering up her hair into sections and passing them one over another. I watched her as she did this, and she continued with what she was saying:

“But it’s like those things. It’s like the sky and the horizon, and everything we can think about is on the horizon. Sometimes the horizon is really narrow, even more than usual, like... those glasses that are worn by the Inuit, in the snow. And then you can forget about almost everything else in the world, and all your thoughts are these loud, discrete things, like digital signals. Other times it’s better and the horizon opens up, and you can see much more and it feels like you can have all kinds of thoughts, all together. But it’s never, for instance... I mean, the whole sky is there the entire time. But even though it’s always there, it’s never the whole sky. There are so many parts of my life that I can’t say –”

“Yeah, and it’s not like they’re inaccessible,” I offer, “or like they’re out of reach...”

“No, certainly. It’s like – the whole concept is that we’re not wearing the snow-glasses, the whole sky is always there, it’s a part of me, but it’s as if it’s a part of me that isn’t part of me. Or something. It’s very strange. It makes me sad, when I think about it.”

Lakshmi summons a hair-tie and tilts her head sideways for a moment as she fixes the bun in place. I look down at the ground, and notice that I can see our two shadows stretched onto the plaza below the hill. I wheel around to catch sight of a nearly-full moon, which has just emerged from behind the engineering center. I watch the moon for a while, and I must not have heard the click of her shoes against the concrete, because when I turn back around she’s gone.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Saccade I.

The eyes saccade.

Point to point, word to word -- even when you think you’re holding still.

Overlapping images slapped down like dealing cards, too fast to count. A Brownian panic: keep truly still too long, you’re going blind. First you’ll feel the tension: an urge to blink, refocus, reconverge. Any excuse to dart away. Hold still further. Now you watch as edges gray, textures tessellate, outlines blur. The world wasn’t meant to be looked at in this way.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Opportunity Costs

Here are some stories that I have sometimes wanted to write, but haven’t. They are arranged so as to make a progression on some kind of weird story axis that I apparently have, which starts off in nerdy-space-fan-land, wades through a bunch of weird triumphalist Bioshocky philosophy stuff, and ends in a land of morbid brooding Bioshocky philosophy stuff. If many of these sound like stupid ideas and/or sound more like vague, slightly evocative one-paragraph concepts rather than anything that could become an actual, satisfying, fleshed out and well-written story... Well, obviously that is probably part of the reason why none of these ideas have ever completely made it off the runway.

Untitled mars poems: A poem, or pair of poems, written from the perspectives of Mars and Earth. Each views the other’s distant colored light, and constructs a vision of the other that reflects the fascinations of the beholder as much as the realities of the distant beholden.

A Reliquary of The Planets: Related to the above, a series of posts laying out a system of aesthetics and connotations for each planet of the Solar System. These aesthetics sometimes differ markedly from the conventional interpretations that occasionally insist on absurd notions. (Such as that distant, desolate mars is a hot-tempered brute!) Some planets have two separate aspects, with the first being based on the planet’s appearance in the night sky and the second being based more on the planet’s actual surface conditions and general role in the Solar System.

Stardust: An alternate history where celestial mechanics was known since antiquity and a modern cosmological understanding of the universe was first articulated by Arab scholars in the middle ages. Several years ago, Galileo’s discovery of the cosmos’s expansion has inspiring hope throughout Christandom that further inspection of the heavens might finally resolve longstanding, fundamental theological questions. Now, Johannes Kepler studies alongside other natural philosophers in the massive project to discern the truths which will resolve these competing theologies. In his interactions with the other astronomers, he comes to question the purpose and value of scientific investigation, and ponders the sources of his own motivation for the project. The story ends on a moment of ambiguous revelation; far from discriminating among the competing theologies, a sudden scientific insight only serves to multiply the possibilities.

Aria: A shipwrecked navigator encounters an old woman claiming to represent the last inhabitant of a fallen civilization. Each day, she tells him more about the great metropolis whose ruins now litter the desert, and the fantastical inhabitants whose eyes always focused on the far horizons of the desert and distant skies, a race of men and women for whom the past and future were as real and powerful as the present moment. Meanwhile, the navigator’s dreams are consumed by rich visions equally incredible: sensations of fog and fire, tantalizing images of bodies dancing in the jungle, and an access to reality more vivid and profound than even what Aria’s stories describe.

Untitled Only Revolutions posts: Like the Only Revolutions posts that I already wrote, but longer, more detailed, and more personal. Rather than being a close analysis of the whole story (which simply be too big, too hard, and would take too long to write), this series of posts would be one part exploration of my personal relationship with the themes and story of the book, and one part long detailed asides attempting to mythologize certain aspects of basic calculus and also talk occasionally about subatomic physics and how Only Revolutions represents and engages with those beautiful and mysterious subjects.

The Exegesis of Mass Effect 3: Beginning with selective coverage of certain critical moments in the second game, we then trace those primordial ideas as they develop into the powerful thematic threads that web through Mass Effect 3. A succession of devastating thematic “crises” throw the game’s fundamental dualities into ever-sharper relief, yet simultaneously lay a foundation of remarkable cohesion and complexity upon which the game’s remarkable, transformational conclusion will be balanced. A “Mass Effect 3 Book” to complement my Braid and Bioshock efforts.

Untitled Greek-god story : All is quiet in the pre-dawn hours of June 16, 1945. The three goddesses Artemis, Aphrodite, and Athena engage in a cryptic but wide-ranging dialogue as they wait out their last night in the world.

Untitled future-history novel: A sprawling, lively, and inventive future-history in the style of “Stand on Zanzibar” and “The First and Last Men”. With nations around the globe facing dwindling resources and changing climates, human societies respond with panic, denial, and wild gambles. Many places once united under the banner of “Western Civilization” have abandoned the enlightenment project of liberal democracy: a movement is growing in the western United States seeks to create a technocratic corporatist state, while parts of Europe seek a return to reactionary values and monarchic authority. Nations like Canada, Japan, and Saudi Arabia attempt to retreat into their own private utopias, while others like China and the USA direct their resources towards ambitious, long-shot save-the-world master plans (the intention behind which might actually be nothing more than diversionary entertainment for the national populace). Most dangerously of all, the possibility for a massive and devastating war is brewing in south and southeast Asia. (This general geopolitical collage is, like in “Stand on Zanzibar”, illustrated by the interweaving stories of several characters and complemented by short vignettes of our surreal future.) At the center of it all is Bhutan: a remote mountain kingdom still lagging far behind in the race to modernity, squeezed on all sides by the ambitions of its neighbors, which can escape catastrophe only by finding its way past the Scylla and Charybdis of a dying world.

Defibrillation: Shameless, pathetic, ridiculous, System Shock / Bioshock / Amnesia / SOMA mashup fan-fiction, with inspiration taken from the manner of all of those games (obviously) as well as from “2001: A Space Odyssey”. After the events of SOMA, the Ark’s sensors pick up the first unambiguous signal in over a decade of lonely monitoring. The starship Von Braun, the first spacecraft fitted with interstellar drive technology, has returned from its maiden voyage to Tau Ceti IV. Simon and Catherine instantiate themselves onboard the Von Braun, only to discover that the crew have been murdered and the ship commandeered by an alien biomass that refers to itself as “The Many”. The Many has come to the Solar System seeking to wipe out any remaining trace of SHODAN, a vengeful artificial intelligence who opposes The Many’s vision of all life melting into the unconscious euphoria of the flesh. Simon and Catherine hope that if they can kill The Many and take back control of the ship, its design as an independent, self-sustaining arcology could act as a seed for the revival of human civilization. And of course, SHODAN has her own plans in mind... The goal is to get into an “Amnesia: A Machine for Pigs”-type attitude and create a kind of horror take on “The First and Last Men”, portraying humanity’s myriad attempts at civilization and utopia as doomed and degenerate actions that can only ever at most postpone or deny, and never actually successfully answer, the fundamental anxiety and horror of existence. The protagonists reject the potential futures offered by SHODAN and The Many, but (as in SOMA) the “humanity” that Simon and Catherine purport to defend is undermined by a number of unnerving Bioshock-style twists, until they are left regarding it as something ambiguous at best, repulsive at worst.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Six

[For other chapters, click here.] I slept through most of that day, waking only in late afternoon. I dressed and left the quarters Aria had given me for a bedroom the night before, then began to wander the rest of this empty building adjacent to the dome and tower. There were perhaps thirty rooms of varying sizes. No one besides Aria seemed to live here, and Aria only barely. Even most areas possessed only a few decayed fragments of furniture. If Aria had any supplies or personal possessions, she kept them somewhere else. Although I did not find her anywhere, she had left me a large, simple meal of bread and boiled vegetables which I chewed down readily. By the time I had finished eating, I was beginning to wonder if Aria had not left the ruins entirely. I did not find her in the temple, but was heartened to spot her approaching as soon as I stepped outside the thick wall of the dome.

“Good, you are awake,” she commented as soon as she was close enough to speak quietly. “Did you see the food I left you?”

“Yes, thank you for it. Do you grow it yourself, somewhere nearby? It’s so empty here.” I sought to deduce whether she really did live in the ruins, or was only passing through.

She headed into the atrium, and I followed. “The creek nearby runs during part of the year; it dried up just a few weeks ago. Water can be stored to last through the dry months.” Then, “Would you like to begin the story of this place?”

I answered that I would.

“Good. We can walk,” said Aria, gesturing to the dome’s wide circumference. and then she began.

“Many ages ago, the forerunners of the Aevite peoples lived on an island called Anakena, similar in many ways to this one. These forerunners in turn descended from still more distant ancestors: an ancient and powerful island culture, unrivalled experts in navigation, fishing, and shipbuilding. And yet the people of Anakena were isolated from the beginning: they never intended to settle that place, but were blown off their original course by a fierce storm--”

“Stop! Stop,” I burst out. “...Why are you doing this?”

“I am sorry. I know why it is difficult for you to listen to this,” said Aria, who stopped walking for a moment and turned towards me. “I know well the pain of too-vivid memories. Many here have been haunted by catastrophe at sea, not just you. Indeed, none have arrived at this island by their own choice. But please, do listen. I tell you this story not to taunt or torture you, but to help you. To teach you. You must trust me.”

I nodded, trying to hide the shuddering of my fearful breath. She continued.

The Story of Anakena

Aria described how the unwitting settlers drifted for weeks after being blown hundreds of miles southeast of their original course. Later, long after they had discovered Anakena and established themselves, occasional attempts were made to reconnect with the outside world. The expeditions may have been successful, but they never returned. Eventually, people stopped trying.

Meanwhile, the first settlement on the island grew into a prosperous town. The island was arid but fertile, with good soil and plentiful resources. Within a generation, Anakena was dotted with small farming settlements and fishing outposts. In another, some of those tiny settlements would become large and sophisticated urban areas. The island came to be ruled by five proud houses: the Matua, the Manutara, the Roa Koihu, the Ovare, and the Ara Rakei. The most powerful of these was the Ara Rakei, whose matriarchs ruled from the populous and influential city of Avarepua. The houses were peaceful, the people flourished, and in over the years they decorated their shores with the stone-carved images of many wise leaders.

However, in their industry, the people of Anakena were working many subtle changes on the land. Decades of farming slowly began to sap the soil of its productivity. When this happened, the land was set to lay fallow. Over time however, as farming became less productive, it became necessary to supplement the produce of active fields with extra meat from larger herds of grazing animals. But while they grazed the unused land, shepherds’ flocks would would destroy native plants down to the roots, leaving unprotected soil to dry out and blow away. Thus, as soil conditions further worsened resulting in lesser yields from both farm and flock, the population of Anakena began to rely ever slightly more heavily on fishing for sustenance. This was successful for a time --after all, the ocean is a boundless thing compared to the island--, and stability seemed possible. But stability only encouraged the enlargement of the cities, and a steady growth of the island’s population. Under this increased strain, even the lush reefs which had sustained Anakena’s early needs were also stressed too severely, and began to fail. Unfortunately, the five Houses were slow to recognize these kinds of problems and slower in comprehending their causes. Effects like these were miniscule at first, but numerous. As each worsened, the total effect was compounded --by the time all the island’s rulers fully comprehended this, Anakena was well on the path to suffering.

Before that, though, the young princess Shadiya of the Ara Rakei was the first to perceive the looming catastrophe. She was brilliant, and as the daughter of a House matriarch she was well-educated in both politics and theology, though she had fondness only for the latter. Although Shadiya was raised in the palace at Avepura, whenever she found reason to leave --which was often-- she always displayed an incredible aptitude for understanding the natural world. Alone, wandering the grassy hills of Anakena’s countryside, she felt a freedom and grace that would go unwitnessed even by close friends during her life at Avepura and in her eventual role of matriarch. In the fields and in the forests --which, though small, still existed in Ara Rakei lands when she was a child-- she would watch the business of insects, play at building bridges and stone dams across the many small creeks that ran amongst the foothills, and listen to the songs of birds, noticing their pattern and even their slight change from year to year. By the ocean she would watch the currents and the patterns of the weather while listening to waves crash against the rocks. Even though she visited the ocean only rarely and at uneven intervals, she became familiar with the tides and with the way that the beaches changed throughout the year, steepening during winter while battered strong waves, then relaxing again each summer. And when Shadiya returned to the palace from her every excursion she never failed to bring with her many flowers, bits of sea life, strangely-shaped rocks, and other curiosities, to be examined later. But the princess’s intense interest in the natural world was not something that she shared with others. As the world regarded her, Shadiya’s greatest and most distinctive aspects were her incredible foresight and strong powers of self-control. Even as a child playing with impulsive peers, her rare actions were carefully premeditated and precise. Throughout her childhood and into her adolescence she rigidly adhered to a cryptic, hidden system of moral strictures and personal ideals. The etiquette of palace life, even the friendly advice of friends and relatives became for her the elements of a larger good, a moral absolute which nobody else perceived but by which she might demonstrate her virtue through her dedication and obedience. In time, of course, she outgrew the childish particulars of her code. But while her imagined laws changed, Shadiya’s devotion to them remained strong. Even when after many years she rose to the position of martriarch, and no worldly authority remained to impose its will on her, Shadiya stayed her every course according to her unvarying internal moral compass. In this way she ruled decisively but with a cool head, leading Avepura and the Ara Rakei to an even greater position of prominence. For a time her future as matriarch looked very bright, but all the while the future of Anakena was eroding around her.

0 notes

Text

Five

[For other chapters, click here.] I dreamed, afterward. I was falling asleep just as the sun began to lighten the faint, icy wisps of cloud visible through the skylight above my bed. There is a moment, somewhere between the vacuum of darkness and the bright clarity of day, when the world’s fiery penumbra races across those high clouds. Each misty filament becomes an eruption of golden light, saturating the still-somber sky in those liminal minutes which anticipate the true dawn. I dreamt of a light still deeper, a warm and ruddy glow in the close darkness. The air was thick and heavy; I breathed it in and was filled. I could hear rumbling thunder in the distance.

0 notes

Text

Four

[For other chapters, click here.]

She was sitting cross-legged in the exact center of the atrium, illuminated by one of several beams of pale light that entered through thick glass skylights in the dome. She wore a thin grey robe, with a separate veiled headdress that kept her face in shadow. I took a few steps into the atrium, then stopped as the sound of each footfall echoed throughout the space. Aria did not look up. I then called out a greeting, but still she seemed not to notice. I resumed walking toward the center, noticing a peculiar excitation of the air as I did so. It was a high, ringing sound, growing steadily in volume as I approached the center of the atrium. By the time I was a few steps away from the focus of her note, the reverberation felt like was passing through my entire body, like I could feel the quickly alternating pressure of the air against my skin. Near her seated form, individual sparkling grains of sand were jittering across the stone floor, congregating in symmetrical patterns of resonance. Even dust suspended in her beam of moonlight responded to her hum, vibrating through nodes and antinodes of invisible energies.

She looked up at me then, and stared at me for a handful of seconds, dark eyes perfectly still, while the singing walls of the atrium wound down into silence.

“You are welcome here,” she told me. “I am Aria. I can give you food and water for as long as you need to stay. But if you stay, I ask that you listen to my story. And if you choose to listen, I ask that you agree to hear the entire sequence before you leave.”

I stood frozen, arrested by hearing my own language spoken perfectly by this unearthly being.

“Certainly,” was all I could manage to gasp out.

“Good. Let us go, then, and I will bring you water.”

Aria led me to a complex of rooms adjacent to the temple dome. She stopped in a small room with a low table and a fraying straw mat for sitting, and gestured for me to stay there while she brought water and a second mat. The table was a weathered wooden surface held up by four uneven stone blocks; otherwise the room was bare. In this and the other rooms we had passed through, I saw no candles or lanterns; the only illumination came from the skylights in the ceiling. A strange choice, I remember thinking, for someone awake during the deep hours of the night.

Aria returned with a large glass flask of water, and unrolled her mat to sit across from me as I eagerly drank. When I finally put down the flask, she was still for just a moment before raising her eyes to meet mine. Then she began to speak.

“I, Aria, am the ultimate singularity of that once noble and fascinating Aevite culture whose works long ago became the ruin you witness today. The Aevite were not destroyed by war, famine, or disease, like so many unfortunate peoples. Rather, we were the deliberate agents of our own demise. In the deepest of ways, the world had never truly been fit for us… when we comprehended that horror, we could not bear the thought of continuing. There was nowhere we could have hoped to belong.”

She continued, “As such, the memories within me are the only chronicle to be found of that culture: their triumphs and failings, their insights and their ignorance, the way they lived, and the things they valued. I ask that you stay and hear my story in order that I may impart to you something of the essence of the Aevite, and this their citadel.

“Theirs is a history to which I have devoted nearly the whole of my life to contemplating and understanding. I am the sole vessel in which my civilization resides. But, if you are willing to listen carefully and remember well --if that is the case, then perhaps the Aevite need not die with me.”

1 note

·

View note

Text

Three

[For other chapters, click here.]

Curiosity, allied with hunger and thirst, were now in competition with my shame. Eventually I stood, and started moving towards the light on the horizon. I thought I had abandoned the streambed to do this, but I crossed its desiccated bends several times as I walked south. The land between was equally sandy and bare, adorned only by the arid twigs of a few long-dead bushes.