Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

The Internet Fee: how we’re paying with our personal data

These days, it’s rare to click on a website without a message like this popping up:

Keen to continue scrolling, we quickly dismiss the message and carry on with our lives as if cookies aren’t even a thing. But actually this notice is not only required by law, but it’s also a vital reminder that our every move online is being tracked and recorded.

The boxes we tick and the messages we accept are actually agreements to the sharing and usage of our personal data. The Cookie Law is “a piece of privacy legislation that requires websites to get consent from visitors to store or retrieve any information on a computer, smartphone or tablet... It was designed to protect online privacy, by making consumers aware of how information about them is collected and used online, and give them a choice to allow it or not.” (1)��

But in reality, no-one bothers to sit down with a brew and read these privacy policies, so websites and browsers can subtly use the information we provide in order to personalise our online experiences. It’s interesting to uncover just how much the internet seems to be watching what we do online...

Example 1: Facebook ads

Targeted ads on Facebook allow companies to advertise their product or service to an audience of people most likely to invest in it. Using the demographic information users voluntarily share with Facebook, these ads specifically focus on people that match the brand’s target audience. So this morning, the top ad on my Facebook page was:

So it’s clear Facebook somehow knows I’m a student... but how? I don’t remember entering the fact that I study at university or will be looking for graduate jobs anywhere on my profile...

Example 2: Amazon

Usually the place I go to buy random stuff I can’t find anywhere else; my Amazon account has witnessed some strange purchases. By recording everything I search and buy, it offers suggested products that “I might like”. However, personally this feature is not that useful to me, as I tend not to buy multiple products in repeat from Amazon - it only really serves to remind you of the last thing you bought (which in my case was a plug).

Example 3: Spotify

Actually useful this time, Spotify listens to every song you play, and uses this data to recommend new music it predicts you will like. Through facilities like Your Daily Mix, Discover Weekly, Release Radar, Your Time Capsule, Your Top Songs 2018, the app can broaden your horizons by exposing you to new music, or reminding you of the golden oldies you used to love. This is definitely one case where the use of personal data and activity is beneficial to users.

Example 4: The Health App

I have no recollection of switching on / activating / signing up to this app, yet when I opened it for the first time this morning I found records of exactly how far I’ve walked, how many steps I’ve taken, and how many flights I have climbed, on every single day since I got the phone. So if Apple knows this stuff before I do, who else has had access to private information, such as where and when I’ve been walking?

Example 5: Basically, all websites

Virtually every website tracks your digital footsteps and uses your personal data in some way. For example, this radio show’s website needs access to your geographical location to “determine you are within our broadcast area”, and uses cookies to “provide you with the best user experience and to deliver you with advertising messages that are relevant to you”.

So cookies aren’t necessarily bad things, as they help your experience online run smoothly and efficiently, and supply relevant information to you based on previous searches and actions on the internet. However, the internet seems to be becoming increasingly commercialised, with every click becoming a valuable piece of information for advertisers. Everything you give away about your life through the internet can be used by online marketing companies to target you.

It’s worth being aware of the implications of sharing personal data: instead of predicting what we might do next, these processes can lead to influencing future behaviours. This is described as Economies of Action:

Economies of action = when systems are designed to intervene in the state of play and actually modify behaviour, shaping it towards desired commercial / political outcomes.

What might seem like a quick, free Google Search is actually being paid for with your private, personal data, which is gold-dust to online companies and advertisers on the internet.

Sources:

(1) https://www.cookielaw.org/the-cookie-law/

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

The life of a Love Island lady

From a novelty ITV2 show to a nationwide obsession, Love Island has undoubtedly become essential summer viewing for the majority of young people. As a result, it’s now the norm for Islanders to go on to become influencers, presenters and “celebrities”, targeting an audience of young adults – and lots of this is achieved through the means of social networks, especially Instagram. But a quick scroll through the accounts of a handful of female ex-Islanders highlights a concerning issue: trolling. Negative, abusive, insulting comments sit just below most posts, critiquing not only the photo itself, but the person behind it.

Known for being confident, passionate and argumentative both on and off the island, Olivia Atwood now has over 1.6 million followers, as well as multiple follow-on reality TV features since 2017. And yes, a large proportion of her posts on Instagram could be considered provocative or seductive. However, the post above is just one example from hundreds of pics which are met with negative comments and opinions based on her physical appearance. From her make-up to her figure, people were quick to publish their thoughts on how she looks (and therefore how she “should” look).

As an influencer, with plenty of money and a pretty glamourous lifestyle, it’s not surprising that Liv posts these kinds of images – but why do some people feel it is OK to be so vocal with their personal judgements in the comments?

One explanation is that it’s down to an underlying jealousy: perhaps people feel it’s unfair that she suddenly landed in fame and fortune by sitting around in the sun on a reality show, allowing her to live this luxurious lifestyle and look so unattainably good. Alternatively, social media provides anonymity and a sense of “untouchable”-ness that may make some users more comfortable to criticize the appearance of Insta celebrities – a behaviour they would be far less likely to replicate in a face-to-face interaction.

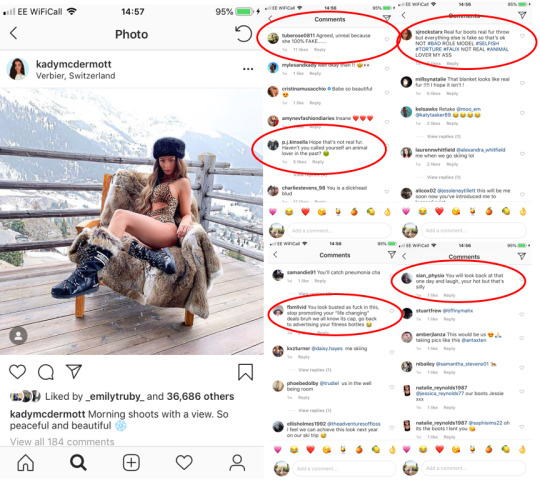

Launched into fame in 2016, Kady McDermott has since become “Brand Owner|Model|Make-up Artist|CEO of @bykady_ and @bodygoalsbykady”, according to her Insta bio. And similarly to Liv, her account displays her lavish, desirable lifestyle – yet most of her posts are also met with some negative feedback.

The comments on this post are particularly interesting as they focus on criticising her morals and credibility as a person, rather than her appearance, unlike the previous example. Comments poured in attacking her association with fur, accusing her of supporting the fur trade and questioning her character (as she has previously spoken against the use of fur).

Moral values are a significant factor in why some users leave insulting comments online. When people believe that moral justice has been broken, they automatically feel a sense of entitlement to be offended, therefore can justify their own attack on the person behind the post. In this case, the emotional arguments behind wearing fur could provoke some users to react aggressively in the comments, as their expectations of Kady’s morality as a human have not been met.

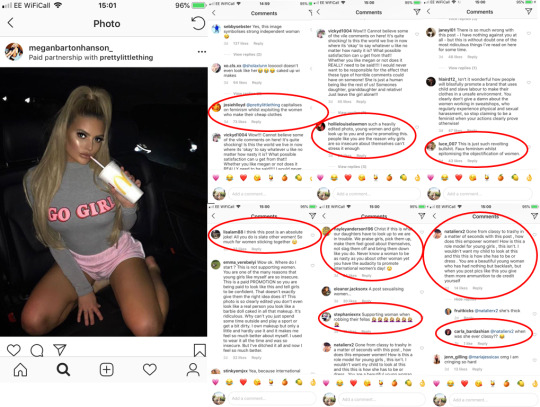

Similarly, Megan Barton Hanson from S4 received criticism for an International Women’s Day pic she posted recently, where people shredded into her morals and values, accusing her of disrespecting women and being a poor role model for young girls.

While Megan’s Insta output is not the most appropriate content for some audience demographics, such as young teenage girls, commenting negatively on public posts can have harmful impacts for the person who posted it, in terms of mental health. This behaviour again can be explained by the importance of moral expectations: these commenters perhaps feel it is a betrayal of the trust of Megan’s followers for her to post such suggestive, sexualised images like the one above, and associate it with a day dedicated to feminine power and independence.

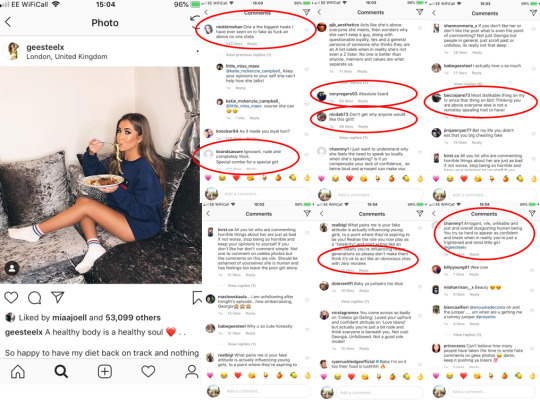

A final example of the millions of female influencers’ posts which receive hate from the public is that of Georgia Steel. The pic above received insulting comments aimed at Georgia’s personality, rather than her appearance or values. It appears that Insta has become an place for followers to share their up-to-date opinions of Georgia’s character, based on current TV shows such as Celebs Go Dating. Just a few short years ago, there was no such outlet for viewers to publicly announce their thoughts about celebrities to the world. Since the mass uptake of social media, anyone can write a permanent, globally visible judgement and directly address the person they are insulting, like never before.

Another possible explanation is that these commenters feel they possess more epistemic knowledge than the influencers: they deem behaviour such as Georgia’s to be inappropriate for the social circle it is visible to, and perhaps see it as their responsibility to inform the influencer, and everyone else, of this.

The content published by Olivia, Kady, Megan and Georgia on their Instagram accounts is (of course!) not going to be to everyone’s taste. They target an audience of young, predominantly female followers, and use Instagram as a tool for profit, through paid advertisement and product endorsement. However, ultimately their own accounts should allow personal expression and free speech. While you could argue that the comments themselves represent freedom of speech and opinion, they often provoke negativity around self-image and would not be said off social media. In cases like these, the screen acts as a barrier between saying insulting, offensive things, and facing any consequence or punishment from it: this can give some users the confidence to be provocative, personal, and pretty savage with their feedback.

The persistent nature of social media comments means that there can be ramifications from posting harmful ones further down the line. Social networking platforms themselves are also taking more responsibility over the issue of trolling, and it’s possible that we’ll see more serious consequences for it in the near future. For now though, it’s still concerning to see the number of unpleasant messages and comments left under the posts of social media influencers like the Love Island graduates studied above.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Put your pancakes away please – my Instagram’s not hungry

Despite being possibly my favourite Tuesday of the year (it’s a whole day dedicated to a hot, sweet food... obviously?), Pancake Day inevitably brings a tidal wave of social media spam along with it. From pancakes that deserve a Michelin Star to those that deserve a place in the bin, Insta feeds and Snapchat stories suddenly fill to the brim with pancake pics – and, to be honest, it’s a little sickly.

In fact, the whole idea of snapping and sharing photos of food is starting to get out of hand. What once was a novelty way of showing your friends what you were getting up to, has now become a laborious process: waiting for food, receiving it, getting out your phone, arranging a good set-up, taking the pic, deleting it because it was rubbish and someone’s hand was in the background, retaking it, choosing a filter, thinking of a caption, posting it, and... after all that, the food’s gone cold. So why are we bothering?

Perhaps it’s all part of our desire to portray a positive image of ourselves on social media. Check out the following Insta post:

By posting this artistic, aesthetic image of some blueberry overnight oats, this Insta user is immediately crafting their online identity as someone who: a) cares about eating healthily, b) takes the time to present their food beautifully, and c) has their life in order enough to actually make overnight oats.

Alternatively, the following post creates a different online identity for the user:

This post represents the user as someone who loves eating with their friends, therefore their followers may view this person as a sociable, outgoing, adventurous person (who enjoys eating burgers in their spare time).

Finally, this post creates a different online identity yet again:

The luxurious-looking food, accompanied by the “candid” woman drinking wine, and #datenight in the caption, all suggest that the person behind the post is displaying their relationship (and classy dinner choices) to all their Instagram followers.

Posting pics before eating has become kind of a pre-dinner ritual for young people. It’s not even really an art: Insta filters take care of the lighting, and you can crop and zoom to your heart’s content on Snapchat. But that doesn’t stop some users turning into professional photographers in the middle of Nando’s, arranging their side dishes around their bottomless Coke, making sure the little flag in their chicken is facing the camera so that all their followers can see they’re strong enough to handle Hot.

However, food is a universal language: we all eat, and most people enjoy appreciating good food, so food photography is popular on the internet globally. Seeing particular dishes or items can stimulate memories from your past or inspire you to try new things in the kitchen. Furthermore, food is often linked to a certain moment or emotion; through posting food pics on social media, users can create a kind of food diary, linking specific memories to what they have eaten over the years.

So posting food pics on social media can be a positive way of promoting an image and identity online. Food can be very personal, so sharing what you eat with your followers can strengthen your relationship with them and shape the impression you give out online. However, the recent boom of the food-pic-trend has led to Instagram feeds being stuffed with so many “average” food posts that other photos (for example fashion, travel, and photos of the people you actually know) can be lost among them.

There is also the issue of mental health: using social media as a platform to promote certain foods or idealize some diets can be damaging for more vulnerable users, as some people may view these kinds of posts and think “I should be eating that”. A recent study suggested a link between scrolling through endless pictures of “healthy foods” and the development of eating disorders. The publication concluded that high Instagram usage is associated with a greater tendency towards orthorexia nervosa (ON), and interestingly, no other social media platform has the same effect. Read the full article here: https://www.dailymail.co.uk/health/article-4522730/Why-Instagram-posts-eating-disorder.html

Of course, encouraging healthy eating and an active lifestyle is a positive thing. Using Instagram to share a weight loss journey, find like-minded fitness fanatics or trade nutritious recipes can be useful for many people. However, it can also damage our self confidence, or more seriously, become fuel for a mental illness. The UCL researchers who conducted the study suggested 3 reasons for the link between Instagram and the eating disorder:

1. Instagram is all about taking the perfect shot of your protein pancakes, so you get maximum likes. Therefore, it establishes links between diet and popularity, food and image.

2. All the posts you see are from people you follow (or similar, on the explore page). Following loads of the #fitfam crew or food bloggers exposes you to extreme health messages, allowing for normalisation of behaviours which people may feel pressured to conform to.

3. Social media influencers are seen as an authority to look up to. Their posts reach millions of people looking for answers and advice, turning to popular 'celebrity'-like figures rather than experts.

Perhaps we should consider the impact food pics might be having on other social media users before posting. Does Instagram really need another pancake pic?

Images:

https://www.instagram.com/p/Buoj2u5A1b1/

https://www.instagram.com/p/Bunxq8nFfvR/

https://www.instagram.com/p/BklCeY1F7ea/

https://www.instagram.com/p/Bqz0Sb2Bpl5/

https://www.instagram.com/p/BupXeITAOem/

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Social media: a political powerhouse

From Brexit to Trump, these past few years have been... let’s say, turbulent. But in this new era where Presidents are tweeting and Prime Ministers are becoming memes on a daily basis, it’s actually surprising to consider just how significant social media has become in the 21st century: it has a huge role in the relationship between politics and wider society.

News around the clock – Many of us rely on Facebook and Twitter as our main sources of news, rather than traditional news websites, TV, radio or newspapers. What we read on social media, we often trust blindly. But everything that appears on your feed has been uniquely tailored for your eyes by algorithms and equations, so the news you’re exposed to is based on what you’ve previously liked, or what your friends follow: this risks narrowing your ability to consider different perspectives and ideas about the world.

Virality - Whether it’s Theresa May cutting shapes, or the latest outrageous tweet from Trump, some political activity can go viral in seconds, thanks to social networks. Rumours, conspiracies and fake news... all of the above spread like wildfire on social media, as these platforms facilitate the wide and efficient distribution of information, and utilise the existing social connections and relationships between users.

Direct interaction with politicians – Through output on social media, politicians’ can expand their voices and directly address the public, 24/7. Unlike speeches or interviews, social media posts are written and permanent, and invite responses from other users, allowing members of society to engage with politicians themselves. However, this has its pros and cons: while it’s useful for political campaigners to be able to get first-hand information and responses from people through social media comments, it also allows for trolling and abuse towards political figures.

Demographics, targeting and ads - Controversially, social media sites have been exposed for targeting political adverts at certain users, based on personal info, and data gathered seemingly without consent. This targeting has been accused of unfairly influencing election votes: look no further than Brexit, when the official Vote Leave campaign spent over £2.7m on targeting ads at specific groups of people on Facebook, which may have helped win the 2016 EU referendum. According to BBC News, carefully-designed ads focused on specific issues, such as immigration or animal rights, that were thought likely to “push the buttons” of certain people, based on their age, where they lived and other personal data taken from social media and other sources. The full article is here: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-politics-44966969

While social media definitely has had positive influences, for example improving the two-way relationship between members of society and people in power, there is no doubt it has raised important issues about democracy, news and political processes. In an increasingly digital world, there’s also the risk of disadvantaging those who are not active on social media, and losing the truth of the news behind a growing cloud of social media hype.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Now or Later: How asynchronous texting is messing with your mind

According to a recent survey, the average person spends more time on their phone or laptop than sleeping. Why, then, do some people take over an hour to reply to a simple snapchat? It’s one of the most annoying features of digital communication, yet we can all relate to that feeling of seeing a notification pop up and thinking “I can’t deal with that right now, I’ll leave it a bit.” Texting and messaging are asynchronous, i.e. delayed forms of interaction, with pauses between each person’s speech; this can have both positive and negative implications for those communicating through digital media.

Unlike actually talking (a synchronous real-time interaction), text-based computer mediated communication depends on both participants taking time to type out their message and hit Send once they’re sure it’s good to go. This can be useful, since it allows speakers to think about what they want to say and reword their messages, ensuring they’re appropriate for the audience.

However, a disadvantage of asynchronous texting is that any long pauses generally give off a rude vibe, making the other person question: “Why aren’t they replying to me? Are they mad? Have I done something? Do they still like me?” It’s kind of expected, especially among millennials and young adults, that messages will get a response pretty quick, so any significant time gap between them can make a person seem uncaring, moody or distracted. But the truth is, with the sheer volume of notifications we get on our phones daily, it can be common for messages and texts to go unseen. Similarly, when messages do pop up, we’re all living such busy lives that it’s easy to think “Ooh, I’ll look at that in a sec, I’ll just finish this”, and... half an hour later you’ve got side-tracked and suddenly remember you should probably open it and reply. Especially the more forgetful of us - it’s nothing personal, we were probably just watching Friends.

Digital communication can be described as “semi-synchronous”, as it allows users to choose their own level of participation. You even have the option not to respond at all - which can be advantageous in comparison to other forms of communication. For example, after answering the phone you’re pretty much committed to having a conversation with the caller, even if you don’t want to. Similarly, chatting in the street has social constraints; usually you have to stop and talk for a bit (while thinking of polite excuses to get away). However, ignoring texts and messages goes against all etiquette of digital communication, and people who do this are typically considered disrespectful and rude by others.

Asynchronous communication can result in disrupted turn adjacency (Herring 1999): since messages do not appear on the receiver’s screen until the writer hits Send, other messages can be sent in the meantime, separating related messages from each other. As a result, topics can be forgotten or replaced, affecting the efficiency of communication. Jones and Hafner discuss this as a limitation of chatting through technology: “Not only does typing, for most people, require more time than speaking, but there is an inevitable delay between the time a message is typed and the time it is received by one’s interlocutor. Even the most advanced chat system using the fastest data connection cannot imitate the synchronicity of face-to-face conversation.”

On the other hand, an advantage of text’s asynchronous nature is that messages are persistent and permanent. This means you can look back over previous messages and check what has been said at earlier points in the conversation, unlike speech.

So asynchronous communication does have benefits as well as limitations; it can be useful as well as inconvenient, usually depending on the kind of communication needed. Most of us have (shamefully) aired a few messages before, and we’ve all been left hanging... but perhaps we should consider the effects of delayed messaging next time we think about leaving a snap unopened for a bit.

Sources:

https://www.dailymail.co.uk/health/article-2989952/How-technology-taking-lives-spend-time-phones-laptops-SLEEPING.html

Jones, R. H. & Hafner, C. A. (2012). Understanding Digital Literacies: A Practical Introduction. London: Routledge.

Images:

https://www.pinterest.co.uk/pin/176203404152176039/

https://winkgo.com/15-perfect-responses-ignored-text-messages/

https://tenor.com/search/late-reply-gifs

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hooked on tech: are we all internet addicts?

I like to think I’m pretty independent and capable without technology - I say, sitting here with two screens open in front of me and a growing irritability about the library’s patchy WiFi. The fear that technology might be taking over our lives, terminator-style, has been popping up across the news in recent years, and yet pretty much everyone I know is still reaching for their phone first thing in the morning, and squinting at the little bright screen just before bed. No-one seems to be bothered. But is this dreaded “internet overdose” really something we should be worried about?

Beneath the pressing global issue of internet addiction, there lies as tiny chemical with huge importance: dopamine. Dopamine is one of the brain’s neurotransmitters, and studies have shown that dopamine relates to seeking rewards for particular actions.

Psychological researchers believe that “since dopamine contributes to feelings of pleasures and satisfaction as part of the reward system, the neurotransmitter also plays a part in addiction.” (1) It is thought that dopamine has a role in the learning process, since if certain actions are met with a pleasurable reward, those actions will be repeated, and will eventually become habitual.

Dopamine’s effect of releasing pleasurable sensations has led to it becoming... well, kind of a celebrity molecule. According to an article in The Guardian, the British clinical psychologist Vaughan Bell once described dopamine as “the Kim Kardashian of molecules.” (2) It’s so well-loved that people even get its chemical structure as a tattoo:

Dopamine’s responsibility for our body’s seeking and pleasure, wanting and liking, means it sneakily sets us up in a vicious cycle: The Dopamine Loop.

Social media encourages us to perform behaviours, actions, posts, and we seek some kind of reward from this. And, since the feeling of getting truckloads of likes on your latest Insta post is so amazing, we repeat over and over again, until the end of time. We compulsively check our feeds, desperate for another hit of that delicious dopamine that makes us feel so good.

And it’s true: internet addiction is a genuine, diagnosable illness, which can have a major impact over your life. Internet addiction can lead to similar problems to those of drug or alcohol addictions: personal, family, academic, occupational and financial aspects of life can all be destroyed by an addiction of this kind. People with this problem are likely to spend time in solitary isolation, disrupting human relationships and social skills. Some sufferers may create online personas where they can alter their identities and pretend to be someone else - those suffering from low self-esteem and negative self-perspective could be at increased risk of anxiety or depression. And there are tangible, visible withdrawal symptoms, too: anger, depression, sleep disturbance, irregular eating, mood swings, anxiety, fear, irritability, sadness, and upset stomach.

According to the charity Action on Addiction, 1 in 3 people are addicted to something (3). The seriousness of Internet Addiction is only just starting to be realized, but it’s a very real threat that will only get stronger the more we interact with technology on a daily basis. The NHS and Samaritans offer guidance and advice for people who think they are struggling with addictions of any kind.

As for me, I think I might start checking my phone’s Screen Time a little more regularly.

Sources:

(1) https://www.psychologytoday.com/gb/basics/dopamine

(2) https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2018/mar/04/has-dopamine-got-us-hooked-on-tech-facebook-apps-addiction

(3) https://www.nhs.uk/live-well/healthy-body/addiction-what-is-it/

Images:

http://parentingteenagersacademy.com/technology-addiction/

https://renudelaser.com.au/science-behind-tattoo-addiction-reality-fallacy/

https://digitash.com/technology/internet/how-dopamine-driven-feedback-loops-work/

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

For more information,

Hyperlinks. Trapdoors, embedded in the fabric of the internet, leading us deeper and deeper into the World Wide Web. Almost every website we visit has them, and yet we never stop to consider how significant they actually might be.

There are many reasons why the humble hyperlink is a fantastic tool for digital writers. By linking certain bits of text to other pieces, they organise the text in a non-sequential way, making it easier for us readers to quickly find the stuff we want to see. As Jones and Hafner describe, “the writer of a hypertext document creates a range of choices for the reader, who selects from them in order to create a pathway through the text”. Convenience, then, and ease, are massive benefits of using hyperlinks in online writing.

Hyperlinks can be internal, i.e. linking to another section of the same wider text, or external, i.e. taking you to a completely different text online. This means you can jump over irrelevant material on the internet and get fast-forwarded straight to what you want. Basically, an online ‘skip-the-queue’.

External links also enable writers to back up their own work by directing their readers to other webpages which support or prove it. Links take you to websites which go deeper into detail, or elaborate on the writer’s claims.

The great Wikipedia is the King of Internal Hyperlinks: pretty much every Wiki page is littered with blue underlines which escort you to various other Wiki entries. For example, by searching for William Shakespeare, I can follow a direct pathway of hyperlinks and end up on the page for The International Tennis Federation, in just a few clicks.

For external hyperlinks, most informative webpages will contain links to other websites, companies, shops, charities etc to offer further service or information: one example of this is The Telegraph’s Best Beach Guide:

Here external links allow readers to click straight onto different websites such as restaurants, hotels etc. near the beaches on the list, making the reader’s experience more efficient.

So, hyperlinks make online information clearly signposted, well organised, and easy to navigate. However, they can also allow users to carelessly slip into a mindset where we trust the pathway laid out before us by these links, and don’t think twice about what lies beyond the little blue underline.

It’s common to assume that since the hyperlink is taking you to “more information”, the source of that information must be valid and fair; this isn’t always the case. Readers have absolutely zero control over where that link is going to transport them - they can only control whether they click on it or not, and there’s no going back. Websites may have hidden agendas, strong political views, motivations to affect how people think. If we blindly click, read, and accept what hyperlinks are telling us, we risk being brainwashed by the specific words the writer wants us to be reading. Perhaps we should have a more cynical, critical attitude towards what we interpret from hyperlinked writing.

And remember the ease and convenience of hyperlinks I mentioned earlier? While that might be beneficial on some occasions, it might harm us in the long run, some researchers are now suggesting. The presence of simple links that take us straight to our desired destination is making us lazy, incompetent, and - all in all - bad researchers. Information is plated up and served to us, and we’re way more likely to take the easy option and use what we’re given, rather than continue fishing on the internet for other data which may, or may not, be more useful and relevant. We no longer have to think about what we want to know, and where’s best to find it: we just trust the link straightaway and move on with our lives. Does this mean that our standards of research in education and academia could be under threat?

Overall, the beauty of having a pathway cut through the internet on your behalf means you can access information quickly and simply. But on the flip side, this naturally cuts out a whole host of other websites and sources offering material you may actually prefer. Being told to “click here for more information” might be impacting upon our thought processes, too. The fact we no longer need to wade through websites for hours to find our answers means we no longer need to read as much, full stop. Linguists are now questioning whether this is damaging our ability to read conventional texts and follow complex arguments. The constant stimulus of clicking from page to page without completing a whole text is stunting our deep thinking - is that worth risking, for the sake of some lazy links?

Sources

Jones, R. H. & Hafner, C. A. (2012). Understanding Digital Literacies: A Practical Introduction. London: Routledge.

Images

https://www.webfx.com/blog/web-design/designing-hyperlinks-tips-and-best-practices/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Shakespeare

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/International_Tennis_Federation

https://www.telegraph.co.uk/travel/destinations/europe/united-kingdom/articles/best-uk-beaches/

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Secrets of Searching... Google Exposed

How long should I cook this chicken for? Google it. When was the Queen born? Google it. How does the internet work? You can even Google that. But behind the friendly façade of the world’s most popular search engine, there lie hidden processes determining what each and every one of us is selectively shown when we hit “Search” - and it’s a bit concerning.

Back in the stone age, before Google was even a thing (to be specific, the 90s), Larry Page and Sergey Brin, the two Stanford students who would later go on to be the search engine’s founders, invented the PageRank algorithm. Simply speaking, the algorithm assigned an “information value” to online data, based on the number and strength of relationships it has with other pieces of data and people. As Jones and Hafner say, “PageRank sorts search results in terms of relevance based on the number of other sites which link to them and the quality of these linkages”. So when you next Google something, remember that the top result is not necessarily the most relevant one for you: it is instead the most established, linked-to website.

“So what?��� I hear you cry, “Does that matter?” This algorithm, though a major player in Google’s world domination, is not the most frightening part. Since 2009 Google has also used personalised search features, with the aim of giving every user the most efficient experience - the internet, tailor made for you. Yes, everything you touch on the internet is monitored, recorded and analysed: your past searches, links you’ve clicked on, websites you’ve read. Using this info, the folks at Google determine which sites are probably most relevant to you (… or the person Google thinks you are). It considers your location, and combines data across other Google apps like Gmail and Google Docs. That’s right, it even searches through emails you’ve sent, to get a better idea of what you’re looking for.

For example, if I put “uni” into Google, I get this:

I haven't specified where - I haven’t even written the whole word - yet Google knows I’m probably talking about the University of Reading, since it uses my location and the fact that I’ve probably Googled it and been on the Reading Uni website about 1000 times in the past 2 years. Bit freaky.

Finally, Jones and Hafner claim that “searching for data is fundamentally a linguistic activity”, so a successful search needs the right words and phrases typed into the search bar. This input becomes vital data in itself: the words you type into the box, and the results you click on, are useful bits of information for advertisers to determine what ads are most appealing to you. Search terms are also analysed by businesses, journalists, anthropologists, historians and other scholars to measure trends in what people in modern society are interested in. In other words, with every letter you type online, you are providing search engines like Google with important information about yourself and your behaviour.

Remember - next time you Google “How to screen record on an iPhone” - Google’s already watching your every click.

- http://www.quotemaster.org/Google

Jones, R. H. & Hafner, C. A. (2012). Understanding Digital Literacies: A Practical Introduction. London: Routledge.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Digital communication: the good, the bad and the ugly

It might be second nature to us, but communicating with one another through technology has, according to Hafner and Jones, 5 big groups of pros and cons, called “affordances and constraints”. These are influences over doing, thinking, relating, meaning, and being.

“Being” - technology affects who we are

Different technological tools allow us to “be” different versions of ourselves: this can have both positive and negative implications.

Social media encourages us to adopt an identity, which we craft to be visible to all our friends or followers - in other words, a chosen representation of some aspects of your identity are highlighted, while others are deliberately disguised. This means users can actively control their image as it is projected to the world.

Privacy settings also allow you to share content with specific people while hiding it from others, to build multiple different images of “who you are”. A big issue with social media is the fact that the “perfect” lifestyles portrayed do not represent real, everyday life. Who ever posted a selfie on a bad hair day? This is a result of how technology allows us to design our own identity and present it, just as we like it.

Hafner and Jones say that if you use a mobile phone, you are automatically showing that you are a particular type of person: you can afford a phone, for a start. The type and age of your phone also indicates information about your identity - are you an iPhone or Android person? Latest model or 3 years old? This contributes to constructing your identity, and affects how other people view you.

The fact that technology influences our identity and “who we choose to be” can be both a positive and negative thing - while it allows us to explore and share our lives with other people, it’s also easy to create personas and online presences which are not true or authentic to the person behind them.

Jones, R. H. & Hafner, C. A. (2012). Understanding Digital Literacies: A Practical Introduction. London: Routledge.

3 notes

·

View notes