Text

JAZZ MOON RELEASE DATE: 5/31/2016

"A passionate, alive, and original novel about love, race, and jazz in 1920s Harlem and Paris — a moving story of traveling far to find oneself." — David Ebershoff, author of The Danish Girl and The 19th Wife

In a lyrical, captivating debut set against the backdrop of the Harlem Renaissance and glittering Jazz Age Paris, Joe Okonkwo creates an evocative story of emotional and artistic awakening.

On a sweltering summer night in 1925, beauties in beaded dresses mingle with hepcats in dapper suits on the streets of Harlem. The air is thick with reefer smoke, and jazz pours out of speakeasy doorways. Ben Charles and his devoted wife, Angeline, are among the locals crammed into a basement club to hear jazz and drink bootleg liquor. For aspiring poet Ben, the swirling, heady rhythms are a revelation. So is Baby Back Johnston, an ambitious trumpet player who flashes a devilish grin and blasts jazz dynamite from his horn. Ben finds himself drawn to the trumpeter–and to Paris where Baby Back says everything is happening.

In Paris, jazz and champagne flow eternally, and blacks are welcomed as exotic celebrities, especially those from Harlem. It’s an easy life that quickly leaves Bed adrift and alone, craving solace through anonymous dalliances in the city’s decadent underground scene. From chic Parisian cafés to seedy opium dens, his odyssey will bring new love, trials, and heartache, even as echoes from the past urge him to decide where true fulfillment and inspiration lie.

“Jazz Moon mashes up essences of Hurston and Hughes and Fitzgerald into a heady mixtape of a romance: driving and rhythmic as an Armstrong Hot Five record, sensuous as the small of a Cotton Club chorus girl’s back. I enjoyed it immensely. Frankly, I wish I’d written it.”—Larry Duplechan, author of Blackbird and Got ‘til It’s Gone

"Joe Okonkwo is an incredibly unique new voice and a very familiar one at the same time. His haunting style is reminiscent of Richard Wright, James Baldwin, and Gabriel Garcia Marquez. Jazz Moon is an elegantly written gift and a stunning literary debut. The characters are so vibrant and precise! The delicate plot about race, jazz, betrayal, and sex in early Harlem and Paris snatched me and held me hostage until the very last sentence." — Mary Monroe, author of The Upper Room and God Don't Like Ugly

"With commitment and compassion, the author deposits the reader back in time as he takes us on a roller coaster ride of human experiences and emotions. He conjures an alluring, nostalgic, sentimental, but also tragic atmosphere of black gay Harlem and Paris during the heyday of the Jazz Age." — James Smalls Ph.D., author of Gay Art and The Homoerotic Photography of Carl Van Vechten: Public Face, Private Thoughts

"Jazz Moon is an unexpected and original grand romance: sweeping, evocative, and colorful. Okonkwo is an author to enjoy now and watch in the future." — Felice Picano, author of Nights at Rizzoli and Like People in History

Read the first chapter of Jazz Moon

Pre-order

1 note

·

View note

Video

vimeo

“Enough to Live On”: Film Clip Featuring the Arts of the Harlem Renaissance

#Vimeo#217films#two17films#territempleton#michaelmaglaras#wpa#wpaart#indexofamericandesign#artandcrafts#thedepression#1935#holgercahill#franklinroosevelt#newdealart#enoughtoliveon#ttheartsofthewpa#aarondouglas

1 note

·

View note

Text

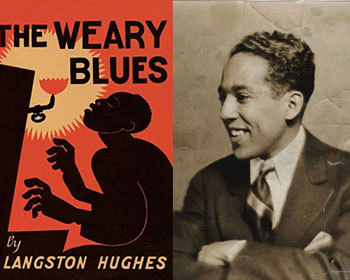

Jazz, Politics, and Poetry: A Review of Langston Hughes’s The Weary Blues.

Countee Cullen was known as the Poet Laureate of the Harlem Renaissance, but it was Langston Hughes who made poetry swing. Hughes was the first to capture the rhythms and cadences of jazz and blues in verse. He essentially invented the jazz poem. His jazz poems rollick, pulsate, syncopate on the page. The heartfelt essence of the blues swirls through them.

Reading Hughes's poems, you feel transported to a speakeasy or a cabaret or a revival meeting.

But, though plentiful, jazz poems comprise only one facet of The Weary Blues, Hughes's first collection originally published in 1926. From jazzy to sensual to intimate to race-conscious to outright political, the eclectic verses in The Weary Blues combine to ignite a poetic fire that sometimes rages, sometimes burns in quiet embers, and always illuminates.

Langston Hughes was one of the movers and shakers of the Harlem Renaissance and he published The Weary Blues at that movement's height. His racial and social consciousness were critical elements without which this collection could not possibly have been written. This is especially apparent in poems like the iconic "The Negro Speaks of Rivers" with its invoking of African geography and history:

I bathed in the Euphrates when dawns were young.

I built my hut near the Congo and it lulled me to sleep.

I looked upon the Nile and raised the pyramids above it.

And in "Proem" which starts off the collection, Hughes states, flatly: I am a Negro / Black as the night is black / Black like the depths of my Africa.

Africa, 1935, by Lois Mailou Jones

But the beautifully lush imagery of "The Negro Speaks of Rivers" often gives way to cold-eyed anger in poems like "The South," perhaps the collection's most bitingly political piece:

The lazy, laughing South

With blood on its mouth,

The sunny-faced South,

Beast-strong,

Idiot-brained.

The child-minded South

Scratching in the dead fire's ashes

For a Negro's bones.

This, and other poems like it, seethe with a dignified anger reminiscent of "If We Must Die," Claude McKay's 1919 reaction to the violent race riots of the era. But Hughes's political poems go further than McKay's. They thumb their noses at the perpetrators of racism, insulting them outright and in a way that is stylistically and aesthetically potent.

Black Gum, 1928, by Richard Bruce Nugent

The Weary Blues has its gentler side, too. In “Ardella,” Hughes calmly declares,

I would liken you

To a night without stars

Were it not for your eyes

I would liken you

To a sleep without dreams

Were it not for your songs.

And several short pieces like "Caribbean Sunset" provide quick, impressionistic flashes that pack a punch:

God having a hemorrhage,

Blood coughed across the sky,

Staining the dark sea red,

That is sunset in the Caribbean.

And the collection struts its sexy side(s). The blatant heterosexuality of something like "Natcha" (Offering / A night with me, honey / A long, sweet night with me) contrasts with the tender, mysterious, and tantalizingly possible homoeroticism of "Poem":

I loved my friend.

He went away from me.

There's nothing more to say.

The poem ends,

Softly as it began,--

I loved my friend.

Of course The Weary Blues has its jazzy side, its bluesy side, the side that lures you in, makes you wish you were in a Harlem dive listening to a gut bucket band while drinking bathtub gin. The title poem is a veritable ode to the sauntering speakeasy culture of 1920s Harlem:

Droning a drowsy syncopated tune,

Rocking back and forth to a mellow croon,

I heard a Negro play.

Down on Lenox Avenue the other night

By the pale dull pallor of an old gas light

He did a lazy sway . . .

He did a lazy sway . . .

To the tune o’ those Weary Blues.

With his ebony hands on each ivory key

He made that poor piano moan with melody.

O Blues!

Swaying to and fro on his rickety stool

He played that sad raggy tune like a musical fool.

Sweet Blues!

Coming from a black man’s soul.

The Jazz Singers, 1934, by Archibald Motley

Jazz poems like "Negro Dancers," "To Midnight Nan at Leroy's," and "To a Black Dancer in the Little Savoy" flaunt the shameless sexuality recently discovered and so in vogue in the 1920s. A 2015 reader may be taken aback by the numerous jungle references in these poems, but Langston Hughes was a writer of his time. You have to remember that this was the era when Duke Ellington got famous making "jungle music" at the segregated Cotton Club and Josephine Baker stormed Paris sheathed in a belt of bananas.

The Weary Blues is a beautiful collection. It captures so potently, so poignantly, the pain and beauty and excitement and terror of the African-American 1920s. Eclipsing all that pain, beauty, excitement, and terror is Langston Hughes’s--and indeed, the Harlem Renaissance’s--then-revolutionary thesis that black is beautiful.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Artist Spotlight: Richard Bruce Nugent

Audacious. Creative. Writer. Painter. Provocateur. These are only a handful of words to describe Richard Bruce Nugent (1906-1987), one of the most colorful members of the Harlem Renaissance movement. Nugent was, for years, one of the few openly-gay African-American artists. As a writer he contributed the famous (and scandalous) prose-poem "Smoke, Lilies and Jade" to the journal FIRE!! in 1926. The piece celebrates same-sex and interracial love.

Nugent's sensual artwork is populated with nude bodies and often rendered in black and white, mirroring his interest in interracial relationships in particular and black/white relations in general. One of his most striking pieces is Black Gum which depicts the lynching of an African-American. This was completed in 1928--eleven years before Billie Holiday recorded the iconic anti-lynching song "Strange Fruit."

For more information on Richard Bruce Nugent--and to see a multitude of his NSFW paintings--visit his official site.

Here is a gallery of Nugent's Harlem Renaissance-era work.

Opportunity Cover, 1926

Smoke, Lillies and Jade, 1926

Drawing of Mulatto #1, 1928

Drawing of Mulatto #2, 1928

Drawing of Mulatto #4, 1928

Black Gum, 1928

Dancing Figures, 1935

Untitled, 1936. The painting is signed “Gary George,” one of Nugent’s pseudonyms

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Artist Spotlight: Loïs Mailou Jones

The galaxy of great Harlem Renaissance artists is studded with stars. Archibald Motley, Richmond Barthe, James Van Der Zee, Palmer Hayden, Aaron Douglas, Richard Bruce Nugent, and Hale Woodruff are among them. Highy-successful women artists, sadly, are few. But among the women who achieved broad recognition, Loïs Mailou Jones shines brightest.

Jones was born in Boston in 1905, the child of accomplished parents. Her lawyer father was the first African-American to graduate from Suffolk Law School and her mother was a cosmetologist. As a teenager, she took evening classes at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts and worked as an apprentice in costume design. She had her first solo exhibition at the earnest age of seventeen. She earned a Bachelor's from Howard University in 1945 and did graduate work at Harvard and Columbia.

Because of racial discrimination, Jones's white friend Céline Tabary often entered her artwork in competitions. And, again because of discrimination, when she won an award she would ask that the prize be mailed to her for fear of being disqualified if her race was known.

According to her official web site, "Loïs was the first and only African American to break the segregation barrier denying African Americans the right to display visual art at public and private galleries and museums in the United States. One of her greatest accomplishments was being the first African American to have a solo exhibition at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston."

She was the only African-American woman painter to achieve international fame in the 1930s and 1940s.

Loïs Mailou Jones had a long career and a long life. She was one of the longest living artists of the Harlem Renaissance. She died in 1998 at the age of ninety-two.

Her art covers a wide range: from landscapes and portraits to textile designs. Much of her most exceptional work centers on African themes and heritage. Her paintings reside in the permanent collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Museum of American Art, Boston Museum of Fine Arts, and the National Palace in Haiti.

Here is a gallery of her Harlem Renaissance era paintings.

The Flight of Love (Rodin), 1923

Nude Study, 1925

Japanese Waterfall, 1925

Negro Youth, 1929

Sedalia, North Carolina, 1929

Brother Brown, 1931

Portrait of Hudson, 1932

The Ascent of Ethiopia, 1932

Africa, 1935

1 note

·

View note

Text

Book Review: Passing by Nella Larsen

1929 must have been the year of the African-American skin complexion novel. Two were published that year and they couldn't have been more different.

The Blacker the Berry by Harlem Renaissance bad boy Wallace Thurman concerns intra-racism: racism from blacks toward blacks, in this case toward blacks who are very dark-complexioned. Berry's protagonist (a thinly-veiled portrait of Thurman himself) is a young woman whose life is misery because of her very dark color. Other blacks laugh at her, shun her, or refuse to hire her. The only romantic love she can find is with users and losers. The novel's title is intentionally ironic: in the world of Berry, there is nothing sweet about being dark-complexioned. A person "cursed" with such skin tone is essentially an outcast in the black world.

The other skin complexion book from 1929 is probably better known and has been much discussed in recent years. Passing by Nella Larsen is Berry's thematic and stylistic polar opposite. It concerns blacks so light-skinned, they are able to operate fluidly in the white world without anyone suspecting their racial identity. Thus, those who "pass" can access the conveniences and resources typically available only to whites while simultaneously avoiding the humiliating pitfalls of racial discrimination.

The story is told through the eyes and voice of Irene Redfield, a black middle-class woman. Though light enough to pass, Irene lives almost entirely within the black world where she maintains an active presence among Harlem's social, artistic, and intellectual circles. At a time when blacks could be turned away from public facilities on the basis of race, Irene utilizes her ability to pass only "for the sake of convenience, restaurants, theatre tickets, and things like that." On a trip to her hometown of Chicago, she passes in order to patronize a swanky rooftop restaurant and escape the seething summer heat. Quite by accident, she runs into Clare Kendry Bellew, a girlhood acquaintance with whom she had lost contact several years earlier. With her pale skin and blond hair, Clare is also able to pass but, unlike Irene, she has discarded her black identity and completely reconstituted herself in the white world, going so far as to marry a white man who has no knowledge whatsoever of her racial background.

Two things fascinate Irene Redfield. The first is Clare's racial reinvention. Irene wonders "about this hazardous business of 'passing,' this breaking away from all that was familiar and friendly to take one's chance in another environment, not entirely strange, perhaps, but certainly not entirely friendly." The other thing that fascinates Irene is Clare herself. A not-so-subtle sexual desire on Irene’s part flutters through descriptive passages like this one:

[Clare had] always had that pale gold hair, which, unsheared still, was drawn loosely back from a broad brow, partly hidden by the small close hat. Her lips, painted a brilliant geranium-red, were sweet and sensitive and a little obstinate. A tempting mouth. The face across the forehead and cheeks was a trifle too wide, but the ivory skin had a peculiar soft lustre. And the eyes were magnificent! dark, sometimes absolutely black, always luminous, and set in long, black lashes. Arresting eyes, slow and mesmeric, and with, for all their warmth, something withdrawn and secret about them.

The subplot delves into Irene's flailing marriage to a successful black doctor (too dark to pass) who is miserable in America and longs to resettle in more racially tolerant Brazil. Much of the book centers on Irene's misguided attempts to maintain control over her would-be errant husband and keep his rogue mind off Brazil.

But it is, by far, Irene's fascinations with Clare that drive Passing, especially as Clare attempts to reinsert herself into the black world--a feat as challenging as it is dangerous considering her marriage to a ravenously racist white man. In the novel's most chilling scene, Clare introduces her wealthy banker husband, John Bellew, to Irene and another black woman who also passes. Bellew, blissfully ignorant of the racial background of any of the women in his presence (including his wife), calls Clare by his nickname for her: Nig. He nonchalantly explains how he came to gift her with this term of endearment: "When we were first married, she was as white--as--well as white as a lily. But I declare she's gettin' darker and darker. I tell her if she don't look out, she'll wake up one of these days and find she's turned into a nigger." When a horrified Irene asks Bellew if he dislikes Negroes, he clarifies with "You got me wrong there, Mrs. Redfield. Nothing like that at all. I don't dislike them, I hate them." He then offers that blacks "give me the creeps" and refers to them as "black scrimy devils." Though furious, Irene is too terrified to stand up to him and reveal herself as black because doing so would endanger herself and Clare. Guiltily contemplating the incident later, she wonders why she "failed to take up the defense of the race to which she belonged."

Above: The Octoroon Girl (1925) by Archibald Motley

The incident exposes the danger of passing. It also begs the question: why would anyone risk such danger and submit--voluntarily--to racial humiliation on a daily basis as Clare has chosen to? Irene addresses this with her "for the sake of convenience" answer. But Clare's reason is more stark: "Money's awfully nice to have. In fact, all things considered, I think...that [passing is] even worth the price."

Both answers reinforce Passing's dual critique of blacks who abandon the black world (even temporarily, as Irene does) and of a racist white America where, in order to experience the rewards of living in a rich country, blacks (at least those with the right skin tone) must pretend to be someone they are not. This, in turn, raises an elephant-in-the-room question: If a black person possesses no recognizable physical traces of blackness, then is that person really black? From a strictly biological perspective, does that person actually belong to the black world that they have "abandoned"?

Larsen does not directly pose this question in her novel, but the facts of her life pose it. Nella Larsen's father was an Afro-Caribbean from the Danish West Indies. He was part black, part Danish, but it is possible that he never identified as black. Her mother was Danish. After her father disappeared from her life, Larsen's mother married another Danish man with whom she had a child. Novelist/playwright/essayist Darryl Pinckney has written:

As a member of a white immigrant family, she [Larsen] had no entrée into the world of the blues or of the black church. If she could never be white like her mother and sister, neither could she ever be black in quite the same way that Langston Hughes and his characters were black. Hers was a netherworld, unrecognizable historically and too painful to dredge up.

After she vanished from Harlem's literary scene, some acquaintances suspected that Nella Larsen herself may have passed for white.

Passing is rich, heady stuff and not just because of its plot (well-paced, well-crafted, a page-turner) or its writing style (elegant, economical prose). Fitting neatly into the didactic and propagandistic realm approved of and championed by "establishment" Harlem Renaissance figures like W.E.B. Dubois, Passing's richness also results from the plethora of thorny, uncomfortable issues Larsen courageously and systematically confronts: race, gender, sex, class. The novel is studded with important questions about belonging and identity and loyalty and community. Like all truly good novels, the important questions never get fully answered, but linger and resonate long after you've put the book down.

159 notes

·

View notes

Text

Music Review: Bessie Smith: The Collection

Empress of the Blues Bessie Smith's recording career began in 1923 and ended in 1933. Her tragic early death notwithstanding, it was comparatively short career considering the longevity of fellow jazz legends like Louis Armstrong or Duke Ellington whose output spanned fifty-plus years. Even so, Smith's wealthy legacy encompasses over one-hundred-and fifty excellent sides. Bessie Smith: The Collection provides an astute cross section of the Empress's varied recordings.

Her 1923 smash debut recording of "Downhearted Blues" leads off the collection. Accompanied by a solo pianist (the prolific Clarence Williams, a jazz legend in his own right), Smith's raw melancholy combined with her artistry creates a sound and a musical experience that make it easy to comprehend how "Downhearted Blues" sold an earth shattering 780,000 copies in its first six months of release.

This compilation also contains her standard-bearing rendition of W.C. Handy's "St. Louis Blues" featuring a young Louis Armstrong who provides vibrant respones to Bessie's plaintive calls. The song leaves you entranced, in awe, yearning for more.

youtube

In addition to classic blues, Bessie Smith: The Collection offers a mischievous glimpse into Smith's lighter, naughtier side. In "Do Your Duty," she playfully warns her man:

If my radiator gets too hot,

Cool it off in lot of spots.

Give me all the service you've got

Do your duty.

If you don't know what it's all about,

Don't sit around my house and pout.

If you do you'll catch your mama tippin' now

Do your duty.

The song's tongue-in-cheek sexual innuendo drops dead in comparison to "Empty Bed Blues" which leaves absolutely nothing to the imagination:

He poured my first cabbage and he made it awful hot,

He poured my first cabbage and he made it awful hot.

When he put in the bacon, it overflowed the pot.

These "dirty" songs reflect the more liberated sexual consciousness of the 1920s--an era in which people began to revel in defying convention and indulging in all the things respectable society wasn't supposed to: alcohol, sex, drugs, and, yes, listening to jazz. Also central to the new Jazz Age enlightenment was woman's burgeoning power and independence. Hollywood actresses like Mary Pickford, Norma Shearer, and Clara Bow had attained unprecedented power and wielded it prodigiously. Power wasn't exclusive to whites. Black female entertainers like Ethel Waters, Josephine Baker, and Bessie Smith herself never hesitated to exert their hard-won influence. This independent spirit pervades many of Bessie's songs. In "You've Been a Good Ole Wagon," she gruffly informs her man that she's moving on because he no longer satisfies her. In "I Ain't Gonna Play No Second Fiddle," she tells her cheating man that two can play that game:

Caught you with your good-time tramp,

So, now I'm gonna put out your lamp.

Oh, poppa, I ain't sore.

You ain't gonna mess up with me no more.

I'm gonna flirt with another guy,

Then you're gonna hang your head an' cry.

Ain't gonna play no second fiddle 'cause

I'm used to playin' lead.

Smith's assertive declarations on these records are rendered effective and affecting by her majestic musical sensibilities and bottomless emotional reservoir. When she says she won't play second fiddle, you don't doubt for a moment that she means it.

The compilation finishes off with one of Smith's best-known recordings: 1933's "Gimme a Pigfoot; a fitting finale since it was her very last record. It could be argued that "Pigfood" sums up the 1920s along with Smith's career. The song depicts a raucous Harlem rent party--the kind now acknowledged as one of the iconic symbols of the Harlem Renaissance. If any one song encapsulates the frenzied, jazzy, throw-caution-to-the-wind aspect of the Harlem Renaissance, this is the it.Bessie lets loose in what is one of her most spirited performances, barely taking a breath during the fast-paced song and once again asserting that powerful, take-no-prisoners attitude and not a little bit of the mischievous persona rippling through some of the more playful songs in her oeuvre.

Gimme a pigfoot and a bottle of beer.

Send me a gate I don't care.

Feel just like I want to clown.

Give the piano player a drink

Because he's bringing me down

He's got rhythm yeah, when he stamps his feet.

He sends me right off to sleep.

Cheek all your razors and all your guns.

We're gonna be arrested when the wagon comes.

Gimme a pigfoot and a bottle of beer

Send me 'cause I don't care.

Bessie Smith's life and career may have been cut short, but she left behind a treasure trove of recordings. According to Chris Albertson who wrote the liner notes for this collection (as well as an excellent biography of Bessie first published in 1972), by the time of her last recording session, "she had made 156 sides, not one of them less than very good, most of them excellent, and some of them true classics."

Bessie Smith: The Collection shows off the absolute best of the eternal Empress of the Blues.

0 notes

Photo

In a lyrical, captivating debut set against the backdrop of the Harlem Renaissance and glittering Jazz Age Paris, Joe Okonkwo creates an evocative story of emotional and artistic awakening.

On a sweltering summer night in 1925, beauties in beaded dresses mingle with hepcats in dapper suits on the streets of Harlem. The air is thick with reefer smoke, and jazz pours out of speakeasy doorways. Ben Charles and his devoted wife, Angeline, are among the locals crammed into a basement club to hear jazz and drink bootleg liquor. For aspiring poet Ben, the swirling, heady rhythms are a revelation. So is Baby Back Johnston, an ambitious trumpet player who flashes a devilish grin and blasts jazz dynamite from his horn. Ben finds himself drawn to the trumpeter--and to Paris where Baby Back says everything is happening.

In Paris, jazz and champagne flow eternally, and blacks are welcomed as exotic celebrities, especially those from Harlem. It’s an easy life that quickly leaves Bed adrift and alone, craving solace through anonymous dalliances in the city’s decadent underground scene. From chic Parisian cafés to seedy opium dens, his odyssey will bring new love, trials, and heartache, even as echoes from the past urge him to decide where true fulfillment and inspiration lie.

“Jazz Moon mashes up essences of Hurston and Hughes and Fitzgerald into a heady mixtape of a romance: driving and rhythmic as an Armstrong Hot Five record, sensuous as the small of a Cotton Club chorus girl’s back. I enjoyed it immensely. Frankly, I wish I'd written it.”—Larry Duplechan, author of Blackbird and Got 'til It's Gone

Jazz Moon is available for preorder.

0 notes

Quote

Harlem had been hit by a hurricane: It was raining cats and jazz.

From the novel Jazz Moon by Joe Okonkwo

113K notes

·

View notes