Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

When I initially saw the word “parigüayo” appear in Oscar Wao and learned of its meaning, I could not help but become overpowered by my giddiness! The invocation of an infamously overpowered comic book character in the context of this book was surely no mistake, right? How could Oscar, an infamously nerdy lover-of-comics, possibly come up in the same sentence as a word which roughly translates to “watcher” and by mere coincidence? Here you have a book hinged on the main character’s niche obsession with comic books invoking a name that I myself nerdily associate with the deep-lore of Marvel Comics.

For the purpose of briefly contextualizing my excitement and/or the relevance of the seemingly arbitrary invocation of the term “watcher,” in the Marvel Comics universe, the Watchers are noted as being one of the oldest species in existence. Their sole purpose for being is to observe and cultivate all knowledge across the known multiverse and they have a strict “isolationist” policy meaning they are prohibited from interfering with the events they compile. In short, they are passive archivists, bound by cosmic “law” to not intervene in the affairs of mortals. This policy was implemented after the Watchers made an attempt, in good faith, to bestow the knowledge of the multiverse onto a race of beings called the Prosilicans. However, the knowledge that they were endowed with led to the creation of nuclear weapons with ended in a catastrophic conflict. The Watchers were subsequently blamed for the giving the Proscilicans knowledge they were not yet prepared to handle, and enacted their stringent policy of no intervention. Despite this though, the recurring Watcher character name Uatu consistently interferes with the superhero adventures of Hulk and the Fantastic Four on several occasions, aiding even in the destruction of their enemies at some points. At one point, Uatu is put on trial, where it is revealed that the Watcher has broken his non-intervention pact hundreds of times throughout the multiverses history. Here, it is also revealed that the Watchers are bound to their policy of non-intervention by a force known as Fulcrum, to which there are consequences for disobeying. Oddly enough, though, the other Watchers have themselves interfered in the events of other civilizations' in the Marvel universe, most notably in the face of apocalypse or world-ending events. Basically, the contingencies on which they can break their own law are determined by them, in specific instances where they deem their intervention necessary to continue being, well, Watchers. I think this is essentially the idea that in order to watch the universe, there needs to first be a universe to watch. Now, here’s Diaz’s first use of the of the term “parigüayo:” “Sophomore year Oscar found himself weighing in at a whopping 245 (260 when he was depressed, which was often) and it had become clear to everybody, especially his family, that he’d become the neighborhood parigüayo.* Had none of the Higher Powers of your typical Dominican male, couldn’t have pulled a girl if his life depended on it. Couldn’t play sports for shit, or dominoes, was beyond uncoordinated, threw a ball like a girl. Had no knack for music or business or dance, no hustle, no rap, no G. And most damning of all: no looks. He wore his semikink hair in a Puerto Rican afro, rocked enormous Section 8 glasses—his “anti-pussy devices,” Al and Miggs, his only friends, called them—sported an unappealing trace of mustache on his upper lip and possessed a pair of close-set eyes that made him look somewhat retarded. The Eyes of Mingus. (A comparison he made himself one day going through his mother’s record collection; she was the only old-school dominicana he knew who had dated a moreno until Oscar’s father put an end to that particular chapter of the All-African World Party.) You have the same eyes as your abuelo, his Nena Inca had told him on one of his visits to the DR, which should have been some comfort—who doesn’t like resembling an ancestor?—except this particular ancestor had ended his days in prison.” (Diaz, 35-6)

And the definition, again by Diaz:

“The pejorative parigüayo, Watchers agree, is a corruption of the English neologism “party watcher.” The word came into common usage during the First American Occupation of the DR, which ran from 1916 to 1924. (You didn’t know we were occupied twice in the twentieth century? Don’t worry, when you have kids they won’t know the U.S. occupied Iraq either.) During the First Occupation it was reported that members of the American Occupying Forces would often attend Dominican parties but instead of joining in the fun the Outlanders would simply stand at the edge of dances and watch. Which of course must have seemed like the craziest thing in the world. Who goes to a party to watch? Thereafter, the Marines were parigüayos—a word that in contemporary usage describes anybody who stands outside and watches while other people scoop up the girls. The kid who don’t dance, who ain’t got game, who lets people clown him — he’s the parigüayo. If you looked in the Dictionary of Dominican Things, the entry for parigüayo would include a wood carving of Oscar. It is a name that would haunt him for the rest of his life and that would lead him to another Watcher, the one who lamps on the Blue Side of the Moon.” (Diaz 423)

I related this “on again, off again” relationship to intervention to the idea of United States occupancy of the Dominican Republic, and their track record of neo-imperial occupancy. The United States, an allegedly peaceful, neoliberal utopia, which stands alone in the world in their ongoing quest for peace, themselves alone decide the terms and condition of said peace. “Democracy” and “freedom” are conveniently defined by whatever the goals of the U.S. are, and whatever entity’s goals don’t align with their perfect formula for “peacekeeping,” consider said entity enemy number one of the United States from that point forward. The U.S. cannot risk their grip on the world to be loosened by any means, and that means establishing their concept of “ideal rule” across the globe under the guise of liberating less fortunate nations and peoples. Similarly, the Watchers decide when they must intervene, and refuse to let humans run their course. It’s interesting to apply this concept to Oscar, who like the United States forces in a foreign land, is an outsider to his environment. Oscar’s presence is also unwelcome, like the United States and intimidating/unsettling, like the Watchers. Surely, the knowledge that Oscar possesses is alien and inconceivable to “mere mortals” Oscar also cultivates the knowledge of unseen worlds, and his niche obsessions are similarly “archived” by his hyper-active selective memory for nerdy memorabilia. Oscar also doesn’t “intervene” in the parties of his youth, or with the girls in his life, he merely watches, and philosophizes about his inability to do so. When Oscar does intervene, though, is in his daydreams, in his imagined apocalyptic scenarios, similar to the Watchers, who only interfere with the affairs of mortals when it risks destroying the world, or the United States, when they fear their way of life is “under threat.” Finally, this is a bit of a stretch, but the idea of Fulcrum, a cosmic force set in motion without your control, that bears consequences for you actions against it, kind of sounds like Fuku. Fuku cursed the West for their exploitation of the Americas, Oscar was cursed to a life of misfortune because his neglect of his childhood love affair, and Fulcrum binds the Watchers to a sort of “curse” if they break it’s rules.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

In all my readings of Watchmen, I have never developed as full an analysis of the first Silk Spectre as you have here. I agree she is something of an underdeveloped character, at least as far as the story’s A-Plot is concerned. I’ve always woven her story into the overall theme of “nostalgia” that Veidt’s lifestyle products also touch on. However, after your post, I feel like if you, for a moment, remove that overarching idea, and focus just on the relationship between a mother and a daughter, two women from very different eras, it surprisingly opens up our eyes to new political analysis. It’s interesting to compare her history and development with that of her daughters,’ because they could not be more different. Laurie is very determined and independent, which seems to be reflective of the era Sally potentially laid the groundwork for. This isn’t to say Sally is a feminist icon, but I think Sally’s position as the first female hero, even though her iconography was commodified, is essential to the more feminist figure that Laurie embodies. On the contrary, Sally seems so complacent and unwavering, fixed on her appearance to such a degree she buys into the rhetoric that back’s victim blaming and excuses assault. On one hand, Laurie is unable to outrun her past because of her refusal to confront it, and therefore acknowledge how far women have come since her mom’s “moment”. On the other hand, there is the original Silk Spectre which has cemented herself as a cultural sex icon in this world, and she cannot escape that past solely due to her chasing after it, and her refusal to let it go. She is bitter and resentful about how things went with Laurie, because Laurie saw past the “mechanism” that controlled much of her mother’s life and blamed her for the abuse she dealt with. This I think plays into the idea of fate, and shows that ultimately, neither of the character’s, despite the fact that they kind of behave to spite the other, have any real choice over where their respective future lead them. I don’t know that I agree with this idea of fate, because to me it seems like it promotes the idea that history moves in cycles, and that it presses on necessarily without our contribution or without our activity. It maybe presupposes, that the “course of the universe” defaults to what is morally just. But still an interesting thing to consider, I suppose.

Silk Spectre: How Do You Exist?

One of the things that I definitely latched onto my second time around reading Watchmen was how the women weave through this narrative. That is probably mostly because of the slant to which we did read the comic in this course, but I feel as though the Silk Spectre is presented simply as backstory when she has much deeper implications as a character.

I would like to say I feel as though Silk Spectre’s name alone is telling – it was obviously chosen in part to suggest the “washed up” nature of her superhero, as a ghost is something dead from the past that haunts the present. I think it was already mentioned in class today, but it also suggests only ever seeing her costume and not the actual person wearing. A spectre makes me thing of a ghost obviously, but it also makes me think of the way in which we view ghosts: as these visions of light. The silk is revealed by this vision of light, as is Silk Spectre, but rather, it seems to stop there.

If you google the word “spectre,” though, you come up with another defintion: “something widely feared as a possible unpleasant or dangerous occurrence.” This is obviously why she chose her own name, to have the sexy and scary elements, but Silk Spectre remaining such a large part of the present narrative also suggests the sort of sexism inherent in what she represented to the generation she thrived in as still being alive in the generation Laurie is in. This is obvious in numerous ways that Silk Spectre’s ghost of a superhero, and the iconography of 40′s/50′s bombshell womanhood, refuses to leave the present narrative. Laurie’s history as being a superhero still haunts her, as does the sexist attitudes about women as revealed by people like Rorschach (explicity) and Dr. Manhattan (implicitly).

I also think this second definition comes to represent the assault that Sally was victim to at the hands of the comedian. It still lives in the present, even if not born by it, in the form of Laurie. Womanhood seems to be defined by contrast here, as Laurie’s womanhood is defined by her own mother’s. Manhood seems to function in the same way, as in the present for someone like Dan it is defined by men like Nite Owl and the Comedian in the past. This toxic masculinity of violence, suppressing women, and having a “take what’s mine fuck everyone else” attitude is something that is directly supported by the U.S. Government in continuing to employ the Comedian even after vigilantism is outlawed. The systemic nature of toxic masculinity that enforces toxic femininity haunts the present for people attempting to assert their woman-and-manhood like Dan and Laurie in the present.

All of these things combined ask how do you exist? I think it asks this directly because of the way in which Laurie’s entire existence is questioned at the upheaval of finding out her father is the Comedian. The 80′s were a time in which the Women’s Liberation movement greatly stalled under Reagan due to attitudes of living in a post-sexist society because of advancements made in the 60′s and 70′s for women (just google Phyllis Schlafly, to which the Aunts in The Handmaid’s Tale are based on). I think Laurie represents looking at how do things like post-sexism exist, and how does sexism exist and haunt us in the present in the first place? How does toxic masculinity shift and then exist in the present from how it existed in the past? How do women like Sally and Laurie differ in opportunity between their respective time periods? I think these are important questions that could probably fill a full essay.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

“So God created man in his own image, in the image of God he created him”

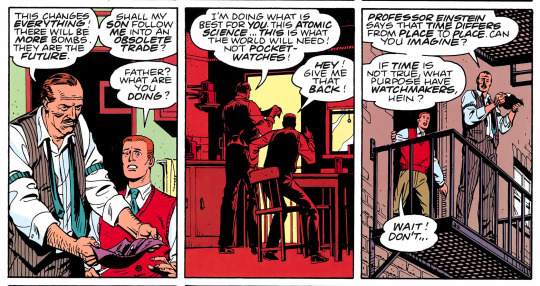

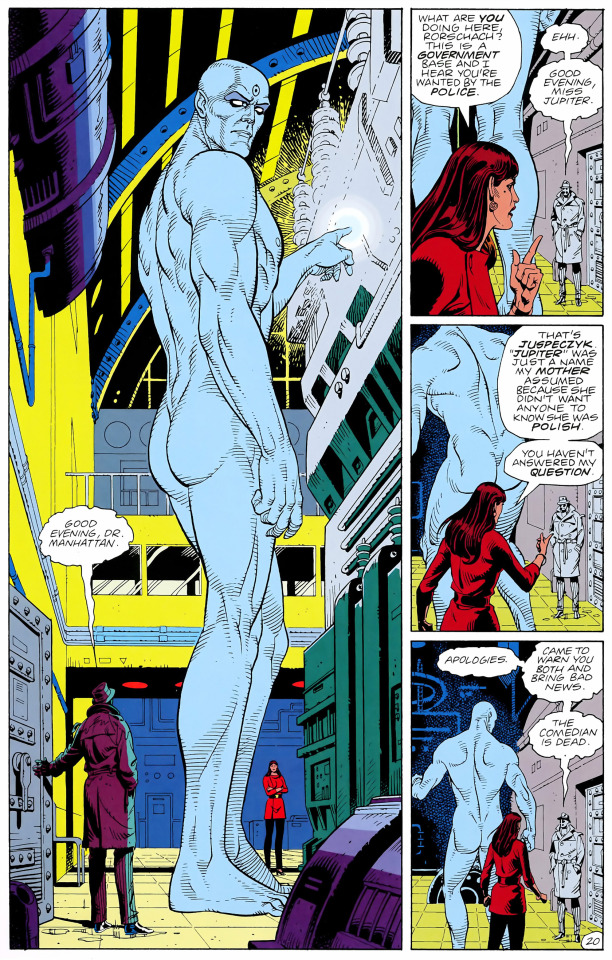

Dr. Manhattan, himself, talks about his transformation as a sort of “death and rebirth,” because he marks this event as the sort of turning point in his life, the moment when his newfound relationship to external and internal sensations, and to life and death drove a wedge between his experiences (consciousness) and his humanity (material manifestation). Jon’s initial fascination with watchmaking is very revealing in terms of who he would ‘become” as Manhattan, of what a person like him would make of himself when endowed with the abilities of a god.

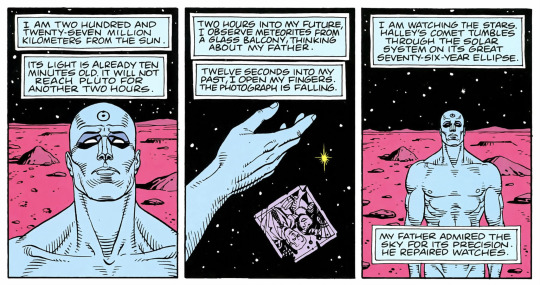

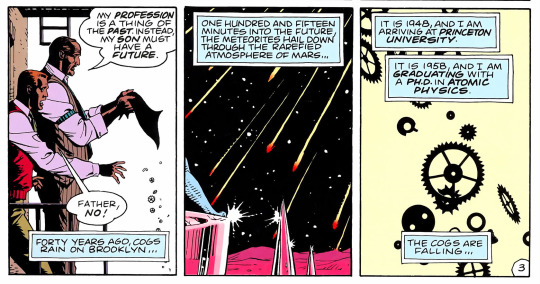

Throughout Chapter IV, there is a recurring image of a black sheet of velvet which has cogs laid out across its surface, and the image is intercut between other temporally nonlinear story panels. The image is meant to draw a resemblance between the stars (as components of a larger “mechanized” universe) that dot the chapter’s background and the watch’s cogs (as components of a literal machine). Watches often have a peculiarly significant bearing on Manhattan’s fate, as each step that he identifies as having led to him being locked in the intrinsic field generator is connected to his fascination with repairing watches. The aforementioned image of the cogs first appears on the chapter's second page, and follows after a panel of Dr. Manhattan fondly recalling his father, formerly a watchmaker, who "admired the sky for its precision.”

Manhattan says this while he himself is found gazing up at the stars on the surface of Mars, trying to find a “name [for] the force the put them in motion” (IV, 2). This nameless force is to the stars what Manhattan is in relation to the “cogs” of the watches he fixes; he sets them in motion, and transforms them from atomized “parts” into an interconnected system. The chapter’s title, “Watchmaker” is fittingly juxtaposed with Manhattan pondering what is behind the creation and existence of the universe, almost “answering,” his question; whatever “force” is behind the “setting in motion of the stars,” likely resembles him, as he is the closest thing to a legitimate deity, or god, in the story.

This sequence of combined images of and narration by Dr. Manhattan relates the character to his father, and uncovers the reasons for Manhattan’s fixation on “finer details,” on the way in which individual components interact and bring greatly complex “things” (i.e from the vast universe to finely tuned watches) into existence. To Manhattan, there is no discrepancy between the atomized components of a “thing,” and the “thing” itself which is made up of those components, because that “thing’s” existence is contingent on the interrelationship of it’s components, the relationship is direct, and therefore Manhattan views things in their totality, he sees the “bigger picture” as it were.

The next time this image of the cogs appears is on the following page, when Manhattan recalls the very moment in which his dreams were crushed by his father. A 16 year old Jon Osterman sits, fidgeting with a watch he is projected to fix. However, after hearing of the invention of atomic bomb following it’s “successful” deployment on Hiroshima, Jon’s father insists his son pursue sciences in atomic energy and forgo the family trade of watchmaking.

His father then dumps the pieces of the watch he was working on over their balcony, the final twist of the knife, so to speak. As the cogs fall, the following panel jumps to 15 minutes into Manhattan’s future on Mars, where he watches as a meteor shower grazes the atmosphere of the red planet. This again draws similarities between the meteorites (shooting stars as they are often misidentified), celestial bodies that interact with one another to form of the whole of the universe, and cogs, which are obviously components of a watch. With what we know of Manhattan’s characterization up to this point in the story, we can see how his particular fascination with the intricate beauty of minutia has lended itself to his development.

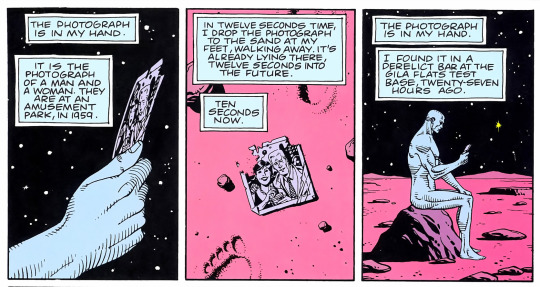

At the end of the previous chapter, Manhattan is abruptly confronted with accusations that his atomic structure may be linked to the cancer found in Moloc, Janey Slater, among others who have found themselves “entangled” in Manhattan’s life. Here, after an interrogative bombardment on the part of the press, Manhattan is faced with a unique of vulnerability; he is overwhelmed, and for once he doesn't have an immediate, off-hand solution. Nothing that he can “materialize” out of thin air will be of any use to his current predicament. His omnipotence is made useless, and he breaks down because of his lack of foresight and readiness. More interesting, though, and more telling of his exact character, is his response.

After his meltdown he first undresses from his suit, which was more or less a "human costume" for the sake of his on-air appearance. He then teleports to Gila Flats, New Mexico, to revisit where he first met Janey, as the invocation of her name surely put the rest of his life in perspective and had him waxing philosophically about his past. He grabs an old photograph of the two of them before teleporting to Mars, where he reminisces on Janey and their relationship, the first time he was introduced to her, when he touched her hand at the moment she bought him a drink. Notice in his retrospective that he remembers the particular details of the situation that consolidate the image of his memory. This is reflective of how a watchmaker makes their living; looking at the whole of the watch will tell you little in terms to what need’s to be fixed, or what exactly has broken. You must put into perspective the exact mechanisms that allow the watch to function, or in this case which prevents the watch from functioning.

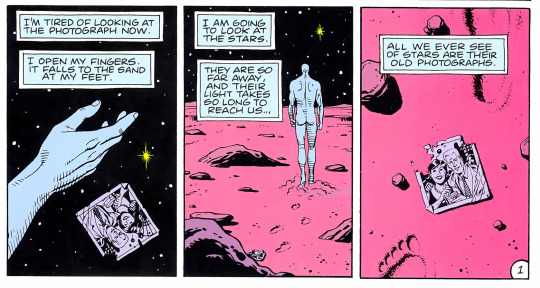

When he grows tired of looking at the photo, his attention shifts to the stars, where he ponders their existence and remarks that they are merely "old photographs" of what they once were; by the time their light reaches us, they are gone and forgotten about by the void of the universe. Notice how throughout this sequence, while he appears to have a photographic memory that picks up on every detail, he actually has a tendency to focus in on things he personally fines "fascinating," or what he regards as simply beautiful. This is a defining characteristic of Manhattan, I would contest, as it essentially results in his “undoing,” or his detachment from humanity, keeping him distanced from the human experience.

Manhattan is caught up with and sort of “stuck on” the necessary components of the “things” (i.e., cogs as they relate to watches, the physical beauty of his former and contemporary lovers, old photographs of his personal favorite memories, etc.) constitute his world. In his moments of awestruck wonder and analysis, he often ends up looking at the world around him for so long, that he is only able to see past it. In trying to understand the exact function and nature of larger “things,” he ends up missing the entire “point.” This reveals the flaw of Manhattan’s “godliness,” that cannot merely "be" or exist as an all-powerful, all-seeing, and all-being figure, and it has clearly contributed to his now broken and depressive mindset. It his not despite his “extra-normal” perception and senses that Manhattan is no longer able to find pleasure in his favorite activities, but is, ironically enough, because of these superpowers. His abilities work insofar as they provide him an unparalleled opportunity to get closer to the stars than any human could ever dream of, however this power does not, still, allow for him to fully understand their essential nature or origin or overall place in the universe as a whole; he fails to see past the "bigger picture,” even as a god.

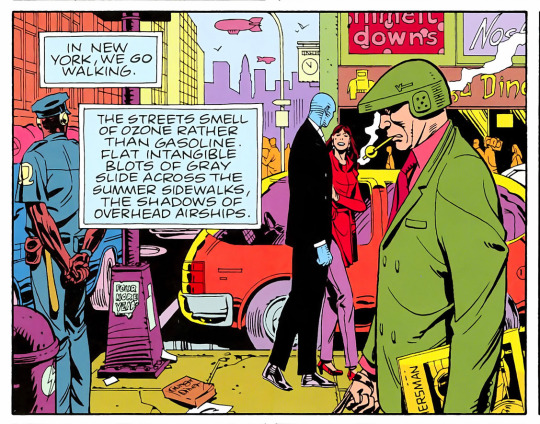

Dr. Manhattan, in the same vein of a traditionalist, Judeo-Christian interpretation of God, has shaped the world (and as a consequence, forged the path of humanity) in his image. His “creations” are reflective of how he, an omniscient, omnipotent, and omnipresent being, operates in a world composed of crude matter. The radical progress in scientific, political, and social developments that America has made as a result of the arrival of Dr. Manhattan are in many ways aesthetic: new and shiny. They are upgraded models of American lifestyles and traditions: the roasted, four-legged chicken, spotted in the first chapter, the futuristic-looking cars, as well as the airships that dot the background of many of the story's panels, all of these progressive technological steps "forward" contribute to society perhaps feeling comforted, and safe; even Manhattan, especially as a means of preventing the escalation of nuclear war with the Soviet Union, is a sort of pillar of security and protection.

However, these inventions reflect Manhattan's detachment from the true needs of humanity, which very obviously transcend the likes of material indulgences. In the midst of a Cold War, Manhattan's otherworldly might and power have produced what are essentially bandaids, comparatively speaking. In this way, these benchmarks of progress that have cemented themselves into the alternate history of Moore's Watchmen also mirror Dr. Manhattan's relationships, and his troubles with commitment, intimacy, attachment, and sociability,

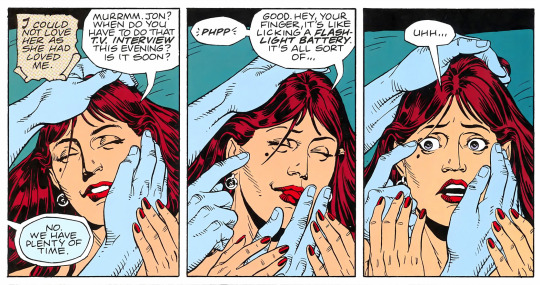

Manhattan's inadequate solutions to the ails of man are similar to his failure to reciprocate intimacy with Laurie Jupiter in the beginning of Chapter III, when he is seen sort of "cloning" himself to tend to Laurie while he is meanwhile duplicitously working on one of his many science experiments in the next room over. In both these instances, Manhattan creates a sort of distraction, one that he is able to imagine from the limited perspective of an at once out of touch and omnipotent being, one that will aesthetically please the American people and/or Laurie, but one that also fails to get to the root of the issues eating away at them.

With Laurie, Manhattan assumes, two being better than one in his mind, that his partner won't mind his mental absence from them engaging in intimacy. Manhattan's intervention in society in general. as well as his interpersonal relationships with others, have worked merely to cover up the blemishes of the more deeply rooted issues by means of fast and fancy cars, genetically modified chickens, and kinky threesomes with clones. These inventions and gestures function as extensions of and, in many ways, metaphors for Dr. Manhattan’s mode of being; their inadequacy in terms of accurately diagnosing and treating the problems humanity is faced with prove that image of Manhattan as a Nietzschean ubermensch that society at large has come to associate him with is ill-conceived.

Speaking more on Dr. Manhattan as being perceived by the public as the "Superman," the character largely exists as a symbol of the best a man can be, a sort of “upgrade” from the prototypical model of “a man.” This indicates that he still possesses and is affected by the same woes and shortcomings that effect humans. This is reflected in his tendency, even prior to Osterman's transformation into Manhattan, to neglect his significant others and prioritize his scientific endeavors and pet projects over their needs. In this sense, we can determine he may not necessarily meet the qualifications for being a god, but an extraordinary man endowed with the ability of a god, and more importantly, left with the particularly human faculties to wield and process these abilities. Manhattan's "powers" certainly give him extra-human senses, such as his heightened perception of time and his teleportation abilities, but even these powers get in Manhattan's own way, and cause him to lose sight of the what’s important to his life and to humanity as a whole.

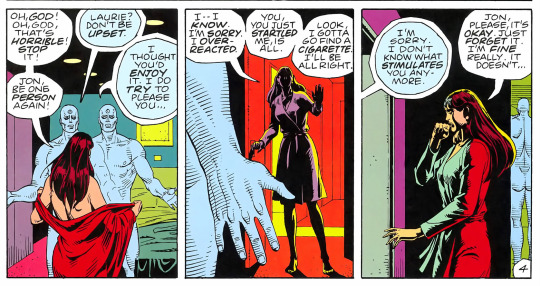

This is evident from the very introduction of the character of Dr. Manhattan in the first chapter, where he is boasted, before we even have a chance of seeing him, as the "indestructible man" by Rorscach. In his establishing panel, Manhattan is shown towering over Rorschach at the foreground of the image, yet in all his might and intimidation, he is distracted, tinkering with an unnamed piece of equipment in his lab, likely where he's been for quite some time prior to this introduction. This panel juxtaposes Manhattan's persona and image as a "God," with his cold detachment from humanity and subtly demonstrates how his God-like intellect, perception, and senses prevent him from seeing the importance of that which is happening right in front of him. Dr. Manhattan is, even in the immediate aftermath of a suspicious murder, a crisis, more concerned with the events occuring on a microscopic level, or dismantling, assessing, and reconstructing some futuristic piece of technology beyond any other character’s understanding; he won't even stop to heed his old friend's warning.

It is, in addition, no accident that the story ends with Jon teleporting Rorschach in response to Laurie's complaint that he is "upsetting" her. Manhattan's response to her comparatively minor annoyance is performing the miracle of teleporting Rorschach away, outside the facilities. This moment works to show Manhattan can do whatever he chooses, it shows that he is all powerful insofar as he can relocate people to his choosing, can shape-shift, and telekinetically dismantle machinery, but it's more a matter of what personally concerns him, what seems pressing by his own metrics. It should alarm us that Manhattan doesn't see the difference between a living and a dead body, and that he is yet so depended upon in this alternate American timeline.

Finally, an aspect of Dr. Manhattan’s origin (and character as whole) I find most curious is that in the process of “rebuilding” of himself, he had to have had some understanding of what components would be necessary for him to “come into being” again, but in this process he was somehow “unable” to reconfigure himself as fully human. His origin story reveals him as having always possessed a genius level intellect, however, emotionally he has always been absent and distanced. Even before his omniscience allegedly “soiled” his relationship to the material realm and to life itself, he never had a barometer for complex emotional interactions. During the time leading up to his transformation he was a 30 year-old man who was clearly not prepared to be apart of a serious relationship with Janey. He was still mentally absent from her needs as his significant other. Even in that moment of “intimacy” with Laurie, he is constantly trying and failing to please her. This allows us to imagine what would happen if “God” was there to answer every one of our prayers. It would still, as Watchmen notes, leave us unsatisfied, because there are no real satisfying answers, even for a god.

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rorschach: Identity and Humanity

Of all the things Moore’s Watchmen says about such broad topics as fascism, celebrity, and violence, I have always been most interested in what the graphic novel does not say, or rather, what it indirectly suggests through it’s impeccable characterization and imagery. On the surface, Watchmen, while not shy to less-than-subtle political critique, largely functions as a meta picture of comic books. It tackles the implications of overpowered God’s living among us, and more than anything, reveals that their presence would likely change things for the worst. And while undoubtedly portrayed as God’s by some stretched out meaning of the word, Moore’s cast of “hero’s” are often portrayed as more human than those without masks. What remains the story’s most impressive accomplishment is also one of the story’s most revealing in term’s of developing the character of Rorschach. I am of course referring to the chapter “Fearful Symmetry,” which is almost exactly, you guessed it, symmetrical, not only in it’s paneling and art, but in it’s themes, characterizations, and dialogue. It is nothing short of brilliant. Now while it isn’t until later on that the whole of Rorscach’s life story is unveiled, this chapter tells us a lot more about the character than one would expect. Most significantly, of course, is that we find out that the alter ego of Rorscach is a recurring “doomer” spotted in the background of countless iconic scenes. It’s this really powerful moment, where we find out that the “terror of the underworld” is a short, unstable loner. It re-contextualizes every scene this man was in, because we know who he becomes when story “isn’t” focused on him as a part of the background. What really draws me to this, besides the intricate details laced throughout the story that subtly point to Rorscach’s identity, is the events that unfold at the end of the comic. Rorscach is set-up to make it look as if he killed Jacobi, AKA, Moloc, a now retired supervillain. Rorscach, up until this point, is pretty impeccable in his investigation. He walks away from crime scenes and violent altercations with little regard for his safety, he isn’t afraid of asking “the big questions,” he is unrelentingly brutal in his techniques of interrogation, and he is putting together the pieces of a massive conspiracy pretty effectively, at least by comparison of his former coworkers, who all suspect Rorscach is behaving as per usual with his paranoia. Rorscach likes to think himself the only one who can spot what’s going on, behind all the corruption and lies of society, but that is his major flaw. His insular philosophical mindset doesn’t reflect the real world, and it often leads to him completely disregarding his allegedly unwavering sense of justice. The “hero,” of the story, the badass detective who talks in a gravelly voice and sees the world for what it is, he is incredibly unstable and consistently espouses reactionary ideas despite claiming he knows the truth, the only path forward for humanity. This man bent on bringing justice to the world, cannot seem to stand humanity at all, and thinks them as inherently vile creatures. He has “lived in the shadows,” his whole life, and from his own perspective, has been surrounded by the dark side of humanity so much so, that he projects his worldview onto his “objective” image of the world, and humans as a whole. His truth is linked to his desire of getting people to stop behaving “filthily” and it’s pretty clear this is driven by bias and personal experiences, that later get touched on. But it is this sort of twisting of the notion of protagonist that I want to focus on here. If the term “superhero” is at once linked with the idea of a “God” and “humanity,” in Moore’s world, this last page of the chapter is what tells us that. After feeling like he is getting closer to uncovering the details of the Comedian’s murder, Rorschach walks right into a trap. The second he realizes his misstep, we see his inner monologue shift. He isn’t so certain anymore, and he immediately defaults to insulting his own intellect andcgetting angry at himself not being careful enough. For the duration of the police raid, his image as an unstoppable force is torn to shreds. This is shown with really careful jutaposition. First, Rorschach does, to his credit, hold his own initially. He is more skilled using makeshift weaponry than the majority of heavil-armed police squad sent to place him under arrest. He makes a flamethrower out of a can of hairspray, literally materializing things that were not there before, as a literal God would. He takes down the police one by one, and has the advantage over them as he lurks in the shadows, until he needs to escape.

After plunging two or three stories to the street in an attempt to escape Jacobi’s apartment building, Rorschach shows his first signs of vulnerability. His image as a “god” is challenged. He refuses to believe that he, the objectivist, the only true form of justice in an unjust world, is in pain. He is so enraged by his failure to spot the set-up, that during a time he should be recovering from his injury, he is retroactively tracing his missteps. His ego is getting in the way, and this is clearly a human issue. God’s are allegedly perfect, but Rorschach, like everyone else, sometimes doesn’t see what’s right in front of him. And unlike a god, Rorshach is not impervious to fall damage. The police are as surprised by his human shortcomings as he is; they too expected the image of Rorshach to live up to his mythos.

The next section of panels shows Rorschach’s iconic mask, which is also key here; when an officer kicks it, the shifting black ink, which always moves in a symmetrical pattern, sort of scatters, and upon this disruption, it no longer looks perfectly symmetrical, which is of course to say, Rorschach is no longer maintaining the image of fear that he is known for, he is broken. And while the focus of my post here is not the “underlying queerness” of Rorschach’s character (a claim which I think is pretty well substantiated), I cannot help but pay attention to the fact that this raid on Rorschach is essentially a “queer beating.” There is a sense of gratification from the officers beating him, as if they’re getting more out of stopping the masked vigilante than merely putting an end to his career.

Finally, the officers remark about Rorschach’s height, his smell, and his overall un-recognizability. These things are not noticeable, though, on their own, but only in direct contrast to the methods by which Rorschach covers them up. These cops point out the smell, because it is the covering up of a smell that draws their attention. Similarly, they point out that he is a “runt,” not because they see him as short, but because they see him covering his height up with the lift’s he is wearing. The cops would likely not have pointed out that Rorschach was a nobody underneath his mask, if his reputation as the “terror of the underworld” didn’t surpass the reality of his identity. It is in the “covering up” of his humanity, that Rorschach fail’s to become anything more than human. His attempt to surpass humanity, as this objective specter who just lingers in the background, spectating and pontificating on the state of humanity, is largely revealed to be a farce. And it is no accident that Rorschach see’s it the other way around; he believes that Walter is his alter-ego and that the mask he wears is his true face.

113 notes

·

View notes

Photo

1.) First Roll (one roll with a 4-sided die): 1

Second Roll (one roll with a 25-sided die): 16

Third Roll (one roll with a 5-sided die): 3 (this will correspond with a passage from "Wilde_Scripts_Maintext.”)

2.) Blank Comic Observations: Tonal Pivot - Without dialogue, the robot’s intentions with his interaction with the dog character feels cynical from the beginning. The robot character gives away his intentions when he leans in to the dog character and you know his night will be ruined.

3.) The title, “From the point of view of feeling, the actor’s craft is the type,” still confuses me, especially with the context of the image. I don’t really know what it means by the craft being the “type.” If it means the type of feeling, then I would say it means acting is an extension of an actors emotions or feelings.

4.) I was unable to add the text to the comic but by transmitting the dialogue through text:

Title: From the point of view of feeling, the actor’s craft is the type

Panel 1: “Not send it anywhere?

2: My dear fellow, why?

3: Have you any reason?

4: What odd chaps you painters are!

5: You do anything in the world to gain a reputation

6: As soon as you have one,

7: you seem to want to throw it away.

8: It is silly of you,

9: for there is only one thing in the world worse than being talked about,

10: and that is not being talked about.

11: A portrait like this would set you far above all the young men in England, and make the old men quite jealous, if old men are ever capable of any emotion.”

5.) The context of the comic, which shows a robot who looks to be almost buzzing in the ear of the dog character, really highlights the kinds of attitudes and temperaments of the art community and it also makes it seem like Lord Henry was really most likely a nuisance to Basil in this moment, speaking from the perspective of expertise on a piece of art that was not even his. HE rains on Basil’s parade, much like the blank comic suggests on its own and the arc of the original comic.

1 note

·

View note

Text

This picture is one of the final shots of The Truman Show directed by Peter Weir (1998). The film stars Jim Carrey who portrays Truman Burbank, the unknowing star of a hit reality TV show from which the film’s title draws it’s name. From his birth, Truman has been participating in a television phenomeno unlike any other, one which follows his every move and thought. Truman’s whole life has been elaborately constructed by a film crew; his friends, his family, his best and worst memories have all been simulations. The plot of the Truman Show is largely concerned with how Truman’s whole life begins to unravel before his very eyes, each major set piece in the film serves as a ripple, a disruption in the world as Truman knows it. In many way’s Truman’s life has been simple, and comfortable; but that fabricated security feels, naturally, dishonest and disruptive to growth. Once Truman begins to understand that so much of what he has earned and lost has been preordained by a script advisor, his life gets complicated, and the fight to uncover the truth reveals itself to be a much more daunting task than Truman’s initial curiosity would have suggested. But here, at this moment where Truman discovers the border of the fictional world he’s grown up in, the complicated reality of the world away from Truman’s own clearly reveals itself; the line between reality and reality television is as clear as day. Nothing the cast and crew sets up to deter Truman from breaking free of his chains is effective, Truman always overcomes. This reveals that the architects of Truman’s life were never in command to begin with; if Truman is destined for anything, it’s the freedom to command his own vessel.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

The data gathered by Voyant really shows that there is a firm concept of experience in this poem. IT is necessary to fully engage in senses, in locations, in space, and in time.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

The “Is this a pigeon” meme format is versatile, tastefully mocking, and subversive. Love is a strong emotion for Whitman to have for perfume. The language avoids describing the scent of the perfume and even says it’s odorless It shows that his emotions are located in the images (it pictures) and nostalgia that are produced by the “sensation” and “taste” of the perfume.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Not only is the Google Maps layout more thorough and accurate, but it also is not marked by my personal memories. Much of what I located on my map were places special to me, so they were prioritized. These maps leave out the many friends houses I spent much of my time at, or the off-road trails me and my friends used to wander in our spare time. This definitely shows that I’m sentimental about where I grew up, and much of the nostalgia is mapped out is in fact a result of me recognizing I can only highlight the places, not the memories.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

“The Landscape.” Oswego, New York. 2020

The photographer draws our attention to their reinvention of the #horizon by redefining what pieces can be accurately referred to as #landscape photos. Their involvement in and relationship to each of the pieces is exemplified best in the images of the #collegecampus, where their #perspective is highlighted by the broadness of each shot.

2 notes

·

View notes