Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

The debate over jailing women for abortions

Rigorous intellectual consistency has not been a hallmark of Donald Trump’s career in public life, but on at least one notable occasion, he pursued an argument to its logical conclusion. Unsurprisingly, it turned out badly.

That was during the 2016 presidential campaign, when pressed by MSNBC’s Chris Matthews to elaborate on his ardent, if comparatively recent, opposition to abortion, he agreed that “there has to be some form of punishment” for women who have one.

Instantly, the guardians of conservative orthodoxy descended to inform him of his error: Women are actually the “victims” of abortion, as well as a much more numerous voting bloc than abortion providers, who are the real villains. Within hours, his campaign had issued a recantation. But the idea lived on, and even seems to be gaining support in some quarters of the antiabortion movement.

In fact, the idea of prosecuting women for abortions has been kicking around on the fringes of the antiabortion movement for some time. Back in 2014, conservative provocateur Kevin Williamson recommended (in a tweet and a podcast) execution, preferably by hanging, as the appropriate punishment. When those remarks surfaced last week, they cost Williamson, formerly with National Review, a plum job as a columnist for the Atlantic, whose editor found them “contrary to The Atlantic’s tradition of respectful, well-reasoned debate, and to the values of our workplace.”

Williamson’s fate fueled a spirited debate over the suppression of conservative views in the mainstream media that played out all up and down the Acela corridor. But meanwhile, far from the living rooms of Georgetown and Park Slope, an Idaho lawmaker and candidate for lieutenant governor, Republican Bob Nonini, endorsed legislation that would make abortion a capital crime, for both providers and the women who have the procedure. “There should be no abortion, and anyone who has an abortion should pay,” Nonini said at a candidate forum — before partially retracting, or at least obfuscating, his position, with the observation that “for practical reasons, as well as for reasons of compassion,” women as a rule haven’t been prosecuted, even in the years when abortion was illegal.

Idaho seems to be a hotbed of this kind of thinking; last year, another legislator, state Sen. Dan Foreman, introduced a bill to classify abortion as first-degree murder, on the part of both the woman and the provider. Foreman’s bill, which did not advance, made an exception to save the mother’s life, a compromise that some Republicans in the Ohio legislature obviously consider a sign of weakness: They are backing a bill to prosecute women who obtain an abortion even to save their own lives.

Politically, a platform of arresting women for homicide — there were around 20,000 abortions in Ohio in 2016 — could easily backfire on the GOP if executions were to start. As a legal strategy, it is part of the antiabortion movement’s broader effort to find a case that can give the Supreme Court an excuse to revisit, and hopefully overturn, its ruling in Roe v. Wade. But as a matter of principle, Williamson is far from alone in believing that women who seek an abortion are just as culpable as the physicians who perform the procedure. In fact, it is the only logical position to hold, in light of the movement’s endlessly repeated mantra that abortion is murder: Treat her as you would a woman who pays a hit man to kill her husband.

That was just the point Justice Blackmun made in his opinion in Roe, writing (in a footnote): “When Texas urges that a fetus is entitled to Fourteenth Amendment protection as a person, it faces a dilemma. … If the fetus is a person, why is the woman not a principal or an accomplice? Further, the penalty for criminal abortion … is significantly less than the maximum penalty for murder. If the fetus is a person, may the penalties be different?”

Maintaining that precise distinction has been the work of the mainstream antiabortion movement ever since. In response to Foreman’s bill, the Idaho chapter of Right to Life hurried to reassure the public that it “does not support any legislative action that would subject women to criminal penalties for an abortion.

“[W]e are convinced that abortion is most often a tragically desperate act,” the statement continued. “Available research indicates that coercion is often a factor in over 64% of the cases when women experience abortion. Despite rhetoric from advocates of abortion on demand, abortion is most often NOT freely chosen by women.”

Even taking this at face value, that leaves more than a third of women who did freely choose abortion. Should they get off scot-free? You could, if that’s your concern, pass a law making abortion a crime and specifically allow coercion as a defense. All in favor, say aye.

A different group, Abolish Abortion Idaho, which supported Foreman’s bill to criminalize abortion, has a more straightforward take on it: “[P]ro-life organizations like Right to Life of Idaho have never understood that they undermine their position by treating abortion as something less than what it is — murder. … The actual historical pro-life position, in contradiction to Right to Life of Idaho’s claim, is found in one of the oldest and most well supported documents on the planet, the Bible. In Genesis 9:6, we find this:

“‘Whoso sheddeth man’s blood, by man shall his blood be shed: for in the image of God made he man.’”

Well, that’s clear enough. As Nonini, the Idaho candidate for lieutenant governor, claimed, “In the history of the United States, long before Roe was foisted upon this country, no woman has ever been prosecuted for undergoing abortion.” That happens not to be true: It has happened many times, as a rule when women attempt to self-induce abortions, typically because they can’t find or afford a clinic to perform the procedure. And it is happening right now in a number of other countries, including El Salvador, where a woman was recently freed from prison after serving nearly 11 years for an abortion. The judges decided that, as she’d said all along, she had actually suffered a miscarriage.

Luckily for her, she wasn’t hanged. But some people would like to see that changed.

_____

Read more from Yahoo News:

Ken Starr: Justice Department should evaluate claims by Stormy Daniels

Advocates fear ICE is targeting immigrants who speak out

Trump isn’t the first president to politicize the census

While others march, these teens shoot. At targets.

Photos: Chappaquiddick: A tragedy that changed the course of American history

#_author:Jerry Adler#_uuid:cbcfccea-bb33-3e4e-860b-d060fb6c4e50#_revsp:Yahoo! News#_lmsid:a077000000CFoGyAAL#_draft:true

0 notes

Text

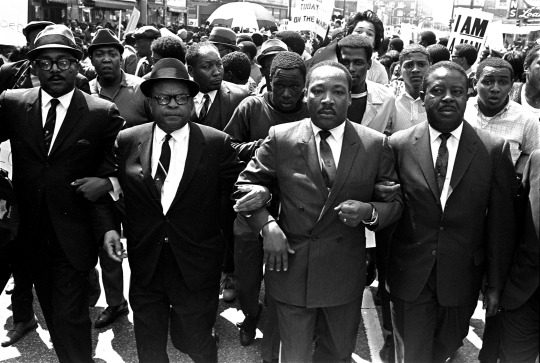

The view from the mountaintop: Martin Luther King’s turbulent, tragic last year

yahoo

Fifty years ago, on April 4, 1968, Martin Luther King Jr., who preached nonviolent resistance to oppression and war, was shot to death in Memphis. He was 39 years old. He left behind a wife and three children and a nation still riven by the divisions he had devoted his life to healing. Yahoo News takes a look back at his life and his legacy in this special report. Jonathan Darman assesses King as a man not without flaws, but with a passion for justice and a conviction that grace can still be found here among us sinners on earth. Senior Editor Jerry Adler looks back on the fateful last year of King’s life, beginning with his electrifying, and controversial, Riverside Church address against the war in Vietnam. National Correspondent Holly Bailey goes back to Selma, Ala., whose poverty moved King to increasingly turn his focus to economic justice, and finds not much has changed in the years since. Reporter Michael Walsh looks at how King almost died in an attack a decade earlier, and how the knowledge of his mortality shaped his ministry and message.

On April 4, 1967, a Tuesday, Martin Luther King Jr. took the pulpit at New York’s Riverside Church, the great Gothic cathedral conceived by John D. Rockefeller Jr., to deliver a speech entitled “Beyond Vietnam: A Time to Break Silence.” It announced a decisive shift in King’s message and ministry, from desegregation to a broader engagement with pacifism and social and economic justice. And it marked the beginning of the final year of his life. Exactly one year later, the concerns he spoke to that day would lead him to support a strike by sanitation workers in Memphis, Tenn., where he was shot and killed.

Martin Luther King Jr. delivers his ‘Beyond Vietnam’ speech at Riverside Church in New York City on April 4, 1967. (Photo: John C. Goodwin/UMC).

“I come to this great magnificent house of worship tonight because my conscience leaves me no other choice,” he said at the beginning of his talk, before a crowd of more than 3,000 that filled the immense church. “A time comes when silence is betrayal. That time has come for us in relation to Vietnam.” He went on to describe how Great Society antipoverty programs, “the real promise of hope for the poor, both black and white,” had been left “broken and eviscerated” by the costs and the social divisions imposed by the war. “We [are] taking the black young men who had been crippled by our society and sending them eight thousand miles away to guarantee liberties in Southeast Asia which they had not found in southwest Georgia and East Harlem. … We have been repeatedly faced with the cruel irony of watching Negro and white boys on TV screens as they kill and die together for a nation that has been unable to seat them together in the same schools.” He invoked his ministry, “in obedience to the one who loved his enemies so fully that he died for them.” And in his summation, he quoted from one of his favorite hymns, written more than 120 years before by the abolitionist James Russell Lowell:

Once to every man and nation comes the moment to decide

In the strife of Truth with Falsehood, for the good or evil side

Opposition to the war was not a new position for King, although it may have been news to some of his followers. Two years before, he had expressed his view that military action in Vietnam was “accomplishing nothing,” but that came in a question-and-answer session after a speech, and it attracted little attention. As the war escalated through 1965, the board of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference authorized him to pursue his own peace initiatives, drawing a warning from an assistant secretary of labor, George Weaver, described by the New York Times as “one of the highest-ranking Negroes in the Johnson administration,” that he risked provoking a “miscalculation” by the North Vietnamese or their patrons in the Soviet Union or China.

TIMELINE: Martin Luther King Jr.’s final year >>>

So he understood the risk he was taking. He would be breaking decisively with Lyndon Johnson, the president who had done more than any other since Lincoln to advance civil rights. He was being challenged on the left by a new generation of Black Power advocates and harassed by J. Edgar Hoover, whose covert efforts to discredit and destroy King would get new ammunition from his association with the people derisively called “peaceniks.” Peace activists were often labeled “Commies” in those years, and it was King’s long association with the left-wing activist Stanley Levison, whom Hoover suspected of being a Soviet agent, that brought King under FBI surveillance in the first place. Ironically, as the historian Taylor Branch points out, Levison was actually opposed to King’s involvement in antiwar causes and tried to talk him out of giving his Vietnam speech. (“I lost,” Levison told associates, in a wiretapped phone call, “and we’ll just have to live with the consequences.”)

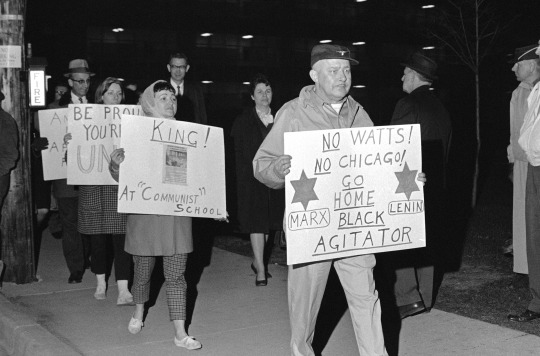

Protesters in front of the University of Wisconsin, April 28, 1967, where Martin Luther King was speaking. (Photo: AP)

But King was being pushed in the other direction by another influential aide, James Bevel, a fiery preacher from Mississippi, who saw the Vietnam War as an extension of America’s oppression of nonwhites. (Ironically, after King’s death, Bevel would become a supporter of Ronald Reagan and later drift to the fringes of politics as the running mate of perennial presidential candidate Lyndon LaRouche.) And King was pushed, more than anything else, by the logic of his own commitment to nonviolence. How, he wondered, could he demand that his own people brave police clubs and dogs without striking back, and not denounce the bombs the United States was dropping on children on the other side of the world? “It has been my consistent belief and position that non-violence is the only true solution to the social problems of the world and of this country,” King wrote a supporter just before the Riverside speech. “The principle of love which has motivated so many to strike out against the evils of racism here in America must motivate us to protest the brutal destruction of the Vietnamese People.”

In the spring of 1967, King, notwithstanding his 1964 Nobel Prize, was not quite the towering figure we look back on today. The great victories he had helped win — the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Voting Rights Act of 1965 — were receding into the (recent) past. The SCLC was in disarray and debt. King’s effort to tackle racial segregation in the North was foundering on the discovery that housing was a much more complicated and nuanced issue than whites-only lunch counters. King’s antiwar activism, while popular among the antiwar left, wasn’t winning many converts even among his allies in the civil rights movement, some of whom supported the war on principle, while others worried it would dilute his message about race. Within days of King’s speech the leading mainline civil rights group, the NAACP, disassociated itself from his stance, with a declaration that “we are not a peace organization nor a foreign policy association. We are a civil rights organization.” An editorial in the New York Times on April 7 (“Dr. King’s Error”) chastised King, in measured Times-speak, for making “too facile a connection between the speeding up of the war in Vietnam and the slowing down of the war against poverty.”

King’s life was already hectic and was about to get more so. He spent his last year crisscrossing the country in a whirl of speeches, sermons, meetings, rallies and marches. David Halberstam, who profiled him in the summer of 1967 for Harper’s magazine, noted that “most of King’s life is spent going to airports, and it is the only time to talk to him.” The period has been chronicled in a number of places, notably including the final volume of Branch’s magisterial trilogy on King’s life, “At Canaan’s Edge,” and a new HBO documentary, “King in the Wilderness.” Local newspapers reported on his visits whenever he touched down, in articles that make for arresting reading 50 years later, with their casual references to “Reds” and “Negroes,” which is the word King himself used. (It would be another year before the Amsterdam News, Harlem’s leading publication, totally banished the term in favor of “blacks.”) A partial list of the places King visited during that year includes, besides New York and his home in Atlanta: Boston; Los Angeles; San Francisco; Chicago; Cleveland; Philadelphia; Washington, D.C.; Miami; Grinnell, Iowa; Clarksdale, Marks and nearby towns in Mississippi; Geneva, Switzerland (for a world peace conference); Newcastle upon Tyne, England (to receive an honorary degree); Acapulco (for a two-day vacation); and, of course, Memphis. Along the way he rebuffed appeals to run for president as a peace candidate, served a five-day sentence in the Birmingham, Ala., jail, was accused by Hoover, in a secret report to Johnson, of plotting to blow up the Chicago Loop, and was bequeathed the entire estate — amounting to less than $10,000 — of the New Yorker writer Dorothy Parker, who admired him although they had never met.

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., leader of the Vietnam war protest demonstration which attracted 125,000 voices a repeated demand to “Stop the bombing” in New York, April 15, 1967. (Photo: AP)

A few days after the Riverside speech, King flew to California for a series of speeches. He held a press conference in part to deal with the repercussions of the address, at which he clarified, apparently for the benefit of donors to the SCLC, that he was not seeking to merge the civil rights and peace movements — meaning their contributions wouldn’t go to support his antiwar activism. By April 15 he was back in New York for a large and unruly march and rally for peace at the United Nations, alongside the antiwar activists Harry Belafonte and Benjamin Spock. “Many Draft Cards Burned — Eggs Tossed at Parade” was part of the headline in the next day’s Times. Citing some of the banners, signs and chants, the story introduced readers of the Times to a new slogan: “No Vietnamese ever called me nigger.”

Over the next few months King made repeated trips to Cleveland, one of four cities he had designated as a focus of his campaign to improve housing and job opportunities for blacks. He denounced the city’s crackdown in response to the previous summer’s riots, telling reporters, “a get-tough policy should mean getting tough against poverty, inferior education and rat-infested slums.” Meeting with local ministers and civil rights leaders, he involved himself in the details of local organizing: rent strikes, voter registration drives and “Operation Breadbasket,” targeted boycotts meant to force businesses to hire more black workers. “We’re not begging for freedom any more,” he told a press conference in May. Among a handful of reports on King’s local activities published by the Plain Dealer that summer and fall was a front-page picture of him relaxing on the lawn of a local activist, dressed, as he almost invariably was in photographs from those years, in a dark suit, white shirt and necktie. He was tossing a football to a couple of youngsters, including his sons, Martin III and Dexter, who were along for the trip.

On June 12, the Supreme Court upheld the conviction of eight black African-American ministers, including King and his brother, for contempt of court, stemming from a demonstration in Birmingham four years earlier. Bull Connor, Birmingham’s commissioner of public safety, had denied the group a permit to march, but they did anyway, invoking the doctrine of civil disobedience to illegitimate authority. In a 5-4 decision, with Chief Justice Earl Warren among the dissenters, the Court overruled that defense and ordered the men to serve their sentences and pay a $50 fine. Even if forbidding the march was unconstitutional, the decision held, the proper remedy was to appeal the denial to the courts. A few months later, one of the justices in the majority, Tom Clark, was replaced by Thurgood Marshall. Marshall, a civil rights hero in his own right, became the first African-American on the court, and, it’s safe to say, would have tipped the balance to the other side.

King was in and out of Cleveland and Chicago at least a half-dozen times that summer. In August he returned to Atlanta for the SCLC convention, where he announced plans to “dislocate” Northern cities with a campaign of “mass civil disobedience.” In a long speech titled “Where Do We Go From Here?” he enumerated achievements in Chicago and Cleveland, including the hiring of more black contractors by major department stores and taking out advertisements in Negro newspapers. The speech was well received, and the audience broke into applause and affirmation as King moved into his peroration with one of his signature aphorisms: “Let us realize that the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.” But reading it today one is struck by the realization that just a few years earlier King had been awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for his work to overturn a century of injustice and oppression and had stood in the Oval Office as Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act into law. A gap had opened between King’s soaring rhetoric and the grindingly slow process of bringing concrete improvements to the lives of millions of people in big-city ghettoes and the ramshackle towns of the Old South. The arc of the moral universe would have to be very long indeed if its course were to be measured by the hiring of more “Negro insect and rodent exterminators, as well as janitorial services” by chain stores in Chicago’s South Side.

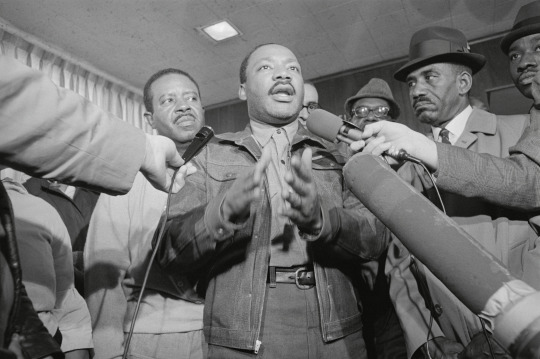

Rev. Ralph Abernathy (left) and Dr. Martin Luther King (center) are greeted with microphones as they emerge from the Jefferson County jail in Birmingham, Alabama on November 6, 1967. (Photo: Bettmann/Getty Images)

At the end of October, King and three others, including his brother, the Rev. A.D. King, surrendered in Birmingham to serve their sentences. “As we leave for a Birmingham jail today,” King said, “we call out to America: Take heed. Do not allow the Bill of Rights to become a prisoner of war.” He did not follow up on plans to write a sequel to his famous “Letter From Birmingham Jail” of 1963, although he did compose an essay, “A Bill of Rights for the Disadvantaged,” that was later published in the New York Times. The men were released after four days; King’s close aide Rev. Ralph Abernathy joked that since the lawyers had failed to keep the pastors out of jail, he was going back on his promise to keep them out of Hell. On being released, King announced plans to visit the Soviet Union. This was a trip he never made.

TIMELINE: Martin Luther King Jr.’s final year >>>

Now things began speeding up. On Dec. 4 King announced plans for a “poor peoples’ campaign for jobs or income,” which would take the form of a march on Washington the following spring. “In a news conference here,” the Times reported from Atlanta, “the winner of the Nobel Prize for Peace acknowledged that the ugly mood of many Negroes in the nation’s slums made the campaign ‘risky,’ but he asserted that ‘not to act represents moral irresponsibility.’” The reporter observed that “the Negro leader’s mood seemed deeply pessimistic.” A whirlwind of fundraising and planning for the march ensued, interrupted by more speeches and rallies. In January, he visited Joan Baez in jail in Oakland, Calif., where she was serving a sentence for staging a sit-in to protest the draft. On the men’s wing, he visited another peace activist, Ira Sandperl. Sandperl was struck, Branch writes, by the “contrast between the well-tailored figure in starched cuffs and the face of weary depression. King asked a favor. ‘When I’m in jail in Washington,’ he said, ‘come visit me there.’”

On Feb. 4, King was back in Atlanta in the pulpit of his home church, Ebenezer Baptist, where he preached what has become known as the “Drum Major” sermon, musing on the all-too-human desire for recognition. The text is from the 10th chapter of Mark, in which the apostles James and John request the honor of sitting alongside Jesus. This impulse is the root of the social evil of racism, King said, “a need some people have … to feel that their white skin ordained them to be first,” and also of the personal vices of jealousy, arrogance and pride. That thought in turn led him to consider his own place in history and how he would want to be remembered and eulogized. “I don’t want a long funeral,” he said. “Tell them not to talk too long. Tell them not to mention that I have a Nobel Peace Prize — that isn’t important.” He wanted to be remembered, he said, as someone who served others, who tried to feed the hungry and serve humanity and who “tried to be right on the war question.” “Yes, Jesus,” he concluded, “I want to be on your right or your left side, not for any selfish reason. … I just want to be there in love and in justice and in truth and in commitment to others, so that we can make of this old world a new world.”

It was also in February that King appeared as a guest on The Tonight Show, where Belafonte, a close friend, was filling in as host. King mentioned he had flown up from Washington on a plane that had been delayed by “mechanical difficulties,” and he was glad to land safely. “I don’t want you to think that as a Baptist preacher, I don’t have confidence in God in the air,” he said. “It’s just that I’ve had more experience with him on the ground.”

“Do you fear for your life?” Belafonte asked.

“Not really,” King replied. “Ultimately it isn’t important how long you live — it’s how well you live.” He was 39.

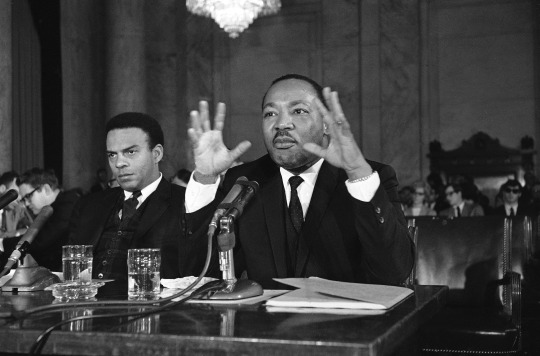

Martin Luther King, Jr., says he is confident he will get strong support his plan to raise an army of the poor to camp outside the Capitol, March 2, 1968. The “poor peoples’ campaign” is demanding action by Congress to provide jobs or income for the poor. At left is the Rev. Andrew Young, executive Vice President of the Southern Conference. (Photo: AP)

On March 3 he returned to Ebenezer to preach on “Unfulfilled Dreams,” about world-historical figures who never achieved their greatest goals — like Gandhi, who lived just long enough to see his dream of a united India shattered by religious war and partition, or King David, who died before he could build a temple to the Lord. Each of us is building our own temple, King told the worshippers. We are all traveling to a destination, and what matters isn’t whether we reach our destination, but that we are on the right road.

He was hurtling toward his own destiny, and perhaps he sensed it. Certainly those around him did. His aides worried he was pushing himself too hard, in danger of burning out, or of losing control of the civil rights movement as more militant figures rose to prominence, mocking his lifelong commitment to nonviolence. He spoke in Detroit in mid-March, then flew to Los Angeles for speeches and meetings where, Branch writes, he let himself be talked into committing to visit “Indian reservations and migrant labor camps from California to Appalachia and Massachusetts” in the run-up to the Poor People’s March, whose start was barely more than a month away. Then he took a call from James Lawson, a preacher and organizer in Memphis, urging him to speak at a rally in support of a strike by the overwhelmingly black sanitation workers’ union. So he flew into Memphis by way of New Orleans on March 18, arriving to a packed auditorium at the Mason Temple to deliver a rousing address.

“We are tired of being at the bottom! We are tired of our men being emasculated so that our wives and daughters have to go out and work in the white lady’s kitchen,” he thundered. As the cheers filled the packed hall, he promised that he would be back.

The Rev. Ralph Abernathy, right, and Bishop Julian Smith, left, flank Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., during a civil rights march in Memphis, Tenn., March 28, 1968. (Photo: Jack Thornell/AP)

From Memphis, King descended into the Delta, visiting towns in some of the poorest counties in the United States, speaking in what the Times called “a shabby firetrap of a building whose interior walls are covered with funeral-parlor calendars” showing a suffering — white-skinned — Jesus on the cross. “I am very deeply touched,” King told mothers who couldn’t afford shoes for their children. “God does not want you to live like you are living.”

Then he got back on an airplane to meet with supporters in New York, visiting a Harlem tenement where a local activist, Mrs. Bennie Fowler, cooked him lunch and served it beneath a clothesline strung across her dining room. He apologized for canceling some appearances, explaining “I’ve been getting two hours’ sleep a night for the last 10 days.”

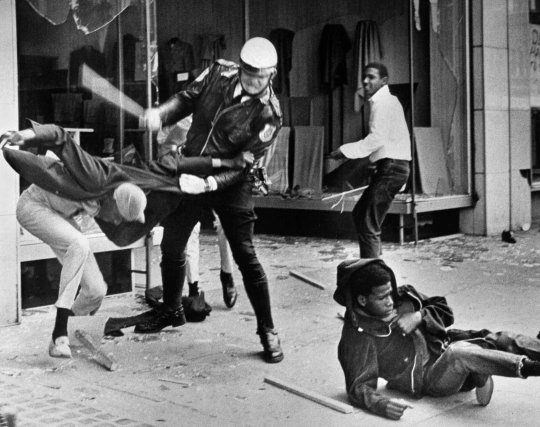

Then he returned to Memphis for a march that started late and quickly turned ugly, with looting, cops injured and shooting back and hundreds arrested. King back in his hotel room was overcome with remorse (according to FBI transcripts of his wiretapped phone conversations), blaming himself for being unable to rein in the anger he had always hoped to keep from spilling over into violence.

“Maybe we just have to admit that the day of violence is here,” he said in despair to his aides. “And maybe we have to give up and let violence take its course.” Then he flew home to Atlanta.

A police officer uses his nightstick on a youth reportedly involved in the looting that followed the breakup of a march led by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. March 28, 1968, in Memphis, Tenn. (Photo: Jack Thornell/AP)

Newspapers around the country denounced King as an agitator and troublemaker, following, in some cases, scripts that had been surreptitiously provided by Hoover’s agents. King flew to Washington to preach a Sunday service at the National Cathedral, describing the poverty and misery he had seen the week before in Mississippi. That day, Sunday, March 31, ended with Johnson’s speech announcing he would not run for another term as president in November.

And then King returned to Memphis for a third time. His aide Xernona Clayton had picked him up at his home, where, she recounts in “King in the Wilderness,” his two sons had uncharacteristically tried to keep him from leaving. “He said, what in the world happened to these kids. They must be trying to tell me they’re missing me more, and when I come back I’ve got to change my habits.”

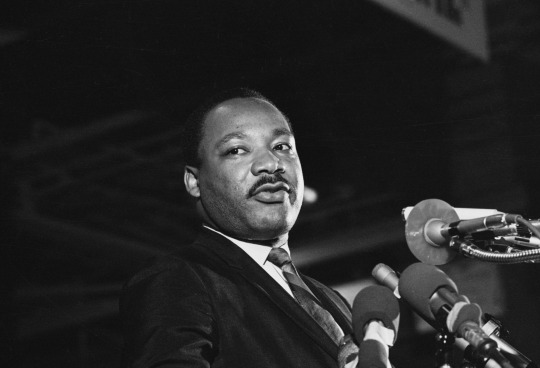

His flight out of Atlanta was delayed because of bomb threats, and he arrived at the Mason Temple amid a Biblical-magnitude thunderstorm. He spoke about the strike and Operation Breadbasket, and he repeated his warnings about violence: “We don’t have to argue with anybody. We don’t have to curse and go around acting bad with our words. We don’t need any bricks and bottles; we don’t need any Molotov cocktails.” He recalled the time he had been stabbed at a book signing in New York, an attempted assassination that came very close to succeeding. Doctors told him just a sneeze could have ruptured his aorta, and then “I wouldn’t have had a chance later that year, in August, to try to tell America about a dream that I had had,” and “I wouldn’t have been down in Selma, Alabama, to see the great movement there.”

“And then I got into Memphis,” King continued. “And some began to say the threats, or talk about the threats that were out, or what would happen to me from some of our sick white brothers.

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. speaks to a mass rally on April 3, 1968 in Memphis, Tenn. (Photo: Bettmann/Getty Images)

“Well, I don’t know what will happen now; we’ve got some difficult days ahead. But it really doesn’t matter with me now, because I’ve been to the mountaintop. Like anybody, I would like to live a long life — longevity has its place. But I’m not concerned about that now. I just want to do God’s will. And He’s allowed me to go up to the mountain. And I’ve looked over, and I’ve seen the Promised Land.

“I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight that we, as a people, will get to the Promised Land. And so I’m happy tonight; I’m not worried about anything; I’m not fearing any man.”

And he ended with a line from the great Civil War anthem, the Battle Hymn of the Republic:

“Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord!”

That was the night of April 3, 1968.

yahoo

_____

#_author:Jerry Adler#_uuid:4022b2dd-cf51-3cc0-a008-04ed3a3353d1#_revsp:Yahoo! News#_lmsid:a077000000CFoGyAAL#The King Assassination – 50 years later

0 notes

Text

Elizabeth Warren, Cherokees and 'Pocahontas': Why it matters

Pocahontas, 1595-1617, and Sen. Elizabeth Warren, D-Mass. (Photos: Getty Images, Bill Clark/CQ Roll Call)

By now, most Americans have heard that Elizabeth Warren, the Massachusetts senator, scourge of Wall St. and liberal hero, falsely claimed to have French ancestry, leading President Trump to mock her as “Joan of Arc.”

Wait, that’s not right.

It was Native American ancestry, specifically Cherokee, that Warren claimed, and the nickname Trump bestowed on her, in a dozen tweets and numerous speeches, was “Pocahontas.”

In principle, the situations should be equivalent. But they’re not. Being mistaken about a French great-grandmother would barely rise to the level of a presidential tweet, even from Trump. But laying claim to Indian blood is taken very seriously in the United States, which tells us not much about Warren, but a great deal about how Native and non-Native Americans view their shared history, four centuries after their first fateful encounters.

Let’s leave aside Trump’s boorishness in bullying Warren over this obscure peccadillo, his utter lack of decorum and decency in bringing it up at a ceremony honoring Native American veterans, and even the fact that Trump himself claimed Swedish descent on his father’s side, when in fact his grandfather was German. If he wants to call her Pocahontas, she should be able to call him Olaf.

We can stipulate — as Warren herself admits, although without quite retracting the original claim — that there is no evidence to support it. Her ancestry has been researched thoroughly, including by Twila Barnes, a freelance genealogist specializing in the Cherokee tribe. Since Warren’s first Senate run in 2012, Barnes has been debunking her claims in dozens of blog posts under headlines like “Indian or Pretendian?” The usual media fact-checking websites have weighed in, and concluded that Warren’s claim appears based on little, or nothing, more than family legend.

Warren has rejected calls to submit to a DNA test that could, in theory, shed light on her lineage. “I know who I am,” Warren said recently in an interview on NBC’s “Meet the Press.” “That’s the story that my brothers and I all learned from our mom and our dad, from our grandparents, from all of our aunts and uncles. It’s a part of me, and nobody’s going to take that part of me away.”

In fact, DNA is a blunt tool to determine Indian descent, especially going back more than four or five generations, by which time the genetic signature may be undetectable. Moreover, Indian ancestry is meaningful mostly insofar as it ties one to a specific tribe, but DNA tests don’t (yet) distinguish among tribes. The leading commercial DNA services generally treat “Native American” as a unitary category covering the entire Western Hemisphere. Indian tribes set their own criteria for membership, typically requiring a documented paper trail. DNA tests don’t qualify.

Warren never sought membership in the Cherokee tribe. Why would she? Politically, there wouldn’t have been much to gain even if she were a full-blood Cherokee; there are only around 350,000 enrolled Cherokees in the world, and not many of them live in Massachusetts. (Shiva Ayyadurai, the Mumbai-born tech entrepreneur who boasts of having invented email when he was in high school, is running against Warren for the Senate as the “real Indian” in the race.) Trump accused Warren of inventing an Indian background to gain an edge in her career. It’s true that in the 1990s, when she taught at Harvard Law School, the university cited her as a Native American to demonstrate the diversity of its faculty. This is information, or misinformation, that could only have come from Warren herself, who also, beginning in 1986, listed herself as a minority in a directory of law-school professors. But she was a recognized authority in her field when Harvard recruited her, and her heritage “simply played no role in the appointments process,” according to Charles Fried, who was Ronald Reagan’s solicitor general and sat on the law school committee that selected her. “Let me be clear,” Warren said in a campaign ad during her first Senate run. “I never asked for, never got any benefit because of my heritage.”

By contrast, when Trump claimed Swedish ancestry he was perpetuating a lie invented by his father for a very specific purpose. Trump’s biographers claim that Fred Trump, a New York City real estate developer, sought to hide his German background during and after World War II so as not to complicate his business relationships, especially with Jews.

And contrary to what some people seem to believe, tribal citizenship is not a quick way to get rich. A few, mostly small, tribes distribute casino profits to their members in impressive amounts, but on the whole Indians are the poorest ethnic group in the country, according to the Native American Rights Fund. The Cherokee Nation, by far the largest of the three bands comprising the Cherokee tribe, has a territory that covers 14 counties in northeastern Oklahoma. (Warren was born in Oklahoma City, which is outside the territory.) The tribe provides certain housing, health and educational benefits to members within those 14 counties, but Warren would have had to move there to take advantage of them. For the majority of Cherokees who live elsewhere, says Barnes, “the benefit is the acknowledgment of your ancestry, the kinship, the link to your history, your ancestors’ sacrifice.”

Of course, those are the same motivations that drive people to research ancestors from anywhere, including those who never moved more than 20 miles from Ellis Island after getting off the boat. But you don’t often hear about people inventing, or imagining, or repeating false family legends about, say, Russian ancestry, except for those trying to get their hands on the Romanov family’s crown jewels.

It’s different with Indians. The No. 1 question among clients of AncestryDNA is “where is my Native American ancestry,” according to genealogist Crista Cowan, who guesses that if all the Americans who claim to have Indian forebears were right, they would make up half the population. She mentions some of the ways such legends get started, including ancestors who happened to look Indian, or who lived in what was called “Indian territory” before it became the State of Oklahoma. In Cowan’s own family, the myth began with a photograph of a long-ago aunt dressed like an Indian; on investigation, it turned out to have been taken at a novelty booth in a fair. Barnes notes that over the years there have been promises, or actual payments, to compensate Cherokees for the seizure of their lands. This created an obvious incentive to apply to join the tribe. “People see records of those applications, they say, oh, great-grandpa wouldn’t have lied. But maybe he did.”

And the legends persist, because almost every American, whether or not he saw “Dances With Wolves,” wants to feel a kinship with Indians. “One of the top five genealogical myths is ‘My great-great-grandmother was a Cherokee princess,’” Barnes says. “There is no such thing.” Being able to claim Indian blood is a way of being rooted in the very soil of America, the stuff that lies beneath the grass of Trump’s golf courses. “Let’s face it, being part Native American is cool,” “Daily Show” host Trevor Noah remarked last fall, apropos of the Pocahontas controversy — “but just part, enough that you’re interesting at a party, not so much that they build a pipeline through your house.” In progressive circles, to claim Indian blood is a form of one-upmanship, a way to show you’ve pre-checked your white privilege. It inoculates you against the charge of being a colonizer. When Europeans are accused of stealing the Indians’ land, you can say, not me.

But, of course, Europeans did steal the Indians’ land, which may help explain why Cherokees like Barnes are so outraged by what otherwise might be excused as a harmless retelling of a family legend. (“Yep, I’m full-blooded Russian. Want to see my Cossack dance?”) It adds the insult of cultural theft to the injury of ethnic cleansing under the Indian Removal Act, which displaced Cherokees and other tribes from their homes in Georgia and Alabama on a journey remembered as the Trail of Tears. Rebecca Nagle, a Cherokee writer and activist, wrote a harsh takedown of Warren recently that was especially notable for where it appeared, on the left-leaning website Think Progress. She wrote, imagining the apology she would like to see from Warren: “I am deeply sorry to the Native American people who have been greatly harmed by my misappropriation of Cherokee identity. … Native Nations are not relics of the past, but active, contemporary, and distinct political groups who are still fighting for recognition and sovereignty within the United States. Those of us who claim false Native identity undermine this fight.”

Warren has been mentioned as a possible presidential candidate in 2020, although she recently announced she was not running. If she did run, Cherokee voters might face a difficult choice between the woman Republicans have been calling “Fauxcahontas,” and Donald Trump, who has adopted as his role model Andrew Jackson — the president who signed the Indian Removal Act.

Read more from Yahoo News:

GOP lawmaker knocks Trump for Putin call but refuses to distance himself from president

What’s behind Trump’s charges about Andrew McCabe’s wife?

On gender, candidates in the Trump era negotiate a changed landscape

Why aren’t Western sanctions stopping Putin?

Photos: Scenes from ‘March for Our Lives’ rallies from around the world

#Jerry Adler#_author:Jerry Adler#signals#_uuid:4f70c338-caeb-3945-8213-da6fc7b6e58a#_revsp:Yahoo! News#_lmsid:a077000000CFoGyAAL#_draft:true

0 notes

Text

Who’s getting under Trump’s skin today? Lawyers

John. Dowd, President Donald Trump’s lead lawyer in the Russia investigation, who has left the legal team. Dowd says he “loves the president” and wishes him well. (AP Photo/Richard Drew, File)

Lawyers were very much on Donald Trump’s mind early Sunday morning, as he fired off a couple of tweets ostensibly about his defense in the Russia probe, but with a clear subtext about the profession in general, stopping just short of calling them all crooks who intentionally run up their bills:

Many lawyers and top law firms want to represent me in the Russia case…don’t believe the Fake News narrative that it is hard to find a lawyer who wants to take this on. Fame & fortune will NEVER be turned down by a lawyer, though some are conflicted. Problem is that a new……

….lawyer or law firm will take months to get up to speed (if for no other reason than they can bill more), which is unfair to our great country – and I am very happy with my existing team. Besides, there was NO COLLUSION with Russia, except by Crooked Hillary and the Dems!

Trump’s defense team has been in turmoil recently, with the resignation of his lead lawyer, John Dowd and the hiring of Joseph diGenova, a frequent commentator on Fox News who has pushed the theory that the FBI is attempting to frame Trump in the investigation of his campaign’s relationship to Russian government agents.

Trump’s observation that “Fame & fortune will NEVER be turned down by a lawyer” seemed intended to rebut stories that he is having trouble hiring top-flight legal talent. Yahoo News reported that at least four top law firms turned down Trump as a client last year. The New York Times said on Thursday that the president “tried last summer to hire some of Washington’s top lawyers to represent him. But many shied away, aware of the president’s history of ignoring his lawyers’ advice and frequent failure to pay his legal bills.”

But his remark about legal bills was an obviously heartfelt complaint by someone who has paid more than his share of them over the years. The going rate for top-tier Washington and corporate lawyers was $2,000 an hour in 2016, and, yes, you do have to pay them for the time it takes to get “up to speed” on your case.

Obviously Trump is frustrated by the ongoing special counsel investigation, since he ends every tweet on the subject with the catchphrase NO COLLUSION. But it’s hard to avoid the suspicion that there was another legal matter on his mind, hours before 60 Minutes is expected to air its interview with the actress Stormy Daniels, who reportedly plans to discuss her affair with Trump and the efforts to silence her.

That is, according to her lawyer.

#_author:Jerry Adler#_revsp:Yahoo! News#_lmsid:a077000000CFoGyAAL#_uuid:917526f0-c124-3222-be1f-bb49e52b40e8

0 notes

Text

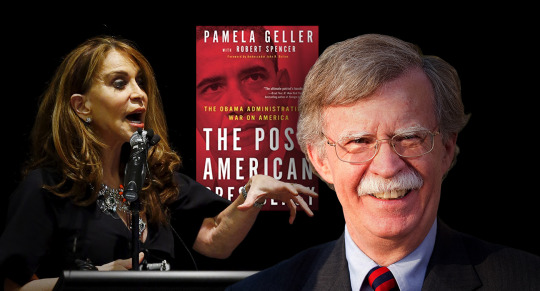

Bolton is a fan of Islamaphobe activist Pamela Geller

Activist and author Pamela Geller, and John Bolton. (Photo illustration: Yahoo News; photos: Mike Stone/Reuters, Amazon, Simon Dawson/Bloomberg via Getty Images)

As national security adviser, John Bolton will be responsible for advising President Trump on relations with the rest of the world, but especially America’s rivals and enemies — a category he defines broadly, including much of the Muslim world.

Within hours of the announcement that Bolton would be replacing Gen. H.R. McMaster in the West Wing, the Council on American-Islamic Relations was out with a fact sheet on his background, including his “cozy relationship with anti-Muslim hate groups.” It singled out in particular his relationship with Pamela Geller, the author and anti-Muslim activist described by the Southern Poverty Law Center as “probably the best known — and the most unhinged — anti-Muslim ideologue in the United States,” known for her efforts to post anti-Muslim ads on New York City buses and for speculating (in a blog post that’s no longer online) that Barack Obama was actually the illegitimate love child of Malcolm X.

Anders Breivik, the right-wing Norwegian terrorist who went on a shooting rampage at a youth camp in 2011, killing scores of youngsters, was a fan of Geller’s writings. In turn, she wrote that the victims were enrolled in an anti-Israel “indoctrination training center,” and would have grown up to become “future leaders of the party responsible for flooding Norway with Muslims who refuse to assimilate, who commit major violence against Norwegian natives including violent gang rapes, with impunity, and who live on the dole.”

(Earlier this year, Oath Inc., the parent company of Yahoo News, canceled a social-media show hosted by two of Geller’s daughters, who go by the surname of Geller’s late husband, Michael Oshry. After the daughters’ past inflammatory tweets emerged, Oath said in statement: “The Morning Breath, an Oath social media show, is being canceled immediately and we have launched an internal investigation and will take other appropriate steps based on the results of the investigation.”)

Geller is also a long-time fan of John Bolton, endorsing him for president in 2011 as “the antidote to the sick, debilitated state of the country which Obama has inflicted upon us.” And Bolton is a fan of hers. He wrote the forward to her 2010 book (with Robert Spencer, director of the anti-Muslim group “Jihad Watch”), “The Post-American Presidency: The Obama Administration’s War on America.” They wrote: “Barack Hussein Obama [Geller took pains to use Obama’s middle name whenever possible] hid the fact that he was a hard-line, doctrinaire socialist and statist, who believed in central planning and government control of the economy as fervently as Stalin or Mao or Kim Jong Il ever did.”

In his forward, Bolton denounced Obama for the sins of globalism, defeatism and weakness in pursuing the war on terror. This position left him with some explaining to do when Obama authorized the successful attack that killed Osama bin Laden, but Bolton was up to it, telling a Republican campaign event that “in 1969, when Americans landed on the moon, it is like Richard Nixon taking credit for that. It happened to occur during his presidency.”

In its statement, CAIR said “We urge Americans across the political spectrum to speak out against the appointment of John Bolton as White House National Security Adviser because of his ties to anti-Muslim bigots and his promotion of extremist views that will inevitably harm our nation and that could lead to unnecessary and counterproductive international conflicts.”

_____

Read more from Yahoo News:

GOP lawmaker knocks Trump for Putin call but refuses to distance himself from president

What’s behind Trump’s charges about Andrew McCabe’s wife?

On gender, candidates in the Trump era negotiate a changed landscape

Why aren’t Western sanctions stopping Putin?

Photos: Food insecurity raises death toll after Congo violence

#_author:Jerry Adler#_revsp:Yahoo! News#_lmsid:a077000000CFoGyAAL#_uuid:c89cff5f-76be-3c47-b0c2-e3fd265b55f6

0 notes

Text

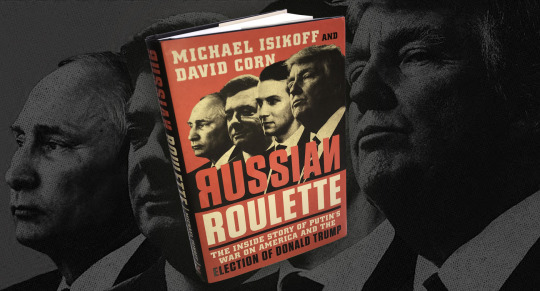

The cyberwar that never happened: How Obama backed down from a counterstrike against Russia

Photo-illustration: Yahoo News

In the summer of 2016, as evidence mounted of Russian meddling in the U.S. election, a team in the White House began work on a far-reaching counterstrike against Russian media, the Kremlin oligarchy, and Putin personally — plans that were shelved when President Obama’s national security adviser, Susan Rice, ordered the staffers to “stand down.”

The details of the project, and the debate within the administration of how aggressively to confront Moscow, are told in a new book, “Russian Roulette: The Inside Story of Putin’s War on America and the Election of Donald Trump,” by Michael Isikoff and David Corn, Washington bureau chief for Mother Jones.

Excerpts from the book are being published this week by Yahoo News and Mother Jones. The book goes on sale Tuesday, March 13.

The counteroffensive was the brainchild of Michael Daniel, the White House cybersecurity coordinator, and Celeste Wallander, the chief Russia expert in the National Security Council. One proposal was to unleash the NSA to mount its own series of far-reaching cyberattacks: to dismantle the Russian-created websites, Guccifer 2.0 and DCLeaks, that had been leaking the emails and memos stolen from Democratic targets; to bombard Russian news sites with a wave of automated traffic in a denial-of-service attack that would shut them down; and to launch an attack on the Russian intelligence agencies themselves, seeking to disrupt their command and control nodes.

“I wanted to send a signal that we would not tolerate disruptions to our electoral process,” Daniel told Isikoff and Corn. “The Russians are going to push as hard as they can until we start pushing back.”

Wallander proposed leaking snippets of classified intelligence to reveal the secret bank accounts in Latvia held for Putin’s daughters — a direct slap at the Russian president that would be sure to infuriate him. Working with Victoria Nuland, the assistant secretary of state for European affairs, Wallander drafted other proposals: to dump dirt on Russian websites about Putin’s money, about the girlfriends of top Russian officials, about corruption in Putin’s United Russia Party. The idea was to give Putin a taste of his own medicine. “We wanted to raise the cost in a manner Putin recognized,” Nuland says.

But the “signal” Daniel had intended was never sent; the plans were scrapped by Rice and Lisa Monaco, the president’s homeland security adviser, who worried that if news of the project leaked it would “box the president in” and create pressure for him to act. One day in late August, according to Isikoff and Corn, Rice called Daniel into her office and ordered him to “stand down” and “knock it off.” The White House was not prepared to endorse any of these ideas. “Don’t get ahead of us,” Rice warned.

Daniel walked back to his office. “That was one pissed-off national security adviser,” he told one of his aides.

Russian President Vladimir Putin, presidential candidates Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton, CIA director John Brennan, President Barack Obama and national security adviser Susan Rice. (Photo-illustration: Yahoo News; photos: AP (7), Getty Images)

At his morning staff meeting, Daniel matter-of-factly told his team to stop work on options to counter the Russian attack: “We’ve been told to stand down.” Daniel Prieto, one of Daniel’s top deputies, recalled being incredulous at the decision. As Prieto saw it, the president and his top aides didn’t get the stakes. “There was a disconnect between the urgency felt at the staff level” and the views of the president and his senior aides, Prieto later said. When senior officials argued that the issue could be revisited after Election Day, Daniel and his staff took strong exception. “No — the longer you wait, it diminishes your effectiveness. If you’re in a street fight, you have to hit back,” Prieto remarked.

The series of decisions — and nondecisions — made by Obama and his top aides in response to the Russian attack have been the subject of intense debate ever since. In “Russian Roulette,” Denis McDonough, Obama’s chief of staff, defends the president’s handling of the issue, saying Obama was concerned that escalating the conflict with the Russians could feed Trump’s narrative that the election was rigged. “The first-order objective directed by President Obama,” McDonough recalled, “was to protect the integrity of election.” Obama wanted to make sure whatever action was taken would not lead to a political crisis at home — and with Trump the president feared the possibility for that was great.

After the stand-down order, according to Isikoff and Corn, Obama and his senior advisers decided on a different approach — one that would frustrate the NSC hawks, who believed the president’s team was tying itself in knots and looking for reasons not to act. Rather than striking back, the president would privately warn Putin and vow overwhelming retaliation for any further intervention in the election. Obama delivered the threat at a private meeting with Putin on the sidelines of the G20 summit that September. The president later informed his aides he had delivered the message he and his advisers had crafted: We know what you’re doing. If you don’t cut it out, we will impose onerous and unprecedented penalties. One senior U.S. government official briefed on the meeting was told the president said to Putin in effect: “You f*** with us over the election and we’ll crash your economy.”

White House officials believed for a while that Obama’s warning had some impact: They saw no further evidence of Russia cyberintrusions into state election systems. But as they would later acknowledge, they largely missed Russia’s information warfare campaign aimed at influencing the election — the inflammatory Facebook ads and Twitter bots created by an army of Russian trolls working for the Internet Research Agency in St. Petersburg.

On Oct. 7, 2016, the Obama administration finally went public, releasing a statement from the Office of the Director of National Intelligence and the Department of Homeland Security that called out the Russians for their efforts to “interfere with the U.S. election process,” saying that “only Russia’s senior-most officials could have authorized these activities.” But for some in Hillary Clinton’s campaign and within the White House itself, it was too little, too late. Wallander, the NSC Russia specialist who had pushed for a more aggressive response, thought the Oct. 7 statement was largely irrelevant. “The Russians don’t care what we say,” she later noted. “They care what we do.” (The same day the statement came out, WikiLeaks began its month-long posting of tens of thousands of emails Russian hackers had stolen from John Podesta, the CEO of the Clinton campaign.)

Nearly two months after the election, Obama did impose sanctions on Moscow for its meddling in the election — shutting down two Russian facilities in the United States suspected of being used for intelligence operations and booting out 35 Russian diplomats and spies. The impact of these moves was questionable. Rice would come to believe it was reasonable to think that the administration should have gone further. As one senior official lamented, “Maybe we should have whacked them more.”

_____

Read more from Yahoo News:

Democrat reiterates doubts about Jared Kushner’s loyalty to the U.S.

A new generation of anti-gentrification radicals are on the march in Los Angeles — and around the country

In exile with Bill Kristol, the Republican resister-in-chief

Seven days in Trumpland: Confusion, scandals and indictments

Photos: Women march on International Women’s Day

#_author:Jerry Adler#_uuid:92ba25c3-98bd-3a5c-9a5e-1b42ca4ba782#_revsp:Yahoo! News#_lmsid:a077000000CFoGyAAL#_draft:true

0 notes

Text

Trump and the Russians: A new book describes how it all began — at a Las Vegas nightclub

Photo illustration: Yahoo News

The seeds of the relationships between Donald Trump and key figures in the Russian business and political worlds — now the subject of special counsel Robert Mueller’s investigation — were planted at least five months before Trump’s now famous 2013 trip to Moscow, during a previously unreported visit to a raunchy Las Vegas nightclub with the son of a prominent oligarch and Putin ally, according to a new book about Trump and his Russian ties. The book is excerpted today in Yahoo News and Mother Jones magazine.

The book also reveals a January 2015 meeting at Trump Tower between Trump and two key figures in the Russia probe — the oligarch’s son, pop singer Emin Agalarov, and his publicist, Rob Goldstone — during which the real estate mogul strongly hinted about his plans to run for president. Both Emin Agalarov and Goldstone have come under scrutiny because of their pivotal roles in setting up the notorious June 2016 meeting at Trump Tower by promising Trump campaign officials “high-level and sensitive” information from the Kremlin that would “incriminate” Hillary Clinton.

Some of the contacts and meetings among Trump, Russian billionaire Aras Agalarov, his son, Emin, and the British publicist Goldstone are detailed for the first time in the book, “Russian Roulette: The Inside Story of Putin’s War on America and the Election of Donald Trump,” by authors Michael Isikoff, the Chief Investigative Correspondent for Yahoo News; and David Corn, the Washington bureau chief for Mother Jones. The book will be released on Tuesday, March 13.

The excerpt being published today by Yahoo News and Mother Jones explores the events surrounding Trump’s November 2013 visit to Moscow to oversee the Miss Universe pageant, and to vigorously pursue his long-standing dream of building a Trump Tower in the Russian capital. A deal was reached for the project with Aras Agalarov, an oligarch known as “Putin’s builder,” with financing by a bank controlled by the Russian government.

That agreement, in turn, grew out of a June trip to Las Vegas, where Trump was presiding over the Miss USA pageant, a preliminary to Miss Universe. It has previously been reported that Trump dined with the Agalarovs, Goldstone and others at a Las Vegas restaurant while there. But as the book reveals, Trump later that night joined Emin Agalarov, Goldstone and the reigning Miss Universe, Olivia Culpo, for an after-party at a nightclub called the Act, known for shows, extreme even by Vegas standards, that simulated acts of sadomasochism and bestiality and one (called “Hot for Teacher”) in which female dancers pretended to be college students urinating on their professor. (The club, the book notes, laid in a supply of Diet Coke for the teetotaling Trump.) The club was the target of an undercover investigation by the Nevada Gaming Commission at the time of Trump’s visit, and many of its acts — including those involving simulated urination — were later banned by a Nevada state judge as “lewd” and “offensive,” court records obtained by the authors show. The Act has since closed.

Russian President Vladimir Putin, Aras Agalarov, Rob Goldstone, Emin Agalarov, Donald Trump and Olivia Culpo. (Photo illustration: Yahoo News; photos: Mikhail Svetlov/Getty Images, Jeff Bottari/AP, Adriel Reboh/Patrick McMullan via Getty Images, Victor Boyko/Getty Images, Maxim Shemetov/Reuters)

There is no record of what acts were performed there the night Trump attended. The so-called Steele dossier, prepared by former British spy Christopher Steele, contains allegations that while in Moscow later that year Trump had prostitutes urinate on a bed in his hotel room — an episode that was supposedly secretly captured by Russian intelligence agents on tape. Trump has strongly denied that allegation.

According to an account that Goldstone provided the authors, Trump’s main interest during the nightclub visit in Vegas was in securing a business deal with Agalarov and his father.

“When it comes to doing business in Russia, it’s very hard to find people in there you can trust,” Trump told Emin Agalarov, according to Goldstone’s account. “We’re going to have a great relationship.”

The excerpt published today portrays Trump in Moscow as obsessed with scoring a meeting with Russian President Vladimir Putin, whose approval would be necessary for the Trump Tower project to proceed, and with whom Trump was cultivating a largely one-sided bromance. As the time of the pageant broadcast approached, Trump kept asking, “Is Putin coming?” the authors write — and they describe how he was stood up by the Russian president, who cited a previously scheduled meeting with the Dutch royal family, which had been delayed by a Moscow traffic jam. Instead, Putin sent a gift of a lacquered box, which was later delivered to Trump Tower, containing a personal letter whose contents have never been disclosed.

But, the authors write, Trump sought to hide his disappointment with a suggestion to an associate that the Miss Universe pageant could still announce Putin had attended anyway. “No one will know for sure if he came or not,” Trump said.

It was during this visit that Trump reached his deal with Agalarov’s company, the Crocus Group, to build a Trump Tower Moscow. As the authors report, the deal was memorialized with a formal “letter of intent” between the Trump Organization and Crocus — and the project was to be financed by Sberbank, which was majority-owned by the Russian government. Donald Trump Jr. was placed in charge of the project.

In February 2014, Ivanka Trump flew to Moscow to scout potential sites for the project with Emin Agalarov. But international events would quickly intervene. Weeks after Ivanka’s visit, the Obama administration and the European Union imposed tough sanctions on Russia in response to Putin’s annexation of Crimea and his military intervention in Ukraine. It would be a kick to Russia’s faltering economy, already struggling because of the plummeting price of oil. And one round of sanctions imposed by the EU targeted Russian banks in which the Russia government held a majority interest — that included Sberbank.

In this environment, the plans for the Trump Tower in Moscow crumbled. According to the Trump Organization, Ivanka Trump, after touring Moscow with the younger Agalarov, killed the deal for business reasons. But Goldstone, Emin Agalarov’s publicist, suspected the demise of Trump’s project with the Agalarovs influenced Trump’s view of sanctions: “They had interrupted a business deal that Trump was keenly interested in.”

Still, Trump stayed in touch with Emin Agalarov and Goldstone. In January 2015, nearly a year after Putin’s invasion in Ukraine, Trump had Emin Agalarov and Goldstone as guests to his office in Trump Tower.

The future president, Goldstone recalled, was watching a rap video that ridiculed him. Goldstone asked, “Have you listened to the words?”

Trump replied, “Who cares about the words? It has 90 million hits on YouTube.”

And Trump said something telling to Emin, who was still seeking fame as a singer after performing at the Miss Universe contest in 2013: “Maybe next time, you’ll be performing at the White House.”

Seventeen months later, in June 2016, Goldstone would return to Trump Tower — this time escorting a Russian-led delegation dispatched by the Agalarovs, offering potentially derogatory information on Hillary Clinton, courtesy of the Kremlin, to the top officials of Trump’s presidential campaign. That visit — and the Trump White House’s responses to questions about it — have become a prime focus of Mueller’s investigation.

Emin Agalarov has not yet performed at the White House.

_____

Read more from Yahoo News:

Democrat reiterates doubts about Jared Kushner’s loyalty to the U.S.

A new generation of anti-gentrification radicals are on the march in Los Angeles – and around the country

In exile with Bill Kristol, the Republican resister-in-chief

Seven days in Trumpland: Confusion, scandals and indictments

Photos: Another snowstorm pounds the Northeast

#_author:Jerry Adler#_revsp:Yahoo! News#_lmsid:a077000000CFoGyAAL#_draft:true#_uuid:d64797d0-3a1f-359f-8ccf-b9cb17ece59e

0 notes

Text

Jefferson's 'tree of liberty,' and the blood of schoolchildren

On the second day of the Republican National Convention, Ohio Minutemen gather in downtown Cleveland to express their feeling on the 2nd amendment in Cleveland, Ohio, July 18, 2016. (Photo: Carolyn Cole/Los Angeles Times via Getty Images)

Like all Americans, I have a Second Amendment right to own a firearm. I may not choose to exercise it, but the Supreme Court, in the 2008 case of D.C. v. Heller, is pretty clear on the subject. I don’t even need to be part of a militia, which is good, because I wouldn’t know how to join one. So I accept gun ownership, in principle, as part of my birthright, and acknowledge that the same rights accrue to people who might, for one reason or another, hate me. As Mickey Kaus once wrote, if liberals interpreted the Second Amendment the way they interpret the rest of the Bill of Rights, there would be law professors arguing that gun ownership is mandatory.

Why would I need one, though, except to commit a crime? Why does anyone?

For hunting, obviously. Although I do not hunt, I recognize it as essentially harmless, except to the animals who are killed, and to people who get shot by mistake, including occasionally the hunters themselves. But shotguns and single-shot rifles are rarely used in crimes and I know of no serious proposals to ban them.

For target shooting, as a sport. I have done this, and I enjoyed it. Encouraging better marksmanship is a worthy national goal, and if we keep it up the U.S. Olympic team might hope to someday win a medal in biathlon.

For personal defense. I consider myself an expert in this field, having lived in New York City my whole life, including some years in the 1970s when I would go home on the subway after leaving work at 1 a.m. There were occasions when I wished I had a handgun, but with the benefit of reflection, it’s obviously a million times better that I didn’t, for me as well as for all the obnoxious drunks who nearly threw up on my shoes. Having survived to this point, I am content to entrust my safety to the very excellent protection of the NYPD, but I also recognize that other Americans, in different circumstances, might come to a different conclusion. If – hopefully after weighing the dangers of a handgun being found by a child, or fired by accident, or used to commit suicide or murder a family member during an argument – a competent adult decides he or she needs one, then by a 5-4 majority on the Supreme Court, they have that right.

But the subject on everyone’s mind now is not handguns but rifles, in particular assault-style rifles such as the AR-15, which are the weapon of choice in random mass shootings such as the recent ones in Parkland, Fla., Sutherland Springs, Texas, and Las Vegas. Why would a law-abiding American citizen want to own one of those?

To wage war against the government. There are many contenders for the worst ideas to emerge in the wake of the Parkland massacre, but I’d like to nominate this column by National Review writer David French — the same guy whose name was briefly floated as a sane conservative third-party alternative to Donald Trump in 2016. French argued against banning semi-automatic assault-style rifles on the grounds we might need them to fight a reprise of the American Revolution. After all, you can’t take on the United States military with guns meant to shoot ducks and paper targets. French acknowledges that ordinary citizens wouldn’t stand much of a chance against the 101st Airborne, but, he writes: “for the Second Amendment to remain a meaningful check on state power, citizens must be able to possess the kinds and categories of weapons that can at least deter state overreach, that would make true authoritarianism too costly to attempt.”

And: “to properly defend life and liberty, access to assault weapons and high-capacity magazines isn’t a luxury; it’s a necessity.”

The idea that Americans should arm themselves to fight “state overreach” is a staple of gun-rights groups and politicians occupying the political terrain that runs rightward roughly from the NRA to the edge of the Earth. It goes back at least to Thomas Jefferson, who wrote that “the tree of liberty must be refreshed from time to time with blood of patriots and tyrants.” In 2010, Republican Senate candidate Sharron Angle notoriously floated the idea of “Second Amendment remedies” against Congress. Texas Sen. Ted Cruz invoked it in a 2015 fundraising email, which prompted Sen. Lindsey Graham to respond tartly that “we tried that once in South Carolina.” In view of how the Civil War turned out for the Confederacy, “I wouldn’t go down that road again.”

Indeed. If Cruz is seriously concerned about having to fight “governmental tyranny,” he might want to reconsider his support of President Trump’s military buildup, which could only make it harder. As long ago as the 1950s, when there were mutterings in the South about renewing the hostilities that were suspended at Appomattox, Louisiana Gov. Earl K. Long taunted the arch-segregationist political boss Leander Perez: “What are you going to do now, Leander? The Feds have got the atom bomb.”

Well, one solution would be to get your own atom bomb. As far as I can tell, no one is seriously asserting that the Second Amendment conveys a private right to own nuclear weapons — not even the National Rifle Association, probably not even Gun Owners of America, a group composed of people who consider the NRA insufficiently zealous, and which claims 1.5 million members. The group does, however, seek to legalize machine guns, which would at least slightly improve the odds of going up against the Marine Corps.

A lot of this is just posturing, of course: The NRA’s key stakeholders are gun companies, and it serves their interests to hype the threat that “jack-booted government thugs” are coming to arrest grandma and confiscate her Derringer. The NRA’s Dana Loesch made news last week with a claim that the mass media “loves” mass shootings because of the ratings they bring. Leaving the despicable nature of the charge aside, it is a fact that publicized incidents of gun violence have benefitted the firearms industry by spurring sales to patriots scared that this time Nancy Pelosi really is coming to take away their guns. Remington filed for bankruptcy protection this month amid a general slump in gun sales that set in right after the 2016 election, when gun owners could relax in the knowledge that Hillary Clinton’s evil designs on the Second Amendment had been thwarted.

But quite a few Americans apparently agree with French on the danger that Washington might someday decide to pick up where George III left off and reimpose the Stamp Act or force Americans to quarter troops in their homes. Banding together in militias like the so-called three-percenter movement, they are preparing to meet that threat with AR-15s.

Members of self-described patriot groups and militias run through close quarter combat shooting drills during III% United Patriots’ Field Training Exercise, which they describe as the largest patriot event in the country, outside Fountain, Colo., July 29, 2017. (Photo: Jim Urquhart/Reuters)

Of course, the same qualities that make assault-style rifles so precious to self-appointers defenders of American freedom also make them the weapon of choice for those who want to kill as many schoolchildren as possible. A ban on the sale of these weapons took effect in 1994, with a 10-year sunset provision, and after it expired in 2004 it was not renewed. There is little evidence that the ban did much to reduce gun violence, or even sales of the weapons it was meant to control. With minor modifications in design, functionally equivalent variants of the AR-15 slipped through the cracks. The chances of the same ban being reinstated now are probably nil, in a political climate in which Trump’s first instinct after the Parkland shooting was to call for arming schoolteachers so they could shoot back. In a Saturday interview, Trump went further and suggested raising the minimum age to buy a rifle from 18 to 21. Trump confidently predicted the NRA would go along with the new age requirement, which the group has long opposed.

The NRA has informed Trump that he’s mistaken.

One way to achieve at least some of the benefits of banning assault weapons would be limit the number of bullets they can hold. The gun-control organization Sandy Hook Promise is circulating a petition for a law to ban rifle magazines holding more than ten rounds, forcing shooters to stop to reload more often. The young man who shot up Sandy Hook elementary school carried 30-round magazines, but even so, according to Nicole Hockley, whose son Dylan died in the attack, 11 children managed to escape in the seconds it took him to swap in a new one. If Trump seriously believes in arming teachers, limiting magazine size should be a change he supports, because even if they managed to draw their handguns, their only hope of standing up to a gunman firing off an AR-15 is to wait for him to reload.

I predict that assault-style rifles will be around for the foreseeable future, and I suspect one will be used again, sooner or later, to slaughter Americans in a church or office or school. And — call me naïve — but I would much sooner entrust my freedom to America’s justice system, which is also part of the Constitution, than to a bunch of middle-aged guys running around the woods in camo pants, no matter what kinds of guns they have.

I hope I am never forced to put my life on the line to defend liberty, and if it should happen, I hope I have the courage to do so. But that’s not a risk I would take with the life of someone else’s child.

_____

Read more from Yahoo News:

House Democrats seek 20 to 30 more witnesses in Russia probe, but GOP resists

Meet the teen girl behind the National School Walkout movement: ‘We are motivated, passionate people’

Author Eric Metaxas, evangelical intellectual, chose Trump, and he’s sticking with him

Politics Meet the teen girl behind the National School Walkout movement

Photos: Scenes From CPAC 2018

#_author:Jerry Adler#_uuid:8aa8f05d-db9d-36d2-bb85-8ca954f0137c#_revsp:Yahoo! News#_lmsid:a077000000CFoGyAAL

0 notes

Text

The hallelujah cure: Trump campaign adviser says pray away the flu

Photo: Yahoo News photo illustration; photos: AP, Getty Images

Brethren, our topic for this week’s column is the flu, because I have it.

I followed the advice of the Centers for Disease Control and got a vaccination, which may or may not have lessened my symptoms. But then I discovered I had neglected the most important prophylaxis of all: prayer.

This advice came from the evangelist Gloria Copeland, who with her husband, Kenneth, runs a religious empire based largely on faith healing. Copeland posted a video last week that argued, passionately if incoherently, either that the flu doesn’t actually exist (“We got a duck season, a deer season, but we don’t have a flu season”) or that faith can protect you from it (“inoculate yourself with the word of God”).

At a time when the CDC was warning that this year’s flu outbreak appears to be the worst in almost a decade, Copeland’s remarks went, uhh, viral. They also attracted unwanted attention to her connection to Donald Trump’s presidential campaign, on whose “evangelical advisory board” she and her husband served, alongside prominent Christian and Republican figures including Jerry Falwell Jr., Michele Bachmann and James Dobson. Apparently in response, a clarification went up on the Copeland Ministries website, insisting that “Gloria did not say or imply that you shouldn’t get a flu shot or see a doctor. Gloria and Kenneth Copeland Ministries value medicine and doctors and would never counsel someone not to seek medical care.”

That disclaimer would be more convincing if there weren’t copious evidence that Copeland actually does not value medicine, at least in comparison with the kind of healing that goes on in her church and at revivals. Her statement on the website was followed by pages of testimonials like this one, from “Terri”: “Tests showed I had a growth on my gallbladder and the doctor recommended surgery. We prayed and received healing by faith. Hands were laid on me and I never had another symptom.” As Copeland once preached: “We know what’s wrong with you. You’ve got cancer. The bad news is we don’t know what to do about it — except give you some poison that will make you sicker. Now, which do you want to do? Do you want to do that, or do you want to sit in here on a Saturday morning, hear the word of God and let faith come into your heart and be healed?”

At least since the time of Jesus, Christians have prayed for health. But Kurt Andersen, in his indispensable guide to American irrationality, Fantasyland, traces contemporary faith healing to the advent of the charismatic, ecstatic form of Christian worship known as Pentecostalism. After its heyday in the early decades of the 20th century, it was banished to the fringes of society for decades, only to reemerge in recent years under the guise of “prosperity gospel.” As preached by the Copelands, Oral Roberts, Joel Osteen and many others, one can think of prosperity gospel as a form of “applied religion,” by analogy to, say, “applied science,” that involves trying to obtain concrete rewards in the here and now, including financial success, personal happiness and overcoming adversity.

Such as the flu.

Andersen notes that this is not a practice confined to right-wing Christians. Seeking to cure cancer by praying is not more or less implausible than using crystals for the purpose. Oprah, that great font of national gullibility, was an early exponent of “The Secret,” a best-selling book by Rhonda Byrnes that repackaged prosperity gospel in secular form as “the law of attraction,” the idea that “the universe” would provide whatever you sought if you just thought about it long and hard enough.