Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Critical Analysis

Plass J. L., Homer B. D., MacNamara A., Ober T., Rose M. C., Pawar S., Hovey C. M., Olsen A. (2020). “Emotional design for digital games for learning: The effect of expression, color, shape, and dimensionality on the affective quality of game characters”, Learning and Instruction, Volume 70, pp. 1-13. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2019.01.005.

In the world of game-based learning, the use of emotions has garnered a special type of attention over the years, as the need for a more dynamic learning method has been growing. Researchers from New York University dive into this topic in their article entitled “Emotional design for digital games for learning: The effect of expression, color, shape, and dimensionality on the affective quality of game characters”. In their writing of the text, the authors reflect on the affective qualities the design of game characters might have on adult and adolescent learners through the adoption of the Integrative Model of Emotion in Game-based Learning (EmoGBL). I have chosen to analyse pages 3-5 of this text, which examine the link between emotional design and intellectual stimulation mechanisms.

While the authors are professionals in the field of education, they base their studies on major empirical findings and ideas that demonstrate the relevance of recognizing emotion as a fundamental component of learning, cognition, and instruction. In the first paragraph of page 3, according to the EmoGBL model, emotions have a significant impact on four critical cognitive and motivational mechanisms: attention allocation, memory storage and retrieval, problem-solving, and motivational tendencies and behaviours. Most positive inducing feelings, such as pride and curiosity, have been proven to increase the desire to learn, whilst negative deactivating emotions, such as boredom and frustration, have been shown to decrease motivation. When examining the valence or affect and arousal of emotions in the scope of self-regulation, a more sophisticated perspective emerges. While happy emotions conveyed by visual design have been demonstrated to lessen the cognitive load and maintain attention levels, not all pleasant emotions lead to desirable learning results. Some positive emotions elicited by memory recall relating to personal experiences, for instance, have been proven to be detrimental to learning. This duality made me realise how we often generalise the usefulness of positive emotions, while we disregard the value of creating a customized approach to emotional design in GBL spaces to fit specific learning needs. Another discovery was that materials with warm colours and round shapes turned out to produce more positive emotions and a better understanding and transfer of scientific information, compared to materials with neutral colours and square shapes. Additional research mentioned that high arousal levels in games produce greater increases in cognitive skill than ones with low arousal, particularly for learners older in age or lacking previous experience in analytical aptitude.

The article explains how the EmoGBL model investigates both proximal and distal emotional antecedents, offering some insight into the complex systems that drive emotional reactions in game-based learning. Appraisals and emotional transmissions are proximal antecedents, with appraisal processes reflecting learners' judgments of themselves and circumstances, and emotional transmissions originating from real-life or virtual peers. These mechanisms are consistent with appraisal theories, which claim that emotions and our perception of events are inseparably connected, suggesting a subjective side to assimilation and learning. Through the model, the authors divide appraisal-related emotions into several categories, including achievement motivations (from desires of success and competence), epistemic emotions (from acquiring new knowledge), social emotions (from interaction, collaboration, or competition), topic emotions (from personal values and interests), aesthetic emotions (from the pleasantness of audio and visuals), and technological emotions (from the satisfaction or dissatisfaction with the interface). Furthermore, emotional transmission procedures like entrainment, contagion, and empathy reveal the interdependence between learners and the gaming environment, further contributing to the complex emotional landscape.

According to the article, players are more willing to connect with virtual characters in a game when their facial expressions convey a spectrum of emotions and when they consider the character to have human features. For this reason, the researchers decided to look into the four visual attributes of shape, colour, expression, and dimensionality to comprehend their influence on emotional design for GBL characters. Facial expressions, a distinguishing design aspect of game characters, are investigated in the article for their ability to cause emotional contagion, with both positive and negative expressions expected to increase arousal. The baby-face bias is triggered by visual form for example, which includes rounded features, large eyes, tiny noses, and short chins, reflecting helplessness, innocence, and sincerity. When talking about colours, warm tones, particularly orange, have been discovered as powerful elicitors of arousal, while the colour green, high in saturation, is able to instil hope, growth, and success. Red which usually indicates danger, means failure in the context of learning. It is very interesting how we are able to utilize colours and their arbitrary meanings to our advantage when dealing with learning material. The authors shift to studying the effect of dimension by comparing 2D and 3D graphics, which is extremely insightful. In fact, the usage of 3D visualizations has been proven to provide more potential for emotional affect. Characters that are displayed in 3D are expected to have more potential to push emotions to extremes when compared to 2D counterparts. This explains why most of us feel more captivated by 3D characters in cartoons and movies for example, even when we have more appreciation for the artistic craftsmanship in the design of 2D personas. An interesting point the authors made as well is how there are more options for integrating presence-inducing signs of the babyface bias in inanimate objects when rendering a game in 3D.

In the end, the EmoGBL framework illustrates the significance of emotional design in shaping learners' emotional experiences in game-based settings. The paper emphasizes the importance of experimental research and manipulations in unravelling the role of emotional affect in learning. It underlines the importance of a sophisticated approach to emotional design which was not available in traditional learning systems. I feel like adopting a GBL approach instead of the outdated teaching methods during my past studies could have changed my relationship with my studies for the better. Nonetheless, future research should look more into the impact of larger societal and cultural factors on emotional reactions as GBL evolves.

0 notes

Text

Reader

1.

Plass J. L., Homer B. D., MacNamara A., Ober T., Rose M. C., Pawar S., Hovey C. M., Olsen A. (2020). “Emotional design for digital games for learning: The effect of expression, color, shape, and dimensionality on the affective quality of game characters”, Learning and Instruction, Volume 70, pp. 1-13. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2019.01.005. [Accessed 2 January 2024].

In this paper, the authors discuss the use of emotions in video games, especially for learning. They present the many benefits of implementing affective strategies in game-based learning to give students motivation through emotions. The text takes character design as the main centrepiece of the study, and how it can help improve memory, attention, and perception for learners. More precisely, the study demonstrates technical models of affective character design that lead to better integration of verbal and visual information in the learning process. Four visual attributes of emotional design for game characters were presented: shape, colour, expression, and dimensionality. I found most interesting the differentiation between 2D and 3D by the researchers. The studies showed that there is a higher level of arousal with characters that are made in 3D (VR) rather than in 2D, which exhibits better affective qualities and improves immersion for students regardless of age and sex.

2.

Domsch S. (2013). Storyplaying: Agency and Narrative in Video Games, De Gruyter, Inc. Berlin/Boston. Chapter 2, pp.13-17. Available at: https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/herts/reader.action?docID=1000613&ppg=4. [Accessed 2 January 2024].

The author explores the relationship between gameplay, narrative, and rules in video games, called Fictional Worlds (FNs). This portion of the book exposes the debate between narratologists who identify games as narratives and ludologists who argue the opposite. The chapter establishes a connection between video games and narrative through shared elements such as the role of rules in defining the experience, whether in games or fiction. Just like in fiction, realist games set an implicit contract between the game and the player when assuming similarities between the game world and the physical world. Video games, unlike real life, can intentionally modify the laws of physics to create gameplay elements. The text helped me understand the rigidity of video game rules that are almost unbreakable and used as control points for a player’s options. This is a distinct feature far from real-life, and crucial to add control to the player experience.

3.

Šisler V. (2008). “Digital Arabs”. European Journal of Cultural Studies. Volume 11, issue 2, pp.203–220. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/1367549407088333. [Accessed 2 January 2024].

This article analyses negative portrayals of Arabs and Muslims in Western games and their impact on gamers. The author mentions the attack on Arab culture in foreign games and brings up initiatives that reverse stereotypes and provide alternative narratives. Examples are games like Under Ash, which tackles the Israeli occupation and presents the emotional perspectives of Palestinian civilians. The article elevates the importance of reshaping self-representation and producing cultural balance through games. The concept of "digital dignity” is proposed, representing the pride Arab teenagers feel when playing games reflecting their views. The author brought my attention to the Orientalist imagery trend in video games set in the Middle East, and the stereotypes originating from the lack of depth in military conflict game depictions. Being Arab myself, the text resonated with me and helped reinforce my understanding of the origins of misrepresentation and learn ways of advocating for true depictions of identity.

4.

Shaw A. (2012). “Do you identify as a gamer? Gender, race, sexuality, and gamer identity”. New Media & Society. Volume 14 issue 1, pp. 28-44. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444811410394. [Accessed 2 January 2024].

The article addresses the underrepresentation of marginalized groups in video games, specifically individuals from the LGBTQ+ community. The author exposed the industry's limited knowledge of the diverse gamer base while focusing on the way marketing can ruin people’s relationships with games. A good point was made on how the intersectionality and complexity of gamer identity define minority individuals in the context of social interactions. I found the study very important in questioning stereotypes and examining the social construction of games rather than trying to decipher whether LGBTQ+ individuals are gamers or not. The research mentioned a strong qualitative and quantitative data analysis through a series of interviews which explains reasons some individuals stopped identifying as gamers. Nonetheless, the topic forms a strong message that developing games that are inclusive for all is much more important than questioning the identity of members of the gaming community.

5.

Donald I. (2019). “Just War? War Games, War Crimes, and Game Design”. Games and Culture. Volume 14, issue 4, pp. 367-386. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/1555412017720359. [Accessed 2 January 2024].

This article's author delves into the debates surrounding first-person military-themed shooters (FPMS) and their influence on players’ perceptions of armed combat. It mentions the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) debating breaches in games which may expose people to state-sanctioned crimes. The article presented me with relevant insights into ethical aspects I should consider as a games artist, and the need for a balance between realism and ethics. The gaming industry is responsible for conforming to international legal norms and understanding the role of non-governmental organizations in lobbying for International Humanitarian Law (IHL) adherence. When simulating violence, games should differentiate between civilians and soldiers. The author advises people to avoid IHL breaches in realistic war games and assess the influence they have on players' morals. The impact of video games on ethics is strong, as creators we are encouraged to see the larger ramifications of breaking ethical game design techniques.

6.

Bizzocchi J., and Tanenbaum T. J. (2012). “Mass Effect 2: A Case Study in the Design of Game Narrative”. Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society. Volume 32, issue 5, pp. 393-404. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/0270467612463796. [Accessed 2 January 2024].

The article highlights the challenges of designing narratives for video games, by taking Mass Effect 2 as an example. The authors highlight the contradiction between interactivity (player agency) and narrative (story coherence) and propose strategies to minimise it. They discuss their framework, including the narrative arc referring to both the overall progression of the game and micro-narratives. I found it interesting how they also consider the spatial design of the virtual world as a narrative act since it influences gameplay and storyline progression. It was valuable to see the commitment to objectivity throughout the close reading process involving both individual and joint playthroughs, shared discussion, notetaking, screenshots, and analyses. According to the article, to ensure players identify with the characters, designing them requires visual representation, goal-oriented behaviour, and psychological depth through emotions eliciting empathy. Narrative interfaces are presented as tools, enhancing the link between interactive decision-making and pleasure.

7.

Petrey G. (2022). “The affective flows of the sublime in Martina Menegon's new machinic subjectivity”, New Techno Humanities. Volume 2, issue 2, pp. 130-135. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techum.2022.04.001. [Accessed 2 January 2024].

The article inspects Martina Menegon's art piece, "Virtual Narcissus", and her innovative use of photogrammetry and virtual reality (VR). The author navigates the evolving world of digital media while predicting the rise of post-screen technologies and their reflexive qualities. The author’s analysis of ethics leads to the proposal of the evolution of cyberfeminism into Xenofeminism which refutes gender norms and biases often limiting creative practices. The text also highlights Menegon’s intentional use of basic technology to challenge norms of representation and gender objectification by embracing image imperfections and presenting her body in a black void. The article improved my understanding of the way VR increases immersion levels by extending images into the 360˚ space, compared to flat screens which form a distance between the information and viewers. In this manner, VR becomes a machine for affect flow which takes users to a state of increased immersion through the subconscious mind.

8.

Robb J., Garner T., Collins K., and Nacke L. E. (2017). “The Impact of Health-Related User Interface Sounds on Player Experience”. Simulation & Gaming. Volume 48, issue 3, pp. 402-427. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/1046878116688236. [Accessed 3 January 2024].

The text discusses sound in video games, exploring its functions from conveying information to evoking emotions. The article addresses a lack of game audio research by offering two studies focusing on player-health interface sounds. The authors explain their first study which investigates the presence and absence of health-related sounds and their impact on gameplay, revealing that players value audio feedback for crucial cues like health status. Their second study compares two types of sounds, 'abstract' and 'realistic', focusing on situational awareness and health perception. The results suggest a higher preference for realistic heartbeat sounds over abstract beeping which proves the effectiveness of realistic sounds in conveying health information and enhancing player experience. The authors offer design recommendations for audio user interface which I found helpful: alert player on damage, alert when health is below 25%, replace visual information with audio, involve audio design early on, and teach players meanings of abstract sounds.

9.

Mitchell W. J. T. (2005). “There Are No Visual Media”. Journal of Visual Culture. Volume 4, issue 2, pp. 257-266. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/1470412905054673. [Accessed 3 January 2024].

This article challenges the conventional term 'visual media' by proposing that all mediums, including television, film, photography, and painting, engage the senses beyond just vision. It questions the categorization of some media as merely visual, especially painting, which unveils the presence of critical discourse and language even in supposed optical artworks. The writer argues that the sense of touch is inherent in every handmade object, notably painting, same for architecture, sculpture, and photography which aren't purely visual either. I found it interesting how the erasure of the notion of visual art is slowly happening, with mixed media and conceptual art challenging traditional belief, and enabling a more nuanced media classification. This helped me understand that all mediums are, in essence, mixed media. Their specificity involves a complex interplay of emotional, sensory and semiotic elements, which is why a new taxonomy using sign functions as core elements of media is needed.

10.

DeVane B., and Squire K. D. (2008). “The Meaning of Race and Violence in Grand Theft Auto: San Andreas”. Games and Culture. Volume 3, issues 3-4, pp. 264-285. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/1555412008317308. [Accessed 3 January 2024].

The article focuses on whether Grand Theft Auto: San Andreas offers spaces for agency within a semiotic system of race and violence, especially for young players from disadvantaged backgrounds. The game is examined through cultural dimensions, like the portrayal of African American males as hyper-violent. GTA is depicted as an open-ended play space, introducing a concept I found helpful, "field of meaning", which describes video game content as a non-uniform process shaped by social, cultural, and contextual influences. Conducted with three groups of "at-risk" youths, the research shows that hardcore gamers acknowledge aggression's transferability, but can’t identify the "wrong person" affected, children. Athletes differentiate between in-game and real-world violence but understand the influence of violent content on some. Casual gamers show varied interpretations, as the individual went from disinterest to interest in violence when put with others, suggesting that social interactions play a role in shaping perspectives.

0 notes

Text

Blog Post 10: Affect Techniques

This post is interrelated with the previous one. It discusses techniques for implementing emotioneering in video games more precisely and lays out the various reasons that promote the integration of emotions in games.

Since video games are becoming increasingly popular each year, it has become the mission of developers and designers to unify all gaming experiences regardless of age, gender, and skill level. Creating the same user experience can be tricky when dealing with interactive simulations like video games as gameplay relies heavily on human decisions and input. Some people might argue that games with procedural content generation might make it more difficult to accomplish the mission of creating a unified experience since it depends on the subjective outlook of players after all. On the other hand, I believe that removing the procedural aspect from games will simply make them less dynamic and will not solve the problem at hand. In fact, the research focus should be on finding ways of achieving the same levels of player satisfaction within all experiences of a certain game, regardless of the way the game was played.

There are many methods of measuring user enjoyment, and results could be useful to improve the game design process overall. Hence, comes the value of affect in video games as well as the study of emotions during the game design process, and after player testing. Some video game scientists claim that the increase in diversity of the gaming community is making it much more complicated to identify an ideal player that could be used as an index for research. Therefore, the type of need for affective design will differ from one player to another. It is also stated that when people enjoy playing a certain game, they are more likely to overlook its design flaws. As a result, there is a greater need to comprehend the functions of emotions and the processes that are influenced by them (Ng, Khong, Thwaites, 2012).

It is no secret that "Games that involve a player emotionally will gain a competitive advantage" (Freeman, 2004, p.3). So, it goes without saying that it is worth it for game companies to invest in the study of emotions and their use in the design of video games. Some of the many techniques of emotioneering focus on storytelling, NPC writing, and dialogue. In reality, there is a clear distinction between writing stories for games and writing stories for film. For video games, writers should take into account the many possibilities of changes to the plot, or else players will feel like they are being forced into a specific narrative they do not identify with. Not only that, but when integrated correctly in the storyline, plot twists can build a sense of belonging for players in the game, especially when it involves concepts such as trust, regret, and betrayal. Interactivity depends on the involvement of the person playing the game, and without that emotional attachment, the interaction will be broken.

The same can be said about the creation process for NPCs (non-playable characters) that play an important part in binding the emotional structure between the game and player. For example, defending or protecting an NPC will strengthen the affective link in video games, and will make it easier for the player to picture themselves in the position of the main character. There are many realism techniques when it comes to NPCs, but one of the most prominent ones is dialogue. Choosing how NPCs present information to the player can help add some depth and believability when they are given human traits like concern, empathy, and disapproval, for instance. On occasions, NPCs can even be seen putting on masks to adopt emotional facades and enhance their perceived humanity. For instance, when approaching an NPC, you may receive a cheerful greeting, only to later overhear that same NPC conveying contrasting emotions once you have moved away. Such game features add great emotional depth to video games, thus making them more affective (Freeman, 2003).

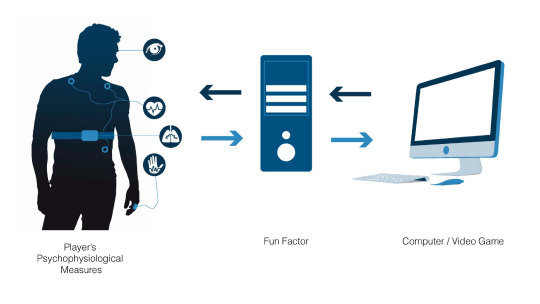

There has been a quest to predict players' emotions during gameplay, which has been fueled by the objective of utilizing player data as real-time indicators of user experience in affect-aware systems for adaptive games. Preliminary trials in this domain, have mainly concentrated on relatively simple adaptive game features like difficulty levels, or single measures of affect like facial expressions. Notably, the potential of affective gaming has evolved from static reactive systems to complex frameworks capable of adjusting game settings depending on a player's physiological signs. A research team in this field is Dekker and Champion (2009) who undertook an influential study in a survival horror game that dynamically adjusts itself during gameplay in response to players' psychophysiological signals. The study resulted in a notable preference of 64% of participants for the adaptive version, compared to 36% for the non-adaptive version. However, despite advancements in user experience after implementing the affective system, the findings revealed significant overlap in the measurement of stress and workload for example. This indicated that technological progress in intelligent systems may have been outpacing the cognitive and neuroscience research upon which the developments of adaptive games were grounded (Chamberland, C., Grégoire, M., Michon, P.-E., Gagnon, J.-C., Jackson, P.L. and Tremblay, S., 2015).

There is another similar project called FUNii. It had the objective of creating a system capable of predicting and maximizing the player's experience of fun by constantly adapting the parameters of a game. Its system combines a player's physiological signals and in-game behaviours to adjust the settings according to the detected fun levels and the preset goals. The development process involved steps like collecting continuous psychophysiological and behavioural variables associated with fun, developing algorithms to efficiently extract these indicators, and building a real-time adaptive system made to alter game parameters based on the player's fun. The project comprises three phases. The first one involves experimentation to model the relationship between psychophysiological signals, in-game behaviours, and continuous fun ratings. The second part focuses on developing three game versions: no adaptation, random-based adaptation, and PBMF (Psychophysiological and Behavioral Model of Fun) adaptation. The third one illustrates the benefits of PBMF-based adaptation, using data, compared to random and no adaptation conditions. This study combined the continuous, real-time measure with traditional review questionnaires: after they were done playing the game, individuals were asked to rate their fun levels on a scale from -100 to 100 while watching a playback of their gameplay. This research proved that self-calibration is the optimal technique to assess player fun. It emphasizes its dynamic and continuous nature as well, as opposed to static memory recall ratings. This same technique can also be applied to game features extending beyond fun factors, so, it serves as a reliable tool to assess affectiveness in states of frustration for example. (Chamberland, C., Grégoire, M., Michon, P.-E., Gagnon, J.-C., Jackson, P.L. and Tremblay, S., 2015).

Finally, the importance of emotioneering, user-centred design, and affect assessment cannot be emphasized enough. Putting emotions at the core of design processes is crucial to achieve maximum flexibility, which is needed to ensure the functioning of affective applications. Such methodologies allow for the detection of severe issues that are usually not apparent through user testing alone. In essence, the layering of design techniques and emotioneering principles into the production of video games results in more engaging interactive gaming experiences.

Sources:

Ng Y.Y., Khong C.W., Thwaites H., 2012. A Review of Affective Design Towards Video Games. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences. [e-journal] Volume 51, pp. 687-691. Available at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1877042812033630. [Accessed 1 Jan 2024]

Freeman D., 2004. Creating emotion in games: the craft and art of Emotioneering™. Comput. Entertain. [e-journal] 2(3). Available at: https://doi.org/10.1145/1027154.1027179 [Accessed 1 Jan 2024]

Freeman D., 2003. Creating Emotion in Games: The Craft and Art of Emotioneering.[e-book] O'REILLY. New Riders. Available at: https://learning.oreilly.com/library/view/creating-emotion-in/1592730078/. [Accessed 31 Dec 2023]

Chamberland, C., Grégoire, M., Michon, P.-E., Gagnon, J.-C., Jackson, P.L. and Tremblay, S., 2015. A Cognitive and Affective Neuroergonomics Approach to Game Design. Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting. [e-journal] 59(1), pp.1075–1079. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/1541931215591301. [Accessed 31 Dec 2023]

0 notes

Text

Blog Post 9: Emotions & Games

This blog article delves into the presence of emotions in video games and their role in creating a holistic experience. The concept of "affect" and some of its applications for developing subjectivity in games will also be explored.

Ever since their emergence, there have been discussions revolving around video games and the effects they have on people, especially children, and their personality-building. The question has always been about whether video games can induce violence and other negative habits in children and young adults. Many studies and research that took place over the years help us understand that games do not directly impact the human brain by creating these bad traits. They in fact bring out the tendencies players may already have, and uncover them or sometimes even unintentionally encourage them. For this reason, it is always important to find the root problem behind these types of behaviours instead. This brings us to the more important question which seeks to understand how emotioneering in game design can help tackle insensitivity in video games.

To begin, I'd like to introduce a terminology, "affect", which I will be using throughout this blog. According to Gregg and Seigworth, It "is the name we give to those forces...that can serve to drive us toward movement, toward thought and extension" (Gregg and Seigworth, 2010, p.1). It is a visceral force with no beginning or end that frequently targets the subconscious mind and clings to humans in the form of emotions. It also represents our capacities to constantly affect and get affected by other entities, which proves our never-ending immersion as humans within the world's signals (Gregg and Seigworth, 2010).

Affect has been particularly more successful in games than other types of media since the interaction between humans and computers seems to be the richest and most dynamic between all mediums. The level of immersion that is created by video games overall allows for experiences that are more dense in emotions and feelings. In fact, research in emotioneering via games has led to advancements in the field of affective simulations. The inspection of emotions in games has provided completely new techniques and solutions at all development stages of the affective side of a game. In fact, good affect strategies have been associated with the successful elimination of biases in personal player experiences that contain features like procedural content generation. Another reason why games excel in affective interactions is due to their diverse composition, which incorporates characters, music, sound effects, speech, and virtual cinematography, that are guided towards enjoyable game mechanics. This complexity provides a level of personalisation that effectively evokes emotions. In return, players are willing to contribute their personal input to researchers of emotion, as long as it enhances their gaming experience. Consequently, players are prepared to go through a rollercoaster of emotions, such as frustration, anxiety, and fear, in pursuit of immersion and advanced emotional engagement during gameplay. (Yannakakis, Isbister, Paiva, and Karpouzis, 2014).

As stated by Will Wright in David Freeman's book on the art of emotioneering, early games predominantly catered to our primal instincts, tapping into the basic impulses we get from the central region of our brain known as the "reptilian" brain stem. As time went on, we started seeing the emotional scope of games which has transcended the basic survival and aggression motif and has evolved to encompass themes of empathy, nurturing, and creativity. From Wright's notion, we can sort of understand why the earlier versions of survival games did not succeed at realising strong connections with gamers. He suggests that even during prehistoric times, human beings depended on more than basic provisioning and shelter to survive since group life was based on understanding and predicting others as well. This is the origin of sympathy, an ability that guides all human interactions and a crucial skill to be able to simulate other people's thoughts and experiences in our minds (Freeman, 2003). Similarly, to be able to feel connected to the main character of a game, it should be easy for players to put themselves in the protagonist's shoes and understand the virtual world they are experiencing. This is only made possible through emotioneering, a technology proposed by Freeman, which relies on utilising emotions to immerse players in the world existing within a video game. (Freeman, 2003)

As video games are highly reliant on human input, it is almost impossible to depend on stories alone to inflict emotions on players. This is where Wright makes a distinction between linear entertainment (movies, plays, etc...) which is passive and receptive, and interactive entertainment which actively requires human involvement to function. For example, "When a player loses control of the joystick or mouse, it's similar to watching a movie when the screen goes blank. You've just closed down the primary feedback loop" (Freeman, 2003, Foreword). This type of agency adds another layer of immersion in games which only exists because of their unpredictable nature. Of course, games do have pre-scripted storylines for the most part, but nonetheless, it is the player's empathy towards the character and their reflection of the story that determines future actions and decisions in-game.

In the end, since video games have a high impact on an individual's personality, it is important to harvest these affective properties as opportunities to instil positive traits in people. We often find games with hostility and crime but we rarely find ones that promote good character and behaviour. One thing that remains at the top of my mind is how even though the game The Witcher contains many aspects of violence, we can give credit to the way the main character is written. Geralt can be regarded as a positive role model. His character embodies virtues such as resilience, resourcefulness, and a strong sense of morality. All throughout the game, he can be seen demonstrating a commitment to justice and ethical considerations, as well as some shape of parenthood. The inclusion of affect and the use of emotioneering in video games, like The Witcher, not only enhances the gaming experience but also offers an avenue for personal growth. When built to stimulate emotions, video games have the potential to be great instruments for narrative, empathy-building, and moral development.

Sources:

Gregg, M. and Seigworth, G.J., 2010. The Affect Theory Reader. [e-book] Google Books. Duke University Press. Available at: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=bl0udWQii48C&lpg=PA1&ots=nsva1Gd_1P&dq=melissa%20gregg%20and%20gregory%20seigworth%20affect&lr&pg=PR4#v=onepage&q&f=false [Accessed 31 Dec 2023].

Yannakakis G. N., Isbister K., Paiva A. and Karpouzis K., 2014. "Guest Editorial: Emotion in Games". IEEE Transactions on Affective Computing. [e-journal] vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 1-2. Available at: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/6812170 [Accessed 31 Dec 2023]

Freeman D., 2003. Creating Emotion in Games: The Craft and Art of Emotioneering.[e-book] O'REILLY. New Riders. Available at: https://learning.oreilly.com/library/view/creating-emotion-in/1592730078/. [Accessed 31 Dec 2023]

0 notes

Text

Blog Post 8: Game Semiotics

This blog post will serve as a way for me to exemplify the use of signs in video game construction. By making use of researchers' outlook on semiotics, I will try to talk about the ways signs are used in video game creations that have been released throughout the years.

When semiotics was first discussed, it was believed that signs have an arbitrary nature that determines meaning. As presented by Ferdinand De Saussure (1959), there is no direct correlation in the relationship between signifier and signified, as he believed that the meaning merely relies on social constructs and cultural understandings of representations. On the other hand, American semiotician Charles S. Peirce (1873) distinguished himself from other theorists through his proposed concept. He believed that every sign, including ideas and predictions of future events, holds a physical connection to the object it signifies. He assigns three attributes to a sign away from arbitrariness: material quality, demonstrative connection to the signified thing, and appeal to the mind. The latter is explained by an example that he made: "A weathercock is a sign of the direction of the wind. It would not be so unless the wind made it turn round" (Pierce, 1991, p.141). Taking this case in point, a weathercock has a distinct shape and material first. Second, there is a physical wind force representing a solid connection between the weathercock and the direction of the wind. Third, the weathercock is only functional as a sign of wind because it projects a signal to the human mind that comprehends it as so.

Initially, many video games require players to read signs, solve mysteries, and find evidence through riddles. This is where the first use of semiotics is detected in the scope of video game design to make sure there is clear communication between the players and the game they are experiencing. I believe that one of the biggest mistakes in studying game design is confining its purpose to storytelling. Some people consider games as a form of text which only represents the storyline it offers and believe that it can be analysed using traditional literary techniques. The reality is that in nature, the definition of a text should not be simplified in that manner when discussing it in the realm of video games. For example, would we be able to study Tetris (1985) by solely thinking of it as a written work (Bruchansky, 2011)?

To push this further, a text should actually be seen as the meaning or the content behind the creation of a game as well. David Herman explains this concept best in his writing of Story Logic (2002). He clarifies that “Narrative can also be thought of as systems of verbal or visual cues prompting their readers to spatialize storyworlds into evolving configurations of participants, objects, and places" (cited in Bruchansky, 2011, p.1). In that sense, game worlds are no longer just the environments, characters, and actions imagined by the storytellers of the game. They become directly related to the virtual world represented to players in the form of visual signs like computer graphics, and auditory ones like sound effects. It's in that way that semiotics allows individuals to appreciate the relativity of their cultural system and understand the motivations behind different types of representations within the gaming medium (Bruchansky, 2011).

In the world of semiotic analysis, numerous approaches exist, yet they all acknowledge three fundamental constituents of sign systems: representations (signs and symbols), referents (what is represented by signs and symbols), and the relationship between the two. Among these three, the interplay between the representation and the represented stands out the most (Myers, 1999). Moving beyond narratives, semiotics plays a crucial role in user interface design within video games. Signs can appear as symbols in the form of a heads-up display (HUD) which is basically the graphical user interface (GUI) of a game. It is responsible for explaining to the player the status of a character and the functionality of other elements in the virtual environment while progressing in the game. For this reason, comprehending how meaning is produced in video games requires a grasp of Peirce's triadic model of signs. To be exact, the semiotician differentiated between three types of signs: iconic, indexical, and symbolic.

Iconic

In video games, iconic signs can be seen as symbols that resemble or mirror their objects in some manner. These indicators have a direct visual resemblance, which allows the players to detect and correlate them with certain meanings at once. The health bar display in many games, for instance, is an excellent usage of iconography since it is commonly recognized as a sign of health. This helps in establishing an obvious link between the visual depiction and its real-world equivalent. Take the example of the game The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild (2017) where the heart symbol acts as a visual indicator of the player character's health state. As players, we are somehow capable of automatically interpreting the loss of hearts as a degradation in the character's well-being. This iconic usage of signs improves gameplay by offering immediate feedback and creating a smooth player immersion.

Indexical

In video games, indexes provide a direct, causal link between the sign and its object. These indicators mainly rely on observable correlations, which frequently reveal cause-and-effect dynamics. A notable example is the appearance of footsteps in the video game The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt (2015). In-game, footprints are highlighted in the mud when Geralt, the main protagonist, is tracing down a character or a monster. This operates as an indexical sign that serves real-time feedback and guides the player to the target. It is worth mentioning that indexes are used for more than just visual clues. In some horror games, the sound of heartbeats becomes more intense as danger approaches, which acts as an indicator of an impending threat. Through the use of sound effects, the player's increased awareness marks an imminent encounter with a game boss for example, creating a thrilling atmosphere and enhancing the user experience.

Symbolic

Symbolic signs in games are based on conventional and arbitrary associations, which are frequently influenced by common agreements set by members of game culture. This is one area where Peirce's view of signs as being non-arbitrary could be refuted since players must get familiar with and comprehend the meanings associated with these signs in the context of the game environment. The use of certain symbols can be considered a paradigm, a set of signs available in the context of the gaming interface, aiding players in navigation and interaction (De Saussure, 1959). The notion of a paradigm was in fact proposed by De Saussure, who as I stated earlier was a firm believer in the cultural nature of signs. One example that serves as an illustration is how keys are used in different video games as symbols to open doors. To demonstrate, the lead character of the video game Silent Hill (2006) often finds symbolic keys that can unlock doors to advance in the game. In this case, the key represents the unlocking mechanism rather than being an exact replica of an actual key. Through gameplay, players decipher the symbol, highlighting the significance of shared conventions in semiotic understanding.

Sources:

Bruchansky C, 2011. The Semiotics of Video Games. [e-journal] Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/315703967_The_Semiotics_of_Video_Games. [Accessed 28 Dec. 2023]

Peirce C S, 1991. "On the Nature of Signs.” Peirce on Signs: Writings on Semiotic by Charles Sanders Peirce, edited by Hoopes J. [e-book] University of North Carolina Press. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5149/9781469616810_hoopes.12.[Accessed 28 Dec 2023]

Myers D, 1999. Simulation as Play: A Semiotic Analysis. Simulation & Gaming. [e-journal] 30(2), pp.147–162. Available at: https://journals-sagepub-com.ezproxy.herts.ac.uk/home/sagb [Accessed 28 Dec 2023]

De Saussure F, 1959. Course in General Linguistics. Edited by Bally C, Sechehaye A, and Reidlinger A Translated by Baskin W. Philosophical Library. New York. [pdf] Available at: https://www.forgottenbooks.com/en/download/CourseinGeneralLinguistics_10009049.pdf. [Accessed 28 Dec. 2023]

1 note

·

View note

Text

Blog Post 7: Signs In Movies

In this blog article, I will try to explain the practical application of semiotics by using a concrete example of cinematic pieces. I will first be uncovering what semiotics are and explaining their importance in the world of digital media.

In definition, semiotics is the study of signs, symbols, and their meanings in diverse communication systems. It is the study of how signals work to transfer information, establish meaning, and impact human thought. Semiotics originated in linguistics and has broadened its reach to include the auditory, visual, and tactile elements, which resulted in a reliable framework for evaluating a range of cultural and artistic works. According to Berger (2018), the basic unit of semiotics is the sign which is "this unity of word-object, known as a signifier with a corresponding, culturally prescribed content or meaning, known as signified" (Berger, 2018, pp. 3). To illustrate, our minds match the word "dog" or the image of a dog, which are the signifiers in this case, to the original idea of a dog, a domesticated canine, which would be the signified (Berger, 2018). This is the main concept proposed by Ferdinand De Saussure (1916) whose ideas laid the main foundations for the world of semiotics.

Departing from these traditional perspectives, how does semiotics come into play when talking about movies? And how can we make use of this study to better understand pieces of media?

In short, signs and semiotics play an important role in defining a person's experience and knowledge of the virtual environment they explore. A movie may be thought of as a semiotic system in which every aspect, from characters and environments to visual symbols and sounds, serves as a sign transmitting meaning. The study of signs in both movies and games allows us the general public, as well as analysts, to assimilate the complex language of narration and storytelling. In the same context, we are able to decode the narrative's layers, comprehend character dynamics, and traverse stories with a greater knowledge of the complex array of meanings that are being conveyed. The world of signs is especially important in films, as audio-visual signals help evoke certain meanings or concepts. A red rose in a scene, for example, may serve as a symbolic signifier expressing romance, love or tenderness. This demonstrates how signs usually exhibit the arbitrary and culturally agreed-upon meanings set by society itself. This means that the relationship between the signifier and signified is usually not inherently connected. Instead, the connection between the two is established by social convention and cultural agreement (De Saussure, 1959). The same can be applied when discussing choices of colour tones, camera angles, and musical themes contributing to a film's semiotic language.

Semiotics in the movie: Upside Down

Upside Down (2012) is a science fiction romance film by Juan Solanas. The story takes place in a universe with twin planets that have opposing gravities. One world is prosperous and privileged, whereas the other is disadvantaged and oppressed. The plot revolves around Adam, a man from the lower world, and Eden, a lady from the higher world, and their forbidden love story. Although it hasn't received the best reactions in terms of storytelling, the film succeeded in addressing many societal topics like issues of class inequity. Through the main duality of the world, the plot exposes major ideas of social and economic divides that can be seen in the world today. In this framework, semiotics can help us dissect the messages or signs hidden within the context of this movie.

The usage of signs in Upside Down can be analysed through Roland Barthes' theory of semiotics. Barthes (1964) pushed De Saussure's ideas further by suggesting a relationship expressed by two notions: denotation and connotation. In his writing of Elements of Semiology, the French philosopher and semiotician made a distinction between "denotation", the basic apparent image portrayed by a sign, and "connotation", the deeper and hidden cultural, social, or symbolic understanding associated with a sign (Barthes, 1986). We see this for example in the film where gravity is more than just a mere physical force. It is a metaphor for societal constraints, creating segregation within the inhabitants of the universe by keeping people in their world of origin. This struggle for equality in many ways reminds me of the harsh immigration policies mainly set by Western governments to prevent people in third-world countries from moving to the "West". It can also be compared to extreme border control laws and decisions like the ones implemented in the USA to stop foreigners from entering the states from the south. In the movie, the worlds are separated by the atmosphere and are only physically connected by a tall building, the "Trans-world" company headquarters where crossings are heavily controlled. This representation (denotation) in the fictional world is a reflection and a clear sign of major corporate greed in the real world (connotation). The corporation that controls the opposite lands is highly exploitative of the world down below and its human and natural resources. This theme speaks loud to the dangers of unchecked capitalism in our contemporary age and how it affects real-life concerns.

Another way the movie highlights the differences between both worlds is through the use of colours. Different colour schemes are utilised when switching between scenes of each of the two planets, which helps viewers understand the socio-economic disparities between the two worlds. Moreover, some mythical elements were used in the writing of the movie in order to reinforce the element of desire in the relationship of the main characters. To begin with, the plot has a heavy influence from the story of original sin derived from the Book of Genesis: the main character is called Adam similarly to the first human created by God, and his lover is called Eden. Just like in the Bible where Adam was banished from the Garden of Eden after experiencing its beauty, in the film Adam is also separated from his lover Eden after experiencing her love and charm. According to the biblical text, the original couple is forbidden from eating the fruit from the tree of knowledge of good and evil but decides to disobey God’s orders and suffer the consequences. In the movie, there is a reference to the forbidden fruit, love, which is forbidden for people from opposite planets as any contact is not allowed. The main characters give into their feelings regardless and get separated in return. This echoes the theme of temptation and consequences where the main characters decide to keep seeing each other despite the societal norms and rules that prohibit their union, and experience pain as a result. This choice of symbolism in the movie connects the story to the broader human experience which makes it more universal and believable.

All in all, the aspects that are discussed in this blog highlight the capacity of semiotics to create a bridge between the digital and physical realms, offering a reflection of life with emphasised elements of focus. Both film directors and writers make use of storytelling and compositing techniques to transform their moving art from simple stories to artefacts with powers of symbolism. These can act as tools impacting human perception, hence, comes the role of semiotics in analysing and decoding the signs, thus adding depth to the film.

Sources:

De Saussure F, 1959. Course in General Linguistics. Edited by Bally C, Sechehaye A, and Reidlinger A Translated by Baskin W. Philosophical Library. New York. [pdf] Available at: https://www.forgottenbooks.com/en/download/CourseinGeneralLinguistics_10009049.pdf. [Accessed 22 Dec. 2023]

Berger, A 2010, The Objects of Affection : Semiotics and Consumer Culture, Palgrave Macmillan, New York. [e-book] Available at: https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/herts/reader.action?docID=664316&ppg=13. [Accessed 22 Dec 2023]

Barthes R, 1986. Elements of Semiology. Translated by Lavers A and Smith C. Hill And Wang. New York. [pdf] Available at: https://monoskop.org/images/2/2c/Barthes_Roland_Elements_of_Semiology_1977.pdf. [Accessed 22 Dec 2023]

0 notes

Text

Blog Post 6: Hyperreality

This is a continuation of the previous blog post that explored the meaning of reality and its manifestation. In this post, I will try to define hyperreality and illustrate its applications in the real world through different media objects.

At the core, hyperreality has always existed in our lives through our daily perceptions and through our interpretations of the universe we live in. For this reason, it is very easy to identify signs of hyperreality within human creations and media. In the modern and postmodern times, hyperreality meant the corruption of reality, as proposed by the French sociologist and cultural theorist Jean Baudrillard back in the late 20th century. In our contemporary world our understanding of hyperreality and its principles morphed, and its existence extended from simple representations and simulations into immersive experiences created by digital technologies. The embodied notion implies that media, images, and symbols alter our experiences in the shared spaces whether digital or physical, sometimes to the point where the simulated or represented reality becomes more meaningful or influential than the actual truth. Thus, it is fair to say that the expansion of digital technology, as well as the constant influx of pictures and information, contribute to the emergence of hyperreal spaces in which the distinction between the real and the virtual becomes increasingly hazy.

It is no secret that the use of mobile phones is the most widespread among all mediums nowadays. So, when we take the example of games such as Wizards Unite (2019), it is easy to understand why developers chose to build it for AR (augmented reality), which is more accessible than other platforms. Through phone cameras and screens, AR games place "the user in a world in limbo, neither entirely virtual nor real, and neither fully connected nor disconnected" (Nuncio and Felicilda, 2021, p.43). The player needs to be present in both worlds at the same time in order for the game/simulation to be complete, which creates the hyperreality state of being. In that fashion, hyperreality erases the identity of the individual and creates a new type of existence for them separate from their true one. We can also argue that players using different accounts for the same game can result in them having multiple identities existing at the same time, which is not possible in the real world, but is only possible within hyperreality. In fact, Baudrillard examines a person's entry into the simulation critically, defining four essential views which can be applied to video games. First and foremost, the game reflects a basic reality. Second, it acts as a deceptive veil, distorting a basic reality. Third, the game may conceal the lack of any basic reality. Finally, in certain cases, the game becomes a self-contained entity; a pure image separated from any basic reality. As such, forms of realism are established in gaming experiences, showing layers of intricacy in the player's existence through hyperreality. Additionally, AR games like Wizards Unite push players to go out there and explore places in their environments that they have never visited before. This ensures that people make real physical efforts to progress in the game and gain tangible or tactile experiences throughout, which gives it a much more realistic feel (Nuncio and Felicilda, 2021).

youtube

Sometimes, the earnest attempt at making creations feel realistic and human-like can lead to erasing the fine line between the natural and the synthetic. The increase of realism in the design and animation of video game characters for example was meant to raise the level of engagement of players. In fact, advanced facial rigs and animations are put in place in order to make players empathise and connect with game characters and appreciate their emotional state. The contrary was proven when people were disappointed in instances where the level of realism fell slightly below expectations and the graphics were not convincing enough (cited in Tinwell, 2014). This phenomenon is called The Uncanny Valley, a concept proposed by Masahiro Mori. It's an effect which is critically concerning in the world of 3D and CGI (computer-generated imagery), as establishing a high level of realism in characters might elicit a disturbing reaction reminiscent of the uncanny valley. Viewers may be disturbed when characters resemble human appearances but lack genuine characteristics such as natural movements, textures, and reactions. A social media trend emerged from this concept this year of 2023 where makeup artists would try and make themselves look uncanny simply by exaggerating some facial features and hiding others. Even after the makeup is done, the character represented is still recognised to be human, but the result gives viewers an eerie feeling and a high sense of discomfort. This kind of occurrence is comparable to the situation presented by Mori (1970) in his text which mentions that a prosthetic hand, despite appearing to be a human hand, falls into the uncanny valley due to its artificial features (Mori, MacDorman, and Kagek, 2012).

youtube

Similarly, movement in 3D animation has a huge impact on this effect; natural movements increase viewer affiliation, whereas unnatural or awkward motions cause discomfort. A direct example of that would be Quantic Dream's technical demo, "The Casting," which was created for the highly anticipated game Heavy Rain back in 2006 and was showcased at the Electronic Entertainment Expo. Despite emphasizing the realism of a human-like figure capable of eliciting emotions, Mary Smith the protagonist, failed to meet the audience's expectations (Tinwell, 2014). This experiment exemplified the difficulties in generating emotional resonance in virtual characters, and this situation represents a wider debate of hyperreality: the attempt to imitate authenticity in digital worlds, as shown in Mary Smith's uncanny qualities, raises concerns about the blurring lines between reality and simulation. The audience's criticism and disconnection highlight the difficulty of navigating realism and avoiding the disadvantages that the hyperreal can bring into virtual storytelling.

Sources:

Nuncio R. V. & Felicilda J.M.B., 2021. Cybernetics and Simulacra: The Hyperreality of Augmented Reality Games. [pdf] pp.39–67. Available at: https://www.kritike.org/journal/issue_29/nuncio&felicilda_december2021.pdf [Accessed 19 Dec. 2023].

Tinwell A., 2014. The Uncanny Valley in Games and Animation, A K Peters/CRC Press. [e-book] Available at: https://learning.oreilly.com/library/view/the-uncanny-valley/9781466586949/chapter-06.html [Accessed 19 Dec. 2023].

Mori M., MacDorman K. F. and Kageki N., 2012. "The Uncanney Valley". IEEE Robotics & Automation Magazine. [e-journal] vol. 19, no. 2, pp. 98-100. Available at: https://ieeexplore-ieee-org.ezproxy.herts.ac.uk/document/6213238. [Accessed 20 Dec. 2023]

0 notes

Text

Blog Post 5: Reality

For this blog post, I would like to try and define my understanding of what reality is in the philosophical sense. I would also like to discuss how reality can morph into other concepts when it shifts from the universal world to the personal, cognitive space.

As a starting point, I believe that reality is not a one-dimensional entity. Just like everything in the world that we live in, it exists and travels in three-dimensional planes. Additionally, reality has a multidirectional movement that is characterised by the exchanges of narratives between people.

Before we delve into the details, let me break down my idea for you. Fundamentally, the original form of reality is an objective existence. Reality is history; it is the direct representation of space and time and the events that took place in our universe. Epistemologically speaking, It is in fact the collective truth based on science, reason, and proof. This concept is best described by the writer Ayn Rand who states that "the primacy of existence holds that there is a mind‐independent reality, which can be perceived and understood by (human) consciousness, but which is not created or directly shaped by consciousness." (Gotthelf and Salmieri, 2016, p. 246).

However, as I stated earlier, I also believe that reality is non-linear. This means that reality is subject to changes and can take many forms when it intersects with human experience. Since reality can be perceived through the five senses, it can also generate varieties that are far from the one objective truth. Therefore, reality travels and appears differently to each person. To illustrate, when it is first discovered, the objective reality is processed by individual 1 and is then propagated as a signal to individual 2 who then in turn, interprets the reality differently and shares it with individual 3, and so on.

After having explored the topic at hand, it has become evident how the underlying fabric of reality often unveils itself in a binary nature. My claim is best demonstrated by the concept proposed by Immanuel Kant, a German philosopher who argued that the mind plays a very crucial role in shaping our experience of reality. He distinguished between "phenomena"; how things look to us, and "noumena"; how things actually exist in the world. Kant also claimed that space and time are not core entities of the external universe, but rather mental frameworks humans created to organize sensory impressions (Kant, 1998). In this manner, the subjective form of reality is no longer rooted in space and time, and it becomes the product of human experience. Reality becomes a biased truth directly related to the personal experience of an individual or the society and culture that they live in. This is where we start seeing an inheritance of a cultural reality as heritage, from one generation to the next.

It is almost impossible to have direct access and a clear understanding of the noumenal realm, we can only come in contact with the world as it appears to our minds (Kant, 1998). The best way I can describe this reflection of reality is by referring to the concept of realism. The way I see it, realism is the product of processing that the human brain uses to assimilate the exterior world. It can also be described as a method, tool, or technique to imitate the objective reality. In fact, throughout the process, the human consciousness corrupts reality and gives it a second shape.

Modern examples of realism in the current digital world are VR (virtual reality) and AR (augmented reality). Both technologies can influence or completely alter how we use and perceive our environments like never seen before. They allow us to have completely subjective experiences within the same space shared by multiple individuals. This level of realism entirely strips objective reality from its temporal and spatial aspects and creates an alternate reality that can only be understood by the person who experienced it. This is where we start speaking of an internal reality that originates from both the conscious and subconscious parts of the mind and takes shape in our world through human expression. From this notion, springs out a more intricate but related concept called hyperreality.

So, what is hyperreality? And is it completely different from reality as we know it?

The ideas discussed above form an introduction to my next blog post that will explore hyperreality in the context of media objects.

Sources

Gotthelf A. and Salmieri G., 2016. A Companion to Ayn Rand [e-book], John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated, Newark. Available from: ProQuest Ebook Central [Accessed 30 November 2023].

Kant I., 1998. Critique of pure reason. THE CAMBRIDGE EDITION ed. The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom : PRESS SYNDICATE OF THE UNlVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE, pp.1–798. [pdf] Available at: https://cpb-us-w2.wpmucdn.com/u.osu.edu/dist/5/25851/files/2017/09/kant-first-critique-cambridge-1m89prv.pdf [Accessed 30 Nov. 2023].

0 notes

Text

Blog post 4: Intertextuality and Transmedia

This is a blog post where I examine intertextuality and transmedia through some artistic interpretations that were derived from the Bible. I will also be explaining the constructive relationship that all the media objects share despite their differences.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

In order to carry out a thorough analysis, I will first begin by defining the keywords proposed. "The concept of intertextuality describes the relationship between media products where one text references another text by reusing some of its ideas and meanings" (https://media-studies.com, 2022). As for transmedia, it is the multimodal form of intertextuality. In other words, transmedia is the interaction between different forms of media objects, which leads to the merging of all their contents or their transfer from one form of media to another (https://www.futurelearn.com, n.d.). The media objects don't necessarily have to be of a similar nature as in traditional intertextuality.

Initially, the Bible has always been perceived as a single text which cannot be altered. However, the reality is that not only has the Bible seen multiple versions with translations and the divergence of Christianity, but it has formed a ground for storytelling and artistic creation in many cases as well. This dissipation of biblical concepts is an application of intertextuality in itself. But is it fair to say that this challenges the credibility of the Bible's content?

I believe that just like any other form of intertextuality, one media's representation does not negate another. In fact, all the different forms come together to create a common lexical group for the subject presented. To elaborate, each one of these representations adds to the other even if variations or negations exist between them. Each option pushes you the reader/viewer/audience to question all truths or signs offered and reinforce your belief in a specific representation of your choice. As a Christian believer myself, the concepts that were extracted from the bible (whether altered or not) and were used to produce other creations, serve as a platform for me to discuss, examine and understand the holy book even better.

it is in that same manner that all cases of intertextuality/transmedia form a holistic experience where the reader and his thoughts become the subject in focus, and the author fades away from the spotlight. It is the reader's subjective analysis and understanding of all versions presented that determines the real meaning or truth of a story and the world where it takes place.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Here are some examples of biblical adaptations over the years:

Paradise Lost

One of the earliest examples of transmedia related to the Bible is "Paradise Lost", an epic poem or a long story told in verse form. The book was first published in London in 1667. The poem narrates the story of Adam and Eve from the Old Testament and explains the creation of Heaven and Earth and the story of the original sin. This interpretation stretches the original story told by the Bible and imagines the couple’s reactions to the multiple events that led to their expulsion from Paradise. The story also shows satan's internal thoughts and reflections, his desire to rule over the world whether it is hell or heaven, and his wish to make it his own empire (Loughborough University, n.d.). All of these details were added by John Milton who transformed the book of Genesis into a 12 books-long allusion (The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2023). In this case, we can say that Milton's work is a self-conscious form of intertextuality since it represents a direct reference to the Bible and the initial story of Man, Earth, heaven, and hell. Whether it is accurate or not, his retelling of the biblical classic added more insights into the human condition and sin, and more depth and understanding of satan's rebellion, which makes the overall religious chronicle more believable.

Lucifer

A more recent series inspired by the Bible is Netflix’s Lucifer (2016). The tale follows the first fallen angel Lucifer who has grown tired of his life in hell. After retiring to Los Angeles and abandoning his throne Lucifer indulges in his favourite pastimes (women, wine, and singing). This continues until a murder happens outside of the nightclub he frequents, and for the first time in a billion years, Lucifer feels something frightening close to compassion and sympathy. He meets Chloe an appealing homicide detective who holds an inherent kindness in character, unlike what he is used to. This chain of events depicts Lucifer and his internal conflict and questioning of whether his soul has any hope for redemption (www.rottentomatoes.com, n.d.). It is very apparent that the creation of this story and its main character is highly influenced by the Bible, having satan as its main protagonist. Some of the key concepts used in the series are borrowed from the Holy Book, especially the portrayal of satan's desire for a peaceful life of entertainment away from hell. The constant reference to angels in the series and their personification as characters is also a strong indication that the storyline has direct correlations to the biblical narrative. In return, this once again proves the self-conscious nature of the intertextuality existing as a result. On the same note, we can characterise this case of intertextuality as transmedia, since the information moved from text to film, which are two different types of mediums.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

To conclude, a dynamic relationship is uncovered when exploring different forms of Media that are inspired by biblical stories. Diverse interpretations are thus revealed, which challenge the traditional perception of the Bible as an unchangeable single text. In fact, in transmedia, each version of the text adds to the collective understanding and the engagement of the reader. Additionally, intertextuality is the result of contemporary authors and filmmakers who continue to engage with the Bible in their works. On many occasions, themes and characters are directly reimagined in the context of modern storytelling as shown in Lucifer. In other instances, more subtle references to the concepts of angels and demons in media can be seen as indirect, unconscious cases of transmedia.

Sources

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2023. Paradise Lost | epic poem by Milton. Arts and Culture. [e-journal] Available at: https://www.britannica.com/topic/Paradise-Lost-epic-poem-by-Milton. [Accessed 18 Nov 2023]

www.lboro.ac.uk, (n.d.). Paradise Lost by John Milton. Loughborough University. London. [online] Available at: https://www.lboro.ac.uk/subjects/english/undergraduate/study-guides/paradise-lost/.[Accessed 18 Nov 2023]

Media Studies, 2022. Intertextuality | Definition and Examples. [online] Media Studies. Available at: https://media-studies.com/intertextuality/.[Accessed 18 Nov 2023]

FutureLearn. (n.d.). "What is transmedia?". Transmedia and Storytelling. Future Learn. [online] Available at: https://www.futurelearn.com/info/courses/transmedia-storytelling/0/steps/27333#:~:text=Transmedia%20Storytelling.[Accessed 18 Nov 2023]

www.rottentomatoes.com. (n.d.). Lucifer. [online] Available at: https://www.rottentomatoes.com/tv/lucifer. [Accessed 18 Nov 2023]

0 notes

Text

Blog Post 3: Medium Specificity

In this blog post, I will be presenting a few pros and cons of medium specificity and giving examples of real-life applications for each side.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Pros

For starters, I believe that medium specificity is essential in creating diversity in the scope of artistic expression. The theory amplifies the potential features and methods that can be utilised with each creative medium to achieve a wide variety of artistic outcomes. To be exact, each medium offers different aesthetic features such as texture, colour, and spatial compositions. This allows artists to come up with a multitude of creations that can be experienced by their audiences. As an example, traditional painting practices create a platformer for the artist to experiment with colours and textures, while sculpting allows for a manipulation of volumes, forms, and materials. Second, a great way of promoting more space for creative thinking and inventive problem-solving is through each medium's technological constraints. In fact, it’s the medium’s requirements that force artists to adjust their skills to the medium’s limitations, therefore producing unique creations. Marshall McLuhan, a Canadian philosopher is a big believer of this idea. For instance, in his book “Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man”, he claims that the transition from spoken to written language morphed than nature of communication and storytelling, which allowed more creative thinking (McLuhan, 2005). Another thing is that the emotional reactions that result from the audiences can vary greatly from one medium to another, which changes the way they interact with the art piece. Third, medium specificity holds a big role in removing constraints of the definition of art. Over the years, artistry and its practitioners have been pushing the boundaries of different mediums, which has led to the birth of new hybrid forms of artistic creations. This expansion opened gateways for novel Concepts and choices within artistic expression, which has helped produce diverse media objects that result from combinations of art forms. An early example of this concept is “Phantasmagoria”, which is an early theatre horror Show that made use of moving picture technologies back in the 1770s to produce an immersive spectator experience. This creation, which was new at the time, created a mix essentially between two mediums: drawing and lighting.

Cons

To begin with, medium specificity often results in work that is more appealing to certain audiences who are familiar with the specific medium being used. Other people who don’t have a previous experience with the medium, may feel excluded or discovered since they don’t have a thorough comprehension of it. To illustrate, in the case of video games, digital literacy and minimal involvement in the digital world are required. Individuals who are not very familiar with video games might feel alienated when they try to interact with a game’s interface and controls. For example, games like “Dark Souls” and “Elden Ring” are recognised for their high level of difficulty, which might turn off gamers like me who want to appreciate the art but prefer more accessible gameplay experiences. Exploring further, artists may have to prioritise particular aspects of their work and ignore others because of any inherent limitations and distinctive features of a medium. A big compromise is made in terms of narrative depth when it comes to VR which prioritises the immersion and sensory aspects of a simulation. This can result in the disappearance of the traditional aspect of storytelling, as viewers are more inclined to explore and engage with the environment instead (Klassen, 2015). And since VR requires high optimisation levels, compromises may also need to be made when it comes to the quality of graphics. Additionally, other types of medium specificity like interactive street art installations can urge spectators to actively participate even when the viewers would rather be involved in a more passive manner. Picture an artist that builds an interactive street project in a public square by using movement-sensitive objects that produce loud and sudden sounds on trigger. While this can result in an immersive and engaging experience for some, it can also have an intrusive or demanding tone for others. Pedestrians just passing through the area might accidentally activate the art installation, which leads to unwanted and disruptive interactions. This not-so-agreeable aspect of medium specificity makes me question the idea of consent and the limit to public engagement. Many individuals might feel discomfort or a sense of obligation if they do not feel like interacting. This changes the Dynamics of the link between viewer and artwork greatly, as the line between active engagement and passive observation becomes blurred out.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Sources

McLuhan M., 2005. Marshall McLuhan Understanding Media The extensions of man. [pdf] Available at: https://designopendata.files.wordpress.com/2014/05/understanding-media-mcluhan.pdf. [Accessed 22 Oct 2023]

Krishna S., 2022. "‘Elden Ring’ Isn’t Made for All Gamers. I Wish It Were". Culture. [e-journal]. Available at: https://www.wired.com/story/elden-ring-difficulty-modes/. [Accessed 22 Oct 2023]

Lewis M., 2021. Phantasmagoria and the earliest forms of horror storytelling. Stories & Ideas. Available at: https://www.acmi.net.au/stories-and-ideas/phantasmagoria-and-earliest-forms-horror-storytelling/. [Accessed 22 Oct 2023]

Klassen E., 2015. Active Story: How Virtual Reality is Changing Narratives. [online] CableLabs. Available at: https://www.cablelabs.com/blog/active-story-how-virtual-reality-is-changing-narratives. [Accessed 22 Oct 2023]

0 notes

Text

Blog Post 2: Tools

youtube

For this blog, I have chosen a project of my own to analyse and evaluate in relation to the two concepts of Gesamtkunstwerk and medium specificity. In order to do that, I will first need to dissect my analysis into three different key points of study, so that I am eventually able to make a link between my work and the two main concepts:

What is special about my medium?

How is it connected to other types of media?