Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

The Goldilocks Zone: Pareto-superior asset-swapping

Men did not love Rome because she was great. She was great because they had loved her. Gilbert K. Chesterton, Orthodoxy, 1908

Capital markets in peacetime left to their own devices are simply not poised to build infrastructure at scale in the absence of Hamiltonian dirigisme. Should risk-premiums be prohibitively high to hedge against it is then incumbent on government to be a de facto developmental bank: a prerequisite to any species of serious industrialization. The Transcontinental Railroad made flesh by statecraft thus conscripted private firms in service to a public good. The animal spirits of laissez-faire capitalism alone could never be a prime mover of such ambition. Ergo state paternalism must seed the prototype of industry and retreat upon the latter’s maturation. Indeed America’s proper Industrial Revolution was a function of this largesse between, inter alia, chartered companies, land grants, postal contracts and military procurement. What became of the subsidization of railroads was the wholesale replacement of an ancien régime defined by loose markets. Not only would Congress see to the construction but it would also wed this technology to a novelty in communication: those electrical signals of dots and dashes eponymously named after inventor Samuel Morse. Telegraphy thereby entered a symbiotic relationship with locomotives. Poles and overhead wires sunk into rail beds would mark the advent of the Gilded Age.

The value proposition of packet-boats and pony-express couriers regressed into an anachronism upon telegraphy’s emergence. Information latency once commonplace became a relic of the past in the wake of realtime messages. Whilst the 1862 Pacific Railway Act enshrined by statute that railroads and telegraphy be built in tandem there did exist ex ante precedent for merging the two together. This saga harkens back to when Samuel Morse petitioned 30k USD (1.2m in constant dollars) from Washington for a proof-of-concept two decades prior. In 1843 Congress appropriated the said subsidy for Morse’s telegraphy experiment with two sui generis provisos: a) the wire must follow Baltimore & Ohio Railroad’s right-of-way easement; b) upon success any priority access thereafter would be conferred to government telegram dispatches. Congress parted with coin from its purse to court innovation whose breakthrough later opened a portal to continental integration. Lawmakers sued for use of the railroad between Washington and Baltimore as a laboratory since the ready-made infrastructure commons was already graded for such an experiment. As a result of pure utilitarianism the B&O minimized capital and marginal costs to inaugurate a maiden message of Bible origin ‘What hath God wrought’ over the wire (Howe 2007). A halcyon era began in earnest.

Deadweight loss from information asymmetry was ended with the marriage of iron and copper. Railroads and telegraphy soon proxied for America’s nervous system which gave credence to Metcalfe’s Law: that the dividends from this industrial policy increased commensurately with the growing number of users in this new network. The social and economic returns therefrom were aplenty. Behind such statecraft lay the genius of its high-externality investment of modest means to galvanize private capital en masse. From an acorn grew a forest. Rather than nationalize telegraphy like Whitehall did at the mercy of its leviathan of a bureaucracy in London it was decided by Washington that a market strategy would fare better (Perry 1997: 416). Congress pump-primed an entire industry and allowed private investors and their speculation to scale up the result. A Pareto-superior outcome was had. The minimalism here of abstaining from public ownership would be the catalyst to discovery and innovation. The difference in philosophies is stark: Britain’s mandarins haemorrhaged funds whereas the discipline of capital markets in America expedited commercial infrastructure. Such a development model wherein telegraph entrepreneurs rode the coattails of railroad land grants was what spurred industrialization.

This doctrine of oblique intervention by government mitigated risk in new markets for captains of industry to be seduced into speculation. America’s Goldilocks zone in its state paternalism was enough to be a fiscal multiplier for large-scale investment in railroads and telegraphy bereft of any massive public debt: not too little, not too much, but just the right amount of industrial policy ensured the parsimony of not having pork-barrel waste to the benefit of a few monied interests. Therefrom the provision of land and some seed capital revolutionized supply-chain logistics to feed the factories and furnaces of a fledgeling empire. The potent combination of government and investor discipline was a prophylactic against any rent-seeking moral hazard where risk might be fully socialized as in bailouts. Any loose resemblance to Crown monopolies was therefore anathema to Congress for good reason since the latter’s industrial output languished over time. America’s industrialization came to hinge on the adventurism of businesses within the parameters and guardrails provided by Congress. This early species of public-private partnerships avant la lettre proved instrumental since onerous taxes would not be levied on the public for critical infrastructure of national importance.

Citizens were spared the eye-watering expenses of nation-building under this model of industrial policy. Budgetary debates and their inflationary finance were sidestepped with asset swaps: public land in exchange for a few telegraph poles and railway sleepers. Such a quid pro quo in the company of a modest subsidy was emphatically the sine quo non of this Industrial Revolution. Asset-swapping built America! The most austere version of development saw idle resources like prairies traded for infrastructure. Assets of differing maturities and risk profiles were then swapped for each other. That iconoclasm not seen in Europe eliminated moral hazard since land grants were predicated on specified benchmarks throughout the lead time in construction. Were federal cash used alone to subsidize such vast infrastructure without the miscellany of other incentives the nation would have been torn asunder by bankruptcy. Instead the non-monetary asset of land underwrote the fixed capital of tracks, stations, poles and wires to transform America into a single market. A Pareto-superior outcome delivered: a) preferential rates of telegraphy and carriage to Congress; b) social returns on investment for the many; c) riches for railroaders and companies like Western Union. Nowhere was this industrial policy replicated: shareholders rather than taxpayers industrialized a nation.

0 notes

Text

Factor Mobility: New Economic Geography Theory and Icebergs

The blood of the heroes is closer to God than the ink of the philosophers and the prayers of the faithful. Julius Evola, Revolt Against the Modern World, 1934

The philosophical wellspring for the Pacific Railroad Act of 1862 was anything but an article of faith as big and small government proponents were hostile to each other. Were it not for the loss of veto power of the Jeffersonian South upon the Confederacy’s secession in 1860 it is certain the Transcontinental Railroad would have floundered. The federal government’s industrial policy was the vanguard of this infrastructure bereft of which the private sector would have spurned participation. State paternalism reached an entirely new watermark of efficacy through its horse-trading with the private sector to birth this public good. The abundant factors of production between public land and private capital were masterfully exploited to be springboards of industry. In the midst of bloody conflict with the outbreak of Civil War this feat of policy brought together a vast continent. The use of land grants were of particular note. By parceling out plots in a mosaic pattern to the dual franchises of the Union Pacific and Central Pacific companies a monopoly of transportation and real estate was established. Both companies became gatekeepers to industry and population as the mobility of goods grew commensurately with frontier homesteaders. Rather than be subject to the capture by bureaucracy America’s empire was delegated to business buccaneers so it may be actualized within an abbreviated timeline.

The Gilded Age was the child of this 1,776 miles of track. Above all limiting factors to productivity it was transportation costs which eroded profit margins most acutely. Thus infrastructural deficits had to be remedied first and foremost as a prerequisite to industrialization. Factor mobility then is the single most salient variable to affluence. Infrastructure meant to expedite the movement of capital and labour with minimal friction is the surest way to expand the production possibility frontier and create wealth. Since time immemorial the logistics of such supply chains have been a bellwether for civilization. Empires of old were therefore always keen to invest in maritime trade or roads for merchants. Factor mobility is thus directly correlated to the efficiency of resources. And just like Economist William Stanley Jevons famously observed the more something is used efficiently the more consumption of that said resource will be. To wit, this principle informs steel manufacturers whose revolutionary Bessemer process stimulated consumption other than for railroads as cost reductions prompted the technology’s adoption in construction. Higher efficiency equates with greater output not less — Jevon’s Paradox. Hence America’s economic miracle stemmed from lower prices buoying up demand courtesy of critical infrastructure.

By the eve of the Civil War the application of railroads were by no means a novelty when short-lines dotted American pastures. What did differentiate the Transcontinental Railroad however was its scale. The tyranny of distance had perennially been a scourge on commerce — an entry barrier to markets. Washington redressed this fragmentation. What ensued was a wholesale reorganization of economic life. Economist Paul Krugman (1992) in his New Economic Geography theory (NEG) would expound how the Pacific Railroad Act exerted a centripetal force on major commercial centres. The advent of this infrastructure prompted businesses to gravitate towards particular nodes of industry in tight clusters to reap economies of agglomeration. Companies backpedaled on being widely dispersed to concentrate themselves so they may produce at scale more gainfully in concert with one another. Shrinking time and space lowered transportation costs to incentivize greater production and capital into homogeneous havens where likeminded businesses proliferated: close proximity cross-fertilized know-how. Case in point, between 1870 and 1890 Chicago’s population soared 268 percent from thirty thousand denizens to over a million. A once humdrum outpost matured into a teeming metropolis of industry.

Greater factor mobility lends itself to capital formation whereby industries plough higher profits into rationalizing production so they may in time scale up output. Economist Paul Samuelson (1954:268) analogized this phenomenon quite brilliantly in his ‘Iceberg Cost’ model for trade. This iceberg is an avatar for any generic good that is shipped. Distance or time thereof are the real bogeys problematizing such transportation. The longer the trip, the more the iceberg melts prior to reaching its final destination as value depreciates. By extrapolation the same dilemma afflicts goods that must travel afar. If transportation costs exceed the value of the shipment itself then it is illogical to trade. A quid pro quo of this nature between buyer and seller would not be one of capitalism but rather of charity — giving away things for free at one’s own expense. Any merchant of sound mind would be deterred from a money-losing venture of this kind. If the friction of distance across the hinterland is too onerous then a shrewd business will refuse to partake in it. Hence the reason for the torpor of industry before the Pacific Railway Act of 1862 since the right infrastructure had yet to be conceived. Wagon caravans or steamships of old failed to make the cost-benefit ratio of long-distance commerce favourable to monied interests.

As a matter of fact, mail subsidies were ubiquitous for over a century just to artificially create markets for transportation where none existed. The Postmaster General first patronized overland stagecoach lines whose services could accommodate the delivery of parcels. Packet lines of steamships were next to be made viable by the regular revenue from government largesse. The solvency of these companies and their routes were guaranteed by this influx of capital. Even amidst the nascent era of railroads the operators were party to a baseline income for mail carriage. A dependable traffic base would fund tangible assets for companies to ferry evermore greater numbers of packages and people to faraway places. But these ameliorations in logistics were too minor to disrupt the status quo of isolation that arrested interstate commerce. Trade at scale was moribund in the absence of the right infrastructure. In the main the problem echoed Samuelson’s Iceberg Model whereby any profit was cannibalized by the transportation cost or more figuratively the iceberg would melt on route. No value inhered in long-distance trade. Until the introduction of railroads the disincentive of distance made America’s backwardness a foregone conclusion. The industrial policy of the Pacific Railway Act of 1862 would be an inflection point.

0 notes

Text

The Civil War's Black Swan

The dogmas of the quiet past are inadequate to the stormy present. The occasion is piled high with difficulty, and we must rise with the occasion. Abraham Lincoln, Annual Message to Congress, 1862

The nerve centre for the Industrial Revolution would be the Transcontinental Railroad which barrelled through miles upon miles of unsettled territory after its completion in 1869. Inspiration for this infrastructure was twofold: (i) tether the Pacific shores into the bosom of national unity; (ii) stimulate heavy industry with its many spin-offs downstream. The wilds of the Great Plains thereafter were terraformed into farmlands and a paradise for millions of hardy settlers. Volumes of interstate trade crested to new heights as frontier outposts transformed into cynosures of business. Consolidation of a continent manifested in tandem with the territorial aggrandizement afoot between the Louisiana Purchase (1803), Texas’ annexation (1845) and Mexican Cession (1848). The short-line railroads scattered about the Northeast became the ideal muse for the federal government’s adventurism in the unification of these vast tracts of land. One major pillar of protest had to be quashed however — the South. Southern Democrats balked at a lateral railroad up north for fear it would create an apartheid of wealth against their cotton agrarianism. As differences turned toxic a bandwagon of states seceded under the Confederacy beginning in 1860 thus Washington’s balance of power shifted in favour of Republicans.

With a major bloc of opposition in exile this vacancy bestowed a carte blanche for Republicans to be the architects of an American renaissance. Endless deadlock over the proposed route became a footnote once control of both legislative chambers in Congress were seized by votaries of this new infrastructure. Legislative assent would be given amidst the throes of the Civil War in 1862. The genesis of the railroad was anything but bipartisan. In the absence of a splintered government the Senate approved the project 35 to 5 and the House of Representatives followed suit 104 to 21. With President Lincoln’s acquiescence by signature a whole army of likeminded lawmakers busied themselves to mobilize the capital and labour for this feat of de jure construction. This symbolic victory of binding California’s material wealth to the Union gave credence to the legitimacy of the North and its continuity. The latter could lay claim to the true guardianship of progress despite the holdouts when stagecoaches, wagon convoys and ships circumnavigating the Cape Horn would become obsolete. The law was a masterclass of realpolitik. America’s Manifest Destiny was on the verge of realization since fortune-seekers could migrate west with dispatch. If the interregnum of secession had not occurred the railroad would be stillborn.

The pro-business leanings of the Yankees codified in the Pacific Railway Act of 1862 was a fait accompli of American empire. The Industrial Revolution continued apace. This infrastructure sprawling the inhospitable Sierra Nevada over the Great Basin and Great Plains would establish two discrete companies: (i) the Union Pacific Railroad which oversaw the eastern segment from Omaha, Nebraska; (ii) the Central Pacific Railroad which occupied itself with the western leg from Sacramento, California. Such bilateral construction meant both companies would meet halfway at Promontory Summit in Utah. Provisions in this Act were quite inventive: ten land grants of 6,400 acres or one-square-mile each on alternating sides of the railway akin to a chessboard was gifted for every mile of track laid; government bonds were issued for every 20-mile section of track (Klein 2019:24). Railroad companies availed themselves of the first stipulation to have settlers and businesses buy or lease the land adjacent to their tracks for raising capital. Future revenue was also guaranteed since these communities would be subservient to the utility of railroads for goods and people. The second provision of bonds enabled the two companies to layer their capital structure with loans sponsored by the full weight of the federal government.

These thirty-year bonds at 6 percent interest were released in tranches to the Union Pacific and Central Pacific railroads for every mile of track laid to incentivize speed in the infrastructure’s lead time (White 2011). The opulence of these tranches hewed to terrain difficulty. The sum of $16,000 per mile was unlocked for the plains, another $32,000 for the Rocky Mountains and $48,000 for the Sierra Nevada range. Washington was an intermediary in these bonds which reassured investors and railroaders alike as the risk profile of this enterprise would be borne by the treasury to reduce market imperfections. Over the construction’s lifetime these capital infusions approached $65 million (Uschan 2009). But deadlines and benchmarks were enshrined in the Pacific Railroad Act to deter any slipshod work with the forfeiture of privileges at stake. Such structure of incentives and disincentives truncated the gestation of the Transcontinental Railroad to less than seven years between its ribbon cutting and completion. Market failures abound for any project of this scale which tends to attract unsavoury characters with rent-seeking cupidity. But the federal government’s industrial policy did mitigate the excesses of capitalism from sabotaging infrastructure that reduced cost-to-coast mobility from months to a week.

The Pacific Railroad Act with its unique blend of property rights and fiscal ingenuity might be likened to a work of art. A perfect instrument was introduced to make manifest what was otherwise a unicorn of an idea. Companies were entrusted with prime real estate to mortgage or sell across a patchwork of private land interspersed between public ones so the government could also reap value from this corridor at the backend. Subsequently property value soared from speculation. The Union Pacific and Central Pacific Railroad companies were also less skittish about amortizing their liabilities courtesy of the front-loaded financing from homesteaders who purchased their lands. These generous grants were not some negligible perquisite but rather invaluable to recoup costs before train traffic had matured. Early settlers were then initial guarantors of the railway’s solvency prior to the scale economies from every extra mile of track accessing additional government bonds. Ergo land grants jumpstarted operations and loans predicated on miles sustained them; each promised the influx of capital. Over twenty million acres of public land and $60 million in bonds would be dispersed between the Union Pacific and Central Pacific Railroads (Bain 2000:128). This unique quasi-public plan militated against inertia in the project.

0 notes

Text

The Tenth Amendment: A Trickle-Up Developmental State

The coming of the railroad was the death knell of the old frontier. Frederick Jackson Turner, The Significance of the Frontier in American History, 1893

Already dispelled is the fallacy that America’s railroads were the sole preserve of men with private means since Washington’s industrial policy was the vanguard of this sprawling infrastructure. There was more at work than just rugged individualism. The young Republic’s fixation on ‘internal improvements’ predated locomotives as the government was already the benefactor of canals, roads and the like. Hitherto waterways were the darling of subsidies only because the locomotive had yet to be invented until the Erie Canal’s inauguration in 1825. But the adoption of this new technology from England occurred posthaste. The embryo of railroads was first conceived in the lower tiers of the federal system where the impetus to such infrastructure resided with state and local governments. The Maryland General Assembly was the first to enact a charter officially sanctioning a railroad between its port city of Baltimore and the Ohio River after its anxiety over losing the race for westward expansion. Provisions therein included the right for municipalities to be substantial stakeholders in the newly formed company should they choose. This business interest was also bestowed eminent domain rights to veto holdouts in its acquisition of land (Dilts 1996).

The charter established 30,000 shares in the company valued at $100 apiece. Maryland became a vested interest with an equity of 10,000 shares; the city of Baltimore reserved 5,000 shares (Stover 1987:17). Thereafter the remainder of capital was raised from merchants and financiers alike. Half of the financial scaffolding for America’s first railroad therefore emanated from legislative bodies. Private investors were then raring to invest based upon such asymmetric risk. In effect public ownership at any scale hedges against losses or failure for the quorum of shareholders in question. Whether intended or not, whenever a company’s investment becomes quasi-public it can automatically be considered a de facto monopoly. Government bristles at the idea of competing interests upsetting its stake in that said company and will thus preserve its marketshare at all cost in this public-private partnership. Although ethically dubious the practice of privatizing profits and socializing risk often yields great prosperity in a positive-sum game. For the city of Baltimore the solvency of the B&O Railroad venture was itself an existential imperative. Further to the south the city of Washington D.C. enjoyed a head start to secure business for its port of Georgetown by chartering the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal (C&O).

This new waterway between the Potomac River and Ohio presaged the diversion of trade away from Baltimore. In response the B&O would be Baltimore’s gambit to safeguard the city’s future primacy when the proven technology of canals were well known to create wealth and jobs. The railroad’s construction was a canal-adjacent investment to stave off the spectre of economic irrelevance. Although partisan dissent did oppose the idea of underwriting massive debt on behalf of a private company the rich dividends were not so easily dismissed. A windfall accompanied Baltimore’s unbridled access to America’s interior from the traffic of agricultural commodities like grain, tobacco and pork. The fusion of public and private interests by the coalition of railroad boosters bestirred the latent forces of production as this iron link reconciled Baltimore to the Ohio valley. Years later this industrial policy offered a blueprint espoused by the federal government in founding the Transcontinental Railroad. The saga of the B&O Railroad charter really is a case study of industrial policy avant la lettre. Prior infrastructure in the likes of canals, ports or lighthouses came to fruition from subsidies in contractual form by tender. The B&O separately materialized as a sui generis venture: half public utility; half private company.

State and municipal legislatures both held equity in a corporate charter which was itself an aberration. This novelty broke with tradition of passive investment by placing government at material risk in an otherwise speculative pursuit. No precedent existed hitherto whereby the public treasury was a vested interest alongside private shareholders. Over a century later the staying power of this practice would be seen in the bailouts of distressed companies like Eastern Airlines, Alaska Airlines, Chrysler or General Motors. But otherwise no ex ante reference could be consulted at the time to expound the agency of government taking a direct stake in a company deemed critical for the commonwealth. So whilst both Maryland and Baltimore were adamant on preserving their place in the national supply-chain they were equally seduced by the dividends for their electorate. Micromanagement of a company thereby substituted for the more aloof method of soliciting contract bids which were common for mail routes. But ephemeral subsidies like the foregoing did not confer the same control as the quasi-nationalization of a company. Such a hybrid structure in ownership of public investment in corporate equity acutely differed from the state-owned model of public works whose costs were recouped by tolls.

An outright purchase of stocks was the polar opposite to service contracts awarded to independent companies which were au fond government proxies entrusted with public monies. Collaboration in those days never included any semblance of equity participation. Indeed canals and turnpikes were funded by state treasuries; postal subsidies would separately spur pan-American or transcontinental routes for commerce. Instead the B&O railroad experimented with a novel instrument to hasten the realization of this public good for transportation by allying public with business interests. The real causality for this innovation can be readily discerned. Maryland and Baltimore were hard-pressed by the spectre of New York’s Erie Canal and the legislative assent for the C&O Canal in 1825. Without a swift correction both the state and city would be fated to be marginalized from trade altogether. It was incumbent on the two to stake their future on a new form of infrastructure. Hence the B&O railroad evolved into a microcosm for a new variant of industrial policy to mobilize functionaries and financiers alike in the first partnership of its kind. Not long after did this mixed model gain currency as Cincinnati acquired the Little Miami Railroad (Hedeen 2021) or Kentucky and its state capital of Lexington exercised part ownership of the Lexington-Frankfort Railroad (Boyd 1964:6).

In time this atomized version of industrial policy for railroads trickled upward to the federal level. The logic behind this statecraft being first under the financial wizardry of state and local governments derived from the Constitution’s Tenth Amendment. Any enumerated powers not explicitly reserved for Washington were delegated to states and municipalities. This omission of plenary authority and its constitutional exegesis still divides Congress to this day. The descendants of Hamiltonian and Jeffersonian schools of thought have long been at cross-purposes over this third-rail of an issue: Alexander Hamilton extolled centralization; Thomas Jefferson adhered to devolution. This feud saw that the federal government directly intervened in markets very seldom. Only twice heretofore had elected leaders sought to correct markets with the Federal Lighthouse Act of 1798 to finance the guardrails for navigation and the Federal-Aid Road Act of 1806 to build the Cumberland Road. So whilst the federal government showed a reticence about its mandate a vacuum was filled by the prerogatives of states. The Tenth Amendment was no dead letter and the fear of the Supreme Court’s policing anesthetized infrastructure at scale for the republic. It was President Abraham Lincoln who would later become the first contrarian.

0 notes

Text

Happy Spillovers: Sperm Whale Oil Displaced by Petroleum

The introduction of so powerful an agent as steam to a carriage on wheels will make a great change in the situation of man. Thomas Jefferson, 1802

Railroads were not only a moment of inflection for the steel empire but they equally wrought downstream effects for petroleum by opening America’s interior to industry and speculation. If this new infrastructure coronated Carnegie as the king of steel then it did the same for John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil company. Legislation behind the railway boom made this commodity viable for commercial use since extraction, refining and distribution could be scaled up when heretofore waterways limited production to modest quantities. The alacrity of this energy revolution is startling. A paradigm shift of logistics made the whale oil industry redundant overnight. Prior to the railroad mania transportation prices were dearer than any amount of petroleum whose exploitation was itself too labour-intensive and confined to seeps and shallow excavations atop the earth's surface. Hence whale oil’s omnipresence in the economy for lighting and other uses. By providence however Edwin Drake’s first oil strike via his innovation of drills and steam engine in 1859 perfectly coincided with the heyday of railroad construction. This infrastructure was a godsend. Petroleum could suddenly be monetized. A spate of oilfields came online from Ohio to Texas and brought the hydrocarbon to consumer markets as this black gold increasingly rose to prominence.

The genius behind Rockefeller’s alliance to railroads hinged on preferential treatment in a reciprocity based upon steady shipments in exchange for steep discounts. Investors and owners alike took warmly to this guarantee of revenue. No rival could subsequently compete with the conglomerate without operating at a loss since they were saddled with higher freight costs. A raft of bankruptcies then ensued. Rockefeller in turn practiced vulture capitalism through his aggressive acquisitions of companies in distress upon pricing them out of markets. An empire was consolidated piecemeal whereby railroad mania conduced to the oil boom: monopolies created ever more monopolies. Detractors might tar and feather Washington’s succour which privatized gains and socialized risk for railroad barons but there is no ambiguity how a better standard of living summarily followed. Prior to the advent of petroleum the rendered fat of whales had a purchase on artificial lighting in parlours and homes everywhere. Kerosene abruptly displaced the latter as a cheaper fuel of choice for the mundane chores of heating, cooking and the like. The ascendency of oil thus disrupted the whaling trade. Washington’s industrial policy for railroads so became a stimulus-cum-revolution against industries of old which were anachronisms of modernity.

The creative destruction of petroleum-based fuels toppled the whaling stranglehold. Railroad mania abreast of the oil rush would herald the beginnings of the Gilded Age. Why was the boom so immediate? One glaring pitfall of the whaling industry was its vulnerability to supply shocks. Just as Herman Melville chronicled in his chef-d’oeuvre ‘Moby Dick’, whalers voyaged further and further out to sea for months if not years in their expeditions as diminishing returns were symptomatic of fewer and fewer whaling grounds. To this very day numerous species of whale remain on the brink of extinction as a corollary to this systemic culling. Consumers therefore embraced petroleum en masse. Railroads were not tangential but central to this demand shock wherein petroleum evolved into a universal staple for households and businesses. Social and economic activities extended their hours well into the night unbothered by neither the cost nor scarcity of artificial light. As the star of the whaling industry faded, the use of petroleum continued to collect marketshare and mindshare in the last quarter of the 19th century. Energy consumption would be dominated by petroleum in lockstep with the expansion of railroads. The scalability of kerosene unlike the scarcity of whale oil was the death knell for the Atlantic seaboard’s whaling industry.

Scale economies were simply a chimera for whalers when they were destined to wrestle these sea monsters in the open waters as far away as the Arctic or past the equator into South America. Compare this labour-intensive enterprise with the capital-intensive one of boring a rudimentary hole into the earth and pumping fresh crude out of it. Such abundant supply and cheap distribution by railroads were infinitely preferable to multiyear voyages fraught with hazards. Petroleum reserves were seemingly inexhaustible with the discovery of oilfields via onshore drilling by wildcatters. Whale oil was finite. Electricity generation was likewise an adversary which posed an existential threat to the whaling industry as Thomas Edison patented the incandescent lightbulb in 1880 (Scirri 2019: 41). By the end of the 19th century the commercial whaling industry was beset on all sides by competition which proved insurmountable. Capital destined for the harbours of New England where fleets of hundreds once moored found greater returns on investment in petroleum. This transformation became a parable of the ‘creative destruction’ of capitalism’s lifecycle between the obsolescence of an industry and the birth of another. Shipwrecks, mutinies and erratic whale migration simply could not compete with the ironclad certainty of oil.

Petroleum and steel would develop along similar pathways in their ascendency. Namely both industries were critical agents for the buildout of railways in what can be construed as a positive-sum game: (i) oil relied on locomotives for coast-to-coast distribution; (ii) steel sought railroads for the demand of tracks; (iii) railroads vied for the inelastic revenue from oil freight; (iv) railroads equally required steel. Each industry had mutual interests as they jockeyed for favourable terms. The exploits of Rockefeller and Carnegie were also identical in their strategies of horizontal and vertical integration within their respective industries. Standard Oil would seize every stage of the commodity’s life cycle by vertically integrating pipelines, refineries and oilfields. US Steel implemented the same strategy with its acquisitions of mines, lake barges and rolling mills to reduce the volatility of its market. Both entrepreneurs conquered value chains whose economies of integration purveyed a cost advantage which was passed onto consumers. Another likeness was the scale of horizontal integration shared between the two. Rockefeller swooped in to buy competitors in distress. Carnegie consolidated his steel empire in a selfsame fashion. In business lore the legacies of these storied companies share an uncanny resemblance.

0 notes

Text

Kingmakers: The Oligopsony of a Monopoly

The railroads are not run for the benefit of the dear public. That cry is all nonsense. They are built for men who invest their money and expect to get a fair percentage on the same. William Henry Vanderbilt, 1882

Prior to the railway boom American ironworks were beleaguered by sluggish growth. Demand by this new infrastructure however quickly distorted markets in favour of these foundries as iron and steel were sold at prices and volumes underwritten by government. How pregnant was this moment? At the outset of the 20th century upon J.P. Morgan’s consolidation of steel acquisitions the market capitalization of his new entity called U.S. Steel was the first to exceed a billion dollars in human history (Hessen 1972). The railroad monopoly became a de facto oligopsony for the vast consumption of durable metals between rails, rolling stock and bridges. In Washington’s economic arms race with Britain the government’s legislative capture gave rise to a captive market for these same manufactures. A staggering 90 percent of all Bessemer steel made in America between 1870 and 1890 flowed directly towards locomotives and their trappings (Misa 1998). The epithet of kingmaker aptly describes the clout shared by barons like Vanderbilt or Gould who themselves deputized steel magnates like Carnegie. The great blast furnaces of the Northeast were creatures of the railroads. The direct pipeline between the two conduced to the scale economies required for the exponential growth of each.

Yet something far more unique other than capital formation manifested in the symbiosis of both industries. Borne out of this marriage came a series of innovations in metallurgy due to the exigencies of railroads. Necessity is the mother of invention and ironmongers were tasked to create a material which would not succumb to the forces of attrition by the frequency and weight of locomotives. The industry thus espoused Darwinism whereby only the strongest metal survived whose properties demonstrated fewer and fewer impurities with each iteration. The first alternative of cast-iron exhibited a failure rate prohibitively high which risked frequent derailment. This iteration befit stationary loads akin to bridges but was too brittle for the stress tolerances of rails. Microcracks symptomatic of metal fatigue called for greater investment in the search for superior iron alloys with a greater lifespan. The next metal of choice to withstand the cyclical stresses of locomotives would be wrought iron known for its improved tensile strength. Yet despite its longevity this metal was also prone to fracture to the consternation of engineers. Recurrent failures spoke to the need to find more robust materials. The next quantum leap in technology was the introduction of puddled iron whose production method controlled for oxidation.

Despite this breakthrough being lightyears ahead of the pig iron of yesteryear it still remained an interim solution since it was liable to wear prematurely. The labour-intensive nature of this metal in its artisanal process meant quality irregularities continued to beset the service life of rails. Such limitations were anathema to the overhead of maintenance for railroad companies which sought to escape these recurring costs. Puddled iron therefore would be a stopgap until a final iteration materialized. Unlike its predecessors the technology of Bessemer steel won the hearts and minds of builders and financiers alike since its automation yielded consistent results. A controlled blast of air through an apparatus called a Bessemer converter produced high-quality grade metal at scale without fail. The pursuit of perfection thereby culminated in the mass production of steel which was well-nigh immune to fatigue from the rolling contact of locomotives. Railroads embraced this new technology with vim and verve as its removal of impurities within minutes generated greater output at less cost. A material upgrade of this sort saw this alloy become the sine quo non of railway construction to universal acclaim. Indeed America’s Industrial Revolution was essentially the legacy of Bessemer steel (Peters 1945).

Railroads were proving grounds for innovation in a race to source the best materials. New technologies in the production of alloys were not made in a vacuum but were functions of a pent-up demand for high-quality rails. The learning-by-doing of various foundries inexorably led to the apogee of Bessemer steel which was the gateway to industrialization. But no other industrialist exploited the captive market for rails more deftly than Andrew Carnegie who vertically integrated his operations to consolidate supply chains. His broad acquisitions of coal mines, iron fields and limestone quarries enabled a seamless transit of raw goods to their final destinations for steelmaking. As soon as Carnegie wedded such vertical integration to the Bessemer process he devastated his competitors with aggressive pricing. The brilliance of this market strategy can be laid bare as thus: the steel baron enriched himself by recouping his margins on the backend of procurement deals based on volume. Carnegie then shaped the purchasing behaviour of railroad companies with discounts in return for volume lest they forfeit premiums for the same product at other manufacturers. Always the shrewd negotiator, Carnegie cornered the market in a mutually beneficial alliance with railroad barons whose oligopsony created a monopoly within the steel industry.

The incestuousness between Carnegie and the railroad industry has no better proof than how his largest mill was a namesake for the president of the Pennsylvania Railroad. The Edgar Thomson Works founded in 1875 near Pittsburgh is eponymously named after the man. What differentiated Carnegie from his rivals was how he dared to capture the business of every major railroad company by creating an empire impervious to the price fluctuations of intermediate goods. What resulted was a closed-loop supply-chain to the detriment of competition. Such centralized control meant ore was sourced in Carnegie’s mines which was transported on his barges or trains which in turn was smelted in his mills. Absolute authority over the entire value chain of steel was the impetus behind the vast fortunes amassed. Carnegie was equally averse to the golden standard of business: diversification. Steel rails were a singular focus unlike other competitors vying for contracts to manufacture naval warships and castings. This specialization and the scale economies thereof locked out any other supplier in the hunt for marketshare. Corporate diplomacy was also an idiosyncrasy unique to the steel baron as he exploited philanthropy to court business like inaugurating the Carnegie Library of Homstead in the hometown of railroad executive William Donner.

0 notes

Text

A Cambrian Explosion: Friedrich List versus Adam Smith

God Almighty Himself must have been hilarious when human beings so mingled iron and water and fire as to make a railroad train! Kurt Vonnegut, Bluebeard, 1987

By the twilight of the 19th century no other industry parlayed Washington’s protectionism into a triumph of scale more so than the steel industry. In the wake of a ready market immune to uncertainty, predicated upon the demand for rails, ironworks were poised to mount mass production bereft of any undue fear of idle capacity. Owners felt bullish about expansion and innovation within the parameters of knowing their enterprise would be fully backed by government. Herein a universal theme of incentives can be gleaned in America’s industrialization: the canonical role of government was to reduce risk for business mavericks to invent in their sandbox unfettered by the spectre of loss or regulation until their niche industry became a national one. A heavy hand thus created a domestic market amiable to downstream development under the auspices of government. Provide the fertile ground and all sorts of flora will flower. Heavy industries were then beholden to the paternalism of policymakers. The railroad with its many protections and privileges epitomized a laboratory for industrial expansion. Nearly all of iron and steel consumption fed these locomotives and their grids (Swank 1892:426). The correlation therefore between railroads and industrialization was not at all casual but causal: by the end of century homemade metal blanketed the nation.

The genius of the strategy lay uniquely in the marriage of subsidies and tariffs. The idea was to create a garden and corral it behind disincentives for imports to keep foreign producers at bay. Washington would be the gatekeeper. Aversion to competition from European producers long troubled lawmakers in the post-Revolution period after the War of Independence in 1783. At the crux of this unease was how established manufacturers threatened domestic industries with cheaper capital and consumer goods which would be anathema to industrial growth at home. The corporate welfare of shielding import-competing businesses against such predations was nothing less than an existential matter. Over a longer time horizon the short-term sacrifice of paying a premium for domestic goods would yield long-term gains as smaller companies scaled up their businesses with a pro tanto fall in prices. Economist Friedrich List (1841) in his seminal treatise denominated this phenomenon of dirigisme the ‘infant industry’ theory. Insulate a fledgling company and in less than a generation it will be the envy of global markets. Such a captive market allowed America’s manufacturers to surpass English cities like Birmingham and Sheffield when they were inoculated against the winds of competition from abroad.

List’s ‘infant industry’ theory was an indictment against the universalism of free trade fathered by Economist Adam Smith (1776). In the context of the modus vivendi after the War of 1812, America adhered to the tenets of the former in its bid to rival the Goliaths of European industry because it could scarcely compete otherwise. The economic saga is quite lively. Upon the normalization of trade relations anew Britain sought to recapture its prewar marketshare by dumping its glut of goods which were denied during the internecine conflict. Domestic producers soon reeled from the loss of their foothold in the marketplace. So began the age of tariffs at the behest of homegrown industry. A whole battery of duties followed with each act more intense than the last: the Tariff of 1816; the Tariff of 1824; the Tariff of 1828 or colloquially dubbed the ‘Tariff of Abominations’; the Morrill Acts of 1862 and 1864; the McKinley Tariff of 1890; the Dingley Tariff of 1897. Prohibitive levies as high as 100 percent on manufactures defied Atlanticism. Ironically enough as List’s economic nationalism was made flesh in Washington, London sued for Smith’s thesis of free trade instead by its repeal of the Corn Laws in 1846. One nation repudiated classical orthodoxy whilst the other embraced it — but only after having wed itself to the same statism which enriched it for so long.

America vindicated List’s doctrine with its industrial catch-up to Britain at meteoric speed. Business interests, well ensconced behind tariff walls, fought well to capture scale economies and technologies that were once elusive in the absence of high levies and infrastructure like railroads. A sheltered market and superior logistics were prerequisites for businesses to move up the value chain whose result shattered the illusion of English invincibility in industry (Irwin 2017). It is not reductive to argue America’s ascendency was monocausal: industrial policy was the thrust behind most if not all of it. In the end America would no longer be marginalized as the feedstock of empire but instead become one. Suddenly a Cambrian explosion manifested. Sourced in the crucible of economic nationalism sprouted the pervasive use of machines from the capital deepening of businesses to raise productivity: the McCormick mechanical reaper and John Deere ploughs became mainstays on farms; the McKay sewing machine was embraced in the bosom of textiles; foundries imported Britain’s Bessemer process to smelt iron into steel; Samuel Morse standardized telegraphy for instant communication with his eponymous code disseminating news in seconds; Gustavus Swift’s refrigerated railcars created a national market for perishables. These marvels indelibly altered the DNA of American capitalism.

Like any agrarian society America once languished at a subsistence level with a constellation of cottage industries. Local general stores carried limited inventory; artisans fabricated bespoke items in small quantities; blacksmiths forged metal for the utilitarian needs of a community; farmers were by and large landlocked. America was merely a patchwork of niche markets. In time the creative destruction wrought by railroads completely upended this inertia. Sears, Roebuck, and Co. would be established in Chicago’s epicentre of railroads for its mail-order business; smokestack industries found a renaissance in major cities; centralized commodity exchanges and grain elevators would become synonymous with railroad junctions. Places which were once trading outposts like Chicago, Atlanta and Houston found new life as cradles of business. Disparate regions discovered new identities as the breadbasket, steel belt, or coal country of the nation. Such diversification is the real legacy of railroads which reimagined supply chains by inaugurating just-in-time deliveries. Rivers were constrained by geography. Roads remained at the mercy of inclement weather. Railroads however transcended the banalities of transportation to consolidate a national market into a primus inter pares of production in relation to Europe.

0 notes

Text

Big-Push Pump Priming for Take-Off

I am never sure of time or place upon a Railroad. I can't read, I can't think, I can't sleep — I can only dream. Rattling along in this railway carriage to the music of the rails, I am in a state of delightful confusion. Charles Dickens, The Uncommercial Traveler, 1860

America’s antebellum economy midwifed a productivity blitzkrieg when quadruped and waterborne commerce could not approximate the speed of trains as surrogates to transportation. Essentially a full arsenal of industrial policy was deployed in revolutionizing supply-chains whereby Carnegie’s steel empire flourished behind tariff walls whilst railroad monopolies held favour with government. Protectionism then primed the pump for economic revolution. As opposed to being a monolithic exercise of industrial policy its multidimensional nature provided for the use of trade barriers, subsidies and other species of discrimination in unison. Quite suddenly something unforeseen manifested: a boom of capital formation with the geometric proliferation of factories, foundries and farmsteads. Almost unthinkably one proverbial seed created an entire forest within a generation. A chain-reaction of growth ensued from steel mills in Pittsburgh, stockyards in Chicago and skyscrapers in New York. The strategic fusion of public and private interests was the impetus behind this new age of American hegemony. Washington’s gamble on railroads was obviously fraught with risk but in hindsight this investment yielded dividends of astronomical value. Market forces alone could never replicate the cadence of this industrial expansion.

Vast distances were a scourge on the voluntary exchange of goods which hobbled America’s development. Such structural deficiency could only be remedied by what Economist Paul Rosentein-Rodan (1943) christened ‘big-push industrialization’ to crescendo into what W.W. Rostow (1956) dubbed a period of ‘take-off’. For the dilettante this scenario can be analogized as the velocity of a plane before it is airborne. But how to generate this precious momentum? Answer: A big-push of investment and protections to mobilize labour and capital at scale. A Keynesian stimulus of this sort invariably creates jobs and wealth downstream. By reasoning from first principles Washington began to court central planning to correct the market fragmentation that beleaguered the country since its inception. Solve the sprawl of geography and growth summarily follows; build railroads and complementary industries experience a halcyon era. By creating the demand for steel as Economist John Maynard Keynes might petition you inaugurate a multiplier effect that sees a boom in industry, wages and population. Or if reworded in the vernacular of Rodan a ‘big-push’ is invariably succeeded by ‘external economies’ — cause and effect. Thereafter the plethora of wealth creation was self-reinforcing as capital markets themselves became emboldened to invest with abandon.

There was no end to the increasing returns to scale ushered by railroad infrastructure. Each kilometre pared down freight costs. Each junction was shadowed by telegraph poles dispatching messages. Each extension begot a constellation of downstream benefits. A positive-sum game resulted where the expansion of one sector had a commensurate effect on another. If New York, Buffalo and Rochester were borne out of canals then Chicago, Kansas City and Omaha sprung up courtesy of railroads. This leviathan of infrastructure unleashed the energies of industry whose scale economies would see the widespread reduction of cost: in a postbellum economy rates per ton mile plummeted by 50 percent; farm incomes soared just as Chicago morphed into an entrepôt for western grain in its destination towards New York from 14 cents per bushel to 38 cents between 1858 and 1890 (Taylor and Neu 1956:2). Lesser intervals of time between farm-to-fork and mine-to-metal saw salutary effects almost universally. These heady times were a harbinger for the founding of Cornell University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology which sought to appease the demand for skilled labour in the 1860s. A real bellwether for this railroad mania was how capital-intensive industries were the trend du jour.

Soon enough the ubiquity of high-quality steel from the demand by railroads was directed towards the vertical ambitions of metropolises. Before high-rises punctuated skylines however a catalyst was needed to convince public opinion on its merits. The Great Fire of 1871 in Chicago became the impetus. Fourteen years later the archetype for a new generation of steel edifices proudly stood in the former ash heap whose design later found purchase on the landscape of other cities. Indeed not only was urbanization part and parcel of the ‘external economies’ from railroads but so too was the revolution in urban architecture. Bricks were relegated to the facade of buildings in favour of steel skeletons for the interior which commanded higher altitudes courtesy of their tensile strength. With real estate at a premium the city of New York fervently espoused this innovation to continue its tradition of building upwards in response to the inherent limitations of cast-iron. Ironically the same material used for the lateral transportation of goods saw new usage in its vertical conquest above city streets. The industrial policy of railroads then cascaded outward in a slipstream for other sectors to follow which in this case caused a wholesale reinvention of the downtowns in commercial centres.

Trains and towers were the insignia for the weltanschauung of capitalism that defined the spirit of America in its nascency. The spoils of one revolution in transportation spurred another in construction. This is the reason why industrial policy particularly when it pertains to infrastructure can be a lodestar for the development of a nation. A torrent of spillovers manifests without intervention because free markets latch onto this stimulus autonomously. Subsidies for railroads were au fond the brainchild of the desiderata by frontiersmen to expand westward. Nothing in the tea leaves would have ever suggested however that eventually a whole new steel industry would outproduce the entire European continent. The vast tentacles of this industrial policy not only aroused revolutions in transportation and construction but they equally informed the private speculation of the high finance world as well. Capital markets were rabid for the securities and bond issuances from railroads which were countenanced by the imprimatur of Washington’s treasury. This bulletproof mitigation of risk even boasted an additional parachute as land grants from government were ideal collateral. Railroad capitalization was such a lucrative enterprise inasmuch as banking giant J.P. Morgan would be founded in 1871 to rationalize and finance the industry.

0 notes

Text

A Faustian Bargain: Schumpeter's Magic of Monopolies

Railroad iron is a magician's rod, in its power to evoke the sleeping energies of land and water. Ralph Emerson, The Young America, 1844

Industrial policy universally remains the precursor to the take-off of industry whether it was in Britain, America or elsewhere. But a more clinical study reveals how one common denominator emerges in each vignette of such meteoric growth: monopoly rights. On every single occasion across recorded history where a laggard industrializes a prototypical paradigm is espoused. A curated few are anointed to be national champions: (i) the British East India Company and the Hudson’s Bay Company were darlings of economic growth for London; (ii) the Dutch East India Company was the Netherlands’ janissary to brave the high seas; (iii) America chartered the juggernauts of the Pacific and United States Mail Steamship Companies to reconcile the Western frontier with the Atlantic Seaboard; (iv) the triumvirate of Ford, General Motors and Chrysler achieved market dominance at the beck and call of Washington; (v) North American Aviation and Rocketdyne outflanked the Soviets in America’s space odyssey; (vi) Boeing and McDonnell Douglas bestrode the sector of commercial aircraft; (vii) Pan-Am, United and TWA were incubated in mail-route subsidies. In each new venture fraught with prohibitive fixed costs any scalability requires stable revenue. Oligopolies therefore are established to marginalize smaller competitors whose presence are anathema to innovation and swift industrialization.

Industrial policy takes a myriad of shapes and the hegemony via monopoly rights whether by public procurement or other privileges perennially remains the sine quo non of innovation. Quite simply when a company finds themselves awash with capital they are far likelier to adopt state-of-the-art technology in an abbreviated time frame. Yes, legislated favouritism at first blush does appear unjust but it eclipses any other accelerant. If abandoned to the mercies of free markets fast development would be next to impossible. When government dotes on a select few their capital accumulation as de facto monopolists enables them to grow apace. Indeed the long history of industrialization shows it has never been the child of laissez-faire capitalism. In every single instance has there been the presence of government intervention. In America’s industrial firmament the majority of companies have become household names as the direct progeny of tariffs, subsidies or charters. This Hamiltonian philosophy of protecting infant industries against entrenched incumbents from abroad has been a repudiation of Economist Adam Smith’s invisible hand at least in the embryonic stages of growth. So whilst it may be a Faustian bargain of pricing out smaller companies this sacrifice of market liberties heralded a Golden Age.

The magic of monopolies was a force disrupter in the 19th century. What free market purists habitually fail to acknowledge is how the ‘creative destruction’ of a few firms perpetually remains the lynchpin of frenetic growth. The foregoing neologism first coined by Economist Joseph Schumpeter throws into relief how businesses with stable profits when unencumbered by competitors demonstrate a boldness in their expansion. Why? Companies which have amassed a war chest of capital plough their money more liberally into technology, capital assets and vertical integration to preserve their market dominance. For instance the incipient stages of America’s industrial revolution largely hinged on the railroad monopolies sponsored by government as they sought sturdier and cheaper steel at scale. The spillover from this hunger precipitated the adoption of Britain’s Bessemer process whose innovation later transcended rails as the advent of skyscrapers began to inform the skyline silhouettes of cities everywhere. Akin to economic jazz a synergy spontaneously manifested between railroads and steel mills as the rest of American businesses rode the coattails from the attendant rise in productivity. Mass production therefrom implied more tracks, heavier tonnage on those said tracks and the substitution of masonry with steel for buildings.

The externalities from railroad monopolies were many. It is not hyperbole to state America’s formative years were built on the back of railway demand after first being the beneficiary of maritime commerce and state-sponsored infrastructure like inter alia canals, ports and lighthouses. In the absence of these monopolies the fast cadence of industrialization would have been stillborn devoid of the springboard purveyed by government. Lawmakers took great pains to foster this infrastructure by being guarantors of stable profits whose knock-on effect conduced to stable markets for steelmakers. The Gilded Age then is the legacy of this synergy wrought by the paternalism of industrial policy amidst the heyday of wealth and urbanization. Contrary to conventional wisdom the robber barons of this era did not manifest ex nihilo by bootstrapping their own riches. Andrew Carnegie’s steel empire, John D. Rockefeller’s oil kingdom, Cornelius Vanderbilt or Jay Gould’s railroad fortunes all derived from real estate allotments on public land, eminent domain authority, route monopolies, mail contracts, direct subsidies and more. Unbeknownst to the layman these industry captains were not entirely self-made. In a social bargain of a utilitarian nature a few rent-seeking companies would become handmaidens to America’s exceptionalism.

Henceforth no longer would the nation be an agrarian confederation but rather an industrial heavyweight. Commerce could be swiftly conducted over savage terrains and forbidden plains in a matter of days not weeks. The achievement of industrial policy for railroads was to truncate time whereby America industrialized in less than half a century. The real muscle behind the Union’s Manifest Destiny was this lattice of iron crisscrossing the nation. Railroads thus revolutionized production insofar as this infrastructure was a fillip to the transportation of freight and people where things organized themselves organically between the merchant class in bustling cities and the farmers and miners in far-off counties. All that was required to jumpstart this growth was the seed of industrial policy bestowing privileges upon a few business interests. By 1900 America’s production exceeded that of Great Britain which hitherto was lauded as the world’s workshop (Wright 1990:652). Where maritime commerce might have been nation-building the humble railroad was itself empire-building. Such continental integration through rail links across a landmass larger than Western Europe spawned new epicentres of business overnight. This economic miracle was unfathomably quick.

0 notes

Text

Iron Horses

Tradition is not the worship of ashes, but the preservation of fire. Gustav Mahler (1860-1911)

Since 1812 when John Stevens awakened the public to the utility of locomotives over the liabilities of boats the government’s patronage for railroads has galvanized America’s growth. Upon the miniaturization of steam engines for trains first pioneered in Britain came a new entente between the Atlantic seaboard and Western frontier. Such infrastructure swiftly evolved into a fillip to nation-building and a function of westward expansion for homesteaders as business interests shrunk time and space across the continental economy. Finally the hinterland’s bounty of raw materials would be wedded to smokestack cities wherein factories and meatpacking enterprises tended to the consumption habits of a nation. In short order did railroads see to the obsolescence of America’s agrarianism. Therefrom a cascade of economic activity manifested based upon the scale economies of a unified market: farmers adopted mechanization in a departure from mere subsistence towards cash crops; timber mills ramped up their crossties for rail tracks in a symbiosis of industry; meatpackers availed themselves of refrigerated railcars to enter new markets; steel foundries never slept; Western Union’s telegraphy fledged into America’s nervous system by dispatching news across wires above railway real estate. At long last was the tyranny of distance no more.

What once required a fortnight took forty hours as these iron horses whisked goods and people to faraway places quicker than their maritime counterparts. Not bound by the immutable character of topography nor its seasonality in the case of icing atop the Mississippi or Hudson rivers the invention of the train ventured well into the interior. Economic opportunities then abounded in virtue of this supply chain revolution since swathes of America were emancipated from previous isolation: energy-intensive industries devoured coal sourced from Appalachia; wheat bushels harvested from the Midwest breadbasket fed population booms in metropolises; rich iron ore deposits mined in Minnesota and Michigan were the grist for Pittsburgh’s steel empire; hardwood from the Pacific Northwest and Great Lakes birthed a renaissance in construction; crude oil’s discovery evolved from a mere curiosity into the lifeblood of a nation upon Edwin Drake’s maiden extraction in 1859. Railroads thus came to inaugurate a magical symbiosis between upstream and downstream industries wherein the influx of commodities spurred the wealth of finished goods — each now able to maximize his core competency. This infrastructure thereby disrupted American industry and brought forth production at scale.

Once more the stimulus for experimenting with railroads issued from the mercantilism written in Alexander Hamilton’s 1791 ‘Report on Manufactures’ which sought to mix statecraft with industry. This seminal treatise kindled a boom in such infrastructure where private capital alone would have been unable. Hamilton’s literal ‘facilitating of the transportation of commodities’ inspired by London’s own canals and roads became the fodder for a nascent industry to assist in the trade of manufactures. As soon as the American public was captured by the idea of railroads from their former masters in metropolitan Britain a new age would commence. A virtuous cycle emerged: the protectionism of high tariffs against foreign steel allowed ironworks to plough profits into meeting the demand for new railways which themselves were buoyed up by the fiscal policy of subsidies and land grants. Soon enough the scaffolding of Hamilton’s doctrine funded and scaled this infrastructure to integrate disparate regions into a single market. The multiplier effect here from the foregoing trade creation would in turn inform the alacrity by which the industrialization of America’s Manifest Destiny proceeded. Long gone was the era of stagecoaches and steamboats as deflation ensued with the albatross of distance no more when prices for goods commensurately fell by 50 percent (Atack 2013: 316).

Year-round transportation wrought by railroads irrevocably altered the young republic since stakeholders could specialize in their trade. The regular dispatch of commodities and finished goods between producers and consumers and its promise of little to no disruption enabled the adventurism of businesses to innovate. Indeed the sinews of any economy in its modernization are indelibly infrastructural by nature. The umbilical cord that connects the hinterland to the heartland is what mobilizes capital and goods for the telos of wealth creation. Like a proverbial house nothing can be built bereft of its foundations. Ergo America’s ascent was primed by each successive revolution in transportation from turnpikes, to canals, to railways and onwards. With the yoke of distance gone it was incumbent on producers to become more sophisticated in their output. Wiser and better methods would be found to raise livestock, cultivate grain or manufacture steel whereby a species of cross-pollination manifested to catapult growth everywhere. It is not happenstance at all that America’s vaunted Gilded Age beginning in 1870 made bedfellows of the railway boom as trade barriers precipitously fell. Such private fortunes were amassed by the proliferation of commerce and the growth of cities in equal measure.

This era of prosperity was born on the back of railroads and the Hamiltonian ethos that fostered it. In less than a single generation did the mileage of track surge in an exponential increase by a factor of 798.87 from 23 miles to 18,374 between 1830 and 1850. Where rail lines converged so too did industry. The consolidation of a continent mades niches and nodes out of cities as job creation and agglomeration economies were had by sleepy outposts as each exploited their latent factor endowments: Pittsburgh burgeoned into a cradle for metalworking from its proximity to coal and iron ore; Chicago transformed into a meatpacking hub from its proximity to livestock in the Midwest; Milwaukee’s status as a brewery capital with its German population of the Schlitz, Miller and Pabst families stemmed from its proximity to barley fields in the interior; Toledo’s glassware production was the upshot of Lake Erie’s sand deposits and their unusual purity; Seattle grew into a gateway for lumber. Each city’s know-how in these industries followed from the prime mover of railroads traversing prairies and mountain passes to spur urban growth and industrial development. Prior to the advent of railways localities were fettered by the need to produce a broad range of goods but once introduced these cities began to specialize in one or two staple industries.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Moby Dick

There is a witchery in the sea, its songs and stories, and in the mere sight of a ship, and the sailor's dress, especially to a young mind, which has done more to man navies, and fill merchantmen, than all the press gangs of Europe. Richard Henry Dana Jr., Two Years before the Mast, 1840

0 notes

Text

Economic Statecraft

Man cannot discover new oceans unless he has the courage to lose sight of the shore. André Gide, 1947

Between the postcolonial Tonnage Act, lighthouse proliferation, the Erie Canal’s inauguration, mail subsidies, the Panama Canal moonshot and the Great Depression’s ex post legislation statecraft has perennially been a prime mover. These vignettes essentially belie free market purists whose reductive views do not align with history. At critical moments across America’s storied past has industrial policy purveyed the seedbed for economic development. Of course the magic of free enterprise creates wealth in the spirit of Adam Smith’s invisible hand but government perpetually remains a handmaiden to it bereft of which nothing would take root in barren soil. A myopic exegesis conflates effect with cause. Such a ‘chicken before the egg’ fallacy remains blinkered to how the apposite conditions must exist as a precursor to the works of laissez-faire capitalism. Ergo there is a special place for government when a country finds itself in the midst of industrializing. Rather than anathema to growth this intervention begets a matrix wherein firms are vested with the latitude to innovate whilst immune to liabilities hence their carte blanche enables them to gestate. Or if not for the right infrastructure these same outfits would be deprived of markets particularly where it relates to their supply chains.

During the nascent years of the Republic in the wake of the Revolutionary War economic nationalism bore the imprimatur of Alexander Hamilton whose advocacy captured a vast audience. With the inordinate clout of British imperialism still looming large over America it behooved President George Washington to channel this doctrine in his government so London’s predations could be checked. It followed that the Tonnage Act of 1789 imposed onerous levies on foreign ships not only as a method to generate revenue but equally to hem in infant industries against the maritime monopoly of Britain. Import-competing shipbuilders could finally carve out a space for themselves where they were once unable. Henceforth America would not be beholden to its counterparts for the carriage of its wares and fare nor would it be idle in the defence of its proper interests overseas. By discriminating against competitors domestic industries catapulted the country into the pantheon of a seaborne power. By stimulating demand for American-made ships producers reaped a windfall of capital whereby they could plough it into their expansion. By running afoul of free trade orthodoxy foreign industries no longer prostrated shipbuilding at home. The Tonnage Act made America a great power to be reckoned with.

Whilst sharing the same vintage as this legislation the federalization of maritime infrastructure also came to substitute for the piecemeal efforts led by states in governing lighthouses. Where trade routes might have once been neglected these upright sentinels lighting the path for ships began to take precedence. Since private investment did not square with the reality of such a public good insofar as the free-rider dilemma disincentivized individuals from contributing to its provision this beckoned government to intercede. Thereafter lighthouses became the ward of the federal treasury. Rather than fall into disuse the proper funds saw to the upkeep of this infrastructure. Lighthouses were unambiguously the sine quo non to the safe passage of ships and this industrial policy made sure that underinvestment no longer beleaguered their operation. Through the mitigation of maritime hazards government attended to the constellation of interests between shipwrights and mariners who could now be assuaged of their anxiety about voyages at sea. Were it not for the Lighthouse Act these same trips would be fraught with the perils of having vessels run aground or worse. Insurers thus breathed a sigh of relief. Although perhaps a roundabout way this investment certainly gave patronage to the maritime industry.

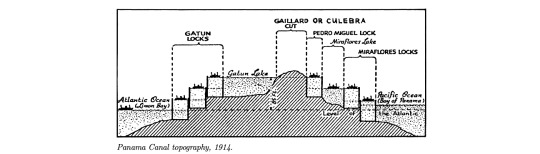

In the same vein as infrastructure the heavy-handed industrial policies giving vent to the Erie and Panama Canals were equally landmarks in America’s development. By cleaving a path through the wilds of the Adirondack region for a gateway to the Atlantic or parting the Isthmus of Panama in two it followed that dividends were had by all. America’s breadbasket in the interior would unite with the cosmopolitan metropolis of New York and the quasi-teleportation portal in the South abridged the journey of commerce between the Western and Eastern seaboards. These corollaries to industrial policy birthed westward expansion in keeping with the providence of Manifest Destiny before the ubiquity of railroads. Both of these monuments to government dirigisme truncated time and transportation costs such that these shortcuts enhanced the competitiveness of America’s exports and imports. Where in a bygone time the prohibitive sum of outlays deterred industrialization now the economic calculus indelibly changed. What these monolithic pieces of infrastructure wrought then was a reconfiguration of trade from a dribble to a torrent of volume. Quite precipitously were capitalism’s animal spirits awakened once nature had been conquered between the Hudson River and Lake Erie or via Panama’s thoroughfare.

The last method by which America trafficked in industrial policy for the maritime sector since jettisoning the British yoke of imperialism entailed both mail and direct subsidies. The former in the guise of the 1845 and 1847 Acts of Congress underwrote packet ships and steamships alike as a stimulus to harness the winds of commerce. By subsidizing mail service Washington feathered an impetus to businesses so they may bootstrap their own growth. A steady stream of revenue promised these firms a lifeline to weather the vagaries of markets with a long term outlook to plough capital into further expansion whether it be in the size of fleets or in the number of trade routes. Upon lowering risk it made private investment more attractive. In turn a stronger Merchant Marine would be a counterpoise to the British Empire that long claimed dominion over the seas. As for direct subsidies like the 1916 Shipping Act or the 1936 Merchant Marine Act they centralized authority between the Shipping Board and the Maritime Commission respectively in order to spur the drumbeat of industry. America’s supply chains diversified in earnest under their purview with the buildup of inventory in ships. Rather than being some derivative footnote all the aforementioned industrial policies nurtured America until it bestrode the world like a giant.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Modernizing America's Fleet

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold; Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world, The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere The ceremony of innocence is drowned; The best lack all conviction, while the worst Are full of passionate intensity. William Butler Yeats, The Second Coming, 1919

Although President Woodrow Wilson was partial to isolationism his dovish predilection could not be reconciled with WWI which contravened all etiquette pertaining to freedom of the seas. German U-boats prowling the North Atlantic ran roughshod over ethics governing the longstanding neutrality of merchant shipping in an escalation of submarine warfare. With material losses mounting akin to a game of cat and mouse across unfriendly waters an existential threat emerged against Allied powers. Europe’s fratricide of the Great War made obsolete the traditions of yore where belligerence was once reserved for combatants alone away from civilians. With America’s ships imperilled the federal government took it upon itself to create the world’s largest fleet by 1922 (Roland 2007). Six years out from the Act’s inception the gross tonnage of vessels soared by 117 percent in a renaissance at sea for the fledgling economy. How the heyday of shipbuilding came to be was through the Act’s Shipping Board which fostered the industry’s growth in a centralized manner. No longer would the Merchant Marine languish as statesmen recognized it to be part and parcel of America’s well-being with the floodgates of federal funding now open. A building boom was afoot.