Text

Geometric Simulation for 3D-Printed Soft Robots- Juniper Publishers

Introduction

Robots fabricated by soft materials can provide higher flexibility and thus better safety while interacting with natural objects with low stiffness such as food and human beings. With the growth of three-dimensional (3D) printing, it is even possible to directly fabricate soft robots [1,2] with complex structures and multiple materials realizing highly dexterous tasks like human-interactive grasping and confined area detection [3]. However, with such increased degrees of freedom (DoF), the design of soft robots becomes a very difficult task. It can be made possible by integrating simulation into the design phase. However, the shape deformation comes from many different and complex factors including manufacturing process, material properties, actuation, etc. Especially with the limited understanding of layer-based additive process in AM, it is challenging to formulate a complete mathematical model for the simulation.

SOFA [4] is one of the most widely used frameworks for physical simulation. It is also applied in the simulation of soft robots that supports interactive deformation [5]. However, it may suffer from the problem of numerical accuracy, particularly if there is large deformation. Unfortunately, one benefit of soft robot is its capability of adapting to highly curved contact by large deformation, which needs to be precisely simulated for many applications. There is another type of simulation methodology to simplify the simulation model of deformation to a geometry optimization problem [6]. It was originally developed in the computer graphics area for visualization, but it has been proved to work superbly in physical simulation like self-transformation structures [7] and the computational efficiency is remarkable [8]. This geometric simulation is particularly suitable for soft robots [9] (Figure 1), because the actuation of soft robots is commonly defined by geometry variations (e.g., cable shortening and pneumatic expansion), and it is actually indirect to first obtain apply them in the conventional deformation simulation. It is shown that the geometric simulation gives better convergence and accuracy than the conventional methods. Therefore, the aim of this review is to share this technique with a broader audience in the robotic community, and discuss the potentials capabilities, and future works of this technology.

Geometric Simulation

The common way of Finite Element Analysis (FEA) is to apply Hooke’s law to each element and then assemble the equations to compute the deformation with the applied force:

where 𝐹 is the global nodal force vector, 𝐾 is the global stiffness matrix, and 𝛷 is the global nodal displacement vector. In the geometric simulation, the formulation is developed by shape projection on the elements in terms of point positions:

where 𝐕 ∈ ℛ𝑛×3 stacks all the point positions of 𝑛 vertices, Ci ∈ ℛ𝑒×𝑛 is the centering matrix for the 𝑖-th element among 𝑒 elements, Pi ∈ ℛ 𝑒×3 is the variables defining the shape projections for the element, and 𝑤𝑖 is the weight for the element, which is commonly set as the volume. This minimization can be solved by taking derivative and thus a sparse symmetric positive definite system:

This geometric optimization is formulated to minimize the elastic energy with reference to shape variations similar to the physical phenomenon during deformation. To compare Eq. (3) with Eq. (1), they have the same form with:

Therefore, the geometric simulation actually has the benefits as the FEA, but it should be noted the force vector 𝐹 here is defined purely by the shape projections. As a result, this is a direct approach to take the geometric actuation as input and compute the deformed shape of soft robots by numerical optimization using a geometry-based algorithm. To complete the formulation, the shape projections should be carefully defined to model different actuations in the simulation and to model the material properties geometrically. In the state-of-the-art work [9], the geometric constraints of actuations are modeled as a type of element, e.g., aligning the cable with the edge of elements and shorten the edges, or scaling the size of elements for volume expansion in pneumatic actuations. In such way, the actuation can be directly integrated in the optimization without additional computation burdens. In terms of modeling the material properties geometrically in the framework, a calibration step is done to learn the relationship between material properties and shape parameters between hard and soft assignments. Should the element be rigid or preserve its volume is determined by the shape parameters and modeled by the shape projection. It is shown that the calibration method can be used to simulate the deformation of objects with two materials. Different from using constrained nonlinear optimization, the geometry optimization can converge in a few iterations, thanks to the shape projection operator.

0 notes

Text

Light-Weight Secure IoT Key Generator and Management- juniper Publishers

Abstract

Security is a critical element for IoT deployment that affects the adoption rate of IoT applications. This paper presents a Light-Weight Secure IoT Key Generator and Management Solution(LKGM) for industry automation and applications. Our solution uses minimum computing and memory resources that can be installed on half-credit-card-size embedded systems that enhances the securityof end-to-end communications for IoT nodes. A frequently changed randomly generated passphrase isused to authenticate each IoT node that is embedded with an encrypted unique authentication key. Fieldtest results were presented for an advanced manufacturing application that will only be activated whentwo authenticated IoT nodes are within the vicinity.

Keywords: Authentication; Authority; Secure key; IoT; Security; Industry automation

Introduction

Internet of Things (IoT) is a network of physical objects that have unique identifiers capable ofproducing and transmitting data across a network seamlessly. IoT system refers to a loosely coupled,decentralized system of devices augmented with sensing, processing, and network capabilities [1,2].IoT is projected to be one of the fastest growing technology segments in the next 3 to 5 years [3]. IoTapplications are being developed and deployed in an exponentially increase manner in many smart city’s initiatives around the world. Gartner Group has estimated that there will be 25 billion connectedIoT devices by 2020, and that IoT services will constitute a total spending of $263 billion.Unfortunately, this growth in connected devices brings increased security risks [4]. As indicated byFrost & Sullivan[5]; Miorandi et al., and Weber[6,7], security is the major hindrance for the wide scale adoption of IoT. Inaddition, the increasing use of multi-vendors IoT nodes which are often only have minimum securityprotection that resulted in more complex security scenarios and threats beyond the current Internet iswill arise.Constant sharing of information between “things” and users can occur without proper authentication and authorization. Currently, there are no trustworthy platforms that provide access control andpersonalized security policy based on users’ needs and contexts across different types of “things”.The “things” in any IoT network are often unattended; therefore, they are vulnerable to attacks.Moreover, most IoT communications are wireless that make eavesdropping easy [6,8]. The futurewidespread adoption of IoT will extend the information security risks far more widely than the Internethas to date [9].

In an ad-hoc IoT network where IoT nodes are localized and self-organized, network infrastructureis not required. Security of the IoT nodes that operate in such ad-hoc peer-to-peer networks areincreasingly becoming an important and critical challenge to solve as many applications in such IoTnetwork becomes commercially viable. As ad-hoc IoT network has a frequently changing networktopology, and the IoT nodes have limited processor power, memory size and battery power, acentralized security authentication server/node becomes impractical to be implemented.

Methods

In our applied research work, “KeyThings” was developed as part of the project title “Collaborative Cross-Layer Secure IoT Gateways” funded by the Singapore NRF-TRD. Our solution consisted of two main systems, namely the Security Key Generation System (SKG) and Security Key Management System (SKM). The objective of our project is to allow an IoT application (e.g. a web service, etc.) to be activated only when a pre-determined number of authenticated IoT nodes are within the vicinity. This enhances the security of the IoT application by authenticating the hardware (i.e. IoT nodes) instead of just authenticating based on the usual usernames and passwords. The authentication process is done in the system’s background without the need for human intervention which is critical in some operation environment (e.g. manufacturing, production, remote sites, etc.) where not all staff are given access to the sensors’ readings due to security issues. The staff are categorized into “non-authorized”, “operator” and “supervisor”.

Below are the features of our Solution

a. “Non-authorized” personnel who are not issued with the authenticated IoT node will not have 60 access to the sensors’ readings.

b. Only authorized “operator” who has an authenticated IoT node is able to view the sensors’ 62 readings only when the “operator” is in the vicinity.

c. The authorized “supervisor” with an authenticated IoT node that is with higher access rights, 64 can view the sensors’ readings and the summary report. If the “supervisor” leaves the vicinity, 65 the summary report will no longer be available.

d. All authentications are done in the solution’s background without the need for human 67 intervention.

Solution Setup

Equipment (Figure 1)

A. The setup consists of the following equipment

a. Authentication Server

b. Client device 1

c. Client device 2

d. Application Server

e. Tablet

Authentication server (KeyThings-Server): The authentication server is the “brain” of the security key management. It has the following 92 responsibilities:

A. Access point: Serves as the access point to the entire system.

B. Generate random passphrase periodically

i. If there is no authenticated device, the passphrase will remain the same.

ii. If there is one or more authenticated device, a new random passphrase will be generated at 98the end of each time interval (after every 5 MQTT broadcasts).

C. MQTT Server: It will broadcast the generated passphrase via MQTT to all subscribedKeyThings-Clients.

i. Once every 2 seconds.

ii. MQTT topic: authentication/challenge

D. Web Server via REST API.

E. For KeyThings

i. -clients to submit their encrypted passphrase.

ii. For application server to query the number of authenticated devices.

F. Authentication: The server stores the encrypted credentials and MD5 of the KeyThings-Clients that were generated from the Security Key Generation System.

Client devices (KeyThings-Client): Each client device contains the unique security key that is used for authentication to gain access to 113 different web services. The key must be generated from the Security Key Generation System. Thedevice has the following responsibilities:

A) MQTT client. Registers and listens to the broadcasted passphrase.

B) Encryption. Encrypts the passphrase that was received via MQTT.

a. If the received passphrase is the same as previous passphrase, the device will just ignorethepassphrase and does nothing.

b. If the received passphrase is different from the previous passphrase, then the passphrase will be encrypted.

c. HTTP Request / Response. Send the encrypted passphrase to the authentication server(KeyThings- Server) once the encryption has been completed.

Application server: The application server hosts the production webpage (i.e. the machine readings and summary report). It is currently running on Raspberry Pi, but it can be hosted on any environment (i.e., Windows or Linux) that has network connectivity to the Access Point. The application server has the following responsibilities:

a) HTTP Request / Response: Host the webpage that can be access via the tablet.

Tablet: The tablet is used to view the web page that contains the manufacturing data (machine readings andsummary report) from the application server.

Result

Below is what you will see when different numbers of devices have been authenticated Figure 2.

Discussion

The test was conducted successfully with results indicated that a light-weight security key generation and authentication method can be easily implemented in a distributed manner for a self-organizingnetwork to enhance IoT nodes and service level security in an industry automation environment. The method and the solution can be applied to provide features such as multi-level security for different stake holders in an advanced manufacturing environment, multi-factor security keys, user definable security- based services and policy, etc. The solutions can easily be scaled and adapted to suite various industry needs and expectation in enhancing the security of IoT nodes, sensors, PLC controllers, robots, etc. to meet their business needs.

Conclusion

In this paper, a Light-Weight Secure IoT Key Generator and Management Solution (LKGM) for industry automation and applications for enhancing the security of peer-to-peer communications among IoT nodes is presented. The LKGM is integrated to half-credit-card-size embedded systems. Our experimental results showed that the solution enhances secured peer-to-peer IoT communications amongst the IoT node. Field tests were conducted successfully for a manufacturing application that uses web services.

For More Open Access Journals Please Click on: Juniper Publishers

Fore More Articles Please Visit: Robotics & Automation Engineering Journal

0 notes

Text

Comparative Analysis of the Use of the Pore Pressure and Humidity When Assessing the Influence of Soils in Transport Construction | Juniper Publishers

History of Civil Engineering

Juniper Publishers-Open Access Journal of Civil Engineering Research

Authored by Kochetkov AV

Short Communication

Now there is a question of reasonable applicability of indicators of pore pressure and humidity at an assessment of influence of indicators of soil in various environments and conditions of transport construction. Such an analysis can be carried out within the framework of the molecular kinetic theory of gases taking into account the photon interaction.

The real gas is not described by the clayperon-Mendeleev equation for ideal gases. Therefore, due to the needs of practice, many attempts have been made to create an equation of the state of real gases.

The most well-known equations for real gases are given in Table 1.

Some equations are a refinement of the equation of van der Waals (Dieterici and Berta), and equation Beattie-Bridgeman and Redlich-Kwong are empirical, without physical justification. In this case, Redlich writes in his article that the equation does not have a theoretical justification, but is, in fact, a successful empirical modification of the previously known equations [1]. A large number of equations due to the fact that no equation describes the behavior of real gases under all possible conditions (temperatures and pressures). Each equation has areas in which it best describes the state of the gas. But in other conditions, the same equation has large deviations from the experimental data. In practice, only the van der Waals equation is used in the form of direct calculations due to its simplicity. For other equations, either charts or tables of calculated values are typically used.

The meaning of the van der Waals equation is not only that it is the simplest, but it also has a clear and simple physical meaning. “Despite the fact that the equation of van der Waals equation is an approximate, it is sufficiently well suited to the properties of real substances, so basic provisions of the theory of van der Waals forces remain in force to the present time, exposed to the modern theories that only certain clarifications and additions” [2, p. 59]. “It was indicated that the modern theory of the equation of state of real gases is based on the fundamental provisions of the theory of van der Waals and develop these provisions further, and, having powerful mathematical apparatus of statistical mechanics, it gets the ability to produce all calculations are approximate, but quite accurate” [2, p. 60].

The citation clearly indicates that statistical mechanics is used for accurate calculations based on physical models.

The fact is that thermodynamics is a phenomenological science. It is possible to obtain experimental data on the state of gases at different thermodynamic parameters and to approximate the most suitable thermodynamic equation even without having any idea of the internal mechanisms of the processes occurring in the gases. This is exactly what the authors of the gas laws did: Lavoisier, Boyle, MARRIOTT, etc.

But if you try to delve into the essence of the processes occurring in gases, then a mathematical apparatus is inevitably necessary, taking into account the interaction of the molecules and atoms that make up the gases. This is the apparatus of statistical physics. But, to statistical physics problems of their own. “The exact theoretical calculation of the statistical sum of gases or liquids with arbitrary Hamiltonian (2.6) is a problem that lies far beyond the capabilities of modern statistical physics” [2]. Although,” it is possible to make a number of reasonable and sufficiently good approximations that allow us to estimate the statistical sum (2.1) and the configuration integral (2.8) for real gases consisting of valence saturated molecules “ [2]. The task is still far from over. A reasonable choice of initial parameters plays an important role in the difficulties faced by researchers of real gases. We will carry out a methodical analysis of the initial parameters used in the theory of gases. Currently, the following thermodynamic parameters are used in the scientific and educational literature: P (pressure), V (volume) and T (temperature). If the temperature and volume are not in doubt, the pressure, as a thermodynamic parameter, raises certain questions. Consider the compressibility factor (a measure of pressure of gases). It is believed that “the most convenient measure of nonideality is the compressibility factor Z = pVm / RT, since for an ideal gas Z = l under any conditions” [2]. For example, it is proposed: “the thermal equation of state of a real gas can be represented in the form pv = zRT,

where z is the compressibility factor, which is a complex function of temperature and density (or pressure)” [3].

But as a parameter for determining the thermodynamic state of the gas system, compressibility is not very suitable, because firstly, it has a complex dependence on pressure and temperature. Any explanation of why and what determines the compressibility of gases is determined by the adopted model of the structure of gases. The form of the compressibility function for all real gases is given in [3] (Figure 1), and “for generality, the reduced pressure π=p/PK and the reduced temperature τ=T/TC are used as parameters here, where PK and TK are the parameters of the substance at the critical point. Since for an ideal gas at any parameters z=1, this graph clearly represents the difference between the specific volume (density) of the real and ideal gases at the same parameters”[3] Figure 2.

Secondly, the compressibility of gases cannot be directly measured during the working cycle of a thermodynamic system, but only during specially conducted experiments. Third, the compressibility of gases, in fact, is not a single curve, but a family of curves, at different temperatures and the same pressure, or at the same temperature, but different pressures, the compressibility of the gas is different. In practical work, the compressibility of gases is not measured, but calculated according to the appropriate calculation formulas, according to officially recognized methods. Therefore, the compressibility of gases may well characterize the nonideality of gases but cannot be accepted as an initial parameter in the theory of real gases. Let’s see what else can serve as a replacement for the pressure as the initial parameter. For this it is necessary to pay attention to the parameters that are used in the statistical theory of gases. The literature analysis shows that all statistical models of real gases are constructed using such parameter as concentration. Concentration is the number of atoms (molecules) per unit volume.

This is not surprising, since it is the concentration that determines the average distances between the gas molecules, and hence the potential long-range forces of the molecules. For example, according to the theory of van der Waals or any other. Then, after establishing the laws of behavior of the statistical system depending on the concentration, go to the usual thermodynamic characteristics: P, V, Etc. The application of pressure as a thermodynamic parameter is perfectly justified in the theory of ideal gases, in which atoms interact only at absolutely elastic collisions during chaotic thermal motion. According to the theory of ideal gases, the relationship between pressure and gas density is very simple [4]:

P = NkT ……………… (1)

here P-pressure, MPa; N-concentration (1/m3); T – temperature.

At a constant temperature, the dependence between concentration and pressure is linear:

P = const*N …………….. (2)

The concentration of N is equal to the number of molecules per unit volume. Concentration is related to density by a simple ratio:

ρ = N*m …………………. (3)

where ρ is the density, N is the concentration, m is the mass of the molecule.

In other words, in the theory of ideal gases, the gas pressure is linearly proportional to the gas density. For real gases this is never the case. The theory of real gases takes into account the forces of interaction of a potential nature. “Real gases differ from their model - ideal gases - in that their molecules are finite in size and between them the forces of attraction (at considerable distances between molecules) and repulsion (when molecules approach each other)” [5]. This leads to the fact that the density of real gases will be nonlinear, and a simple replacement of the concentration of the pressure in the volume, as is quietly done in the theory of ideal gases cannot do.

Tradition of determining the parameters of gas pressure is since when in science was not known that gases consist of atoms [5, p. 36-65], and therefore, scientists could not operate with concepts of the concentration of atoms in gases. We do not consider it advisable to continue this vicious practice. Moreover, as mentioned above in the theory of real gases directly refers to the value of concentration, but in the final equations go to the pressure, “the old-fashioned way.”

For Figure 3 graphs of helium density change depending on pressure are given. The fat line is a theoretical line based on the ideal gas model [6].

From Figure 3 it is clearly seen that for the graph of the function for helium, not only does not coincide with the theoretical, but the dependence of the density on the pressure is not linear. We chose helium, not only because the characteristics of this gas are well studied, but primarily because helium is the most chemically inert gas. Due to its inertness, it is not located to form compounds in molecules and other aggregations. That is, in its chemical properties, it is closest to the ideal gas. We chose helium, not only because the characteristics of this gas are well studied, but primarily because helium is the most chemically inert gas. Due to its inertness, it is not located to form compounds in molecules and other aggregations. That is, in its chemical properties, it is closest to the ideal gas. When discussing compressibility as an initial parameter, we said that the main disadvantage of compressibility as a parameter is not direct measurements, but calculated values. Unlike compressibility, the density of gases can be measured directly, both in stationary gases (in tanks) and in pipelines. There are several types of density meters for both liquids and gases. Although densitometers are more expensive than manometers, but the gain in practical applications can be tangible.

Thus, based on modern theories of real gases, it seems more logical to determine the properties of gases, depending not on pressure, but on density.

1. First, because all models of statistical physics are based on the concept of concentration, not on the concept of pressure.

2. Secondly, because it is the density that is closest to the concept of concentration. And easily translated into one another.

3. Third, even if any characteristic of the gas (heat capacity, thermal conductivity, etc.) linearly depends on the density, in accordance with the models of the statistical theory of gases, the translation of the values of these properties depending on the pressure will make an additional nonlinearity, depending on the density of the pressure. Especially if the dependence of the function is nonlinear

As an example, consider the graphs of the dynamic viscosity of helium. For Figure 4 graphs of helium heat capacity versus pressure in the temperature range from 100K to 1000K are presented. For comparison, graphs of dynamic viscosity versus gas density are presented [7] (Figure 5).

The difference in the representations of the same gas property depending on different parameters is clearly seen from the graphs. The first thing we can say is that schedules of dependence of dynamic viscosity to the density look easier than the dependence of dynamic viscosity on the pressure is because of the nonlinearity of the dependence of concentration on pressure. In particular, viscosity graphs from pressure change their direction of change. And at low temperatures so quickly that the lines even intersect. Moreover, if at low temperatures (lower lines in Figure 3), under high pressure upwards, at moderate temperatures, horizontal, and at high temperatures (top line) a bit, about 2% down.

The graphs also depend on the density - all the lines are almost parallel throughout. And they do not change their behavior at all. But the fact that the graphs depending on the density (concentration) look easier is not the most important thing. The main thing is the epistemological value of such a transition to another parameter [5].

Summary

1. Another proof of the influence of thermal photons on the behavior of gases under different conditions is the experimental data on the compressibility of gases under different conditions.

2. Modern theories of real gases are unable to explain the behavior of the compressibility function. Nothing to do with the change in the density, and especially at different temperatures. Because according to modern theories repulsion of molecules should be observed only when molecules are smaller than the size of molecules. And the compressibility of gases should not depend on temperature at all.

3. The hypothesis of a significant influence of thermal photons on the mechanical properties of gases can explain the behavior of the compressibility factor of gases.

4. With an increase in the density of the gas, the compressibility factor increases because, together with an increase in the density of gases, the number of photons having a mechanical effect on the gas molecules also increases.

5. As the temperature increases, the energy of thermal photons increases, so does the compressibility factor (resistance of the gas to compression). Because more energetic photons have a stronger mechanical effect (stronger push) on the gas molecules. That is why the compressibility factor increases in the temperature range from 10 to 150 K.

6. At temperatures of more than 150 K, the number of thermal photons that have a mechanical effect on the gas molecules decreases, since the radiation of the gas outside increases. Increasing the number of photons leaving the volume of gas.

7. Reducing the number of photons in the gas volume reduces the internal pressure of the gas and, accordingly, the compressibility factor decreases.

8. The moisture index (corresponding to the concentration or density) used in the measurement of soil properties more accurately and reliably (has a large proportion of the explained dispersion) shows a more significant change in its properties in comparison with the pore pressure.

9. Accordingly, there is no reason to move to foreign standards based on pressure indicators in soils and other environments of transport construction.

For more Open Access Journals in Juniper Publishers please click on: https://juniperpublishers.business.site/

For more articles in Open Access Journal of Civil Engineering Research please click on: https://juniperpublishers.com/cerj/

To know more about Open Access Journals Publishers

To read more…Fulltext please click on: https://juniperpublishers.com/cerj/CERJ.MS.ID.555704.php

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Review of Reliability Factors Related to Industrial Robo- Juniper Publishers

Abstract

Although, the problem of industrial robot reliability is closely related to machine reliability and is well known and described in the literature, it is also more complex and connected with safety requirements and specific robot related problems (near failure situations, human errors, software failures, calibration, singularity, etc.).Compared to the first robot generation, the modern robots are more advanced, functional and reliable. Some robot’s producers declare very high robot working time without failures, but there are fewer publications about the real robot reliability and about occurring failures. Some surveys show that not every robot user has monitoring and collects data about robot failures. The practice show, that the most unreliable components are in the robot’s equipment, including grippers, tools, sensors, wiring, which are often custom made for different purposes. The lifecycle of a typical industrial robot is about 10-15 years, because the key mechanical components (e.g. drives, gears, bearings) are wearing out. The key factor is the periodical maintenance following the manufacturer’s recommendations. After that time, a refurbishment of the robot is possible, and it can work further, but there are also new and better robots from modern generation.

Keywords: Industrial robot;Reliability; Failures; Availability; Maintenance; Safety; MTTF; MTBF; MTTR; DTDTRF

Introduction

Nowadays, one can observe the increasing use of automation and robotization, which replaces human labor. New applications of industrial robots are widely used especially for repetitive and high precision tasks or monotonous activities demanding physical exertion (e.g. welding, handling). Industrial robots have mobility similar to human arms and can perform various complex actions like a human, but they do not get tired and bored. In addition, they have much greater reliability then human operators. The problem of industrial robot reliability is like machine reliability and is well known and described in the literature, but because of the complexity of robotic systems is also much more complex and is connected with safety requirements and specific robot related problems (near failure situations, hardware failures, software failures, singularity, human errors etc.). Safety is very important, becausethere were many accidents at work with robots involved, and some of them were deadly. Accidents were caused rather more often by human errors than by failures of the robots.

The research about robot reliability was started in 1974 by Engleberger, with publication, which is a summary of three million hours of work of the first industrial robots–Unimate[1]. A very comprehensive discussion over the topic is presented by Dhillon in the book, which covers the problems of robot reliability and safety, including mathematical modelling of robot reliability and some examples[2]. An analysis of publications on robot reliability up to 2002 is available in Ref. Dhillon et al.[3], and some of the important newer publications on robot reliability and associated areas are listed in the book [4].The modern approach to reliability and safety of the robotic system is presented in the book, which includes Robot Reliability Analysis Methods and Models for Performing Robot Reliability Studies and Robot Maintenance[5]. The reliability is strongly connected with safety and productivity, therefore other researches include the design methods of a safe cyber physical industrial robotic manipulator and safety-function design for the control system or simulation method for human and robot related performance and reliability[6-7]. There are fewer publications about the real robot reliability and about occurring failures [8]. The surveyshows that only about 50 percent of robot users have monitoring and collect data about robot failures.

Failure analysis of approximately 200 mature robots in automated production lines, collected from automotive applications in the UK from 1999, is presented in the article, considering Pareto analysis of major failure modes. However, presented data did not reveal sufficiently fine detail of failure history to extract good estimates of the robot failure rate[9-10].

In the article11. Sakai et al.[11], the results of research about robot reliability at Toyota factory are presented. The defects of 300 units of industrial robots in a car assembly line were analyzed, and a great improvement in reliability has been achieved. The authors consider as significant activities that have been driven by robot users who are involved in the management of the production line. Nowadays, robot manufacturers declare very high reliability of their robots [12]. The best reliability can be achieved by the robots with DELTA and SCARA configuration. This is connected with lower number of links and joints, compared to other articulated robots. Because each additional link with serial connection causes an increase of the unreliability factors, therefore, some components are connected parallel, especially in the Safety Related Part of the Control System (SRP/CS), which have doubled number of some elements, for example emergency stops. Robots are designed in such way that any single, reasonably foreseeable failure will not lead to the robot’s hazardous motion [13].Modern industrial robots are designed to be universal manipulating machines, which can have different sort of tools and equipment for specific types of work. However, the robot’s equipment is often custom made and may turn out to be unreliable as presented in, therefore, the whole robotic system requires periodic maintenance, following to the manufacturer’s recommendations [14-15]. operators and robots in cooperative tasks, therefore, the safety plays a key role. Safety can be transposed in terms of functional safety addressing the functional reliability in the design and implementation of devices and components that build the robotic system [16].

Robot Reliability

The reliability of objects such as machines or robots is defined as the probability that they will work correctly for a given time under defined working conditions. The general formula for obtaining robot reliability is [2]:

Where:

Rr(t) is the robot reliability at time t,

λr(t) is the robot failure rate.

In practice, for description of reliability, in most cases the MTTF (Mean Time to Failure) parameter is used, which is the expected value of exponentially distributed random variable with the failure rate λr [2].

In real industrial environments, the following formula can be used to estimate the average amount of productive robot time, before robot failure [2]:

Where:

PHR – is the production hours of a robot,

NRF – is the number of robot failures,

DTDTRF – is the downtime due to robot failure in hours,

MTTF – is the robot mean time to failure.

In the case of repairable objects, the MTBF (Mean Time Between Failures), and the MTTR (Mean Time to Repair) parameters, can be used.

The reliability of the robotic system depends on the reliability of its components. The complete robotic workstation includes:

A. Manipulation unit (robot arm),

B. controller (computer with software),

C. equipment (gripper, tools),

D. workstation with workpieces and some obstacles in the robot working area,

E. safety system (barriers, curtains, sensors),

F. human operator (supervising, set up, teaching, maintenance).

The robot system consists of some subsystems that are serially connected (as in the Figure 1) and have interface for communication with the environment or teaching by the human operator.The robot arm can have different number of links and joints N. Typical articulated robots have N=5-6joints as in the Figure 2, but more auxiliary axes are possible.

For serially connected subsystems, each failure of one component brings the whole system to fail. Considering complex systems, consisting of n serially linked objects, each of which has exponential failure times with rates λi, i= 1, 2, …, n, the resultant overall failure rate λSof the system is the sum of the failure rates of each element λi[2]:

Moreover, the system MTBFS is the sum of inverse MTBFi, of linked objects:

There are different types of failures possible:

A. Internal hardware failures (mechanical unit, drive, gear),

B. Internal software failures (control system),

C. External component failures (equipment, sensors, wiring),

D. Human related errors and failures that can be:

a. Dangerous for humans (e.g. unexpected robot movement),

b. Non-dangerous, fail-safe (robot unable to move).

Also possible are near failure situations and robot related problems, which require the robot to be stopped and human intervention is needed (e.g. recalibration, reprograming).Because machinery failures may cause severe disturbances in production processes, the availability of means of production plays an important role for insuring the flow of production. Inherent availability can be calculated with the formula 7 [2].

For example, the availability of Unimate robots was about 98 % over the 10-years period with MTBF=500h and MTTR=8 hours [2].

The reliability of the first robot generation represents the typical bathtub curve (as in Figure3), with high rate of early “infant mortality” failures, the second part with a constant failure rate, known as random failures and the third part is an increasing failure rate, known as wear-out failures (it can be described with the Weibull distribution).

Therefore, the standard [17] was provided, in order to minimize testing requirements that will qualify a newly manufactured (or a newly rebuilt industrial robot) to be placed into use without additional testing. The purpose of this standard is to provide assurance, through testing, that infant mortality failures in industrial robots have been detected and corrected by the manufacturer at their facility prior to shipment to a user. Because of this standard, the next robot generation has achieved better reliability, without early failures, with MTBF about 8000 hours [16].In the articleSakai&Amasaka[11], the results of research about robot reliability at Toyota are presented. Great improvement was achieved with an increase of the MTBF to about 30000 hours.

Nowadays, robot manufacturers declare an average of MTBF = 50,000 - 60,000 hours or 20 - 100 million cycles of work [12]. The best reliability is achieved by the robots with SCARA and DELTA configuration. This is connected with lower number of links and joints, compared to other articulated robots.Some interesting conclusions from the survey about industrial robots conducted in Canada in year 2000 are as follows [9]:

A. Over 50 percent of the companies keep records of the robot reliability and safety data,

B. In robotic systems, major sources of failure were software failure, human error and circuit board troubles from the users’ point of view,

C. Average production hours for the robots in the Canadian industries were less than 5,000 hours per year,

D. The most common range of the experienced MTBF was 500–1000h (from the range 500-3000h)

E. Most of the companies need about 1–4h for the MTTR of their robots (but also in many cases the time was greater than 10h or undefined).

The current industrial practice show that the most unreliable components are in the robot’s equipment, including grippers, tools, sensors, wiring, which are often custom made for different purposes. This equipment can be easily repaired by the robot user’s repair department. But the failure of critical robot component requires intervention of the manufacturer service and can take much more time to repair (and can be counted in days). Therefore, for better performance and reliability of the robotic system, periodic maintenance is recommended.

Robot Maintenance

Three basic types of maintenance for robots used in industry are as follows [4]:

Preventive maintenance

This is basically concerned with servicing robot system components periodically (e.g. daily, yearly. …)

Corrective maintenance

This is concerned with repairing the robot system whenever it breaks down.

Predictive maintenance

Nowadays, many robot systems are equipped with sophisticated electronic components and sensors; some of them are capable of being programmed to predict when a failure might happen and to alert the concerned maintenance personnel (e.g. self-diagnostic, singularity detection).Robot maintenance should be performed, following to the robot manufacturer’s recommendations, which are summarized in the Table 1[15]. Preventive maintenance should be provided before each automatic run, including self-diagnostic of the robot control system, visual inspection of cables and connectors, checking for oil leakage or abnormal signals like noise or vibrations. The replacement of the battery, which powers the robot’s positional memory, is needed yearly. If the memory is lost, then remastering (recalibration, synchronization) is needed.Replenishing the robot with grease every recommended period is needed to prevent the mechanical components (like gears) from wearing out. Special greases are used for robots (e.g. Moly White RE No.00) or grease dedicated for specific application like for the food-industry. Every 3-5 years a fully technical review (overhaul) with replacement of filters, fans, connectors, seals, etc. is recommended.

Performing daily inspection, periodic inspection, and maintenance can keep the performance of robots in a stable state for a long period. The lifecycle of typical robot is about 10-15 years, because the wear of key mechanical components (drives, gears, bearings, brakes) causes backlash and positional inaccuracy. After that time a refurbishment of the robot is possible, and it can work further for long time. Refurbished Robots are also called remanufactured, reconditioned, or rebuilt robots.

Conclusion

Nowadays modern industrial robots have achieved high reliability and functionality;therefore, they are widely used. This is confirmed by more than one and half million of robots working worldwide. According to the probability theory, in such large robot population the failures of some robots are almost inevitable. The failures are random, and we cannot predict exactly where and when, they will take place. Therefore, the robot users should be prepared and should undertake appropriate maintenance procedures. This is important, because industrial robots can highly increase the productivity of manufacturing systems, compared to human labor, but every robot failure can cause severe disturbances in the production flow,therefore periodic maintenance is required, in order to prevent robot failures. High reliability is also important for the next generation of collaborative robots, which should work close to human workers, and safety must be guaranteed without barriers. Also, some sorts of service robots, which should help nonprofessional people (e.g. health care of disabled people) must have high reliability and safety. There have already been some accidents at work, with robots involved, therefore, the next generation of intelligent robots should be reliable enough to respect the Asimov’s laws and do not hurt people, even if they make errors and give wrong orders.

For More Open Access Journals Please Click on: Juniper Publishers

Fore More Articles Please Visit: Robotics & Automation Engineering Journal

0 notes

Text

On the Alternatives of Lyapunov’s Direct Method in Adaptive Control Design- Juniper Publishers

Abstract

The prevailing methodology in designing adaptive controllers for strongly nonlinear systems is based on Lyapunov’s PhD Thesis he defended in 1892 to study the stability of motion of systems for the solution of the equations of motion of which no closed form analytical solutions exist. The adaptive robot controllers developed in the nineties of the 20thcentury guarantee global (often asymptotic) stability of the controlled system by using his ingenious Direct Method that introduces a Lyapunov function for the behavior of which relatively simple numerical limitations have to be proved. Though for various problem classes typical Lyapunov function candidates are available, the application of this method requires far more knowledge than the implementation of some algorithm. Besides requiring creative designer’s abilities, it often requires too much because it works with satisfactory conditionsinstead of necessary and satisfactoryones. To evade these difficulties, based on the firm mathematical background of constructing convergent iterative sequences by contractive maps in Banach spaces, an alternative of Lyapunov’s technique was so introduced for digital controllers in 2008 that during one control cycle only one step of the required iteration was done. Besides its simplicity the main advantage of this approach was the possible evasion of complete state estimation that normally is required in the Lyapunov function-based design. Though the convergence of the control sequence can be guaranteed only within a bounded basin, this approach seems to have considerable advantages. In the paper the current state of the art of this approach is briefly summarized.

Keywords: Adaptive control; Lyapunov function; Banach space; Fixed point lteration

Abbrevations: AC: Adaptive Control; AFC: Acceleration Feedback Controller; AID: Adaptive Inverse Dynamics Controller; CTC: Computed Torque Control; FPI: Fixed Point Iteration; MRAC: Model Reference Adaptive Control; OC: Optimal Control; PID:Proportional, Integrated, Derivative; RARC: Resolved Acceleration Rate Control; RHC: Receding Horizon Controller;SLAC: Slotine-Li Adaptive Controller;

Introduction

There is a wide class of model-based control approaches in which the available approximate dynamic model of the system to be controlled is “directly used” without “being inserted” into the mathematical framework of “Optimal Control” (OC). A classical example is the “Computed Torque Control” (CTC) for robots [1]. However, in the practice we have to cope with the problem of the imprecision (very often incompleteness) of the available system models (in robotics e.g. [1,2], modeling friction phenomena e.g. [3-7], in life sciences as modeling the glucose-insulin dynamics e.g. [8-11] or in anesthesia control e.g. [12-14]). Modeling such engines as aircraft turbojet motors is a quite complicated task that may need multiple model approach [15-18]. Further practical problem is the existence and the consequences of unknown and unpredictable “external disturbances”. A possible way of coping with these practical difficulties is designing “Adaptive Controllers” (AC) that somehow are able to observe and correct at least the effects of the modeling imprecisions by “learning”. Depending on the above available information on the model various adaptive methods can be elaborated. If we have precise information on the kinematics of a robot and only approximate information is available on the mass distribution of a robot arm made of rigid links the exact model parameters can be learned as in the case of the “Adaptive Inverse Dynamics” (AID) and the “Slotine-Li Adaptive Controller” (SLAC) for robots that are the direct adaptive extensions of the CTC control. An alternative approach is the adaptive modification of the feedback gains or terms [19]. The “Model Reference Adaptive Control” (MRAC) has double “intent”: a) it has to provide precise trajectory tracking, and b) for an outer, kinematics-based control loop they have to provide an illusion that instead of the actually controlled system, a so called “reference system” is under control (e.g. [20-22]).

The traditional approaches in controller design for strongly nonlinear systems are based on the PhD thesis by Lyapunov [23] that later was translated to Western languages (e.g. [24]). (In this context “strong nonlinearity” means that the use of a “linearized system model” in the vicinity of some “working point” is not satisfactory for practical use.) In Lyapunov’s “2nd” or “Direct Method” a Lyapunov function has to be constructed for the given particular problem (typical “candidates” are available for typical “problem classes”), and non-positiveness of the time-derivative of this function has to be proved. Besides the fact that the creation of the Lyapunov function is not a simple application of some algorithm –it is rather some creative art–, this method has various drawbacks as a) it works with “satisfactory conditions” instead of “necessary and satisfactory conditions” (i.e. often it requires too much as guaranteeing really not necessary conditions), b) its main emphasis is on global (asymptotic) stability of the motion of the controlled system without paying too much attention to the “initial” or “transient” phase of the controlled motion (for instance in life sciences a “transient” fluctuation can be lethal).

To cope with these difficulties alternatives of the Lyapunov function-based adaptive design were suggested in [25] in which the primary design intent is keeping at bay the initial “transients” by turning the task of finding the necessary control signal to iteratively so solving a fixed point problem [“Fixed Point Iteration” (FPI)] that in each digital control step only one step of the appropriate iteration can be realized. The mathematical antecedents of this approach were established in the 17th century (e.g. [26-28]), and its foundations in 1922 were extended to quite complicated spaces by Stefan Banach [29,30]. In [25] the novelty was the application of this approach to control problems. In contrast to the “traditional” “Resolved Acceleration Rate Control” (RARC) in which in the control of a 2nd order physical system only lower order derivatives or tracking error integrals are fed back (e.g. [19,31-33]) in this approach the measured “acceleration” signals are also used as in the “Acceleration Feedback Controllers” (AFC) (e.g. [34-38]).

In general, the most important “weak point” of the FPI-based approach is that it cannot guarantee global stability. The generated iterative control sequences converge to the solution of the control task only within a bounded basin that in principle can be left. To avoid this problem heuristic tuning rules were introduced for one of the little numbers of the adaptive parameters in [39-41]. In [42] essentially the same method was introduced in the design of a novel type of MRAC controllers the applicability of which was investigated by simulations for the control of various systems (e.g. [43-46]). Observing the fact that in the classical, Lyapunov function-based solutions as the AID and SLAC controllers the parameter tuning rule obtained from the Lyapunov function has a simple geometric interpretation that is independent of the Lyapunov function itself, the FPI-based solution was combined with the tuning rule of the original solutions used for learning the “exact dynamic parameters” of the controlled system. Alleviated from the burden of necessarily constructing some easily treatable quadratic Lyapunov function, the feedback provided by the FPIbased solution was directly used for parameter tuning. This solution resulted in precise trajectory tracking even in the initial phase of the learning process in which the available approximate model parameters still were very imprecise [47,48]. In the present paper certain novel results are summarized on the further development of the FPI-based approach.

Discussion and Results

The structure of the FPI-based adaptive control

The block scheme of the FPI-based adaptive controller is given in Figure 1 for a 2nd order dynamical system as e.g. a robot [48]. In this case the 2nd time-derivative of the generalized coordinates (joint coordinates). qcan be instantaneously set by the control torque or force Q On this basis, in the kinematic block an arbitrary desired joint acceleration can be designed that can drive the tracking error N q (t) − q(t) to 0 if it is realized. In the practice this joint acceleration cannot be realized due to the imprecisions in the dynamic model the CTC controller uses for the calculation of the necessary forces. Therefore, instead introducing this signal into the Approximate Model to calculate the necessary force its deformed version, is introduced into it. The necessary deformation iteratively is produced in the form of a sequence that is initiated by it, i.e. by During one digital control step one step of the iteration can be realized. If there are no special time-delay effects in the system, the contents of the delay boxes in Figure 1 exactly correspond to the cycle time of the controller Δt The “chain of operations” resulting in an observed realized response q(t) for the input mathematically approximately can be considered as a response since –though it depends on q and q − only slowly varies in comparison to that quite quickly can be modified. In the Adaptive Deformation Block of Figure 1 a function is used as in which [49]. Since due to the proportional, integral and derivative error feedback terms varies only slowly, we have an approximation as Regarding the convergence of this iteration, we have to take it into account that a Banach Space (accidentally denoted by B is a complete, linear, normed metric space. It is a convenient modeling tool that allows the use of simple norm estimations. Its completeness means that each self-convergent or Cauchy sequence has a limit point within the space. A mapping F :β β is contractive if ∃ a real number 0 ≤ K < 1 so that, It is easy to show that the sequence generated by a contractive map as is a Cauchy sequence: in the norm estimation given in (1)∀Lε in high order powers of K occur as n → ∞ therefore Due to the completeness of arbitrary element of the sequence n x according to (2) it holds that .

Consequently, it is enough to guarantee that the function F(.) is contractive, since in this case the sequence converges to the fixed point of this function if it is so constructed that its fixed point is the solution of the control task.

Construction of the adaptive function

In the original solution in [25] (3) was suggested for the special case qε IRwith three adaptive parameters Kc, Bc, and Ac.

Really, when we just have the solution of the control task and it is obtained that that is the solution is a fixed point. To obtain convergence in the vicinity of the fixed consider the 1st order Taylor series approximation as

leads to the approximation

On the basis of (5) it is easy to set the adaptive parameters for convergence: by choosing a great parameter and a small Ac it can be achieved that therefore the mapping is contractive and the sequence converges to the solution. The speed of convergence depends on setting Ac, and too great value can cause leaving the region of convergence.

For qε IRn (multiple variable systems) a different construction was introduced in [50,51] the convergence properties of which were more lucid than that of the multiple variable variant of (3):

in which the expression can be identified as the “response error in time t”, and with the Frobenius norm corresponds to the unit vector that is directed into the direction of the response error, ζ : IR IR is a differentiable contractive map with the attractive fixed point ( )* * ζ x = x and c Aε IR is an adaptive control parameter. By using the same argumentation with the1st order Taylor series approximation it was shown in [52] that if the real part of each eigenvalue of is simultaneously positive or negative, an appropriate Ac parameter can be selected that guarantees convergence.

in which Qε IR2 denotes the control force and qε IR2 is the array of the generalized coordinates of the controlled system.

The parameter 1 σ , and 2 σ > 0 “modulate” the springs’ stiffness, the direction of the spring force is calculated by the use of the “signum” function as sign ( ) 1 01 q − L while its absolute value is The approximate and exact model parameter values are given in Table 1.

In the Kinematic Block for the integrated error the prescribed “tracking strategy” was that lead to a PID-type feedback that choice guarantees the convergence in the simulations ∧ = 6s−1 was chosen with ζ (x) = atanh (tanh (x + D) / 2),D = 0.3 in (6). The choice 5 10 1 c A = − × − resulted in good convergence. The Figure2–6 illustrate the effects of using the adaptive deformation. It is evident that the tracking precision was considerably improved without any chattering effect that are typical in the also simple Sliding Mode / Variable Structure Controllers (e.g. [53,54]. Figure 5 reveals that quite different control forces were applied in the non-adaptive and in the adaptive cases.

The essence of the adaptivity is revealed by Figure 6. In the non-adaptive case considerable PID corrections are added totherefore it considerably differs fromthat is identical to in the lack of adaptive deformation. However, the difference between the desired and the realized 2nd time-derivatives are quite considerable if no adaptive deformation is applied. In contrast to that, in the adaptive caseis in the vicinity of because only small PID corrections are needed if the trajectory tracking is precise. This desired value is very close to the realized 2nd time derivatives that considerably differ from the adaptively deformed value. That is, quite considerable adaptive deformation was needed for precise trajectory tracking due to the great modeling errors.

Further Possible Applications and Development

The applicability of the FPI-based adaptive control design methodology was investigated in various potential fields of application. In 2012 in [55] an adaptive emission control of freeway traffic was suggested by the use of the quasistationary solutions of an approximate hydrodynamic traffic model. In [56] an FPI-based adaptive control problem of relative order 4 was investigated. In [57] FPI-based control of the Hodgkin-Huxley Neuron was considered. In [58] the possible regulation of Propofol administration through wavelet-based FPI control in anaesthesia control was investigated.

In [59] the application of the FPI-based control in treating patients suffering from “Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus” was studied. The simplicity of the FPI-based method opened new prospects in the possible design of adaptive optimal controllers. In [60] the contradiction between the various requirements in OC was resolved in the case of underactuated mechanical systems in the following manner: instead constructing a “cost function contribution” to each state variable the motion of which needed control, consecutive time slots were introduced within which only one of the state variables was controlled with FPI-based adaptation. (The different sections may correspond to different relative order control tasks.) In [61] it was pointed out that the FPI-based control can be easily combined with the mathematical framework of the “Receding Horizon Controllers” (RHC) (e.g. [62]). (A combination with the Lyapunov function-based adaptive approach would be far less plausible and simple.) In [49] the applicability of this approach was introduced into the control of systems with time-delay. The possibility of fractional order kinematic trajectory tracking prescription in the FPI-based adaptive control was studied, too [63].

In [64] its applicability was investigated in treating angiogenic tumors. In [65,66] further simplification of the adaptive RHC control was considered in which the reduced gradient algorithm was replace by a FPI in finding the zero gradient of the “Auxiliary Function” of the problem. In [67] the applicability of the method was experimentally verified in the adaptive control of a pulse-width modulation driven brushless DC motor that did not have satisfactory documentation (FIT0441 Brushless DC Motor with Encoder and Driver) and was braked by external forces simply by periodically grabbing the rotating shaft by one’s two fingers. The solution was based on a simple Arduino UNO microcontroller with embedding the adaptive function defined in (3) into the motor’s control algorithm. In spite of using 2nd time-derivatives in the feedback no special noise filtering was applied. The measured and computed data was visualized by a common laptop. As it can be seen in Figure 7, the rotational speed was kept at almost constant (in spite of the very noisy measurement data), and the adaptive deformation and the control signal were well adapted to the external braking forces in harmony with the simulation results belonging to the “Illustrative Example” in subsection 2.3.

Figure 7: The experimental setup used for the verification of the FPI-based adaptive control in the case of a pulse-width modulated brushless electric DC motor; The nominal and the realized rotational speed (the average of the whole data set was 59:9383rpm, the nominal constant value was 60rpm); The “Desired” and adaptively “Deformed” 2nd timederivatives of the rotational speed; The control signal (from [67], courtesy of Tamás Faitli) In [68] the novel adaptive control approach was considered from the side of the Lyapunov function-based technique and it was found that it can be interpreted as a novel methodology that is able to drive the Lyapunov function near zero and keeping it in its vicinity afterwards. On this basis a new MRAC controller design was suggested in [69] that has similarity with the idea of the “Backstepping Controller” [70,71].

Conclusion

The FPI-based adaptive control approach was introduced at the Óbuda University with the aim of evading the mathematical difficulties and restrictions, furthermore the information need related to the traditional Lyapunov function-based design. Its main point was the transformation of the control task into a fixed-point problem that was iteratively solved on the firm mathematical basis of Banach’s fixed point theorem. In the center of the new approach, instead of the requirement of global stability, as the primary design intent, precise realization of a kinematically (kinetically) prescribed tracking error relaxation was placed. In contrast to the traditional soft computing approaches as fuzzy, neural network and neuro-fuzzy solutions that normally apply huge structures with ample number of the parameters of the universal approximators of the continuous multiple variable functions on the basis of Kolmogorov’s approximation theorem (e.g. [72-74]) this approach has only a few independent adaptive parameters that can be easily set and one of them can be tuned for maintaining the convergence of the control algorithm. It was shown that the simplicity of this approach allows its combination with more “traditional” approaches as that learning the exact model parameters of the controlled system and at various levels of the optimal controllers as the RFC control. On the basis of ample simulation investigations, it can be stated that the suggested approach has wide area of potential applications (in the control of mechanical devices, in life sciences, traffic control, etc.) where the presence of essential nonlinearities, the lack of precise and complete system models, and limited possibilities for obtaining information on the controlled system’s state are present as main difficulties. It seems to be expedient to invest more efforts into experimental investigations.

Acknowledgement

The Authors express their gratitudes to the Antal Bejczy Center for Intelligent Robotics, and the Doctoral School of Applied Informatics and Applied Mathematics for supporting their work.

For More Open Access Journals Please Click on: Juniper Publishers

Fore More Articles Please Visit: Robotics & Automation Engineering Journal

0 notes

Text

Beauty, A Social Construct: The Curious Case of Cosmetic Surgeries | Juniper Publishers

Juniper Publishers-Open Access Journal of Dermatology & Cosmetics

Authored by Vandana Roy

Abstract

In this article we deconstruct the social norm of beauty and cosmetic beauty treatment, an issue that is seldom discussed in medical circles and is often lost to popular rhetoric. In doing so, we also reflect on the institutionalized system of social conditioning.

A Historical Perspective

Cosmetic surgery, as with reconstructive surgery, has its roots in plastic surgery (emerging from the Greek word ‘plastikos’, meaning to mold or form). The practice of surgically enhancing or restoring parts of the body goes back more than 4000 years. The oldest accounts of rudimentary surgical procedures is found in Egypt in the third millennia BCE. Ancient Indian texts of 500 BCE outline procedures for amputation and reconstruction. The rise of the Greek city-states and spread of the Roman Empire is also believed to have led to increasingly sophisticated surgical practices. Throughout the early Middle Ages as well, the practice of facial reconstruction continued. The fifth century witnessed a rise of barbarian tribes and Christianity and the fall of Rome. This prevented further developments in surgical techniques. However, medicine benefited from scientific advancement during the Renaissance, resulting in a higher success rate for surgeries. Reconstructive surgery experienced another period of decline during the 17th century but was soon revived in the 18th century. Nineteenth century provided impetus to medical progress and a wider variety of complex procedures. This included the first recorded instances of aesthetic nose reconstruction and breast augmentation. Advancements continued in the 20th century and poured into present developments of the 21st century.

Go to

Desires and Demands in Contemporary Times

In recent years, the volume of individuals seeking cosmetic procedures has increased tremendously. In 2015, 21 million surgical and nonsurgical cosmetic procedures were performed worldwide. In the United Kingdom specifically, there has been a 300% rise in cosmetic procedures since 2002. The year 2016 witnessed a surge in the number of such treatments with the United States crossing four million operations. Presently, the top five countries in which the most surgical and nonsurgical procedures are performed are the United States, Brazil, South Korea, India, and Mexico. Such demand can be viewed from different perspectives. At one end it is a product of scientific progress, growing awareness, economic capacities and easier access and on the other, something on the lines of a self-inflicted pathology. This article dwells on the latter and attempts to address a deep-rooted problem of the social mind.

Lessons from History

History is witness to a number of unhealthy fashion trends, many of which today appear extremely irrational and even cruel. Interestingly, the common thread connecting all of them is the reinforcement of social norms and stereotypes. Forms of socialization which lie at the intersection of race, class and gender-based prejudices. To elaborate, hobble skirts and chopines restricted women’s movement and increased their dependence on others. Corsets deformed body structures, damaged organs and led to breathing problems. The Chinese practice of binding women’s feet to limit physical labor was regarded as a sign of wealthiness. Dyed crinolines and 17th century hairstyles made people vulnerable to poisoning and fire related injuries. Usage of makeup made of lead and arsenic, eating chalk and ‘blot letting’, reflected a blatantly racist obsession with white and pale skin. Lower classes faked gingivitis to ape tooth decays of the more privileged who had access to sugar. Furthermore, other practices like tooth lacquering, radium hair colors, mercury ridden hats, usage of belladonna to dilate pupils and even men wearing stiff high collars, all furthered societal expectations and notions of class superiority. Till the 1920’s, there was rampant usage of side lacers to compress women’s curves. Even today many ethnic tribes continue with practices which inflict bodily deformations. In the urban context as well, trends like high heels, skinny jeans and using excessive makeup dominate the fashion discourse. Cosmetic procedures are the latest addition to the kitty.

The Social Dilemma

What is it that leads the ‘intelligent human’ of today to succumb to archaic and regressive notions of beauty? What motivates them to risk aspects of their lives to cater to selflimiting rules of ‘acceptance’? The surprising part is that this anomaly is often placed in the illusory realm of ‘informed consent’. In common parlance, ‘to consent’ implies voluntary agreement to another’s proposal. The word ‘voluntary’ implies ‘doing, giving, or acting of one’s own free will.’ However, when the entire socio-cultural set up and individual attitudes validate certain behaviors, there is very less space left for an alternate narrative. Let alone free will.

Pierre Bourdieu once argued that nearly all aspects of taste reflect social class. Since time immemorial, societal standards of beauty have provided stepping stones to social ascent and class mobility. Better ‘looking’ individuals are considered to be healthier, skillfully intellectual and economically accomplished in their lives. Such an understanding stems from well entrenched stereotypes in complete disregard of individual merit and fundamental freedoms. An inferiority complex coupled with external pressures and self imposed demands, subconsciously coerce individuals into a vicious cycle of desire or rejection. Active and aggressive media has played a key role in forming societal perceptions of what is attractive and desirable. In addition, lifestyle changes reflect an image obsessed culture, reeking of deep-rooted insecurities. At the root of a submissive and conformist attitude lies a subconscious mind lacking selfesteem and self-worth. People continue to look for remedies in the wrong places. The only difference is that corsets and blot letting have given way to surgeries and cosmetic products. The biggest question is, how have ideas otherwise seen as deviant, problematic and inadequate retained control over minds of millions of individuals?

A Gendered Culture

‘Beauty’ is understood as a process of ongoing work and maintenance, its ‘need’ unfairly tilted towards the fairer sex. History has demonstrated the impact of dangerous beautification practices on women. Contemporary ideals aren’t far from reaching similar outcomes. Today, there is a powerful drive to conform to the pornographic ideal of what women should look like. There has been a growth in the number of adolescents who take to cosmetic surgeries to become more ‘perfect’. In many countries, the growth of the “mommy job” has provoked medical and cultural controversies. Presumably there is an underlying dissatisfaction which surgery does not solve. Furthermore, where does the disability dimension fit in here? What happens to the ‘abnormal’ when the new ‘normal’ itself is skewed? For those with dwarfism and related disorders, new norms become even more burdensome.

The massive pressure to live up to some ideal standard of beauty, particularly for women, reeks of patriarchal remnants of a male dominated society. This kind of conformity further nurtures objectification and sexualization, reducing women to the level of ‘chattel’ to feed the male gaze. There is a also a power struggle at play where biased standards help maintain the unequal status quo. Today, there is idolization of celebrities, beauty pageants and advertisements by cosmetic companies over sane medical advice. They set parameters of size, color and texture to be followed by the world at large. Moreover, people who deviate from such norms are made to feel stigmatized or ostracized from social spheres. The existence of male-supremacist, ageist, hetero sexist, racist, class-biased and to some extent, eugenicist standards reflect a failure of society as a whole. It is thus high time that we revisit and deconstruct skewed standards of beauty.

Mind Over Matter: Psychological Dimensions

Culturally imposed ideals create immense pressure of conformity. Consequently, they have been successful in engendering insecurities via their influence on perception of self and body image. Such perceptions often become distorted and discordant with reality, leading to serious psychological disorders. One such disorder is the body dysmorphic disorder (BDD). This is a psychiatric disorder characterized by preoccupation with an imagined defect in physical appearance or a distorted perception of one’s body image. It also has aspects of obsessive-compulsiveness including repetitive behaviors and referential thinking. Such preoccupation with self-image may lead to clinically significant distress or impairment in social and occupational functioning. With reference to cosmetic surgeries, patients with BDD often possess unrealistic expectations about the aesthetic outcomes of these surgeries and expect them to be a solution to their low self-confidence. Many medical practitioners who perform cosmetic surgery believe themselves to be contributing towards construction of individual identity as well. The notion that beauty treatments can act in much the same way as psychoanalysis has led countries like Brazil to open its gate of cosmetic procedures to lower income groups. This happens while the country continues its battles with diseases like tuberculosis and dengue. The philosophy behind such ‘philanthropy’ is that ‘beauty is a right’ and thus should be accessible to all social groups. While on one hand we may applaud such efforts of creating a more ‘egalitarian’ social order, on the other hand it is hard to overlook the self-evident undercurrents of social prejudice and capitalistic propaganda.

Medicalization of Beauty

Traditional notions of beauty embody a kind of hierarchy and repression which alienate individual agency and renders them as powerless victims. Such is the societal pressure which normalizes cosmetic procedures and subverts serious health effects. These include adverse effects due to cosmetic fillers like skin necrosis, ecchymosis, granuloma formation, irreversible blindness, anaphylaxis among others. Other dangers like heightened susceptibility to cancer and increased suicide rates. However, patients are often unaware of the risks which are hidden behind a veil of expectations and reassurances. Furthermore, quackery and inadequate standards such as lack of infection control also compound the problems of this under regulated field.

Role of Stakeholders

At the heart of any successful social transformation lies the power of united will and collective action. Thus, the consolidated and sustained effort by all stakeholders is the key to realizing an ecosystem conducive to tackle negative social norms. At the outset, government regulation is needed with respect to cosmetic procedures and the cosmetics industry. These regulations should encompass all private and public avenues and should also work against misleading advertising. Spreading awareness is the key to a better informed society. The state should fund and run specialized awareness sessions pertaining to psychological problems and aid mechanisms, gender sensitization as well as those aiming at spiritual and introspective personal development of individuals. NGO’s, medical professionals, academicians and members of the civil society, must come together to eradicate forms of social discrimination which undermine social institutions and individual agency around the world. This would help facilitate discussion, data collection, coalition building, and action that may eventually lead to behavioral changes.

Aesthetic surgery today seems to be passing through an ethical dilemma and an identity crisis. And rightly so for it strives to profit from an ideology that serves only vanity, bereft of real values. Nevertheless, there are exceptional cases where medical-aesthetic inputs have been vital in restoring morale by subverting stigmatization.

The Way Ahead

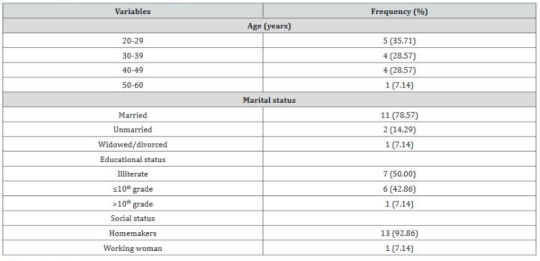

Beauty is unfair. The ‘attractive’ enjoy powers gained without merit. The perfectionist in humans seeks outward validation of external beauty over inner virtues. Scientific progress and an increase in human expertise to manipulate natural phenomena has paved the way for these desires to become a reality. There is no denying that advances in plastic and reconstructive surgery have revolutionized the treatment of patients suffering from disfiguring congenital abnormalities, burns and skin cancers. However, the increased demand for aesthetic surgery falls short of a collective psychopathology obsessed with appearance. This article expresses trepidation about such forms of social consciousness that first generates dissatisfaction and anxiety and then provides surgery as the solution to a cultural problem.