Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Threading Purpose Through Practice: A Final Reflection on Becoming an OT

"We do not think ourselves into new ways of living; we live ourselves into new ways of thinking." – Richard Rohr

As I sit with the weight of my final undergraduate blog, I return to this quote. My journey through the UKZN Occupational Therapy curriculum and especially my time in the Kenville community taught me that transformation rarely arrives as a lightning epiphany. Instead, it shows up quietly in a child’s poor grip on a pencil, in a muddy footpath to the OT clinic, and in the youth’s laughter after a group activity. I walked into this journey thinking I was going to help the community. Honestly, the community helped me become more critical, reflective, and rooted in purpose. This is my way of closing the loop, offering not just lessons learned but a deeper inquiry into who I’ve become and what I carry forward. It is moral because it explores meaning, it is conceptual because it deals with the profession’s framework, and it is axiological because it confronts my values, the system that I operate within.

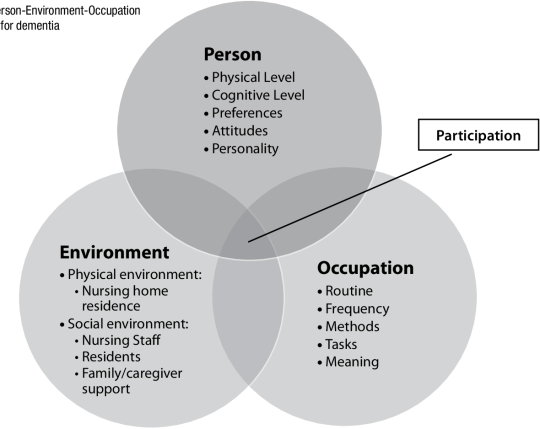

I came to Kenville armed with a lot of frameworks, including SWOT analysis, MOHO, PEOP, and community needs assessments. I was good at reciting them. However, these models didn't start to come to life until I walked around the community, past decaying roads and sidewalks and informal houses.

Above shows the environmental conditions of some parts of the Kenville community where people reside.

I remember the muddy pathway leading to the OT clinic. Clients in wheelchairs and elderly people with walking frames struggled to reach us, especially on rainy days. If access to therapy begins with a barrier, how do we expect participation to flourish? And that observation encouraged us to start collaborating with the stakeholders within the community to begin constructing a safe, paved walkway to the OT container. For me, this symbolized occupational justice in action. We weren’t providing therapy; we were shifting an unjust reality. In moments like these, OT became more than a profession. It became a philosophy of presence, a way of showing up fully, even when resources are scarce. It taught me that change does not always come from grand gestures. Sometimes, it’s a question asked in a team meeting, a suggestion to the school principal, or even a shared silence with a grieving caregiver.

As a fourth-year student, I thought I knew what OT practice required. After all, I had been tested on assessments, splinting, goniometry, and theoretical reasoning. But nothing prepared me for the emotional and logistical complexity of real-life clients in real-time chaos. One case reshaped my clinical lens. A 9-year-old girl in grade 2 couldn’t write her name or hold a pencil correctly. After speaking with the school and tracing her backstory, I learned her mother battled alcoholism, and she had essentially raised herself. I was heartbroken and furious. Not just at the system, but at myself for thinking I could fix this in one session. Instead of just assessing her fine motor skills, I advocated for her to be placed in a lower grade, giving her time to build foundational skills. This wasn’t just clinical work. It was advocacy. It was acknowledging that our work sits at the intersection of health, education, and social justice.

Above is a group of primary school learners engaging in a fine motor skills activity.

I also facilitated a Youth Expressive Group where teenagers, many facing high stress, poverty, and identity struggles, were invited to engage in storytelling, music, and art. The shift in their energy, especially the girls', was great. Through these groups, I learned that therapy doesn’t always look like a session plan. Sometimes it’s a safe space, music, and art.

Above is the expressive group showing participants engaging in a painting activity.

These experiences affirmed that my professional growth isn’t measured by technical skills alone. It’s about developing clinical humility, cultural competence, and political awareness.

“Our curriculum gave us models. But fieldwork made those models real.”

SWOT analysis, for example, seemed like a corporate planning tool until I applied it to understand why some programmes in Kenville thrived while others fell apart. It forced me to look beyond symptoms and ask better questions, such as what are the environmental enablers? What systemic gaps are being ignored? Who has the power to make decisions, and who doesn’t?

Community needs assessment taught me that real empowerment starts with co-creation, not top-down intervention. We sat with community members, not as experts, but as learners. We learned that a boy’s lack of school attendance was tied to bullying and that a mother’s missed appointments weren’t due to negligence but to a lack of transport. These insights were not in textbooks. They were born from empathy, dialogue, and listening skills that the UKZN OT curriculum thankfully encourages but that the community perfected in me.

The word “values” gets thrown around a lot in healthcare. But in the field, values are not what we write; they are what we live. Kenville tested my values in the best way. I remember one afternoon, we ran an inclusive soccer game where children with and without disabilities played together. A child with ataxic CP scored a goal with the help of his peers, and the field erupted with joy. That image stays with me, not because of what we did, but because of what it represented: inclusion, visibility, joy, and participation, which is what OT is about. My values also surfaced in frustration. Frustration at inequality. At how some schools are so under-resourced that children in Grade 3 can’t read, while others in wealthier suburbs are coding robots. I learned to let that discomfort sharpen, not paralyse me. To let it guide me toward political reflection and social responsibility.

The UKZN OT curriculum has been redesigned to promote social responsiveness, as Naidoo and Van Wyk (2016) say. Now I know the true meaning of that. It entails choosing compassion despite the tension. It entails standing up for a child outside of the session as well.

As I prepare for my community service for next year, I carry more than just a degree. I carry the stories, the smiles, the laughter, and the tears of a community that trusted me enough to let me grow among them. I know challenges await. Under-resourced placements come with limited tools, staffing shortages, and systemic delays. But I know that I am entering the space not just as a prospective graduate, but as someone who has learned to think critically, act justly, and adapt creatively. I hope to continue advocating for inclusive infrastructure, disability visibility, and youth empowerment. I plan to carry forward the reflective habits we were encouraged to develop, using journaling, supervision, and community blogs to stay grounded.

Above is a hand resting splint made by an OT student for a left CVA client using limited tools in the clinic.

Most importantly, I walk into this new chapter knowing I’m still becoming. OT is not a static profession. It is dynamic, evolving, and relational. Every client, every session, and every ethical dilemma will ask me, what do you value? I dare you to answer.

“You’ll only truly understand it when you’re in the field”, they said. They were right. But now I know that understanding is not the end. It is the beginning. And I am ready!

RESOURCES

REFERENCES

Naidoo, D., & Van Wyk, J. (2016). Exploring the transformative occupational therapy curriculum for relevance to the South African context. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy, 46(3), 10–14. https://doi.org/10.17159/2310-3833/2016/v46n3a3

Richard Rohr. (2003). Everything belongs: The gift of contemplative prayer. Crossroad Publishing.

United Nations. (2015). Sustainable development goals. https://sdgs.un.org/goals

UNESCO. (2021). Education for sustainable development: A roadmap. https://www.unesco.org/en/education

UN Women. (2022). Gender equality: Women’s rights in review 25 years after Beijing. https://www.unwomen.org/en/what-we-do

World Health Organization. (2023). Health promotion. https://www.who.int/health-topics/health-promotion

World Health Organization. (2023). Mental health and substance use. https://www.who.int/teams/mental-health-and-substance-use

0 notes

Text

Working Towards a Better Tomorrow: 5 Sustainable Development Goals in the Kenville Community

“Change begins at a community level”, a phrase that resonates deeply with my experience as an occupational therapy student working with the resilient, yet underserved, Kenville community. Settled in the heart of KwaZulu-Natal, Kenville faces complex challenges. Poverty, limited access to healthcare, under-resourced schools, youth unemployment, and environmental neglect. Yet, it is also a community full of potential.

In this blog, I reflect on five Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) that I actively strive to support in my Kenville, goals that guide my interventions and vision for inclusive, sustainable development.

SDG 3: Good Health and Well-being

This goal focuses on ensuring healthy lives, promoting well-being for all ages. It includes physical, mental, and emotional health (World Health Organization [WHO], 2023)

Promoting holistic health in Kenville is a core focus of our OT practice. Each morning, we host health promotion sessions where we engage with people in the clinic queues, raising awareness on substance use and abuse, mental health, child development, and disability. These short, accessible talks empower individuals to make informed health decisions and reduce stigma around mental illness and disability. One of our key interventions is the Youth Expressive group, which focuses on youth wellness and development. Through music, art, and storytelling, adolescents are encouraged to express their emotions, reflect on their experiences, and build resilience in a safe, supportive space.

The group also incorporates a peer education approach, where high school students are taught stress and anxiety management techniques ahead of exam periods. This helps build confidence, promotes empathy, and ensures the messages are relatable and relevant. Through these efforts, we are actively supporting both the emotional well-being and mental health literacy of the Kenville community. Thus, this aligns with the aim of the SDG.

SDG 4: Quality Education

This goal promotes inclusive, equitable, and quality education and lifelong learning opportunities for all, especially vulnerable children (UNESCO, 2021).

Many learners in Kenville encounter academic obstacles because of socioeconomic difficulties, unknown learning disabilities, or inadequate home support. To improve the fine motor and visual-motor skills of Grade 2 students, I led a small group interventions and performed screenings as part of our school-based occupational therapy program. During one group session, I came across a 9-year-old learner who, despite being in Grade 2, was unable to hold a pencil correctly and did not yet know how to read or write. This was heartbreaking. After looking into it more, I found that the child's mother battles alcoholism, which is why the child was referred from a nearby organization that helps underprivileged kids. Her lack of basic education had been neglected.

I spoke with the principal of the school about the situation and suggested that the student be put in a lower grade to build the academic and motor skills they would need before moving on.

Thus, this case demonstrated the occupational therapists advocacy role in advancing equitable education and making sure students are not positioned for failure because of systemic gaps (Case-Smith & O’Brien, 2015).

"Group of learners at Seacowlake Primary School engaging in fine motor skill activity using play dough."

SDG 5: Gender Equality

This goal aims to achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls by eliminating discrimination and promoting equal opportunities (UN Women, 2022).

Young women in the Kenville community frequently deal with low self-esteem, unequal access to opportunities, and social pressures. Our current Youth Expressive Group program focuses on the development and well-being of young people, with a particular emphasis on the empowerment of young women and girls. In addition to teaching vital social skills for overcoming everyday obstacles in relationships, school, and the larger community, the program seeks to encourage self-worth and personal goal setting. In a secure, encouraging setting, participants are encouraged to explore their identities and feelings through creative expression exercises like storytelling, music, and art.

We support inclusive participation and leadership among girls by boosting their self-esteem and encouraging self-advocacy, which increases SDG 5.

SDG 9: Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure

This goal encourages building resilient infrastructure, promoting inclusive and sustainable industrialisation, and fostering innovation (United Nations, 2015).

Limited infrastructure in Kenville affects community access to health services. A key example is the unpaved, muddy pathway leading to the OT container, which becomes dangerously slippery during rain, particularly for clients using wheelchairs, crutches, or walking frames. We are currently involved in a project to construct a proper paved walkway to ensure safe and dignified access to therapy. This infrastructure improvement will promote occupational justice by removing physical barriers to care.

This reflects how even small-scale infrastructure improvements can significantly improve access and participation for marginalised populations, thus aligning with this SDG.

" This is picture shows the place where the pavement will be built in order to facilitate accessibility"

SDG 10: Reduced Inequalities

This goal seeks to reduce inequality within and among countries by ensuring social, economic, and political inclusion of all, regardless of background or ability (United Nations, 2015)

In Kenville, people with disabilities frequently experience exclusion from play, public places, and educational spaces. By starting an inclusive soccer program and allowing disabled youth to play alongside their peers in modified settings, we actively wanted to change this. Social barriers were broken down during these sessions, allowing for visibility, teamwork, and shared joy. We lessened stigma and made inclusion possible by encouraging participation from people of all skill levels and fostering common community experiences, thereby symbolising the spirit of SDG 10 in a very real-world way.

" A group of children with OT students from UKZN playing soccer."

Conclusion

I've learned from my time in Kenville that genuine, sustainable development is achievable, participatory, and personal. I have witnessed through occupational therapy how regular actions, such as educating the youth and creating inclusive spaces, can support more important global objectives. The SDGs are living ideals that can direct good and encouraging behaviour rather than being disconnected rules.

I'm determined to work toward a society that supports everyone's access, equality, dignity, and health as I continue this journey. I've discovered that in Kenville, real change starts with action, listening, and inclusion. One person, one session, one community at a time.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

REFERENCE

Case-Smith, J., & O’Brien, J. C. (2015). Occupational therapy for children and adolescents (7th ed.). Elsevier Mosby.

S. (2021). Education for sustainable development: A roadmap. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000374802

UN Women. (2022). Progress on the Sustainable Development Goals: The Gender Snapshot 2022. https://www.unwomen.org/en/digital-library/publications/2022/09/progress-on-the-sustainable-development-goals-the-gender-snapshot-2022

United Nations. (2015). Transforming our world: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda

World Health Organization. (2023). World Health Statistics 2023: Monitoring Health for the SDGs. https://www.who.int/data/gho/publications/world-health-statistics

0 notes

Text

A Personal Reflection on the UKZN OT Curriculum and Its Preparation for PHC and Community-Based Practice

As a fourth-year occupational therapy student at the University of KwaZulu-Natal, UKZN, I’ve often heard the phrase, “You’ll only truly understand it when you’re in the field.” At first, I thought I did understand; after all, we had lectures, case studies, and even assessments that were practiced on each other. But it wasn’t until I entered my second block this year, working in a real community setting, that theory and practice began to truly connect in a meaningful and sometimes emotional way. In this blog, I want to share not only how the UKZN OT curriculum has prepared me for the demands of the community and primary health practice, but also times when I felt challenged, unprepared, and deeply inspired to do more.

When I was placed at Kenville community, a part of me was nervous. Would I be able to be truly helpful? Would the tools I had learned in class serve me in the new environment? It didn’t take long to realize that the models and frameworks we were taught, like the community needs analysis and SWOT (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats ), were not just academic tools. They are lifelines that helped me make sense of the community’s complex issues. At Kenville, I used SWOT analysis to understand why some community programs were succeeding while others struggled. For example, I looked at how limited resources in the community can threaten the implementation of certain programs. This opened my eyes to not just looking at the individual clients but also considering the environment, social structures, and how they contribute to health and participation.

These experiences align with the intentions behind the UKZN’s curriculum transformation, as reflected in the words of Naidoo and Van Wyk (2016). They explain that the OT program was deliberately restructured to ensure its relevance to the South African context, thus placing a great emphasis on social responsiveness and cultural competence, and the curriculum now seeks to develop students’ abilities to engage with real-world complexity and resource constraints, as I have experienced at the Kenville community.

In the OT 1st year, the OT curriculum at UKZN prepares students to use low-cost, easily accessible materials that can be used to build assistive devices or tools that the clients can use at home to ensure sustainability. Thus plays a big role in communities with low resources to lessen occupational barriers for people living with disabilities.

The UKZN OT curriculum gives students many opportunities to practice their skills before entering the field. I remember in our earlier years, we often conducted assessments on each other. We learned muscle testing, goniometry, splinting, etc. At that time, it felt empowering. But looking back now, I realize how different things are with real clients. When I splinted the peer, there were no contractures, no involuntary movements, and no pain. For example, in my 3rd year, I got into a community facility with limited splinting material and tools. I had to make sure that I became creative and used materials resourcefully while trying to handle the client, who was in pain and not maintaining a good position, which was challenging.

One aspect of UKZN’s OT curriculum that I deeply value is the early clinical exposure. In our first year, we shadow fourth-year students during their blocks. At the time, I didn’t fully understand what I was observing. But now, in my fourth year, I realize how important that early exposure was in shaping my understanding of what OT looks like across different settings. It built a mental framework that helped me adjust when I entered the community settings and other primary health care facilities.

This approach to clinical exposure, from shadowing to supervised practice, helps support our learning. It recognizes that becoming a competent therapist is not a one-year event but a gradual progression across multiple stages.

One of the things that sets the UKZN OT curriculum apart is its emphasis on community service after graduation. Many of the OT students are placed in rural areas where the need for healthcare is urgent and resources are scarce. This can be overwhelming, but it’s also incredibly meaningful. The curriculum, by gradually exposing us to under-resourced settings such as in the Kenville community, teaches us to be resourceful and client-centred, thus preparing us for reality.

As I prepare for my year and look toward community service, I feel both grateful and critical. Grateful for the many tools, experiences, and mentors UKZN has offered me. Critical of the areas that still need growth, such as longer community placements, better simulation for real-world complexity, and more explicit teaching on health policy and PHC systems.

To sum up, I've discovered that occupational therapy is about how we present ourselves, not just what we do. We bring the training, values, and flexibility that our curriculum introduces with us to community settings, hospital wards, or times of uncertainty and connection. The UKZN OT program can continue to produce graduates who are resilient change agents, socially sensitive, and clinically competent with continued improvement.

Additional Resources.

References.

Naidoo, D., & Van Wyk, J. (2016). Social accountability: A survey of perceptions and evidence of its expression at a South African health sciences faculty. African Journal of Health Professions Education, 8(1), 22–26. https://doi.org/10.7196/AJHPE.2016.v8i1.557

University of KwaZulu-Natal. (2020, November 18). Students bring occupational therapy closer to the community. UKZN College of Health Sciences. https://ww2.chs.ukzn.ac.za/news/students-bring-occupational-therapy-closer-to-the-community/

Pinterest. (n.d.). Cardboard prototype assistive device. Retrieved May 16, 2025, from https://za.pinterest.com/pin/16044142418025407/

Google Images. (n.d.). SWOT analysis template. Retrieved May 16, 2025, from https://images.app.goo.gl/uBQzwYfot3pgaF7J9

0 notes

Text

Mothers and Children : The Hearts of Our Nation.

In my first week at Kenville community, I did not realise how deeply maternal and child health (MCH) is important to the community. Moving from a background of theoretical knowledge, I thought I understood MCH, but Kenville taught me otherwise. The mothers I met were not just raising children, they were doing so while in poverty, unsafe housing, and with little support. And yet, they showed incredible strength. This experience has changed the way I see health and the role of occupational therapy. In this blog, I reflect on why MCH is important to society and how it influences our work as OTs, especially in communities where resources are limited, but human willingness is strong.

Maternal health and child health are not just about physical wellbeing, it’s about opportunity, dignity, and the future of our country. According to the World Health Organization (2016), healthy mothers are more likely to give birth to healthy children, and these children are more likely to attend school, participate in the economy, and break the cycle of poverty.

In South Africa, this is not always the case. Many mothers still do not have access to regular prenatal care, safe homes, or emotional support. In Kenville, during my health promotion, I encountered a mother who was stressed about her child's sudden change of behaviour after he was involved in a car accident. According to her report, the child actively socially participated with other children through play, but now he doesn’t go to play with them anymore and is always at home. According to Erik Erikson's stages of development, the child is in the initiative vs guilt stage, but with his presenting behaviour, he has regressed to the guilt stage. Thus, this resulted in occupational deprivation.

One reading that helped me understand this was Stein et al. (2014), who discussed how maternal mental health directly affects the child’s ability to form emotional attachments and regulate behaviour. Seeing this play in Kenville made me realize that supporting mothers is one of the most powerful things we can do for future generations.

This experience in Kenville disrupted my mindset. Before, I saw health as something clinical, something that is “fixed” in hospitals and clinics. But I now understand that health is also emotional, environmental, and social. The mother of the child that was mentioned above also had a 2-year-old daughter; now she struggled to build a close relationship between both children because of the older child’s situation. I recommended that she engage in play games or toys of their interest or involve both in small home chore tasks to facilitate relationship building and encourage social participation. She was pleased and motivated to try to implement the recommendations.

I’ve grown to appreciate the power of presence. Sometimes, being there, listening, advocating, and creating a safe space is more important than any textbook strategy out there. Professionally, I’ve realised that occupational therapy is not about rescuing people, but it's about walking alongside them (being a facilitator) and restoring meaning to their daily lives.

From an academic point of view, I began applying ideas from Whiteford (2000) about occupational deprivation. In Kenville, mothers are deprived not just of income but of meaningful roles such as being an emotional supporter, carer, teacher, and as monitor of the child’s development. They are mostly stuck in survival mode since they leave their children to cluster in crèches to make ends meet. Children, too, are deprived of safe spaces to play and grow, especially in the iKhwezi creche, which has up to 51 children clustered in one small room and can’t engage in play activities without colliding with one another. The area outside is not safe enough to promote outdoor play activities

Politically, I can’t overlook the structural inequalities that shape these conditions, e.g., as Kenville has predominantly informal settlements. It is not fair that some mothers can afford private clinics and formula (despite that they do get medical support from the Kenville Clinic, but its services are limited), while others can’t even access clean water. I found myself reflecting on who controls the power, who holds the resources, who gets care, and who is ignored.

Reading the Lancet Series on Maternal and Child Undernutrition (Black et al., 2013) made me realize the urgency. Poor nutrition and mental health in the first 1000 days of life have long-term impacts on cognition, behaviors, and health. We can’t just treat the symptoms; we have to address the systems. That includes housing, access to food, and maternal mental health support.

In this context, occupational therapy must adapt. In Kenville, we don’t always have the tools or space, but we do have people, relationships, and creativity.

Some of the OT strategies I found effective included

Home visits to help mothers recognize space for safer child mobility.

Parenting groups, where mothers shared stories and learned child stimulation techniques using everyday items.

Life skills sessions, where women were taught to make crafts, e.g, traditional attires or bead work, to promote both income generation and prenatal well-being.

Beyond sessions, learning to advocate for safer housing, for better clinic access, and for the inclusion of mental health in MCH programs. We are not just clinicians; we are also community builders and facilitators.

Conclusion

Working in Kenville has reminded me that maternal and child health is not just a medical issue but rather a social, political, and occupational one. If we neglect the mothers and children in our communities, we neglect our future. Occupational therapy has a deep and meaningful role in creating healthier, more just societies. As I move forward in my learning journey as an OT student , I hope this question is answered:

What would our country look like if we nurtured our mothers and children first?

Additional Resources

UNICEF South Africa: Maternal & Child Health.

SADAG South Africa Depression and Anxiety Group

Children’s Institute-University of Cape Town

Kenville Community Clinic

References

Black, Victora, C.G., Walker, S.P., et.al (2013).Maternal and child undernutrition and overweight in low-income and middle-income countries. The Lancet.

https://files.globalgiving.org/pfil/8854/pict_featured_large.jpg?t=1375811291000

https://i.pinimg.com/originals/4f/88/83/4f88839c7b9be6240f4672fcd9d5c147.jpg

Stein, A., Pearson, R.M., Goodman, S.H., et al. (2024).Effects of perinatal mental disorders on the foetus and child. The Lancet.

Whiteford, G.(2000). Occupational deprivation: Global challenge in the new millennium. British Journal of Occupational Therapy.

World Health Organisation. (2016). Improving maternal and child health.

0 notes

Text

The Future of Occupational Therapy and My Journey to Prepare.

I’m a 3rd-year Occupational Therapy (OT) student at the University of KwaZulu-Natal (UKZN), and I’m passionate about the field. Over the past 12 weeks, I’ve had the opportunity to visit various clinical sites and put the theory I’ve learned into practice. It’s been an eye-opening experience, and I feel more connected to OT than ever before. As I look ahead to my final year and beyond, I’m excited about where the profession is heading and how I’m preparing for it.

Why Occupational Therapy Has a Bright Future?

Occupational Therapy is increasingly recognized as an essential part of healthcare. Historically known for physical rehabilitation, OT has expanded to include mental health, cognitive rehabilitation, and more. The future is promising because OT helps individuals live full and meaningful lives, whether they’re recovering from physical injuries or managing mental health conditions. According to the World Federation of Occupational Therapists (WFOT), OT plays a crucial role in promoting health, well-being, and independence across all ages.

Mental health is a growing focus within OT. As awareness of mental health issues increases globally, so does the recognition that OT has a unique role in this area. Through therapeutic activities and a client-centered approach, OT helps individuals develop coping skills, improve emotional regulation, and reintegrate into everyday life. This makes OT vital in the broader mental health field.

Technology is also revolutionizing OT practice. The use of telehealth, for example, is allowing occupational therapists to reach clients in remote areas. Research shows that telehealth has been effective in providing OT services for individuals who have limited access to traditional in-person care, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic. Assistive technologies, such as adaptive devices, are helping clients achieve greater independence, another key trend driving the future of OT.

How I’m Preparing for This Future.

During my 12 weeks of practical experience, I’ve worked with a variety of clients, including those with intellectual disabilities and mental health conditions like schizophrenia and Bipolar Mood disorder. These experiences have not only helped me develop clinical skills but also taught me how to be adaptable and empathetic in diverse situations. As OT moves toward a more holistic and individualized approach, these skills will be crucial.

I’m also learning to apply different models of care. The Person-Environment-Occupation-Performance (PEO-P) model has been particularly useful in understanding the complex interactions between individuals, their environments, and their daily activities. By considering these factors together, I can better plan interventions that are both client-centered and goal-oriented.

Cultural sensitivity is another area I’m focused on. In South Africa, many people hold traditional beliefs that influence how they view health and healing. Learning how to respect and integrate these beliefs into OT practice will be essential as the profession continues to expand into more diverse and multicultural settings. Cultural competence has been shown to improve therapeutic outcomes and build trust with clients.

Next year is my final year of the 4-year OT degree, and I’m excited to continue building on what I’ve learned. I’ll take on more responsibilities in my clinical placements, further refining my skills as I prepare to enter the workforce. Whether I end up working in mental health, paediatrics, or community-based settings, I’m committed to making a meaningful impact in people’s lives.

The future of OT is full of possibilities, and I’m ready to be part of it. With a combination of hands-on experience, theoretical knowledge, and a passion for helping others, I believe I’m well-prepared to face the challenges and opportunities ahead.

REFERENCES.

Davis, R., & Smith, L. (2019). Cultural competence in occupational therapy: A guide for practitioners. OT Practice, 24(5), 24-30.

Hayes, L., & Lannin, N. (2020). The role of OT in mental health recovery. Journal of Mental Health Therapy, 15(3), 45-57.

Law, M., Cooper, B., Strong, S., Stewart, D., Rigby, P., & Letts, L. (1996). The person-environment-occupation model: A transactive approach to occupational performance. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 63(1), 9-23. https://doi.org/10.1177/000841749606300103

O’Brien, J., & Hussey, S. (2022). Telehealth in occupational therapy: Access and outcomes in remote areas. OT International, 8(2), 101-115.

World Federation of Occupational Therapists. (2021). Promoting the profession of occupational therapy worldwide. World Federation of Occupational Therapists. https://www.wfot.org

0 notes

Text

My Reflection on The King of Staten Island Movie.

The King of Staten Island tells the story of Scott, a 24-year-old man drifting through life with little sense of purpose. Living with his mother and stuck in the emotional aftermath of losing his firefighter father at a young age, Scott struggles with unresolved trauma, mental health challenges, and a lack of direction. His days are filled with hanging out with friends, smoking weed, and half-heartedly pursuing his dream of becoming a tattoo artist, but he remains trapped in a cycle of grief and stagnation. These issues deeply affect his participation in meaningful areas of occupation.

Scott’s unresolved grief and trauma are central to his inability to move forward. The death of his father left a lasting impact, and he is particularly resistant to his mother forming a new relationship, especially with another firefighter (out of fear that they too might die). This fear, though understandable, causes conflict within the family. Scott’s avoidance of personal growth, lack of motivation to seek employment, and reliance on humor and isolation as coping strategies highlight the psychological impact of his trauma. This taught me that trauma can lead to aggression, impulsivity, and emotional withdrawal, which negatively affect interpersonal relationships, role fulfillment, and the ability to form new, healthy connections. Scott’s behavior is an example of occupational alienation, where an individual feels disconnected from meaningful activities and roles in their life.

Throughout the film, Scott also exhibits symptoms of depression. His low self-esteem and belief that he is not good enough to succeed prevent him from pursuing meaningful goals, like improving his tattooing skills. He lacks energy, motivation, and purpose, often spending his days in boredom. Signs of this depression include disturbed sleeping patterns, frequent periods of sleep late and difficulty structuring his days, and substance abuse. Scott regularly smokes weed to escape his emotional pain and boredom, using it as a coping mechanism to numb his feelings. This taught me that depression can create an occupational imbalance, where an individual’s habits and routines are dominated by maladaptive behaviors, further deepening feelings of disconnection and despair (Townsend & Polatajko, 2007).

Scott’s anxiety also plays a major role in his inability to move forward. He constantly worries about his family’s safety, fearing that he is the only one left to protect them. Despite having friends, he struggles with forming deeper connections and often withdraws emotionally, displaying signs of social anxiety. In social gatherings, he tends to sit alone, smoke, and avoid engaging with others. His sarcastic humor and impulsive actions, like tattooing people without their consent, are ways he masks his anxiety. This highlighted for me how anxiety can prevent someone from building and maintaining relationships, reinforcing isolation and occupational deprivation (Townsend & Polatajko, 2007).

One of the most striking aspects of Scott’s character is his pattern of self-sabotage. Though he has growth potential, he repeatedly undermines himself through reckless behavior and an unwillingness to directly address his mental health issues. His relationships, especially with his mother and girlfriend, suffer as a result, as he struggles to control his emotions and maintain stable connections. His dream of becoming a tattoo artist remains unfulfilled because he lacks the motivation and commitment to improve his skills and pursue opportunities. This demonstrates how unresolved trauma, anxiety, and depression can disrupt volition (the motivation to act) leading to stagnation in life (Wilcock & Hocking, 2015).

By the end of the film, Scott begins to confront his unresolved grief and trauma. With the support of his family, he starts to focus on his career and his relationships, showing that healing and personal growth are possible with the right support systems in place. This transformation underscored the importance of expressing emotions and having a strong social support network in recovery.

Reflections as an OT Student

As an OT student, The King of Staten Island taught me several valuable lessons that I can apply to my practice. First, the importance of self-expression in managing emotional tension became clear to me. Encouraging clients to express their feelings can reduce stress and promote mental clarity. Second, the film demonstrated how crucial it is to have a supportive environment when addressing mental health challenges. Family and friends play a vital role in providing the encouragement needed for healing.

The film also emphasized the need for a structured daily routine, which is essential for maintaining balance in life. For someone like Scott, who struggles with motivation, implementing a structured routine can guide daily activities, reduce overwhelm, and alleviate anxiety. Additionally, the importance of strong social and interpersonal skills was evident, as Scott’s difficulties in maintaining relationships further contributed to his isolation. Helping clients develop these skills is critical for fostering healthy, supportive relationships.

Another key takeaway was the importance of vocational skills in achieving independence. Scott’s dream of becoming a tattoo artist was hindered by his lack of motivation and practical skills. As an OT, I see the value in helping clients acquire the necessary vocational and life skills to achieve their goals and lead more fulfilling lives. Lastly, the film underscored the importance of independence in instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs), as Scott remained highly dependent on his mother for support. Encouraging clients to gain independence in all areas of life is a core objective of occupational therapy

Conclusion

The King of Staten Island offers a profound exploration of grief, trauma, and mental health, illustrating how these challenges can impact everyday life and participation in meaningful occupations. Scott’s journey reminds me of the crucial role that occupational therapy can play in helping individuals develop the coping skills, routines, and support systems necessary for personal growth and recovery. This film has deepened my understanding of how mental health issues affect occupational performance and reinforced the importance of holistic, client-centered care in my future practice.

REFERENCES

Christiansen, C. H., & Townsend, E. A. (2010). Introduction to occupation: The art and science of living. Prentice Hall.

Kielhofner, G. (2008). Model of human occupation: Theory and application. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Rebeiro, K. L. (2001). Occupational choice, occupational change, and occupational alienation: A longitudinal study of work transitions in the lives of women with children. Journal of Occupational Science, 8(2), 44-53.

Townsend, E., & Polatajko, H. (2007). Enabling occupation II: Advancing an occupational therapy vision for health, well-being, and justice through occupation. CAOT Publications ACE.

Wilcock, A. A., & Hocking, C. (2015). An occupational perspective of health (3rd ed.). Slack Incorporated.

0 notes

Text

SOCIAL MEDIA: THE OPPRESSOR THE TOUTH'S MENTAL HEALTH.

In today’s world, social media is everywhere, offering a way to connect and share. But while it seems like a fun place for young people, it’s also quietly harming their mental health. Beneath the surface of likes and comments, many young people struggle with anxiety, depression, and low self-esteem, constantly comparing themselves to unrealistic images of others. What was meant to bring people together is now causing harm, making young people question their self-worth. The question is no longer if, but how deeply it affects their mental health.

According to Erikson’s psychosocial stages of development, the youth is in the “identity vs confusion” developmental stage (Erikson, 1968). In this stage, individuals are emotionally sensitive to peoples’ comments about themselves which tends to elicit feelings of inadequacy, thus negatively affecting their self-esteem and self-efficacy (Erikson,1968). They have the urge to be accepted and be like every other person, including having the same types of clothing brands, and technological gadgets, and traveling to mostly visited places. They may engage in behaviours of substance use, such as alcohol and cannabis as seen in social media. However, when they cannot control the fear of missing out (FOMO), they likely develop mental health issues over time (Johnson et al.,2022).

In our South African economic inequality, social media exposes the youth to these facts and makes them realize that their lives are not enough, thus resulting in the development of depression, frustration, and anxiety. For example, young people from low socioeconomic backgrounds tend to want what peers from high socioeconomic backgrounds showcase on their social media platforms and this creates pressure since they cannot afford to have what they see, causes depression and self-loathing (Smith,2022). Studies indicate that nearly 1 in 4 young people experience symptoms of depression, making it a widespread concern (Van der Westhuizen et al., 2018).

Social media particularly Instagram, has manipulated the minds of the youth in that it has developed the ideal “body or appearance” of how a man or woman should look and this has negatively impacted the body image of young people often leading to body dysphoric disorders (dissatisfied with body features/ashamed of their body). The youth from high socioeconomic backgrounds do plastic surgery to be like famous celebrities on social media. The pressure to “fit in” increases insecurities, contributing to decreased self-esteem, poor body image, and low self-confidence (Smith et al.,2022).

According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), depression is globally the third highest disease burden among adolescents, and suicide the second leading cause of death in 15- to 29-year-olds (World Health Organisation, 2021), while the South African Depression and Anxiety Group (SADAG) states that 9% of teenage deaths in the country are due to suicide (SADAG, 2022). Cyberbullying is one of the most contributing factors to suicide amongst the youth as result of criticism that comes from people’s comments and likes on social platforms. The youth fail to understand that a “like” is nothing but a reaction and a comment by a stranger may not reflect true feelings and intentions (Smith et al.,2022).

This is further supported by an article titled, “What Doctors Wish Patients Knew About Social Media’s Toxic Impact” by Sara Berg. It accentuates the impact of how comparison in social media affects the lives of the youth, which leads to body image issues, body dysmorphia, and comparisons of success in life (Berg, 2023). It explains how social media makes everyone’s life look fabulous and fantastic and omits all their struggles and shortcomings. This unrealist portrays puts pressure on the youth be perfect and not make mistakes, which is impossible realistically since humans are no infallible. When they fail to meet these standards they resort to feelings of inadequacy, depression, and anxiety (Berg, 2023). The article emphasizes the need for awareness and mindful use of these platforms to mitigate the negative mental health effects.

Occupational therapists play a key role in assisting the youth with these mental health problems by engaging them in group therapy that will focus on building their self-awareness by teaching them coping strategies to manage anxiety and depressive symptoms triggered by social media (Smith & Jones, 2020). Role-playing and social skills training will focus on building confidence to reinforce social participation, helping them engage more positively with others (Brown,2019). Additionally, helping to develop healthy routines to live and lead a balanced lifestyle and encouraging offline engagement to help them find joy beyond social media platforms (Johnson & Lee, 2021). Educating the family about social media's impact will create a supportive environment at home (Davis &White, 2020).

In conclusion, knowing who you are, what you want, and where you come from can protect you from the pressures and unrealistic standards seen on social media. Building self-awareness helps you handle social media better and resist peer pressure. Working with occupational therapists and psychologists can support you in managing your social media use and staying true to yourself. With this help, you can stay confident and focused on what really matters.

REFERENCES

Berg, S. (2023). What doctors wish patients knew about social media’s toxic impact. AMA Journal. https://www.ama-assn.org/

Brown, C., & Smith, J. (2021). Social media influences on adolescent identity and self-esteem. Journal of Adolescent Health, 67(2), 123-130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.03.011

Erikson, E. H. (1968). Identity: Youth and crisis. W. W. Norton & Company.

Johnson, D., Lee, M., & White, K. (2022). The effects of FOMO on adolescent mental health. Journal of Youth Psychology, 12(1), 45-58. https://doi.org/10.1007/jyp.2022.013

Smith, J. (2022). The role of social media in exacerbating socioeconomic disparities among youth. Journal of Social Media Studies, 10(3), 150-165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socmed.2022.007

Smith, J., Brown, T., & Lee, K. (2022). The impact of social media on body image and mental health among youth. Journal of Youth Mental Health, 18(4), 200-212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jymh.2022.004

Smith, J., Brown, T., & Lee, K. (2022). The impact of social media on mental health and suicide risk among youth. Journal of Youth Mental Health, 18(2), 95-107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jymh.2022.002

South African Depression and Anxiety Group (SADAG). (2022). Youth suicide statistics in South Africa. SADAG Report. https://www.sadag.org/

Van der Westhuizen, C., Smith, J., & Brown, T. (2018). Economic inequality and mental health: The impact on South African youth. South African Journal of Psychiatry, 24(1), 453-461. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajpsy.v24i1.453

World Health Organization. (2021). Mental health and substance use: Adolescent health. WHO. https://www.who.int/teams/mental-health-and-substance-use/adolescent-health

World Health Organization. (2021). Suicide: A global health crisis. WHO Mental Health Division. https://www.who.int/

0 notes

Text

HOW SOCIAL SUPPORT BOOSTS MENTAL HEALTH AND WELLNESS

Think of social support like a safety net that catches you when you fall. When you face challenges or feel down, having friends, family or a supportive community can make a big difference. They offer encouragement, help, and a sense of belonging, which help you feel stronger and more balanced. Am a 3rd-year Occupational therapy student and am going to discuss the role of social support, connecting it to how it can boost or help the mental health and well-being of people with mental disabilities.

People are social beings and having relationships with other people is part of our human nature. Having good relationships with people can help develop positive attitudes and behaviour. These can assist with reducing stress levels (Cohen &Wills, 1985), enhance resilience (Taylor,2011), better physical health (Uchino, 2006) and increase life satisfaction in that one can have a sense of purpose and feel valued by others. For example, I have noticed that patients who have good relationships with hospital staff and their families are always happy and are seldom found sad or angry, this is because there’s always someone there to comfort them in their time of need.

However, in patients with cognitive disabilities like schizophrenia, personality disorders, or bipolar disorder, it is a different story in that they may have delusions or hallucinations that might hinder the establishment of these relationships because of beliefs that they were bewitched or someone used dark magic on them, or they are sent by GOD to save people and that’s where Occupational therapy comes in to rebuild that support.

A patient that has dementia may have problems with memory and this will affect his/her social relationships because she might have a poor orientation to reality and not recognize her surroundings, her relatives, or friends who have come to give her support. Occupational therapy can intervene by helping the clients restore memory by engaging in reminiscence group therapy sessions or reality orientation programs.

Occupational therapists can help the patients by engaging in group therapy which could teach about proper social behaviour and social skills which are building blocks of social support and maintaining relationships through role-playing as it was done in one of our group therapy sessions at Pixley Hospital. This was very helpful but, requires repetitions to reinforce the behaviour. Occupational therapists can adjust the living environment to support social interactions such as making space accessible and welcoming visitors (Cohen et al.,2014) and doing family education sessions by educating family members on effective communication and interaction strategies they can use with the client (Tremont et al,.2006).

They can also encourage the clients to engage in activities such as volunteer work, hobby groups or other meaningful activities that help build social connections (Hammel et al., 2008), for example: In the Sherwood training workshop Challenge the clients to work together when making earplugs thus developing social support through socialization.

In looking at the impact of social support on mental health, it’s clear to me that the connections are vital. Occupational therapy plays a big role in enhancing social support for mental health care, affirming that well-being is profoundly interconnected with the strength and quality of our social relationships and I highly encourage patients to build good relationships with families and friends so keep their mental health as fit as a fiddle.

REFERENCES

Cohen, S., & Wills, T. A. (1985). Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin, 98(2), 310–357. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.98.2.310

Taylor, S. E. (2011). Social support: A review. In M. S. Friedman (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of health psychology (pp. 189–214). Oxford University Press.

Uchino, B. N. (2006). Social support and health: A review of physiological processes potentially underlying links to disease outcomes. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 29(4), 377-387. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-006-9056-5

Tremont, G., Davis, J. D., & Bishop, D. S. (2006). The unique contribution of family functioning in caregivers of patients with mild to moderate dementia. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders, 21(3), 170-174. https://doi.org/10.1159/000090631

Hammel, J., Magasi, S., Heinemann, A., Whiteneck, G., Bogner, J., & Rodriguez, E. (2008). What does participation mean? An insider perspective from people with disabilities. Disability and Rehabilitation, 30(19), 1445-1460. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638280701625534

0 notes

Text

HOW SOCIAL SUPPORT BOOSTS MENTAL HEALTH AND WELL.

Think of social support like a safety net that catches you when you fall. When you face challenges or feel down, having friends, family or a supportive community can make a big difference. They offer encouragement, help, and a sense of belonging, which help you feel stronger and more balanced. Am a 3rd-year Occupational therapy student and am going to discuss the role of social support, connecting it to how it can boost or help the mental health and well-being of people with mental disabilities.

A patient that has dementia may have problems with memory and this will affect his/her social relationships because she might have a poor orientation to reality and not recognize her surroundings, her relatives, or friends who have come to give her support. Occupational therapy can intervene by helping the clients restore memory by engaging in reminiscence group therapy sessions or reality orientation programs. Occupational therapists can help the patients by engaging in group therapy which could teach about proper social behaviour and social skills which are building blocks of social support and maintaining relationships through role-playing as it was done in one of our group therapy sessions at Pixley Hospital. This was very helpful but, requires repetitions to reinforce the behaviour. Occupational therapists can adjust the living environment to support social interactions such as making space accessible and welcoming visitors (Cohen et al.,2014) and doing family education sessions by educating family members on effective communication and interaction strategies they can use with the client (Tremont et al,.2006). They can also encourage the clients to engage in activities such as volunteer work, hobby groups or other meaningful activities that help build social connections (Hammel et al., 2008), for example: In the Sherwood training workshop Challenge the clients to work together when making earplugs thus developing social support through socialization.

In looking at the impact of social support on mental health, it’s clear to me that the connections are vital. Occupational therapy plays a big role in enhancing social support for mental health care, affirming that well-being is profoundly interconnected with the strength and quality of our social relationships and I highly encourage patients to build good relationships with families and friends so keep their mental health as fit as a fiddle.

REFERENCES

Cohen, S., & Wills, T. A. (1985). Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin, 98(2), 310–357. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.98.2.310

Taylor, S. E. (2011). Social support: A review. In M. S. Friedman (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of health psychology (pp. 189–214). Oxford University Press.

Uchino, B. N. (2006). Social support and health: A review of physiological processes potentially underlying links to disease outcomes. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 29(4), 377-387. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-006-9056-5

Tremont, G., Davis, J. D., & Bishop, D. S. (2006). The unique contribution of family functioning in caregivers of patients with mild to moderate dementia. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders, 21(3), 170-174. https://doi.org/10.1159/000090631

Hammel, J., Magasi, S., Heinemann, A., Whiteneck, G., Bogner, J., & Rodriguez, E. (2008). What does participation mean? An insider perspective from people with disabilities. Disability and Rehabilitation, 30(19), 1445-1460. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638280701625534

0 notes

Text

Healing Minds with Occupational Therapy in Mental Health

Occupational therapy is about more than just recovery; it is about reclaiming people’s lives to be filled with joy and meaning. In the realm of mental health, occupational therapists walk alongside individuals on their journey toward healing, offering guidance, support, and hope (American Occupational Therapy Association [AOTA], 2020). Focusing on the activities and routines that give life purpose, helps clients rebuild confidence, restore a sense of self, and find balance in life's challenges (Brown et al., 2017).

In my view, mental health is one of the less prioritized sectors by the Department of Health in South Africa. Yet, according to research, South Africa has a 12-month prevalence estimate of 16.5% for common mental disorders such as anxiety, mood, and substance use disorders, with almost a third (30.3%) of the population having experienced a common mental disorder in their lifetime (Herman et al., 2009).

Fortunately, occupational therapy can help people cope with these mental disorders by using various techniques listed below :

Cognitive Restructuring Techniques

This technique helps individuals notice, challenge, and change negative thinking patterns that can become limiting and self-defeating (Beck, 2011). It encourages people to change their negative thoughts into positive ones and to speak to someone about their feelings or write them down as a form of expression (Padesky & Mooney, 1990). For example, my client has feelings of inadequacy and feels like a failure thus I tried to manipulate her thinking by encouraging her to be grateful for what she has and focus on the positive side.

Problem-Solving Techniques

This technique gives patients the tools to identify problems and find ways to solve them. The steps include finding the problem, gathering facts, understanding the problem, thinking of ideas, picking the best idea, putting the idea to work, checking if it worked, and learning from it (Nezu et al., 2013).

Activity Exposure

Occupational therapists help patients build confidence by giving them a safe, controlled way to adjust to the environment and activity they need or want to return to. For example, by creating a social group where patients with schizophrenia practice social skills, such as greeting others, participating in group conversations, or attending a community event (Perlick et al., 2006). Additionally, they can be included in music and movement therapy groups to bring felicity and joy, which results in increased activity participation and eventually reconstructs their behaviour and thinking (Silverman, 2014).

Supportive Structure

Occupational therapists often help patients create daily routines and set specific goals that help them progress toward a desired lifestyle (Baum & Law, 1997). For example, for a client with schizophrenia, the first priority would be for the client to gain intellectual insight to ensure compliance with medication intake and therapy. The second aim would be to minimize hallucinations and delusions by teaching the client psychosocial strategies. The third aim would be to enable the client to be independent in all areas of occupation (Liberman et al., 2008).

Occupational therapy uses the above methods in their everyday practice in Mental health to strive for recovery of patients with mental health problems and I highly recommend it for current and future use.

REFERENCES

American Occupational Therapy Association. (2020). Occupational therapy practice framework: Domain and process (4th ed.). AOTA Press.

Baum, C., & Law, M. (1997). Occupational therapy practice: Focusing on occupational performance. Slack Incorporated.

Beck, A. T. (2011). Cognitive therapy: Basics and beyond. Guilford Press.

Brown, T., Stoffel, V. C., & Munoz, J. P. (2017). Occupational therapy in mental health: A vision for participation. F.A. Davis.

Herman, A. A., Stein, D. J., Seedat, S., Heeringa, S. G., Moomal, H., & Williams, D. R. (2009). The South African Stress and Health (SASH) study: 12-month and lifetime prevalence of common mental disorders. South African Medical Journal, 99(5), 339-344.

Liberman, R. P., Kopelowicz, A., Ventura, J., & Gutkind, D. (2002). Operational criteria and factors related to recovery from schizophrenia. International Review of Psychiatry, 14(4), 256-272.

Nezu, A. M., Nezu, C. M., & D'Zurilla, T. J. (2013). Problem-solving therapy: A treatment manual. Springer Publishing Company.

Padesky, C. A., & Mooney, K. A. (1990). Presenting the cognitive model to clients. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy, 3(2), 191-198.

Perlick, D. A., Rosenheck, R. A., Clarkin, J. F., Sirey, J. A., Salahi, J., Struening, E., & Link, B. G. (1996). Impact of family burden and patient symptom status on the expression of anger in caregivers of patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatric Services, 47(1), 1-10.

Silverman, M. J. (2014). Effects of music therapy on change in coping skills in battered women. Journal of Family Violence, 18(1), 29-40.

0 notes

Text

MY REFLECTION ON WHAT I LEARN ABOUT CLIENT-CENTRED PRACTICE.

In the ever-changing healthcare landscape, one principle stands out: client-centred practice. It's more than a term or a fad; it's a concept that prioritizes the individual in care, putting their autonomy, preferences, and special needs at the forefront of every decision and contact. Consider a healthcare experience in which individuals are active participants in their health journeys rather than passive care recipients. This is the essence of client-centred practice: a groundbreaking method that not only fosters trust and collaboration but also lays the framework for truly transformative and empowering healthcare experiences. In this blog, I will share my experience about how I’ve been implementing client-centred practice in my therapy intervention with clients in Mshiyeni Memorial Hospital.

I currently have an 18-year-old patient with partial-thickness burns on his face and bilateral upper limbs, he worked in a carwash and lives alone in his 1 shanty room. We have been working together for 3 weeks now. “Client-centred practice emphasizes the importance of understanding the patient's perspective and tailoring care to meet their unique needs and preferences” (Annals of Family Medicine, vol. 9, no. 2, 2011, pp. 100–103.), thus on the 1st day I saw him, we set up goals that we would like to achieve whilst in the hospital while considering his interest, concerns, and preferences. “Client-centred practice empowers patients to actively participate in decision-making regarding their health, fostering a sense of ownership and accountability” New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 366, no. 9, 2012, pp. 780–781.), thus we set goals into priorities and set steps of how they will be achieved. “In client-centred practice, the focus shifts from 'What is the matter?' to 'What matters to you?” (Social Science & Medicine, vol. 51, no. 7, 2000, pp. 1087–1110.), one of the patient’s goals was to be able to use his ULs to feed himself without the help of nurses and we first did upper limb exercises to release joint stiffness (prevention of skin contractures) before we did a modified feeding activity. The activity was a bit challenging for the client as the bandages were tightly wrapped on the limbs and there was a lot of compensation. Therefore, I had to debulk the bandages on the hand to facilitate finger movement. It was a bit challenging at first because the client was recently admitted and in excruciating pain thus had to incorporate therapeutic use of self (empathizing mode) to calm him down and show compassion. I asked for his parent's numbers so that I could update them about our progress of intervention and include decision-making such as whether he should be discharged and why or why not. Now the client’s occupational performance has improved and we’ve achieved 50% of our goals so far and that is motivating for me.

The second client I had was a 51-year-old female who presented with paraparesis and trunk pain. I first interviewed her so that I would know her background context. We set short and long-term goals with the patient while considering her interests and preferences. One of her first goals was to walk, but I explained to her that walking is a process and firstly she needs to learn how to roll on the bed and sit without falling as she has a poor static and dynamic sitting balance. Therefore, we did bed rolling (bed mobility training) and now she can take things from the side bed table. She was very happy to see such improvement because she used to call nurses every time, she needed something from the table. Secondly, we attempted our second goal of sitting at the edge of the bed, but the client set for a short time and complained about excruciating pain in the trunk. We tried this several times on different days, but it got worse daily, and this demotivated us because our goal seemed elusive. I advocated for the client to get bisacodyl to help relieve constipation as she hadn’t gone to the loo for 10 days. She was referred to Nkosi Albert Luthuli Hospital for further intervention, but I hope she will return soon so that we continue with achieving our goals.

Client-centredness is very important because it requires me to be flexible and change according to the client’s needs. I’ve learned to approach and treat people differently because they are different and have different occupational profiles as mentioned above with two patient scenarios. Even if people present with the same diagnosis their goals are never the same and that is why I highly recommend the use of this practice in the future and by other healthcare practitioners.

As I conclude I could say that by centering care around what truly matters to each individual, we not only enhance clinical outcomes but also nurture a profound sense of connection and humanity within the healthcare experience thus we should continue using this practice in everyday lives of our patients in the healthcare system.

REFERENCES.

Bechtold, A., & Fredericks, S. (2021). Key concepts in providing patient-centered care. INDIGO (University of Illinois at Chicago). https://doi.org/10.32920/ryerson.14636718.v1

Coffey, M. J. (2017). Patient-centered communication during procedures. The American Journal of Surgery, 213(6), 1188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2016.08.004

Papalois, V. E., & Theodosopoulou, M. (2018). Optimizing health literacy for improved clinical practices. Medical Information Science Reference.

Platt, F. W., Gaspar, D. L., Coulehan, J. L., Fox, L., Adler, A. J., Weston, W. W., Smith, R. C., & Stewart, M. (2001). “Tell Me about Yourself”: The Patient-Centered Interview. Annals of Internal Medicine, 134(11), 1079. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-134-11-200106050-00020

Rathert, C., Wyrwich, M. D., & Boren, S. A. (2013). Patient-Centered Care and Outcomes. Medical Care Research and Review, 70(4), 351–379. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077558712465774

0 notes

Text

My reflection on my experience of Advocating for patients.

Patients typically find themselves navigating a maze of procedures, diagnoses, and treatments in today's complex network of healthcare, their voices sometimes drowned out by the complexities. Advocating for patients in this system is like being a guiding light in the fog, illuminating pathways, amplifying voices, and ensuring that, despite the language and protocols, the human element is never forgotten. It is about advocating for people's rights, dignity, and well-being and empowering them to actively engage in healthcare decisions. Patient advocates play an important role in establishing a healthcare environment that welcomes everyone’s journey with empathy, understanding, and support, from ensuring access to quality care to campaigning for equal treatment. In this blog Am going to share my experience in advocating for my clients in Prince Mshiyeni Memorial Hospital.

Being a healthcare clinician means that you are the mouth and eyes of every patient in the hospital. In my clinical practical so far, I’ve realised the importance of seeking to help from other healthcare teams to intervene in the clients’ health to improve functional or medical outcomes. One of my patients had a spinal cord injury, was paraplegic, and was in the rehabilitative phase of treatment. He was referred to OT from physiotherapy for rehabilitation to ADLS and IADLS. The patient had a good functional and medical prognosis, but the rehabilitation wasn’t adequate without the wheelchair thus I had to advocate for a wheelchair so that he would be able to mobilize independently. However, the client was discharged without the wheelchair due to a delay in ordering and the tight budget that the hospital has for wheelchairs. I couldn’t believe it, but when I made a follow-up, the physio said that they would call him when the wheelchair arrived and that would be after 8 weeks. Advocating for clients can be difficult sometimes because the request on behalf of the client can take a long time to be fulfilled and sometimes it’s not considered which could be due to a broken Multidisciplinary team in the healthcare system.

I’ve learned that not everything that my patient requests should be advocated because I know what is best for my client to become functionally independent. One of my recent clients has paraparesis and presents with poor static sitting balance as one of the impaired client factors therefore I advocated and asked the nurses in the ward to not feed her as she can do it independently and should be allowed to sit. However, this was not considered because when I came to the ward again, I found her being fed by the nurse while lying supine. This demoralized me and I felt like the nurses were not taking me seriously because am just a student OT, but I overcame that with the help of my supervisor and pushed the client into sitting at the edge of the bed to eat. This led me to think that being a healthcare student sometimes it’s hard to advocate because the hospital staff takes us lightly, however, this motivates me to do what is best for my clients irrespective of what they may think.

TYPES OF PATIENT ADVOCACY.

Medical advocacy

This includes making the client understand their diagnosis by translating medical conditions to them and their families.

I explained to the burn’s patient about the importance of the drinking the nutrient juice offered by a dietician to heal the skin.

Medical facility advocacy

Includes nurses and social workers who act as mediators between patients and physicians. They ensure that patients have safe accommodation etc.

I advocated for the paraparesis patient that she should be always put in sitting when eating to facilitate the development of trunk muscles to improve static sitting balance.

Health insurance advocacy

This includes assisting patients with benefits such as medical prescription, vision, Medicare/Medicaid, Veterans Affairs, social security, and home health.

Family Advocacy

This includes mediating conflicts between patients and their family members regarding medical treatment decisions.

Legal Advocacy

It includes helping individuals claim disability grants, work compensation or malpractice, and medical arrow review.

Transitions and Housing Placement advocacy

They aid in shifting to assisted living facilities, nursing homes, skilled nursing facilities, and adult family homes.

I advocated for the SCI patient’s family to change their home setting so that the patient would still have access to different areas of the house. This included putting rails in the toilet, building a ramp, and putting his most important daily use items lower to facilitate reaching.

Mental and behavioural health and social work advocacy

Mental and behavioural health and social work advocates assist patients in managing severe health conditions, addiction disorders, and communication difficulties caused by mental or behavioural obstacles. They can also consult with patients on relevant drugs and therapy.

I advocated for the burns patient by referring him to a psychiatrist after a reported psychic behaviour in the ward. It was found that he had a history of delirium but is currently psychotic.

Pain management Advocacy

This includes ensuring that pain is managed properly by recommending a change in the dosage or type of medication.

I advocated for my paraplegic patient who had pain in the stomach due to constipation by asking the doctor to provide the client with bisacodyl.

As I conclude and linking back to the aim of the introduction, I would say I've learned a lot about the importance of advocacy for clients and I wish to get more exposure to different conditions in the future so that I can develop advocacy skills that will link to different clients. I highly recommend it in the healthcare system or Multidisciplinary Team.

REFERENCES

References Dhillon, S. K., Wilkins, S., Law, M. C., Stewart, D. A., & Tremblay, M. (2010). Advocacy in Occupational Therapy: Exploring Clinicians’ Reasons and Experiences of Advocacy. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 77(4), 241–248. https://doi.org/10.2182/cjot.2010.77.4.6

Dhillon, S., Wilkins, S., Stewart, D., & Law, M. (2015). Understanding advocacy in action: A qualitative study. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 79(6), 345–352. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308022615583305

Types of Patient Advocacy. (n.d.). Www.painscale.com. https://www.painscale.com/article/types-of-patient-advocacy

0 notes

Text

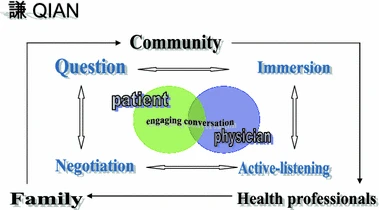

My Reflection on Collaborative Practice within the Multidisciplinary Team (MDT).

In the hectic hallways of healthcare, where urgency frequently trumps everything else, there is a symphony of expertise, a convergence of minds from several fields, each note harmonizing towards a single goal: healing. Welcome to the world of collaborative practice in healthcare, where the boundaries of expertise blur and the unity of purpose transcends separate areas. This blog will reflect on my experience in collaborative practice within the MDT in Prince Mshiyeni Hospital in Mlazi.

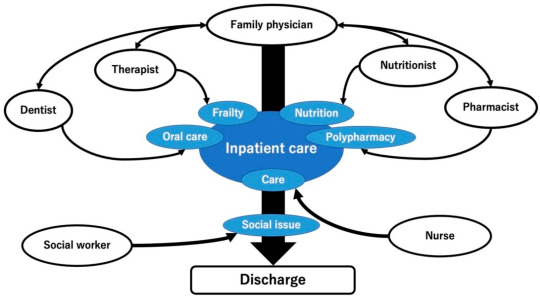

Doing clinical practices in a very busy hospital with numerous patients coming in and out has taught me the importance of having a multidisciplinary team. A multidisciplinary team (MDT) is a group of health and care staff who are members of different organizations and professions (e.g. GPs, social workers, nurses), that work together to make decisions regarding the treatment of individual patients and service users(Benagiano, G., & Brosens,). As an OT student, I work with all healthcare professionals to gather information about the client to enable me to do assessment and intervention planning, and that led me to know the Multidisciplinary team diagram below:

I’ve learned that the multidisciplinary team members each have a role to play in the patient’s treatment and that is why referring the patient to a suitable healthcare specialist is beneficial (similar to advocating). For example, one of the patients that I see has T11-T10 complete SCI (paraplegic) and was referred to OT by physio for further rehab to activities of daily living, however it’s been two days of rehab with OT, and the client presented with pricking pain on the left chest and heavily breathes after that activity (dressing LL) which could be due to low physical endurance, therefore, I acknowledged nurse staff about this problem so that they would intervene by increasing pain medication dosage intake or refer to the doctor to analyze the patient’s chest X-ray. Their feedback will help with adapting the focus of my intervention to meet the patient’s functional level. It was a bit of a struggle initially ( first 3 days of practical) to adapt to the MDT at the hospital because I was hesitant to ask for help from the team around e.g. I was hesitant to ask for nurses to change the client’s catheter beg or ask the doctors what medication is the client taking and what are they for. However, all of that gradually deflated like a car tire that has a big hole, but now you wouldn’t even recognize that am a student (communication-wise) when am within the team in the patient wards. Many of the MDT members in the hospital have more experience than me and this means their professional language is way more mature, thus this posed a challenge to me when they asked me questions that required deep professional/clinical reasoning that I have not developed as yet but currently building, so this slightly diminished my self-esteem but motivated me at the same time. One of the things that I disliked about working within the team was how it seemed like they prioritized other health professionals over others as if they depended on them. This breaks the aim and purpose of the MDT and this leads to poor outcomes.

Below are multidisciplinary Team Benefits

Improved patient outcomes :Working with a multidisciplinary team allows you to treat the entire patient and provide comprehensive care. With each physician focused on a different aspect of the patient’s health, providers are more likely to identify areas of need, and subsequently manage those needs in an effective way

Streamlined workflows and time saved :Multidisciplinary care increases productivity and saves time within your healthcare organization. Trying to provide care across a healthcare system without coordination can lead to communication and care errors, i.e. time wasted. Working in a care team has shown to decrease service duplication, as tasks are communicated clearly and delegated to members to avoid such events