age 32, female, Canadian, bi with a bf. part-time potion maker (juices and smoothies and coffee) + artist who never finishes anything...

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

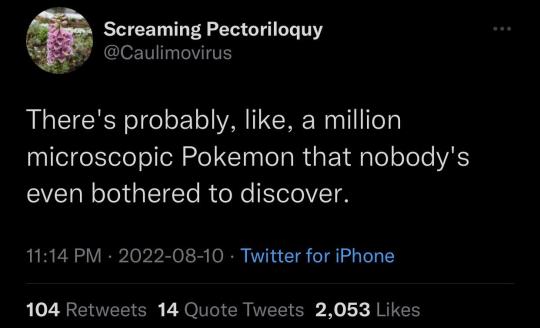

Text

It's been years since I started seeing nutrient flows constantly in my daily life, and the more I study agriculture, the more I see them.

See, every time you harvest something, you take the nutrients in that item away from the soil, and they go somewhere else. When I put a banana peel in my compost bin, I think (a little gleefully) about how I've just added an exotic, different profile of nutrients to my own property--but I also think about that distant banana plantation that lost tons of nutrients per year to US grocery stores, and I wonder what they replaced those nutrients with.

The farmer across my field grows corn, which gets harvested for feed. Corn is a nitrogen-hungry crop. Every year, that corn sucks up nutrients, which get harvested and shipped away. The farmer, being a conventional farmer, mostly replaces those with a conventional fertilizer. Nitrogen is often applied to fields in the form of ammonia fertilizer, which is made via a process that binds nitrogen in the air with hydrogen from natural gas. This feels like a vast resource, but of course we know it's not inexhaustible and not without cost.

Ideally, said farmer does soil tests and applies a carefully considered amount of ammonia. It is taken up by the growing plants and relatively little is lost. Possibly (often), though, some of the ammonia is leached out via rain and ends up in waterways, where it causes plant overgrowth and algal blooms, which harm the waterways in several ways, and turn those nutrients from a resource into a contaminant.

Meanwhile, the corn is also uptaking a variety of other nutrients from the soil which the commercial fertilizer is NOT replacing. Year by year, those nutrients get shipped off to distant feedlots and depleted in the soil. Eventually, those nutrients are gone from my neighbor's field and, quite possibly, languishing in a manure lagoon somewhere in, say, Indiana, where one can only hope it's properly treated and made into compost. But, you know. Not necessarily.

When I buy compost at the store, it's usually based in either cow manure or "forest products". Hopefully, depending on brand, those forest products MIGHT be collected municipal yard waste. Which is pretty good. Those suburbanites don't want their leaves, I do, win/win.

Except that because those suburbanites raked their yard waste, they now need at some point to fertilize their trees, shrubs, and turf grass. Meanwhile, they've eliminated habitat for the many insects that use leaf litter to either overwinter or reproduce. They may not be counting the costs, but the costs don't stop existing.

The ebb and flow of nutrients is something that, in the current system, goes utterly unregarded by most of the people taking part in the process. Even gardeners bring nutrients onto their soils mostly without thinking about the places those nutrients came from. I think in a sustainable world, that needs to change.

Also probably we need to do a hell of a lot more cover-cropping.

6K notes

·

View notes

Text

living in paris means u walk into a clothing store and there is a fucking thing. Name of GuGu.

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

The laws that govern the hydraulics are always interesting ..

19K notes

·

View notes

Photo

The marine eels and other members of the superorder Elopomorpha have a leptocephalus larval stage, which are flat and transparent. This group is quite diverse, containing 801 species in 24 orders, 24 families and 156 genera (super diverse).

Leptocephali have compressed bodies that contain jelly-like substances on the inside, with a thin layer of muscle with visible myomeres on the outside, a simple tube as a gut, dorsal and anal fins, but they lack pelvic fins. They also don’t have any red blood cells (most likely is respiration by passive diffusion), which they only begin produce when the change into the juvenile glass eel stage. Appears to feed on marine snow, tiny free-floating particles in the ocean.

This large size leptocephalus must be a species of Muraenidae (moray eels), and probably the larva of a long thin ribbon eel, which is metamorphosing, and is entering shallow water to finish metamorphosis into a young eel, in Bali, Indonesia.

Video: Filmed by Barry Haythorne and Rob Rutgers, HRF U/W Production

25K notes

·

View notes