Text

I want to write a book called “your character dies in the woods” that details all the pitfalls and dangers of being out on the road & in the wild for people without outdoors/wilderness experience bc I cannot keep reading narratives brush over life threatening conditions like nothing is happening.

I just read a book by one of my favorite authors whose plots are essentially airtight, but the MC was walking on a country road on a cold winter night and she was knocked down and fell into a drainage ditch covered in ice, broke through and got covered in icy mud and water.

Then she had a “miserable” 3 more miles to walk to the inn.

Babes she would not MAKE it to that inn.

142K notes

·

View notes

Text

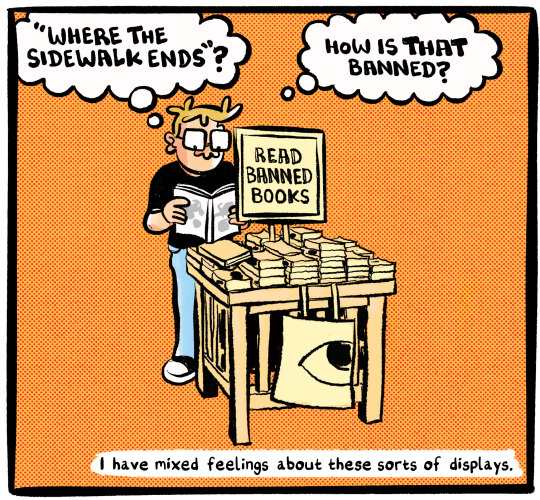

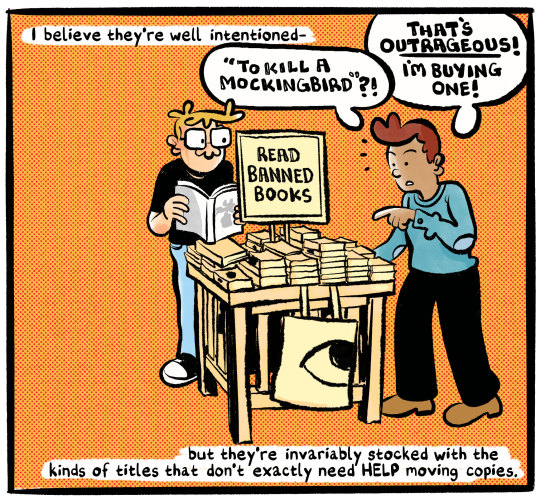

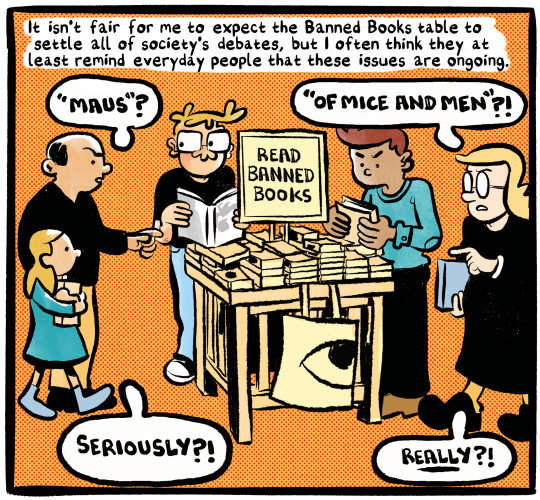

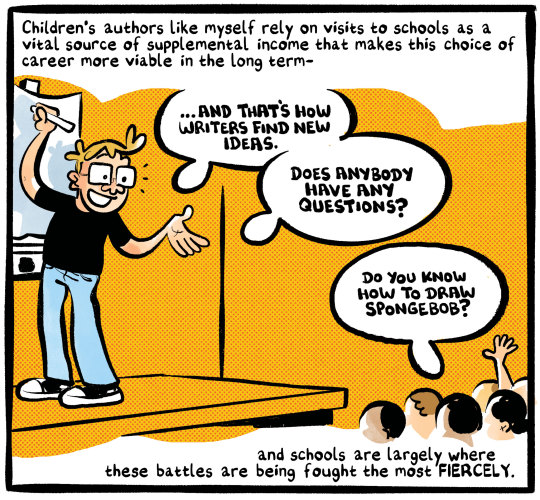

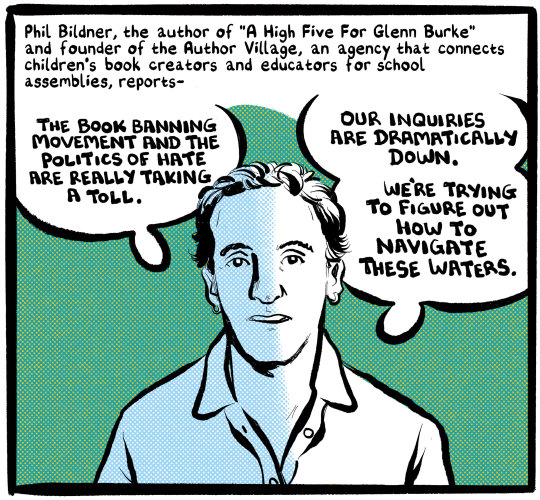

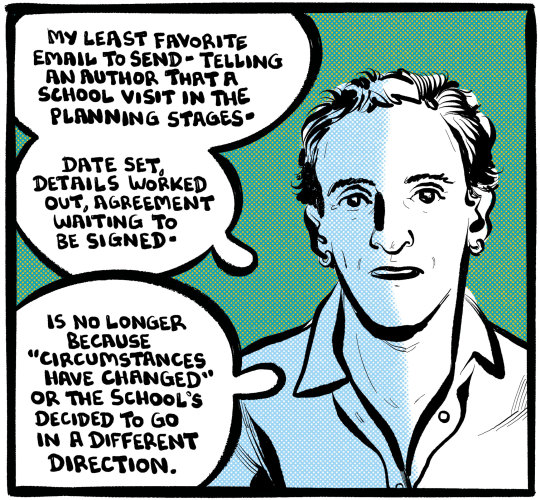

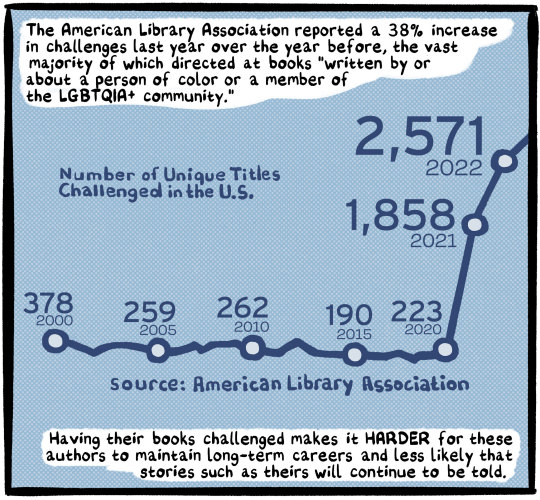

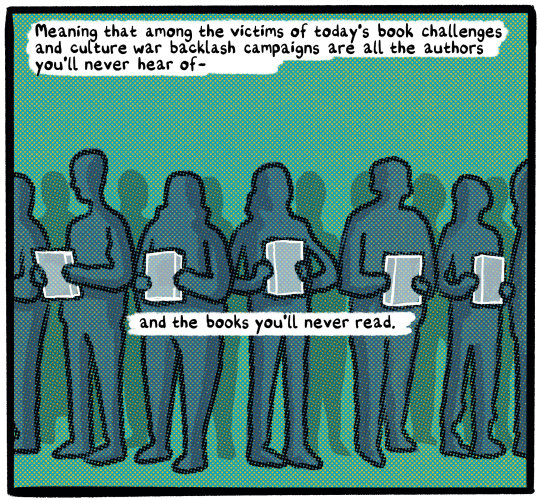

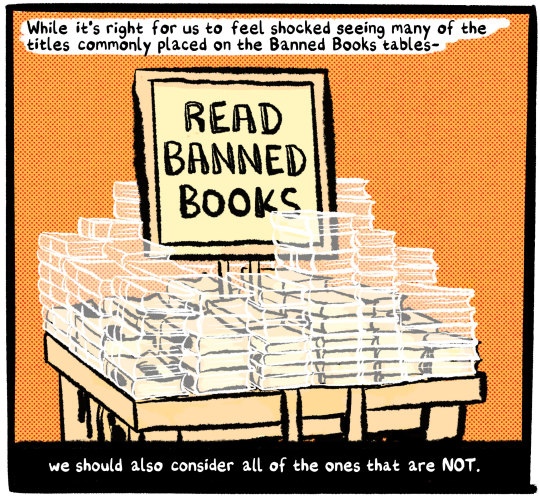

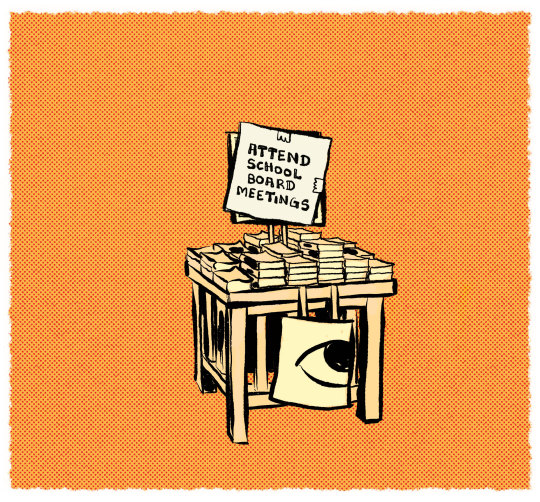

"Read Banned Books" a new full page cartoon essay published in The New York Times Arts & Leisure section today.

92K notes

·

View notes

Text

“I was prepared to be persuasive, touching, and hortatory, admonitory and expostulating, if need be vituperative even, indignant and sarcastic...”

The Moon and Sixpence, W. Somerset Maugham

I just really like this bit :)

The context is meaningful, but it doesn't feel as biting as some other Maugham that really hit me.

Oh and this, in the same lane:

“...with the martyred smile of sweet reasonableness that was his loyal confederate in every dispute...”

Catch-22, Joseph Heller

0 notes

Text

Sci-fi short stories are so efficient; they take 15 minutes to read and then you think about them for the next 5 years

75K notes

·

View notes

Text

The Path to the Spiders’ Nest (Preface)

“How easy it is, once one starts talking about literature, and even in the middle of the most serious, factual discussion, to slip unwittingly into telling stories... That is why literary analysis, whether my own or anyone else’s, annoys me more and more.”

The Path to the Spiders’ Nest, Italo Calvino (translated by Archibald Colquhoun)

This got a laugh out of me. My English teacher was the one that recommended practically all of Calvino to me. I think he’ll appreciate this though :D

“The beauty and difficulty of language is that you can never say exactly what you want to say: you always say both more and less.“

The Limits of My Language, Eva Meijer

I actually don’t have a lot to say right now. I’ve collected paragraphs I like, sentences worth remembering, and words that struck something in me, but at the moment I can’t really do anything about them except type them up and move the related ones next to each other. Trouble with literary analysis or language itself? Or not having strong enough of a feeling to need to write?

I had less than five pages of The Path to the Spiders’ Nest left when I was suddenly called away. Finished the book in a hurry and the ending didn’t leave me with much. Not sure if rushing through the last part diminished the book for me or.....

Well, let’s go back.

My first Calvino was If on a Winter’s Night a Traveler. And I absolutely loved it. The book may well have been “The Readers’ Manifesto” that I never knew I had been looking for and never knew I wanted. The preface to The Path to the Spiders’ Nest has a Calvino that I recognized form If on a Winter’s Night a Traveler: the beginnings and restarts, the roundabouts that never lose sight of where they started, the precision and descriptiveness in giving form to an abstract feeling or idea, and —

“What you read and what you experience in life are not two separate worlds, but one single cosmos. Every life-experience, in order to be interpreted properly, evokes certain things you have read and blends into them. That books always derive from other books is a truth which is only apparently in contradiction with the other truth, that books derive from practical existence and from our relations with other people.”

The Path to the Spiders’ Nest, Italo Calvino (translated by Archibald Colquhoun)

— the way these feelings and ideas resonate with me while expanding my limited experience.

“But when you are young every new book you read is like a new eye which opens on to the world and which modifies the viewpoint of the other eyes or book-eyes which you had before, and so in the midst of this new idea of literature which I longed to create, there was also space for a revival of all the literary worlds which had captivated me from childhood onwards...”

The Path to the Spiders’ Nest, Italo Calvino (translated by Archibald Colquhoun)

I picked up The Path to the Spiders’ Nest because it was Calvino’s first novel, and because the subject seems very different and more personal compared to his other works. I thought it would be a good place to get a better understanding of the author. With that in mind the preface to the book interested me more than the story did. If on a Winter’s Night a Traveler was written for readers. The preface to The Path to the Spiders’ Nest was written for writers.

“Perhaps, in the end, it is only your first book that counts, perhaps you should only write that one and stop; you only make the great leap that one time, the opportunity to express your real self happens only once, what you have to say inside you is either said at that point or never more. Perhaps real poetry is possible only at one moment in your life, which for most people coincides with their earliest youth. Once that phase has passed, whether you have expressed yourself or not (and you won’t know whether you have for a hundred, maybe a hundred and fifty years: contemporaries cannot be good judges), from that point on the die is cast, all you will do subsequently is imitate others or yourself, you won’t ever manage to produce a single word that is authentic or unique...”

The Path to the Spiders’ Nest, Italo Calvino (translated by Archibald Colquhoun)

I can’t say I really understand. I’ve been writing since second grade and only ever produced like two complete stories and they were both assignments. I begin something, get bogged down (this isn’t my magnum opus this isn’t my magnum opus this isn’t — oh my goodness what is this abomination did it really come from my hand) and never finish. Sometimes words build up and need to come out. So far I’ve found poetry to be the most successful outlet. I’ll take the above rumination as a forewarning for now.

I actually found that the preface resonated with me more than the story itself, perhaps not in the parts about writing, but here:

“My own story was that of someone whose adolescence had gone on too long, a young man who had seized on the war as an alibi, both in the literal sense of going somewhere else, and in its metaphorical sense. In the space of just as few years the alibi had become the here and now. It was too soon for me; or too late: I was too unprepared to live out the dreams I had dreamed for too long.”

The Path to the Spiders’ Nest, Italo Calvino (translated by Archibald Colquhoun)

Is it proper to call the novel a coming-of-age story? Pin stays the kid he is, and it’s better that he does. The book itself on the other hand was a coming-of-age project for Calvino. I read the story to get a look at WWII Italy. The preface became more of a look into myself. Once again Calvino gathers the thoughts and feelings I could never grasp and gives them shape. In the end I just wanted to keep this quotation.

Here’s one last thing I’m taking down. It’s not as important to me as the one above, but I’m thinking of going back to the Shakespeare parts in The Sandman with it to see if I can get a better interpretation of that story. Or save it for future reference.

“Memory, or rather experience — which is the memory of the event plus the wound it has inflicted on you, plus the change which it has wrought in you and which has made you different — experience is the basic nutrition also for a work of literature (but not only for that), the true source of wealth for every writer (but not only for the writer), and yet the minute it gives shape to a work of literature it withers and dies. The writer, after writing, finds that he is the poorest of men.”

The Path to the Spiders’ Nest, Italo Calvino (translated by Archibald Colquhoun)

Overall, this is what Calvino kept trying to get at in the preface.

0 notes

Text

Dune (Book 1)

“Anything outside yourself, this you can see and apply your logic to it. But it’s a human trait that when we encounter personal problems, those things most deeply personal are the most difficult to bring out for our logic to scan. We tend to flounder around, blaming everything but the actual, deep-seated thing that’s really chewing on us.”

Dune, Frank Herbert

I don’t have much energy left to write about Dune. I enjoyed it a lot. There are some great literary expressions that really makes one feel the setting, and absolutely fantastic characterization that embody “show don’t tell”. The events of Dune only takes place in a couple of weeks, and the ending is reveled from the very beginning. Somehow it’s still a very long book, somehow it still has suspense. It’s not like a lot of Russian short stories where I’m just waiting to see how the main character would come to a horrible end. I was there for the characters and the world. I didn’t care about the plot — that’s not to say the plot isn’t good, it’s a story of feud and deceit and betrayal filled with incredible nuance — but the book got me to care more about the who and what that things are happening to as opposed to just the happening. A lot of the story is told through inner monologue, which works so well here whereas in certain other works I might’ve cringed or gotten frustrated at the author for drawing things out and slowing the pace down (I love Timecrest but sometimes I really don’t want to read through the one-sided dialogues). Dune is a slow-paced book to begin with, and the displays of the inner workings of people tie well with the work’s themes of deception, capabilities of the mind, and humanity. It’s a Sherlock Holmes story in reverse, where the reader already knows the solution to the crime and is being told everything leading up to the ending by the big brain detective himself. It’s a spy story on a dissecting table, where the reader’s marvel towards the plan or the planners doesn’t result from a sudden revelation, but from every action and event throughout the story.

One thing I did find lacking in Dune though is a powerful emotional connection. I really don’t know if it’s just fiction’s magic fading for me, since I haven’t felt such a connection in a long time, or if it’s that I haven’t gotten to the end of Paul’s story.

“You know you've read a good book when you turn the last page and feel a little as if you have lost a friend.”

Paul Sweeney

I enjoyed every character I was introduced to (even the vile ones — I had hoped to see more of Piter, he makes a compelling villain and we don’t even know what his connection to Arrakis was or will be), but I didn’t really know any of them as I had know Aragorn, Frodo, the Little Prince, Arthur from The Once and Future King, Sara Crewe, Septimius Heap, and many others whose stories and person stayed with me even after their names had faded from my memory. Those are the characters that made me go on a reading hiatus as if I was mourning something. I know the characters in Dune as I know characters in my history book, just with much greater detail. I’m compelled by them, but not truly connected. I wonder if it’s because their standing is so different from mine — houses of royalty, people born to great power and responsibility. I was about to add “destiny” to the list but then realized plenty of main characters I did relate to have that “great destiny”. However, I was able to feel an emotional tug from 当年明月’s characterization of Zheng He and Zhu Di — the former, a personal tug; the latter, more of a lament for history — and that made me wonder if it’s because I’m getting to know the Dune characters too well, the way a psychiatrist would know a patient. In the end, I grew to love the world more than I do the people.

I said I didn’t have much energy left to write about Dune.....

At first I didn’t even want to quote anything from the book. Everything is written really well but they are also interconnected, so I can’t just take a piece out and have it make sense. But the quote at the very top hit me at a very stressful time, and it hit close to home. So did the one below:

“Do you wrestle with dreams? Do you contend with shadows? Do you move in a kind of sleep? Time has slipped away. Your life is stolen. You tarried with trifles, Victim of your folly.”

Dune, Frank Herbert

I actually wonder if I’m wasting time by writing this. I enjoy writing here. When I let my thoughts flow like this they also clash and form and spark new ideas. This is where I store my favorite sequence of words, where I keep track of my reading. But these are just trifling thoughts. The same reason I should stop is the same reason I don’t want to take English or Political Science as a major.

Anyhow, to leave off, a paragraph I couldn’t stop going back to read — it’s like the first time Darth Vader appears in Star Wars, or that time he displays force choking:

“A man in Harkonnen uniform skidded to a stop at the end of the hall, stared in at Yueh, taking in at a single glance Mapes’ body, the sprawled form of the Duke, Yueh standing there. The man held a lasgun in his right hand. There was a casual air of brutality about him, a sense of toughness and poise that sent a shiver through Yueh.”

Dune, Frank Herbert

0 notes

Text

Hávamál 139 & The Razor’s Edge

“I ween that I hung | on the windy tree, Hung there for nights full nine; With the spear I was wounded, | and offered I was To Othin, myself to myself, On the tree that none | may ever know What root beneath it runs.”

Hávamál 139, translated by Henry Adams Bellows

There’s something fascinating about a god sacrificing himself, and to himself. If I ignore all the other things the Gallows God did, he may be my favorite mythological deity — for his cunning, his wisdom, and his constant pursuit of knowledge at all costs. 139 is just a short stanza in a poem of 165, but the story it contains (or more precisely, briefly begins) is always retold with significance. I don’t think I’m the only one drawn to it.

There are so many lines in The Razor’s Edge I wanted to copy down that I never got around to doing it. I don’t even have the book with me right now, but while looking up a quote I came across this, which was something I had dog-eared in my copy, although it had slipped my mind until now:

“I only wanted to suggest to you that self-confidence is a passion so overwhelming that beside it even lust and hunger are trifling. It whirls its victim to destruction in the highest affirmation of his personality. The object doesn't matter; it may be worth while or it may be worthless. No wine is so intoxicating, no love so shattering, no vice so compelling. When he sacrifices himself man for a moment is greater than God, for how can God, infinite and omnipotent, sacrifice himself? At best he can only sacrifice his only begotten son.”

The Razor’s Edge, W. Somerset Maugham

It’s really the last two sentences that I want to point out, but I like the paragraph in general. I don’t think it quite explains why the sacrifice of the Raven God (I’m not sure whether to call him Odin or Othin so I’m using names everyone agrees on) is so compelling, as the Norse gods are quite different from the monotheist Christian God (the world doesn’t end because the Allfather dies, whereas it’s a much scarier thought that God could die), but there’s certainly some insight in this.

0 notes

Text

The Man Who Never Was

‘You haven’t a thing to stand on, Lado. There’s no doubt of it: Jessie Pidd was well known around town for many years.’

‘How many years?’ asked Lado.

‘Nobody is quite sure. Estimates run from five to fifty years.’

‘Do the descriptions of this non-man agree?’

‘All agree in calling him nondescript.’

The Man Who Never Was, R.A. Lafferty

I didn’t quite understand the mentions of “special power” at the beginning and the ending. I also didn’t quite understand what the author was getting at. But I enjoyed the story a lot. Although I don’t think I got the full gist of the main concept that was being explored, I liked what I did get — suggestions forming ideas, ideas forming stories, and when everyone around you agree to that story it becomes reality. The progression was paced and written really well. It’s one of those stories with a reveal that makes you look back and realize there were hints all over the place. It’s actually kinda dark, but the light, rustic tone of a western town is consistent until the end and I got a few good laughs.

“There is some mistake, we said. This is Springdale. You must be looking for Springfield clear in the other part of the State. A previous hearing you say? And only the day before yesterday? There must be some mistake. And the papers in your briefcase there? I bet that is the case the boy just ran off with. No, we don’t know who he was. We don’t know who anyone is.”

The Man Who Never Was, R.A. Lafferty

0 notes

Text

The Billiard Ball

“Suppose that, instead of trying to lift the indenting mass, we try to stiffen the sheet itself, make it less indentable. It would contract, at least over a small area, and become flatter. Gravity would weaken. And so would mass, for the two are essentially the same phenomenon in terms of the indented Universe. If we could make the rubber sheet completely flat, both gravity and mass would disappear altogether.”

The Billiard Ball, Isaac Asimov

I like it a lot better when sci-fi authors actually try to explain the science of things. For me, it’s just more enjoyable to read about the possibilities of science as opposed to the consequences of science. And if a story manages to have the knowledge and imagination to explore both, I’m all for it.

I really liked The Billiard Ball. The science and the drama are certainly integrated well — the science is the cause of the conflict, the instrument of the climax, and the solution in the resolution. It’s not simply a plot device to put the characters in a certain situation, and I love sci-fi that uses science so cleverly like this.

I will now try to stop repeating “science”......

Knowing what little I know of Asimov, I went in expecting something big-scaled and introspective of humanity or the sort, and was pleasantly surprised when the universe-altering idea of anti-gravity is explored through the comparatively diminutive (another unfamiliar vocabulary) relationship between an academic and an inventor.

The suspicious reporter as the narrator is a decent choice — an insightful observer, yet not close enough as to leave everything unambiguous and therefore spoil part of the fun. After all, what’s the point of having a murder if not to introduce an element of suspense or mystery? However, I also thought that the relationship between the narrator and the main actors is a little too distant. The reporter takes the role of the outsider (ie. the reader) that gives other characters a reason to dump exposition, but he is also an insider with enough knowledge to introduce the reader to the workings of the world of the story. It’s just that, in this case, I wanted to connect with James Priss (the Einstein of the time) and Edward Bloom (the Edison of the time) because I was engaged in their character and rivalry, but it’s hard to do because the narrator isn’t personally familiar with either.

Even with the intriguing personalities and plot, it almost felt like Asimov crafted a story around a scientific theory. The story ends a little abruptly, as if the non-science part of the conclusion isn’t important. This isn’t to say the story wasn’t tied up well. I was waiting for the accusation at the beginning of the story to play out more, although what it has is just enough.

This short story made me want to start studying physics.

Also I still have no idea what the difference between billiard and pool is.

0 notes

Text

A Legacy of Spies

“Or put another way: how much of our human feelings can we dispense with in the name of freedom, would you say, before we cease to feel either human or free? Or were we simply suffering from the incurable English disease of needing to play the world’s game when we weren’t world players anymore?”

A Legacy of Spies, John le Carré

I can’t say I’ve read much of le Carré: Call for the Dead, The Spy Who Came in from the Cold, Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy, and Smiley’s People, but they were enough for me to understand the plot and main idea from A Legacy of Spies. I have never actively sought out a le Carré book to read. They were all recommended to me, and I appreciate the intricacies of the stories, the craftsmanship of the language, and the complexity of the characters. But whether because spy novels aren’t really my thing or that most of the time I have to read le Carré’s books twice to wrap my head around everything, I just can’t quite get into them. That aside, I still enjoy these books even though I may not get as emotionally attached to them as with The Lord of the Rings.

A Legacy of Spies has the form of Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy in that it’s largely told through flashbacks and file-reading, and the ending of Smiley’s People in that it’s almost anticlimactic and a little unresolved. This book ultimately ties the main events of Smiley’s world together and as the plot is a matter of reconciliation of Peter Guillam’s past as well as Smiley’s, it’s also a coalescence of ideas as well as a reassessment of those ideas that appeared in previous books — friendship, betrayal, love, humanity, innocence, measures, ideals...... What was it all for?

“For world peace, whatever that is? Yes, yes, of course. There will be no war, but in the struggle for peace not a stone will be left standing, as our Russian friends used to say.”

A Legacy of Spies, John le Carré

One of the things I love about le Carré’s spy novels is that the reader becomes solely fixed on the mission. The abstractness behind the great big why of the mission is not purposefully dismissed, but as we are following the actions and minds of the agents in play, capitalism vs communism and all that sort of thing becomes trivial and a distraction to tangible stakes. The characters that hold an ideal above all else eventually find themselves dead or their ideals so far from reality as to justify their deeds. The place to go deeper into this subject is The Spy Who Came in from the Colder, where Alec Leamas is asked what he believes in, first by Liz Gold, and second by Fielder. But we’re talking about A Legacy of Spies here and I don’t have The Spy Who Came in from the Cold at hand.

When I first finished Call for the Dead, Smiley struck me as a man whose humanity and care for humanity stood out as his guiding principle. His fury towards those who harm innocents and dedication to preserving life made me think that he has the most down-to-earth yet spiritually high-minded ideal of all, if it could be called an ideal. His involvement in The Spy Who Came in from the Cold shook this image a little bit, but the characterization in Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy showed that noble side again, and it was this principle of Smiley that made the showdown between him and Karla in Smiley’s People work with impact — the fanatic was brought down by his own humanity, while the humanist threatened the unwitting to attain his goals.

So who is George Smiley and what does he fight for? After all that time with him, whether we are Peter or a reader, it’s still hard to figure out.

“You’re all sick. All of you spies. You’re not the cure, you’re the fucking disease. Jerk-off artists, playing jerk-off games, thinking you’re the biggest fucking wise guys in the universe. You’re nothings, hear me? You live in the fucking dark because you can’t handle the fucking daylight.”

A Legacy of Spies, John le Carré

I want to use that last sentence as an accusation leveled against the Assassin’s Creed.

Anyhow, it was at this point in the book that the main idea and the deeper-level conflict comes into full view.

“Legacy” is a word that had often given my fantasy-loving heart a twang. It implies grandeur and awe, endurance and continuation, heroics and epics, a sort of sublime that comes from history. But the legacy of these spies is a dark one. Their monuments are built with lies, their heroes are thieves, deceivers, and even murderers, their stories are either sealed in secrecy or tampered and destroyed. It is a legacy not to be gloried nor passed down. The past is brought into the open to be answered for.

And Smiley answered:

“I’m a European, Peter. If I had a mission — if I was ever aware of one beyond our business with the enemy, it was to Europe. If I was heartless, I was heartless for Europe. If I had an unattainable ideal, it was of leading Europe out of her darkness towards a new age of reason. I have it still.”

A Legacy of Spies, John le Carré

I’d like to think that Smiley’s “new age of reason” is one where people cease to put ideals above human lives and use “the greater good” as a justification.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

How to Justify a Private Library

“I believe that, confronted by a vast array of books, anyone will be seized by the anguish of learning, and will inevitably lapse into asking the question that expresses his torment and remorse.”

How to Justify a Private Library, Umberto Eco

I like to be in the library not because I have a fervent passion for reading, but because I love browsing. Also being in the library sometimes does pressure me into reading.

I have gathered a small collection of books over half of which I have not finished. Paul Theroux once said that he mainly reads from the library (or something along those lines), Qing Dynasty writer Yuan Mei wrote a short but famous piece (the whole of which I had to memorize in 8th grade) which argues “A book that is not borrowed will not be read,” and people I’ve known with private libraries think it’s only necessary to keep anthologies and reference texts and a couple of perennial (new vocab, not sure if I’m using it right) classics on their shelves and give the rest away so that other people can encounter the good books that benefited them. Most of the books displayed in a private library are usually not fully read. I guess that’s okay. It’s nice to be surrounded by books. As long as I don’t get into the territory of buying heavy, sad Russian novels simply for the sake of display, I’ll be tsundoku-ing as much as I want.

And while looking up “tsundoku” to see if my understanding of the word has been proper, I found a quote lots of articles on the subject have used that I might as well put down here:

“Even when reading is impossible, the presence of books acquired produces such an ecstasy that the buying of more books than one can read is nothing less than the soul reaching towards infinity......We cherish books even if unread, their mere presence exudes comfort, their ready access reassurance.”

Alfred Edward Newton

0 notes

Text

The Lucky Strike

“He was on the flight, no way out. Now he realized how easy it would have been to get out of it. He could have just said he didn’t want to. The simplicity of it appalled him.”

The Lucky Strike, Kim Stanley Robinson

↑ Sigh...... That hit me, but I’ll probably continue to say “yes” to everything and regret all of my life choices as, time and time again, I wait for the awful fulfillment of my agreement.

Anyhow, a little after this quote, in the same paragraph, is something less relatable but more crucial to the main idea of the story:

“Now there was no way out. It was a comfort, in a way. Now he could stop worrying, stop thinking he had any choice.”

The Lucky Strike, Kim Stanley Robinson

I found The Lucky Strike in Terry Carr’s Best Science Fiction of the Year (1985). A short story surrounding the bombing of Hiroshima, published about four decades after the historical event and the publication of John Hersey’s book. I was a little confused as to how it’s considered as science fiction, since the story takes place in the past and no time travel or alien gimmick is involved. The setting and the characters are all realistic and in that respect I thought the story should be categorized as historical fiction.

Robinson crafted the narrative around the character of Captain Frank January, a bomber tasked with the deployment of the atomic bomb. The larger half of the story is spent on build-up. January gets ever more sickened at the thought of killing hundreds of thousands with a flick of a switch in his hand, and entertains the idea of disobeying orders or sabotaging the strike. The pressure from his fellow men on the strike team (some who are more than happy to be on this particular mission), and the infeasibility of the solutions he came up with, deter him from backing out. And like the real bombers of WWII, he attempts the reasoning that it was Japan that started the war, that this strike would prevent the death of even more people, though that does little to resolve his conflict.

At this point the story seems to be a finely imagined character study that alludes to the deeper exploration of morality and consequence, a magnifying glass held to a small but important speck in history. However (SPOILER), just as you think history is about to take its course and the rest of the story would be spent on more inner monologues, Frank January deliberately misses the city, and the atomic bomb was never dropped on Hiroshima.

The twist made the story great, and although I’m still inclined to think it’s historical fiction, I guess the alternate history was what made it science fiction. While most alternate history stories focus on the grand picture of the new future, The Lucky Strike continues to follow January, a man now resolute, albeit miserable. Disgraced and condemned, he stays firm in his belief that he did the right thing, that bombing an entire city is unnecessary. And in this world, his decision made an impact. In his time, he is not hailed as a hero and meets his end facing a firing squad, but the melancholy ending shows a glimpse of the future, where January’s legacy is praised and his name becomes the front of an effort aiming towards denuclearization and peace. I’m glad Robinson didn’t give January a happy end — the conclusion has the right amount of real-world dismalness that gives tangibility to the belief the story imparts.

The Lucky Strike ultimately conveys the idea that each individual’s actions can make an impact, and the idea that while we like to distance ourselves from the bad decisions and actions — the general shakes off his guilt by not having his hand on the trigger, and the soldier dismisses his responsibility by relinquishing himself to orders — there is always a choice, a choice to do the right thing. While I generally dislike literary analysis and, as you can probably see from the previous sentences, am in no way good at it, I think every part of this story is worth looking into. The details made the story work. The pieces from January’s childhood further humanize the character and at the same time relate to the big story and theme at hand. There is not a sentence that is redundant. Foils to January, such as the strike team, the scientist, and the firing squad, add more depth to the world, create conflicts that make the narrative compelling, and present the other side of the argument. While a lot of time is spent inside January’s mind, you can still feel the world moving about him in its own way, obliviously pressuring in on him.

I didn’t start this out as a review, and it would be a mistake to take this as a review. I really liked the story and wanted to write about it, talk about the memorable parts, preserve the feelings that came from finishing the last paragraph — sadness but also an elevated sense of hope. Moreover, the writing is fantastic, and I wanted to copy down some of my favorite parts.

“They were having a good time, an adventure. That was January’s dominant impression of his companions in the 509th......His mind spun forward and he saw what these young men would grow up to be like as clearly as if they stood before him in businessmen’s suits, prosperous and balding. They would be tough and capable and thoughtless, and as the years passed and the Great War receded in time they would look back on it with ever-increasing nostalgia, for they would be the survivors and not the dead. Every year of this war would feel like ten in their memories, so that the war would always remain the central experience of their lives — a time when history lay palpable in their hands, when each of their daily acts affected it, when moral issues were simple, and others told them what to do — so that as more years passed and the survivors aged......they would unconsciously push harder and harder to thrust the world into war again, thinking somewhere inside themselves that if they could only return to world war then they would magically be again as they were in the last one — young, and free, and happy. And by that time they would hold the positions of power, they would be capable of doing it.”

The Lucky Strike, Kim Stanley Robinson

I always thought “Men who have seen battle are often among those who hold life most dear.” January is probably a man like that, but his companions are not part of the “often”. Reading the paragraph I also thought of All Quiet on the Western Front, but the young men in that story thought they wanted to fight and die in glory, only to see in the trenches that the reality of war is far from what they have imagined, and that they had never known what they wanted in the first place. Writing from the 1980’s, I wonder if Robinson was referring to any persons at the time — men who were in WWII in their twenties and went into politics or rose in the military in their sixties, mongering war and saying, “When I was your age......” But I think that as the living memories of the the great wars pass away and people forget the horror, the new generation of leaders may be more inclined to start war unaware of what they’re getting into. The old people that support wars nowadays seem to mainly come from a position of nationalism and prejudice.

Anyhow, let’s end with something more......inspiring.

“And he told him about the game he had played in which every action he took tipped the balance of world affairs. ��When I remembered that game I thought it was dumb. Step on a sidewalk crack and cause an earthquake — you know, it’s stupid. Kids are like that...... But now I’ve been thinking that if everyone were to live their whole lives like that, thinking that every move they made really was important, then......it might make a difference.’”

The Lucky Strike, Kim Stanley Robinson

0 notes

Text

Portrait of King William III (Opening)

“I never can look at those periodical portraits in The Galaxy magazine without feeling a wild, tempestuous ambition to be an artist.”

Portrait of King William III, Mark Twain

There have been way too many times where I take the same sort of ambition for passion and thought to make many of my ideas into words, picture, music, and code, but in the end fall short of all. I give up, then find my hope rekindled in another work of such medium, only to be distracted or disappointed.

Once upon a time there was a landlord who saw his neighbor’s new mansion and really liked it. He hired the same builder and asked him to construct a house for him exactly like that. One day he visited the construction site, and was surprised to see the workers digging into the ground. He asked the them what was going on, to which the builder replied that they were constructing the foundation. The landlord was baffled. “What for? I only want the second floor of the house.”

I’m like the landlord, dreaming of the floor in the air with no technical skills to prop it up. I did try learning, but couldn’t commit, or was too lazy to follow through on anything. I keep on thinking that I would eventually be equipped with the abilities to make my ideas take form, but at the rate I’m going, I’m afraid the dreams and ideas would be gone by then, and my imagination would be more boxed in.

The quote really doesn’t have anything to do with all of this, but it struck me when I came across it and this is why.

0 notes