Nerdy stuff? Me being done with misinformation and anti-education sh*t? Yell knowledge into void? Yes.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

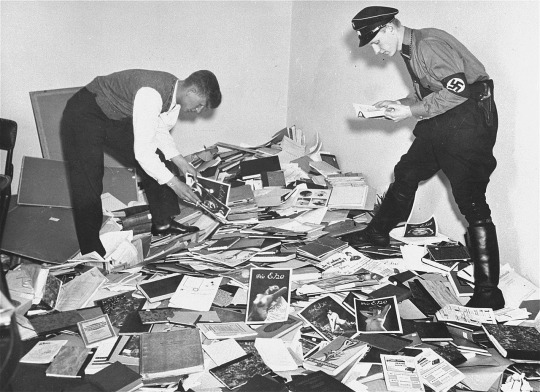

And this is why we talk about not just history, but the history of history. Also, why it's a good idea to check for contemporary and/or primary sources.

if you're just joining us, george takei is having to educate jk rowling on holocaust denial

80K notes

·

View notes

Text

A More Complete History of America

Section 1 - When to Begin?

Folsom, Clovis and The First Debate

Part 2 - Clovis

There is some dispute on the true type site of the predecessor of Folsom. The Type Site, the first site to be formally described to a scientific audience, often dictates naming rights. This leads to some academic saltiness and state rivalry. In the interest of fairness, we’ll actually start in Colorado.

Along the South Platte River, southwest of the small town of Milliken, Colorado once stood the Dent Railroad Depot. In 1932, strong Spring rains exposed several very large bones in a sandstone gully west of the tracks.

The son of the Depot’s manager informed his geology professor, Jesuit priest Conrad Bilgery. He took some of his students to the site in September of that year, where Father Bilgery determined the bones were that of a mammoth and contacted Jesse D. Figgins.

Yes. The same Figgins that was the Director of the Colorado Museum of Natural History.

Figgens sent a museum staff member to excavate the remains, though Father Bilgery and his students were allowed to assist. In the end, 13 partial skeletons from 5 adult females and 8 young mammoths were sent to Denver, along with two intact stone points.

Figgins published the find in the Proceedings of the CMNH in 1933 - the museum bulletin essentially - describing the points as belonging to a Late Ice Age culture.

Sadly, internal museum publications don’t count. I don’t make the rules.

In 1929, EB Howard was part of Alden Mason’s Southwestern Expeditions as a representative of the University Museum of Philadelphia. They had come to the Guadalupe Mountains west of Carlsbad, NM to search for archaeological sites, and were quickly directed by local Bill Burnet to a cave locally known for its artifacts.

It's unclear how long the predominantly white local population had known about the cave. Burnet reported it had once been sealed, but he and his brother had busted through the stacked stone wall. At some point, they had dug 3 or 4 holes,each about a yard deep. Beads, pieces of sandals, hide, and several baskets, one containing charred bones (which may have been human remains as cremation was practiced in the region at various times in the past) were all removed.

Still, the site was relatively intact. The pits had been dug straight down, and, aside from stones and debris being moved at the surface, most of the ground appeared undisturbed.

Excavations began in 1930. As Howard and the team had hoped, by the time their trench hit that 3 ft deep mark, they were in undisturbed soils. Like most caves and rock shelters, Burnet had little stratigraphy, or distinct soil layers, to go off of and they were about 30 years from widespread radiometric dating, so they attempted to date the cave using the common method of the day: identifying Cultural Horizons.

This meant, quite simply, looking at whatever turned up in their trench and trying to identify the age of that layer by the artifacts it contained. More baskets, sandals and bags found in those between about 1.5 and 3ft down indicated a Basketmaker Culture (an uncreatively named Pueblo precursor). They found several burials, which were likely the reason the cave had been sealed.

Above the Basketmaker layers were no distinctive artifacts beyond what had been scattered near the surface by looting. Again, the fact that the cave had been closed off to all but pack rats and other rodents had stopped later people from using it.

It was about 2 feet below the burials, however, that EB Howard made a more unexpected discovery. Among the bones of bison and musk-ox, some of them charred, were thick lenses of ash and charcoal. Hearths. Along one of these rested a fluted stone point that Howard described as Folsom-like. Several bone awls for sewing hides or making beads were also recovered.

Howard was very careful in his initial report of the site in 1931. He made a point of describing the interior of the cave, its geology, condition, and included multiple sketches of the layout. He reiterated that the cave had been sealed, hiding it for generations. He discussed how pack rats could have gotten in and built nests and middens at the surface, but that there was no evidence of burrowing or middens near the remains or below them. It was doubtful, Howard expressed, that the stone point or awls could have been deposited so deep by rodents.

EB Howard took that point to the 1931 Pecos Conference. Among the people he showed it to was Frank Roberts of the Smithsonian.

Cannon AFB was once a small local airstrip. By the early 1930s, it had been named the Clovis Air Field and was expanding. Some of the gravel for the new road construction came from nearby Black Water Draw, a seasonally dry valley crossed by small channels from the infrequent rains located along the Llano Estacado Plateau. The Dustbowl had already stripped away some of the surface layers, and while quarrying workmen revealed, you guessed it, large animal bones. They also turned up a large tooth and a stone point.

In 1932, as he was finishing work at Burnet Cave, it came to the attention of EB Howard that points like those at Folsom had been found in the area. He and his team swung by Clovis to look around, guided by locals AW Anderson and George Roberts, who themselves had taken a keen interest in the site.

The first point had been found by a workman with the gravel company, along with a mammoth tooth, when they had first reached the blue-gray layer at the gravel pit. This was the point that George Roberts had notified Howard about. Roberts had secured the point from the workman and shown it to Howard when he arrived in Clovis.

“The workman, whose honesty I do not question, showed me the spot where he had ploughed up the tooth and this artifact, and there is no doubt in my own mind that they both came from the blue sand on the west side of the gravel pit.” EB Howard

The point itself had been broken long ago, before the workman had uncovered it, as evidenced by the lime crust and was similar to the points from Folsom and about 4 inches long and 2 ¼ in wide, and “extraordinarily thin - ⅛ in at its maximum thickness”.

The summer field season was almost over, but Howard had the opportunity to explore Black Water Draw and view some of the artifacts and bones that had been found. That fall, machinery uncovered another mass of bones in a layer of blue-gray sands below the gravel layers.

Like at Burnet Cave, Howard made detailed notes of the site and its surroundings. Black Water Draw as a whole was dotted by the remains of ancient lakes, ponds and channels. On its western edge and near the Texas border, there were still a few alkali spring ponds. Likely, the Draw had once been a tributary of the nearby Brazos River, or at least drained into it. Where the gravel pits had been dug revealed a clear view of the geologic layers or strata to well below the bone bearing layers.

The bone layers, blue-gray sandy clay, were near, but not at the top. These were water deposited and held many species of diatoms, tiny water dwelling animals, which still live in fresh and saline waters. These diatoms, and the bones of the mammoths and bison, allowed Howard and his team to determine that the blue-gray sands had been deposited in the late Pleistocene, near the end of the Ice Age.

Howard could not begin a full excavation until the summer field season of 1933 and spent the next 4 years in Clovis. On the east side of the gravel pit a flint scraper and charcoal, presumably from a campfire, were among the bones of extinct bison, the first in situ objects found. More scrapers and knives were uncovered near the pit. In a section of Blackwater Draw Howard named the Anderson Lakes, a thick lense-shaped layer of charcoal contained the charred bones of bison (found all over the Lakes), small mammals and birds and a selection of blades and shapers. None of the Anderson Lakes artifacts appeared to be of the “Folsom-type”, even though they came from the same deposits of blue-gray sands.

No mention of a new “Clovis-type” appears in Howard's 1935 report. Instead it included a great deal of discussion of the geology, such as the diatom studies, and theories of how such a site could have come to be. It's here that Howard relays a story from Prentiss Gray, who had studied bison and in 1887 had observed a herd of some 4000 attempt to cross the South Platte River when it was low. “Soon the leaders were stuck in the mud, those behind, pressed forward by the herd, trampled over their struggling companions until the whole bed of the river a half mile wide was filled with dead and dying buffalo. This habit of stampeding was a habit of the wild buffalo.” Howard also shared similar accounts of antelopes in the Congo and Guanacos in Patagonia who had trampled each other or become trapped in frozen mud.

Howard also devoted part of his report to explaining honestly that he, his team and even the other prominent scientists they had brought to Clovis or otherwise consulted, can't say for certain that there had been no mixing of artifacts and layers at the site. Firstly, at and near the windblown surface, were scattered Yuma style points. These were known to be old - no contemporary peoples were known to use points quite like them, but they were from long after the Ice Age. Other points, some Yuma, some of other styles but all of that same old but still recent manufacture, and some pot sherds had been recovered from layers above and within the blue-gray sands. While never found directly alongside the older, unidentified and Folsom-like tools, these finds cast a shadow of doubt as to the antiquity of the flints.

It was in 1937 that JL Cotter, Howard's primary partner on the excavation, published the final report on the The Occurrence of Flints and Extinct Animals in Pluvial Deposits near Clovis, NM (part IV). Though he did not formally classify the points as a new type, this is where they start being referred to as a distinct style that had only been reported before from the Dent Site and Burnet Cave.

By the 1950s, the fluted points had become called Clovis Points and their style and method of manufacture was known to be a precursor to Folsom technology. Radiometric dating, though it would need future calibration and refinement, would first be done in the 1950-60s, returning dates of nearly 10,000 years before present, well within the known range of the late Ice Age.

Hrdlicka died in 1943, and would never accept the findings at Folsom, Clovis or anywhere else.

Sources and further reading/listening:

“THE INITIAL RESEARCH AT CLOVIS, NEW MEXICO: 1932-1937.” Plains Anthropologist 35, no. 130 (1990): 1–20. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25668959.

Cotter J. L. 1937 The Occurrence of Flints and Extinct Animals in Pluvial Deposits near Clovis, New Mexico, Part IV: Report on the Excavations at the Gravel Pit in 1936, Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, 89, pp. 1–16

Jesse D. Figgins, “A Further Contribution to the Antiquity of Man in America,” Proceedings of the Colorado Museum of Natural History 12, no. 2 (1933).

Brunswig, R. (2016) The Dent Site: A Late Ice Age Encounter on the South Platte River

for the online Colorado Encyclopedia

Steeves, P. F.C. (2022) The Indigenous Paleolithic of the Western Hemisphere University Press Audiobooks

Meltzer, D.J. (2011) First Peoples in A New World: Colonizing Ice Age America University Press Audiobooks

Adovadio, J.M., Page, J., (2022) The First Americans: In Pursuit of Archaeology’s Greatest Mystery Tantor Audio

Hamalainen, P. (2022) Indigenous Continent: The Epic Contest for North America

Howard, Edgar B.. "Burnet Cave." The Museum Journal XXIV, no. 2-3 (June, 1935): 62-79. Accessed March 13, 2024. https://www.penn.museum/sites/journal/9515/

#archaeology#paleolithic#clovis#prehistory#history#found the format buttons#still need to stop doing this on phone

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

I honestly didn't think anyone would read or comment so fast. Ty for the notes and I guess this means I should format things better.

I did get a lot of editing done today, fixing weird flow since I finally got a chance to read aloud. Toddler makes this difficult, but got Folsom fixed up and Clovis finished (probably needs another read through to be sure).

Still, haven't crapped out yet.

0 notes

Text

Edited and formatted 3/12/24

A More Complete History of America

Section 1 - When to Begin?

Folsom, Clovis and The First Debate

Part 1 - Folsom

“PaleoIndigenous people wrote the story. Eleven millennia later, a Black American recognized the story but died before anyone recognized him. A blue-collar, white American shared the story with local scientists and followed their orders to dig it up. When he found projectile points and bones in situ, his Denver-based supervisors assumed control of the project, but only until the final arbiters of archaeological knowledge arrived on scene to legitimize the data and the narrative.”

Bonnie J Pitblado, 2022

Located in northeastern New Mexico, Folsom is not easy to find on most maps, especially before you could just Google it. It was almost removed from maps completely in the year 1908 when a powerful, late summer monsoon storm caused the Dry Cimarron River -both its name and usual condition - to overrun its banks. The NYT Aug. 29th headline read “CLOUDBURST DROWNS 15 IN NEW MEXICO; Town of Folsom Caught in Torrent and Houses and People Swept Away”. Local and later sources would place the death toll at 17.

Among those lost was Sarah “Sally” Rooke who had arrived in Folsom at the age of 65 a few years before to visit a friend and never left. She had become a telephone operator at the Folsom exchange and, on the day of the storm, the 27th, she had received word from another operator upriver reporting the largest flood they had ever seen. Sally began making phone calls to the town’s few hundred residents, warning as many as she could of the incoming wall of water. She would give her life for this task - her body would not be found until the following Spring, 8 miles downriver among the debris, with the handset purportedly still clutched in her fingers.

A plaque in her honor now stands near the Folsom Museum, as well as a historical marker erected along the town’s Main Street (also NM325). In 2009, she was designated a “Heroine of New Mexico” for her bravery and sacrifice.

The Town of Folsom eventually began to rebuild, but it never fully recovered. In the coming days and weeks, as it slowly pieced itself back together, the foreman of the nearby Crowfoot Ranch was also assessing the damage.

George McJunkin had been born most likely in 1951 (a few sources list it a few years later) on a ranch near Midway, Texas. Like most African Americans of his time, George, and his parents, were enslaved. He’d grown up on the same property, and with the same owner, as his father, working with horses, cattle and in his father’s blacksmith shop. He probably picked up Spanish pretty young, perhaps from the Vaqueros who were frequently hired for cattle drives at the time. When the Civil War ended, and George was finally free, he was a teenager. The exact timeline is unclear, but it appears he very swiftly joined one of those long cattle drives out of Texas and never returned to Midway. He became an expert bronc buster and went on bison hunts. And, during all this, he began to learn to read and write, perhaps trading his smithing or horsebreaking skills for lessons.

With the education that had been so long denied to him finally in hand, George began reading everything he could get his hands on. He seemed especially fond of the natural sciences - field guides and books on the animals, plants and landscapes of the West.

By 1908, George McJunkin was a foreman at the Crowfoot Ranch and appears to have been well respected by his small community. After the flood, he was searching for lost cattle, broken fences, and generally noting the other impacts of the disaster.

He and a friend and fellow ranch hand were riding along the Wild Horse Arroyo when George spotted something that was at once common and unusual.

When the rushing waters had cut back the sandy banks of the arroyo, they had exposed a number of very large bones. After stopping to examine them and working a few more loose, McJunkin realized he had to be looking at the ribs of some giant animal. George McJunkin knew about animals, especially cattle, which these bones were too large for and buried much too deep and bison, which these bones were still too large for. He would likely have read about the extinct Ice Age Giants that had once roamed the Earth, the mammoths and saber tooth cats. It isn’t clear if he knew the name Bison antiquus, but he certainly knew that the bones he had uncovered were not those of anything that was still around.

He collected several bones and made a note of the location. The bones would eventually come to sit on his mantlepiece, alongside his collection of other fossils, rocks and crystals. George wrote letters and tried to garner scientific interest and would spend the next 15 years showing bones and describing the find and its location to friends, acquaintances, and anyone else he thought might be intrigued. One of these was Raton blacksmith and amateur naturalist Carl Schwachheim.

In what almost seems like a fated encounter, George had only stopped in to have a wagon wheel repaired. While there, he noticed the fountain that stood in front of the shop and the enormous pair antlers that topped it. He said something like;

“I've got some bones that would fit them antlers.”

Carl was immediately intrigued with the story of George's “Bone Pit”.

Sadly, George failed to attract any professional scientific interest to his find. In a story I can't find the original source for, it seems he tried one final time in 1918, taking the son of the ranch’s owner, Ian Shoemaker, out to the site. They pulled a few additional bones from the site (but not any points) and mailed them and a letter to the Colorado (now Denver) Museum of Natural History.

In December of 1922, George McJunkin died in his room at the Folsom Motel. He never had children, but was buried with a stone marker at the town cemetery. At some point, they added a modern headstone. In 2019, almost 100 years after his death, he was inducted into the Cowboy Hall of Fame. According to a July 13, 2020 article by Amanda Mathers,a curator of collections at El Rancho de Las Golondrinas, the last time she visited the grave, there were fresh flowers. She left some more.

December 10, 1922: “Went to Folsom and out to the Crowfoot Ranch looking for a fossil skeleton. Found the bones in arroyo ½ mile north of ranch and dug out nearly a sack full which look like buffalo and Elk. We only got a few near the surface. They are about 10 ft. down in the ground.”

(Carl Schwachheim’s Diary)

That winter, Schwachheim set out to Wild Horse Arroyo to attempt to locate and document the site. Since their fateful encounter with the wagon wheel several years earlier, Carl had never forgotten George or his bones, but had never been able to make it out to the site as he didn't own a car and traveling to Folsom by wagon had been difficult before the flood. Still, it seems he had been planning the expedition for some time. George had also told Fred Howarth, a local banker and friend of Carl's, and by the time of their trek the party also included Rev. Aull of St Patrick Catholic Church, amateur taxidermist James Campbell and grocer Bonahoom, all of Raton. With the help of Aull and Howarths cars, they set out. Perhaps, had he not fallen ill and passed earlier that year, or had they made the trip sooner, George McJunkin would have been with them.

They filled a gunny sack with bones, and that evening when they returned to Raton, Carl and James sat around the Campbell kitchen table digging through paleontology books trying to identify the remains.

In 1925, Shwachheim also began sending out letters. Most went unanswered or ignored, but one made it to the desk of then Director of the Colorado Museum of Natural History, Jesse D. Figgins. The next January, when Howarth had to deliver cattle to Denver, he hired Carl and they met with Figgins to show him the bones.

The bones made it to Harold Cook, the museum's Curator of Paleontology, who identified them as having belonged to Bison antiquus. Standing nearly twice as tall as modern bison, this species had gone extinct after the retreat of the glaciers.

By March of 1926, Figgins and Cook had decided they wanted to see the site for themselves, and on the 7th Carl led them there. It was a good find. Figgins had been wanting a specimen to mount for display. He and Cook hired Carl to begin preparing the site for excavation by removing as much of the overlying material as possible and clearing the surrounding area.

That Summer, Figgins sent his son Frank to supervise Schwachheim as he began to uncover and remove the bones as an assistant. It must have been a dream come true for the man who had long been an avid amateur fossil collector.

July 14th, they uncovered the first broken point, a “dark amber colored agate of very fine workmanship” (CS diary). It was not in situ, but laying near the base of an animal's spine. While not embedded, Carl noted that it had been found at least 8.5ft down, directly under a medium sized oak tree, “showing to have been there a great length of time”. About 2 inches long, the point had been broken off. The find was reported to Jesse Figgins, and they spent the rest of that season sifting carefully for any points in situ and, if they found any human remains to “under no circumstance move them” but to inform Figgins at once.

Figgins did have reason to be cautious. At this time famous physical anthropologist and Smithsonian Curator Ales Hrdlicka and many other prominent scientists placed human arrival in the Americas at around 3000-4000 years ago and would hear no argument or evidence to the contrary. A few years before, in 1918, EH Sellards had announced his findings of stone tools found in association with extinct animals in Vero, Florida. William Henry Homles, also of the Smithsonian, called Sellards paper “dangerous to science.” He and Hrdlicka “thoroughly” debunked the site and others like it.

Figgins and Cook had actually been on the receiving end of one of these rebuttals. The year before Wild Horse Arroyo came to their attention, a site near the town of Colorado in the state of Texas called Lone Wolf Creek where another extinct bison kill site had been found, complete with projectile points. Cook had been dispatched to examine it in 1925.

Like Florida and another excavation in Kansas, no points had been found in situ or in place among the bones, and thus went unrecognized as legitimate by Hrdlicka and Holmes. They would only consider such a wild claim as Ice Age American Man if indisputable human artifacts - or better yet, remains, Hrdlicka loved collecting skulls for his research - were found in clear association with the remains of extinct animals, and only if the actual site was examined by them or other well regarded scientists to confirm the findings.

This was why Figgins wanted no human remains moved. If any were uncovered and moved away from the bison, it would be too easy to say that they had been deposited later, long after the animals had vanished from living memory. Notes and sketches, even pictures, were not going to be enough for Hrdlicka. Still, Figgins truly felt that the evidence of Ice Age Man in the Americas was mounting.

But why had this even been a question? And why were Hrdlicka and Holmes so seemingly personally offended by the mere suggestion?

By the time the first English speaking Colonists had arrived on the Eastern Coast of what is now the United States, the Spanish had been in the Western Hemisphere for over a century. In that time, great and wealthy empires had been found and conquered to the south, and waves of expeditions and settlement into the Gulf Coast and Southwest had already made a lasting impact on the Indigenous People.

The Eastern half of North America had already been severely depopulated by the time Jamestown and Plymouth were founded. Since that time, the Colonists had pushed ever westward, encountering Indigenous populations who had lived in the area since time immemorial and groups who were newer to the region, pushed there themselves as their homelands had been taken from them.

The Colonists also found the remains of villages and towns, many constructed amongst giant Earthen Mounds. Coming originally from the British Isles and Central Europe, the Colonists were reminded of Barrows, the earthen tombs of Stone and Bronze-Age peoples back home. When their tills, plows and shovels turned up pottery, copper artifacts and ancient bones, their suspicions seemed confirmed.

Although many Indigenous groups such as the Choctaw, Lenape and Ottawa still lived among the mounds, and the Spanish explorer de Soto had described densely populated Indigenous cities among the mounds of Mississippi only a century or two before, the English Colonists saw no connection between Native peoples and the builders of the mounds.

In their minds, the Colonists did not associate the Indigenous Peoples that they had encountered with metalworking. When they had first arrived and well into the Colonial Period, those same Natives had been eager for the iron tools brought by the Eurpoeans. They saw the Algonquian speakers using many types of baskets, but almost never ceramics. They knew the Indigenous people were skilled at working shell, antler, bone and certain stones and artfully decorated their tailored buckskins and bodies with beads and pendants, bracelets and necklaces. They had traded with them for pearls and the intricately carved stone pipes, exchanging glass beads, fabrics and copper pots.

There were also the burgeoning ideas of racial superiority and hierarchy, seemingly confirmed when Carl Linnaeus, in his seminal 1735 work, had categorized humans into four varieties. Darwin had not yet been born; Linnaeus and people of the time took the biblical perspective of a single creation for Man and all living humans being descendants of Noah's sons, but he felt that region and climate had caused changes in the attributes of the humans who dwelt there. This wasn't racism, not yet, if only because the term race was not yet used.

As more mounds in Eastern North America were dug up by treasure seekers, farmers and plantation workers, the Colonists and Europeans to see the artifacts and remains as those of an elite civilization, long gone. To some, they were evidence of Phoenicians or Egyptians that must have ventured to the new world. Perhaps the Aztecs had journeyed north at one point. The ancestors of the Indians must have come along later, as they showed no evidence of the level of advancement of the Moundbuilders. Perhaps they had even wiped them out. Furthermore, while in Europe human artifacts and remains were often found among Ice Age animals, none had been found in America.

In fact, some European minds argued, the entirety of the animal kingdom in the Americas was primitive and lacking, having clearly degenerated from that of the Old World. As long as they remained, the Colonists would degenerate into savages too.

These were fighting words, as far as Thomas Jefferson was concerned.

In his only published book, Notes on the State of Virginia (1785), Jefferson would describe the vast variety of new and unique plants, animals and cultures encountered just in that small region. In other writings, he would discuss the new discoveries of the entire continent and theorize as to what was yet to be discovered.

Extinction was not yet an accepted concept. Though no living Mammoths had been so far found in Eurasia, Jefferson believed that they might be found deep in the continent's interior.

Thomas Jefferson would also excavate a mound on his property, taking careful notes and examining the goods and remains he uncovered. He would publish the first archaeological description of a mound and postulated that they had indeed been built by the ancestors of Indigenous Americans in his book on Virginia. He also believed they must have crossed from NE Asia, somewhere around Kamchatka which had just been mapped.

His was a rare opinion and would remain so for centuries.

In Jefferson's time, it was believed the Earth could be no more than 6000 years old, as calculated by James Ussher in the mid 1600s. The ancestors of the Indigenous Peoples, whether they had built the mounds or not, had likely arrived around 3000-4000 years earlier, sometime after the Great Flood.

While the age of the Earth had been pushed to between 20-100 million years old by the beginning of the 20th century and ideas of evolution and extinction had become accepted by the scientific community, the idea that humans, or at least the Indians, were incredibly recent arrivals persisted.

Hence, the opinions of Hrdlicka and Holmes.

William Henry Holmes had no formal training or education in science when he went to Washington DC to study art. In 1871, he was reportedly sketching a mounted bird in the museum when he caught the attention of FB Meek of the Smithsonian, who hired him to sketch fossil and live mollusk shells for his paleontologists reports. Later, he would join the Hayden Survey as an artist where he sketched such sites as the Mesa Verde Cliff Dwellings and Yellowstone. His interests turned to archaeology by 1875, and he is well known for his illustrations of Ancestral Puebloan pottery. He was awarded an honorary Doctorate of Science by George Washington University in 1918.

The story of Ales Hrdlicka is a little more…well. A Czech immigrant, Hrdlicka had begun his studies and career in Medicine, but while working at an asylum he was introduced to the science of anthropometry.

In the centuries since Linnaeus described different varieties of Homo sapiens, and within decades of Darwin's works on evolution, racial science had begun to develop as a new field. Now, humans were placed into different races or subspecies. The leading question of the day was how many there were and what set them apart. The fact that Africans and the similarly black skinned peoples of Oceania often had heavier brow ridges, between those of Europeans and Cro-Magnons and Neanderthals, was taken to point to the primitiveness of their race, further evidenced by their lack of sophisticated technology. Peoples of Asia and the Americas must've lay somewhere in between. Detailed measurements of facial features, skulls, the length of limbs and their proportion to the body, all became important to determining what race a group or individual fell into.

Hrdlicka embraced this science, developing a classification system largely based on skull shape and characteristics. In his mind, Indigenous Americans, like all humans, could fall into one of only three categories - Caucasoid, Negroid or Mongoloid. The prevalence of characteristics of the last type led him to be another early proponent of the Beringian Hypothesis, though he saw evidence of the other races in various groups as well, with African features becoming increasingly common to the south and west.

He was also an enthusiast of the new science of eugenics.

As pointed out by archaeologist David Meltzer, Jesse D. Figgins was a card-carrying KKK member. He wasn't out to prove that contemporary Indigenous Americans had any Ancient ties to their land or classify them in any new way. He simply believed that humans had lived in the Americas during the Ice Age. Who they were or whether they were ancestral to later peoples was not important.

They still had to prove that humans had indeed been among those bison.

In November of 1926, Scientific American ran an article entitled On The Antiquity of Man in the Americas by Harold J. Cook. It included pictures of two of the recovered points. In 1927, Figgins had taken several of the bones and points to the Smithsonian to show the points to Hrdlicka and Holmes.

Hrdlicka had insisted that because they were not in situ, they could have rolled into the Bone Pit at any time, even during excavation.

Fortunately, on August 29th 1927, Schwachheim, still assisting at the site, made the find that would finally provide indisputable proof that humans had indeed been among those bison.

A clear stone point was embedded near a rib, both still trapped firm within the surrounding material or matrix.

Carl had rushed a letter to Folsom and that letter made it onto the evening train bound for Denver. Figgins sent a letter back instructing him to guard the point and not let anyone dig around it. Telegrams were dispatched to prominent scientists across the country, inviting them to come see the find in person.

Figgins, Vertebrate Paleontologist of the American Museum of Natural History Barnum Brown and Frank Roberts, archaeologist at the Smithsonian Bureau of Ethnology arrived on September 4th. A few days later came AV Kidder of the Carnegie Institution.

The assembled scientists agreed that the stone points and the bison were in clear association.

Hrdlicka was notably absent, though it is unclear if Figgins bothered to telegram.

The American Anthropological Association's December conference devoted a full symposia to The Antiquity of Man in America. Figgins and Cook were not invited to speak, and it was Roberts and Brown who described what they had seen at Folsom.

In fact, Figgins and Cook would not be invited to speak at any anthropological conference concerning the timing of human arrival in the Americas for the next 10 years.

Sources and further reading/listening :

Uncredited, (August 29, 1908) CLOUDBURST DROWNS 15 IN NEW MEXICO; Town of Folsom Caught in Torrent and Houses and People Swept Off in the Flood. RAILROAD BRIDGES DOWN Georgia and Carolinas Suffered Heavily -- Buildings in Augusta, Undermined, Collapse. The New York Times https://www.nytimes.com/1908/08/29/archives/cloudburst-drowns-15-in-new-mexico-town-of-folsom-caught-in-torrent.html

Sarah “Sally” Rooke Bio (ret. Mar 2024) New Mexico Women’s Historical Marker Program https://www.nmhistoricwomen.org/new-mexico-historic-women/sarah-sally-rooke/

Jackson, L.J., Thacker, P.T. (1992) Harold J. Cook and Jesse D. Figgins: A New Perspective on the Folsom Discovery, Rediscovering Our Past: Essays on the History of American Archaeology, Worldwide Archaeology Series, edited by Jonathan Reyman

Cook, H. J. (1926). The Antiquity of Man in America. Scientific American, 135(5), 334–336. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24976879

Pitblado, B.J. (2022) On Rehumanizing Pleistocene People of the Western Hemisphere American Antiquity 87(2), pp. 217–235

Meltzer, D.J., (1983) The antiquity of man and the development of American archaeology Advances in archaeological method and theory, pp. 1-51

Meltzer, D. J. (2005). The Seventy-Year Itch: Controversies over Human Antiquity and Their Resolution Journal of Anthropological Research, 61(4), 433–468. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3631536

Meltzer, D.J. (2011) First Peoples in A New World: Colonizing Ice Age America University Press Audiobooks

Raff, J. (2022) Origin: A Genetic History of the Americas Twelve Audiobooks

Fordham, A. (2023) The Extraordinary Life and Long Legacy of Black Cowboy George McJunkin KUNM https://www.kunm.org/local-news/2023-02-24/the-extraordinary-life-and-long-legacy-of-black-cowboy-george-mcjunkin

Hillerman, T. (1971) The Czech That Bounced: How Folsom was Saved to History New Mexico vol.50 nos.1-2, pp 25-28

Veltre, P. (2019 ) The Carl Schwachheim Story KRTN Radio

https://krtnradio.com/2019/07/11/the-carl-schwachheim-story-by-pat-veltri/

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Forward

Intent and Integrity

Look, I've been working on something like this, a great, probably exhaustive overview of American History for a long time. I was debating with myself if I had anything to add or present in a new way, but as more discussion on how history and science should be taught, if they should be taught, I said screw it and started outlining, researching and finally writing.

Then Some Bisexual Brit made a 3.5 hour long video and plagiarism and the (first Black female) President of Harvard stepped down amid allegations of plagiarism and suddenly the internet and the people of the US seemed to care a lot more about in-line citations.

So I began editing, revisiting sources, making sure any direct quotes or paraphrasing was marked as such.

During that time I read created pages of notes and dates and names and all the other things i, and everyone else, hated about how history was taught.

I kept watching other creators and finding little nitpicks that I didn't often comment on, and responded on subreddits discussing SW history or PaleoIndigenous peoples.

It was a few of those last ones that had me typing the first section of this and a few other bits.

I will never be satisfied with the editing. I'll always think there are too many or too few citations. I also know plenty of people don't care about proper citations, as long as the list of sources isn't simply copied from Wikipedia. If I try to make this to perfect, it will never be shared.

The whole point of research, of knowledge, is to share it. If I don't just do this, I may never post any of it in any form. This is not a perfect work, it may by its nature never be complete. It restates the research of others, repackages it, and presents it together. While researching, I spent time listening to several Audiobooks on the early Western Hemisphere and genetics, and I cannot say for sure that I have not quoted more than I meant to. I don't have page numbers, as I haven't grabbed physical copies, but I am including those books among the sources.

In the interest of academic integrity, I'm still going to say that this is all, here in the earliest sections, heavily sourced and influenced by the works of Paulette FC Steeves, David J Meltzer, Jennifer Raff, James M Adovasio, David Reich and Adam Rutherford. The particular works I draw from will be included in each section.

#history#archaeology#american history#science#how obvious is it this is all being copied from a large doc#is this how tags work#only lurked never posted before

0 notes