Detailing my work in IGB120 - Introduction to Game Design

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Assessment 3 Postmortem

Since for assessment 3, my group decided not to fully develop my prototype, I didn’t do most of the designing for our game, Quack Attack. However, throughout development, I did attempt to make changes where I saw fit to “chase the fun” and make the game as good as possible, so I will talk about that. Since we had a reasonable basis for a game, most of my design work was toward reaching the vision of our initial one-page design by solving problems that were originally overlooked. The Fullerton book talks about this in chapter 10 in its section on balancing. Balancing involves ensuring the gameplay is fun but challenging, meaning it never feels too easy, but it also never feels unfair.

One example of balancing was our removal of the “healing duck” In the original design, this duck would heal all enemy ducks around it. What we found in practice is that this didn’t work for our type of game. Quack Attack is meant to be a chaotic game, spawning hundreds of ducks and having the player kill them in quick succession. What this meant was that ducks would clump together, getting healed repeatedly by multiple healing ducks, making them feel very “bullet-spongey.” I think making choices like these is important in game design, even though they are tough, since we put so much time into designing and implementing the healing duck. The choice moved the game closer to being fun and balanced, something the textbook stresses is essential for a complete game.

Chapter 13 discusses stages of development, which we mostly ignored while developing Quack Attack. What I would change about our development process would be how we organise development time and make plans. We weren’t entirely without direction. People mostly followed the roles outlined in our part A, but we rarely ever set hard requirements and deadlines for what needed to be done, and didn’t differentiate between stages of development. Production development, such as feature implementation, happened simultaneously with QA work, such as playtesting. While early playtesting didn’t prove completely useless, that time would’ve likely been better spent completing the game’s features, and then playtesting that build for bugs and fun. The textbook also discusses the importance of making development plans that include a schedule. We definitely should’ve done this better by creating an internal schedule with deadlines for all our developers. Applying these concepts likely would’ve made development faster and resulted in a better game.

For the game's design, I would’ve liked to play more of a role in the initial conceptualising. The textbook talks about the importance of play testing early prototypes of games to ensure that systems and mechanics are fun before fully developing them. Since we weren’t starting our design from scratch, we ended up putting too much faith in the initial design without playtesting it. It wasn’t a bad design, and many of the core mechanics were fun, but some design choices (such as not being able to shoot while moving) were not fun and needed to be cut or changed. Had we discussed design more, or even made simple pen and paper prototypes early on, a lot of these issues could have been avoided in development.

Fullerton, T. (2018). Game Design Workshop: A Playcentric Approach to Creating Innovative Games. ProQuest Ebook. Retrieved from: https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/qut/reader.action?docID=5477698

0 notes

Text

A Few Examples of Change and Iteration in Assessment 3

As per our Assessment 3 part A, we have done playtesting of our Assessment 3 game, Quack Attack, throughout the development of the prototype. This was done so we could get constant feedback as we developed, and so that every feature is guaranteed to be fun and well implemented before we get further into development, making things easier to change. As a result, the game prototype has changed a modest amount.

Most of the feedback we looked for from our playtesters was on the fun and difficulty of the game. Our initial build that we playtested was too difficult, mainly because of the pink duck/healer duck. This is the enemy duck that heals enemy ducks around it, and in the original version, it healed too much and too often. As the player levelled their gun damage and fire rate, this became less of an issue, but the early game was much harder than we intended. As a result, we lowered the rate and amount of healing the pink duck did, and we also reduced its spawn rate by adding more ducks to spawn in its stead. This made it so the pink ducks only aided other ducks around them and did not make them borderline invincible.

On the issue of fun, the most common feedback was on our movement and shooting. In the original design, the player couldn’t move and fire their gun at the same time. The idea behind this was to make the gameplay more tactical and unique, forcing the player to move somewhere safe before firing their gun. Most playtesters remarked that this made the gameplay feel static and frustrating, and limited the player’s options, which was the opposite of our intent with the mechanic. Our original design did allow the player to spend a level-up point to unrestrict movement, but this was essentially just locking the game being fun behind a level-up, which playtesters said wasn’t good design. In our current build, we’ve removed this movement restriction and instead replaced the level-up option with a movement speed upgrade. This adds more depth to the gameplay and has been successful with our playtesters.

The final iteration I want to talk about isn’t related to playtesting and is something we always intended to do: iterate the art. I want to talk about this because I find it interesting, as it is something that is common in game development. Typically, games will have placeholder art so the developers see a rough version of what the final game will look like before the art is done. This is something we did in our game. One of our group members, when they first started building the game, made some quick art for the basic duck enemy, player character, and background. This can be seen in my last post, and it can also be seen that this was eventually changed. While the placeholder art wasn’t in the final game, it was invaluable for building and testing the game at the start of development.

0 notes

Text

Another Interesting Book Chapter

Chapter 11 of the Fullerton book, while being fairly short, discusses two very important topics in game design: fun and accessibility. I find the topics of this chapter very interesting because most of the book has talked about how to develop game mechanics and systems that are fun and how to consistently playtest them for fun, but this chapter talks about how designing multiple fun systems can still result in a game that isn’t fun.

This is because games are very unstable, and small changes/additions can result in a game losing its fun. The chapter discusses issues designers often find during development that dampen fun, such as micromanagement, insurmountable obstacles, arbitrary events, stagnation, and predictable paths. This is interesting because it showcases just how easy it is to introduce these problems to a game, and that they should be tested for at every stage of development, especially toward the end, to make sure your design is still fun.

Another important part of the chapter is accessibility. Making sure a game is fit for its target audience and easy and intuitive to play is very important. The chapter discusses how easy it is for a developer and their playtesters to become used to the designed controls and systems and become blind to any accessibility problems they may have. That is why it is important to test prototypes with outside participants who fit the target audience. This will ensure that the game will be easily accessible for most players.

Fullerton, T. (2018). Game Design Workshop: A Playcentric Approach to Creating Innovative Games. ProQuest Ebook. Retrieved from: https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/qut/reader.action?docID=5477698

0 notes

Text

Assessment 3 Playtesting

One of our main members spent some time Playtesting one of our first iterations of the game. While we still have a lot more to do, it was good to get early feedback on the core features of the game, and playtesting should be an iterative process that happens throughout all of development.

They found, initially, that the game was too hard, and some of the ducks need to be less powerful and the spawn rate needs to be lowered. We expected this, as we haven't done much internal playtesting, mostly just trying to build the features, and haven't fine-tuned all the balancing variables. However, we did spend the extra time trying to make most numbers represented with variables, making it very easy to make changes quickly to things damage, health, spawn rates, etc., as we playtest the game.

Based on this preliminary playtesting, we completed our prototype for Quack Attack and ran a final set of playtesting sessions. I ended up being the one in the group who ran most of these sessions, and since I’ve already written about the results extensively in the Assessment 3 playtesting report, in this post, I will mostly talk about the actual playtesting process.

I wanted to make the playtesting sessions as proper and professional as possible in order to get the best results and insights from playtesters (and also to get a good mark on assessment 3 :P). Following the guidelines from the lectures and chapter 9 of the Fullerton textbook, I began by finding playtesters who both played video games and were completely unfamiliar with our game. For each playtester, I would read them a script explaining the process for playtesting. I explained that for the first playtest, I can’t say anything about the game, but I will be writing down their insights, encouraging them to speak their thoughts out loud. For the second playtesting part, we will do deeper playtesting, where I can explain features and answer questions to test the experience as they become familiar with the game.

Before playing the game, the playtesters took a short questionnaire to gauge what demographics they fell into. Throughout the whole playtesting session, I was taking notes on what the player was doing and saying. During the deep playtesting, I would also ask the playtester questions about how they’re feeling about the game, how they like certain features, and if they need help with anything.

After each playtester finished playing the game, I took some time to discuss their feelings on the experience with them to allow them to collect their thoughts and opinions about the game. After that, I provided them with a short survey asking questions about how fun, difficult, buggy, etc., their experience was and what they thought about game elements like the enemies and art. The responses to this survey and my notes taken during playtesting formed the basis for the playtesting findings table and playtesting report in Assessment 3.

Fullerton, T. (2018). Game Design Workshop: A Playcentric Approach to Creating Innovative Games. ProQuest Ebook. Retrieved from: https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/qut/reader.action?docID=5477698

0 notes

Text

Assessment 3 Development Post

Over the past 2 weeks, we have made a decent amount of progress on the development of Quack Attack, our Asteroids-like duck game for Assessment 3. This is very ambitious and will require the full team working towards completing it. Fortunately, many of the steps outlined in the textbook, such as conceptualisation and prototyping, have already been done before we even formed our group, through one of our members' conceptualisation of the game for their Assessment 2 submission, and us creating Asteroids-like games in the tutorials. This means the bulk of our work will involve development and playtesting. This lengthy post, in particular, will detail the development process of the game and my personal commitments.

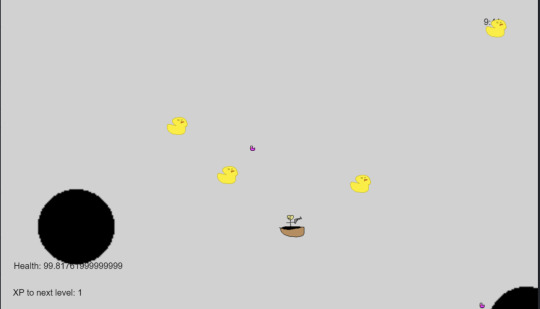

While I was working on other assignments, one of our team members got started building the base of the game. They added a lot of essential features, like the gun, upgrade system, duck spawning, health, etc. To start, this was using basic assets and animations, but it was functional very quickly. Seeing this, I quickly got to work adding more depth to the game based on our plans and one page.

Early, basic prototype

I started by adding new ducks. The first being the “pink duck” that heals nearby ducks. I made this work by spawning an invisible circle around the pink duck in 3-second intervals (this is subject to change) that heals all ducks that collide with it. I also added a healing indicator that pops up above all healed ducks, showing how much they got healed. I used this idea to add damage indicators as well, which appear every time a duck is shot by the player.

Pink duck's healing area of effect

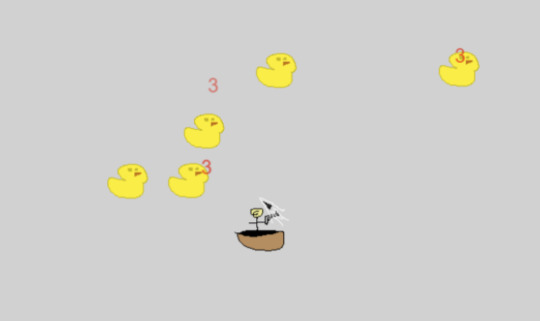

Damage indicators

Continuing, I added the “fire duck” that exploded when killed. It works like the regular duck, but when killed, it spawns the explosion animation texture provided by the tutors for the racing game, and destroys the ducks that collide with it. I also made it so that if the duck reaches the player, it spawns a bigger explosion, doing massive damage to the player.

At this point, a lot of the base features were coming together, but the game didn’t feel very good. To make the game feel more realistic and responsive, I added a slight knockback to all the ducks when they are hit by the player, and an even greater knockback when they hit the player. This makes the game feel much more responsive and acts as a cooldown from the ducks attacking the player.

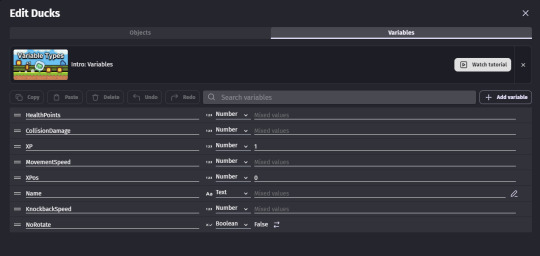

The game was coming together nicely, but more importantly, we had built a base on which to easily add new ducks and features. By creating a “Ducks” group in GDevelop, universal enemy variables, such as movement speed, health, damage, etc, can automatically be applied to all ducks. It also means that logic in the events tab that needs to apply to all ducks only requires one implementation, and it will apply to all duck types.

Variables that apply to all ducks

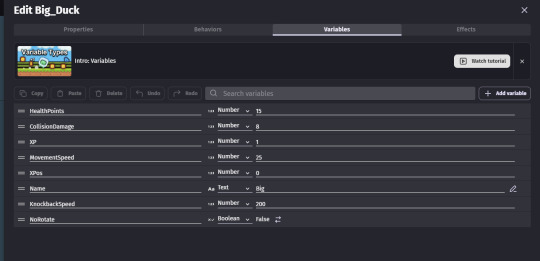

It also makes adding some new ducks trivial, such as the big duck, which is a larger duck that moves slowly, has high health, and does a lot of damage to the player. When adding this new duck type, all I had to do was adjust these variables accordingly, and the duck was fully functional. I did the same thing to add our boss duck, “The Trojan Duck”, making its movement speed slow, its health very high, and its damage also very high. The Trojan Duck will require more logic to fully meet our design doc, but that will be done by one of our other developers.

Big duck variable settings

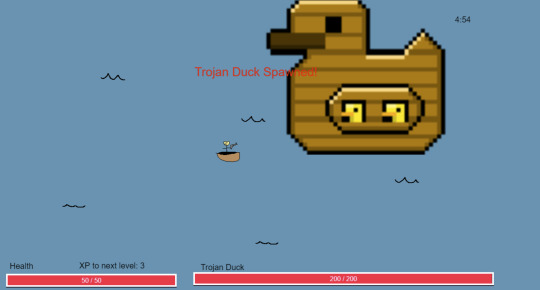

Trojan Duck boss

At this point, I added wave logic and boss spawning. Essentially, the game runs on a timer, having certain events at certain times, such as the new waves of duck spawning and boss spawning. This is done using scene timers, where once the scene timer hits a certain amount, it will trigger an event. This is all done with scene variables, making it easy to change how long the game lasts, when ducks and bosses spawn, etc., for balancing. I set it so that halfway through the main scene timer, a boss will spawn, and at the end of the timer, another will spawn. Using this, I added a win event, checking if the timer had reached zero and both boss ducks had been defeated in order for the player to win.

Boss spawn event, also demonstrates player and boss health bars

Finally, I added player health and boss health bars, using the built-in “resource bar” object in GDevelop. At this point, we had a new complete prototype for gameplay, allowing our other members to add sound effects/music and update the visuals.

Current version with updated visuals

During development, I mostly tried to incorporate theory from chapter 8 of the textbook, the chapter that covers digital prototyping. While a lot of aspects that the chapter covers, such as mechanics, viewpoints, and designing control schemes, were already designed before developing this prototype, some aspects had to be designed afterwards. The most notable aspect, discussed in the textbook, was effective user interface design. This section of the chapter talks about the importance of good UI design and how it needs to be clearly expressed to the player, easy to read, and contain all the important information for the player. We made sure to implement all these elements of UI, showing the player’s current XP requirements, health, and time left in the game. We also had to change the UI design of the level screen, since the levelling and upgrade system changed in the final version of the game. We made sure that all the options were clearly visible to the player, and what they did was obvious.

Application of Fullerton Textbook Theory

During development, I mostly tried to incorporate theory from chapter 8 of the textbook, the chapter that covers digital prototyping. While a lot of aspects that the chapter covers, such as mechanics, viewpoints, and designing control schemes, were already designed before developing this prototype, some aspects had to be designed afterwards. The most notable aspect, discussed in the textbook, was effective user interface design. This section of the chapter talks about the importance of good UI design and how it needs to be clearly expressed to the player, easy to read, and contain all the important information for the player. We made sure to implement all these elements of UI, showing the player’s current XP requirements, health, and time left in the game. We also had to change the UI design of the level screen, since the levelling and upgrade system changed in the final version of the game. We made sure that all the options were clearly visible to the player, and what they did was obvious.

Fullerton, T. (2018). Game Design Workshop: A Playcentric Approach to Creating Innovative Games. ProQuest Ebook. Retrieved from: https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/qut/reader.action?docID=5477698

0 notes

Text

Assessment 3 & Group Formation

Towards the tail end of my work on Assessment 2, I realised I should probably put some of my focus into finding a group for Assessment 3. I hadn’t attended the last workshop, and my next one was almost a week away, so I made a post in the “group formation” channel of the IGB Discord server. Even though it was late, I thankfully found two members who still needed a group and wanted to make a team. The following Monday, we were assigned a fourth member by the teaching staff and through week 10, we started having meetings and discussing plans.

For our first meeting, we all shared our one pages/sheets and began discussing whose game we wanted to develop for Assessment 3. While I was okay with developing my own, I would’ve preferred to do someone else’s, since I had already spent a long time working on it for Assessment 2 and wanted to work on something fresh. In the end, we decided on one of our group members’ game, “Quack Attack.” I liked this idea since it was also an Asteroids-style game and had some similar elements to mine, meaning I could carry some of my work over. However, it had a completely different style and had some different systems, like a levelling rather than a shopping system, more intense fights, and bosses.

Once we had agreed on a game, we started working on Assessment 3, part A, assigning roles, creating a timeline, and making some design changes to the game. My next post will outline Assessment 3 and the development of Quack Attack.

0 notes

Text

Racing Game Postmortem

For my racing game, Bad Tires, I employed the Fullerton textbook’s method of conceptualisation that’s detailed in Chapter 6. I knew for this game, I wanted to come up with a unique idea and develop it into a new game that’s never been done. To do that, I followed chapter 6 of the textbook, sitting down and having a brainstorming session. This allowed me to circulate different ideas through my head, imagining them, how they would be played, and if they were fun, until I landed on my idea for this racing game. I used that idea in my head to build the initial prototype and build off of it from there.

One thing that I wish I could change about development is the amount of time it took to actually develop the prototype in GDevelop. Chapter 10 of the textbook discusses the importance of functionality, completeness, and balance. I wanted to spend an ample amount of time on each of these pillars. However, making the base gameplay functional was very time-consuming and forced me to spend less time on completeness and balance. As a result, the game is less rounded than I would like it to be. I wish I had been required to spend so much time on functionality and/or had more time available to fully flesh out the game.

If I had to look back and change one thing about the design, I would want to add more stakes for the player. All the games I have developed in the tutorials have been “arcade” games, with no real goal other than to get a high score. This isn’t a bad player motivation, but I would’ve liked to make a game with something deeper. This would involve adding more dramatic elements and features to the game. For example, I could’ve made a level system where the player has to collect a certain amount of resources to complete a level, or arrive at a destination within a set time. This would give the player better motivation and a sense of progression as they complete levels. It would’ve required more scope in development, of course, but from a purely design perspective, it would’ve added more depth to the game.

Fullerton, T. (2018). Game Design Workshop: A Playcentric Approach to Creating Innovative Games. ProQuest Ebook. Retrieved from: https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/qut/reader.action?docID=5477698

0 notes

Text

Assessment 2 Discussion

Assessment 2 is thankfully in the books. This assessment actually ended up being a lot harder than I expected. There were a lot of requirements, and a lot of thinking ahead and planning was necessary to come up with a good result. I am happy with the final result, though, so in this post I will discuss assessment 2, my process in making my one page and one sheet, and how I feel about the results.

After reading through the assignment descriptions, I spent a day brainstorming ideas for the game I wanted to document. I initially wanted to create something different from the prototypes I designed in the tutorials. I devised this idea for a jungle time-based platformer, where the platforms slowly crumble and fall, forcing the player to keep moving. I had different obstacles and platforms, but in the end, I scrapped this idea. I tried creating an image of the game in Photoshop, but it didn’t turn out very well, and I knew it would be best to try to make it into a prototype in GDevelop, which I didn’t have time to do.

First game idea concept art

In the end, I used one of my old tutorial prototypes, specifically the Asteroids game. This was because I already had a substantial prototype built in GDevelop. I decided to build my idea of an Asteroid game with a shop, upgrades, and new abilities to fruition for Assessment 2.

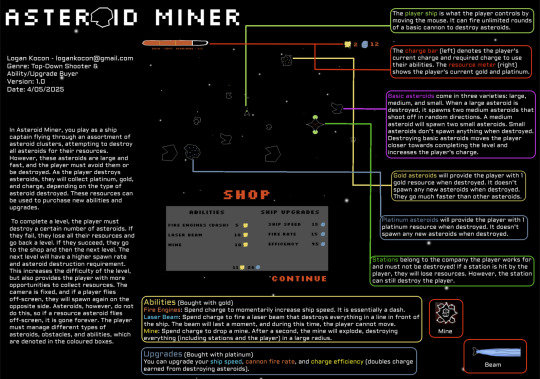

First, I wrote up the description/elevator pitch for the one page. Once that was done, I used that work to continue the GDevelop prototype. I added new asteroid types, the station object, and an updated charge meter, which were all playable features. I created a “shop” scene with all the purchasable upgrades and abilities. This, however, was just for a screenshot on the one page and didn’t have any functionality.

I compiled all the screenshots on a one page, wrote descriptions for all the objects and features, and added some flair, with highlights and different colored texts. It took a lot of trial and error to make a layout for the one page that was easy to follow, detailed and descriptive, and had extra room to add onto later.

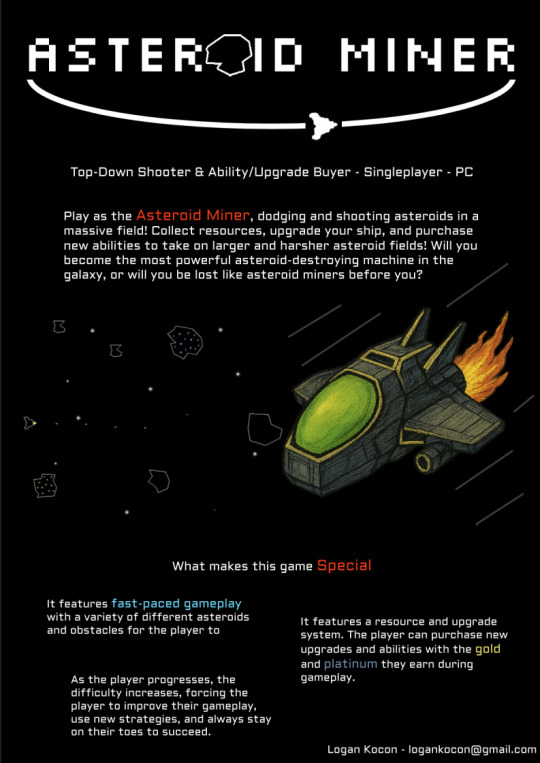

The one sheet was a lot easier. I took the time to make a custom logo for “Asteroid Miner”, added the required text (elevator pitch, three unique selling points) and finally made some custom art with Chat GPT. I usually don’t like using AI art, but I figured it was justified considering I was a terrible artist. If this were a real game, I wouldn’t use AI art.

Overall, the project came together nicely. The one page and one sheet are informative and stylised enough for me to be satisfied with my work. I also think the game I came up with seems really fun, and has a lot of unique ideas, like the “station” that costs the player resources if destroyed. I also really like the dramatic aspect of the game, where the player needs to fight through an asteroid field with sudden death around every corner as a job. It’s just to make a living. It’s interesting to try putting yourself into the shoes of people who may live hundreds of years in the future.

Final one page

Final one sheet

0 notes

Text

Racer Development Post

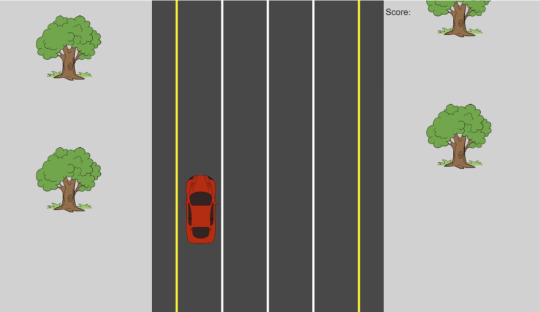

Let’s talk about the development of Bad Tires. Like all my other games, I started by following the tutorial slides as a basis for my racer game. Following the tutorials got me some basic player car movement (that I would later completely overhaul), spawning cars, collision, moving trees, and a myriad of useful assets. This served as a great basis for the start of my development.

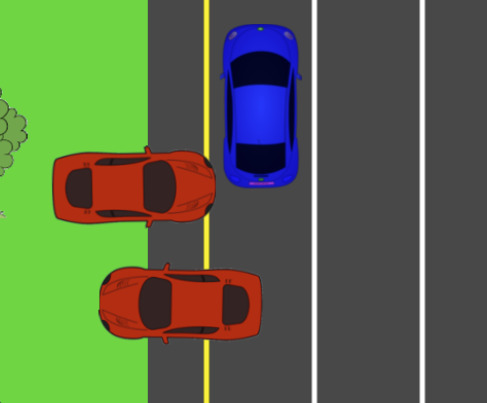

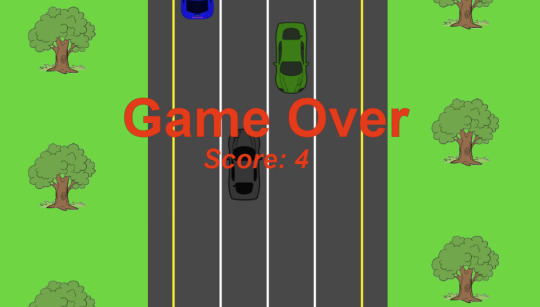

Basic version of the game at this point.

The first thing I wanted to do was develop the movement of my car to match the movement described in the elevator pitch. The basic idea was to not allow the player to directly move left or right, but to only allow the player to rotate. However, the player can change the axis point by which the car rotates, either from the top or the bottom. Switching between these axes will actually allow the player to move the car.

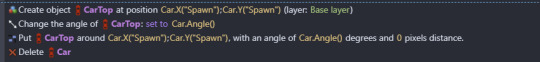

This was surprisingly difficult to implement. I originally thought it would be as simple as adding different “points” on the car sprite and changing which point the car rotates around depending on user input. However, I quickly learned that GDevelop doesn’t support this; in fact, you can only rotate around the centre point. Fortunately, you can change the centre point, but only through the engine (this can’t be changed during runtime as an action). My solution to this was to create a separate car object with a different centre point and simply switch the objects whenever the player wants to switch their axis of rotation. Again, not so simple. Spawning this new car at the same position with the same angle didn't put it in the same spot.

Offset positioning of the cars

This is because, since the new object had a different axis of rotation, when I would rotate it to match the angle of the original car, it would rotate around a different point, thus changing its position relative to the other car. This was incredibly annoying. I tried using math to adjust the new car’s position to line up with the old car, but couldn’t get it right since the amount of offset would change based on the angle. Finally, through sheer will, I figured out that using the “put around” action and matching a “spawn” point on the original car with the origin point of the new car would line them up perfectly when I set the angle of the new car.

Actions to swap cars

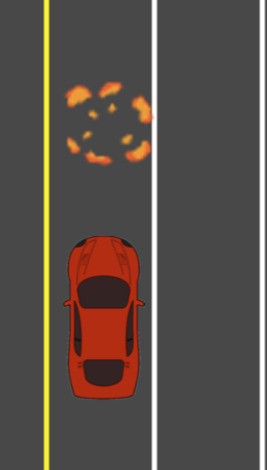

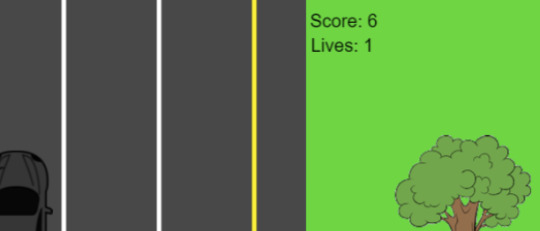

Once I got the switching between cars logic working, all I had to do was set the rotation for each car, and the movement was complete. I allow the player to rotate a full 90 degrees, giving more freedom of movement. The result of all of this was a really dumb and hard game. It reminds me of QWOP, with its wacky and frustrating controls. But, like QWOP, I find it quite fun. Getting used to the movement and finding ways to make the car easier to control is part of the fun. But I still thought it was too hard, so I lowered the spawn rate of the cars (made them spawn every 4-6 seconds) and implemented a lives system. If a player touches a car but still has remaining lives, the player loses a life, and the car they hit is destroyed with a smaller version of the explosion animation spawned.

Collision with car

Due to the difficulty in implementing the movement, I didn’t have time to create different textures for the car based on the number of lives like I wanted, so I just displayed it in the corner next to the score.

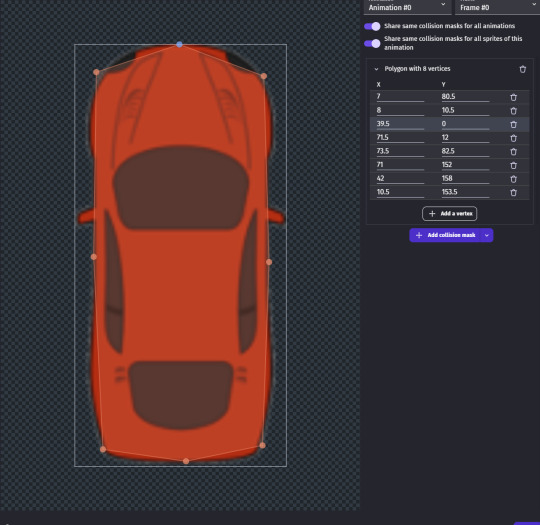

Because the car has such precise movements, it should be able to get really close to the other cars without touching them. The default collision mask, however, was too wide for this, resulting in the player often losing a life from a car they didn’t even touch. Because of this, I went through all the car sprites and added a custom collision mask to make it fairer for the player.

Example of updated collision mesh

At this point, I was almost done. I put the two player cars into a new “CarGroup” so I don’t have to take into account both cars, I can just use the car group for things like detecting collision with traffic. Finally, I implemented a simple game over screen that lasts 3 seconds before restarting, and made the background green to give the trees some grass to grow on.

I like how this game turned out. It’s frustratingly weird, but it’s fun playing around with it and trying to learn and get better at its mechanics. I could definitely use some more playtesting to really fine-tune it, but for now, I think it’s really fun!

Application of Fullerton Textbook Theory

In my Asteroids postmortem, I discussed wanting to develop multiple unique systems that come together to create a well-rounded game. That didn’t really happen, but I’m still happy with my development as a whole. My primary focus for this prototype, like my platformer, was kinesthetics, making the game feel good. Overall, I developed a technical prototype for a racing game with a unique control scheme. As discussed above, since this control scheme was so unique, it was tough to build in GDevelop. Fortunately, I was able to get the system working and playtest it. While chapter 8 of the textbook talks about the importance of many elements in digital prototyping, kinesthetics is the one I wanted to focus on the most. Kinesthetics is how the game feels, which is vital because game-feel is ubiquitous in the game, influencing almost every aspect of it. If the game doesn’t feel fun to play, it is not fun.

This book chapter also discusses developing original systems and control for digital prototypes. This is something that can be prototyped and tested non-digitally, but digital prototypes give the best representation of how the systems will feel in a game. Originality is important because it allows a game to stand out, giving players reason to play it over others. While I tried to be original with my other games, I felt like this game turned out to be the most unique. So much so that I found it difficult to gauge whether it would be fun before actually developing it in GDevelop. Thankfully, now that the prototype is built, I think the idea is fun and would make for a good web/flash game.

Fullerton, T. (2018). Game Design Workshop: A Playcentric Approach to Creating Innovative Games. ProQuest Ebook. Retrieved from: https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/qut/reader.action?docID=5477698

Other assets retrieved from IGB120 Workshop 7 https://canvas.qut.edu.au/courses/21200/pages/igb120-w7-workshop-racer?module_item_id=1941908

0 notes

Text

Racer Elevator Pitch

Gameplay

For my third and final tutorial game, I will be creating Bad Tires. In Bad Tires, the player must navigate through multiple lanes of traffic, avoiding cars in the ongoing and incoming traffic lanes. For each car the player successfully avoids, they will receive a single point. However, as the title may suggest, driving the player’s car isn’t as simple as one may assume. Rather than simply moving left and right, the car can only be driven by either turning the back tires or front tires while braking the opposite set of tires. As a result, movement is done by rotating the car around the front or back as the axis. This creates a dynamic and unique movement system with, what I imagine, will be a tough learning curve. As a result, I plan to make the positioning of the cars more random, but less forgiving than the in-class demo version of the game. I will also create a lives system denoted by visual damage to the car.

Why It’s Compelling

This game, like the others, features an arcade-like gameplay loop, meaning the player's objective is to survive as long as possible, thereby earning the highest score possible. The unique movement system offers players a racing game that is dissimilar from anything they’ve played before, and ideally, the desire to conquer this unique system will be a good motivator to play. I also think that because driving is so unique, most players will be very bad at controlling it at first, making their progress much more rewarding. I think striking a balance between difficult and frustrating with the driving mechanic will be essential while building the prototype.

Setting

In Bad Tires, you play as Brad Tylers, a businessman late for an important meeting. You drive your poorly-maintained car as fast as possible down the highway of an Australian city and through ongoing traffic to make it to your meeting. Too bad it’s so far away.

Target Audience

Anyone looking for a challenge in a game.

Elevator Pitch For Bad Tires

In Bad Tires, you play as Brad Tylers, a businessman running late for an important meeting. While Brad does have a good understanding of driving safely, he unfortunately must drive exceedingly over the speed limit into oncoming traffic in his… less than ideal vehicle. He’s late for work–what is he supposed to do? Players must control Brad, steering his vehicle, making wide turns, and spinning through traffic, in an attempt to avoid colliding with the other cars on the road. The longer you can keep Brad alive, the higher your score. He never seems to actually make it to work, though.

0 notes

Text

Asteroids Game Postmortem

One thing I really wanted to incorporate from the Fullerton readings in the design of my Asteroids game was the concept of multiple systems working together to create a cohesive experience. The platformer I designed mostly revolved around a single system, the movement of the player. Sure, there were platforms and enemies to avoid, but these objects were fairly static and didn’t provide much other than a tool for the player's movement. However, an Asteroids game can be much more complex, allowing for systems to be designed to work well with other systems. For example, when a larger asteroid is destroyed, it spawns multiple smaller asteroids, making asteroids often “bunch up.” This is why I implemented the mine, since it would allow the player to quickly destroy a lot of asteroids when they are grouped together. However, the player would have to time it properly, due to the mine’s time to detonate, adding more strategy and depth to the system. This is a good example of multiple complex systems working well together in my game.

One thing the book talks about is prototyping different new and unique systems and mechanics. A good example mentioned in the book is Katamari Damacy, a game made up of a completely unique mechanic (rolling a ball around, picking stuff up), that started as one developer playing around with a prototype. I think this is something I should aim to do with my prototypes, and something I didn’t really do with Asteroid Miner. Sure, I played around with different systems and how they interact with each other, but I didn’t make those systems unique. Dash, mine, and laser beam abilities are easy to develop and don’t provide the player with a unique experience. For my next game, I want to try to be more creative, making multiple interesting and unfamiliar systems that also blend together well. I want to, essentially, combine what I believe I did well in my platformer game with what I did well in my asteroids game. We will see how that goes.

Fullerton, T. (2018). Game Design Workshop: A Playcentric Approach to Creating Innovative Games. ProQuest Ebook. Retrieved from: https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/qut/reader.action?docID=5477698

0 notes

Text

Reflecting on Chapter 5 of the Textbook

Let’s take a quick break from discussing GDevelop and the games I’m creating, and go on a small tangent. Chapter 5 of the Fullerton textbook dives into game systems, their elements, and how they interact with each other, which I found quite interesting, so I’ll talk about it here real quick.

The entire textbook, but this chapter in particular, seems to attempt to quantify and deconstruct game systems and how a game functions. I’ve always found those sorts of things interesting, since game design is something we instinctively understand through our experiences playing games. We understand that games have different objects and systems that interact with each other. We understand, in an abstract manner, how these elements come together to make a game. And, most importantly, we understand when a game is or isn’t fun.

What I find interesting here is how the chapter quantifies these things. It explains that, yes, a game has objects that have specific properties and follow specific rules, and have certain abilities, and must be controlled by the player in a certain way. The chapter explains why games may be considered unfun. For example, if a game is unbalanced, meaning certain players have unfair advantages, it hurts the fun factor of the experience. Players would feel that when playing an unbalanced game, but be unsure why.

Being able to deconstruct games and understand elements like objects, properties, controls, feedback, etc in more than just the abstract way you would understand them by only playing games, allows game designers to be quicker in their design process, understand the game their designing entirely, be able to know what individual parts need tweaking based on playtesting and feedback, and communicate their design and vision easier. This makes the content of chapter 5 and the entire textbook invaluable to a game designer.

Fullerton, T. (2018). Game Design Workshop: A Playcentric Approach to Creating Innovative Games. ProQuest Ebook. Retrieved from: https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/qut/reader.action?docID=5477698

0 notes

Text

Asteroids Game Showcase Video #2

Showcase of the game over screen.

0 notes

Text

Asteroids Game Showcase Video #1

Showcase of the mine and explosion ability. Yes, my explosion texture is really bad.

0 notes

Text

Asteroids Development Post

Looking back on my original elevator pitch for this Asteroids game, I didn’t realise how much would be required to develop the simple Asteroids-style mechanics and the extra abilities for the player. This post will detail the process I went through and the final outcome for my rendition of Asteroids.

Similar to the platformer, my basis for developing this game was to follow the tutorial slides, creating a simple but functional game. After the tutorial, I had functioning ship movement (following the mouse cursor), a working gun that fires bullets in a set interval, a system for spawning large asteroids with a random texture (from a set of 3), and a simple game over screen.

The first thing I developed on my own was the firing engines mechanic (dash). This was trivial, as all I needed to do was add a large force for about a second when the “shift” key was pressed, then set the motion of the object to zero, resetting movement after the dash. However, I wanted the number of possible dashes to be limited, so I added a new “Charge” variable that incremented for every asteroid destroyed and was spent to use special abilities. At first, I set the cost to 5 “charge” but decided 10 was more balanced after some testing. I also decided I wanted a visible fire coming out of the back of the ship while it was dashing, and the given triangular ship texture was too simple. I created a new ship texture and a variant with fire coming out of the ship.

Player ship texture

Next, I wanted to add more variety to the asteroids, similar to the original game. I made it so that when an asteroid is destroyed, two smaller asteroids spawn, flying in random directions. To do this, I added a medium asteroid and a small asteroid object, and spawned them with a force towards a random angle when a larger asteroid was destroyed. No asteroids are spawned when a small asteroid is destroyed. They also spawn with a random texture, giving more variety.

Broken asteroid

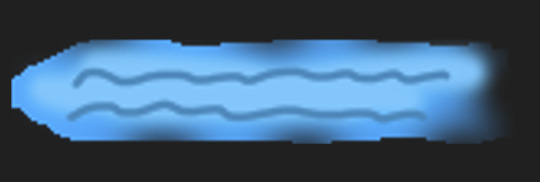

To add the beam weapon ability, I created a custom beam texture that would temporarily spawn in front of the player when “1” was pressed on the keyboard. After the beam sprite is spawned, I also stop the player, making it so that the position of the beam is fixed and giving a moment of vulnerability to the player every time it is fired (this is a design choice). I also have to rotate the beam to match the angle the ship is facing. To create the mine ability, I created two more custom textures: a mine texture and a (really bad) explosion texture. When the player presses the “2” key, it spawns a mine object at that position that will, after a few seconds, spawn an explosion object, which is much bigger and destroys anything it collides with (player included). Finally, I set a required charge cost for both abilities and subtracted that amount from the charge when they are used.

Mine texture

Beam texture

For balancing the ability costs, I found that the dash costing 10 charge felt like a good balance, and I knew I wanted the other abilities to cost more than the dash. At first, I tried having the beam cost 20 and the explosion cost 30, which felt like a good cost for the beam ability only. Because of the delay between dropping the mine and the explosion, and the fact that it can also kill the player, the mine was much less effective than I imagined it would be. To fix this, I brought the mine’s price down to 20, same as the beam. This made the game feel more balanced and had the extra bonus of the player having to know fewer numbers.

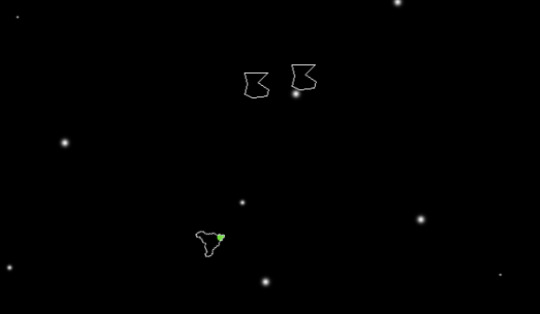

One final thing I did, mostly because I just couldn’t get the idea out of my head, was to update the game over screen, making it a view of space with destroyed ship pieces floating about. I created three new textures made from different parts of the ship texture, and added them as three new objects in the game over screen. I added an event that, at the start of the game over scene, created these three new objects and gave them a light force drifting away from each other. Finally, I moved the “game over” text and displayed the score.

Game over screen

Now, I never actually added any shop or roguelike mechanics that I outlined in the elevator pitch. I should probably stop saying I’m going to do that. Truthfully, I didn’t actually think I would have the time to implement any of this, but it sounded like a really cool idea for a game, and if I did have time, I would’ve, so I included it in the elevator pitch. I’m not sure this is the right approach, but it’s what I did. For the next game, now that I’m equipped with much more knowledge of game development and GDevelop, I will create an elevator pitch based on what I think is fun AND what I can implement in a relatively short amount of time.

Basic gameplay video

More gameplay videos can be found in the posts above.

Application of Fullerton Textbook Theory

While a focus for this game was fun, I wanted to put more emphasis on practising designing and developing more complex game systems and rules. Chapter 3 of the textbook discusses formal elements of games such as objectives, procedures, and rules. I wanted to include all these elements during development, something I didn’t successfully do in my last prototype. The game's main objective is to achieve a high score by destroying asteroids, and the procedures involve flying around, destroying asteroids and using special abilities. These abilities are governed by rules, requiring the player to have a certain amount of resources (charge). As stated above, I playtested the game a lot to fine-tune these rules and ensure that each ability had a fair charge requirement.

My platformer seemed to be more like a prototype than a complete game. While I understand this is still mostly a prototype, I wanted to start practising what it takes to make a well-rounded game. Including and playtesting the formal elements mentioned above achieves this, making them essential to include in this game.

Fullerton, T. (2018). Game Design Workshop: A Playcentric Approach to Creating Innovative Games. ProQuest Ebook. Retrieved from: https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/qut/reader.action?docID=5477698

Other assets retrieved from IGB120 Workshop 5 https://canvas.qut.edu.au/courses/21200/pages/igb120-w5-workshop-asteroids?module_item_id=1936019

0 notes

Text

Asteroids Game Elevator Pitch

Gameplay

Asteroid Miner features gameplay very similar to Asteroids. Rather than trying to reinvent the gameplay of Asteroids entirely, I decided to keep the core gameplay mechanics and build off of them. The player can move their ship around from a top-down view and fire a weapon while avoiding Asteroids. However, they also have other abilities, such as firing their engine (essentially a dash move), firing a laser beam that destroys all asteroids in a line in front of the player, and a mine that will destroy all asteroids in a certain radius after dropping. The player can only use these abilities after building up a “charge” by destroying asteroids. Unlikely my previous game, I think Asteroid Miner may be better suited to a rogue-like gameplay style, where the player can purchase upgrades and further abilities. However, once again, developing this feature may prove difficult with the limited time allocated to this project.

Why It Is Compelling

I think this idea is compelling because, at its core, it has the same gameplay as Asteroids but with a twist. Adding new features and abilities for the player to use gives them more options for gameplay and more unique tactics they can use to win. Using their abilities effectively will reward the player with more charges to use their abilities again sooner, meaning a skilled player can quickly destroy multiple asteroids with a completely different strategy to regular Asteroids, while still having that simple Asteroids gameplay at its core.

Setting

You are the captain of a spaceship that works for some company to destroy asteroids for their natural resources. Your goal is to fly through an asteroid belt, destroying as many asteroids as you can to earn as much money as you can. This concept also serves well to that rogue-like idea.

Target Audience

Anyone interested in arcade-like Asteroids-style games.

Elevator Pitch for Asteroid Miner

In Asteroid Miner, you control a small ship flying through an asteroid belt, looking to destroy as many asteroids as possible, collecting their resources for money. However, the job is dangerous, as your ship has seen better days, and a collision with an intact asteroid could completely destroy it! To succeed, the player must navigate the asteroid belt, destroying as many asteroids as possible with their main gun while also avoiding coming into contact with one. Destroying asteroids can also build up your ship’s “charge”, allowing it to fire its engines and use more powerful weapons. In between rounds, the player can use their earnings from destroying asteroids to purchase different upgrades and more powerful abilities to fight through more dangerous asteroid belts!

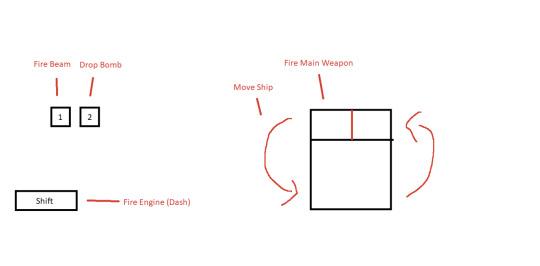

Controls Diagram

0 notes

Text

Platformer Postmortem

The main part of the Fullerton readings that inspired my design was the earliest introduced and probably most important aspect of the book, the player-centric approach. This was reflected in my early concept for a rogue-like platforming game. While I still think this was an interesting idea and would have been fun to develop, with the time I have for this particular project, I don’t think I could have made it fun. And that is the most important thing. The idea of iterating your game to make it as fun as possible from the textbook is an idea I used throughout every step of this project. Throughout the initial design and development of the base features, I tried to make everything as fun as possible, and continuously iterated, especially at the end, making big and small changes.

While I do like how the prototype turned out, I would’ve liked to flesh it out more. This would include adding a more advanced scoring system, expanding the level, adding more levels, and adding more enemies. Fleshing out different systems and giving the player clearer goals will reinforce the gameplay loop and give the player more motivation to play the game. I would’ve also liked to make the movement feel more responsive. I could accomplish this by adding more animations, continuing to tweak the movement to make it feel better, and adding effects based on the player’s actions. This would make for better kinesthetics and a more fun experience.

For my design, I would’ve liked to consider more than just the movement of the character. The book talks about prototyping individual features, but to create a fun, engaging and complete game, a developer must combine multiple unique and well-thought-out prototypes. My current game serves as a prototype of a single feature, the movement of the player character. And while this is fine, in future prototypes, I need to start considering all aspects of a game and how to make them fun, as this will be important for creating well-rounded games in future assessments.

Fullerton, T. (2018). Game Design Workshop: A Playcentric Approach to Creating Innovative Games. ProQuest Ebook. Retrieved from: https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/qut/reader.action?docID=5477698

0 notes