Text

Aristocratic Adolescence

Lucile Desmoulins was no fool.[1] Her journal entries, albeit often a romantic exploration into the life of an aristocratic teenager in pre-revolutionary France, detail that Lucile was widely read and well educated for a woman of her time.[2] Although many of her musings were directly related to the ideas of her favourite scholars (Rousseau), they also show an independent and critical voice on issues of the day, particularly social class.[3] A specific entry dated 7-9 July 1788, however, details the impatience of Lucile, like many teenagers irrespective of time, for her life to start.[4]

Custom activities for girls coming of age in the Ancien Regime included accompanying their mothers to social events and learning the domestic tasks that they would one day perform for their husbands.[5] As we can see, Lucile’s education clashed violently with society’s expectations of her; her daily routine of badminton, social calls and singing was met with a feeling of “melancholy”.[6]

232 years since this diary entry was written, many of Lucile’s inner thoughts are still transcribable and valid to teenage girls today. “Good Lord, how boring this is,” is a testament to those on the brink of adulthood: Lucile’s captivation with the writings of the philosophes is reflected by contemporary teens alignment of adolescent expectations with dramatized tv shows and movies.[7]

Retrospect offers us the knowledge that within just over a year, Lucile’s life would be forever changed by the Storming of the Bastille. Perhaps for teenagers today, that turning point is represented by a global pandemic or the murder of George Floyd.

[1] Violet Methley, Camille Desmoulins; A Biography (London: Martin Secker, 1914), 41.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Diary of Lucile Duplessis 7-9 July 1788, found within Philippe Lejeune, On Diary (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2009), 91.

[5] Margaret H. Darrow, “French Noblewomen and the New Domesticity, 1750-1850,” Feminist Studies, vol. 5, no. 1 (1979): 52.

[6] Diary of Lucile Duplessis 7-9 July 1788, found within Philippe Lejeune, On Diary (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2009), 91.

[7] Diary 7-9 July 1788, Lejeune, On Diary, 91.

3 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Is it really true that you love me? You love me ..... You love Lucile ...... Well, if you love me, flee from me, I am a monster

Lucile Duplessis’ diary, July 16 1790

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Education, Feminism and Rousseau

The Age the Enlightenment engulfed Europe in the 16th Century, Jean-Jacques Rousseau a very influential contributor. The ideas discussed in Rousseau’s most popular works, Emile and The Social Contract, were extrapolated and used as guiding theory for French Revolutionists. What we learn from her journal, is that for Lucile Desmoulins, Rousseau played a pivotal role in formulating her conception and understanding of the changing world around her.[1] This insight allows for a more detailed construction of who Lucile was.

An issue which was often an oversight of philosophical enquiry was the relationship between women and the State.[2] Conversely, Rousseau used the rationality of reason to elucidate that in spite of the challenging of social conventions, the patriarchal relationship between men and women should remain the same.[3] The confinement of women to the domestic and private space was essential for Rousseau’s theory, as it would enable men to change the public sphere in which the social inequalities that he was interested in were found.[4]

So where did this leave Lucile? The condemnation of educated women like herself by her literary hero seems to have eluded her; rather she focused on his critiques of the social structures around her and continued her idolization. Curiously, Rousseau’s conceptions of gender equality may have permeated Lucile’s consciousness, revealing themselves later in life: her marriage to Camille was to become the center of her world and her short adult life would be largely relegated to the domestic roles of wife and mother.

[1] Methley, Camille Desmoulins, 41.

[2] Linda Kerber, “The Republican Mother: Women and the Enlightenment – An American Perspective,” American Quarterly, vol. 28, no. 2 (1976): 189.

[3] Kerber, “The Republican Mother,” 203 and Jane Abray, “Feminism in the French Revolution,” The American Historical Review, vol. 80, no. 1 (1975): 45.

[4] Kerber, “The Republican Mother,” 203.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Fall (or Call) of the Bastille

The Fall of the Bastille for Lucile was significant for two reasons: the symbolic end of tyranny and Camille’s persuasion of her father for her hand in marriage.

The Fall of the Bastille was the result of months of building tensions between the leaders of the Ancien Regime and the members of the Third Estate. The Parisian jail held only 7 prisoners at the time of its destruction, however the concrete structure was symbolic of monarchical absolutism.[1] As the first significant act of popular sovereignty, the attack on the Bastille was aggravated by an intense feeling of insecurity within Paris: members of the Third Estate for the first time in their lives were beginning to question the benevolence of their King and their acceptance of the ruling elite.[2] The instigators of this revolutionary event used the language of the people to inspire agency and set a discursive path for the remainder of the revolution.[3]

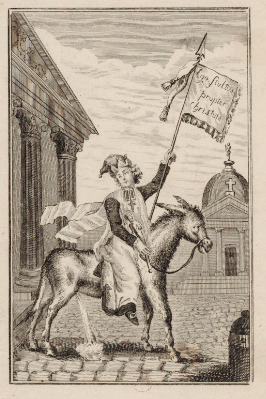

One such instigator was our very own Camille Desmoulins, who until this moment had been a stuttering lawyer with a head full of ideas, and not nearly enough money or social standing to impress Lucile’s father Claude-Etienne Laridon-Duplessis. Standing on a table at the Café de Foy, Camille’s stutter disappeared as he called for the Storming of the Bastille; radicalizing the public as participants of their own revolution.[4] This established Camille’s career as a politician and political journalist, and won the favour of Monsieur Duplessis.[5]

The Fall of the Bastille had cataclysmic repercussion for the course of the French Revolution, but also directly for the future and life of Lucile Desmoulins. Marrying Camille threw Lucile into the front line of politics and society; a front line which she would later die on. Events during the French Revolution, and events in our contemporary world today, are depicted as creating mammoth consequences for the outcome of society. Nonetheless, through Lucile it is clear that these events have very personalized outcomes for individual people.

[1] Methley, Camille Desmoulins, 69.

[2] William H. Sewell, “Historical events as transformations of structure: Inventing revolution at the Bastille,” Theory and Society, vol. 25, no. 6 (1996): 849.

[3] Ibid, 848.

[4] Hans-Jurgen Lusebrink and Rolf Reichardt, The Bastille: A History of a Symbol of Despotism and Freedom, (Durham: Duke University Press, 1997): 45.

[5] Methley, Camille Desmoulins, 63.

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Event of the Year

The wedding of Camille and Lucile on Christmas Eve 1790 was reminiscent of a modern day celebrity palooza.[1] As the daughter of a wealthy Parisian family and the new found orator of the revolution tied the knot, their guest list, chosen witnesses and decisions regarding religion were all elements worthy of a gossip column, or double page spread in a magazine. Their guest list included the notable Parisian revolutionaries of the time: Sillery, Mercier, Jerome Petion and Brissot de Warville.[2] Nevertheless, they were all stood up by the attendance of Maximilian de Robespierre: not only best friend of the groom, but also the signatory witness of the union.[3]

The wedding was also a political talking point; religion was a discursive focus for France at the time, this particular event occurring in the midst of the double pronged approach to reform the Church, known as the Civil Constitution of the Clergy.

Thus, Robespierre and Camille’s attendance and participation to such an event was a political statement. Since the Enlightenment and publishing of the encyclopedie, there had been fervent calls to disband the Clergy and all of the exploitative despotism which accompanied it.[4] Like Lucile, Camille and Robespierre had likened to the works of Rousseau, who had moderate ideas for religious reform in comparison to many of his intellectual peers.[5] Therefore, at the request of Lucile’s traditionalist parents, a religious wedding took place.

Unfortunately for him, Camille was not in high favour with the Church due to some outspoken criticism of Clergy behaviour published within his newspaper. At the mercy of the Curé of St. Sulpice, Camille was required to compose a public profession of his Catholic faith and both he and Lucile were to attend a confession.[6] Whilst they did indeed both attend a Catholic confession, Camille never did complete a public admittance of Catholicism, remaining true to his word of never proclaiming something he didn’t believe in.[7]

And so they did wed, Lucile in a pink satin gown and silk garter embroidered with forget-me-nots and the words Unisson-nous-pour-la-vie.[8] It turned out to be a very emotional event. Dictated to his father, Camille would write that he and Lucile both wept, with many guests also shedding a tear at various durations throughout the ceremony.[9] Lucile’s future was never to be boring again: her marriage to Camille meant that she was privy to some of the most important, private conversations between members of the Cordeliers Club, and later the National Assembly, and later still the Dantonists. Faithfully, she would remain Camille’s biggest support and sounding board for Camille’s most radical ideas and publications. Evidently, the emotion showed within this wedding demonstrates that Lucile’s devotion to the revolutionary cause was deeply intertwined with her devotion to her husband.

[1] Methley, 125-127.

[2] Ibid, 128.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Charles A. Gliozzo, “The Philosophes and Religion: Intellectual Origins of the Dechristianization Movement in the French Revolution,” Church History, vol. 40, no. 3 (1971): 273.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Methley, Camille Desmoulins, 126.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid, 128.

[9] Camille to Jean Benoît Nicolas Desmoulins, 24 December 1790, found within Violet Methley, Camille Desmoulins; A Biography (London: Martin Secker, 1914), 127.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Parisian Cafes

During the early years of the Revolution, the Cafés in the heart of Paris were used as spaces to develop democratic discourse and participatory democracy.[1] From a letter that Camille wrote to his father in 1789, the Cafés were described as, “astonishing spectacles”, full of controversial reading material and the thinkers of the moment.[2] As we’ve previously discussed, the Café de Foy was where Camille would call for the Storming of the Bastille and begin his life of politics.

Revolutionary politics was a male dominated space, so it would make sense that most patrons were men. Women from working class families were not frequently seen participating in this social crowd; the logistics of going to a café to spend money on food and drink, finding someone to watch the children, and finding time in the day outside of their domestic labour often made it near impossible.[3]

However, Lucile Desmoulins was not working class and cafés were the primary circuit for all Parisian social networks.[4] Lucile’s journal contains references to the Café des Ecoles, a popular café for the Cordeliers Club that was owned by her friend Gabrielle Danton’s parents.[5] Although this reference only tells of Lucile sitting in at the café to hear the news during a time of crisis (The Attack on the Tuileries), Lucile and Camille’s habits of entertaining and mischief leads to an assumption that Lucile would have enjoyed spending time out in society at the cafés, if only to allow others to admire her well-known beauty.[6]

The geographical closeness of Paris entailed that the apartment Lucile and Camille shared on the Rue de Conde (coincidentally the same building as the Danton’s), was a short walk from many surrounding cafes. This closeness of revolutionary ideas being discussed over café tables, at dinner parties, and in tennis courts, fabricated a stifling intensity within Paris; Lucile and other Parisians were known to often take leaves of absences from their celebrity spotlight and flee to their country houses for spells of quietness.[7] So whilst café’s initially provided a space for democratic discourse, it is evident that the Revolution soon became all-consuming and invading, distracting from ordinary boundaries of

[1] W. Scott Haine, The World of the Paris Café: Sociability Among the French Working Class, 1789-1914 (Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 1998), 210.

[2] Letter from Camille Desmoulins to his father 1789, found within Hain, The World of the Paris Café, 210.

[3] Hain, The World of the Paris Café, 203.

[4] Ibid, 2.

[5] Methley, Camille Desmoulins, 188.

[6] Ibid, 188 and 122.

[7] Ibid, 212.

0 notes

Quote

May I remind Monsieur Camille Desmoulins that neither the beautiful eyes nor the beautiful attributes of charming Lucile are reasons for not announcing my work on the National Guard, which was presented to him, and I have sent him a copy if necessary. There is not at this time anything more urgent or important than the organization of the National Guard ..... I pray Camille not to loose it....

Letter from Robespierre to Desmoulins, 1792

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Private Courage

Lucile’s account of the 9th- 11th of August 1792 is one of her longest and most insightful journal entries. Covering the events which have come to be known as the Attack on the Tuileries, Lucile takes readers inside her apartment and the terror which she and the other women felt as they waited for their husbands to return from the violent revolutionary journée.

The Attack on the Tuileries, like many other Revolutionary events, was triggered by a culmination of factors, exacerbated by dichotomous opinions over the fate of the Monarchy. King Louis and Marie-Antoinette’s Flight to Varennes in June 1791 had exposed the Monarchy as traitors for many Parisians, and this in addition to the Civil Constitution of the Clergy, had developed a subculture of Counter Revolutionaries, and moderate factions (Girondins) within the Assembly. The Declaration of War against Austria in 1792 added fuel to the flame.

In a clash with the Girondins, Camille affiliated himself with The Mountain (over-arching radical faction). The Mountain successfully crushed the Counter Revolutionaries and Girondins by accepting passive citizens into the National Guard and expelling the Girondins from the Assembly altogether.[1] After rumours spread that King Louis and his family were about to be rescued from their confinement at the Tuileries by Austrian forces, The Mountain took control, and with support from the National Guard and Third Estate, drove the Royal Family to the meeting place of the Legislative Assembly to await judgement. This moment radicalized the revolution, conceptualizing France as a republic and legalizing the arrest of political suspects.[2]

As Camille was changing the course of revolutionary direction and trying to use public participation to rid France of the Monarchy, Lucile was home: a transient space in which members of the Cordeliers passed through for sustenance and comfort before disappearing back into the fray. Describing herself as calm and assured, Lucile used her intellect to assure Danton, the conductor of this grand political move, that the events of August 10th would be realized as planned.[3] Evidently, Lucile was not only privy to knowledge of the inner-most circle of Paris’ political elite, her judgement and opinion were actually respected and sought after.

Previous analysis of this journal entry has dismissed Lucile’s character as meek: extracting that she cared little for the issue of the day, but only for the safety of her husband.[4] Rather, from the viewpoint of a contemporary framework, Lucile’s ability to look after others at the expense of herself repeatedly over the nights of August 9th, 10th and 11th demonstrates a courage and stoicism overlooked, perhaps because they were demonstrated within the private, domestic space. The ignorance of history books to these types of private acts of bravery, begs the question that perhaps there are many more examples, we are just looking in the wrong places. In contrast to the numerous explanations and depictions of the public, blood-soaked garden of the Tuileries, Lucile’s journal of these chaotic nights displays femininity as resilient and tough in time of crisis, in contrast to the normal associations of fragility and hysteria.

[1] Georges Lefebvre, The French Revolution (London: Routledge, 1930), 230 – 234.

[2] Ibid, 235 and Peter McPhee, The French Revolution 1789-1799 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2002),98.

[3] Primary Source

[4] Methley, Camille Desmoulins, 191.

2 notes

·

View notes

Quote

We want to be free. O God, the cost of it! As a climax to my misery, courage abandons me.

Lucile Desmoulins, August 9-11, 1792

0 notes

Text

Le Vieux Cordelier

The publishing of the Le Vieux Cordelier, a political journal aligned with the Dantonists, was a testament to Camille’s brash attitude about publishing his unfiltered opinions and Lucile’s unflinching support for her husband.

Initially a scathing critique of La Pere Duchesne, a radical newspaper edited by Jacques-Rene Herbert, Le Vieux Cordelier condemned the legislation of the Terror, most specifically the Committee of Public Safety and Law of Suspects.[1] Selling over 50,000 copies of the third and fourth editions, Camille believed himself to still have the support of his old friend Robespierre.[2] Robespierre’s initial support however was shrouded in warnings to cease publication, at the request of the National Assembly.[3] Blatant disregard for these warnings was fueled by Camille’s obsessive nature in which he was intent on exposing the tyrannical nature of the new government.[4] Drawing on his old Cordelier morals of government transparency and support for the oppressed, Camille likened Robespierre and his Jacobins to the oppressive rule of the emperor Titus.[5] Like Camille had once called for the Storming of the Bastille, he now called for the end of the Terror. Subsequently Camille was excluded from the Jacobins, the National Assembly and arrested as a suspect of the Revolution, his seventh edition of Le Vieux Cordelier to be published after his death.[6]

Lucile, instead of pleading with her husband to stop endangering their safety which hinged on their friendship with Robespierre, encouraged Camille in his exposé.[7] Refusing to be intimidated, Lucile had a serious confidence about Camille’s “mission [to] save his country”.[8]

This was not naivety shown by Lucile, but rather a remarkable, quiet courage. In a letter to a confidant, Louis-Marie Stanislas Freron, Lucile made it clear that she understood the danger that they were both in after the breakdown of friendship with Robespierre.[9] In a heartbroken tone, Lucile appealed for Freron to come back from Toulon as she began to find it hard to bare the Terror which engulfed Paris.[10] In admission that she had become recluse and despondent from her usual pleasures of society and piano, Lucile disclosed that when she is to look at Camille it is only with calmness, as she understood that he relied on her bravery.[11]

Lucile’s emotional intelligence, love for her husband and courage in the midst of impending doom is not recorded in many history books. How many more heroines could be found within the plethora of discarded pamphlets, ignored domestic roles and a rethinking of heroism within the private space?

[1] Methley, 227 and 238.

[2] Ibid, 242-243.

[3] Rachel Hammersley, “Camille Desmoulins’s Le Vieux Cordelier: a link between English and French republicanism,” History of European Ideas vol. 27, no. 2 (2001): 116.

[4] Ibid ,116.

[5] Ibid, 120.

[6] Ibid, 117.

[7] Methley, Camille Desmoulins, 263.

[8] Conversation between Lucile, Camille and Brune recorded in Jules Claretie, Camille Desmoulins and His Wife: Passages from the History of Dantonists Founded Upon New and Hithero Unpublished Documents (London: Smith, Elder and Company, 1876), 290.

[9] Original Letter from Lucile to Freron, found within Claretie, Camille Desmoulins and His Wife, 286.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid.

0 notes

Text

The Beginning of the End

Camille’s antagonization eventually forced Robespierre’s hand. After years of friendship, the witness to their wedding, the godfather of their child, Robespierre chose his Terror and the Revolution over the lives of Camille and Lucile.[1]

Camille was to be executed with the other members of the original Cordeliers, including Danton and d’Eglantine, charged with conspiring against the Revolution.

The impending death of her husband was compounded for Lucile by the fact that it was at the hands of their close friend. Denied any access to meet with him, probably due to Robespierre’s guilt, the betrayal Lucile felt was evident in the letter that she wrote and delivered to Robespierre, pleading for Camille’s life.[2] In a similar heartbreaking plea, Lucile’s mother wrote to Robespierre, directly appealing to any empathy he might have left, asking if he remembered bouncing his godson Horace on his knee.[3]

In the days leading up to his execution, Lucile wondered around the grounds of the Luxemburgh Prison where Camille was held, hoping to catch a glimpse.[4] Collected from Camille’s papers after his death was a letter to Lucile, clearly distraught he wrote “I feel myself about to launch into eternity! I still behold Lucile! I clasp her in my arms, I embrace her! And my heart, separated, reposes upon her”.[5]

[1] Methley, Camille Desmoulins, 285.

[2] A letter from Lucile Desmoulins to Maximilien Robespierre, found within Methley, Camille Desmoulins, 288.

[3] Ruth Scurr, Fatal Purity: Robespierre and the French Revolution (New York: Random House, 2012), 283.

[4] Methley, Camille Desmoulins, 288.

[5] Camille Desmoulins to Lucile Desmoulins, March 1794, Papers of Camille Desmoulins, The British Museum 1948, 0214.377.

0 notes

Quote

Good night, dearest mother. A tear falls from my eye for you. I will go to sleep in the tranquility of innocence.

Lucile Desmoulins, 1794

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Death of Lucile Desmoulins

After Camille’s execution, it was almost inevitable that Lucile, deeply embedded within the inner circle of the Cordeliers, would soon meet the same end.

From the extraordinary source of Charles Henri Sanson (her executioner), Lucile is described as in an intense “despair”, some thinking that she was actually insane during trial.[1]

As if accepting her fate, Lucile was to become hauntingly calm and serene: she did not weep and kept her composure as she placed her neck under the guillotine.[2] Her final sentiments were those of happiness: she expressed to the audience that her “only wish, since Camille’s death, has been to join him; this wish is now about to be accomplished”.[3]

The remarkable, short life of Lucile Desmoulins would end on April 13, 1794. She would be survived by her son Horace, and the preservation of her journal.

[1] Memoirs of the Sansons edited by Henri Sanson: Late Executioner of the Court of Justice of Paris, 1688-1847, Robarts – University of Toronto, ark:/13960/t5r789j67.

[2] Methley, Camille Desmoulins, 313.

[3] Ibid and Memoirs of the Sansons edited by Henri Sanson: Late Executioner of the Court of Justice of Paris, 1688-1847, Robarts – University of Toronto, ark:/13960/t5r789j67.

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bibliography

Primary Sources

Diary of Lucile Duplessis 7-9 July 1788. Found within Lejeune, P. On Diary. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2009.

Camille to Jean Benoît Nicolas Desmoulins, 24 December 1790. Found within Violet Methley, Camille Desmoulins; A Biography. London: Martin Secker, 1914.

Lucile Desmoulins to Louis-Marie Stanislas Freron, December 1793, found within Claretie, J. Camille Desmoulins and His Wife: Passages from the History of Dantonists Founded Upon New and Hithero Unpublished Documents. London: Smith, Elder and Company, 1876.

Memoirs of the Sansons edited by Henri Sanson: Late Executioner of the Court of Justice of Paris, 1688-1847, Robarts – University of Toronto, ark:/13960/t5r789j67.

Post 1: Lucile Desmoulins’ ‘Little Red Book’, 1771-1794, National Library of France, ark: / 12148 / bpt6k74578p.

Copyright: Florence Rochefort , " Lucile DESMOULINS, Journal 1788-1793 ", Clio. History, women and societies [Online], 4 | 1996, Online since 01 January 2005, connection on 28 September 2020. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/clio/452

Post 2: Rousseau, Jean-Jacques. Emile, or On Education. Geneva: unknown original publisher, 1762.

Post 3: Pierre-Gabriel Berthault and Jean-Louis Prieur, Motion made at the Royal Palace by Camille Desmoulins: July 12 1789, etching completed 1802.

Copyright: [Recueil. Collection Michel Hennin. Estampes relatives à l'Histoire de France. Tome 118, Pièces 10278-10385, période : 1789]. Identifier (FrPBN)41089369.

Post 4: National Library of France, Ego stultus propter Christum, 1790.

Copyright: Source gallica.bnf.fr / Bibliothèque nationale de France.

Post 5: Bibliotheque nationale de France, Les arcades du Café de Foy, 1790.

Copyright: Source gallica.bnf.fr / Bibliothèque nationale de France.

Post 6: National Library of France, Horrible attacks by Francois Comis in Paris on August 10, 1792, 1792.

Copyright: Source gallica.bnf.fr / Bibliothèque nationale de France.

Post 7: Camille Desmoulins, Le Vieux Cordelier, December 30, 1973.

Copyright: Source gallica.bnf.fr / Bibliothèque nationale de France.

Post 8: Camille Desmoulins to Lucile Desmoulins, March 1794, Papers of Camille Desmoulins, The British Museum 1948, 0214.377.

Copyright: The Trustees of the British Museum

Post 9: Jacques-Louis David, Portrait de Camille Desmoulins en famille, 1792.

Copyright: Photo RMN-Grand Palais

Secondary Sources

Abray, J. “Feminism in the French Revolution.” The American Historical Review, vol. 80, no. 1 (1975): 43-62.

Claretie, J. Camille Desmoulins and His Wife: Passages from the History of Dantonists Founded Upon New and Hithero Unpublished Documents. London: Smith, Elder and Company, 1876.

Darrow, M.H. “French Noblewomen and the New Domesticity, 1750-1850.” Feminist Studies, vol. 5, no. 1 (1979): 41-65.

Gliozzo, C.A. “The Philosophes and Religion: Intellectual Origins of the Dechristianization Movement in the French Revolution.” Church History, vol. 40, no. 3 (1971): 273-283.

Haine, S.W. The Word of the Paris Café: Sociability Among the French Working Class, 1789-1914. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 1998.

Hammersley, R. “Camille Desmoulins’s Le Vieux Cordelier: a link between English and French republicanism.” History of European Ideas, vol. 27, no. 2 (2001): 115-132.

Kerber, L. “The Republican Mother: Women and the Enlightenment – An American Perspective.” American Quarterly, vol. 28, no. 2 (1976): 187-205.

Lefebvre, G. The French Revolution. London: Routledge, 1930.

Lejeune, P. On Diary. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2009.

Lusebrink, H-J and Reichardt, R. The Bastille: A History of a Symbol of Despotism and Freedom. Durham: Duke University Press, 1997.

McPhee, P. The French Revolution 1789-1799. New York: Oxford University Press, 2002.

Methley, V. Camille Desmoulins; A Biography. London: Martin Secker, 1914.

Scurr, R. Fatal Purity: Robespierre and the French Revolution. New York: Random House, 2012.

Sewell, W.H. “Historical events as transformations of structure: Inventing revolution at the Bastille.” Theory and Society, vol. 25, no. 6 (1996): 841-881.

6 notes

·

View notes