Maïté Maeum JEANNOLIN is a French-Korean artist based in Brussels. After studying at P.A.R.T.S (Performing Arts Research and Training Studios), today her practice weaves together performance, film, photography, writing and curating. She works with choreographers as well as visual artists/video artists with whom she collaborates on performances, films and installation projects. She is currently directing her first feature documentary, which examines the transgenerational impacts of Korean overseas adoption. She is also involved in adoptee community work, contributing through articles, workshops, and organizing. #intersectional feminist #decolonial narratives #freepalestine

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

This speech was written for and read aloud at a protest in front of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission on April 10th, 2025, Seoul. The Protest was a joint movement from adoptee associations and human rights organizations : DKRG, FKRG, NLKRG, NKRG, CAFE, USKRG, AUSKRG, IbyangIN, KoRoot, ASF, SKAN.

ADOPTION ECHOES THROUGH GENERATIONS

I am here today, speaking in front of you as the daughter of a Korean adoptee. Many names can describe my position in this story: adult child of a Korean adoptee, 2Gen, or the one I currently like to use: a DoKAD (Descendant of a Korean adoptee).

I am part of the generation after—the one that inherits the gaps, silences, misinformation, lies, uncertainty, missing family members, unknown names, inaccessible past.

Most Koreans have heard of, or even met, adoptees looking for their families of origin; adoptees visiting the Motherland; adoptees connected to adoptee associations or even, as we witness today, adoptee activists advocating for their rights.

But in my view, these adoptees represent only a small fraction of Korean adoptees worldwide. The vast majority remains off the radar. Some have already passed away—some by taking their own lives. Others are grappling with severe mental health issues, carrying their trauma alone. Some have turned away from the past entirely, distancing themselves from the adoptee community. And some have simply blended in, built new families, and moved on.

My mother is one of them. She built a beautiful family with four daughters. She never searched for our Korean family of origin and, for most of her life, turned away from her Korean identity. At home, we rarely spoke about it openly—partly because it was such a sensitive, painful subject. But also, as I’ve come to understand, because it felt like there was simply nothing to say. Her adoption file states she was “abandoned,” with no details about where, when, or by whom she was found. From her perspective, that was all the information she could ever hope to have.

Therefore, she has put up with the idea that she was most likely abandoned by a poor family. Her story is a sad story— a story we better forget.

So did I, for most of my life, thinking that our past was buried somewhere, inaccessible.

But as I grew up, I had the chance to come into contact with adoptees who broadened my horizon. What if my mum's story, which oddly resembled so many other adoptee cases, was actually incomplete, inaccurate, or even completely fabricated?

In 2018, I went to Holt’s post-adoption services to ask about my mum’s file. But since I’m the daughter of an adoptee and not the adoptee herself, I wasn’t allowed to see anything. Talking to the social worker, I realized that the file my mum had always known might just be a fragment: the version sent to France was only a part of the Korean one. She said it was simple—adoptees just had to come to Korea and ask. I was in shock. Did they seriously think it was "simple" to look for something that was supposed not to exist?

Even then, we know that the agency would probably still keep some of it hidden. So wall after wall, lie after lie, it takes a lot of energy to engage in this type of journey. Not everyone wants to do it or has the resources to do so, whether psychologically, emotionally, or even financially.

And yet, even when we’re aware of these barriers, some of us feel compelled to keep searching — perhaps not for ourselves directly, but for those who came before us, or those who come after.

That’s why I feel that, as the daughter of an adoptee, I stand at a very interesting crossroads. Even if I don’t have the same trauma from adoption and abandonment as my mother, I carry so many questions, a desire to understand my family’s story and a grief for what has been taken away from us.

But legally, if my mum doesn’t want to take the steps to look into her past, it is currently impossible for me to find out more.

Although I respect my mum’s position, it strikes me that the Korean administration behaves as if it were only her story and her family. I think we, as children of adoptees, should have a legal right to access our information. And I insist—I say our because it’s strange to keep pretending it doesn’t concern us.

Think about it: in a "normal" family, if my mum were estranged from her own mother and didn’t want to be in contact with her, would I be deprived of the legal right to access my grandmother? No. In the end, it should come down to a personal choice: Will this damage my relationship with my KAD parent, or not? Will I take these steps, or not?

That’s my choice to make—not the government’s.

Throughout the years, I’ve encountered other people like me—other DoKADs—who are asking themselves similar questions. Although we share common ground, our experiences are very singular and show how adoption has affected us in different ways.

Marrit, whose KAD mum died by suicide, has been looking for her Korean family of origin. It was only through her grandparents—her mum’s adoptive parents—that she managed to get some information from the adoption agency. She tried asking NCRC about DNA testing and entering the database for missing children, but her request was rejected.

Lovijah, another DoKAD, recently tried the same path through her grandparents as well, but she couldn’t get anything at all.

Tanya, whose KAD mum died from cancer, was diagnosed with cancer years later. At the doctor’s office, they asked her: “Does this run in your family?” But she had no answer. Not knowing her medical history meant she couldn’t anticipate a genetic illness. And the consequences are real—sometimes, it’s a matter of life and death.

These stories remind us that, for now, when a Korean adoptee dies, Korean law ensures that their past is made forever inaccessible—sealed away from us.

That’s why today, I, along with other fellow DoKADs who are concerned with these issues, would like to ask for a TRC3.

We need to make sure that more cases can be investigated by a new commission. And we would also like to ensure that the TRC3 makes it possible for Descendants of adoptees to submit the adoption case of their KAD parent for further investigation, whether they have passed or don't want to submit it themselves.

This would be a meaningful step towards acknowledging that the loss and trauma of adoption do not end with the adoptees — they echo through generations. We carry this story too, even though we never chose to be a part of it. We were born into it, and we deserve the right to understand it.

Thank you.

저는 오늘 한국 입양인의 딸로서 여러분 앞에서 이 자리에 섰습니다. 이 이야기 속 제 위치를 여러 가지 이름으로 표현할 수 있습니다. 한국 입양인의 성인 자녀, 2세대, 그리고 제가 현재 즐겨 사용하는 DoKAD(한국 입양인의 후손) 등 말입니다.

저는 한국 해외입양의 다음 세대에 속합니다. 공백, 침묵, 잘못된 정보, 거짓말, 불확실성, 실종된 가족, 알려지지 않은 이름, 닿을 수 없는 과거를 물려받은 세대입니다.

대부분의 한국인들은 친가족을 찾는 입양인, 모국을 방문하는 입양인, 입양인 협회와 연계된 입양인, 심지어 오늘날 우리가 목격하듯이 입양인의 권리를 옹호하는 활동가들의 이야기를 들어보거나 직접 만나본 적이 있습니다.

하지만 제 생각에 이러한 입양인들은 전 세계 한국 입양인 중 극히 일부에 불과합니다. 대다수는 여전히 주목받지 못하고 있습니다. 이미 세상을 떠난 입양인도 있고, 스스로 목숨을 끊은 입양인도 있습니다. 또 다른 입양인들은 심각한 정신 건강 문제로 홀로 고통받고 있습니다. 어떤 사람들은 과거로부터 완전히 등을 돌리고 입양 공동체와 거리를 두었습니다. 그리고 어떤 사람들은 그저 사회에 녹아들어 새로운 가정을 꾸리고 살아갔습니다.

제 어머니도 그중 한 분입니다. 네 딸과 함께 아름다운 가정을 이루셨습니다. 어머니는 원래 한국 가족을 찾지도 않으셨고, 평생 동안 자신의 한국인 정체성을 외면하셨습니다. 집에서는 그 이야기를 거의 꺼내지 않았습니다. 너무 민감하고 고통스러운 주제였기 때문이기도 했지만, 제가 이해하기로는, 그저 할 말이 없는 것처럼 느껴졌기 때문이기도 했습니다. 어머니의 입양 기록에는 어머니가 "버림받았다"고만 적혀 있을 뿐, 어디서, 언제, 누구에 의해 발견되었는지에 대한 자세한 정보는 없었습니다. 어머니의 관점에서는 그것이 어머니가 바랄 수 있는 전부였습니다.

그래서 어머니는 가난한 가정에 버림받았을 가능성이 높다는 생각을 참아왔습니다. 어머니의 이야기는 슬픈 이야기입니다. 우리는 그런 이야기를 잊어야 합니다.

저도 마찬가지로, 평생 동안 우리의 과거가 어딘가에 묻혀 접근할 수 없다고 생각했습니다.

하지만 자라면서 제 시야를 넓혀준 입양인들을 만날 기회가 생겼습니다. 다른 많은 입양인 사례들과 기묘하게 닮은 엄마의 이야기가 사실은 불완전하거나, 부정확하거나, 심지어 완전히 조작된 것이라면 어떨까요?

2018년, 저는 홀트 입양 사후관리 센터에 가서 엄마의 기록에 대해 문의했습니다. 하지만 저는 입양인의 딸이지, 입양인 본인이 아니었기에 아무것도 볼 수 없었습니다. 사회복지사와 이야기를 나누면서 엄마가 항상 알고 있던 기록은 일부에 불과할지도 모른다는 것을 깨달았습니다. 프랑스로 보낸 기록은 한국 기록의 일부일 뿐이었습니다. 엄마는 간단하다고, 입양인들이 한국에 와서 물어보기만 하면 된다고 말했습니다. 저는 충격을 ���았습니다. 존재하지 않아야 할 것을 찾는 것이 "간단"하다고 생각하는 걸까요?

그렇더라도 기관은 아마도 그 기록의 일부를 숨길 것이라는 것을 알고 있습니다. 그래서 벽을 쌓고, 거짓말을 거듭하며 이런 여정을 시작하려면 ��청난 에너지가 필요합니다. 모든 사람이 심리적, 정서적, 심지어 재정적으로 그렇게 하고 싶어 하거나 그럴 자원이 있는 것은 아닙니다.

그런데도 이러한 장벽을 인지하고 있음에도 불구하고, 어떤 사람들은 계속해서 찾고 싶어 합니다. 어쩌면 자신을 위해서가 아니라, 우리보다 먼저 왔던 사람들이나 우리보다 나중에 올 사람들을 위해서일지도 모릅니다.

그래서 저는 입양인의 딸로서 매우 흥미로운 갈림길에 서 있다고 느낍니다. 비록 어머니처럼 입양과 유기의 트라우마를 겪지는 않았지만, 저는 수많은 질문과 가족의 이야기를 이해하고 싶은 열망, 그리고 우리에게서 빼앗긴 것에 대한 슬픔을 안고 있습니다.

하지만 법적으로, 어머니가 과거를 돌아보려는 조치를 취하지 않으신다면, 저는 현재 더 많은 것을 알아낼 수 없습니다.

저는 어머니의 입장을 존중하지만, 한국 정부가 마치 어머니와 그녀의 가족 이야기만 다루는 것처럼 행동하는 것 같습니다. 입양인의 자녀인 우리는 자신의 정보에 접근할 법적 권리가 있어야 한다고 생각합니다. 그리고 저는 우리와 상관없는 척하는 것이 이상하기 때문에, '우리'라고 말합니다.

생각해 보세요. "정상적인" 가정에서 만약 제 어머니가 친어머니와 떨어져 지내고 어머니와 연락하고 싶어하지 않는다면, 저는 할머니와 접촉할 법적 권리를 박탈당할까요? 아닙니다. 결국 이는 개인의 선택에 달려 있습니다.

이것이 KAD(한국입양인) 부모와의 관계에 악영향을 미칠까요, 아니면 안 미칠까요? 이러한 조치를 취할까요, 아니면 취하지 않을까요?

그것은 제 선택이지 정부의 선택이 아닙니다.

지난 몇 년 동안 저는 저와 비슷한 질문을 스스로에게 던지는 다른 DoKAD(입양인2세)들을 만났습니다. 우리는 공통점을 가지고 있지만, 우리의 경험은 매우 독특하며, 입양이 우리에게 각기 다른 방식으로 어떤 영향을 미쳤는지 보여줍니다.

KAD(한국입양인) 어머니를 자살로 잃은 Marrit은 한국 출신 가족을 찾고 있습니다. 그녀는 조부모님, 즉 어머니의 양부모님을 통해서야 입양 기관으로부터 정보를 얻을 수 있었습니다. 그녀는 NCRC(아동권리보장원)에 DNA 검사와 실종 아동 데이터베이스 입력에 대해 문의했지만 거절당했습니다.

또 다른 DoKAD인 로비야는 최근 조부모님을 통해 같은 방법을 시도했지만 실패했습니다.

KAD(한국입양인)으로 힘들어 하셨던 어머니를 암으로 잃은 로비야는 몇 년 후 로비아는 암 진단을 받았습니다. 병원에서 의사는 그녀에게 "가족력인가요?"라고 물었지만, 그녀는 아무런 대답도 하지 못했습니다. 자신의 병력을 알지 못했다는 것은 유전 질환을 예측할 수 없다는 것을 의미했습니다. 그리고 그 결과는 현실이며, 때로는 생사가 걸린 문제입니다.

이러한 이야기들은 현재 한국 입양인이 사망하면 한국 법이 그들의 과거를 영원히 접근할 수 없도록, 즉 우리가 알 수 없도록 봉인한다는 것을 우리에게 일깨워줍니다.

오늘 저는 이 문제에 관심을 가진 다른 DoKAD 회원들과 함께 제3기TRC(제3기진실화해위원회)를 요청하고자 합니다.

새로운 위원회가 더 많은 사건을 조사할 수 있도록 해야 합니다.

또한 제3기TRC를 통해 입양인의 후손들이 사망했든 직접 제출하고 싶지 않든 KAD 부모의 입양 사건을 추가 조사를 위해 제출할 수 있도록 해야 합니다.

이는 입양으로 인한 상실과 트라우마가 입양아에게만 국한되지 않고 세대를 거쳐 울려 퍼진다는 것을 인정하는 의미 있는 발걸음이 될 것입니다. 비록 우리가 선택하지 않았더라도, 우리 역시 이 이야기를 품고 있습니다. 우리는 이 이야기 속에서 태어났고, 이해할 권리가 있습니다.

Maïté Maeum JEANNOLIN

0 notes

Text

Last year, the DKRG filed a petition to the South Korean government’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC)– which has been investigating human rights abuses – asking it to look into abusive and corrupt adoption practices. DKRG and the Korean internet newsmedia Pressian have for one year been publishing essays written by adoptees and their families about the truth. These stories have given voice to unheard adoption experiences and been instrumental in reaching the ordinary Koreans. Now that the TRC has been extended for a year, I was asked to share my thoughts about reconciliation, the other half of ‘truth and reconciliation’.

HOW TO RECONCILE WITH OUR PAST WHEN IT'S STILL OUR PRESENT ?

To begin with, I thought it would be good to clarify where I'm writing from: a particular point of view, that of the daughter of an adoptee.

My mother was adopted to France into a Christian family at the age of 4. She never spoke openly about South Korea or adoption and has never returned to South Korea. She still doesn't know the circumstances of her abandonment or the identity of her Korean biological family. She doesn't want to look for them and even forbid me to do the research myself because: she's been through enough trauma, she doesn't need any more.

There are many ways of dealing with a painful and enigmatic past. My mother decided to sweep it under the carpet and reject her Korean identity.

As far as I'm concerned, I grew up far from my Korean heritage and a sense of belonging to a diasporic community. Half Korean and half white, I was brought up as a French country girl, surrounded by mostly white people - most of whom were racist - and I did my best to assimilate, as my mother did throughout her life. I even drew up personal statistics: I felt 90% French and 10% Korean, twice estranged from my heritage : once by the adoption and acculturation of my mother, a second time by her silence. Perhaps this sounds very familiar to Korean adoptees themselves, but ironically, as the daughter of a Korean adoptee who hadn't come to terms with her past, I felt like I was being denied access to parts of my story.

There were things we shouldn't talk about because they were too painful and made our parent suffer. The questions we shouldn't ask because there were no answers anyway. The things we shouldn't mention because they might cause an argument. In the end, we (my three sisters and I) got used to the fact that there was no story worth telling.

Interestingly, when stories are lost or silenced, we make up new ones or repeat the only ones we had access to. And often, they aren't the most original: South Korea was very poor after the war, many orphans had to be "saved". Adoption was the only and best solution. We should be grateful for that life-changing opportunity and forget about our pitiful past.

As I write today, this sounds caricatural, almost grotesque. But I still remember that growing up, it would have been unimaginable to question this, precisely because it was my only truth. I was blind to adoption as a phenomenon at the intersection of politics, colonialism, capitalism and patriarchy.

It was just the story of my mum, a sad story we better forget.

Later, when I left the French countryside for a more multicultural environment, I met people who were mixed-race like me and who had a better understanding of their identity. Only then, I began to re-read my own family history in a new light. I started questioning international adoption and building a critical perspective. I realized that my mother was one person in 200,000 or 250,000. The narrative we had made up - she had been abandoned on the streets because her parents were too poor to look after her - was beginning to sound too repetitive, self explanatory and almost manufactured. So what was the truth then ?

Well... to be honest, I have accepted that we'll never get to the bottom of it. On one hand because my mother doesn't want to do any research (so far) - and I respect that -. On the other hand because South Korea and France have not made this information available, accessible or reliable.

Then, without the horizon of truth, what could reconciliation mean for me?

At first, I wondered what kind of reconciliation we were talking about. A global reconciliation between "those who have been wronged" and "those who have wronged"? A legal reconciliation? A family reconciliation? A symbolic reconciliation with one's story? A reconciliation between whom and whom exactly ?

Korean international and trans-racial adoption involves a multitude of stakeholders who are impacted and/or implicated: the adoptees of course, but also their biological families, their descendants, their adoptive families, the social workers, the adoption agencies (Holt, KWS, KSS, Eastern), the Korean government, the governments of the receiving countries, the protestant church, etc. Despite a semblance of a common denominator, I think that reconciling means and involves something radically different depending on the person or institution with whom we undertake this process.

Etymologically, re-conciliation implies to re-bring together, restore. It’s the process of people, or countries, or entities, agreeing to restore viable and constructive relations, despite the strongest convictions of the impossibility of the task and despite the immense pain previously inflicted.

But as a small reminder, Korean overseas adoption has existed for 70 years now and no measures have been taken to regulate the scale of this practice, which has been contested for more than 30 years. South Korea has signed the Hague Convention on Protection of Children and Co-operation in Respect of Intercountry Adoption but has never ratified it - and therefore never implemented it -. Although the various abuses suffered by adoptees and their families of origin have been widely reported in the media, it has not altered the dominant narrative on either side of the world: "Adoption was the best solution, for the well-being of the children" nor has it put an end to intercountry adoption from South Korea.

Then, how to reconcile with our past when it’s still our present ?

For me, reconciliation implies a mutual commitment towards collective transformation. It is not an idea or a good intention (one more), nor something we can do on our own. But a process that requires material and symbolic actions, from both sides.

In order to personally reconcile with my story, more than the specific truth about my mother -which might stay forever out of reach-, I need from the Korean government what truth-fullness requires: Apologies, Acknowledgment, Accountability, Consistency, Transparency, Reparation, Care and Rights.

Among others things :

-Full access to adoption documents and identity information to adoptees. -Access to adoption documents and identity information extended to the descendants of adoptees. -A thorough investigation when human rights violations are suspected. -Centers where intercountry adoptees and descendants can gather in South Korea. -Financial support for intercountry adoptees to receive psychotherapy. -Travel costs for intercountry adoptees and descendants to visit South Korea to find their original family. -Free DNA test for intercountry adoptees, descendants and birth families. -Matching of DNA samples of intercountry adoptees and descendants to all DNA databases currently present in South Korea.

I personally believe that individual and collective reconciliation are intimately intertwined: our incomplete truths can resonate with those of others. They hold together and allow us to break out from our solitude, from the burden of autobiography.

These coming years, I sincerely hope we'll find a balance between the peace everyone deserves and the strength still required to expose those who need to be held accountable. Hopefully then, what will disappear is not the memory of what happened but the trauma it generated. Perhaps the repercussions of intercountry adoption will stop being passed down from generation to generation. And we will be able to go on, with a lighter heart.

Maïté Maeum JEANNOLIN

0 notes

Text

ADOPTEES URGE NEW INVESTIGATION AND JUSTICE AFTER SOUTH KOREA CONFIRMS ADOPTION ABUSES

Very happy to be featured again in the Korea Herald among other speakers who voiced their concern about the current Truth and Reconciliation Commission. Full article under :

This is no longer just a matter for investigation. It’s a matter for prosecution,' says adoptee group leader

Adoptee advocacy groups from all over the world gathered outside South Korea’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission in Seoul on Thursday, calling for a new round of investigations — and legal accountability — over systemic malpractice in the country’s intercountry adoption program.

The demonstration comes around two weeks after the independent commission on March 26 announced that it had identified human rights violations in 56 of the 367 adoption cases submitted since 2022.

As of March 26, the commission said it had completed investigations and issued reports for 98 cases — only about 26 percent of the total. Of those, 42 were dismissed due to “insufficient evidence,” leaving just 56 cases officially recognized.

The remaining 267 cases have already been investigated, but their final reports are still being written. However, with the mandate for this TRC -- South Korea's second in history -- set to expire May 26, it remains unclear how many of these will result in official acknowledgment before this commission’s mandate ends.

A TRC official cited the “sheer scope and complexity” of the cases as the main reason for the delay.

“Our message is simple,” said Peter Moller, a lawyer born in Korea and adopted to Denmark, who is co-founder of the Danish Korean Rights Group. “If all 367 adoptees cannot be recognized, a new commission must and shall be established — one that allows new applications.”

Moller stressed that the burden of proof should not fall on the adoptees themselves -- as victims whose records were deliberately destroyed or falsified, in other words, whose human rights were violated through illegal adoptions.

“That’s how the rule of law works,” he said.

Advocates are also pushing for criminal prosecution — not just fact-finding.

“This is no longer just a matter for investigation,” said Min Young-chang, co-chair of the Adoption Solidarity Coalition. “It’s a matter for prosecution.” Min argued that the missing documentation itself signals wrongdoing, not a lack of evidence. “Information that doesn’t exist — that is the evidence,” he said.

Min called for certain cases to be referred to prosecutors and the National Assembly, if necessary.

Other speakers at the rally shared stories that reflect the long-term effects of South Korea’s adoption policies.

Cho Min-ho, director of the Children’s Rights Solidarity, recounted being labeled an orphan by the state despite having living parents. “I was intentionally made into an orphan,” he said, condemning the erasure of identity as a violation of both Korean constitutional rights and the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child.

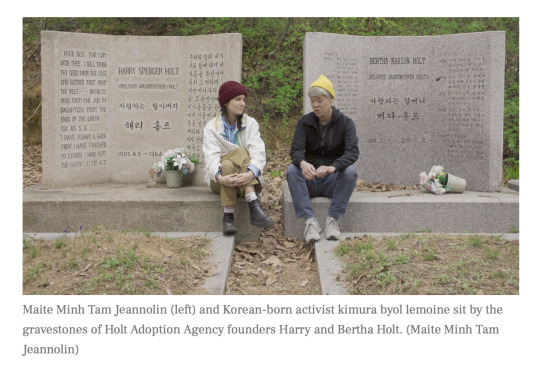

Maite Maeum Jeannolin, a filmmaker and daughter of a Korean adoptee to France, highlighted the lasting consequences for adoptees' descendants. Under current Korean law, adoption records are permanently sealed after an adoptee’s death — even from their own children. “We deserve the right to understand it,” she said, referring to descendants' rights to search for their biological families.

Ben Coz, a Korean adoptee to the US and member of international network ibyangIN, called access to birth and adoption records “a human right,” citing international child rights law and professional ethics standards. He encouraged adoptees and supporters in receiving countries to advocate for policy changes at home, as governments like Norway and the Netherlands open their own investigations.

He urged adoptees and allies abroad to contact lawmakers, noting that more countries — like Norway and the Netherlands — have launched their own investigations.

Many demonstrators said they were unable to apply to the current TRC before the application window closed and are now left without any path to official recognition or redress.

“This isn’t history,” said Min, reacting to recent remarks by TRC Chair Park Sun-young, who called the adoption abuses “a thing of the past.” Min disagreed, saying, “It’s still happening.” Moon Joon-hyun. [email protected]

0 notes

Text

WORKSHOP DoKAD SEOUL

The first generations of Korean adoptees often started their own families, and today, a new generation is speaking up: their descendants.

Some of us live, study or visit Korea, sometimes with our Korean adoptee parent, sometimes without. How has adoption impacted us ? What are we looking for in Korea ? What legal rights do we have ?

Maïté 마음 JEANNOLIN, Bastiaan Seo Vin Flikweert and Marrit Kim will facilitate these discussions in a supportive and inclusive environment through different games. This workshop will be an opportunity to share our experiences and reflect together on our specific relation to our identities.

Seoul, Mugyewon Saturday, April 5 2025 2-6 PM

Event supported by Koroot- Adoptees’ Embassy in Korea

#Seoul #workshop #community #DoKADs #overseasadoption #nextgen

0 notes

Text

ADOPTION : REGARDS CROISÉS ET RÉCITS PARTAGÉS

Maïté Maeum Jeannolin, kimura byol lemoine et Kyung Wilputte proposent un espace de partage autour de récits liés à l’adoption, en engageant une réflexion sur nos (non)-privilèges. Ces échanges s’articuleront à travers des expressions artistiques.

Les trois artistes, issu·e·s de la constellation de l’adoption, accompagneront chaque participant·e selon leurs besoins, tout en veillant à offrir un cadre sûr et bienveillant, propice à l’émergence d’histoires et à la création de liens.

Théâtre de la Parole Á contre courant : Créolisations à l’œuvre 15 février 2025, 14-17h

https://www.theatredelaparole.be/produit/atelier-participatif-adoption-regards-croises-et-recits-partages/

0 notes

Text

VER VAN HIER / FAR FROM HERE GENERATIONS

We’re all “children” of our first parents, and whether we realize it or not, our parents and family—including extended family, ancestors, and culture—are integral to our system. How does that influence us? The same holds true for our own children, who are part of this shared system. What do we pass down to them, and how do they navigate the inherited parts of our shared adoptive background?

Film screening + panel talk moderated by filmmaker and adoptee Daan Vree with DoKAD speakers : Maïté Maeum Jeannolin and Jiri Moonen.

• The Chinese Empress (NL, Jonnah Bron, 27 min) • Geographies of Kinship (USA/South Korea, Deann Borshay Liem, 86 min)

VER VAN HIER Studio De Bakkerij November 7, 2025 8-10.30pm

0 notes

Text

CAN I PEEL AN ORANGE FOR YOU ? So excited to share the publication of the first zine from @st1ckyr1ce_brussels . I contributed with the english version of the piece I wrote about reconciliation from my perspective as a DoKAD.

HOW TO RECONCILE WITH OUR PAST WHEN IT'S STILL OUR PRESENT ?

The text is in very good company : voices, artworks, fragments from the many Asian diasporas in Belgium. Get your copy and support their work !

0 notes

Text

ATELIER DoKAD à KAB

Tellement fière de ce jeu de cartes créé pour le premier atelier destiné aux DoKAD de Belgique. Merci à celleux qui étaient présent.e.s d'avoir accepté de mettre en commun leurs experiences avec beaucoup de vulnérabilité.

Merci à kimura bol Lemoine d'avoir embelli ces cartes avec son magnifique travail ✨️ Merci à Yuna Chun Lee et Lee Lebens d'avoir contribué à développer les questions du jeu. Et merci à KAB (Korean Adoptees in Belgium) pour l'invitation, hâte de la suite 🔥 #DoKAD #overseasadoption #communitywork

0 notes

Text

DECOLONIZING ADOPTION AND CREATIVE RESISTANCE

Dreamed Up & Organized by liberation weaver + adoptee @writingtochangethenarrative and historian @rosecolored_scholar + founder of @antiracistliberation

Meet the artists, creatives, and co-alchemists who are joining us this November for #DecolonizingAdoption. From discussing the histories of international adoption and expanding scholarship around adoptees, to creative resistance through art therapy and ancestral returns, this is a virtual series you don’t want to miss!

How does adoption mark one’s ancestors and touch their descendants? Meet the team behind this November’s public program “Inherited Gaps” who are sharing their stories, their creative making, and their multigenerational practice to recovering community, descendancy, and family histories.

#DoKAD #familyhistory #InheritedGaps #KoreanHeritage #adoptioncommunity #DecolonizeInstagram #communityovercolonialism #AdoptionIndustrialComplex #DecolonizingAdoption #KoreanAdopteeDescendants #creativeresistance #nationaladoptionawarenessmonth

0 notes

Text

IN OUR OWN WORDS So proud of being featured as 1 of the 43 stories in this Adoption Anthology compiled by Danish Korean Rights Group. Special thanks for the invitation to Han Boon Young. Fighting 화이팅 ! #overseasadoption #DoKAD #transgenerational

Press review : https://www.koreatimes.co.kr/www/nation/2024/10/113_383976.html

0 notes

Text

ECHO(E)S

J'ai eu le grand plaisir d'accompagner la réalisatrice Chloé De Bon sur son film Echoes en tant qu'assistante à la réalisation et regard extérieur sur la chorégraphie/accompagnement par le mouvement.

Le film ‘Echo(e)s’ visibilise les expériences souvent minimisées et banalisées qui se vivent lors d’un suivi gynécologique ou obstétrical. Il se construit sur le récit de huit personnes, en paroles et en mouvements, sur terre et dans l’eau, pour (re)questionner les pratiques de soin par le soin.

https://www.echoes-movie.com

0 notes

Text

A CONVERSATION WITH DESCENDANTS OF KOREAN ADOPTEES

We hosted a panel talk in Seoul where we shared some of our experience as Descendants of Korean Adoptees (DoKAD). Huge thanks to Koroot for the support in co-organizing this event. And of course thanks to the marvelous audience of KADs, DoKADs, Korean diaspora, friends, activists and researchers who came to support us and listen to us.

🎥 Full recording of the panel talk : https://vimeo.com/958241304

The talk was recorded and uploaded online for community purpose and for the use of the upcoming documentary film of Maïté Maeum Jeannolin.

0 notes

Text

UNSEEN INHERITANCE: TRAUMA OF TRANSNATIONAL ADOPTION TRICKLES DOWN TO ADOPTEES' CHILDREN

Honored to have been interviewed (among other DoKAD) by Amber Roos for The Korea Herald. Read full article here :

As South Korea’s dark past of international adoptions continues to unravel, an unexpected second storm has emerged. Intergenerational trauma -- a concept from the field of counseling psychology that has come into wider use in recent years -- is connecting a generation of adoptees' children feeling the effects of their parents’ adoption experiences.

With their newfound collective voice, adoptees' children are raising awareness for their community and the need for clarity on their rights as a generation.

“Even though it’s not me but my parents who were adopted, their adoption impacts me to the core,” said Bastiaan Flikweert, a Korean studies master’s student at Yonsei University in Seoul and the son of two Korean Dutch adoptees.

“When kids asked me why I looked different, the automatic response was that my parents were adopted," he said, explaining how much a part of his life his parents' adoption was. "I don’t think I even knew what the word ‘adoption’ meant at the time.”

Flikweert co-moderates a Facebook group specifically for descendants of Korean adoptees. Despite being in its infancy, the group is expanding quicker than he expected, reflecting the growing need for community among them, he said.

Parents' adoptions, children's questions

Since the end of the Korean War in 1953, an estimated 200,000 South Koreans have been sent overseas for adoption, mainly to the US and Europe and into white families. In post-war times, the humanitarian narrative of saving orphans from poverty convinced many parents to adopt a Korean baby -- many unaware of the ramifications it would have.

Although there is now more understanding of the distress adoptees experience during and after adoption, the effect of the process on their children has not yet been fully recognized.

Meeja Richards, a Korean American who grew up with a deaf Korean adoptee mother, has no doubt that her mother’s adoption impacted the way she was raised.

“I relate a lot with the problems that Korean adoptees face as well, like fear of abandonment and fear of homelessness, which is interesting because I don't really have a reason to have those experiences. So I think something in the way that my mom parented me must have influenced that,” Richards said.

Flikweert is currently working with an interdisciplinary team of researchers led by Boston College associate professor of counseling, developmental and educational psychology Oh Myo Kim to research the adult children of Korean adoptees. Through a series of surveys and interviews, they explore topics such as identity and socialization.

A recurring topic that Flikweert and Kim observed was a feeling of “in-betweenness.”

“There's a lot of ambiguity that came up in the interviews, either around the racial-ethnic identity, around the adopted community, around whether or not they can search or not search. There's a lot of uncertainty about where to go, where they fit in the story,” Kim explained.

Korean French artist Maite Minh Tam Jeannolin, also a co-moderator of the Facebook group, has several experiences with this in-betweenness. Growing up in the predominantly white countryside of the French Alps, she experienced racism in several facets of her life.

Even at home, her mixed Korean French ethnicity was the elephant in the room. It was only when she moved to a more multicultural environment that she realized how strange her situation was.

“My mom used to not identify as a Korean person. She identified as a French person. I think we can say she grew up totally whitewashed in the sense that she did not even perceive herself as Asian, nor did I,” Jeannolin said.

Right to roots

The discrepancy between Jeannolin’s curiosity about her Korean roots, and her mother’s desire to leave the past behind, was at times a cause for friction between the two.

Jeannolin said, “My mom once told me that it was her story, not mine. I said, ‘Look, it's not just your story. I know I will never go through everything you went through, but when you have a child, part of your story, part of that trauma, trickles down.’”

At the same time, she fears that looking for her biological family while her mother forbids her from doing so might have detrimental effects on her mother’s well-being and their relationship.

“For me, it raises the question of what our rights and responsibilities are as second generation, ethically as well as on a legal level," she said.

Twenty-three-year-old Iwan Scheer, born and raised in the Netherlands, recently made his first trip to Korea. Sadly, his father was not prepared to join him. While Scheer is curious to know more about his Korean family, he respects his father’s wishes not to search for them.

“My dad would get angry whenever I brought up the adoption,” Scheer recalled. “I remember how annoyed he got when he was gifted a traditional hanbok at a family gathering.”

Although their parents preventing them from digging deeper into their past can be frustrating for the descendants of Korean adoptees, Kim speculates that many parents do so in an attempt to shield their children from their trauma.

“I think some parents worry about imposing their trauma on their children. It's a protectiveness of, ‘Can't they just be clean? Can't they just be normal and we just carry our own stuff?’ But the truth is, the children will most likely be impacted by this because the parents are impacted by this,” the professor said.

However, it is not just direct family members that hinder the children of Korean adoptees from finding information about their Korean roots. Richards, who has dedicated her Instagram account to connecting with other children of adoptees and sharing her journey of searching for family, recalled an interaction that rubbed her the wrong way.

“When I told them, 'I’m looking for my grandmother,' they asked me whether I had my mother’s consent. Consent is very important to me, but it felt weird and unfair that I needed consent to find my own family.”

Birth of a community

With the birth of the community, Flikweert hopes to create a safe space for the descendants of Korean adoptees to share their experiences and feel less lonely. Many members are making an effort to spread awareness through various media.

Jeannolin is planning to release a feature documentary film, currently under the working title, "(M)other Land," in the fall of 2025. Through the film, she shares her experience as the child of an adoptee.

“This film is a way for me to dig deeper into my own story, but also to share the intergenerational aspect of adoption with a broader audience.”

Psychology professor Kim, who is a Korean American adoptee herself and mother of two children, was surprised to find that the children of adoptees were affected so deeply by their parents’ experiences.

“I didn't expect so much trauma in the interviews… it was heavier than expected. It's hard to say what the cause was because everybody was different, but there was a lot of sadness in the interviews,” she said.

Although there has been mixed feedback, with some adoptees expressing confusion about the need for a community of their children, there has been an abundance of positive feedback from members and participants.

“Of all the studies I’ve done, this was the one where participants were the most thankful. They thanked me for acknowledging their presence. And there have been a lot of great responses from adoptees who never thought about the children being part of the narrative in that way,” Kim said.

0 notes

Text

SELECTION - SIC 2024

Very happy to announce my selection at SIC -SoundImageCulture-2024. Looking forward to further develop my upcoming documentary film (M)OTHER LAND.

SIC is a nomadic platform in Brussels for the development of unique audiovisual projects at the intersection of film, art and visual anthropology. An open laboratory: SIC offers a year-long working process to develop your film project.

SIC works as an open laboratory: it offers a year-long working process during which its participants develop their artistic project. Through collective sessions, individual mentoring masterclasses and workshops, SIC encourages reflection on aesthetic and ethical choices and the development of new artistic approaches.

0 notes

Text

SEOLMUNDAE

Video. 5.13'

Ma mère a été adoptée en France depuis la Corée du Sud. Elle n'a pas connu sa mère biologique et je ne connaîtrai jamais ma grand-mère. Dans une lettre qui lui est adressée, un paysage s'ouvre : celui d'une terre tout aussi inconnue, une montagne, un volcan.

My mother was adopted to France from South Korea. She doesn't know her biological mother and I will never meet my grand mother. In a letter addressed to her, a landscape opens up: that of an equally unknown land, a mountain, a volcano.

Concept et réalisation : Maïté Minh Tâm Maeum Jeannolin, Dessin : Elisabeth, Elli, Selah & Arielle Abreu, London/Jeju-do/Belgium, 2023.

0 notes

Text

EXHIBITION 해외입양 70년, 뿌리의집 20년 - 70 years of Overseas Adoption, 20 years of KoRoot.

To celebrate the 20 years of KoRoot’s existence and its closing event of the guesthouse, the artworks of 20+ overseas Korean adoptee and their descendants will be on display July 7-21/2023.

Artists : Michou Amenlynck, Lia Barrett, Nari Baker, Raphaël Bourgeois, JooYoung Choi, Jennifer Kwon Dobbs, Florian Bong-Kil GROSSE, Lee Herrick, Maïté Minh Tâm Jeannolin, Jung, Maja Lee Langvad, Julayne Lee, kimura byol lemoine, Eunha Lovell, MehAhRi, Cathy Min Jung, Leah 양진Nichols, Mirae kh RHEE (이미래/李未來), Lisa Wool-Rim Sjöblom, Ji Sun Sjögren, Tanja Sørensen/Heeja Kramhøft, Kim Sperling, KimSu Theiler.

Family Tree, 2023 (Color print & post-it) Maïté Minh Tâm Maeum Jeannolin

"As the child of a Korean adoptee in France, I would like to question the trans-generational impacts of international adoption through the lens of transmission. Materializing the export of children by Korean adoption agencies to western countries, the map plays with the idea of Korean adoptee diaspora as extended family or ancestry".

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

OUVERTURE - Pièce pour danseur.euse.s et public cheminant

Il est important dʼavoir un secret, une prémonition des choses inconnues. Lʼêtre humain doit sentir quʼil vit dans un monde mystérieux et que des choses inexplicables se produisent et sont vécues. Alors seulement, la vie sera complète. (CJ) La troisième création de la danseuse et chorégraphe Géraldine Chollet sʼinspire de la tradition médiévale du Théâtre des Mystères. Ces cérémonies communautaires servaient à convoquer lʼau-delà afin de demander une grâce, dʼattirer la bienveillance ou de se remettre en question. La chorégraphe propose ici dʼouvrir un dialogue avec le sensible afin dʼexplorer les relations entre ce qui nous a été donné et ce que nous laisserons après nous. Reconnaître ce que nous avons, assumer ce quʼil nous manque, célébrer ce qui peut venir.

Chorégraphie Géraldine Chollet | Interprètes Mélissa Guex, Bastien Hippocrate, Eléonore Heiniger, Maïté Minh Tâm Jeannolin, David Zagari | Assistant Patrick Mangold | Créatrice Sonore Renée Van Trier | Créateur lumières et scénographie Sven Kreter | Composition musicale Raphaël Raccuia | Création costume Scilla Ilardo | Production & Administration Laetitia Albinati | Création imageAriane Beetz | Lumières et scénographie Justine Bouillet, Céline Ribeiro | Diffusion : oh la la - performing arts production.

0 notes