Text

TES III - Morrowind: Environmental Storytelling at its Finest

You are a new-fangled adventurer, fresh off the ship. Eager to explore the newly-discovered, alien world, you buy some supplies at the town merchant and set off immediately. But on the very outskirts of the harbour town, barely few hundred meters from the last house, something completely unexpected happens. You hear a heart-rending scream, and then, out of thin air, a human being appears some 30 meters above your head. Of course, the laws of gravity apply even on this fantastical world, and the inevitable happens. Next thing you know, the poor person is laying dead in front of you. Who was he? Why did he fall from the sky? Would it be a criminal offense to wear his expensive robes?

youtube

For many, including the author of this essay, this was probably the first time they have experienced environmental storytelling. Henry Jenkins says that “environmental storytelling creates the preconditions for an immersive narrative experience in at least one of four ways: spatial stories can evoke pre-existing narrative associations; they can provide a staging ground where narrative events are enacted; they may embed narrative information within their mise-en-scene; or they provide resources for emergent narratives. In other words, this time Bart Stewart’s, it “characterises environmental storytelling as something that “shows the final outcome of a sequence of events, then it invites players to make up their own stories about what happened to cause that outcome”. Which is exactly what happened in the first paragraph.

The game discussed is the third rendition of The Elder Scrolls saga, Morrowind. Released in 2002, it jump-started the popularity of this series. It is also the installment that is universally celebrated by fans of the Elder Scrolls series as the best one so far. The reasons for this can be manifold, but an average fan is most likely not going to mention its ultra-realistic graphics or ground-breaking combat system. Admittedly, compared to other titles in that era of game development, it left a lot to be desired. The game was riddled with bugs, the visuals were slightly outdated even on launch, and the game mechanics were clunky at best. But it did not matter at all, because the game excelled in other aspects, primarily world-building, an attribute closely tied to environmental storytelling. Indeed, without it, it would have never reached its popularity. “Worldbuilding will never save a bad game, but it is an element that elevates good games to something greater”, Josh Bycer says. This is, objectively, the strongest part of the game, and probably of the whole Elder Scrolls series. But it is Morrowind that resonates with the fans of the series the most. Bethesda, the creators of the series, were never fans of hand-holding, and Morrowind shows that. Instead of a modern GPS system with a minimap showing all the quest locations, the player is provided with a written description of their destination, usually with some landmark being mentioned to further narrow the area that the player has to explore in order to arrive at their point of interest. Not only that this makes careful worldbuilding a crucial part of the game, without which the player would not even be able to progress, but it opens door to environmental storytelling.

There is a moment in the game which serves as a great representation of such conjunction. The island of Morrowind, from which the game got its name, is filled with ruins. They were once inhabited by the Dwemer, an ancient race of technically-gifted dwarves. But for some reason, they have all suddenly disappeared, leaving those ruins behind them. Whatever happened, no-one is able to figure it out. The player visits the ruins on many occasions, when questing or exploring. And the latter is sometimes much more rewarding. As seen in the picture, there are two piles of ash on a bed frame, a flask of oil and an elongated “dwemer tube”. Now, a player who does not pay much attention to detail might not even notice this, storming through this location on their way to the next goal. Someone else might just disregard it as clutter and useless rubble. But there are people who will see a story behind this. A story that one might consider to be the very last romance of the now extinct race. Scenaros pertaining to as to what could have happened immediately start racing through the head of this attentive player. Of course, the game can be completed without even stumbling upon the whole dwemer mystery, as the knowledge of what happened to them has no direct impact on the main quest. Besides, it is never directly revealed, the player can only speculate and ultimately decide on what the cause could have been, modifying and creating their own lore. This is exactly what made Bethesda such an accomplished developer. They do not explicitly tell the players what to do, they just provide them with tools necessary to enjoy the vast, open world packed with experiences like this.

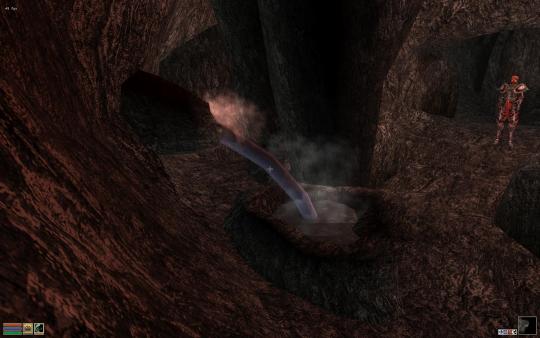

Another intriguing subject that the players may discover on their journeys throughout Tamriel (the world of Morrowind) is this seemingly uninteresting pool of water. But upon further inspection, a small information pop-up shows on the screen, informing the player that they have just discovered the Pool of Forgetfulness. The cursor also changes, as with any usable object, but if the player decides to press the interaction key, nothing even happens. Perhaps it was a deliberate decision on the part of the developers. Or they just forgot to code it in. That is still, almost twenty years after the release, a subject of discussion. Some might consider it useless, some will consider it a brilliant addition to already clever world and narrative design of this RPG masterpiece.

As Shepard notes in his article, “If video games shared their entire narrative in dialogue and cutscenes, the medium would be little more than a film with interactive portions. Games can do a lot of storytelling in their interactive portions, especially through the environment.” And this is doubly true in the genre of open-world role-playing games, with Morrowind being the perfect representative of such. The developers and writers behind the game were fully aware of that and employed environmental storytelling to its fullest potential. Having it in the game gives the player a possibility to expand their experience, unconstrained by its mechanics or predetermined story. In other words, it is the discrepancy between the actual syuzhet and the story itself that leads to an enriched and enhanced playthroughs. This is also similar to what Jenkins tries to explain when talking about embedded narrative. Citing the author himself: “According to this model, narrative comprehension is an active process by which viewers assemble and make hypothesis about likely narrative developments on the basis of information drawn from textual cues and clues” (Jenkins 9). The only limit is, admittedly, the very imagination of the player.

This non-linear openness of the world has been, surprisingly, a kind of a double-sided axe. Most of the reviews back in 2002 were raving about all the different aspects of the game, but only a few of them gave it the absolute top mark. This very excerpt from an IGN article written by Jason Bates describes it well: “Finally, I'll admit Morrowind isn't for everyone. It's a huge, sprawling, megapolis of a game that can take a couple hours just to get into and a hundred hours to complete. In an industry where most games present clear, linear paths guiding you from one pre-defined problem (a jumping puzzle, a monster, or some other dexterity test) to the next, some gamers will find Morrowind's open-endedness unfamiliar, bewildering, even perplexing. They'll sit there, waiting for someone to come along and tell them what to do.”

This is a very fitting description. With Morrowind, environmental storytelling is not only widely used, it is in a way necessary to provide the player with complete enjoyment and immersion. Some people, when given this unrestricted freedom, will feel lost. The fact that the game is now 17 years old can not be omitted either. Using modern standards, it is quite inaccessible for an average, casual player. The responsibility placed on the player when it comes to experiencing the world the way it is meant to be experienced is now something extra, something that requires additional effort. The later installments, Oblivion and Skyrim, are somewhat more streamlined, bearing more resemblance to this roller-coaster type of entertainment where the player sits back and enjoys the ride. But if the player is willing to overcome this small obstacle, they will be rewarded by a fascinating storytelling experience that is still as magical and mysterious as it has been some 17 years ago.

Works Cited

Bates, Jason. “ELDER SCROLLS III: MORROWIND REVIEW.” IGN.com, https://www.ign.com/articles/2002/06/17/elder-scrolls-iii-morrowind-review?page=3. Accessed 29 March 2019

Bycer,Josh. “How Worldbuilding Elevates Video Games and Fandom.” Gamasutra.com, http://www.gamasutra.com/blogs/JoshBycer/20181107/330000/How_Worldbuilding_Elevates_Video_Games_and_Fandom.php. Accessed 29 March 2019

DrunkDunmer. “TES Morrowind: Tarhiel.”, YouTube, 10 Jan. 2008, www.youtube.com/watch?v=N4N2Gdglde0.

Jenkins, Henry. “Game Design as Narrative Architecture.” Georgia Tech University, http://homes.lmc.gatech.edu/~bogost/courses/spring07/lcc3710/readings/jenkins_game-design.pdf. Accessed 29 January 2019

Stewart, Bart. “Environmental Storytelling.” Gamasutra.com, https://www.gamasutra.com/blogs/BartStewart/20151112/259159/Environmental_Storytelling.php. Accessed 28 March 2019.

1 note

·

View note